Submitted:

25 August 2023

Posted:

25 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

- age 13–18

- inpatient referral for non-suicidal self-harming behavior, aggressive/impulsive behavior, emotional crises

- voluntary participation in the structured 3 –month DBT-A- in-patient program

- diagnoses of schizophrenic or affective psychosis

2.2. Sample description

| Sample description | |

|---|---|

| Participants (n) | n = 138 |

| gender % (n) male female |

12,3 (17) 87,7 (121) |

|

M (±SD) Age (min. – max.) |

16,5 (1,3) 13,7 – 18,8 |

|

M (±SD) (Duration of treatment in weeks) |

14,9 (5,9) |

2.3. Diagnoses

2.4. Statistical analyses

2.5. Experimental Intervention and Instruments

Experimental Intervention

2.6. Psychometric Assessments:

Assessment of Identity Development in Adolescence (AIDA)

Reliability:

Validity:

Depression inventory for children and adolescents (DIKJ) [35]

Symptom Checklist (SCL-90-R) [36]

Questionnaire for the Assessment of Emotional Regulation in Children and Adolescents (FEEL-KJ) [37]

Scales for Experiencing Emotions (SEE) [39]

3. Results

Comparison “completer versus non-completer”

| completer n= 138 |

non completer n = 50 |

MANOVA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (±SD) | Mean (±SD) | F(df) | Sig. | partial η2 | |

| Diffusion (AIDA) | 65,79 (13,130) | 60,92 (14,351) | 4,80 (1) | .030 | .025 |

| Depression (DIKJ) | 64,18 (11,68) | 57,78 (13,939) | 9,82 (1) | .002 | .050 |

| GSI (SCL-90-R) | 67,82 (11,706) | 62,88 (12,589) | 6,27 (1) | .013 | .033 |

| FEEL-KJ - adaptive strategies (total) | 37,29 (12,793) | 40,76 (11,701) | 2,82 (1) | .095 | .015 |

| FEEL-KJ - maladaptive strategies (total) | 62,19 (13,422) | 58,80 (14,054) | 2,28(1) | .133 | .012 |

Assessment of Impairment of Identity Development in Adolescence (AIDA)

Depression Inventory for Children and Adolescents (DIKJ)

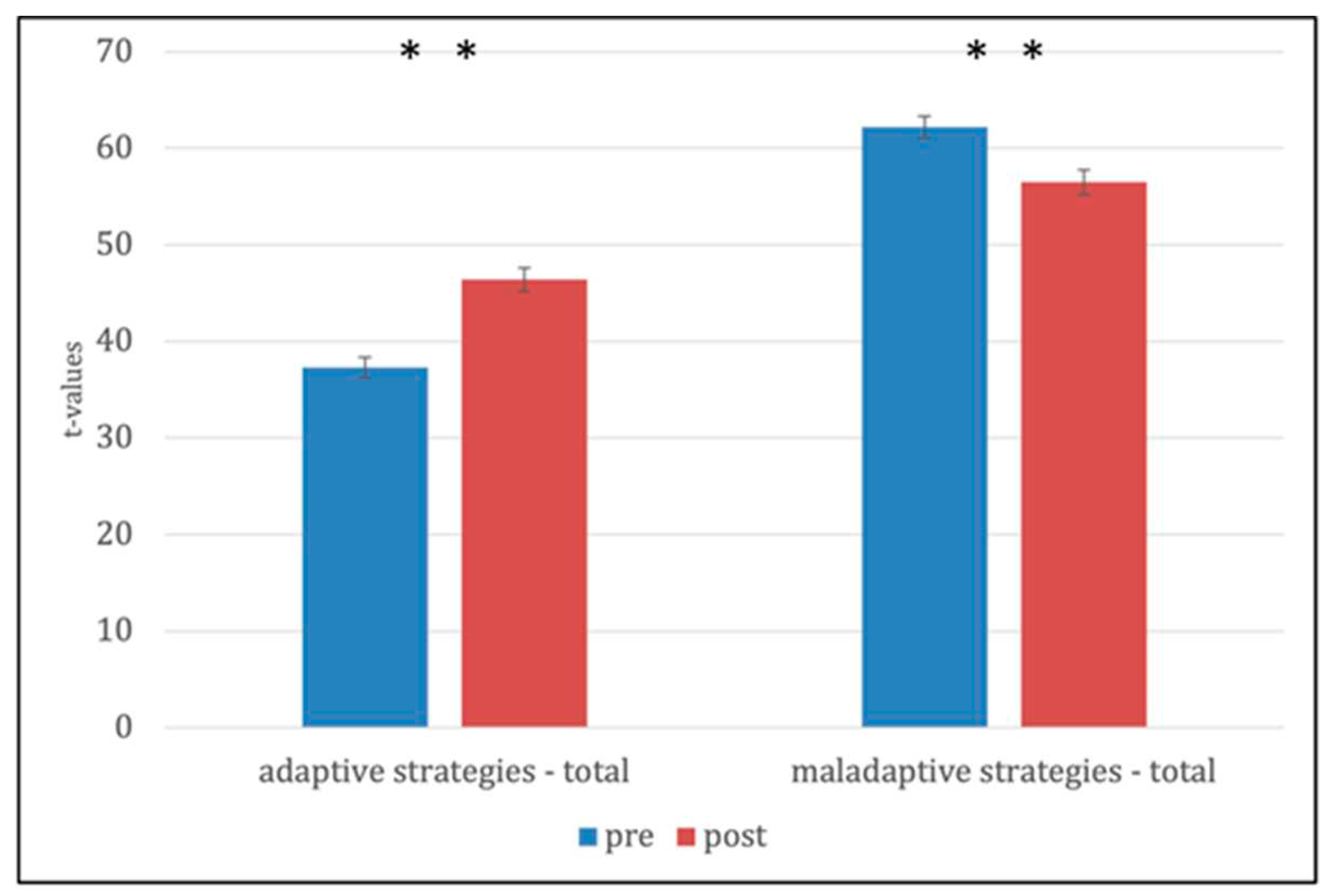

Questionnaire for the Assessment of Emotional Regulation in Children and Adolescents (FEEL-KJ) [37]

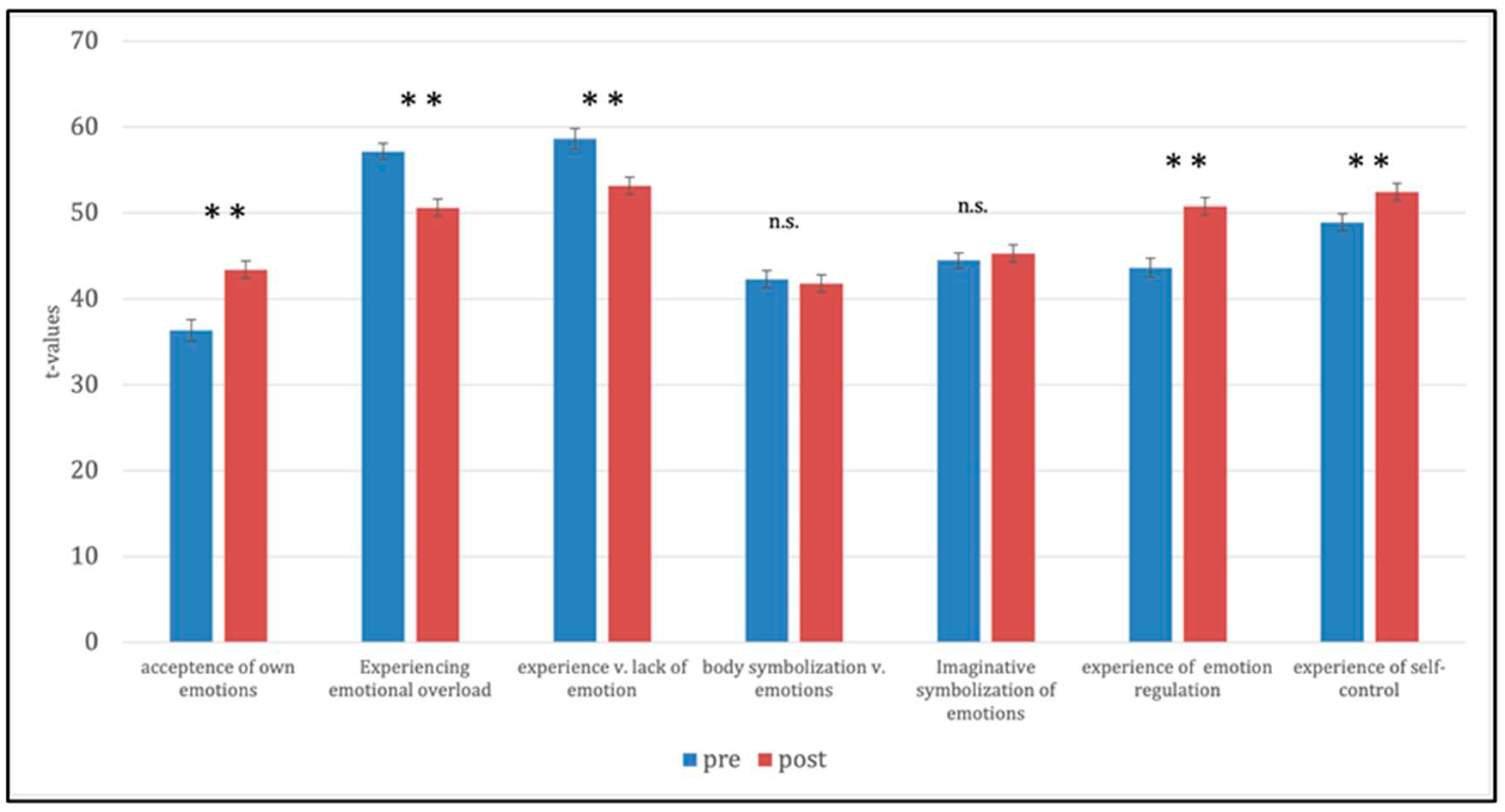

Scales of Experience Emotions (SEE) [39]

4. Discussion

Limitations:

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics Statement

Abbreviations

References

- Linehan, M.M. Naturalistic Follow-up of a Behavioral Treatment for Chronically Parasuicidal Borderline Patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993, 50, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linehan, M.M. Behavioral Treatments of Suicidal Behaviors: Definitional Obfuscation and Treatment Outcomes; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (UK), 1997.

- Linehan, M.M. DBT Skills Training Manual: Second Edition 2014.

- Copeland, W.E.; Shanahan, L.; Egger, H.; Angold, A.; Psych, M.R.C.; Costello, E.J. Adult Diagnostic and Functional Outcomes of DSM-5 Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2014, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, A.L. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation. Dev Psychopathol 2019, 31, 1143–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, M.; Dykstra, E.J. Dialectical Behaviour Therapy for Special Populations: Treatment with Adolescents and Their Caregivers. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities 2011, 5, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, C.; Wall, K. Personality Pathology Grows up: Adolescence as a Sensitive Period. Current Opinion in Psychology 2018, 21, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.L.; Wyman, S.E.; Huppert, J.D.; Glassman, S.L.; Rathus, J.H. Analysis of Behavioral Skills Utilized by Suicidal Adolescents Receiving Dialectical Behavior Therapy. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 2000, 7, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.L.; Rathus, J.H.; Linehan, M.M. Dialectical Behavior Therapy with Suicidal Adolescents; Guilford Press, 2006; ISBN 978-1-60623-789-2.

- Rathus, J.; Campbell, B.; Miller, A.; Smith, H. Treatment Acceptability Study of Walking The Middle Path, a New DBT Skills Module for Adolescents and Their Families. APT 2015, 69, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischhaker, C.; Böhme, R.; Sixt, B.; Brück, C.; Schneider, C.; Schulz, E. Dialectical Behavioral Therapy for Adolescents (DBT-A): A Clinical Trial for Patients with Suicidal and Self-Injurious Behavior and Borderline Symptoms with a One-Year Follow-Up. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2011, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, C.; Fonagy, P. Practitioner Review: Borderline Personality Disorder in Adolescence – Recent Conceptualization, Intervention, and Implications for Clinical Practice. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2015, 56, 1266–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaess, M.; Brunner, R.; Chanen, A. Borderline Personality Disorder in Adolescence. PEDIATRICS 2014, 134, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanen, A.; Sharp, C.; Hoffman, P. Prevention and Early Intervention for Borderline Personality Disorder: A Novel Public Health Priority. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 215–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Auer, A.K.; Bohus, M. Interaktives Skillstraining für Jugendliche mit Problemen der Gefühlsregulation (DBT-A): Das Therapeutenmanual - Akkreditiert vom Deutschen Dachverband DBT; Klett-Cotta, 2018; ISBN 978-3-608-26934-5.

- Rathus, J.; Miller, A.; Paul, H. Rathus, J.H.; Miller, A.L.; Paul, H. DBT Skills Manual for Adolescents. Guilford Press Child & Family Behavior Therapy 2015, 37, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buerger, A.; Fischer-Waldschmidt, G.; Hammerle, F.; von Auer, K.; Parzer, P.; Kaess, M. Differential Change of Borderline Personality Disorder Traits During Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Adolescents. Journal of Personality Disorders 2019, 33, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, L.R.; Kaplan, C.; Aguirre, B.; Galen, G.; Stewart, J.G.; Tarlow, N.; Auerbach, R.P. Treatment Effects Following Residential Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Adolescents with Borderline Personality Disorder. Evid Based Pract Child Adolesc Ment Health 2018, 3, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sollberger, D.; Gremaud-Heitz, D.; Riemenschneider, A.; Küchenhoff, J.; Dammann, G.; Walter, M. Associations between Identity Diffusion, Axis II Disorder, and Psychopathology in Inpatients with Borderline Personality Disorder. Psychopathology 2012, 45, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmeck, K.; Schlüter-Müller, S. Early Detection and Intervention for Borderline Personality Disorder in Adolescence. Socijalna psihijatrija 2017, 45, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M.; Schmeck, K.; Petermann, F. Persönlichkeitsstörungen im Kindes- und Jugendalter? Kindheit und Entwicklung 2008, 17, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevecke, K.; Lehmkuhl, G.; Petermann, F.; Krischer, M.K. Persönlichkeitsstörungen Im Jugendalter. Kindheit und Entwicklung 2011, 20, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernberg, P.F.; Weiner, A.S.; Bardenstein, K.K. Persönlichkeitsstörungen bei Kindern und Jugendlichen; Klett-Cotta, 2001; ISBN 978-3-608-94323-8.

- Foelsch, P. The Essentials of Identity – Differentiating Normal from Pathological. Neuropsychiatrie de l’Enfance et de l’Adolescence 2012, 60, S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, F.; Gambin, M.; Sharp, C. Childhood Maltreatment and Identity Diffusion among Inpatient Adolescents: The Role of Reflective Function. Journal of Adolescence 2019, 76, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevecke, K.; Schmeck, K.; Krischer, M. Das dimensional-kategoriale Hybridmodell für Persönlichkeits- störungen im DSM-5 aus jugendpsychiatrischer Perspektive: Kritik und klinischer Ausblick. Zeitschrift für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie und Psychotherapie 2014, 42, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmeck, K.; Schlüter-Müller, S.; Foelsch, P.A.; Doering, S. The Role of Identity in the DSM-5 Classification of Personality Disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2013, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erikson, E.H. Identity: Youth and Crisis; Reissued as Norton paperback 1994.; W. W. Norton & Company: New York London, 1994; ISBN 978-0-393-31144-0. [Google Scholar]

- Foelsch, P.A.; Schlüter-Müller, S.; Odom, A.E.; Arena, H.T.; Borzutzky, H.A.; Schmeck, K. Adolescent Identity Treatment; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2014; ISBN 978-3-319-06867-1. [Google Scholar]

- Gander, M.; Buchheim, A.; Bock, A.; Steppan, M.; Sevecke, K.; Goth, K. Unresolved Attachment Mediates the Relationship Between Childhood Trauma and Impaired Personality Functioning in Adolescence. Journal of Personality Disorders 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goth, K.; Foelsch, P.; Schlüter-Müller, S.; Birkhölzer, M.; Jung, E.; Pick, O.; Schmeck, K. Assessment of Identity Development and Identity Diffusion in Adolescence - Theoretical Basis and Psychometric Properties of the Self-Report Questionnaire AIDA. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2012, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goth, K.; Birkhölzer, M.; Schmeck, K. Assessment of Personality Functioning in Adolescents With the LoPF–Q 12–18 Self-Report Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment 2018, 100, 680–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, F.W.; Ohmann, S.; Möhler, E.; Plener, P.; Popow, C. Emotional Dysregulation in Children and Adolescents With Psychiatric Disorders. A Narrative Review. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 628252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euler, S.; Dammann, G.; Endtner, K.; Leihener, F.; Perroud, N.A.; Reisch, T.; Schmeck, K.; Sollberger, D.; Walter, M.; Kramer, U. Borderline-Störung: Behandlungsempfehlungen Der SGPP. Swiss Archives of Neurology, Psychiatry and Psychotherapy 2018, 169, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joachim Stiensmeier-Pelster; Monika Braune-Krickau, Karin Duda, Ed.; Martin Schürmann; Karin Duda Depressionsinventar Für Kinder Und Jugendliche; Hogrefe: Göttingen, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, G. Die Symptom-Checkliste von Derogatis (SCL-90-R) - Deutsche Version - Manual; Hogrefe: Göttingen, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Grob, A.; Smolenski, C. Fragebogen Zur Erhebung Der Emotionsregulation Bei Kindern Und Jugendlichen (FEEL-KJ); 2nd ed.; Huber: Bern, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, M.; Becker, M. Skalen Zum Erleben von Emotionen; Hogrefe: Göttingen, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, R.; Fürer, L.; Schenk, N.; Koenig, J.; Roth, V.; Schlüter-Müller, S.; Kaess, M.; Schmeck, K. Silence in the Psychotherapy of Adolescents with Borderline Personality Pathology. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.; Pick, O.; Schlüter-Müller, S.; Schmeck, K.; Goth, K. Identity Development in Adolescents with Mental Problems. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2013, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K.N.; Jackson, H.; Cavelti, M.; Betts, J.; McCutcheon, L.; Jovev, M.; Chanen, A.M. The Clinical Significance of Subthreshold Borderline Personality Disorder Features in Outpatient Youth. Journal of Personality Disorders 2019, 33, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; Thompson, R.A. Emotion Regulation: Conceptual Foundations. In Handbook of emotion regulation; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, US, 2007; pp. 3–24. ISBN 978-1-59385-148-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fergus, S.; Zimmerman, M.A. ADOLESCENT RESILIENCE: A Framework for Understanding Healthy Development in the Face of Risk. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2005, 26, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Auer, A.K.; Bohus, M. Interaktives Skillstraining für Jugendliche mit Problemen der Gefühlsregulation (DBT-A): Das Therapeutenmanual - Akkreditiert vom Deutschen... - Inklusive Keycard zur Programmfreischaltung; 1.; Schattauer, 2017; ISBN 978-3-608-43116-2.

- Schrobildgen, C.; Goth, K.; Weissensteiner, R.; Lazari, O.; Schmeck, K. Der OPD-KJ2-SF – Ein Instrument zur Erfassung der Achse Struktur der OPD-KJ-2 bei Jugendlichen im Selbsturteil. Zeitschrift für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie und Psychotherapie 2019, 47, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birkhölzer, M.; Goth, K.; Schrobildgen, C.; Schmeck, K.; Schlüter-Müller, S. Grundlagen Und Praktische Anwendung Des Assessments of Identity Development in Adolescence (AIDA)/ Background and Practical Use of the Assessment of Identity Development in Adolescence (AIDA). Praxis der Kinderpsychologie und Kinderpsychiatrie 2015, 64, 584–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixius, A.; Möhler, E. Feasibility and Effectiveness of a New Short-Term Psychotherapy Concept for Adolescents With Emotional Dysregulation. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 585250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixius, A.; Michael, T.; Altpeter, A.; Ramos Garcia, R.; Möhler, E. Adolescents in Acute Mental Health Crisis : Pilot-Evaluation of a Low-Threshold Program for Emotional Stabilization. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Dixius, A.; Möhler, E. START – Entwicklung einer Intervention zur Erststabilisierung und Arousal-Modulation für stark belastete minderjährige Flüchtlinge. Praxis der Kinderpsychologie und Kinderpsychiatrie 2017, 66, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixius, A.; Möhler, E. A Pilot Evaluation Study of an Intercultural Treatment Program for Stabilization and Arousal Modulation for Intensely Stressed Children and Adolescents and Minor Refugees, Called START (Stress-Traumasymptoms-Arousal-Regulation-Treatment). ARC Journal of Psychiatry 2017.

| Diagnosen | ICD-10 | Frequency(n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjustment disorder | F43.2 | 4 | 3 |

| Anorexia nervosa | F50.1 | 25 | 18 |

| Bulimia nervosa | F50.2 | 7 | 5 |

| Dissociative convulsions | F44.5 | 1 | 1 |

| Emotionally unstable personality disorder | F60.31 | 47 | 34 |

| Moderate depressive episode | F32.1 | 15 | 11 |

| Other mixed disorders of conduct and emotions | F92.8 | 1 | 1 |

| Other specific personality disorders | F60.8 | 1 | 1 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | F43.1 | 34 | 24 |

| Social phobia | F40.1 | 2 | 1 |

| Somatization disorder | F45.0 | 1 | 1 |

| Assessment of Identity Development in Adolescence (AIDA) Depression Inventory for Children and Adolescents (DIKJ) Symptom Checklist- (SCL-90-R: Global Severity Index) | |||||||

| AIDA | M T1 (±SD) | M T2 (±SD) | M dif (±SD) | t | df | p | d |

| Diffusion | 65.8 (13.1) | 58.7 (15.9) | 7.1 (-2.8) | 5.579 | 137 | < .001 | .67 |

| Discontinuity | 67.2 (12.9) | 60.9 (15.5) | 6.3 (10.3) | 5.104 | 137 | < .001 | .63 |

| Incoherence | 63.2 (13.4) | 57.2 (15.3) | 6,0 (-1.9) | 4.997 | 137 | < .001 | .68 |

| DIKJ | 67.8 (11.7) | 59.7 (14.6) | 8.1 (-2.9) | 7,085 | 137 | < .001 | 0.91 |

| GSI (SCL-90-R) | 64.2 (11.8) | 55.5 (14.6) | 8.7 (-2.8) | 7,282 | 137 | < .001 | 0,83 |

| FEEL-KJ | M T1 (±SD) | M T2 (±SD) | M dif. (±SD) | t | df | p | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| adaptive strategies (total) | 37.3 (12.8) | 46.4 (14.5) | -9.1 (-1.7) | -7.256 | 137 | < .001 | -1.02 |

| Anger | 38.1 (12.1) | 46.7 (13.5) | -8.6 (-1.4) | -7.050 | 137 | < .001 | -1.03 |

| Anxiety | 38.2 (12.4) | 46.9 (14.1) | -8.7 (-1.7) | -6.135 | 137 | < .001 | -.80 |

| Grief | 38.9 (12.3) | 46.6 (13.8) | -7.7 (-1.5) | -6.249 | 137 | < .001 | -.86 |

| maladaptive strategies (total) | 62.2 (13.4) | 56.5 (15.3) | 5.7 (-1.9) | 4.809 | 137 | < .001 | .48 |

| Anger | 59.9 (13.0) | 55.3 (14.2) | 4.6 (-1.2) | 4.176 | 137 | < .001 | .49 |

| Anxiety | 60.5 (13.7) | 55.8 (15.3) | 4.7 (-1.6) | 3.644 | 137 | < .001 | .37 |

| Grief | 61.4 (12.2) | 55.6 (13.7) | 5.8 (-1.5) | 5.354 | 137 | < .001 | .62 |

| SEE | M T1(±SD) | M T2(±SD) | M dif(±SD) | t | df | p | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| acceptance of own emotions | 36.1. (14.8) | 43.4 (17.2) | -7.3 (-2.4) | -4,917 | 137 | < .001 | -.66 |

| experience of emotion regulation | 57.3 (11.2) | 50.6 (12.4) | 6.7 (-1.2) | 5,619 | 137 | < .001 | .82 |

| experience of emotional overload | 58.9 (14.1) | 53.2 (13.3) | 5.7 (1.0) | 4,419 | 137 | < .001 | .48 |

| body symbolization of emotions | 42.2 (11.8) | 41.8 (11.8) | 0.4 (0,0) | 0.409 | 137 | > .05 | - |

| imaginative symbolization of emotions | 44.5 (10.4) | 45.3 (10.4) | -0.8 (0.0) | -1.017 | 137 | > .05 | - |

| experience v. Emotion regulation | 43.3 (12.7) | 50.8 (13.4) | -7.5 (-0.7) | -5.458 | 137 | < .001 | -.79 |

| experience v. self-control | 48.7 (11.6) | 52.5 (11.3) | -3.8 (0.3) | -3.884 | 137 | < .001 | -.46 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).