1. Introduction

The proliferation of internet technologies and digital platforms has expedited online retail integration into everyday life. Digital platforms, in the form of peer-to-peer technology, serve as infrastructure that enables the convergence of several entities to exchange information, showcase and provide goods and services, conduct transactions, and arrange for the delivery of services [

1]. Digital platform-based marketplaces enable consumers to engage in online retail, providing the convenience of buying from homes [

2,

3,

4]. Consumers can shop without physically visiting commercial areas [

4,

5]. The Platform system is further enhanced by integrating blockchain and geolocation technology, enabling the real-time monitoring of online payment transactions and logistics [

6,

7]. The rising popularity of digital platforms has led to a decline in the frequency of daily trips to city centres [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Those impact demalling in several countries, namely Britain, Belgium, France, Japan, and North America [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Retailers strategically adjust to evolving consumer buying behaviours by relocating their stores closer to residential areas [

16]. This relocation strategy enables them to enhance their desirability due to the reduced delivery cost to consumers [

8,

17].

Following the advent of online retail, it has been observed that restaurants and cafes are now attracting more intra-urban trips than retail shopping [

18,

19,

20,

21]. In response to the burgeoning popularity of this emerging lifestyle, property mall owners have adjusted their offerings by increasing the number of restaurants and cafés available within their commercial properties. Restaurants and cafes play a crucial role in sustaining the vibrancy of malls [

22,

23,

24,

25]. This phenomenon results in a shift in the role of urban commercial centres, transitioning from mostly retail shopping hubs to restaurants and cafes [

26,

27].

As they increasingly supplant retail shopping as crucial components of commercial centres, understanding the features of restaurants and cafés is significant for studying urban economic dynamics amid the rise of online retail. European studies examine how restaurants and cafés populate commercial centres in city and sub-city centres [

16,

20,

26]. The urban south has diverse restaurants, cafes, and formal and informal forms, such as neighbourhood food stalls, roadside stalls, coffee shops at crossroads, and hawkers [

28]. Considering the context of the Urban South's informality, this study aims to reveal the spatial patterns of restaurants, cafés and other such activities after the emergence of online retail. Unlike previous studies that framed their studies on restaurants and cafés [

20,

26], this study applies a broader frame, namely food service.

Food service is the business of serving food and beverages, which are purchased outside the home, but can be consumed outside or inside the home [

29]. A diverse variant of food services can be observed in the urban south. These include fine dining, fast-casual dining, fast food, casual-style dining, cafes, coffee shops, and stalls. Fine dining is characterized by the provision of tailor-made culinary offerings, an ambience that fosters a sense of luxury, and a personalized service experience by the chef [

30]. Fast-casual dining refers to a chain restaurant with a limited menu selection and aims to deliver efficient service through the assistance of waitstaff [

31]. Fast food restaurants are characterized by their specialized menus, typically limited in variety and prepared and served fast [

32]. Casual-style dining offers a selection of speciality cuisine in generous portions [

30]. Café is a type of establishment that provides a refined setting for the consumption of coffee, characterized by a carefully curated interior ambience. A coffee shop is a designated simple place where individuals can consume coffee, typically inside confined seating areas like small booths. A stall is a type of food service establishment, typically a pushcart or a non-permanent tent [

28,

33]. Coffee shop and stall usually grow ribbons on the roadside. Their existence often supports the vitality of urban space. They attract people to trip in urban, but their presence in zones with limited road capacity tends to cause traffic jams and disturb public space [

33]. Given the informal nature of food service in the urban south, this article considers it necessary to understand the spatial pattern of all types of food service amidst the increasing role of food service for intra-city movement after the emergence of online retail. The concept presented in this article is a novel addition to prior research that framed the function of established shopping centres only concerning restaurants and café. This article proposes that after the emergence of online retail, all variants of food services clustered around established shopping centres.

The study was conducted in Surabaya City, the second-largest metropolitan city in Indonesia, with the highest e-commerce penetration rate in Indonesia in 2017 [

34]. The following section discusses data collection methods for various forms of food service and analysis methods to reveal the variety of food service spatial patterns over urban space. The third section discusses the diversity of food service spatial patterns with the previous studies

2. Materials and Methods

The primary objective of this study is to elucidate the spatial distribution of diverse food service activities within Surabaya City. The official documentation contains the restaurants and cafes list, but informal dining is usually undocumented. Nevertheless, by utilizing geotagging technology inside the Google Maps platform, individual business units can add their business detail to ensure visibility to wide consumers. This technology precisely detects the business's location and seamlessly integrates with other service-oriented enterprises on the digital platform. The business unit data on Google Maps is consistently maintained and updated. Such data facilitates the real-time analysis of urban life, introduces novel approaches to urban government, and serves as the foundation for conceptualizing and implementing cities that are more efficient, productive, open, and transparent [

35]. Hence, this study employs the micro-data Point of Interest (POI) of food service units listed on the Google Maps platform. The phases of research implementation are delineated as follows:

2.1. POI Food Service Data Collection

POI food services business units are collected through web scraping on the Google Maps platform. The web scraping process utilizes tools such as the 'Instant Data Scrapper' add-ons compatible with the Google Chrome browser. These tools are employed with the keywords' restoran, cafe, warung kopi.' The data obtained from web scraping is structured in tabular form, comprising several attributes, i.e., location coordinates, name, address, kind, and operational time.

2.2. Clasifying Food Service Types

This step involves classifying food service data into distinct categories: fine dining, fast-casual dining, fast food, casual-style dining, café, coffee shop, and stall variants. The process is approached through four distinct methods. One possible method is categorizing the data based on the information in the 'type attribute' obtained through web scraping. The second method involves filling in the unspecified 'type attribute' by referencing the term attached to the unit name. For instance, the terms' warung, depot, rumah makan' are classified as casual-style dining; and the term 'warkop' is classified as a coffee shop. The third methodology involves the examination of names that explicitly denote franchise restaurant chains. Fast food categories include well-known establishments like McDonald's (McD), Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC), and Pizza Hut (PHD). The fourth possible approach is evaluating the type attribute based on the similarity of criteria. The criteria were formulated under supervised learning by deliberately selecting specific examples. The sample selection is predicated upon the inclusion of renowned individuals that undeniably epitomize a particular category, followed by an analysis of the similarities in attributes within each respective category. The inspection findings suggest that there is a similarity in the operational hours of each variant, as follows:

Fine dining: open at midday (11.00 am or 12.00 pm)

Fast Casual Dining: open at 10.00 am

Fast food: open at 10.00 am

Casual Style Dining: open at 8:00 am or 9:00 am

Café: open on 09.00 am

Coffee shop: open 24 hours

Stall: open half day, morning to noon or afternoon to evening.

Fast-casual dining with fast food and casual-style dining with café have similar operating hours. When discerning between the two options proved challenging for a particular business unit, we employed visual aids such as photos and menus available on the business unit's official website to provide clarification. This clarification technique was exclusively employed for select business units that presented challenges in classification using the preceding four methodologies.

2.3. Typological Analysis of Spatial Patterns

The amalgamation of food service variants determines the classification of urban spatial units. The analysis used the non-hierarchical k-means cluster analysis technique. The K-means clustering technique is utilized to partition data elements into 'k' clusters to maximize the similarity within each cluster while minimizing the similarity between different clusters [

36]. The K-Means method is the most regularly employed and straightforward clustering technique. The K-Means algorithm is frequently employed due to its capacity to cluster substantial datasets, enabling rapid computation efficiently. It facilitates data distribution analysis by initializing centroids and determining the extent of data inside each cluster. This study utilizes the K-means clustering analysis technique in the Jamovi open-source software [

37].

The process of cluster analysis involves several key steps. Firstly, determine the optimal number of clusters. This step involves selecting the appropriate clustering algorithm and evaluating different criteria, using the elbow method to identify the most suitable number of clusters for the given dataset. Once the optimal number of clusters has been determined, the next step is calculating the centroids. Centroids represent the central points of each cluster and are computed based on the attributes or features of the data points within each cluster. This calculation is typically performed using the mean-values formulas. After calculating the centroids, the subsequent step is to describe the characteristics of each cluster. This step involves analyzing the attributes or features of the data points within each cluster and identifying the common patterns or traits that define each cluster. Finally, once the characteristics of each cluster have been identified, it is essential to label the clusters accordingly. Labelling involves assigning labels to each cluster based on their distinguishing characteristics. These labels can provide valuable insights and facilitate the interpretation and understanding of the cluster analysis results. The final phase of the study involves cartographically representing the spatial distribution of each cluster category on the map of Surabaya.

3. Results

3.1. Shopping Retail in Surabaya

Surabaya is the second largest metropolitan city in Indonesia, after the capital city of Jakarta. The urban area originated during the 13th century[

38], serving as a hub for commercial activities and a strategic stronghold in the present-day Tanjung Perak district. The locality saw significant development and transformed into a retail hub featuring modern markets such as Pasar Turi and Pasar Atom, ITC Mega Shopping Mall, and Jembatan Merah Plaza. During the 18th century, Surabaya had significant growth southward, presently referred to as the Tunjungan district [

39]. This expansion established landmarks such as Tunjungan Plaza, Pasar Blauran, BG Junction, and WTC Mall. During the 19th century, the development of Dutch homes in the southern part of what is now known as the Wonokromo district [

39] resulted in the establishment of the Modern Market Wonokromo, Royal Plaza, Marvel City Mall, and Ciputra World. During the 20th century, Surabaya had significant urban expansion towards the western and eastern parts. This expansion was facilitated by constructing the eastern ring road and toll road in the western part of the city [

40]. In 1991, a retail centre emerged in the eastern part of Surabaya, specifically in the Kertajaya district. This retail complex, Galaxy Mall, is conveniently situated close to two campuses, Airlangga University and the Sepuluh November Institute of Technology. The expansion of trade centres persisted, encompassing Plaza Marina and Pakuwon City Mall. In 2005, a new commercial complex emerged in the western part of Surabaya, specifically situated on the border of Dukuh Pakis and Wiyung district. This development included the Pakuwon Mall and Lenmarc Mall. The City of Tomorrow Mall shopping centre has also been established in the Ahmad Yani district, located at the southern end of Surabaya.

Figure 1.

Existing land use and prominent shopping centres in Surabaya.

Figure 1.

Existing land use and prominent shopping centres in Surabaya.

The surge in the prevalence of online retail in Surabaya, as well as other urban areas across Indonesia, has been seen since the year 2015. The proliferation of digital platform applications in e-commerce has significantly expedited the adoption of online retail, mainly through utilizing marketplace dan mobility platforms integrated into smartphones. The phenomenon of platform mobility in Indonesia can be seen as the process of network accumulation [

41]. They initially address mobility needs in areas lacking public transportation by reorganizing informal modes. In urban areas characterized by lenient regulation, digital platforms can diversify their services by venturing into additional sectors [

42,

43], including last-mile delivery services, food ordering, and electronic financing. In 2020 the central government implemented regulations about the pricing standard for online transportation services, measured in rupiah per kilometre.

According to a poll conducted by Google in 2017, Surabaya emerged as the city in Indonesia with the highest number of online retail consumers [

34]. Following the proliferation of online retail platforms, there has been a noticeable decrease in the occupancy rate of shopping centres in Surabaya. Between 2018 and 2019, there was a decline in the occupancy rate, which decreased to 77% and 75%, respectively. During the Covid-19 pandemic, a further fall was observed in the rate, which reached 71.5% [

44,

45]. Conversely, Surabaya's restaurant and café industry experienced notable expansion over the same years. During the fiscal year 2018-2019, the restaurant business unit experienced a growth rate of 20%, while the café segment witnessed a growth range of 15-20% [

44]. This observation suggests that enhancing food services operations in European cities is also occurring in Surabaya.

3.2. Spatial Distribution of Surabaya Food Service

Scrapping was undertaken in January 2022, following a period of 8 years during which the ecosystem platform gained significant popularity in Surabaya. The collected POI data on food services in Surabaya reveals 51,176 units. Seven distinct variants of food services can be defined based on their characteristics. Fine dining restaurants consist of 46 units, fast-casual dining restaurant has 70 units, fast food has 179 units, casual-style dining restaurant has 15,785 units, coffee shops have 3,692 units, and stalls have 25,588 units. The distribution pattern of the location of each food service variant is illustrated in

Figure 2.

The most significant concentration of food services is in two specific areas: Unit 49 Tambak Oso Wilangun, a location for 540 food services, and Unit 123 Tambak Wedi, which accommodates 541 food services. These establishments primarily consist of coffee shops and casual-style dining. Based on the classification of distributions, it is possible to identify two distinct categories. The first sort of dispersion is characterized by its wide distribution throughout the city, encompassing casual-style dining, coffee shops, and stalls. Specific locations exhibit a notable concentration of unit 49 on the boundary of Tambak Oso Wilangun and Sambikerep districts, renowned for its casual-style dining. Unit 93 Wonokromo stands out for its abundance of coffee shops, while Unit 91 Tanjung Perak contains the highest number of stalls. The second category is characterized by a clustering tendency, when businesses typically gather in multiple locations, including fine dining, fast-casual dining, fast food, and café settings. The concentration of high-end dining establishments is observed in nearby areas of Unit 83 Dukuh Pakis and Unit 105 Wonokromo. The concentration of fast food can be observed in three specific locations: Unit 103 Tunjungan, Unit 61 Dukuh Pakis-Wiyung border, and Unit 138 Kertajaya. Cafes are concentrated in the city centre, Unit 103 Tunjungan and Unit 105 Tunjungan-Wonokromo border.

3.3. Food Service's Spatial Pattern Typology

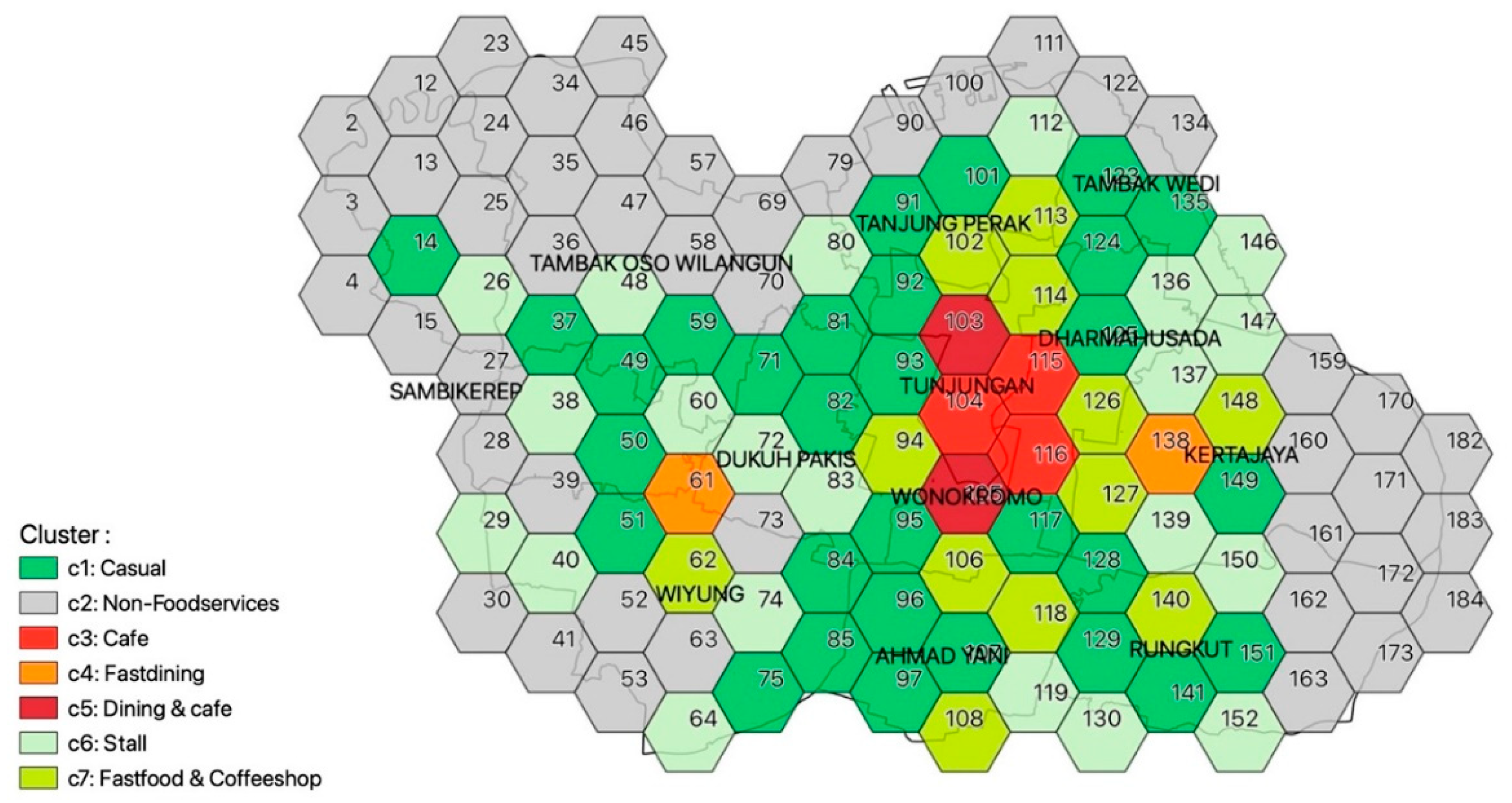

The k-means clustering analysis result, as presented in

Figure 3a, demonstrates seven distinct cluster types.

Figure 3b presents the mean values and demonstrates each cluster's prominent food service variant. Cluster 1 exhibits a comparatively limited quantity of food services compared to the other types of clusters. The predominant variant of food services within this cluster encompasses casual-style dining and coffee shops. Cluster 2 lacks a distinct character due to its comparatively low number of food services compared to other cluster types. Cluster 3 exhibits a higher concentration of cafés compared to the remaining clusters. The prevalence of fast-casual dining within the food service industry primarily characterizes Cluster 4. Cluster 5 exhibits a higher prevalence of fine dining establishments and cafés than the remaining clusters. Cluster 6 has similarities to Cluster 2 in that it lacks a prevailing mean value across all categories of food services. However, the primary food service within this cluster is the stall type. Cluster 7 exhibits a moderate level of food services on average. The highest mean values are observed in the casual-style dining and coffee shops.

Figure 4 shows the categorization of each cluster type based on their distinct characteristics. Cluster 1 is primarily characterized by casual-style dining and coffee shops and is labelled as the Casual Cluster. Cluster 2 is characterized by a lack of food services called the Non-Foodservices Cluster. Cluster 3 is primarily characterized by cafés, collectively forming the Café Cluster. Fast casual dining establishments predominantly characterize Cluster 4, therefore earning the designation of the Fast-Dining Cluster. Cluster 5, the Dining & Café Cluster, is primarily characterized by premium dining and cafes. Cluster 6 is characterized by a limited number of food services, predominantly consisting of stalls, thereby earning the designation of the Stall Cluster. Cluster 7 is primarily characterized by the prevalence of fast food establishments and coffee shops, therefore earning the designation of the Fastfood Cluster.

4. Discussion

The trend of online retail operations through digital platforms has been prevalent for about a decade. Dolega [

20] asserted that the advent of online retail has significantly influenced the decrease in the frequency of shopping trips. Coutinho [

12] highlighted that the decrease in commercial activities within shopping malls led to demalling in several global urban areas. In order to sustain their vibrancy, shopping malls often strive to increase the number of restaurants and cafes they feature.

To date, no empirical evidence indicates a reduction in the frequency of shopping trips within Surabaya. Nevertheless, Surabaya had a decrease in the vibrancy of shopping centres and a simultaneous rise in the presence of café restaurants after the surge in online retail in 2015. Between 2017 and 2019, there was a significant decline of 71.5% in the occupancy rates of retail shopping establishments located within commercial centres. During the same time frame, there was a notable rise of 20% in the number of cafes and restaurants [

44,

45]. In response to the need for resilience in shopping malls, retail stores have relocated from these establishments, subsequently supplanted by the emergence of restaurants and cafes. The case study conducted in the UK reveals that both the city core and sub-centres are predominantly occupied by restaurants and cafes [

20,

26]. In more comprehending the finding, this research elucidates that various categories of café-restaurants do not uniformly aggregate around the existing shopping centre.

This article discloses five distinct urban spaces characterized by varying compositions of food service variants within them. These spaces include the city centre, sub-city centre, areas along main roads, residential neighbourhoods, and peri-urban areas.

City centres typically contain commercial districts known for hosting clusters of high-end dining restaurants and cafes.

Figure 4 displays the units 103-Tunjungan and 105-Wonokromo. The space between the two units is currently utilized by a collection of café clusters, including units 104, 115, and 116. The Tunjungan and Wonokromo districts serve as the city centre. The present locale was established during Dutch colonialism in the 19th century, serving as a leisure hub containing numerous structures of heritage buildings. Fine dining and cafés are typically located close to commercial hubs and hotels [

46,

47], creating an atmosphere of prestige and exclusivity [

48]. This locational pattern resembles the one described by Singleton et al. [

49], wherein the city centre can sustain its vibrancy as a hub for leisure trips due to the distinctive ambience of the old town.

Fast-casual dining clusters characterize sub-city centres. Two shopping malls exhibit this clustering pattern. The first one is located in Unit 61-Wiyung, where Pakuwon Mall is situated. The second one is on Unit 138-Kertajaya, where Galaxy Mall is located. Pakuwon Mall, situated in the western part of the city, is a prominent shopping complex created in a mixed-use format. It is strategically located amidst a lavish residential community, offering a combination of retail spaces and apartments. The Galaxy Mall is situated in the city's eastern part, surrounded by middle-class residential areas and in proximity to two prominent campuses that cater to the younger demographic. Both of these sub-city centres share the characteristic of being situated near residential neighbourhoods.

The area along the main road and surrounding shopping centres tend to be a location for the concentration of fast food restaurants and coffee shops. According to Zhou [

50], fast-food restaurants are often popular places for family leisure activities. It is more advantageous for these establishments to be situated in conveniently accessible places to residential areas [

51], specifically inside the outer tier of the current shopping complex [

50]. The rationale behind selecting this location resembles that observed in Surabaya, where fast-food restaurants are strategically situated along major thoroughfares and close to commercial hubs. However, it can be observed that in the context of Surabaya, indicators suggest a correlation between the number of clusters and the characteristics of the respective neighbourhoods. The number of fast food clusters around the western sub-city centre is comparatively lower than in the eastern centre. The different scales of fast food restaurant clusters around the two sub- city's central areas might indicate the social dynamics prevalent within their surrounding community, as posited by Cachinho [

52] and Thornton [

32]. The lifestyles of the middle class and young individuals exhibit a greater exposure to fast food restaurants than those of higher economic classes.

The casual-style dining and coffee shop clusters are often situated within residential areas. Casual-style dining establishments were primarily characterized by their utilitarian nature [

30]. The dining often accommodated in confined spaces, at the front of the house, garages, and shophouses. The observed pattern aligns with the findings in China, where platform-dependent casual restaurants tend to disperse spatially [

53]. At the same time, peri-urban environments are characterized by the prevalence of food service stalls. Stall clusters are commonly seen between residential land use and undeveloped land use. This situation diverges from the urban north like the UK, wherein the interface space accommodates many restaurants and cafés [

54].

5. Conclusion

Accommodating food services has been recognized as a viable option for mitigating the adverse effects of declining shopping centre activities resulting from the rise of online retail. The provision of food services is a compelling factor that has the potential to draw visitors to urban business hubs. Given the observed dynamics, it is evident that the provision of food services will play a pivotal role in shaping the spatial organization of the urban's retail hierarchy in the following years. This article analyses the spatial distribution of several food service clusters in a southern city with a high concentration and examines these clusters' positioning with the area's existing land uses. The case study Surabaya demonstrates that shopping centres in the city centre exhibit distinct clustering patterns compared to those in the sub-city centres. The research findings indicate a pronounced trend towards a spatial distribution of food services in the city centre, focusing on fine dining restaurants and café. Conversely, the sub-city centre tends to concentrate on fast-casual dining restaurants. Fast food restaurants congregate close to major thoroughfares and in the outer layer of existing shopping centres.

Lastly, this study promotes further investigation about not all extant shopping centres established as sites for food services clusters, suggesting that specific commercial centres may be suitable for developing food services clusters while others may not. Among the previously mentioned establishments, specific retail complexes, namely those located in Tanjung Perak district (unit 102) and Ahmad Yani district (unit 108), do not exhibit the same level of prominence as the two primary commercial centres situated on the western and eastern part of the city. Therefore, it is recommended that additional research be conducted to gain a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing the viability of shopping hubs after the rise of online retailing.

Funding

This research was funded by the Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education/ Lembaga Pengelola Dana Pendidikan (LPDP), grant number 201906211014601.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hein, A.; et al. Digital platform ecosystems. Electronic Markets 2020, 30, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etminani-Ghasrodashti, R.; Hamidi, S. Online shopping as a substitute or complement to in-store shopping trips in Iran? Cities 2020, 103, 102768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, R.; Derudder, B.; Witlox, F. The geography of e-shopping in China: On the role of physical and virtual accessibility. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2022, 64, 102753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, J.; Weekx, S.; Beutels, P.; Verhetsel, A. COVID-19 and retail: The catalyst for e-commerce in Belgium? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2021, 62, 102645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, J.; Cárdenas, I.; Verhetsel, A. Identifying the geography of online shopping adoption in Belgium. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2018, 45, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahviranloo, M.; Baghestani, A. A dynamic crowdshipping model and daily travel behavior. Transp Res E Logist Transp Rev 2019, 128, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasali, R. The Great Shifting, 2018.

- Nahiduzzaman, K.M.; Aldosary, A.S.; Mohammed, I. Framework Analysis of E-Commerce Induced Shift in the Spatial Structure of a City. J Urban Plan Dev 2019, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldo, A.-L.; Andreas, B.; Martin, L. Exploring the associations between E-shopping and the share of shopping trip frequency and travelled time over total daily travel demand. Travel Behav Soc 2023, 31, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørgen, A.; Bjerkan, K.Y.; Hjelkrem, O.A. E-groceries: Sustainable last mile distribution in city planning. Research in Transportation Economics 2021, 87, 100805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerkan, K.Y.; Bjørgen, A.; Hjelkrem, O.A. E-commerce and prevalence of last mile practices. Transportation Research Procedia 2020, 46, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho Guimarães, P.P. Shopping centres in decline: analysis of demalling in Lisbon. Cities 2019, 87, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.J.; Sener, I.N.; Mokhtarian, P.L.; Handy, S.L. Relationships between the online and in-store shopping frequency of Davis, California residents. Transp Res Part A Policy Pract 2017, 100, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallsworth, A.G.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. National high street retail and town centre policy at a cross roads in England and Wales. Cities 2018, 79, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delage, M.; Baudet-Michel, S.; Fol, S.; Buhnik, S.; Commenges, H.; Vallée, J. Retail decline in France's small and medium-sized cities over four decades. Evidences from a multi-level analysis. Cities 2020, 104, 102790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Livingstone, N. The 'online high street' or the high street online? The implications for the urban retail hierarchy. International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 2018, 28, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, I.; Beckers, J.; Vanelslander, T. E-commerce last-mile in Belgium: Developing an external cost delivery index. Research in Transportation Business & Management 2017, 24, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, N.; Urquhart, R.; Newing, A.; Heppenstall, A. Sociodemographic and spatial disaggregation of e-commerce channel use in the grocery market in Great Britain. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2020, 55, 102076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecker, Y.; Strüver, A. Towards alternative platform futures in post-pandemic cities? A case study on platformization and changing socio-spatial relations in on-demand food delivery. Digital Geography and Society 2022, 3, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolega, L.; Reynolds, J.; Singleton, A.; Pavlis, M. Beyond retail: New ways of classifying UK shopping and consumption spaces. Environ Plan B Urban Anal City Sci 2021, 48, 132–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.T.K.; Carrel, A.L.; Shah, H. Impacts of online shopping on travel demand: a systematic review. Transp Rev 2022, 42, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; Tamhane, T.; Vetterrot, B.; Wibowo, P.; Wintels, S. The digital archipelago: How online commerce is driving Indonesia's economic development. Jakarta. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gavilan, D.; Balderas-Cejudo, A.; Fernández-Lores, S.; Martinez-Navarro, G. Innovation in online food delivery: Learnings from COVID-19. Int J Gastron Food Sci 2021, 24, 100330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, R.F.; Ozkan, B.; Mulazimogullari, E. Historical evidence for economic effects of COVID-19. The European Journal of Health Economics 2020, 21, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, L.T.T. Managing the effectiveness of e-commerce platforms in a pandemic. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2021, 58, 102287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C. Reframing the intra-urban retail hierarchy. Cities 2021, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, J.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, S. How has COVID-19 impacted the economic resilience of retail clusters?: Examining the difference between neighborhood-level and district-level retail clusters. Cities 2023, 140, 104457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.C. Foodservice in Singapore: Retaining a place for hawkers? Journal of Foodservice Business Research 2016, 19, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.S.A.; Overstreet, K. What is food service? Journal of Foodservice 2009, 20, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Ok, C. The antecedents and consequence of consumer attitudes toward restaurant brands: A comparative study between casual and fine dining restaurants. Int J Hosp Manag 2013, 32, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Line, N.D.; Hanks, L. A holistic model of the servicescape in fast casual dining. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2020, 32, 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, L.E.; Lamb, K.E.; Ball, K. Fast food restaurant locations according to socioeconomic disadvantage, urban–regional locality, and schools within Victoria, Australia. SSM Popul Health 2016, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recio, R.B.; Gomez, J.E.A. ; Street vendors; their contested spaces, and the policy environment: A view from caloócan, Metro Manila. Environment and Urbanization ASIA 2013, 4, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyani, D.R. Riset Google: Warga Surabaya Paling Banyak Belanja Online. Tempo.co, 15 Aug. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchin, R. The real-time city? Big data and smart urbanism. GeoJournal 2014, 79, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telgarsky, M.; Vattani, A. Hartigan's Method: k-means Clustering without Voronoi. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics; 2010; pp. 820–827. [Google Scholar]

- Kassambra, A.; Mundt, F. factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses. [R package]. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ricklefs, M.C.; Lockhart, B.; Lau, A.; Reyes, P.; Aung-Thwin, M. Sejarah Asia Tenggara Dari Masa Prasejarah Sampai Kontemporer; Depok: Komunitas Bambu, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Handinoto. Arsitektur dan Kota-Kota di Jawa Pada Masa Kolonial; Yogyakarta: Graha Ilmu, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Silas, J. Toll roads and the development of new settlements: The case of Surabaya compared to Jakarta. Bijdr Taal Land Volkenkd 2002, 158, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehlin, J.; Hodson, M.; McMeekin, A. Platform mobilities and the production of urban space: Toward a typology of platformization trajectories. Environ Plan A 2020, 52, 1250–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelzer, P.; Frenken, K.; Boon, W. Institutional entrepreneurship in the platform economy: How Uber tried (and failed) to change the Dutch taxi law. Environ Innov Soc Transit 2019, 33, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuana, S.L.; Sengers, F.; Boon, W.; Raven, R. Framing the sharing economy: A media analysis of ridesharing platforms in Indonesia and the Philippines. J Clean Prod 2019, 212, 1154–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobiz. Tumbuh 20%, Berikut Tren Bisnis Kuliner di Surabaya. gobiz.co.id, 19 Feb. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, D.F. Penyewa Kios Mall di Surabaya Diprediksi Bertambah pada 2022. databoks.katadata.co.id, 25 Jul. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Guan, X.; Huan, T.-C. The spatial agglomeration productivity premium of hotel and catering enterprises. Cities 2021, 112, 103113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, D.L.; Reveiu, A. A spatial analysis of tourism infrastructure in Romania: Spotlight on accommodation and food service companies. Region 2018, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuthahir, S.B.S.; Krishnapillai, G. How does the Ambience of Cafe Affect the Revisit Intention among its Patrons? A S on the Cafes in Ipoh, Perak. In MATEC Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, A.D.; Dolega, L.; Riddlesden, D.; Longley, P.A. Measuring the spatial vulnerability of retail centres to online consumption through a framework of e-resilience. Geoforum 2016, 69, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shen, X.; Wang, C.; Liao, Y.; Li, J. Mining the Spatial Distribution Pattern of the Typical Fast-Food Industry Based on Point-of-Interest Data: The Case Study of Hangzhou, China. ISPRS Int J Geoinf 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widaningrum, D.L.; Surjandari, I.; Sudiana, D. Discovering spatial patterns of fast-food restaurants in Jakarta, Indonesia. Journal of Industrial and Production Engineering 2020, 37, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachinho, H. Consumerscapes and the resilience assessment of urban retail systems. Cities 2014, 36, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talamini, G.; Li, W.; Li, X. From brick-and-mortar to location-less restaurant: The spatial fixing of on-demand food delivery platformization. Cities 2022, 128, 103820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Jiang, Q.; Chen, M.; Liu, L. Quantify the Spatial Association between the Distribution of Catering Business and Urban Spaces in London Using Catering POI Data and Image Segmentation. Atmosphere (Basel) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).