Submitted:

24 August 2023

Posted:

29 August 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

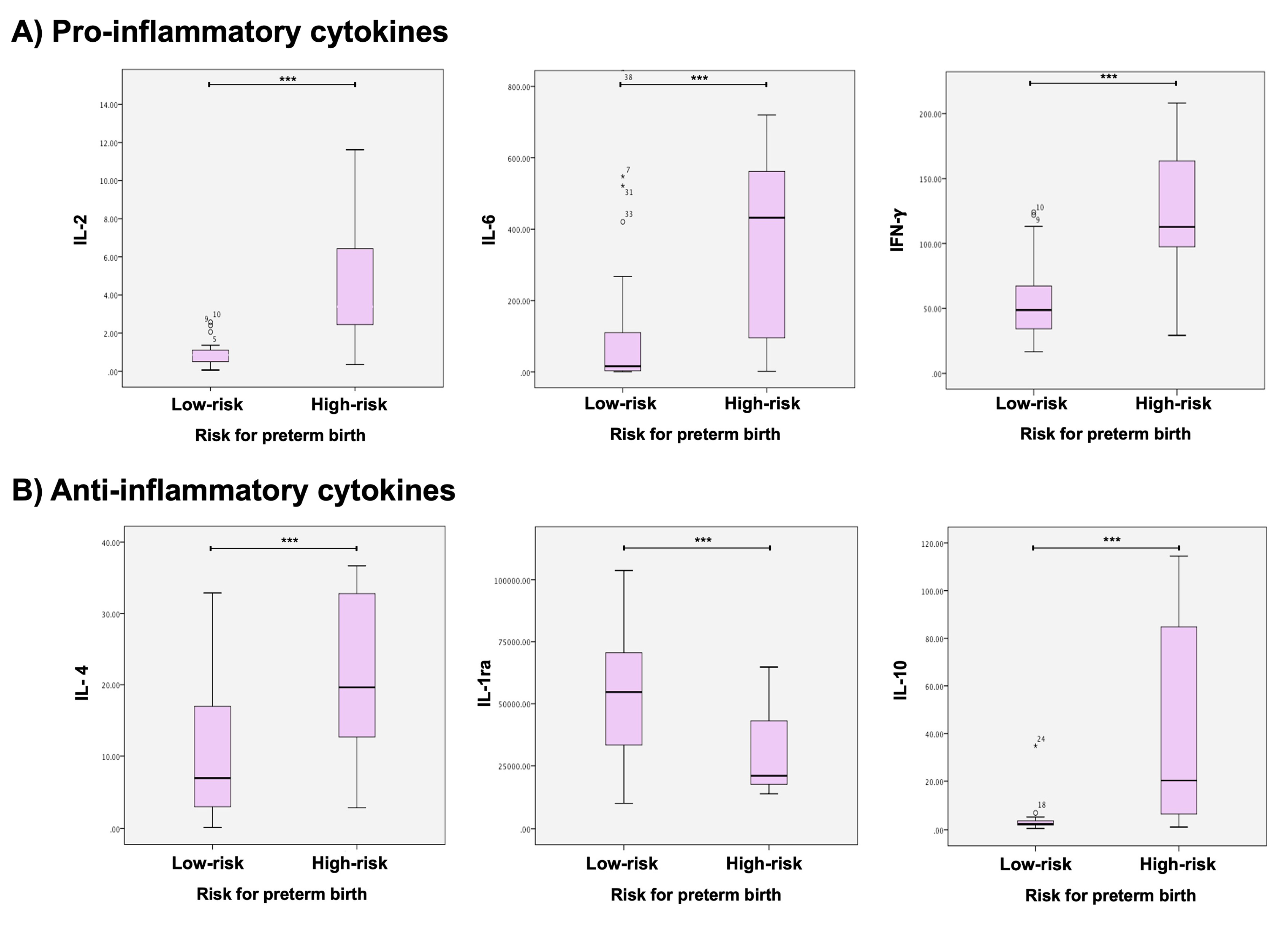

2.1. Cytokine profile in low- and high-risk for PB women

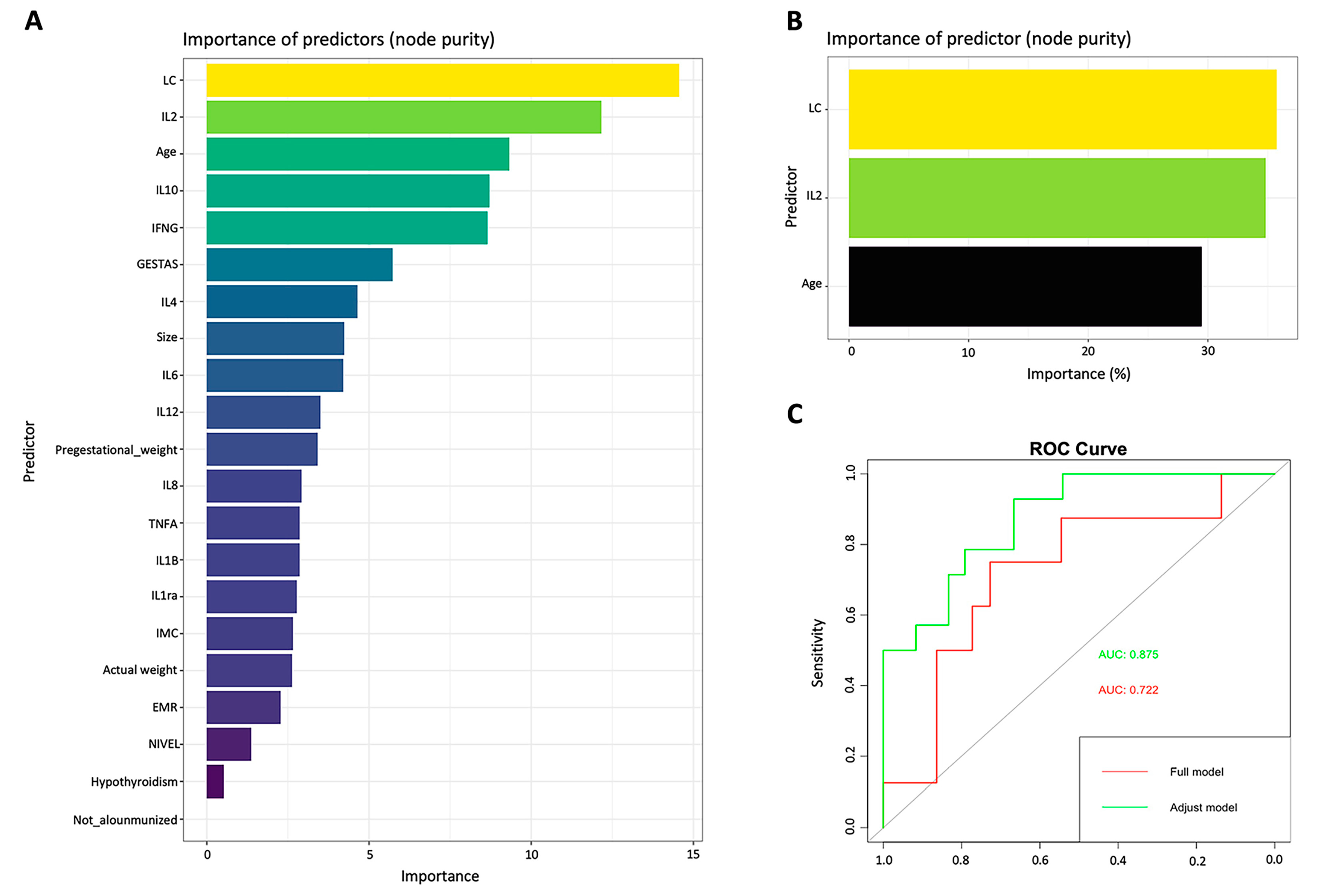

2.2. Machine learning predictive model

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethics statement

4.2. Study population

4.3. Sample collection

4.4. Cervical-vaginal cytokine quantification

4.5. Statistical analysis

4.6. Machine learning model

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Griggs, K.M.; Hrelic, D.A.; Williams, N.; McEwen-Campbell, M.; Cypher, R. Preterm Labor and Birth: A Clinical Review. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 2020, 45, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blencowe, H.; Cousens, S.; Oestergaard, M.Z.; Chou, D.; Moller, A.B.; Narwal, R.; Adler, A.; Vera Garcia, C.; Rohde, S.; Say, L.; et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet 2012, 379, 2162–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, R.; Dey, S.K.; Fisher, S.J. Preterm labor: one syndrome, many causes. Science 2014, 345, 760–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Renzo, G.C.; Tosto, V.; Giardina, I. The biological basis and prevention of preterm birth. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2018, 52, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.Q.; Fraser, W.; Luo, Z.C. Inflammatory cytokines and spontaneous preterm birth in asymptomatic women: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2010, 116, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simhan, H.N.; Bodnar, L.M.; Kim, K.H. Lower genital tract inflammatory milieu and the risk of subsequent preterm birth: an exploratory factor analysis. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2011, 25, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, B.D.; Holzman, C.B.; Fichorova, R.N.; Tian, Y.; Jones, N.M.; Fu, W.; Senagore, P.K. Inflammation biomarkers in vaginal fluid and preterm delivery. Hum Reprod 2013, 28, 942–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socha, M.W.; Flis, W.; Pietrus, M.; Wartęga, M.; Stankiewicz, M. Signaling Pathways Regulating Human Cervical Ripening in Preterm and Term Delivery. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torbé, A.; Czajka, R. Proinflammatory cytokines and other indications of inflammation in cervico-vaginal secretions and preterm delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2004, 87, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowd, J.; Laham, N.; Rice, G.; Brennecke, S.; Permezel, M. Elevated interleukin-8 concentrations in cervical secretions are associated with preterm labour. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2001, 51, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashford, K.; Chavan, N.R.; Wiggins, A.T.; Sayre, M.M.; McCubbin, A.; Critchfield, A.S.; O'Brien, J. Comparison of Serum and Cervical Cytokine Levels throughout Pregnancy between Preterm and Term Births. AJP Rep 2018, 8, e113–e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaga-Clavellina, V.; Flores-Espinosa, P.; Pineda-Torres, M.; Sosa-González, I.; Vega-Sánchez, R.; Estrada-Gutierrez, G.; Espejel-Núñez, A.; Flores-Pliego, A.; Maida-Claros, R.; Estrada-Juárez, H.; et al. Tissue-specific IL-10 secretion profile from term human fetal membranes stimulated with pathogenic microorganisms associated with preterm labor in a two-compartment tissue culture system. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2014, 27, 1320–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, E.; To, M.; Gajewska, K.; Smith, G.C.; Nicolaides, K.H. Cervical length and obstetric history predict spontaneous preterm birth: development and validation of a model to provide individualized risk assessment. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2008, 31, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.Y.; Cho, G.J.; Kwon, H.S. Applications of artificial intelligence in obstetrics. Ultrasonography 2023, 42, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arain, Z.; Iliodromiti, S.; Slabaugh, G.; David, A.L.; Chowdhury, T.T. Machine learning and disease prediction in obstetrics. Curr Res Physiol 2023, 6, 100099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Fonseca, E.B.; Damião, R.; Moreira, D.A. Preterm birth prevention. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2020, 69, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyyazhagan, A.; Kuchi Bhotla, H.; Pappuswamy, M.; Tsibizova, V.; Al Qasem, M.; Di Renzo, G.C. Cytokine see-saw across pregnancy, its related complexities and consequences. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2023, 160, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Colin, D.E.; Godines-Enriquez, M.S.; Espejel-Núñez, A.; Beltrán-Montoya, J.J.; Picazo-Mendoza, D.A.; de la Cerda-Ángeles, J.C.; Bello-Chavolla, O.Y.; Meraz-Cruz, N.; Chavira-Suárez, E.; Vadillo-Ortega, F. Cervicovaginal Cytokines to Predict the Onset of Normal and Preterm Labor: a Pseudo-longitudinal Study. Reprod Sci 2023, 30, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.W.; Park, K.H.; Lee, S.Y. Noninvasive prediction of intra-amniotic infection and/or inflammation in women with preterm labor: various cytokines in cervicovaginal fluid. Reprod Sci 2013, 20, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cetin, O.; Karaman, E.; Alisik, M.; Erel, O.; Kolusari, A.; Sahin, H.G. The evaluation of maternal systemic thiol/disulphide homeostasis for the short-term prediction of preterm birth in women with threatened preterm labour: a pilot study. J Obstet Gynaecol 2022, 42, 1972–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghella, V.; Palacio, M.; Ness, A.; Alfirevic, Z.; Nicolaides, K.H.; Saccone, G. Cervical length screening for prevention of preterm birth in singleton pregnancy with threatened preterm labor: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials using individual patient-level data. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2017, 49, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yavari Kia, P.; Baradaran, B.; Shahnazi, M.; Asghari Jafarabadi, M.; Khaze, V.; Pourasad Shahrak, S. Maternal Serum and Cervicovaginal IL-6 in Patients with Symptoms of Preterm Labor. Iran J Immunol 2016, 13, 229–236. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, N.; Bonifacio, L.; Reddy, P.; Hanna, I.; Weinberger, B.; Murphy, S.; Laskin, D.; Sharma, S. IFN-gamma-mediated inhibition of COX-2 expression in the placenta from term and preterm labor pregnancies. Am J Reprod Immunol 2004, 51, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxton, M.A.; Meraz-Cruz, N.; Sanchez, B.N.; Foxman, B.; Castillo-Castrejon, M.; O'Neill, M.S.; Vadillo-Ortega, F. Timing of Cervico-Vaginal Cytokine Collection during Pregnancy and Preterm Birth: A Comparative Analysis in the PRINCESA Cohort. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, P.; Chiasson, V.L.; Bounds, K.R.; Mitchell, B.M. Regulation of the Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines Interleukin-4 and Interleukin-10 during Pregnancy. Front Immunol 2014, 5, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Park, C.W.; Lockwood, C.J.; Norwitz, E.R. Role of cytokines in preterm labor and birth. Minerva Ginecol 2005, 57, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Liu, Z.; Huang, D.; Ran, Y.; Zhang, H.; He, J.; Yin, N.; Qi, H. IL-37 Exerts Anti-Inflammatory Effects in Fetal Membranes of Spontaneous Preterm Birth via the NF-κB and IL-6/STAT3 Signaling Pathway. Mediators Inflamm 2020, 2020, 1069563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman-Sachs, A.; Dambaeva, S.; Salazar Garcia, M.D.; Hussein, Y.; Kwak-Kim, J.; Beaman, K. Inflammation induced preterm labor and birth. J Reprod Immunol 2018, 129, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goepfert, A.R.; Goldenberg, R.L.; Andrews, W.W.; Hauth, J.C.; Mercer, B.; Iams, J.; Meis, P.; Moawad, A.; Thom, E.; VanDorsten, J.P.; et al. The Preterm Prediction Study: association between cervical interleukin 6 concentration and spontaneous preterm birth. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001, 184, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challis, J.R.; Lockwood, C.J.; Myatt, L.; Norman, J.E.; Strauss, J.F., 3rd; Petraglia, F. Inflammation and pregnancy. Reprod Sci 2009, 16, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paternoster, D.M.; Stella, A.; Gerace, P.; Manganelli, F.; Plebani, M.; Snijders, D.; Nicolini, U. Biochemical markers for the prediction of spontaneous pre-term birth. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2002, 79, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmo, F.R.; Alves, E.A.R.; Moreira, R.A.A.; Severino, V.O.; Rocha, L.P.; Monteiro, M.; Reis, M.A.D.; Etchebehere, R.M.; Machado, J.R.; Corrêa, R.R.M. Intrauterine infection, immune system and premature birth. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2018, 31, 1227–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.J.; Humphries, S.E. Cytokine and cytokine receptor gene polymorphisms and their functionality. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2009, 20, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, L.F.; Chaiworapongsa, T.; Romero, R. Intrauterine infection and prematurity. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 2002, 8, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsuyama, K.; Matsumoto, S.; Rose-John, S.; Suzuki, A.; Hara, T.; Tomiyasu, N.; Handa, K.; Tsuruta, O.; Funabashi, H.; Scheller, J.; et al. STAT3 activation via interleukin 6 trans-signalling contributes to ileitis in SAMP1/Yit mice. Gut 2006, 55, 1263–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffen, S.L.; Liu, K.D. Overview of interleukin-2 function, production and clinical applications. Cytokine 2004, 28, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-de-la-Rosa, M.; Rebollo, F.J.; Codoceo, R.; Gonzalez Gonzalez, A. Maternal serum interleukin 1, 2, 6, 8 and interleukin-2 receptor levels in preterm labor and delivery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2000, 88, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.L.; Zhou, X.Y.; Xu, N.X.; Chen, S.C.; Xu, C.M. Association of IL-4 and IL-10 Polymorphisms With Preterm Birth Susceptibility: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 917383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, M.; Zenclussen, A.C. IL-10 Producing B Cells Protect against LPS-Induced Murine Preterm Birth by Promoting PD1- and ICOS-Expressing T Cells. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, I.; Goepfert, A.R.; Thorsen, P.; Skogstrand, K.; Hougaard, D.M.; Curry, A.H.; Cliver, S.; Andrews, W.W. Early second-trimester inflammatory markers and short cervical length and the risk of recurrent preterm birth. J Reprod Immunol 2007, 75, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertini, A.; Salas, R.; Chabert, S.; Sobrevia, L.; Pardo, F. Using Machine Learning to Predict Complications in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2021, 9, 780389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammad, N.S.; Nazli, R.; Zafar, H.; Fatima, S. Effects of lipid based Multiple Micronutrients Supplement on the birth outcome of underweight pre-eclamptic women: A randomized clinical trial. Pak J Med Sci 2022, 38, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saberi-Karimian, M.; Khorasanchi, Z.; Ghazizadeh, H.; Tayefi, M.; Saffar, S.; Ferns, G.A.; Ghayour-Mobarhan, M. Potential value and impact of data mining and machine learning in clinical diagnostics. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2021, 58, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oskovi Kaplan, Z.A.; Ozgu-Erdinc, A.S. Prediction of Preterm Birth: Maternal Characteristics, Ultrasound Markers, and Biomarkers: An Updated Overview. J Pregnancy 2018, 2018, 8367571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, A.V.; Manuck, T.A. Screening for spontaneous preterm birth and resultant therapies to reduce neonatal morbidity and mortality: A review. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2018, 23, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.Y.; Park, J.W.; Ryu, A.; Lee, S.Y.; Cho, S.H.; Park, K.H. Prediction of impending preterm delivery based on sonographic cervical length and different cytokine levels in cervicovaginal fluid in preterm labor. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2016, 42, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, J.E. Progesterone and preterm birth. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2020, 150, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.S.; Ahn, K.H. Artificial Neural Network Analysis of Spontaneous Preterm Labor and Birth and Its Major Determinants. J Korean Med Sci 2019, 34, e128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giouleka, S.; Tsakiridis, I.; Kostakis, N.; Koutsouki, G.; Kalogiannidis, I.; Mamopoulos, A.; Athanasiadis, A.; Dagklis, T. Preterm Labor: A Comprehensive Review of Guidelines on Diagnosis, Management, Prediction and Prevention. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2022, 77, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Low Risk for Preterm Delivery (n = 40) |

High Risk for Preterm Delivery (n = 20) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 29 (±7.1) | 31 (±5.8) | 0.25 |

| Pregestational weight (Kg) | 63.7 (±13.7) | 67.8 (±13.5) | 0.08 |

| Pregestational BMI (Kg/m2) | 25.2 (±5.4) | 27.5 (±5.3) | 0.12 |

| Socio-economic level median (Minimum and maximum value) |

2 (1–4) | 2 (1–5) | 0.12 |

| Smoking n (%) | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 0.45 |

| History of preterm delivery n (%) |

0 (0) | 8 (40) | 0.01 |

| Gestational age at time of cervical length measurement, (weeks of gestation) | 21.0 (±1.5) | 21.2 (±2.0) | 0.25 |

| Cervical length (mm) | 33.8 (±5.8) | 13.1 (±7.7) | 0.02 |

| Cytokine | Risk group for preterm birth |

Mean ± SD pg/ml |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pro-inflammatory cytokines | |||

| IL-1β | High-Risk | 763.87 (±1505.99) | 0.814 |

| Low-Risk | 587.94 (±1432.56) | ||

| IL-2 | High-Risk | 5.63 (±6.07) | 0.001 |

| Low-Risk | 3.60 (±14.80) | ||

| IL-6 | High-Risk | 856.29 (±1.98) | 0.001 |

| Low-Risk | 118.32 (±0.48) | ||

| IL-8 | High-Risk | 5882.35 (±5638.79) | 0.381 |

| Low-Risk | 9695.78 (±11,070.29) | ||

| IL-12 | High-Risk | 0.49 (±0.49) | 0.304 |

| Low-Risk | 0.34 (0.29) | ||

| TNF-α | High-Risk | 104.17 (±74.62) | 0.115 |

| Low-Risk | 78.63 (±50.32) | ||

| IFN-γ | High-Risk | 117.49 (±53.42) | 0.001 |

| Low-Risk | 54.17 (±26.37) | ||

| Anti-inflammatory cytokines | |||

| IL-4 | High-Risk | 20.98 (±10.78) | 0.001 |

| Low-Risk | 10.83 (±8.92) | ||

| IL-10 | High-Risk | 40.44 (±41.23) | 0.001 |

| Low-Risk | 3.56 (±5.22) | ||

| IL-1ra | High-Risk | 29768 (±17,596) | 0.002 |

| Low-Risk | |||

| Random Forest “Full model” | Random Forest “Adjust model” | Fetal Medicine Foundation Calculator | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted | Real | Predicted | Real | Predicted | Real | |||

| Term | Preterm | Term | Preterm | Term | Preterm | |||

| Term | 14 | 6 | Term | 20 | 1 | Term | 36 | 4 |

| Preterm | 2 | 1 | Preterm | 2 | 7 | Preterm | 7 | 13 |

| Detection rate | 65% | Detection rate | 87.7% | Detection rate | 79% | |||

| False positive rate | 12% | False positives rate | 3.33% | False positives rate | 6.6% | |||

| False negative rate | 28% | False negatives rate | 6.66% | False negatives rate | 11.66% | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).