1. Introduction

Influenced by factors such as advanced educational technologies, the introduction of the internet, and the global crisis brought by the COVID-19 pandemic, the educational system in higher education institutions (HEIs) is one of the most challenged institutions to shift from the conventional classes to a more flexible system of distance modality through online learning [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

Online learning is used interchangeably with distance education, online course, and e-learning [

7]. E-learning refers to an innovative web-based system supported by digital technologies and other forms of educational materials to primarily provide students with a personalized, learner-centered, open, enjoyable, and interactive learning engagement, thus, supporting and enhancing the learning process [

8]. Consequently, online education allows learners to develop knowledge and skills flexibly and conveniently [

9] that play a crucial role for online learning, and among these include the student’s engagement [

10], self-regulated learning [

11], and self-efficacy [

12].

1.1. Student Engagement

[

13] defined student engagement (SE) as ‘the investment of time, effort and other relevant resources by both students and their institutions intended to optimize the student experience and enhance the learning outcomes and development of students and the performance, and reputation of the institution’ (p. 2). SE is beneficial to students who take responsibility for their own learning, making their own decisions about what, when, and how they will engage in their studies [

14]. Hence, student engagement results from students’ involvement in learning that, in turn, affects their learning and maintains their involvement in coursework [

15]. According to [

16], student engagement as one of the most important online instructional strategies.

Empirical studies showed the critical role of student engagement in an online learning environment (OLE). [

10] concentrated on engagement strategies, including student–content, student-student, and student-teacher strategies. Among these strategies, students perceived student-content (e.g., screen sharing, summaries, & class recordings) as the most effective. The other two strategies, student–teacher strategies (e.g., Q & A sessions and reminders), are found to be more effective than the student–student strategies (e.g., group chat & collaborative work) which are perceived as least effective.

The findings on student-teacher strategies may be associated with [

17] findings on students’ online learning as engaging when they feel the instructors’ presence through social, managerial, & technical facilitation in online instruction. Meanwhile, online facilitators perceived that online discussions contributed to the improvement of SE in OLE [

18]. In addition, authors’ reflection narrated that improvement in student engagement occurs when teachers use pedagogical strategies using various virtual materials such as gamified learning tools like Kahoot and Socrative [

19].

Apparently, the findings on student-student strategies are contrary to [

20] study, claiming that an online forum during asynchronous online learning is effective in SE, especially when students respond to peers’ posts or when asked to relate topics to their personal experiences. In addition, regular interaction encourages active engagement among virtual students that, in turn, push them to complete online modules and collaboration through group tasks, which is beneficial for building knowledge in OLE [

21].

1.2. Self-Regulated Learning

Self-regulation refers to using personal strategies to control learning involving learners’ motivational, cognitive, and behavioral aspects to achieve their specified learning goals [

22]. Hence, self-regulated learning (SRL) strategies play an essential role in one’s desire to achieve learning [

23]. SRL may include students’ goal setting, time management, task strategies, environment structuring, and help-seeking. Because students desire to achieve learning, they use specific SRL skills and strategies to perform their tasks. SLR kills and strategies have a dual purpose in differentiating among individuals concerning academic achievement and enhancing academic achievement outcomes [

23]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, self-regulated learning greatly influences the success of online learning [

11,

24].

Noteworthy, empirical findings showed that students with low SRL are less likely to regulate distance learning activities during the COVID-19 pandemic [

11]. Likewise, other studies showed that some students encountered difficulties in studying at home during the pandemic because of their inability to self-regulate, considering they perceived autonomy as a burden and having no self-accountability [

25,

26].

According to [

23], virtual students vary depending on the self-regulation strategies they apply to learn online. Their study revealed five distinct profiles of virtual students: super self-regulators, competent self-regulators, forethought-endorsing self-regulators, performance/reflection self-regulators, and non- or minimal self-regulators. This finding correlates with student differences in their academic achievement. Among the profiles, the authors emphasized that non- or minimal self-regulators have poor learning outcomes.

Meanwhile, some authors discovered that students exhibit different SRL strategies in learning science education in OLE. The results of their study developed systems that help identify and support students who struggle in active learning, particularly in science education [

27]. For instance, [

28] employed a metacognitive-based learning materials to teach a chemistry lesson among pre-service teachers and determined their self-regulated learning. Findings revealed students has high criteria and very high in learning chemistry in terms of their self-motivation, belief task analysis, self-control, self-observation, self-judgment, and self-reaction.

Furthermore, other scholars investigated how the different SRL factors affect academic performance. [

29] focused on SRL factors such as goal-setting, environment structuring, computer self-efficacy, social dimension, and time management. The authors claim that among these five factors, environment structuring, computer self-efficacy, social dimension, and time-management impact students’ academic performance, whereas goal-setting is not significant. In contrast, the study by [

30] suggests that in a flipped learning setting, none of the SRL strategies (study strategies, metacognition, self-talk, interest enhance, environment structuring, self-consequating effort, and help-seeking) predict students’ achievement after conducting a multiple regression analysis. In the study by [

31], they regarded students’ performance in OLE regarding interaction with others, particularly the variable explaining their SR. The result study showed that teachers’ scaffolding influenced how students interact with their instructors and peers. Indeed, SRL of students plays a crucial role in their learning success, especially when they study at their own pace with minimal or without teacher’s presence.

1.3. Self-Efficacy

Bandura (1977) defined self-efficacy as a quality that affects an individual’s judgment of him/herself and how his/her behavior emerges, about his/her capacity to organize the necessary activities to carry out a specific performance and to do it successfully [

32]. Moreover, Bandura (1977) expresses self-efficacy as an individual’s beliefs regarding how well he/she can perform the actions required to deal with potential situations. Based on these definitions, developing individuals’ beliefs regarding how well they will carry out the activities they need to perform concerning a specific aim may also affect their performances. [

33] emphasizes that self-efficacy involves an individual’s judgments of his/her ability to carry out and succeed in a task.

Some scholars attempted to examine students’ self-efficacy and their perceived competency on a certain learning experience. For instance, [

34] investigated student-teachers’ perceived self-efficacy over their digital competency, particularly on maintaining discipline and its influence on students’ use of ICT. Two notable findings revealed that students’ teachers’ instructional efficacy is positively related to their perceived digital competency and positive attitude as substantiated by the association seen in their model. However, the researchers stipulated that they found significant association in the former but not in the latter.

Meanwhile, other researchers investigated SE together with other factors such as self-regulation and self-directedness. For instance, [

9] examined self-efficacy, self-regulation, and self-directedness predicted persistence among first-year students and tertiary non-traditional online learners. [

12] studies the characteristics of online learning success in which results revealed that computer self-efficacy also plays a key role in the process. In addition, [

35] examined the students’ SE and SRL skills in online learning. The findings suggest that self-efficacy & task value are significant predictors of SRL in students’ online learning environment.

1.4. Research Gap

Noteworthy, the studies mentioned earlier were conducted in other countries. In the Philippines, [

36] conducted a quasi-experimental study to explore students’ self-efficacy and engagement together with other variables such as knowledge gain and perception relative to the use of home-based biology experiments. Findings revealed that the intervention has a significant influence on improving students’ self-efficacy, engagement, knowledge gain and perception. However, studies to characterize Filipino online learners seem lacking, particularly their OSE, SRL, and OLSE. This is likely because the Philippines has recently implemented online distance learning to continue teaching-learning despite difficult times during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, this study is motivated to determine whether Filipino online learners also exhibit the characteristics indicated in OSE, SRL, and OLSE scales. Accordingly, this study is conducted to answer the following research questions (RQs):

Student Engagement (OSE);

Self-Regulated Online Learning (SROL); and

Online Learning Self-efficacy (OLSE)?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study used a survey research design employed through an ex post facto approach. The unprecedented event in the education system due to COVID-19 pandemic has been the pressing reason for schools to use online learning modality yet, in the Philippines, scholars and education policy-makers do not have the idea about students’ online learning profile, particularly among science education students in the tertiary level. According to [

37] a research uses ex post facto to study any causal relationship between events and circumstances or the effect of any single variable. Hence, ex post facto was employed to determine the effects of the demographic profile on the constructs OSE, SROL, and OLSE.

2.2. Research Sampling and Participants

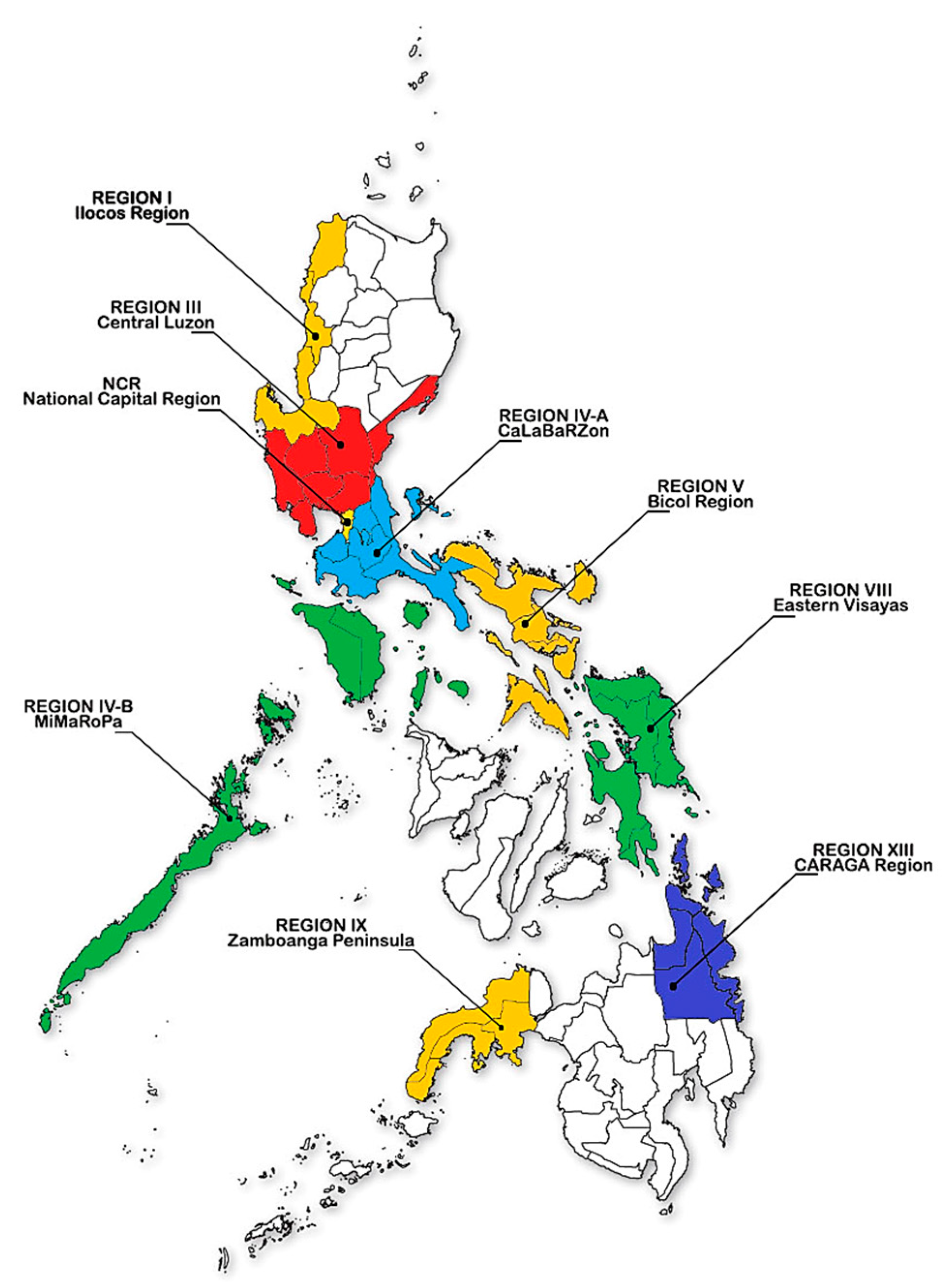

This study utilized convenience sampling. Respondents included a total of N=373 tertiary students from 9 regions in the Philippines (National Capital Region, Region I-Ilocos Regions, Region III- Central Luzon, Region IV-A - CALABARZON, Region V- Bicol Region, Region VIII- Eastern Visayas, Region IX- Zamboanga Peninsula, Region XIII- CARAGA Region, MIMAROPA). The researchers ensured these students were enrolled in science education courses taken via online learning.

Figure 1 shows the locale of the study.

2.3. Research Instruments

The researchers prepared the survey questionnaire in Google Forms. It was composed of four sections, namely (1) profile of student participant, (2) online student engagement (OSE) scale, (3) self-regulated online learning (SROL) skills, and (4) online learning self-efficacy (OLSE) scale. The profile variables asked in the first part were age group, gender preference, internet access, internet signal, region of residence, gadgets used in online learning, most preferred time to study online, and the online learning tools they use. The OSE scale is answerable by a 5-point Likert scale represented as 5- very characteristic of me, 4- characteristic of me, 3- moderately characteristic of me, 2- not really characteristic of me, and 1- not at all characteristic of me. Another 5-point Likert scale was used to answer the third part on SROL skills where 5- very true for me, 4- true for me, 3- moderately true for me, 2- rarely true for me, and 1- not at all true for me. Meanwhile, the fourth part, relating to OLSE, was answerable with a 4-point Likert scale where 4- strongly agree, 3-agree, 2-disagree, and 1-strongly disagree. The indicators used in parts 2, 3, and 4 were adopted from [

38,

39,

40], respectively. Noteworthy, OSE is adopted in observance of the fair use of the instrument, whereas the SROL and OLSE are adopted from articles retrieved from open access databases which contents are licensed under creative commons attribution 4.0.

2.4. Data Gathering and Ethics

Using email and Facebook Messenger, the researchers sent the survey questionnaire to science education teachers known to the researchers who teach at various higher education institutions in the Philippines. Noteworthy, the researchers ensured that respondents voluntarily participated in this study by providing informed consent in the preliminary part of the Google Form. It informed them of the nature of their participation, the study’s objectives, the confidentiality of their identity in observance of the Philippine Data Privacy Act of 2012, and the treatment of the data collected from them. At the end of the form, all respondents needed to tick a Yes/No question to participate in the study voluntarily. The survey lasted for three weeks. Of the total number of respondents (N=373), only one answered no and withdrew from participation, while the remaining 372 continued and submitted a fully accomplished questionnaire.

2.5. Data Analysis

Both descriptive and inferential statistics were conducted to analyze the data from the survey questionnaire. Responses then underwent an exploratory data analysis to determine the appropriate descriptive statistics. The researchers included descriptive statistics such as mean, frequency, and standard deviation. To address the research question on determining the effects of the multiple profile variables to the 3 dependent variables (OSE, SROL, OLSE), one important consideration includes the assumptions for testing MANOVA. Specifically, this research selected a factorial MANOVA test to determine the significant difference among the demographic profile relative to their effect on the dependent variables.

2.6. Assumptions for MANOVA

The researchers considered the tests for assumptions to determine whether or not Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) will be employed. Specifically, MANOVA tests need continuous and categorical data for dependent and independent variables, respectively. In this study, the dependent variables were the OSE, SRL, and OLSE Likert scale responses were considered continuous. According to [

41], continuous variables are usually used in assigning values in social sciences, such as the Likert scale whereas, the profile variables are all categorical and observations are independent thereby, meeting the assumptions for the levels and nature of data. In terms of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy, the result showed a value greater than 0.6, indicating that the assumption was met. In testing the univariate outliers, the Box Plots revealed that outliers exist in the data for age group and region of residence, so only the profile variables gender, internet access and signal, laptop and desktop for gadgets, and time to study online were considered in the following steps. As regards the dependent variables (OSE, SRL, and OLSE), outliers all discovered were disregarded which resulted to 359 samples included in further analysis. The Mahalanobis distance revealed that no multivariate outliers were observed among the remaining profile and dependent variables thereby meeting the assumption. Furthermore, in testing the linear relationship, the results of Barlett’s test of sphericity revealed that the assumptions were met since p < 0.05. Moreover, the Box test of equality of covariance matrices showed that the assumption was met with p > 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Profile

Table 1 shows the profile variables of the student-respondents. Notice that the majority are 18-22 years old (n=350, 94.09%) and most are men (n=183, 49.19%). In terms of internet connection, the majority has internet access via home broadband with a good signal (> 40%). Also, the majority are from NCR (n=183, 49.19%), and most of them studies at night (n=173, 46.51%).

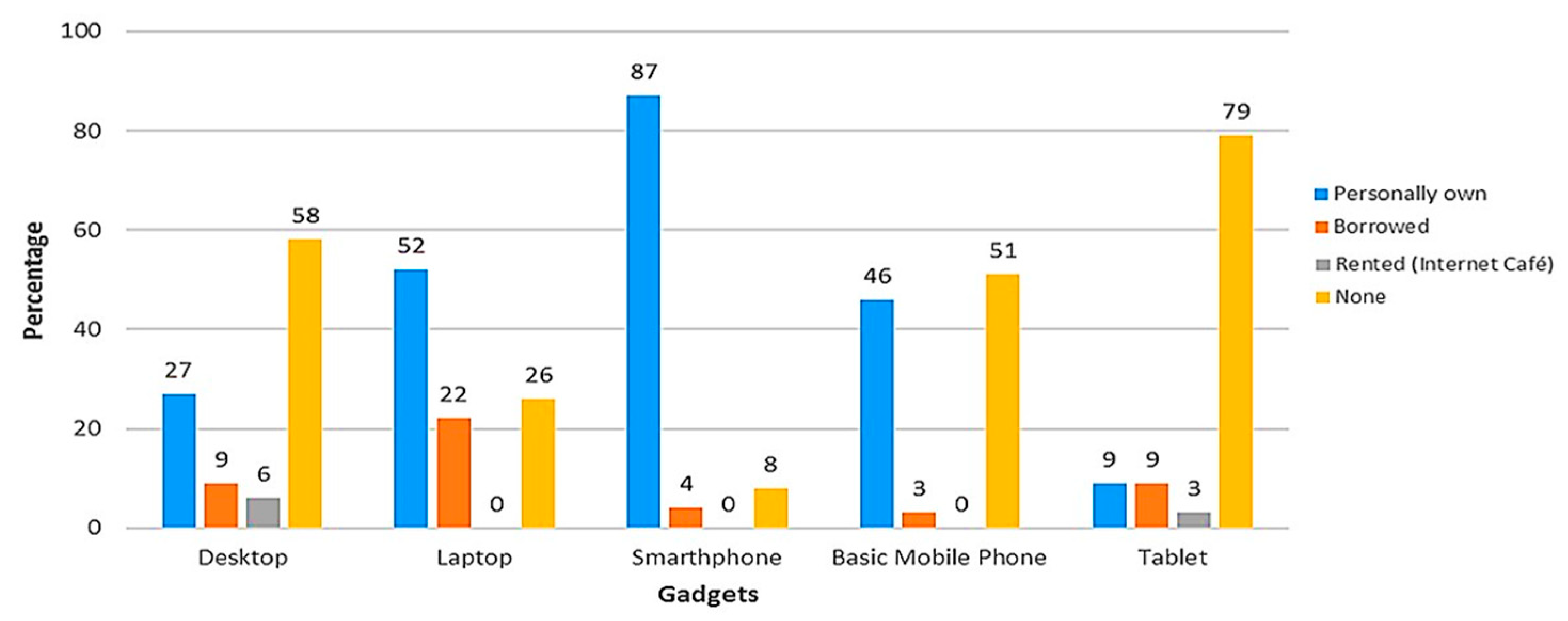

3.2. Gadgets for Online Learning

Figure 2 illustrates the gadgets used for online learning by the respondents. The figure reflects that most of the student respondents’ personally owned gadgets are smartphones (87%). Other respondents personally own a desktop (27%), laptop (52%), basic mobile phone (46%), and tablet (9%). Meanwhile, others borrow only their gadgets: desktop (9%), laptop (21%), basic mobile phone (3%), and tablet (9%). While very few rent desktops (6%) and tablets (3%) at internet café due to the restrictions due to the pandemic, 79% do not own tablets, 58% have no desktop, 51% have no basic mobile phone, and 8% have no smartphone.

3.3. Online Learning Tools

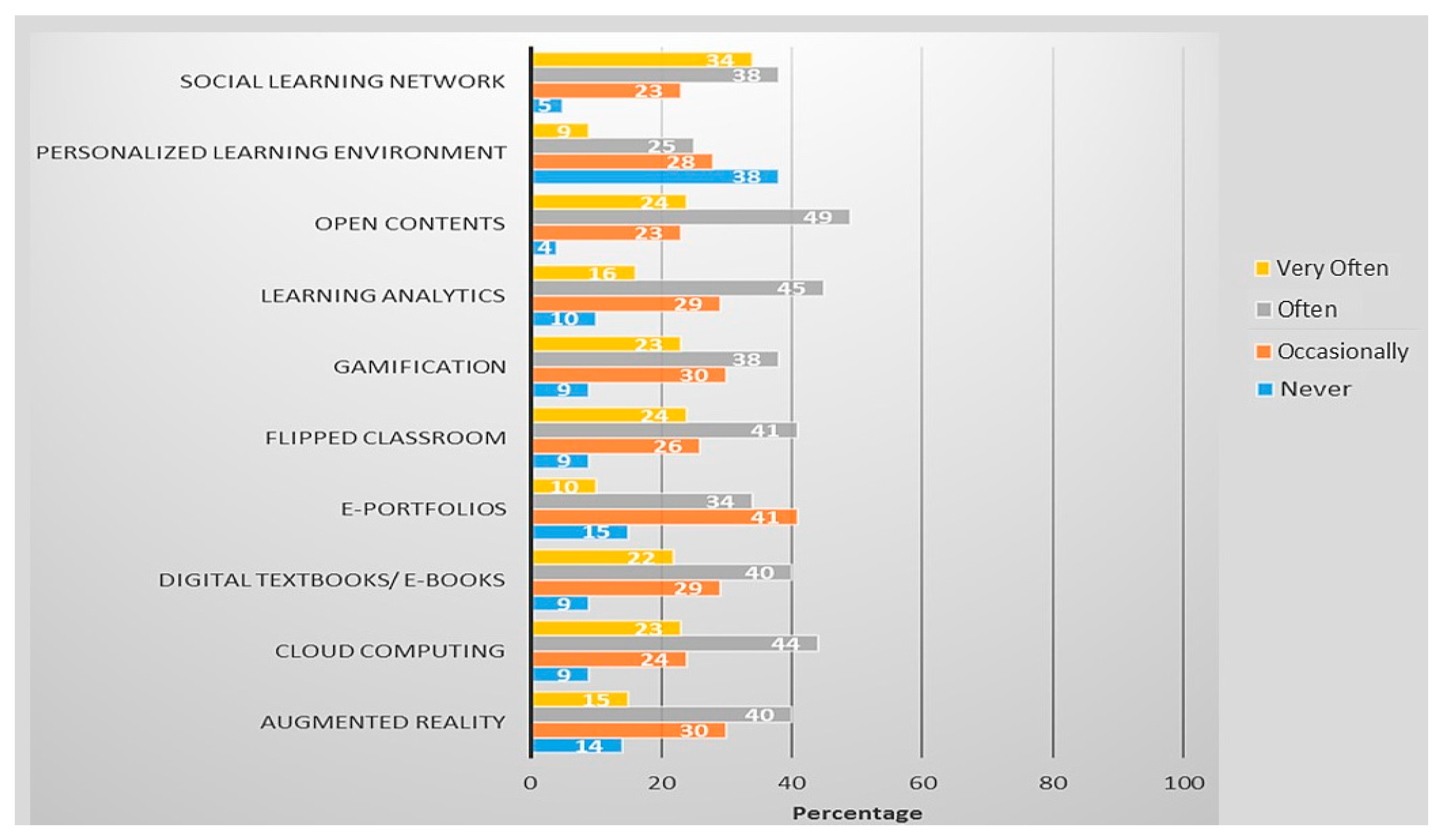

Shown in

Figure 3 is the frequency of using online learning tools. As reflected in the figure, student respondents often use social learning networks (SLNs) in their online learning with 34% response rate under “very often”. In addition, they often visit available content. Furthermore, e-portfolios are only used occasionally with 41% response rate despite their benefits in monitoring students’ progress in learning. Moreover, most respondents claimed they never use personalized learning environments (PLEs) with 38% response rate.

3.4. Online Learning Characteristics

3.4.1. Online Student Engagement

Table 2 displays the student respondents perceived OSE. Such was substantiated by the mean scores ranging from M=3.27 (SD=1.11) to M=4.17 (SD=0.85). Specifically, student respondents are into

“helping fellow students” (M=4.17, SD=0.85). However, they are not into

“posting in the discussion forum regularly” which garnered a relatively lower mean (M=3.27, SD=1.11). Also, they testified that being engaged in online learning they are

“putting put effort”, “listening/reading carefully”, and into

“getting good grade” with response rate M=4.05 (SD=0.80), M=4.10 (SD=0.78), and M=4.05 (SD=0.80), respectively, under characteristics of me. Noteworthy, the overall mean (M=3.85, SD=0.90) clearly shows that student respondents labeled themselves as moderately engaged in online learning.

3.4.2. Self-Regulated Learning

Shown in

Table 3 is the student respondents perceived self-regulated online learning. Based on the table, there are five (5) characteristic of self-regulated online learning namely metacognition, time management, environment structuring, persistence, and help-seeking. Firstly, the indicators

“I think of alternative ways to solve a problem and choose the best one for this online course” and

“I periodically review to help me understand important relationships in this online course” gained the highest response (M=4.08, SD=0.75) and lowest response (M=3.71, SD=0.89), respectively, under metacognition. Secondly, the indicator

“I often find that I don’t spend very much time on this online course because of other activities” has a relatively lower mean (M=3.68, SD=1.00) compared to the other two indicators with a similar response rate under time management. Next, the indicators

“I choose the location where I study for this online course to avoid too much distraction” and

“I know what the instructor expects me to learn in this online course” gained the highest response (M=4.03, SD=0.98) and lowest response (M=3.79, 0.84), respectively, under environmental structuring. Moving on, the indicators

“I work hard to do well in this online course even if I don’t like what I have to do” and

“When I am feeling bored studying for this online course, I force myself to pay attention” garnered the highest response (M=3.95, SD=0.89) and lowest response (M=3.63, SD=1.05), respectively, under persistence. Finally, the indicators

“When I do not fully understand something, I ask other course members in this online course for ideas” and

“I am persistent in getting help from the instructor of this online course” garnered the highest response (M=3.98, SD=0.95) and lowest response (M=3.50, SD=1.09), respectively, under help seeking. Significantly, the overall mean score (M=3.86, SD=0.92) indicates that student respondents are moderately self-regulated online learners.

3.4.3. Online Learning Self-Efficacy

Table 4 shows the perceived online learning self-efficacy of the student-respondents. Notice that except for using online library resources, communicating effectively with instructors and focusing on school work when faced with destruction, student-respondents agree that they are self-efficient as far as the indicators of OLSE is concerned. Meanwhile, students are most efficient in using synchronous technology to communicate with others (such as Skype) (M=3.39, SD=0.64). However, there is a relatively lower mean scores for using library online resources (M=2.27, SD=0.94) and for communicating effectively with instructor via e-mail (M=2.98, 0.76).

3.4.1. Effects of the Demographic Profile on OSE, SROL, and OLSE

The multivariate tests reflected results with no evidence of a significant effect of any of the predictor (independent variables) given the Pillai’s Trace > 0.05. Finally, tests between-subject effects revealed that there was no significant effect among the independent groups or levels of that outcome, except for gender and OLSE interaction (p < 0.05). Thus, only in OLSE a significant difference was found in terms of gender.

4. Discussion

This study was conducted to primarily obtain a profile of science education students in higher education institutions in the Philippines to characterize their OSE, SROL, and OLSE. As regards their profile variables, an emphasis on internet access and studying at night are not surprising because students were on a study at home at their own pace due to the pandemic. Meanwhile, a good internet connection indicates a favorable status to use online resources for distance learning, especially in the new normal.

As to the gadgets they use for online learning, findings revealed that 87% of the students own a smartphone. The result is consistent with the previous study in the Philippines conducted by [

42], in which students claimed that 91% owned smartphones, although that case was for senior high school students from private schools in the Philippines. Therefore, course online designers should consider a virtual environment accessible through mobile devices, especially smartphones. In addition, results showed the students are into the use of social learning network, implying the critical role of SLNs in the new normal. With the widespread misinformation yet easily accessible resources and faster communication even without load like in Facebook Messenger, online learning policymakers and implementers should consider an appropriate and timely plan to teach students how to extract and validate the information access or transmitted via SLNs. Furthermore, students often visit available content. Therefore, it necessitates more accessibility to these learning references, so teachers should include open content in online instructions. However, they should do it cautiously by looking at the accuracy and currency of the references. Moreover, the higher response rate on never using PLEs is similar to the result found by [

42] among high school students in the Philippines. It is about time to consider introducing these tools to online students so we can fully discover how they can benefit them.

Looking at OSE, students are fond of helping their fellow. This means that online learners highly practiced collaboration among themselves. This result manifests active learning among online students. [

43] reported that students extended help to fellow students to make online learning less isolating. In doing so, they use social networking to communicate with each other and their teachers. Such a statement counters the findings of [

25], where students felt a sense of isolation, making them demotivated due to the lack of social interaction. Meanwhile, findings revealed a relatively lower response rate on regularly posting in the discussion forum, indicating that they may be hesitant to publicly express their thoughts or questions. Hence, teachers should also consider explaining to students the benefits of participating in public discussion forums by encouraging them to express their ideas and opinions openly. [

44] found online discussions and interactive assignments engaging, such as when thought-provoking questions that are relevant to real-world situations prompt students’ thinking or when they share diverse opinions and when asked to develop personal perspectives.

In terms of SROL, student respondents testified that self-regulated learning indicators are moderately true to true for them. Significantly, they think of alternative ways to solve problems encountered in online learning. Students are resourceful in solving their online learning problems. To address such problems, teachers could help students make contingency plans. They may also provide them with various online learning resources so the latter can prepare better and could predict what they might do if a particular problem arises during their learning encounter. However, there is a relatively lower mean score for persistence in getting help from online instructors. One reason could be their reluctance to consult their instructors. Some authors found that this help-seeking issue is related to disappointment in teachers because of their inflexibility in course requirements and their instructors’ passive role in online learning [

26]. Other authors stated that students also experienced help-seeking issues due to a lack of interaction and immediate feedback from instructors [

25,

45]. Therefore, the teacher should build a good rapport among their students so they will find it welcoming to get help from them. Students recognize the instructor’s effort in consistently assisting them to keep them engaged and to ensure participation in productive discussion, as well as the way their instructor encourages them to acknowledge the point of view of their peers [

46].

When it comes to their OLSE, findings revealed that students are most efficient in using synchronous communication tools. The result can be attributed to the rampant use of communication tools during the pandemic, particularly virtual meeting rooms such as Zoom and Google Meet. Unfortunately, students testified they are not that efficient in using their library’s online resources. This might be attributed to their access to open content easily available in Google, as revealed in their profiles. However, online instructors should also encourage students to access library resources as they are reliable and validated learning resources.

Noteworthy, the findings on multivariate tests showed no evidence of a significant effect on any of the predictors and researchers found no significant effect among the independent groups, except for gender and OLSE interaction. The result contradicts to the previous work of [

47] in which findings revealed no significant difference on the overall self-efficacy in terms of gender. One consideration for the contradicting results could be the difference in the number of study participants. [

47] included over nine thousand participants, while this study covered only over three hundred students. Another could be the context because this study involved Filipino students who are neophytes in online learning while those in literature are into compulsory courses delivered in distance learning. Thus, it may concern teachers’ attention to the different strategies used by different genders among Filipino students for their self-efficiency.

5. Conclusions, Implications and Recommendations

Based on the findings, the majority of the respondents are 18-22 years old (n=350, 94.09%), most are men (n=183, 49.19%), the majority has internet access via home broadband with a good signal (> n=147, 40%), the majority are from NCR (n=183, 49.19%), and most of them studies at night (n=173, 46.51%). In terms of online learning characteristics, results substantiated that the student respondents characterize themselves as moderately engaged in online learning (M=3.85, SD=0.90), they are moderately self-regulators in their online learning (M=3.86, SD=0.92,), and they agreed that the OLSE indicators are true of them (M=3.14, SD=0.73). Results imply that teachers may consider teaching strategies and provide specific instructions that will help students fully engage in online learning, have SRL skills and or employ strategies as their very characteristics, and become very self-efficient in online learning to prepare them when another exceptional time comes so quality and inclusive will continue. Finally, the findings on MANOVA showed that except for gender and online learning self-efficacy, there was no significant main effect among the independent groups (demographic profile) or levels of that outcome (OSE, SROL, and OLSE). Therefore, a significant difference exists in OLSE regarding gender and not the other profile variables. This implies that online instructors may be considerate when assigning assignments involving gender preferences of the students. In this way, gender-bias issues would be avoided.

The findings of this research contributes to the literature by providing the baseline data of the students’ profile as far as online learning is concerned, especially science education students’ engagement, self-regulation, and self-efficacy, thereby addressing this gap in literature. In addition, this study offers the readers, science education teachers, and higher education policy-makers in the Philippines a grasp of empirically-based information about how students manage their online learning given their accessible online learning tools. In this manner, decision-making for policy or curriculum revisions when considering flexible learning modalities such as online learning, designing an inclusive OLE, or providing an appropriate online learning materials for better student engagement and to support SROL and self-efficacy among higher education students who are highly expected of being autonomous and active learners.

As for the recommendations, the inclusion of Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) is highly recommended to determine whether the indicators of OSE, SRL, and OLSE can be considered latent variables of independent learning. In literature, what is available includes the use of SEM to investigate the relationship among the learning environment, self-regulate strategies, and pre-service science teachers’ beliefs on studying Physics [

48] and student-teachers’ self-efficacy on digital competency in a technology-rich classroom [

34]. Also, synchronous observation of classes may be done in future studies to verify student characteristics in the classroom. Lastly, students’ academic achievement may be considered in future studies to determine the existing relationship with OSE, SRL, and OLSE of online learners.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.B, D.D.E and M.P.; methodology, M.R.B and M.P.; software, M.R.B; validation, M.R.B, D.D.E and M.P.; formal analysis, M.R.B, D.D.E and M.P.; investigation, M.R.B.; resources, M.R.B and D.D.E.; data curation, M.R.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.B.; writing—review and editing, M.R.B, D.D.E and M.P.; visualization, M.R.B.; supervision, D.D.E and M.P..; project administration, M.R.B.; funding acquisition, M.R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to REASON that this survey research was conducted as part of coursework requirement which needs no clearance to be submitted to the Research Ethics Office of the university.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The researchers will provide the data upon reasonable request. Data are not publicly available due to confidentiality issues.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend heartfelt thanks to all the student-respondents to voluntarily participated in this study. Also, the corresponding author extends her profound gratitude to the Department of Science and Technology- Science Education Institute (DOST-SEI) for the scholarship grant that served as an enabling support for her enrollment in the Ph.D. program at her graduate school.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pangeni, S. K. Open and distance learning: Cultural practices in Nepal. Eur. J. Open Distance E-Learn. 2016, 19(2), 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, N.; Khan, N. H. Online teaching-learning during Covid-19 pandemic: Students’ perspective. Online J. Distance Educ. E-Learn. 2020, 8(4), 202–213. Available online: http://tojdel.net/journals/tojdel/articles/v08i04/v08i04-03.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Susila, H. R.; Qosim, A.; Rositasari, T. Students’ perception of online learning in covid-19 pandemic: A preparation for developing a strategy for learning from home. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 8(11), 6042–6047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutarto, S.; Sari, D. P.; Fathurrochman, I. Teacher strategies in online learning to increase students’ interest in learning during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Konseling Dan Pendidik. JKP. 2020, 8(3), 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizun, M.; Strzelecki, A. Students’ acceptance of the COVID-19 impact on shifting higher education to distance learning in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2020, 17(18), 6468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapanta, C.; Botturi, L.; Goodyear, P.; Guàrdia, L.; Koole, M. Online university teaching during and after the Covid-19 crisis: Refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 2020, 2, 923–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A.; Chen, X. Online education and its effective practice: A research review. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2016, 15, 157–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, H.; Almeida, F.; Figueiredo, V.; Lopes, S. L. Tracking e-learning through published papers: A systematic review. Comput. Educ. 2019, 136, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, J. S.; Rockinson-Szapkiw, A. J.; Dubay, C. Persistence model of non-traditional online learners: Self-efficacy, self-regulation, and self-direction. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2020, 34(4), 306–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Khalil, V.; Helou, S.; Khalifé, E.; Chen, M. A.; Majumdar, R.; Ogata, H. Emergency online learning in low-resource settings: Effective student engagement strategies. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churiyah, M.; Sholikhan, S.; Filianti, F.; Sakdiyyah, D. A. Indonesia education readiness conducting distance learning in Covid-19 pandemic situation. Int. J. Multicult. Multireligious Underst. 2020, 7(6), 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, M. S.; Rynearson, K.; Kerr, M. C. Student characteristics for online learning success. Internet High. Educ. 2006, 9(2), 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trowler, V. Student engagement literature review. High. Educ. Acad. 2010, 11(1), 1–15. Available online: https://pure.hud.ac.uk/en/publications/student-engagement-literature-review (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- Pittaway, S. M. Student and staff engagement: Developing an engagement framework in a faculty of education. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 37(4), 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K. A. Student engagement in online learning: What works and why. ASHE High. Educ. Rep. 2014, 40(6), 1–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolliger, D. U.; Martin, F. Instructor and student perceptions of online student engagement strategies. Distance Educ. 2018, 39(4), 568–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, T.; Douglas, T.; Trimble, A. Facilitation strategies for enhancing the learning and engagement of online students. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2020, 17(3), 8. Available online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/jutlp/vol17/iss3/8 (accessed on 20 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Douglas, T.; James, A.; Earwaker, L.; Mather, C.; Murray, S. Online discussion boards: Improving practice and student engagement by harnessing facilitator perceptions. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2020, 17(3), 7. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1264456.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- SOLAS, E. C.; Wilson, K. Lessons learned and strategies used while teaching core-curriculum science courses to english language learners at a Middle Eastern university. J. Turk. Sci. Educ. 2015, 12(2), 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderibigbe, S. A. Online discussions as an intervention for strengthening students’ engagement in general education. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6(4), 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malan, M. Student engagement in a fully online accounting module: An action research study. South Afr. J. High. Educ. 2020, 34(4), 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panadero, E.; Alonso-Tapia, J. How do students self-regulate? Review of Zimmerman’s cyclical model of self-regulated learning. An. Psicol. 2014, 30(2), 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard-Brak, L.; Paton, V. O.; Lan, W. Y. Profiles in self-regulated learning in the online learning environment. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2010, 11(1), 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Wang, Q.; Xu, J.; Zhou, L. Effectiveness of students’ self-regulated learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Insigt. 2020, 34(1), 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biwer, F.; Wiradhany, W.; Oude Egbrink, M.; Hospers, H.; Wasenitz, S.; Jansen, W.; De Bruin, A. Changes and adaptations: How university students self-regulate their online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 642593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensley, L. C.; Iaconelli, R.; Wolters, C. A. “This weird time we’re in”: How a sudden change to remote education impacted college students’ self-regulated learning. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2022, 54(sup1), S203–S218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J. A.; Plumley, R. D.; Urban, C. J.; Bernacki, M. L.; Gates, K. M.; Hogan, K. A.; Demetriou, C.; Panter, A. T. Modeling temporal self-regulatory processing in a higher education biology course. Learn. Instr. 2021, 72, 101201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizah, U.; Nasrudin, H. Metacognitive skills and self-regulated learning in pre-service teachers: Role of metacognitive-based teaching materials. J. Turk. Sci. Educ. 2021, 18(3), 461–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejubovic, A.; Puška, A. Impact of self-regulated learning on academic performance and satisfaction of students in the online environment. Knowl. Manag. E-Learn. 2019, 11(3), 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sletten, S. R. Investigating flipped learning: student self-regulated learning, perceptions, and achievement in an introductory biology course. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2017, 26, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.-H.; Kim, B. J. Students’ self-regulation for interaction with others in online learning environments. Internet High. Educ. 2013, 17, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aşkar, P.; Umay, A. Perceived computer self-efficacy of the students in the elementary mathematics teaching programme. Hacet. Univ. J. Educ. 2001, 21(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B. J. Self-efficacy and educational development. Self-Effic. Chang. Soc. 1995, 1(1), 202–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elstad, E.; Christophersen, K.-A. Perceptions of digital competency among student teachers: Contributing to the development of student teachers’ instructional self-Efficacy in technology-rich classrooms. Educ. Sci. 2017, 7(1), 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Watson, S. L.; Watson, W. R. The relationships between self-Efficacy, task value, and self-regulated learning strategies in massive open online courses. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2020, 21(1), 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robledo, D. A.; Miguel, F.; Arizala-Pillar, G.; Errabo, D. D.; Cajimat, R.; Prudente, M.; Aguja, S. Students’ knowledge gains, self-efficacy, perceived level of engagement, and perceptions with regard to home-based biology rxperiments (HBEs). J. Turk. Sci. Educ. 2023, 20(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, H. G. Ex Post Facto Studies as a Research Method. Special Report No. 7320. 1973. ERIC. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED090962.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Dixson, M. D. Measuring student engagement in the online course: The online student engagement scale (OSE). Online Learn. 2015, 19(4), n4. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1079585.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2021). [CrossRef]

- Jansen, R. S.; Van Leeuwen, A.; Janssen, J.; Kester, L.; Kalz, M. Validation of the self-regulated online learning questionnaire. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2017, 29(1), 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, W. A.; Kulikowich, J. M. Online learning self-efficacy in students with and without online learning experience. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2016, 30(3), 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, W., Pugliese A., & Recker, J. Introduction. Qualitative Data Analysis. Springer, Cham, 2017; p. 1.

- Jin, W.; Prudente, M. S.; Aguja, S. E. Students’ experiences and perceptions on the use of mobile devices for learning. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2018, 24(11), 8507–8510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, M.; Plough, C. Helping to make online learning less isolating. TechTrends 2009, 53(4), 57. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/download/79948695/Barbour2009.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Buelow, J. R.; Barry, T.; Rich, L. E. Supporting learning engagement with online students. Online Learn. 2018, 22(4), 313–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruso, J.; Stefaniak, J.; Bol, L. An examination of personality traits as a predictor of the use of self-regulated learning strategies and considerations for online instruction. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2020, 68, 2659–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones, M. R. B, & Errabo, D. D. R. Student’s voice of e-learning: implication to online teaching practice. In 2021 3rd International Conference on Modern Educational Technology (ICMET 2021), Jakarta, Indonesia, 21-23 May, 2021; Association of Computing Machinery New York, NY, USA. [CrossRef]

- Yavuzalp, N.; Bahcivan, E. The online learning self-efficacy scale: Its adaptation into Turkish and interpretation according to various variables. Turk. Online J. Distance Educ. 2020, 21(1), 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanti; Maison; Mukminin, A.; Syahria; Habibi, A.; Syamsurizal. Exploring the relationship between preservice science teachers’ beliefs and self-regulated strategies of studying physics: A structural equation model. J. Turk. Sci. Educ. 2018, 15(4), 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).