1. Introduction

Stabilization of organic matter is one of the main factors ensuring the ecological functions of soil, and is the most important component of the global carbon cycle. One of the reasons for increasing the resistance of soil organic matter (SOM) to chemical oxidation and microbial degradation is its fixation on the mineral soil matrix [

1,

2]. The main mechanisms of SOM sorption on minerals include ligand exchange, formation of bridge bonds through polyvalent cations, hydrophobic and van der Waals interactions. These mechanisms occur in soil simultaneously, and predominance of one or another mechanism is determined by the properties of sorbent minerals, soil solution (pH, ionic strength) and organic matter dissolved in it [

3,

4,

5,

6].

SOM sorption on clay minerals increases with decreasing pH and increasing ionic strength [

4,

7,

8,

9], as well as in presence of iron cations [

9,

10], aluminum [

11], calcium [

12,

13], and copper [

14].

Numerous studies show that interaction of organic matter (OM) with the mineral soil matrix leads to increased thermal stability of organic matter [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Thermal analysis allows us to estimate the energy barrier of OM destruction or the stored energy released during microbiological destruction of OM [

22,

23,

24]. Barré et al. established that burning more thermally stable soil organic matter releases less energy than burning thermolabile OM, and soil microorganisms prefer to oxidize high-energy OM, leaving material with a low energy store [

17]. Peltre et al. revealed a negative relationship between the resistance of organic matter sorbed on the surface of minerals to microbial action and its thermal stability [

24].

However, the relationship between resistance to microbial degradation and thermal stability is not always absolute [

22,

23,

24,

25]. Zhang et al. showed that low molecular weight SOM fractions can be strongly retained in micropores [

10]. In this case, it becomes more difficult for microbes to decompose organic matter and its resistance to microbial decomposition increases significantly [

3,

16,

26], while thermal stability remains unchanged. In addition, the literature provides the results of sorption experiments with sorbates and sorbents of different compositions and under different sorption conditions, which makes it difficult to compare and outline general sorption regularities, thermal stability, and resistance to microbial oxidation of the sorbed organic matter.

In nature, organic matter sorption occurs both on the surfaces of minerals and on new sorption centers made by the sorbed organic matter. Considering the zonal model of organomineral interactions [

16], the sorbed organic matter at different distances from the surface is likely to have different thermal characteristics, different chemical composition, and different resistance to microbial oxidation.

The purpose of this study was to assess resistance to thermal effects and microbial oxidation of humic acid fixed on the surface of kaolinite, muscovite and bentonite during three sorption cycles.

2. Materials and Methods

Sorbents. Sorption experiments were carried out using bentonite clay, kaolinite, and muscovite. Bentonite clay was selected from the Sarigyuh deposit (the Republic of Armenia). A detailed description of bentonite is given in the work by Chechetko et al [

27]. Kaolinite was produced at the Prosyanovsk deposit (Ukraine). Muscovite was produced by JSC “GEOKOM” and is sold under the commercial name “FRAMIKA”.

Sorbate. A commercial product of potassiumhumate (“POWHUMUS” (Humintech GmbH, Dusseldorf Hansaalee 201, D-89079) isolated from leonardite was used as a sorbate. According to Semenov’s data, the humic product has the following elemental composition (wt %): carbon - 51.5; hydrogen - 4.2, nitrogen - 1.5, oxygen - 42.8. The ash content is 26.8% and the degree of oxidation is 0.3. The number average molecular weight is 4 kDa, and the weight average molecular weight is 16 kDa. The product contains 496 mmol(eq)/100 functional groups, including 260 carboxyl and 236 phenolic groups with pKa 4.5, 6.5, and 9.5 [

28].

Sorption procedure of humic acid (HA) on minerals. Bentonite clay, kaolinite and muscovite were treated with 10% HCl to remove calcium and magnesium carbonates. The kaolinite treated with hydrochloric acid was washed from excess acid, dried, ground in an agate mortar, and used in that form for experiments. The bentonite and muscovite treated with hydrochloric acid were washed to remove excess reagent, and a fraction <1 µm was isolated from them by the sedimentation method (precipitant was a 1 mol/L CaCl2 solution). The resulting clay fraction was washed from excess chloride ion by dialysis, dried and ground in an agate mortar, and used for subsequent experiments.

A sample of the HA product was dissolved in 5 mmol/L acetate buffer (pH = 4.5). The concentration of the working solution of HA was 100 mg/l. The resulting solution was poured into weighed samples of minerals at a ratio of solid phase: liquid equal to 1:1000 into flasks with a volume of 250 ml and shaken on a shaker for 5 h at 150 rpm. The resulting suspension was centrifuged at 489g (OS-6MTs centrifuge, Kyrgyzstan) within 15 minutes. The resulting precipitate was quantitatively transferred into porcelain cups and dried at 40°C. The dried sample was again ground in an agate mortar and the sorption–drying procedure was repeated two more times. An aliquot of the supernatant was centrifuged at 16639g (Eppendorf 5804 centrifuge, rotor FA-45-6-30, Germany) for 30 min and stored to determine amphiphilicity.

Assessing stability of the original and mineral-sorbed HA to microbial action. Samples of minerals after three sorption cycles were incubated in glass vials in the ratio of solid:liquid phase = 1:0.8 (1.5 g of the mineral : 1.2 ml of distilled H2O at 25°C in the dark in several stages: the first stage of incubation took 90 hours, the following 4 stages - 70 hours each. To determine basal respiration at the end of each incubation stage, the gas phase was taken with a syringe and the concentration of carbon dioxide in it was determined by gas chromatography on a Crystal 5000.2 chromatograph (Khromatek, Russia).

Basal respiration of the humic acid solution was measured with an OxiTop-C biological oxygen demand (BOD) manometric system in the presence of a nitrification inhibitor (allylthiourea) during the same time intervals as with minerals.

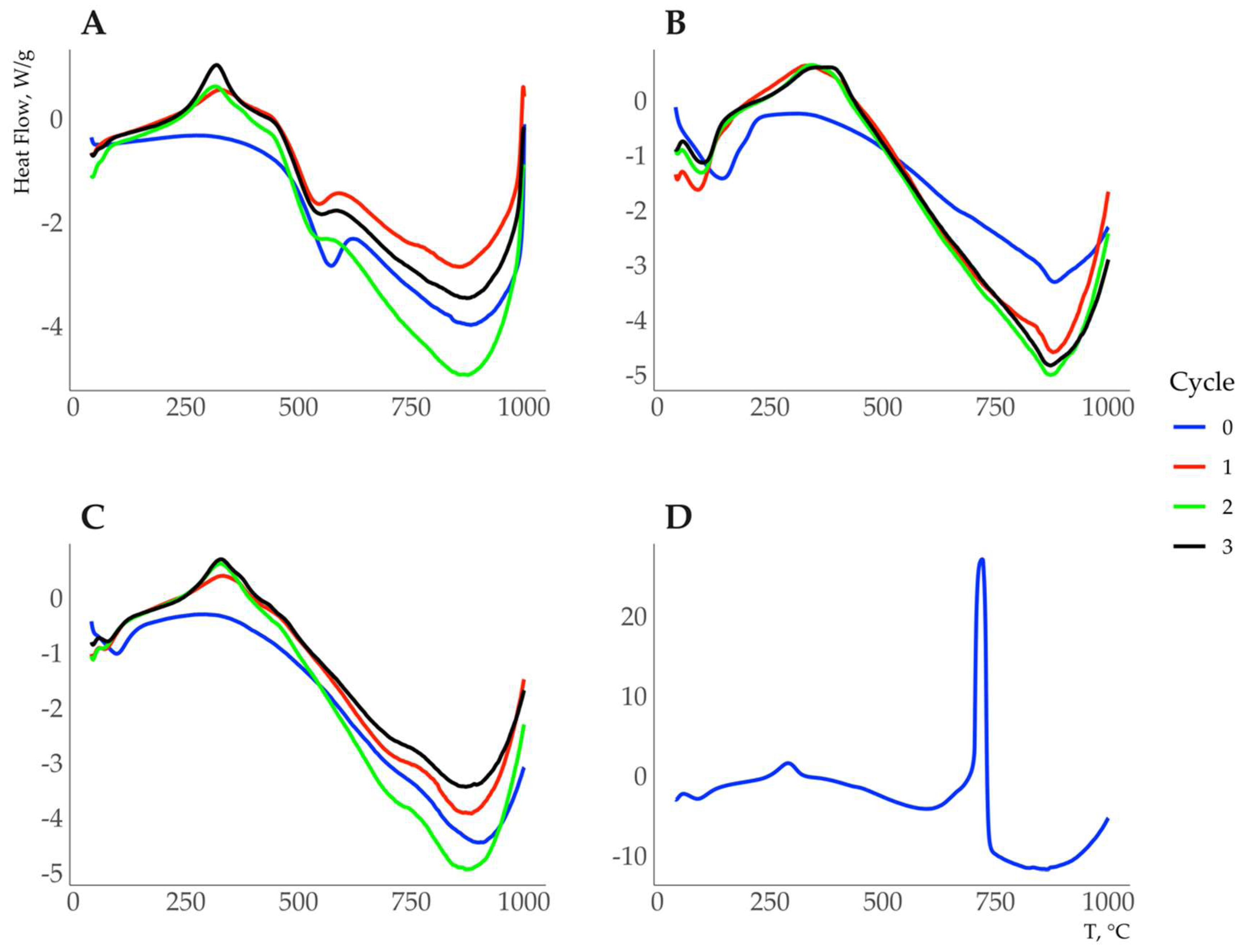

Assessing thermal stability of the original and mineral-sorbed HA. Thermal analysis was performed on a TGA/DSC 3+ synchronous thermal analyzer (Mettler Toledo, Switzerland) equipped with an o-DTA sensor that did not require a reference sample. Calibration of the device was carried out according to the temperature and melting enthalpy of certified materials - indium, zinc, aluminum and gold. The samples were taken in a synthetic air atmosphere (composition: 80% N2, 20% O2) with a gas flow rate of 60 ml/min in aluminum oxide crucibles with a volume of 70 µl, the heating rate was 10 °C/min. Before analysis, the samples were kept for several days in a desiccator over a saturated solution of calcium nitrate to maintain a constant relative humidity of 55%. The sample weight varied depending on organic matter content and was approximately 50 mg for pure minerals, 30 mg for minerals treated with HA, and 15 mg for the HA product. All measurements were carried out in duplicate. The experimental curves were processed using STARe Evaluation Software (v. 16.40).

To calculate the area of exothermic peaks, the Fityk program (v. 1.3.1) was used; the baseline was drawn by a spline function with extreme points in the regions of 150–200°С and 550–800°С [

29]. Identification of weight loss areas was carried out visually by comparing the weight loss curves with the peaks of the weight loss rate according to the DTG curves.

Amphiphilicity of HA. Amphiphilicity of HA was studied by hydrophobic chromatography on a BIOLOGIC LP chromatographic system (BIO-RAD, USA). Modified agarose Octil-Sepharose CL 4B (Pharmacia) was used as a working matrix. The following conditions were chosen for humic substance (HS) separation: column - 1.84 X 6.5 cm (BIO-RAD); buffer - 0.05 M Tris-HCI pH 7.2; sensitivity - 0.2-0.4% T; elution rate - 5 ml/h; detection was carried out at 206 nm. Linear concentration gradients of ammonium sulfate ranged from 2.0 to 0 M, detergent - from 0 to 0.3% SDS-Na. The proportion of hydrophobic and hydrophilic components was calculated from the peak areas in the chromatograms.

Elemental composition of HA. Elemental analysis was performed on a Vario EL III CHNS analyzer (Elementar, Germany) in triplicate.

Specific surface area. The surface area was determined on a Quadrasorb SI/Kr analyzer (Quantachrome Instruments, USA). Adsorption was carried out at a temperature of 77.35 K; nitrogen with a purity of 99.999% was used as the adsorbate. Helium of 99.9999% purity was used to calibrate the volume of the measuring cells. Calculation was carried out according to the BET isotherm in the P/P0 range from 0.05 to 0.30.

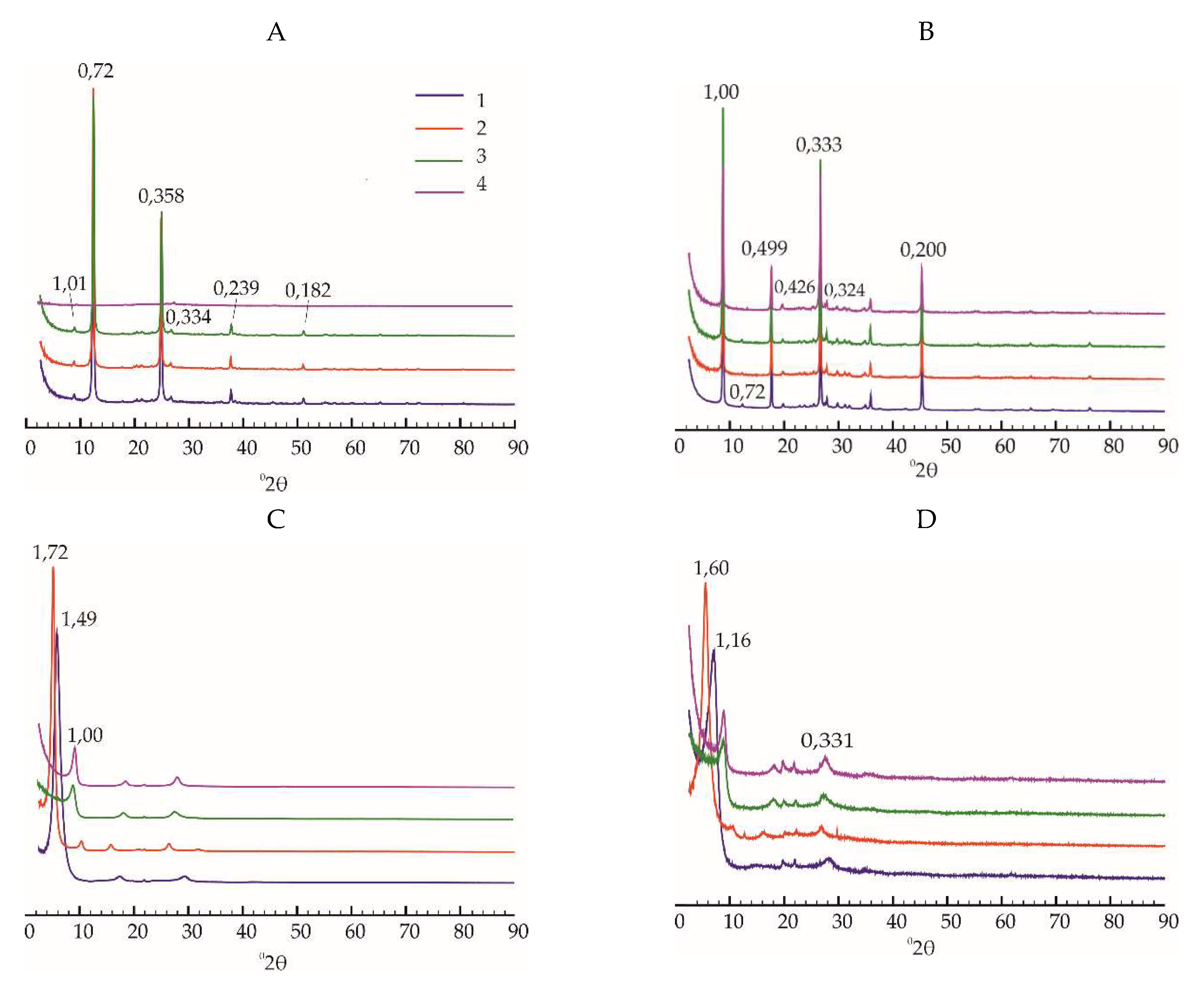

Mineral composition of sorbents. The mineral composition of sorbents was determined by X-ray diffractometry on a MiniFlex 600 diffractometer (Rigaku, Japan) in the following mode: CuKα radiation, voltage and current in the X-ray tube 30 kV and 15 mA, detector –D/teX.

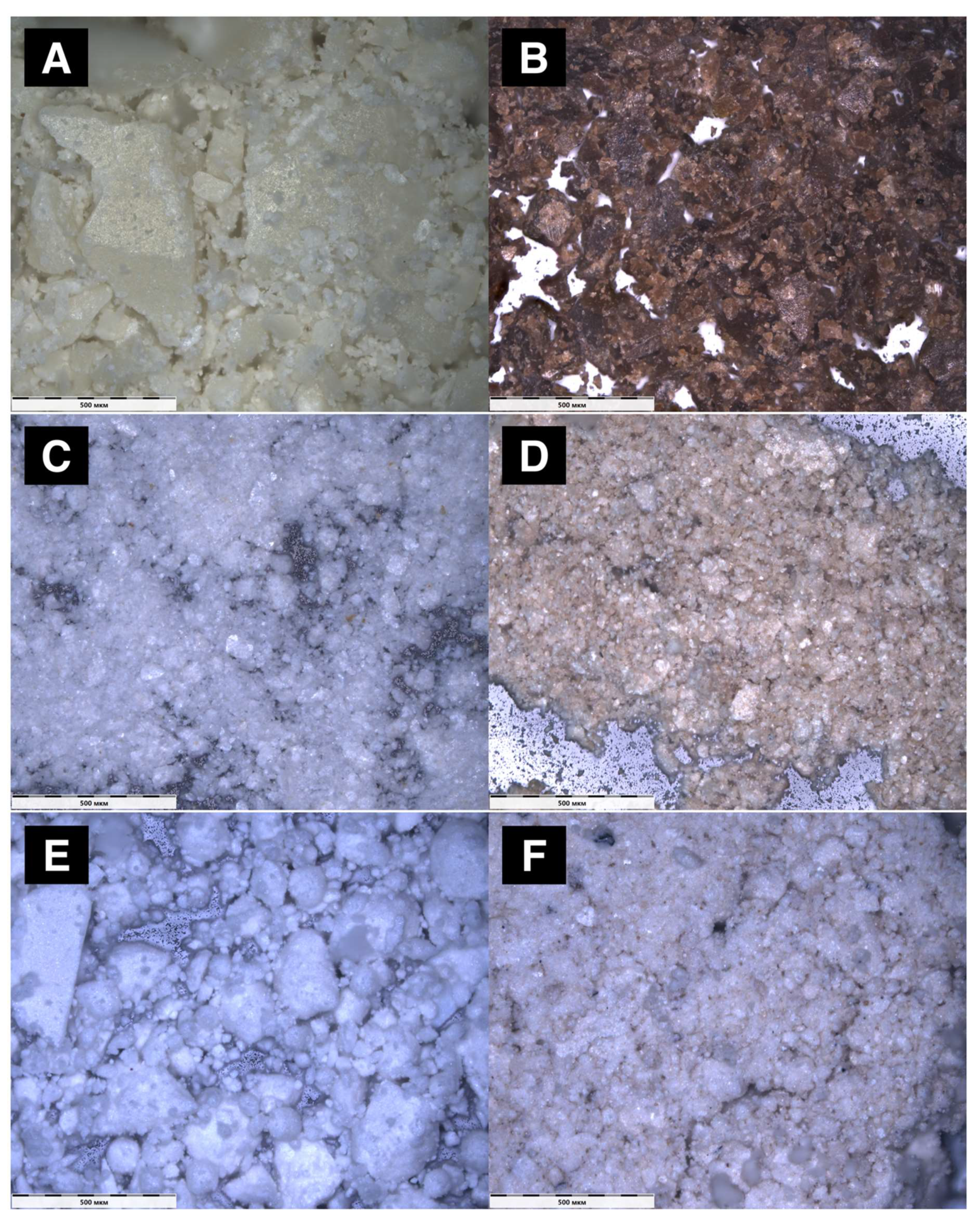

Microscopy. Studies at the micro- and submicrolevels were performed using a Soptop CX40P specialized direct polarizing optical microscope (Sunny Optical Technology, China) and a JEOL JSM-6060A scanning electron microscope (JEOL, Japan).

Data visualization. The visualization of the experimental data was conducted utilizing the R package ggplot2 [

30].

4. Discussion

Sorption regularities of HA. The DSC curve of humic acid highlights an exothermic effect of medium intensity with a maximum at 290

0C, a weak exothermic effect accompanied by weight loss with a maximum of ≈ 470

0C, and a very intense exothermic effect with a maximum at a temperature of 740

0C (

Figure 1C, Table S1). This can be explained by thermal destruction of various organic structures. According to the data obtained by the DSC, DTA, NMR, DRIFT-FTIR methods for HA whose composition is similar to the HA in our experiment, the exothermic effect at ≈300°C results from the destruction of carbohydrates and hydroxylated aliphatic structures. At ≈470°С, the destruction of polynuclear systems, long-chain hydrocarbons and nitrogen-containing substances occurs, and the products of polycondensation reaction, the most thermally stable aromatic structures, are destroyed at 700

0С [

31,

32]. The absence of a high-temperature exothermic effect at ≈ 700

0С on the DSC curves of kaolinite, bentonite, and muscovite after HA sorption at ≈ 700

0С (

Figure 1 A-C) indicates that highly condensed thermally stable aromatic substances were not sorbed on minerals under the experimental conditions.

In terms of weight unit, the largest amount of HA was sorbed on bentonite (

Table 1). The treatment of bentonite with a HA solution of pH 4.5 resulted in a partial replacement of Ca

2+ by H

+ in the interlayers of montmorillonite and a decrease in the interplanar spacing of montmorillonite from 1.49 nm for Ca-montmorillonite to 1.25 nm for H(Ca)-montmorillonite (

Figure 1 C, D). A decrease rather than an increase in the interplanar spacing of montmorillonite after HA sorption indicates that HA was sorbed on the mineral surface without intercalation into the interlayer space. The data obtained in experiments with soils also indicate that almost no HS intercalation occurs in the interlayers of montmorillonite [

4,

14].

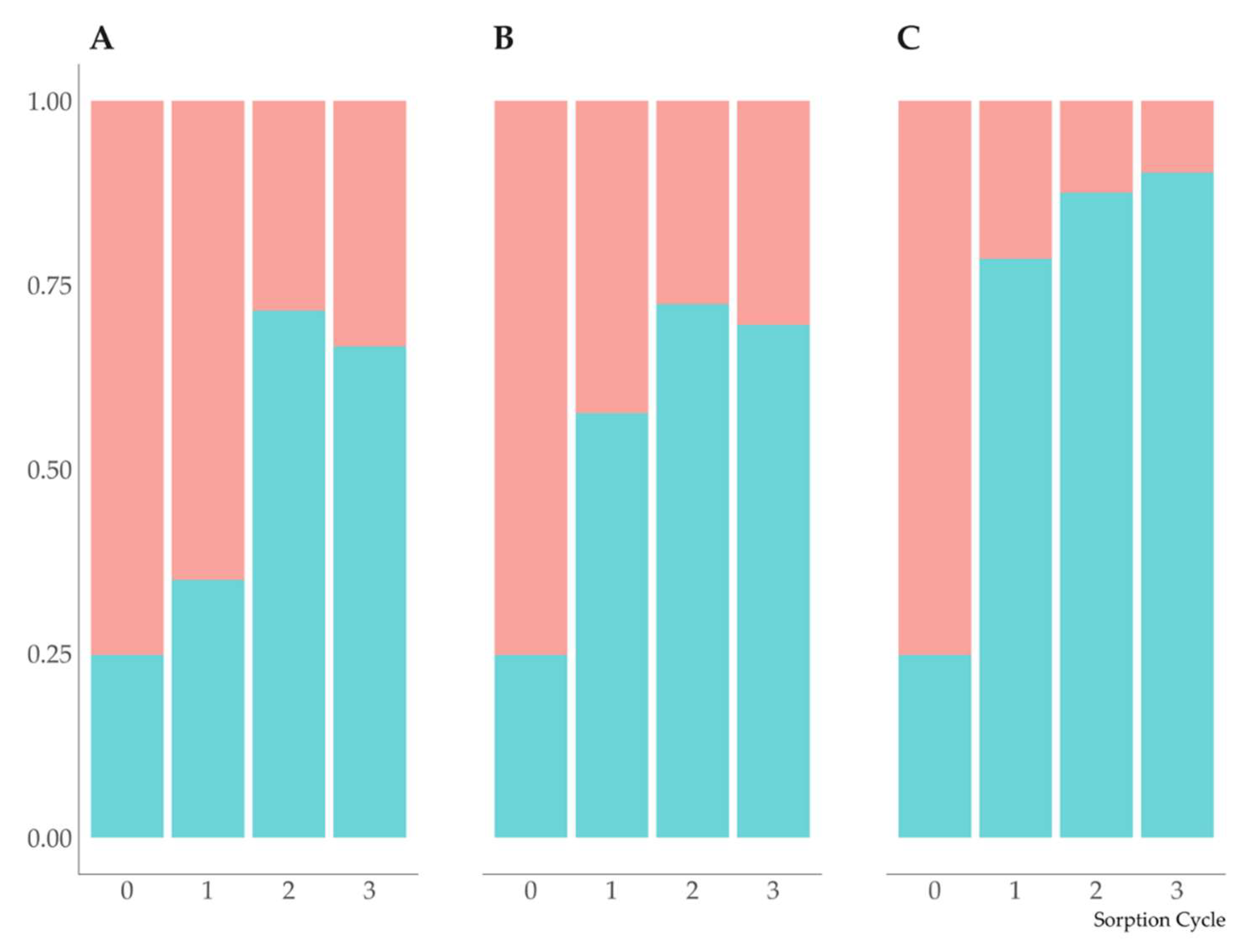

Under the conditions of our experiment, humic acid was sorbed on all minerals mainly due to hydrophobic compounds (

Figure 6). Therefore, the leading mechanism of HA sorption should be hydrophobic interactions which occur in areas of siloxane surfaces not affected by a constant negative charge of the mineral crystal lattice. The maximum amount of HAs was sorbed on kaolinite which is characterized by a low degree of isomorphic substitution in tetrahedra, hence a low layer charge per unit surface area. Bentonite, whose predominant mineral is montmorillonite with a low layer charge, sorbed less HAs per unit surface area than kaolinite. In terms of unit surface area, the least amount of HA was sorbed on muscovite which has a high negative charge in the tetrahedral network preventing hydrophobic interactions (

Table 1).

The observed decrease in the proportion of hydrophobic components in the HA solution after the second and third cycles of sorption can be explained by two factors: zoning of the organic matter distribution near the mineral surface and heterogeneity of sorption centers on the surface of the original mineral and the mineral whose surface was modified by organic matter as a result of each subsequent sorption cycle (

Figure 6). Unexpectedly, the hydrophobic fraction in the sorbed HA proved to be higher on muscovite which had less organic matter sorption due to the reasons described above. It is possible that the surface of muscovite had few hydrophobic sorption centers but they had a high selectivity. To explain this result, further research is required.

Sorption of HAs on clay minerals is accompanied by fractionation not only in amphiphilic properties, but also in chemical composition [

3,

5,

10,

33]. Kaolinite selectively sorbed the most nitrogen-depleted HA components, while bentonite and muscovite sorbed more nitrogen-containing components (

Figure 6).

Obviously, hydrophilic components of HA are also sorbed on the surface of minerals. The pH of the zero charge point (pH

PZC) for bentonite clays is about 8 units [

34,

35,

36], and the pKa of silanol and aluminol groups of montmorillonite vary from 6.7 to 8.2 and from 4.8 to 8.5, respectively [

37,

38]. The pH

PZC of the muscovite used in the experiment is 8.1 [

39]. HA sorption was carried out at pH 4.5, which was lower than the pKa for the functional groups of the pH-dependent surfaces of kaolinite, muscovite, and montmorillonite. Thus, these functional groups were partially protonated and available for the sorption of deprotonated functional groups of HA whose pK

1 was 4.5. Amino groups at pH 4.5 were protonated and positively charged; therefore, they could also be fixed on the surface of minerals through electrostatic interaction. This mechanism is more probable in the case of HA sorption on muscovite, which has a high negative charge of the layer, and on montmorillonite. The above assumptions are confirmed by the low C/N values of organic matter adsorbed on muscovite and montmorillonite (

Table 1). Bentonite, having a high cation exchange capacity and partially saturated Ca

2+, can retain HA by means of bridge bonds through the Ca

2+ ion. The obtained data allow us to conclude that hydrophobic mechanism of HA sorption is mainly implemented on kaolinite, while the sorption of HA on muscovite is mostly determined by electrostatic interactions. Bentonite sorbs HA through both mechanisms.

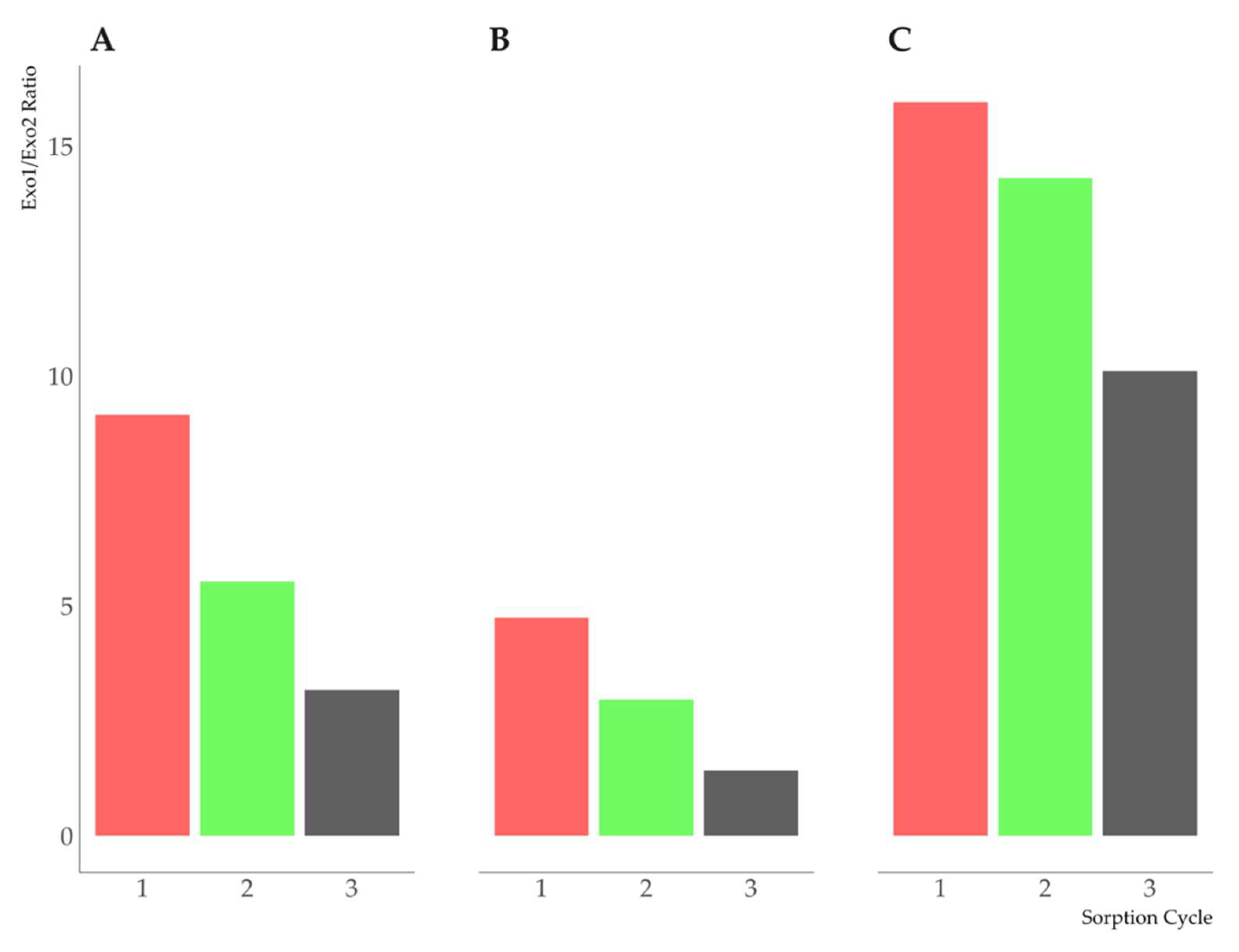

Thermal stability of HA sorbed on minerals. Increased degradation temperature of HA and decreased peak area ratio Exo1/Exo2, decreasing in the series muscovite > kaolinite > bentonite (

Figure 7), indicate an increase in more thermally stable organic matter on the surface of the solid phase compared to the initial HA. The asymmetry and bimodality of the exothermic effect of the sorbed HA destruction became most pronounced after the 3

rd sorption cycle. This can be explained both by the sorption of HA components with different thermal stability and by the change in the thermal stability of HA due to multilayer sorption. According to the literature, during sorption on mineral surfaces HS molecules do not form a uniform layer, but are concentrated in limited areas (patches). If OM is increasing, it is sorbed mainly in these areas, forming layered structures [

3,

16,

40]. In [

13]proposed a conceptual model of multilayer HA sorption on kaolinite surface areas: saturation of the first layer of sorbed HA leads to the formation of a second layer on it, resulting in conformational changes in the first one, and so on.

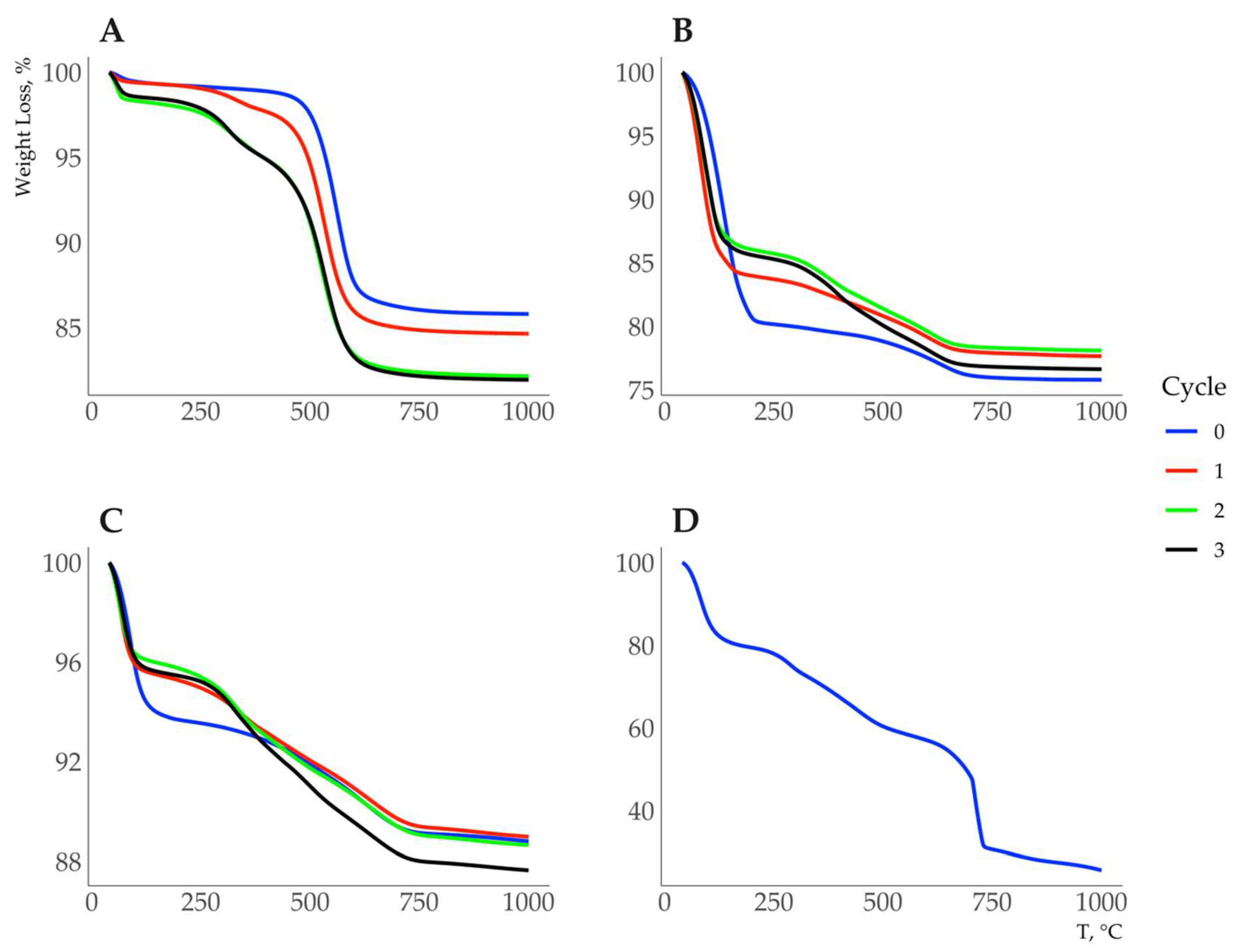

According to our experiments, thermal stability of sorbed HA does not decrease with saturation, but, on the contrary, increases (the area of the Exo2 effect increases). Probably, the maximum sorption of organic matter was not achieved under the experimental conditions. Similar results were obtained by Feng et al. [

20]. A decrease in weight loss in low-temperature regions and a corresponding increase in weight loss in high-temperature regions also indicate increased thermal stability of sorbed HA (Table S1). The results obtained can be explained by stronger fixation of HA on the surface of minerals due to the drying cycles of the experimental procedure or changed sorption properties of the mineral after forming an organomineral sorption complex [

33].

After HA sorption, position of the endothermic effects of clay minerals dehydration shifts to lower temperatures and their position on the DSC curves almost coincide with that of the initial HA. HA appears to occupy a significant surface area of the mineral crystallites and, thus, determines the hygroscopic properties of the mineral.

The shift of the endothermic effect of kaolinite (dehydroxylation) to lower temperatures from 562°C in the initial kaolinite to 540–530°C after HA sorption can be explained by the weakening of bonds in the octahedral network and a decrease in its thermal stability. However, further studies are required to confirm this assumption.

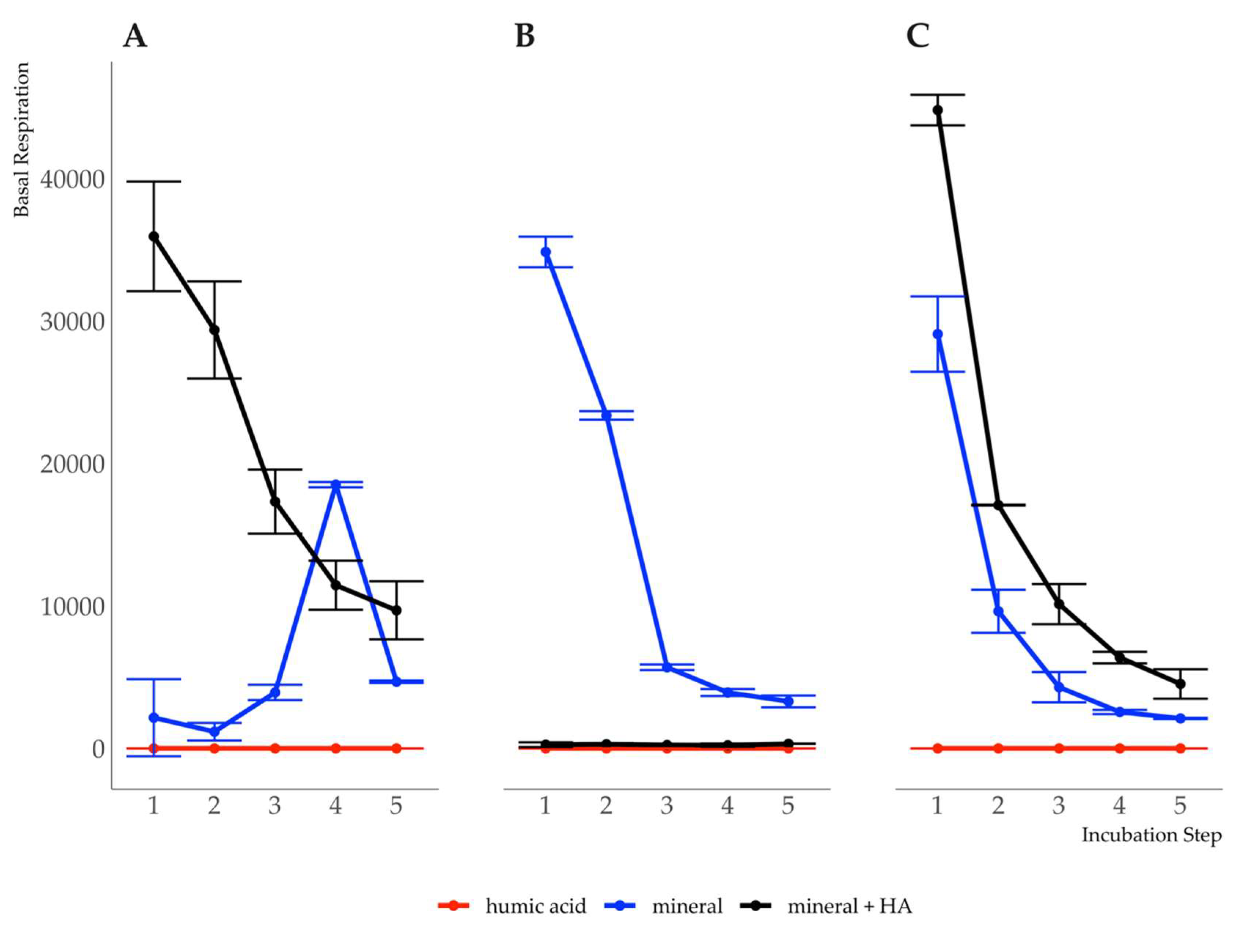

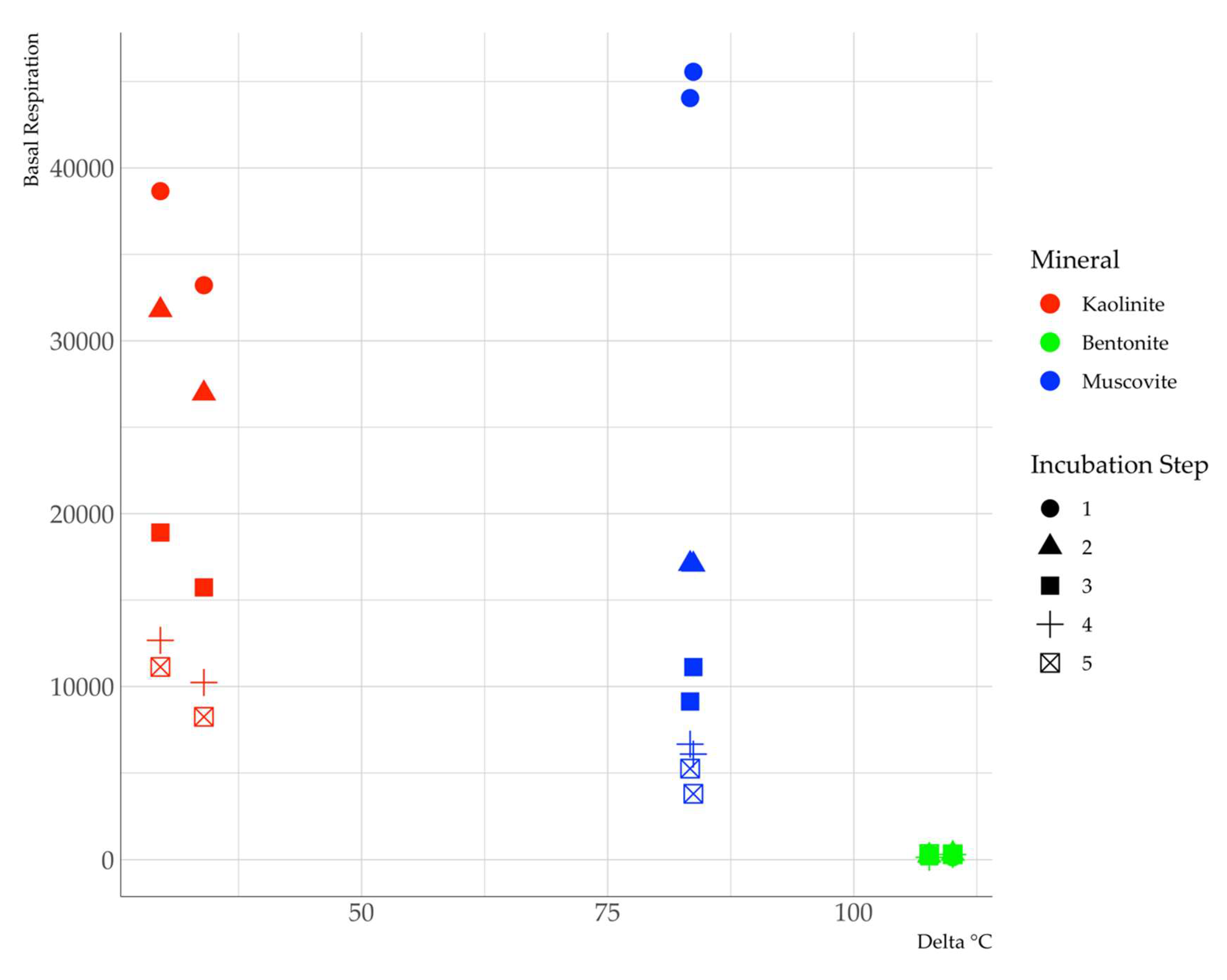

Relationship between thermal stability of HA and resistance to microbial degradation. The intensity of basal respiration on the initial bentonite and muscovite (

Figure 8) during the incubation experiment varied from 35000 to <5000 μg С-СО

2/g*h*(C, g). High vital activity of microorganisms at the first stages of the incubation experiment is explained by the availability of mineral nutrients suitable for utilization (potassium and calcium in muscovite, calcium in bentonite). Depletion of nutrient supply leads to a sharp decrease in the intensity of basal respiration at the last stages of the incubation experiment. For kaolinite, basal respiration did not exceed 5000 μg C-CO

2/g*h*(C, g) at all stages of the incubation experiment, except for a sharp increase at week 4 to 20000 μg C-CO

2/g*h*(C, g) (

Figure 8). Minimum values of basal respiration for microorganisms on kaolinite are explained by a lack of nutrients. However, a sudden burst of microbial activity requires a separate study.

The basal respiration of microorganisms on minerals with adsorbed HA changed according to other regularities. For kaolinite and muscovite, the value of basal respiration proved to be higher compared to the corresponding initial minerals, which results from the utilization of sorbed organic matter. Decreased reserves of the substrate available for utilization led to a gradual decrease in the intensity of basal respiration. In muscovite, the decrease occurred faster than in kaolinite, which allows us to conclude that organic matter is more available on muscovite than on kaolinite.

In general, an inverse relationship was found between the intensity of basal respiration and increased degradation temperature of sorbed HA relative to free HA. This indicates decreased availability of sorbed HA for destruction by microorganisms as thermal stability and, presumably, the strength of bond with the mineral surface increase (

Figure 9).

The intensity of bentonite basal respiration with sorbed HA remained minimal throughout the entire incubation experiment (no more than 500 μg C-CO2/g*h*(C, g)). The result obtained can be explained by low availability of organic matter for utilization by microorganisms. The bond between HA and montmorillonite via Ca2+ may be stronger than hydrophobic interactions on the surface of kaolinite and, to some extent, muscovite, and the electrostatic interactions are supposed to occur mostly on muscovite than on other minerals.

Figure 1.

X-ray diffraction patterns for the clay fraction of kaolinite (A), muscovite (B), bentonite (C), and bentonite+HA (D) obtained for the samples in the air-dry state (1), saturated with ethylene glycol (2), calcined at temperature 350°C (3) and 550°C (4). The numbers on the curves are d/n in nm.

Figure 1.

X-ray diffraction patterns for the clay fraction of kaolinite (A), muscovite (B), bentonite (C), and bentonite+HA (D) obtained for the samples in the air-dry state (1), saturated with ethylene glycol (2), calcined at temperature 350°C (3) and 550°C (4). The numbers on the curves are d/n in nm.

Figure 2.

DSC curves for kaolinite (A), muscovite (B), bentonite (C), and HA (D). The blue, red, green, and black colors indicate the DSC curves of the sorbents before HA sorption and after the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd sorption cycles, respectively.

Figure 2.

DSC curves for kaolinite (A), muscovite (B), bentonite (C), and HA (D). The blue, red, green, and black colors indicate the DSC curves of the sorbents before HA sorption and after the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd sorption cycles, respectively.

Figure 3.

TG curves for kaolinite (A), muscovite (B), bentonite (C), and HA (D). The blue, red, green, and black colors indicate the DSC curves of the sorbents before HA sorption and after the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd sorption cycles, respectively.

Figure 3.

TG curves for kaolinite (A), muscovite (B), bentonite (C), and HA (D). The blue, red, green, and black colors indicate the DSC curves of the sorbents before HA sorption and after the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd sorption cycles, respectively.

Figure 4.

Photos of the mineral samples at 100x magnification (A - bentonite, B - bentonite + HA, C - kaolinite, D - kaolinite + HA, E - muscovite, F - muscovite + HA).

Figure 4.

Photos of the mineral samples at 100x magnification (A - bentonite, B - bentonite + HA, C - kaolinite, D - kaolinite + HA, E - muscovite, F - muscovite + HA).

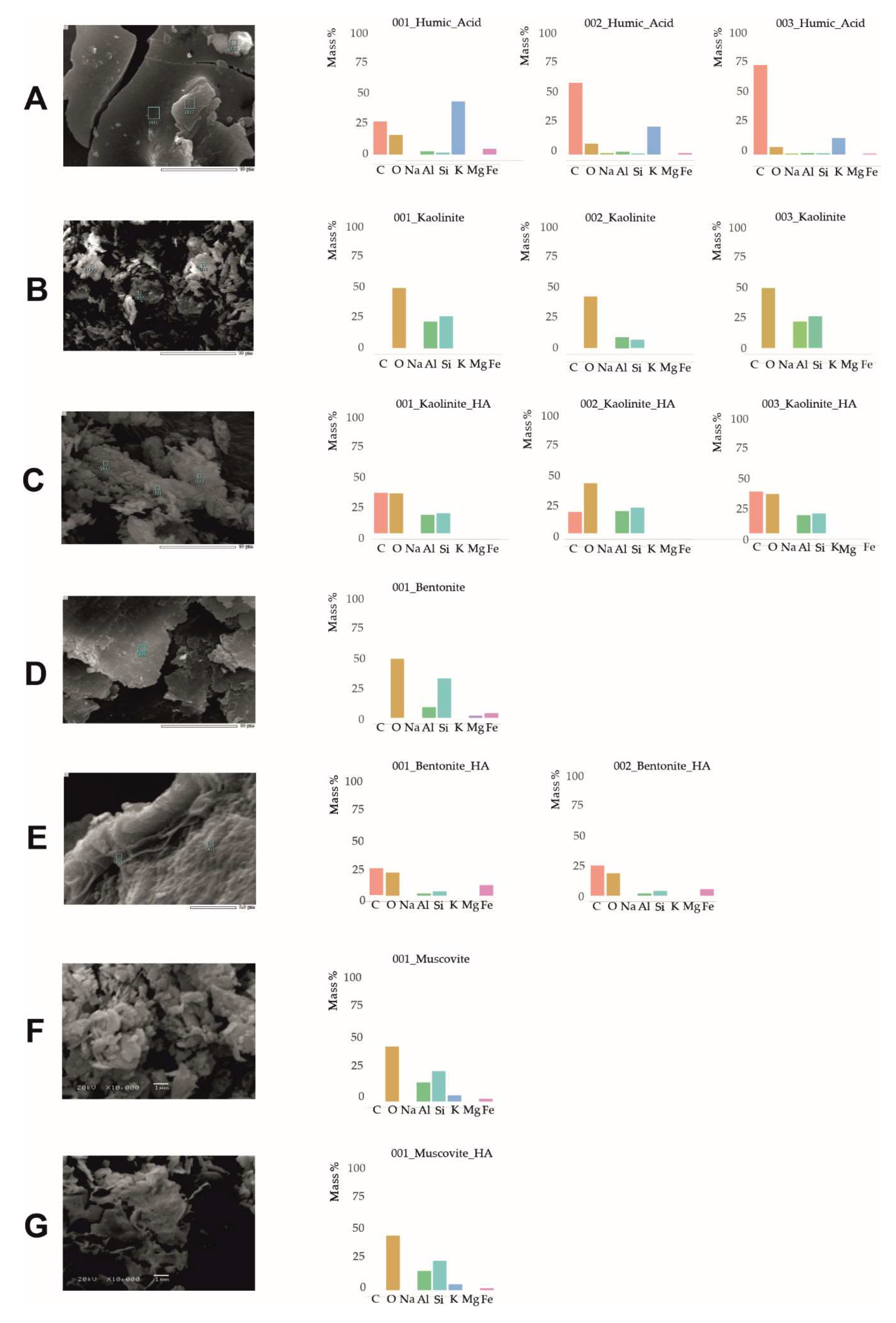

Figure 5.

SEM images of the mineral samples at 10000x magnification (A - HA, B - kaolinite, C - kaolinite + HA, D - bentonite, E - bentonite + HA, F - muscovite, G - muscovite + HA.

Figure 5.

SEM images of the mineral samples at 10000x magnification (A - HA, B - kaolinite, C - kaolinite + HA, D - bentonite, E - bentonite + HA, F - muscovite, G - muscovite + HA.

Figure 6.

Ratio of hydrophilic (green) and hydrophobic (red) components in HA solution before and after sorption on minerals (A - kaolinite, B - bentonite, C - muscovite). 0 sorption cycle corresponds to the humic acid solution.

Figure 6.

Ratio of hydrophilic (green) and hydrophobic (red) components in HA solution before and after sorption on minerals (A - kaolinite, B - bentonite, C - muscovite). 0 sorption cycle corresponds to the humic acid solution.

Figure 7.

Exo1/Exo2 peak area ratio of kaolinite (A), bentonite (B) and muscovite (C). The colors correspond to the sorption cycles.

Figure 7.

Exo1/Exo2 peak area ratio of kaolinite (A), bentonite (B) and muscovite (C). The colors correspond to the sorption cycles.

Figure 8.

Basal respiration dynamics of humic acid in its pure form (red), as part of organo-mineral complexes (black) and raw minerals (blue). The y-axis is basal respiration, µg С-СО2/g*h*(C, g), the abscissa is time intervals.

Figure 8.

Basal respiration dynamics of humic acid in its pure form (red), as part of organo-mineral complexes (black) and raw minerals (blue). The y-axis is basal respiration, µg С-СО2/g*h*(C, g), the abscissa is time intervals.

Figure 9.

Dependence of the basal respiration on the increasing temperature of sorbed HA towards an increase in relation to non-sorbed HA.

Figure 9.

Dependence of the basal respiration on the increasing temperature of sorbed HA towards an increase in relation to non-sorbed HA.

Table 1.

N and C content of HA in samples before and after HA sorption and surface characteristics of the sorbents.

Table 1.

N and C content of HA in samples before and after HA sorption and surface characteristics of the sorbents.

| Sample |

Pore volume, cm3/g |

N, % * |

C, % * |

C/N * |

S, m2/g |

С, g/m2

|

| Bentonite |

0.084 |

0.18 |

0.09 |

1.3 |

88.7 |

1.02 × 10-5

|

| Kaolinite |

0.107 |

0.12 |

0.09 |

2.1 |

18.7 |

4.81× 10-5

|

| Muscovite |

0.175 |

0.18 |

0.05 |

3.4 |

98.5 |

0.51 × 10-5

|

| HA |

ND |

0.91 |

40.35 |

44.2 |

ND |

ND |

| Bentonite+HA (1) |

ND |

0.17 |

3.18 |

18.7 |

ND |

0.35 × 10-3

|

| (2) |

ND |

0.17 |

3.01 |

17.7 |

| Kaolinite+HA (1) |

ND |

0.08 |

2.11 |

26.4 |

ND |

1.03 × 10-3

|

| (2) |

ND |

0.06 |

1.75 |

29.1 |

| Muscovite+HA (1) |

ND |

0.10 |

1.76 |

17.6 |

ND |

0.18 × 10-3

|

| (2) |

ND |

0.12 |

1.71 |

14.3 |