1. Introduction

The FTSC involves network among producers, wholesalers, exporters, and retailers and complex activities. Resilience of FTSC against fluctuation in market variable such as price, cost etc. and climate change shapes the efficiency of supply chain. Sustainability and efficiency of FTSC is highly related with the quality of relationship and income distribution among supply chain actors (1,2). Unfortunately, income distribution among supply chain actors have been unfair up to now. Especially producers have received a smaller share of the profits generated along the supply chain compared to others (3; 4; 5; 6). This inequality leads to a decrease in the producer's net profit and marketing efficiency (7; 8). On the other hand, inefficiencies arise in FTSC cause waste of natural and economic resources, and create food waste (FW) along the supply chains, resulting in negative economic, environmental and social impacts.

The imbalance in income distribution may result in reduced incentives for producers to invest in their farms or improve production processes, ultimately leading to a less sustainable supply chain (9). Recent efforts have been made to address this issue and increase the power of producers, with one such approach involving generating income from recycling waste. Recycling waste can provide an additional source of revenue for actors and enhance their bargaining power. The income disparity among actors in the food supply chain can be addressed by generating income from recycling food loss (FL) and FW.

FL and FW incur a significant economic loss for actors involved in food production and supply chains, particularly for vegetables. FL occur before the food reaches the consumer, while FW is a more complex issue related to retail, the food services sector, and consumers (10). The agricultural food supply chain experiences the highest loss rate in the first link, which is agricultural production. The FL in other nodes is relatively lower comparing to agricultural production. Therefore, the opportunity of generating extra income from FL and FW by recycling of producers is more than that of wholesalers and retailers.

The FL rate for perishable products such as tomatoes is relatively high due to various reasons, including incorrect handling during loading and unloading, poor product storage conditions, unsuitable storage conditions, lack of a clean and sterile environment, insufficient ventilation and cooling systems, lack of pre-cooling after loading, and errors in packaging and sizing of tomatoes (11; 12). And also, the geographical distance between the tomato production and consumption/sales points, as well as the limited accessibility of remote locations, have been incurred as significant for FL and FW (13; 14). For this reason, unbalance income distribution among actors in the tomato supply chain are quite high (5; 3; 6; 4). FL generated along the supply chain by spoilage of fresh products and FW have been important reasons for price fluctuations and income inequality (15; 16; 17; 18; 19; 20; 21; 22; 23; 24; 25; 26; 27; 7; 28).

Up to now, several studies have been conducted to determine the reasons for post-harvest losses of tomatoes, understand the relationships among actors in the supply chain, and explore the scope of reducing FL and increasing profits (29; 5). These studies have revealed that nearly half of the tomatoes produced were spoiled before consumption, and factors such as inadequate raw materials, reliability of logistics networks, technological capabilities, coordination among actors, economic and environmental factors, policies, and market fluctuations affect the performance of the supply chain and lead to losses (30; 31). Therefore, the study focused on the extra income generated by recycling the fresh tomatoes waste to balance the income distribution among the FTSC actors. Tomatoes are among the most widely consumed vegetables globally, with a significant proportion of the global supply chain located in developing countries. Türkiye is the world's third-largest tomato producer, with an annual production of approximately 13 million tons (10) The consumption of tomatoes in Türkiye is primarily in the form of fresh produce or processed goods, such as tomato paste, and dried, or canned products (32). Moreover, Türkiye's tomato exports amount to roughly 519 thousand tons, while approximately 226 thousand tons of tomatoes are processed domestically (33; 34). Türkiye is selected as a research area due to being a good example to reveal the crucial role of income generating from recycling fresh tomatoes waste in reducing inequality in tomato supply chain.

Previous studies have examined FL and FW along the supply chain (30; 35; 36; 37; 38). However, the impact of the economic benefits resulting from recycling on income distribution has yet to be explored. Since the FTSC can become more sustainable, efficient, and equitable via generating income from recycling of FW, this study seeks to explore the potential of recycling FW generated along the FTSC to reduce income inequality and benefit producers. Specifically, this study examines the link between extra income generated from recycling waste and income inequality along the FTSC, with a particular focus on the impact on producer income. The hypothesis of the research is that that recycling tomatoes waste generated along the FTSC can serve as an alternative income source for producers, thereby reducing income inequality and contributing to a more sustainable supply chain. Overall, the aims of the study were to explore the potential of gaining extra income from recycling tomatoes waste generated along the FTSC and to calculate the contribution of extra income from recycling tomato waste to reduce income inequality along the FTSC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Study Area and Data Collection

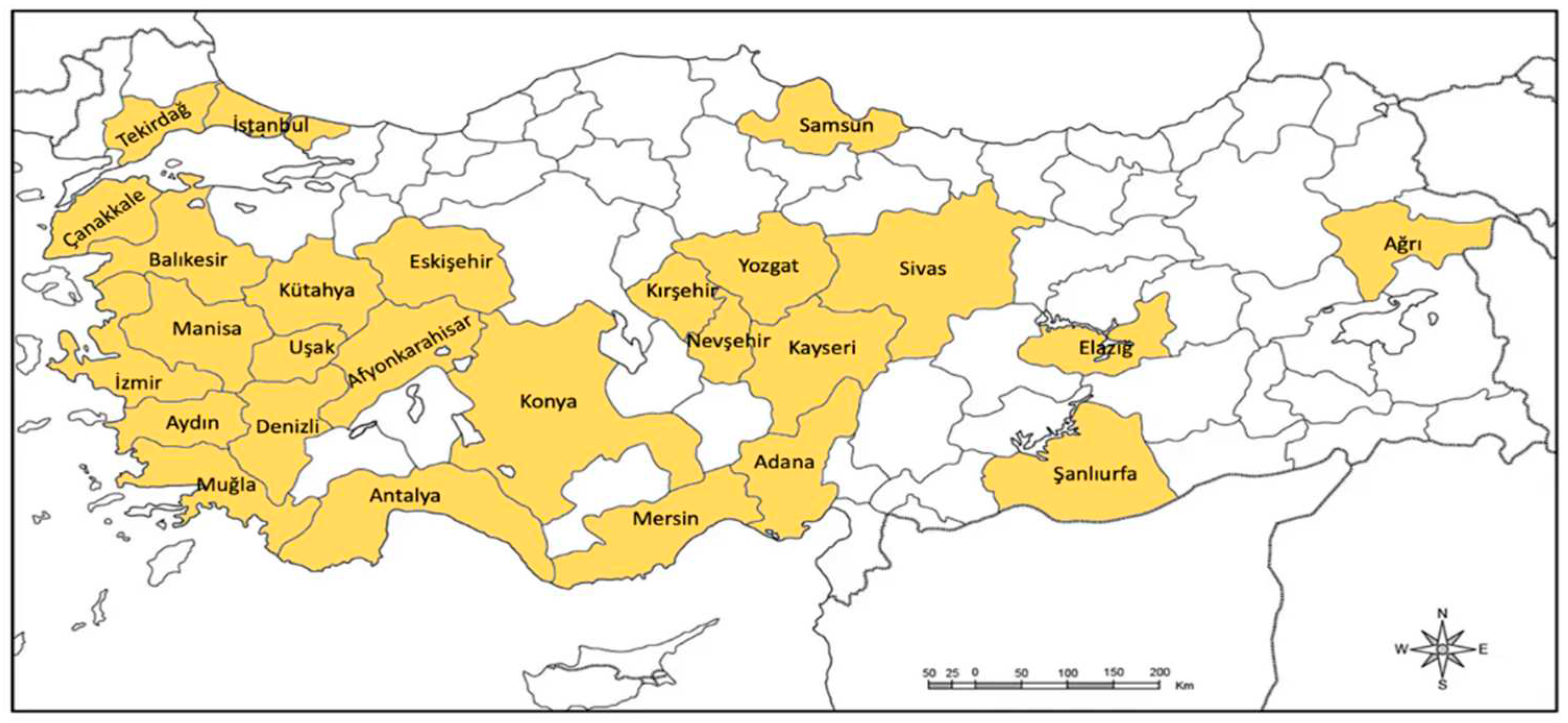

Tomatoes are cultivated both in open field and under greenhouse in Türkiye. The study focused on the greenhouse producers who utilize soilless agriculture technology for cultivating tomatoes, as well as the wholesalers, exporters and retailers involved in Turkish FTSC. Fresh tomatoes cultivated under greenhouse with soilless farming technology in Türkiye are distributed to end-consumers via three distinct supply chains. The boundaries of these supply chains are depicted in

Figure 1.

The first FTSC involves a progression from the producer to the wholesaler, followed by an exporter company and retailer to supply fresh tomatoes to overseas consumers. The second FTSC includes producer, wholesaler and retailer (greengrocer, supermarket, and local market), respectively to reach end-consumer. The third FTSC is shorter one comparing to other supply chains. The travel of fresh tomatoes starts at greenhouse producer, and reaches to consumer through retailer (greengrocer, supermarket, and local market). 60.65% of the Turkish greenhouse producers have been followed the first FTSC, while that of second and third FTSCs were 23.64% and 15.71%, respectively.

The greenhouse tomato production with soilless agriculture technology is located 26 different provinces of Türkiye. The research included the all-active tomatoes producer under greenhouse with soilless production technology in Türkiye. The provinces that have the highest tomato production using soilless agriculture technology are Antalya, which constitutes 22.8% of total Turkish tomato production. The provinces of Afyonkarahisar and Şanlıurfa follow it with the share of 20.6% and 9.6%, respectively (

Figure 2).

The tomatoes produced under greenhouse are supplied to both domestic and overseas market. Consumers living in Antalya, Bursa, and Istanbul have the highest share in domestic tomato consumption. Russia and Ukraine are the top importers of Turkish tomatoes (10).

The producer level research data was collected from 136 producers during the production period of 2021- 2022 using well-structured questionnaires. Questionnaires covered the questions for measuring the variable of production quantity, associated costs (such as those related to fertilizers, pesticides, heating, growing medium, irrigation, electricity, seeds, seedlings, etc.), waste varieties, and amounts.

Due to the difficulties in determining the exact number and characteristics of intermediaries, a snowball sampling method was used to ensure that each link's number of intermediaries equals the number of tomato producers. Snowball sampling has been preferred in previous studies on the tomato supply chain conducted by (39), (40), and (41). Using the snowball sampling method, a total of 220 intermediaries were identified and individuals interviewed across various stages of the tomato supply chain. Selection bias was reduced by tracking the intermediaries (wholesalers, exporters, and retailers) to whom the producers sold their fresh tomatoes. The data was collected via questionnaires from 60 wholesalers, 120 retailers who purchased from wholesalers, 18 exporters, and 22 overseas retailers in examined FTSCs. These data were acquired through individual interviews with each actor included in the tomato supply chain, comprising information on tomato purchasing and selling prices, costs associated with various aspects of the supply chain (storage, labor, transportation, packaging, etc.), as well as the types and quantities of waste produced along the supply chain.

In addition, data obtained from 3 recycling facilities, which are recycled the tomatoes waste generated in examined FTSCs, through semi structured individual interviews were used in the study.

2.2. Eliciting Income Distribution along the Tomato Supply Chain

Production expenses, revenue, net profit per kilogram of fresh tomato produced and sold, and value-added generated along the tomato value chains were calculated for eliciting revenue distribution. Value added was the difference between selling prices of tomatoes at relevant levels of the value chain and it is attributed to absolute marketing margin. The net profit generated in each node of the FTSC was divided by its corresponding revenue when calculating the net profit margin. Net profit was the amount of revenue exceeding the sum of the variable and fixed expenses. Since all calculations in a kilogram basis, tomato price equaled the revenue of intermediaries in each node of the tomato value chains. The variable cost of tomato production included the expenses of fertilizer, heating, growing media, irrigation, electricity, and other expenses. For wholesalers, exporters, and retailers, variable costs were packaging, transport, storing, labor, rent payment, promotion, and general administrative costs. The fixed costs of intermediaries were depreciation, repair-maintenance, rent payment, insurance, interest, and tax.

Share of intermediaries in total net profit and relative marketing margin were also calculated for exploring revenue distribution along the FTSCs. The value added of intermediaries was divided by total value added generated along the tomato value chain to calculate the relative marketing margin. Similarly, the net profit of intermediaries was divided by total net profit of tomato value chains to calculate the share of intermediaries in net profit.

2.3. Exploring the Effect of Revenue from Recycling of Tomato Waste on Income Distribution

Revenue gaining from recycling tomato waste along the tomato supply chain and current income distribution among supply chain actors were used to explore the effect of extra revenue from recycling of tomato waste on income distribution. When calculating the revenue generating from the waste, the amount of waste generating at each node of the tomato supply chains was determined based on the responses of intermediaries at first. At the producer level, tomato waste identified and classified in two different group such as agricultural waste and other waste. Agricultural wastes included waste of plant, product, growing media and drainage. Viol, plastic case, boxes, greenhouse glass, greenhouse plastic cover and rope constituted the other waste. Product waste, pallet waste and box/cardboard waste were the waste generated at the wholesaler, importer and retailer level. Next, the revenue from recycling each type of waste was calculated, based on data from recycling facilities.

Producing compost from organic plant and product waste was used as a recycling method at the producer level based on the findings of (42). (42) stated that composting, producing animal feed, and producing soil conditioners were the alternative recycling methods for organic tomatoes waste and composting organic tomato waste was economically more feasible comparing to other recycling alternatives. Based on data obtained from recycling facilities, the economic revenue of organic plant and product waste per kilogram were USD $ 0.20 and USD $ 0.16, respectively. Compost prices was USD $ 0.2916 per kilogram when calculating the income generating from recycling tomatoes waste in the study. The compost prices in Türkiye was relatively higher comparing to other part of world. Compost prices were USD $0.085 in Indonesia, USD $0.093 in Taiwan, USD $0.25 in Malaysia, USD $0.18 in Sri Lanka and $0.126 in China (43; 44; 45).

In general, growing media wastes can be reused in landscaping work worldwide (46; 47; 48). Similarly, growing media wastes are used for landscape working in Türkiye. Therefore, the economic revenue of reusing growing media wastes in landscaping works was considered by USD $ 0.08 per kilogram in the study. Drainage waste is also one of the important wastes generated in tomato production under greenhouse with soilless agriculture (49). In the study, the revenue generating from recycling drainage waste was used by USD $ 0.36 per kilogram of drainage waste. The revenue obtained from recycling of per kilogram wastes of viol, plastic case, box, pesticide box, greenhouse glass, plastic cover and rope were USD $ 0.24, USD $ 0.37, USD $ 0.26, USD $ 0.26, USD $ 0.14, USD $ 0.47 and USD $ 0.5, respectively, while that of cardboard and pallet wastes were USD $ 0.11 and USD $ 0.14, respectively. The total revenue of tomato wastes was calculated by multiplying the amounts of tomato wastes with corresponding prices.

The difference between current income distribution and income distribution after adding revenue gained from recycling tomatoes waste was attributed to the effect of revenue gained from recycling tomato waste

3. Research Findings and Discussion

Research results showed that greenhouse tomato farms conducted their activities under greenhouse with the size of 5.45 hectares and total tomatoes production of sample greenhouse farms was 2376 tons per year. The production cost of per-kilogram tomatoes was US $ 0.66 and variable expenses constituted 72% of the total unit production cost. The share of fertilizer, heating, growing media, and irrigation and electricity expenses in total variable cost of tomato production were 17%, 21%, 9% and 11%, respectively, while the rest was other expenses. Depreciation cost had the largest share in fixed cost of tomato production by 74%.

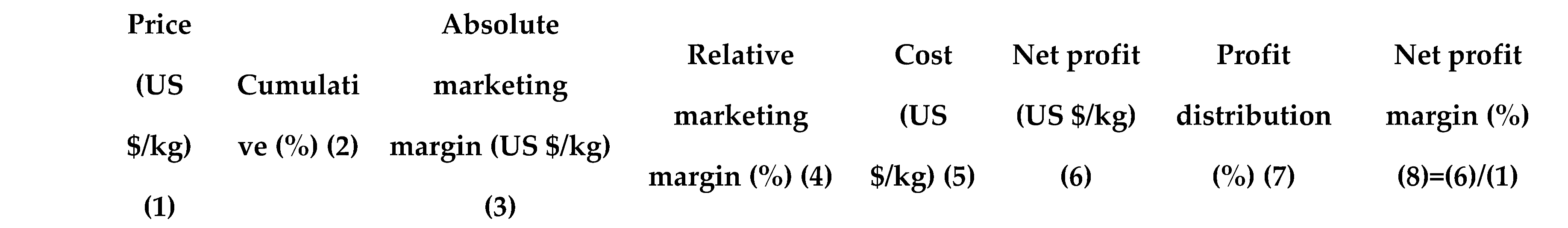

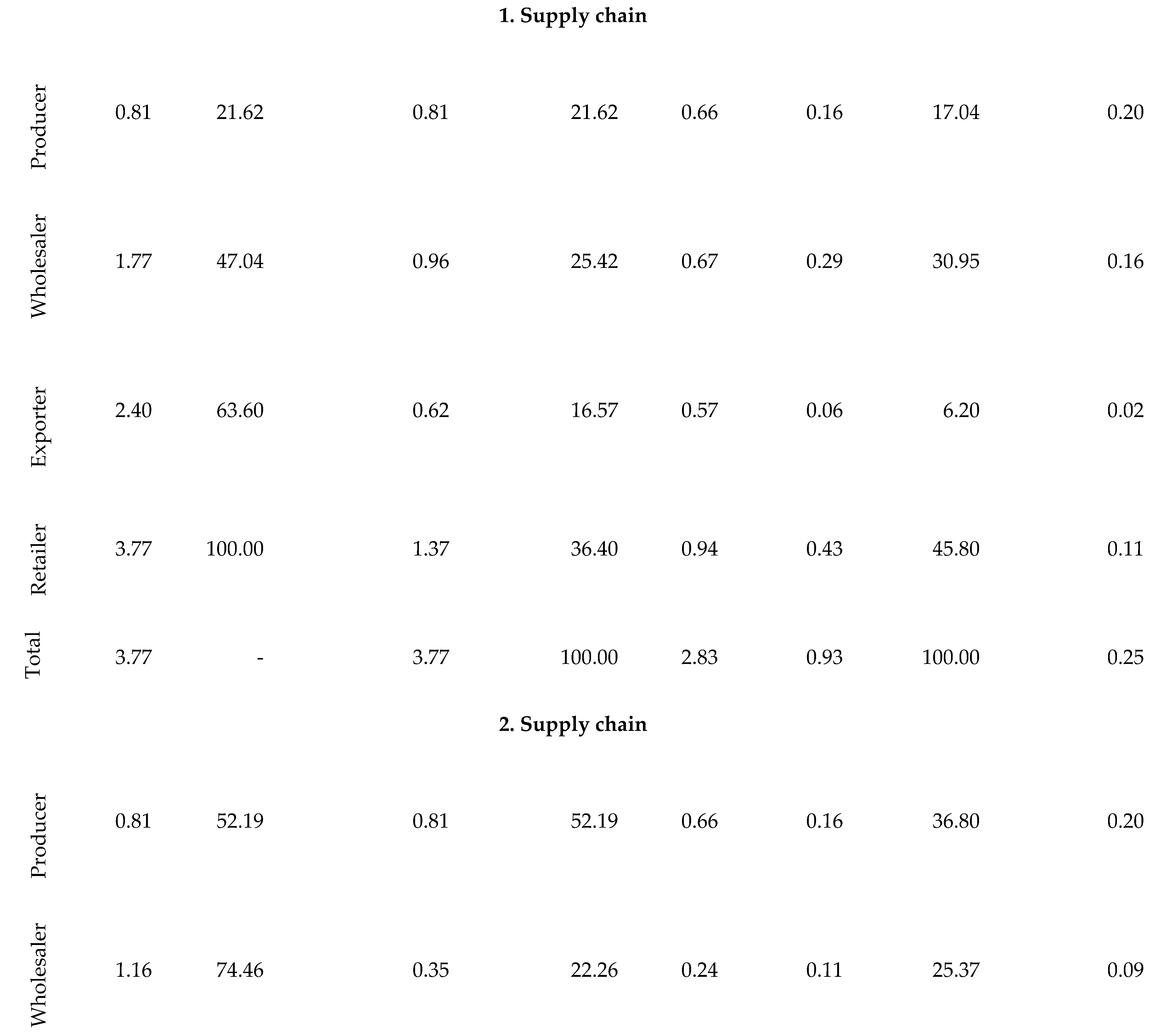

In the first FTSC, the farm gate price of tomato was US $ 0.81/kg and the consumer paid US $ 3.77 for 1 kilogram of tomato. The absolute marketing margin between producer and consumer in the first tomato supply chain was US$ 2.96/kg. The absolute marketing margins between producer and wholesaler and between wholesaler and exporter were US $ 0.96/kg and US $ 0.62/kg, respectively. While it was US$ 1.37/kg between exporter and retailer. The retailer had the highest relative marketing margin among the fresh tomato supply chain actors, while the exporter had the lowest one. 22% of the consumer payment for one kilogram of tomato reached greenhouse tomato producer. Regarding the marketing expenses, it was clear that retailer had the higher marketing expenses along the fresh tomato supply chain. Wholesaler spent US $ 0.67 for transferring one kilogram of tomatoes to exporter. The share of expenses of transport and boxes/cardboard were 18% and 66%, respectively. The cost of transporting one kilogram of tomatoes from exporter to the retailer was US $ 0.50 while that of other cost was US $ 0.07. The total expenses at the retailer level were US $ 0.94 per kilogram and 77% of it was packaging expenses. When glancing at the income distribution among the FTSC actors, it was clear based on the net profit margin (NPM) calculation that retailers had the highest net profit among the FTSC actors. Wholesalers, producers and exporters followed retailers (Table 2).

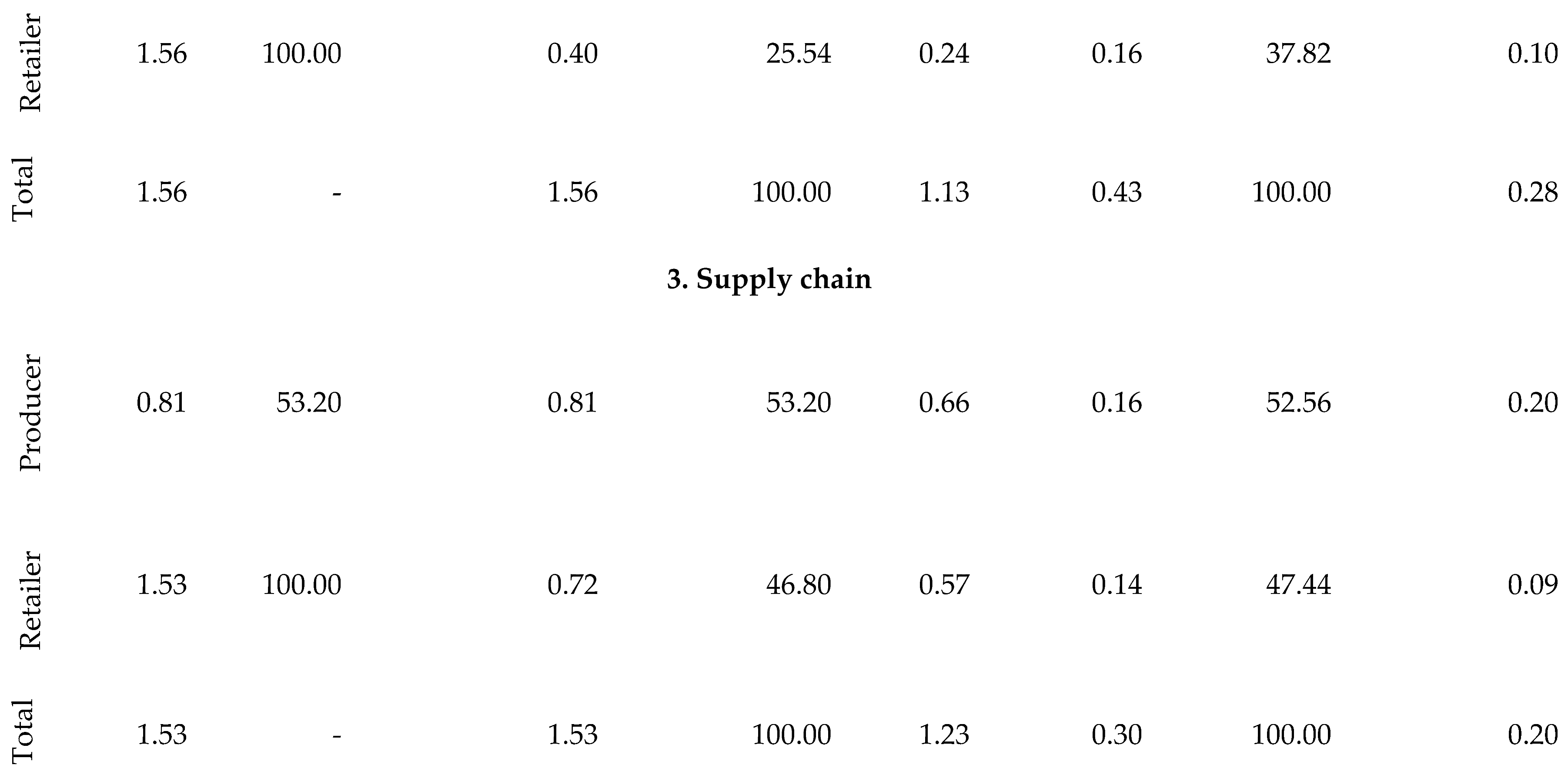

In the second FTSC, the farm gate price of tomato was US $ 0.81/kg and the consumer paid US $ 1.56 for 1 kilogram of tomato. The absolute marketing margin between producer and consumer in the first tomato supply chain was US$ 0.75/kg. The absolute marketing margins between producer and wholesaler and between wholesaler and retailer were US $ 0.35/kg and US $ 0.40/kg, respectively. Producers in second FTSC had the higher marketing expenses along the FTSC. Wholesaler spent US $ 0.24 for transferring one kilogram of tomatoes to exporter. The share of expenses of transport, pallet and boxes/cardboard were 54%, 17% and 13%, respectively. The retailer's expenses differed associated with retailer type. The expenses of greengrocer, supermarket and local market were US $ 0.20, US $ 0.23 and US $ 0.31, respectively. Producers had the highest NPM. Retailers and wholesalers followed producers (Table 2).

In the third FTSC, the absolute marketing margin was US

$ 0.72/kg and the consumer price of tomato is US

$ 1.53/kg. The relative marketing margin of the producer was higher than that of retailers. Retailers in the third FTSC spent US

$ 0.57 for transferring one kilogram of tomatoes to consumers. The share of transport expenses in total unit cost was 91%. The net profit of producers was US

$ 0.16/kg, and that of retailers was US

$ 0.14/kg (

Table 1). Since total net income of FTSC actors is highly depend on both the quantities sold and the net profit of actors in each level of FTSC, considering on quantities of sold by FTSC actors was vital for eliciting accurate income distributions. When considering the quantities sold by actors, it was clear that the first FTSC created a total net income of around 3 million US

$, while that of the second and third ones were 218 and 563 thousand US

$. The rank of producer at first, third, and second FTSC were 4, 3, and 2, respectively. The share of the producer in the total net income of each FTSC increased from the longest FTSC to the shortest one. Producers and wholesalers had more total net income at overseas FTSC than domestic ones. However, the total net income of retailers in the third FTSC was higher than that of overseas ones (

Table 1).

It was clear based on the research results that producer had the highest net profit margin in all FTSCs. This finding confirmed the results of previous studies conducted by (50), (51) and (52). In contrary, some previous studies reported that net profit margin of the producers was the lowest (53; 54). The net profit share of the producer decreased associated with the increasing number of intermediaries. The net profit share of producer exceeded the that of retailers in the third FTSC. This research finding corroborated with the results of (55), (56), (57) and (52).

Greenhouse farms having 5.45 hectares of greenhouse land created 1802 tons of tomato production waste in a year, on average, for 323125.64 tons of total fresh tomato production. Extra revenue generated from composting plant waste, reusing drainage and growing media waste and recycling other waste were US 315 dollars per greenhouse farm and US 57.8 dollars per hectare. Agricultural waste constituted 93.3% of the revenue generated from the tomato wastes, while that of other wastes was 6.7%. The shares of plant waste in the amount of total tomato production waste and extra revenue were 84.37% and 96.23%, respectively. Growing media waste and drainage waste followed the plant waste. Among the other waste types, the most significant contributors to revenue are viol, at 45.7%, and greenhouse glass, at 23.7% (

Table 3).

The amount of waste generated at other stages of the FTSCs and their economic values are depicted in

Table 4. It was inferred based on the research findings that the largest product loss and pallet waste were occurred at the exporter level, and retail level followed it in all FTSCs. However, box and cardboard waste predominantly occurred at the retailer level and exporter and wholesalers followed it. Regarding the revenue gained from recycling the waste, retailer had the highest extra revenue from recycling box/cardboard waste at all FTSCs. Whereas, exporter had the highest extra revenue from recycling product loss and pallet waste (

Table 4).

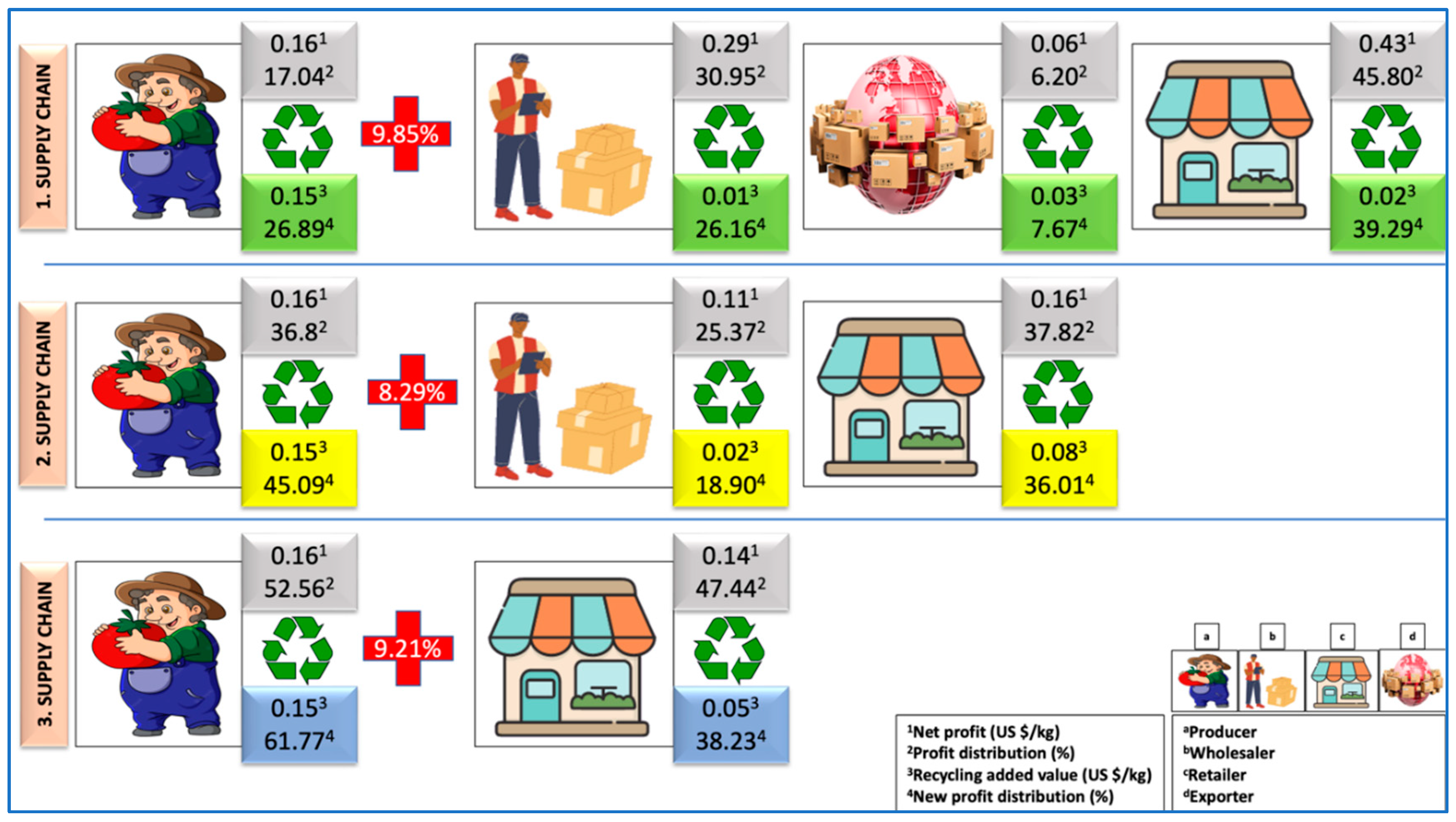

Research results revealed that revenue gained from composting, reusing and recycling of loss and waste increased the welfare of greenhouse producer more than other supply chain actors. Especially at second FTSC, the rank of producer promoted to first place. At first FTSC, the rank of producer raised to above of wholesaler. When taking into account the revenue from composting and recycling of wastes, producers increased their net profit by 9.85% at first FTSC, while that of second and third FTSCs were 8.29% and 9.21%, respectively comparing to the prevailing conditions. The contribution of extra revenue from composting and recycling of wastes to retailers was more comparing wholesaler and exporter. Retailers and wholesalers gaining from recycling in domestic FTSCs was more comparing to overseas one (

Figure 3).

4. Conclusions

This study focused on the revealing contribution of extra income gained from composting and recycling tomato wastes to income distribution of the FTSC actors. The results showed that composting, reusing and recycling of loss and waste increased the welfare of greenhouse producer more than other supply chain actors. In addition, the share of the producer in total net income of each FTSC increased from longest FTSC to shortest one. Research findings also showed that the contribution of the extra income from composting and recycling of wastes in domestic FTSCs was more than that of overseas FTSC. The research results confirmed that composting and recycling tomato wastes serve as an alternative income source for producers, reducing income inequality and contributing to a more sustainable supply chain.

Close cooperation between producers, wholesalers, exporters, retailers, and recycling facilities is essential for the effective implementation of waste recycling initiatives. This collaboration can also lead to the development of innovative solutions and best practices for reducing food loss and waste along the FTSC. Organizing the training and education programs focused on waste management can increase the extra income of producers and active intermediaries in FTSC from composting and recycling tomato wastes. Increasing the efficiency of communication among FTSC actors can also increase the extra revenue from composting and recycling the wastes. And it can smooth the income distributions at the same time. Additionally, offering financial incentives, grants, or subsidies can encourage producers and other actors within the supply chain to adopt waste recycling practices. Facilitating access to appropriate finance sources for investment of composting and recycling tomato wastes can enhance the revenue of each FTSC actors. Continuous research and innovation are crucial in identifying and developing new technologies, processes, and strategies to minimize food loss and waste. Taking these changes will allow the tomato supply chain to achieve more equitable profit sharing while also contributing to a more sustainable and ecologically conscientious future. On the other dimension, dominating fair-trade practices to ensure that all FTSC actors may balance the income distribution among FTSC actors. Regulating competitive market conditions along the FTSC can positively affect the income distribution.

Future research in tomato value chain could extent the scope from fresh tomato to processed tomato when exploring the link between revenue from composting and recycling and income inequality along the FTSC. In addition, the effects of monitoring the supply chains and technology adoption on income distribution among the fresh and processes tomato chain actors could be examined. By considering these factors, stakeholder could benefit deeper understanding of the mechanisms behind inequality in income distribution.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Anastasiadis, F. , Apostolidou, I., & Michailidis, A. (2020). Mapping sustainable tomato supply chain in Greece: A framework for research. Foods, 9(5), 539. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M. , Shah, J. K., & Joshi, S. (2023). Modeling enablers of supply chain decarbonisation to achieve zero carbon emissions: an environment, social and governance (ESG) perspective. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Gautam, S. , Acedo, A.L., Schreinemachers, P. and Subedi, B.P. (2017), “Volume and value of postharvest losses: the case of tomatoes in Nepal”, British Food Journal, Emerald Group Publishing, Vol. 119 No. 12, pp. 2547-2558. [CrossRef]

- Secondi, L. , Principato, L., Ruini, L., & Guidi, M. (2019). Reusing food waste in food manufacturing companies: the case of the tomato-sauce supply Chain. Sustainability, 11(7), 2154. [CrossRef]

- Chaboud, G. , and Moustier, P. (2021). The role of diverse distribution channels in reducing food loss and waste: The case of the Cali tomato supply chain in Colombia. Food Policy, 98, 101881. [CrossRef]

- Mohan, A. , Krishnan, R., Arshinder, K., Vandore, J., & Ramanathan, U. (2023). Management of postharvest losses and wastages in the Indian tomato supply chain—a temperature-controlled storage perspective. Sustainability, 15(2), 1331. [CrossRef]

- Imtiyaz, H. , and Soni, P. (2014). Evaluation of marketing supply chain performance of fresh vegetables in Allahabad district, India. International Journal of Management Sciences and Business Research, 3(1).

- Traub, L.N.; Jayne, T. The effects of price deregulation on maize marketing margins in South Africa. 2008, 33, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, A.A.; Chong, M.; Cordova, M.L.; Camaro, P.J. The impact of logistics on marketing margin in the Philippine agricultural sector. Journal of Economics, Finance and Accounting Studies 2021, 3, 300–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO, (2021). FAOSTAT—FAO database for food and agriculture. FAO FAOSTAT, from Food and agriculture Organisation of United Nations (FAO).

- Tatlıdil, F. F. , Dellal, İ., Bayramoğlu, Z. (2013). Food Losses and Waste in Turkey. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Country Report.

- Karthick, K. , Boris Ajit, A., Subramanaian, V., Anbuudayasankar, S. P., Narassima, M. S., & Hariharan, D. (2023). Maximising profit by waste reduction in postharvest Supply Chain of tomato. British Food Journal, 125(2), 626-644. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. , Underhill, S. and Kumar, S. (2016), “Postharvest physical risk factors along the tomato supply chain: a case study in Fiji”, The Crawford Fund 2016 Annual Conference, Canberra, Australia, pp. 1867-2017, 941. [CrossRef]

- Mashau, M.E. , Moyane, J.N. and Jideani, I.A. (2012), “Assessment of post-harvest losses of fruits at Tshakhuma fruit market in Limpopo Province, South Africa”, African Journal of Agricultural Research, Academic Journals, Vol. 7 No. 29, pp. 4145-4150.

- Anil, K. and Arora, (1999). Post-harvest management of vegetables in Uttar Pradesh hills. Indian Journal of Agricultural Marketing, 13 (2): 6- 14.

- Gupta, S.P. and Rathore, N.S. (1999). Disposal pattern and constraints in vegetable market: A case study of Raipur District of Madhya Pradesh. Agricultural Marketing, 42 (1): 52 – 59.

- More, S. S. (1999). Economics of production and marketing of banana in Maharashtra State. M. Sc. (Agri) thesis, University of Agricultural Science, Dharwad, India.

- Begum, A. and Raha, S. K. (2002). Marketing of Banana in selected areas of Bangladesh. Economic Affairs Kolkata, 47 (3): 158 – 166.

- Sudha, M. , Gajanana, T. M., Murthy, S. D. and Dakshinamoorthy, V. (2002). Marketing practices and post-harvest loss assessment of pineapple in Kerala. Indian Journal of Agricultural Marketing. 16 (1): 56-65.

- Murthy, S. D. , Gajanana, T. M. and Sudha, M. (2002). Marketing practices and post-harvest loss estimated in Mango var. Baganpalli at different stages of marketing – A methodological perspective. Agricultural Economics Research Review. 15 (2): 188-200.

- Singh, S. and Chauhan S. K. (2004). Marketing of Vegetables in Himachal Pradesh. Agricultural Marketing, 5 – 10.

- Bala, B. (2006). Marketing system of apple in hills problems and prospects (A case of Kullu district, Himachal Pradesh), Indian Journal of Agricultural Marketing, 8 (5): 285 -293.

- Murthy, D.S. , Gajanana, T.M., Sudha M. and Dakshinamoorthy (2007). Marketing Losses and their impact on marketing margins: A case study of banana in Karnataka. Agricultural Economics Research Review. 20:47 – 60.

- Adeoye, I.B. , Odeleye, O.M.O., Babalola, S.O. and Afolayan, S.O. (2009). Economic Analysis of Tomato Losses in Ibadan Metropolis, Oyo State, Nigeria. African Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 1, 87-92.

- Rupali, P. and Gyan, P. (2010). Marketable Surplus and marketing efficiency of Vegetables in Indore District: A Micro Level Study. IUP Journal of Agricultural Economics, 7 (3): 84-93.

- Barakade, A. J. , Lokhande, T. N. and Todkari, G. U. (2011). Economics of onion cultivation and its marketing pattern in Satara district of Maharastra.

- Chauhan, C. India Wastes More Farm Food than China: UN. Hindustan Times, 12 September.

- Biswas, A.K.; Tortajada, C. India Must Tackle Food Waste. 2014. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2014/08/ india-perishable-food-waste-population-growth/ (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Ghezavati, V.R. , Hooshyar, S. and Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, R. (2017), “A Benders’ decomposition algorithm for optimizing distribution of perishable products considering postharvest biological behavior in agri-food supply chain: a case study of tomato”, Central European Journal of Operations Research, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Vol. 25 No. 1, pp. 29-54. [CrossRef]

- Handayati, Y. , Simatupang, T.M. and Perdana, T. (2015), “Agri-food supply chain coordination: the state-of-the-art and recent developments”, Logistics Research, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Vol. 8 No. 1, pp. 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Emana, B. , Afari-Sefa, V., Nenguwo, N., Ayana, A., Kebede, D. and Mohammed, H. (2017), “Characterization of pre- and postharvest losses of tomato supply chain in Ethiopia”, Agriculture and Food Security, BioMed Central, Vol. 6 No. 1, pp. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J. Consumer Mark. 2001, 18, 503e520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TURKSTAT. 10 April 2022. Available online: http://www.tuik.gov.tr (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Trade Map. (2023). trademap.org (accessed 10 April 2023). 10 April.

- Underhill, S.J.R. and Kumar, S. (2015), “Quantifying postharvest losses along a commercial tomato supply chain in Fiji: a case study”, Journal of Applied Horticulture, Vol. 17 No. 3, pp. 199-204. [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, T.J. , Singh-Peterson, L. and Underhill, S.J.R. (2017), “Quantifying postharvest loss and the implication of market-based decisions: a case study of two commercial domestic tomato supply chains in Queensland, Australia”, Horticulturae, Vol. 3 No. 3, pp. 21-25. [CrossRef]

- Asrat, F. , Ayalew, A. and Degu, A. (2019), “Turkish journal of agriculture - food science and technology postharvest loss assessment of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) in Fogera”, Vol. 7 No. 8, pp. 1146-1155. [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, I.S. and Semizer, H. (2021), “Effect of good and poor postharvest handling practices on the losses in lettuce and tomato supply chains”, Gida/the Journal of Food, Vol. 46, pp. 859-871.

- Mwagike, L. (2015). The Effect of social networks on performance of fresh tomato supply chain in Kilolo District, Tanzania. International Journal of Business and Economics Research, 4(5), 238-243. [CrossRef]

- Sarma, P. K. (2018). Postharvest losses of tomato: A value chain context of Bangladesh. International Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 4(1), 085-092.

- Maige, L. S. (2022). Analysis on The Factors for Tomato Supply Chain Performance: A Case of Kilosa District.

- Türkten, H. , 2021. Environmental Efficiency of Tomato Growing Farms Having Soilless Culture System and Economic Analysis of Waste Utilization Methods. Samsun.

- Chen, Y.-T. , 2016. A cost analysis of food waste composting in Taiwan. Sustainability 8, 1210. [CrossRef]

- Pandyaswargo, A.H. , Premakumara, D.G.J., 2014. Financial sustainability of modern composting: the economically optimal scale for municipal waste composting plant in developing Asia. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 3, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Zulkepli, N.E. , Muis, Z.A., Mahmood, N.A.N., Hashim, H., Ho, W.S., 2017. Cost benefit analysis of composting and anaerobic digestion in a community: a review. Chem. Eng. Trans. 56, 1777–1782. [CrossRef]

- Montero, J.I. , Antón, M.A., Torrellas, M., Ruijs, M. and Vermeulen, P. 2009. EUPHOROS Deliverable 5. Report on environmental and economic profile of present greenhouse production systems in Europe. European Commission FP7 RDT Project Euphoros (Reducing the need for external inputs in high value protected horticultural and ornamental crops); http://www.euphoros.wur.nl/UK.

- Boldrin, A. , Hartling, K.R., Laugen, M., Christensen, T.H., 2010. Environmental in- ventory modelling of the use of compost and peat in growth media preparation. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 54, 1250e1260. [CrossRef]

- Gruda, N. S. , 2019. Increasing sustainability of growing media constituents and stand-alone substrates in soilless culture systems. Agronomy, 9(6), 298. [CrossRef]

- Mielcarek, A. , Rodziewicz, J., Janczukowicz, W., and Dobrowolski, A., 2019. Analysis of wastewater generated in greenhouse soilless tomato cultivation in central Europe. Water, 11(12), 2538. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, K. R. (2010). Analysis of Tomato Marketing System in Lalitpur District, Nepal. Unpublished Master in Management of Development Specialization International Agriculture. Thesis submitted to Van Hall Larenstein University of Applied Sciences.

- Singh, K. , & Asress, F. C. (2010). Determining working capital solvency level and its effect on profitability in selected Indian manufacturing firms.

- Kaveri Gosavi, D. H. , & Ratnaparkhe, A. N. (2021). Price spread, market margin and marketing efficiency in cauliflower marketing in Maharashtra.

- Pipera, D. , Pagria, I., & Musabelliu, B. Alternatives for improving management of the value chain for greenhouse tomato production in Albania. KONFERENCA E KATËRT, 235.

- Eltahir, M. E. S. , Fadl, K. E. M., Hamad, M. A. A., Safi, A. I. A., Elamin, H. M. A., Abutaba, Y. I. M.,... & Kheiry, M. A. (2023). Tapping Tools for Gum Arabic and Resins Production: A Review Paper. American Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 8(3), 33-40.

- Xaba, B.G.; Masuku, M.B. Factors affecting the productivity and profitability of vegetables production in Swaziland. Journal of Agricultural Studies 2013, 1, 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, A. , & Singh, A. (2016). A hybrid multi-criteria decision making method approach for selecting a sustainable location of healthcare waste disposal facility. Journal of Cleaner Production, 139, 1001-1010. [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, R.; Neupane, N.; Adhikari, D.P. Climatic change and its impact on tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum l.) production in plain area of Nepal. Environmental Challenges 2021, 4, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).