1. Introduction

Due to early initiation and increased effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy (ART), people living with HIV (PLHIV) had prolonged lifespan, thus, increased in population [

1]. Adherence to ART reduces morbidity and mortality by suppression of viral replication, restoration and preservation of immune function, and prevention of drug resistance [

2]. Before the pandemic, the crude death rate of patients on antiretroviral therapy was 12.2 deaths per 100 patient-years, with a rate of 42.5 deaths per 100 patient-years for non-adherent patients and 6.1 deaths per 100 patient-years for adherent patients. Poor adherence with ART may result in treatment failure and death [

3].

HIV continues to be a major public health issue globally with an estimated 37.7 million people living with HIV (PLHIV) in 2020 [

4]. According to The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), PLHIV experience more severe outcomes and have higher comorbidities from COVID-19 than people not living with HIV [

5]. Countries worldwide have implemented COVID-19 “lockdown” measures to minimize physical contact between individuals and stay indoors [

6]. However, these measures have a negative impact in HIV treatment services, access to treatment, and adherence [

7]. The Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria reported that, according to data collected at 502 health facilities in 32 African and Asian countries, HIV testing declined by 41% and referrals for diagnosis and treatment declined by 37% during the first COVID-19 lockdowns in 2020, compared with the same period in 2019. These socially-produced burdens can affect the physical, emotional, and social well-being of PLHIV in this time of pandemic [8-9].

Moreover, mortality rate among the COVID-19 patients with HIV infection is higher than, those COVID-19 patients without HIV infection [10-11]. This in turn led to determination of barriers to medication adherence in PLHIV at the time of COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines and its correlation with sociodemographic characteristics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aims

a. Transportation and Delivery

b. Location and Treatment Hubs

c. Checkpoints and Crossing Borders

d. Stock of ARVs and other medicines

e. Financial assistance

f. Psychosocial support

g. Verification (including ARV booklets)

h. Temporary shelter and housing

- 2.

Is there any significant association between the following HIV treatment barriers and socio-demographic characteristics?

a. Location of treatment hubs and respondents who finished college/graduate studies

b. Checkpoints and crossing borders and:

i. Respondents from Northern Luzon Region

ii. Unemployed respondents

c. Financial assistance and:

i. Respondents 18 to 25 years old

ii. Unemployed respondents

iii. Respondents who finished elementary/high school

d. Psychosocial support and:

i. Respondents from NCR

ii. Respondents 26 to 30 years old

e. Stocks of ARVs and other medicines and employed respondents

2.2. Study Design

A cross-sectional study was done by using survey questionnaire (

Appendix A) which was distributed via online social media (Twitter). The questionnaire was divided into five parts. The first part consisting of an introduction regarding the purpose of the research. The second part includes the respondents’ consent to voluntarily participate in the research. The third part of the questionnaire includes the unique identification code of each respondent which was patterned in RITM when enrolling HIV patients for ARV treatment.

The fourth part of the questionnaire is the demographic questions which include the age, region of residence, gender identity, sexual orientation, educational background and employment status were self-reported by all included participants. The fifth part of the questionnaire consists of one close ended question on issues encountered by the respondent in accessing antiretroviral therapy, in the time of COVID-19, and two open ended questions where the respondent can provide more details regarding the issues they identified in the previous question and other HIV-related concerns that they have. Specifically, these are the questions asked: (1) “What issues did/do you encounter in accessing HIV treatment and care services, including antiretroviral therapy, in the time of COVID-19? Check all that apply.”; (2) “Please provide more details regarding the issues you identified in the previous question.”; and (3) “You may also share other HIV-related concerns that you currently have.”

The questionnaire has been validated by UNDP and UNAIDS and was used by Engr. Xavier Javines Bilon in his published report entitled: Leaving No One Behind: Treatment and Care Concerns of People Living with HIV in the Time of COVID-19 - A Philippine Situationer [

12].

2.3. Limitations of the Study

All participants in the inclusion criteria are Filipino, 18 years old and above and a confirmed case of HIV on ART. The limitation of this study in the aspect of data gathering is mainly due to the reason of COVID-19 pandemic in which close physical contact is still prohibited and is needed in order to maintain the social distancing policy to avoid the rapid increase of cases, especially with the immunocompromised respondents. With that, data collection was only conducted through the use of online questionnaire distributed via Twitter [

13].

2.4. Sample Size Computation

The survey questionnaire accepted responses from November 26, 2021 to January 10, 2022. We received 118 responses with 2 duplicates. After processing, we have a non-probability sample of 116 valid responses (n = 116). The computed sample size was 82 using Open Epi software (Dean et al, 2013). The following assumptions were used:

- -

95% confidence level

- -

Expected % of barriers (UNDP and UNAIDS, 2021)

- o

59% - location of treatment hubs

- o

57% - checkpoints and crossing borders

- o

54% - stock of ARVS

- -

20% of estimate relative precision

| Barriers |

% |

+/- absolute precision(20% of estimate)

|

n |

| Transportation and delivery |

67% |

1.3 |

1,419 |

| Location of treatment hubs |

59% |

11.8 |

67 |

| Checkpoints and crossing borders |

57% |

11.4 |

73 |

| Stock of ARVs |

54% |

10.8 |

82 |

| Financial assistance |

41% |

8.2 |

139 |

| Psychosocial support |

20% |

4.0 |

384 |

| Temporary shelter and housing |

4% |

0.8 |

2,300 |

| OFW concerns |

3% |

0.6 |

3,096 |

2.5. Data Analysis

Data was analyzed using Stata software. Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages, quantitative data was summarized using mean and standard deviation. Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, whichever is more appropriate, was used to determine association between socio-demographic characteristics and HIV treatment barriers.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic characteristics

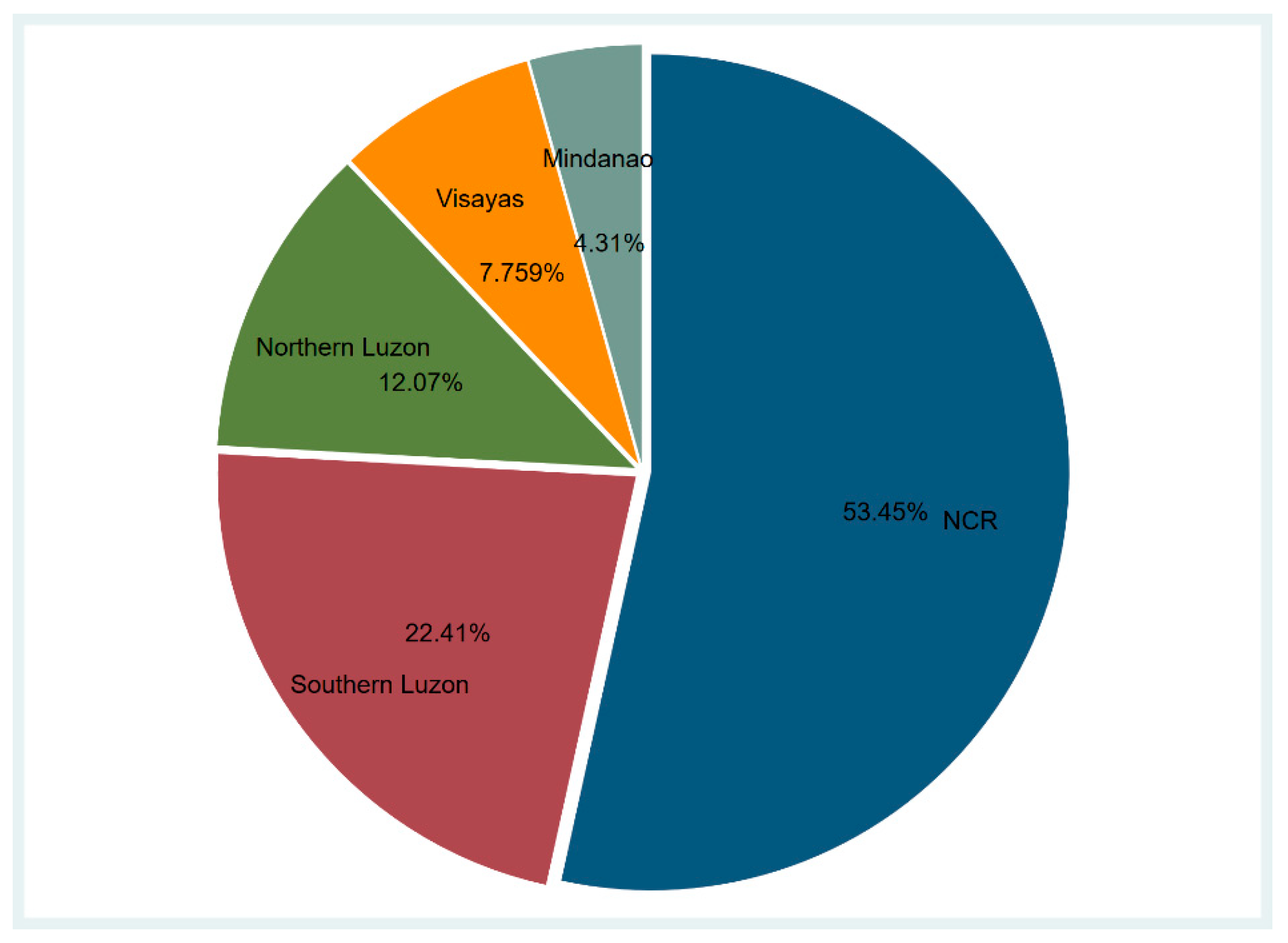

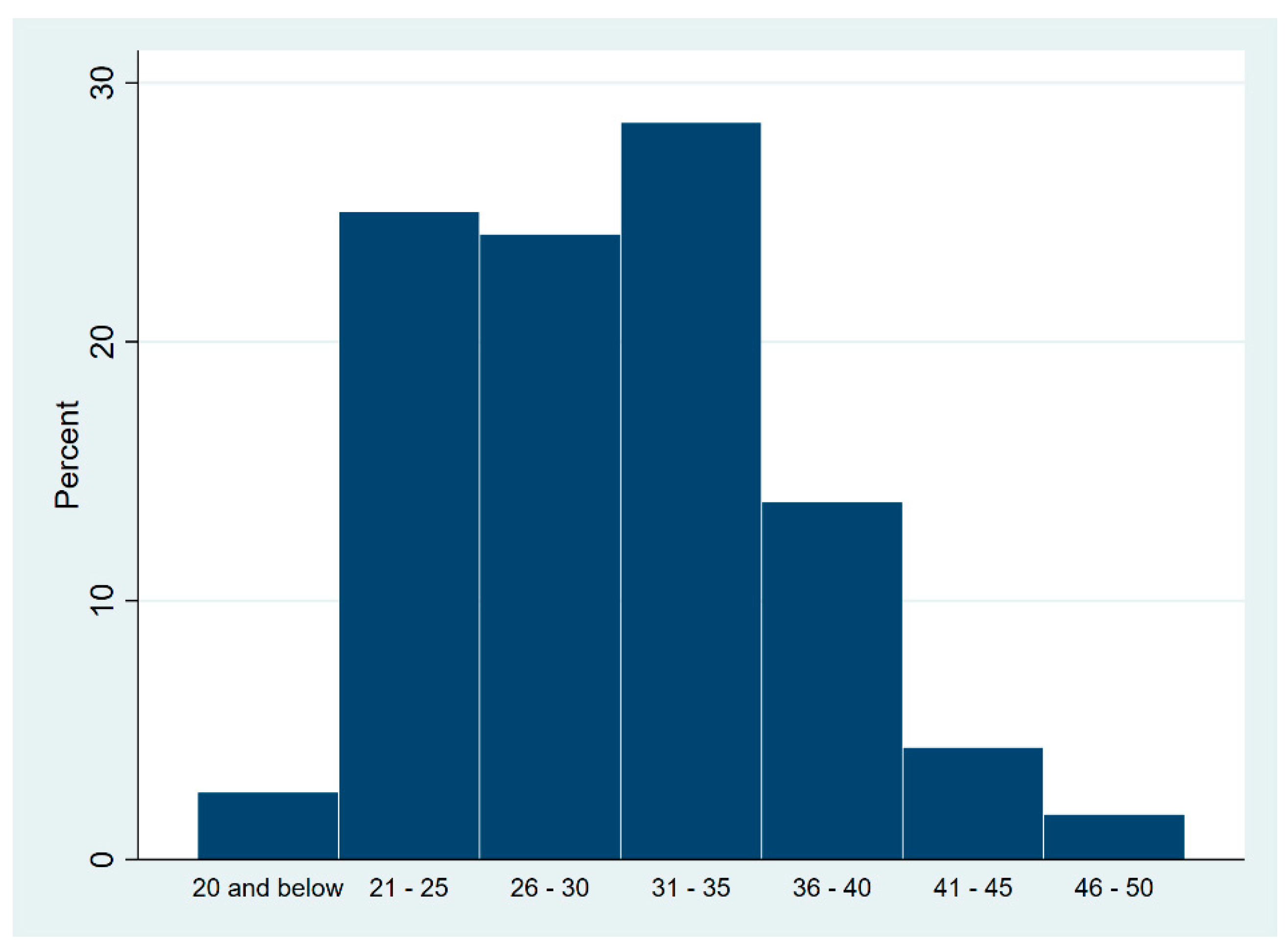

A total of 116 respondents answered the online survey. Majority (53.4%) were from NCR, 34.5% from northern and southern Luzon, and 12.1% from Visayas and Mindanao (

Table 2 and

Figure 1). Study participants were 18 to 50 years old (

Figure 2) with mean age of 30.25 years old (SD = 6.22) and 91.3% were 21 to 40 years old. Respondents were mostly males (95.7%), were either homosexual (59.5%) or bisexual (37.9%), had college or graduate degrees (87.1%) and were employed (70.7%).

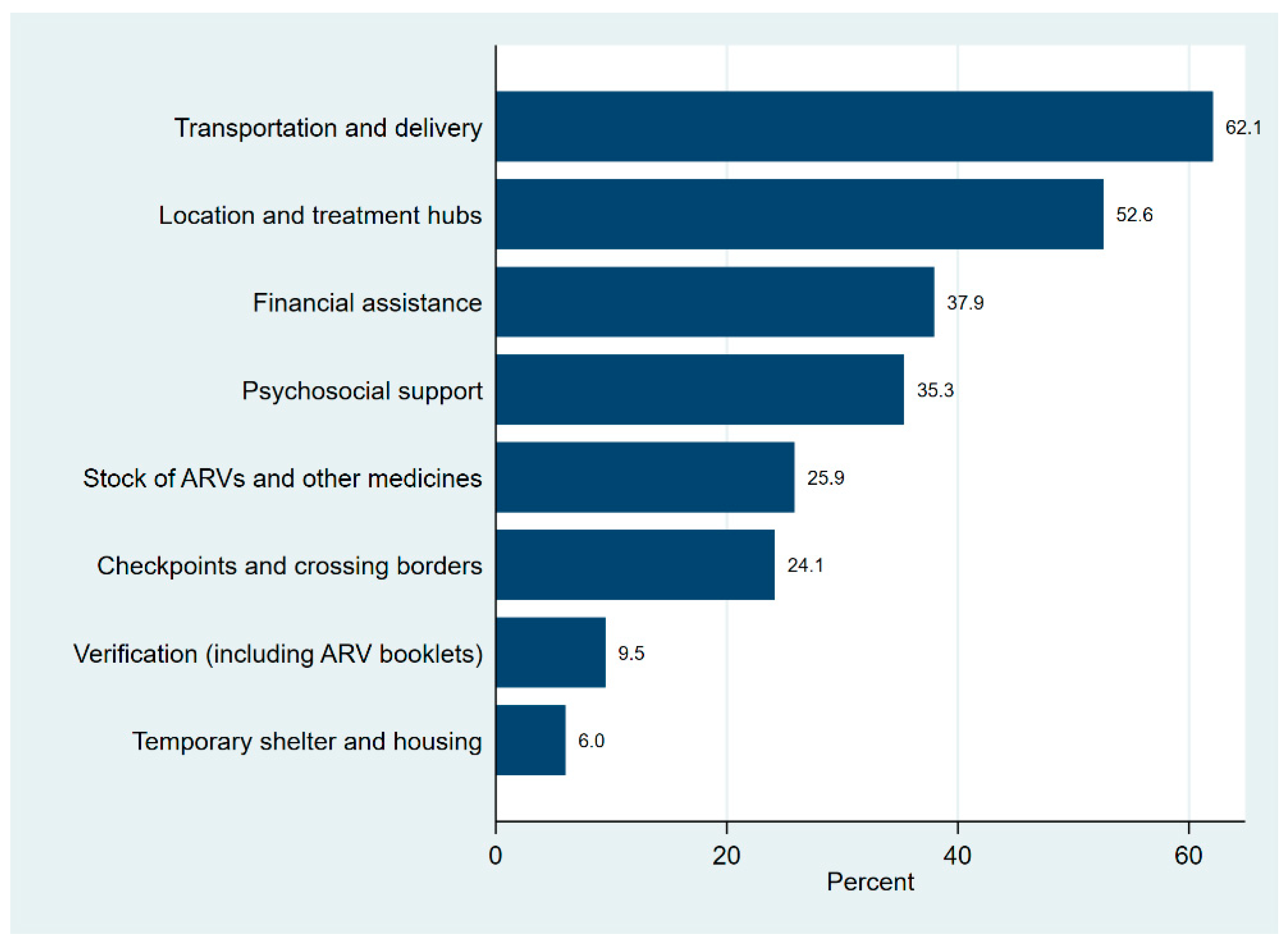

3.2. Identified HIV treatment barriers

The most common HIV treatment barriers reported by respondents in accessing treatment and care were unavailability of transportation and cost of courier services for ARV delivery (62.1%), location of treatment hubs (52.6%) and financial assistance (37.9%). The least frequent barriers to HIV treatment were temporary shelter and housing (6%) and verification including ARV booklets (9.5%). Around 40% of the respondents reported to having 3 or more issues on HIV treatment and two respondents, both from NCR, were experiencing all 8 issues (

Table 3 and

Figure 3).

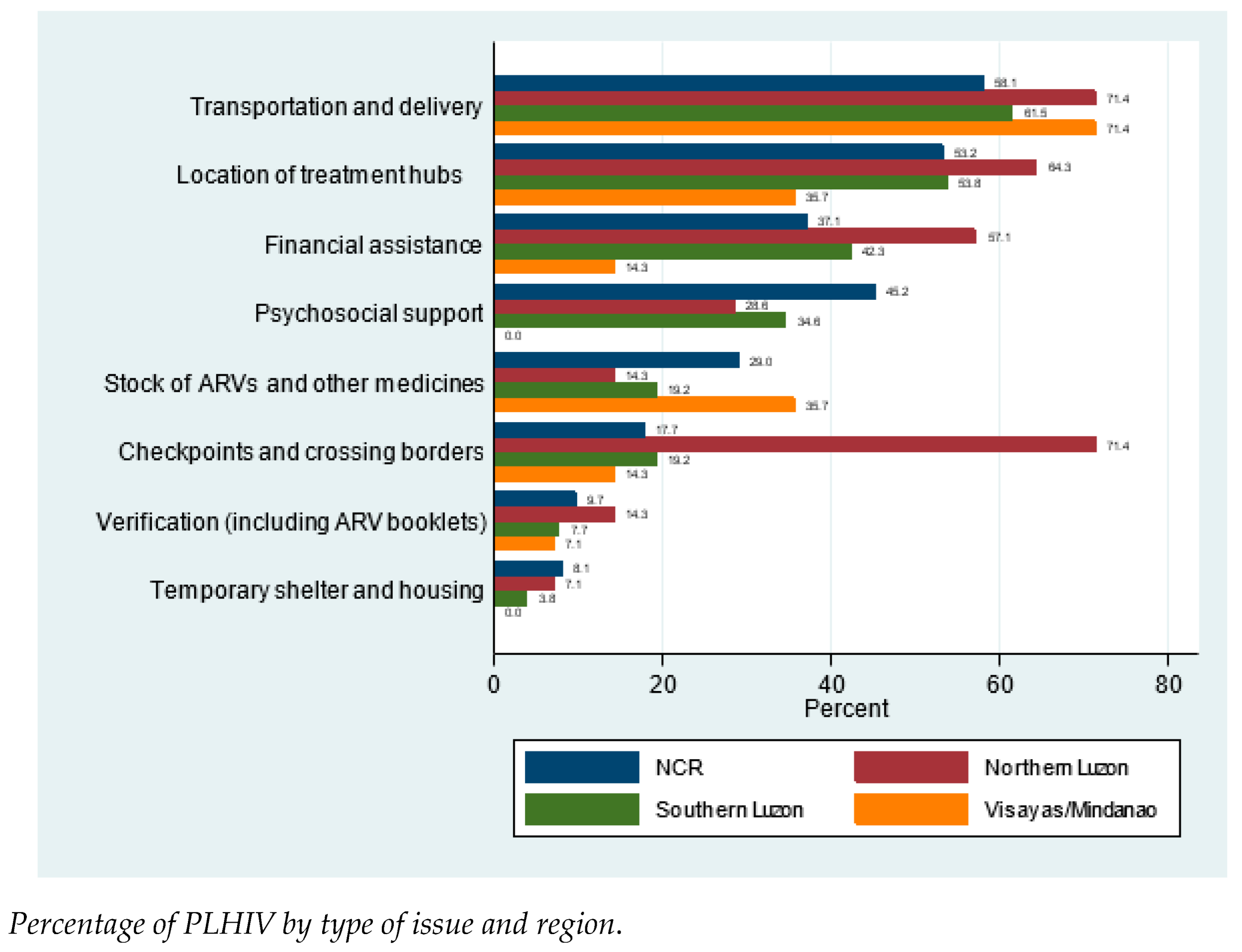

3.3. HIV treatment barriers and respondents by region

Tests for association showed that that there were significant association between region and checkpoints and crossing borders, and psychosocial support (

Table 4 and

Appendix B). Issues on checkpoints and crossing borders was significantly higher in Northern Luzon (71.4%) than other (17.7%) regions (p < 0.001). On the other hand, issues on psychosocial support were significantly higher (p = 0.018) in NCR (45.2%) compared to other regions (24.1%).

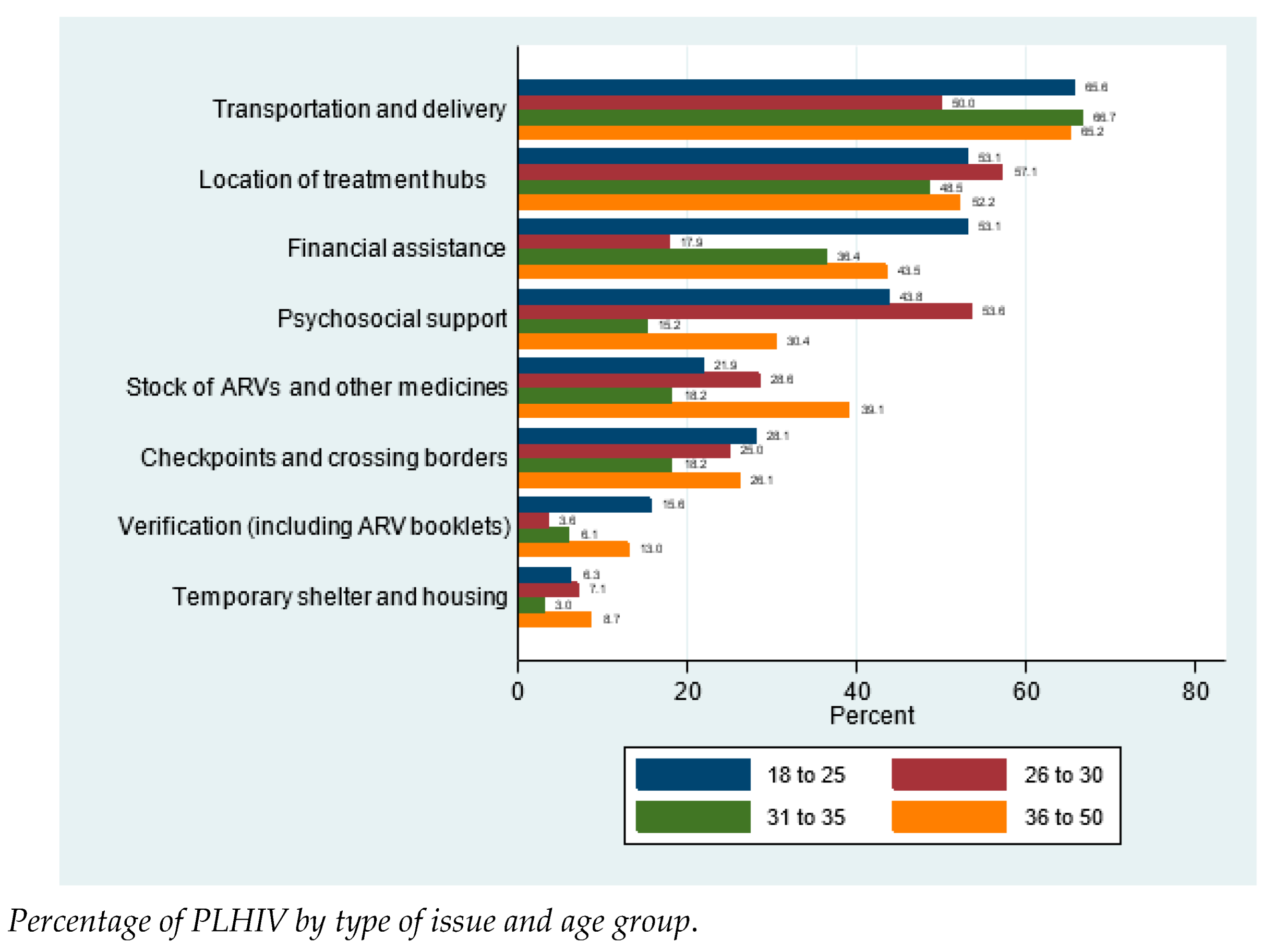

3.4. HIV treatment barriers and respondents by age group

There were significant association between age group and financial assistance and psychosocial support (

Table 5 and

Appendix C). Issues on financial assistance was highest in 18 to 25 years old (53.1%) and then 36 to 50 years old (43.5%) and was lowest (17.9%) in 26 to 30 years old. Though lowest in financial assistance issue, respondents 26 to 30 years old had the most having issues on psychosocial support (53.6%).

3.5. HIV treatment barriers and respondents by educational status

Educational status was significantly associated with issues on financial assistance, and location of treatment hubs (

Table 6 and

Appendix D). Those who finished elementary or high school (66.7%) had significantly higher (p=0.014) issues on financial assistance than those who finished college or graduate studies (33.7%). On the contrary, issues on location of treatment hubs were significantly higher (p = 0.031) among those who finished college or graduate studies (56.4%) compared to elementary or high school graduates (26.7%).

3.6. HIV treatment barriers and respondents by employment status

Employment status was significantly associated with having issues on checkpoints and crossing border, financial assistance, and stock of ARVs and other medicines (

Table 7 and

Appendix D). Those who were unemployed had significantly higher issues on checkpoints and crossing borders (41.2%) and financial assistance (70.6%) compare to those employed (17.1% and 24.4%, respectively). However, stocks of ARVs and other medicines were more problematic (p-0.007) among those who were employed (32.9%) than those unemployed (8.8%).

4. Discussion

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 has rapidly emerged as the causative agent of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, causing significant threat to public health, particularly among the vulnerable populations, including the elderly and those of any age with underlying chronic medical conditions and people with compromised immune system [

14].

PLHIV and the elderly were highlighted by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as a population that may be at a higher risk for severe impact of COVID-19 compared to the general population, which is based on potential interactions between COVID-19, HIV, and other risk factors for complications of COVID-19 such as diabetes and hypertension that are common in PLHIV, potential implications with care and treatments, and high rates of socially-produced burdens in the form of violence, stigma, discrimination, isolation, and hate experienced by PLHIV [

15].

PLHIV have a high probability of experiencing treatment interruptions due to restrictions on non-emergency medical appointments related to social distancing COVID-19 protocol. In turn, those who are not taking ART or whose disease is not well managed may be at increased risk of acquiring COVID-19 due to compromised immune system leading to serious symptoms and death [

16].

In this study, the respondents reported that the top three issues encountered in the Philippines during the time of COVID-19 pandemic were transportation and delivery, location and treatment hubs, and financial assistance. The lack of public transportation within a city/municipality, across cities in Metro Manila, and going in and out of Metro Manila, is the major concern of respondents with an estimate of 62%, which includes those who need to go to their treatment hub for consultation and/or ARV refill. Some of the respondents had to walk from their home to the HIV facility. A respondent from Luzon said verbatim, “When the pandemic first happened, I need to walk from my residence in Pasay Rotonda to Makati Medical Center”. One of 9 respondents from Visayas commented verbatim “Access to transportation and the location of my hub is a bit far from where I lived.” While in Mindanao, 1 of 4 respondents commented verbatim “I do live miles away from my hub, need to travel every refill.”

Approximately 53% of respondents have issues with the location of treatment hub from their residence, specifically for those who need ARV refills. Some people living with HIV in Metro Manila opt to use courier services such as Grab or Lala Move. Respondents either experience missed doses of daily ARV due to delay of delivery, ARV refill were delivered in a wrong address, address is out of coverage for the courier or difficulty contacting their treatment hub to inquire if there is option of ARV delivery. This is worsened by those who also experienced financial constraints with the delivery fee. In addition, some treatment hubs do not allow the delivery of ARV and require them to personally claim it in the clinic.

For others who live outside Metro Manila, the nearest HIV facility may be too far. One of the respondents asked his father who knows how to ride a bike to get ARV refill in his behalf. Some people living with HIV opt to use courier services but the address is out of coverage. There are also areas in which there are no accessible HIV facility by foot nearby such as Palawan.

In Mindanao, the situation is worse. One of the respondents had his ARV refill by having it delivered by a provincial bus in route to his location. Some respondents had to transfer to another place of residence nearer to their treatment facility.

Table 8 shows the top five farthest respondents living with HIV from an HIV facility.

Many PLHIV in low- and middle-income countries experience reduced income, consequently leading to loss to follow-up and despite anti-retroviral (ARV) medicine being free, they still need to pay for registration, laboratory and transportation, thus lost-to-follow-up in order to avoid this cost [

17]. In the Philippines, roughly 38% of respondents have issues with financial assistance. For Filipinos living with HIV who already experience discrimination and other employment barriers before the pandemic, it is much more perilous in the current economic situation. According to the Labor Force Survey of the Philippine Statistics Authority, around 9.1 million Filipinos lost their jobs during the pandemic. In 2021, unemployment rate was highest during the month of September at 8.9%. Many are affected by companies employing a “no work, no pay” policy, leaving them without enough income to cover for their expenses, including those for their HIV treatment.

During the time of community quarantine, around 35% of respondents reported that they experienced anxiety and depression with no psychosocial support available, since social gatherings or meetings are not allowed. Some people living with HIV noted that it felt something is still lacking despite the support they receive from their family. Meanwhile, some respondents look for empathy from other people living with HIV who also face the same battle with them. Fear and anxiety related to transmission are the common denominators of HIV and COVID-19. This pandemic caused PLHIV with a high stress level because of the possibility of acquiring another virus that could kill them, in addition to the fact that there is physical distancing or social isolation recommended by the CDC to reduce the spread of COVID-19, the lack of knowledge of how SARS-CoV-2 may synergize with HIV and the absence of scientifically proven treatments to address symptoms and prevent death [18-21]. The pandemic fear in general can cause or worsen existing mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, and substance abuse, especially among the elderly with HIV. Older PLHIV confront myriad of mental health issues such as depression, stigma and ageism [22-26]. Social distancing and lockdown in many countries create a huge psychological impact undermining the overall well-being of these individuals, losing hope of improving their health outcomes and consequently leading to decrease in adherence to ART [27-32].

The analysis carried out by the UNAID on the potential impact of COVID-19 pandemic in low- and middle-income countries around the world on the supplies of generic ARV medicines used to treat HIV showed that the lockdown and border closures imposed to control the spread of COVID-19, is significantly affecting the production of these medicines and as such could potentially lead to increase in the cost and shortage in the supply of these drugs. The decrease in quantity of ARV medicines across borders is due to combined result of shortages of workforces in manufacturing facilities due to physical distancing and lockdown and restriction of sea and air transport dents the manufacture and distribution of raw materials and other products such as packaging materials pharmaceutical companies needs to in order to manufacture these medicines [

33].

An estimate of 26% of respondents reported unavailability or limited availability of certain ARV drugs and other medicines in their respective treatment hubs within and outside Metro Manila. These drugs include cotrimoxazole, azithromycin, isoniazid, and nevirapine. Several respondents experience partial refills wherein they were provided as low as 15 tablets to one or two bottles, instead of the usual three bottles. One respondent had to shift to another combination of ARV drugs because of unavailability, shifting from lamivudine/nevirapine to tenofovir/lamivudine/dolutegravir. One respondent had difficulty with ARV refill since his treatment hub is not operating during weekends due to pandemic while one respondent reported that the treatment hub provides expired ARV drugs. Meanwhile, one respondent experienced being charged for prophylaxis medications which was previously free and comes in package with his ARV. The treatment hub informed him that these was due to shortage of budget of the treatment facility. These issues are compounded by other issues such as those with transportation, location of HIV facilities, checkpoints and crossing borders, and financial assistance, making HIV treatment and care services more inaccessible to people living with HIV in the time of COVID-19 pandemic.

Approximately 24% of respondents have to go to a neighboring city/municipality to go to the nearest HIV facility which makes crossing borders and passing through checkpoints inevitable. People living with HIV experience discomfort or anxiety in disclosing their HIV status at checkpoints to be allowed to enter the area where the nearest treatment hub is. Some respondents are worried that they might be misunderstood by their health condition, moreover, discriminated against when they disclose their HIV status.

Some respondents also have difficulty accessing ARV refill because they do not have their ARV booklet which are being asked from them by their employer or treatment hub. One respondent reported that his booklet is empty because there are no logs from the hub to keep track of his quarterly issued medications due to inability to visit the clinic.

Many of the respondents suggest that viral load and CD4 Count testing should come in package together with their ARV treatment. In addition, some of the Filipinos living with HIV are still not fully educated about HIV and COVID-19. Several respondents are concerned whether there are possible adverse reactions between COVID-19 vaccines and the ARV medications that they are taking.

5. Conclusions

This study revealed that the most common barriers of medication adherence in people living with HIV are transportation and delivery, location of treatment hubs, and financial assistance. As the country continues to contain and delay the spread of COVID-19 virus, healthcare systems may miss out on patients with chronic diseases whose management may be worsened by this pandemic.

There is significant association between the following treatment barriers and sociodemographic characteristics: location of treatment hubs and respondents who finished college/graduate studies; checkpoints and crossing borders and: 1. respondents from Northern Luzon Region, 2. unemployed respondents; financial assistance and: 1. Respondents 18 to 25 years old, 2. unemployed respondents, 3. respondents who finished elementary/high school; psychosocial support and: 1. Respondents from NCR, 2. Respondents 26 to 30 years old; stocks of ARVs and other medicines and employed respondents.

Identification of treatment barriers is very important to antiretroviral therapy adherence. Many of these barriers were addressed by UNDP, UNAIDS, partner civil society organizations, several government agencies, and other development partners by working on policies and projects aimed at making HIV treatment and care services more accessible to people living with HIV in the time of COVID-19.

This study recommends to ensure continuity of their implementations for the betterment of the national HIV program. Moreover, this study strongly emphasizes the need to continue disseminating information on HIV and COVID-19 for people living with HIV and accessing treatment in the time of COVID-19, through social media platforms, newspapers and television commercials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.J.J.; methodology, P.J.J.; software, P.J.J.; validation, M.M. and R.P.; formal analysis, P.J.J. and M.M.; investigation, P.J.J.; resources, P.J.J.; data curation, M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, P.J.J.; writing—review and editing, P.J.J., M.M. and R.P.; visualization, P.J.J. and M.M.; supervision, M.M. and R.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study since there was no direct intervention and inherent risk to the participants during the conduct of research. The study was an online survey with utmost observation of patients’ data privacy. Survey forms were filled up anonymously by the participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Standard clinical practice was followed for all procedures, and participating patients’ information was anonymized.

Data Availability Statement

Data cannot be shared publicly because they are confidential. Data are available from the Department of Internal Medicine of Adventist Medical Center Manila for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank those who contributed for the completion of this research. We would like to thank Ms. May Lebanan for her help in organizing and interpreting the collected data, Mr. Gepher Canoy, for laying out the questionnaire on google forms, Mr. Benjie Obera and Ms. Felize Jemina Joves for their help in reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Introduction

Good day!

Thank you in advance for your interest in this research survey. This research aims to determine the barriers of adherence to antiretroviral therapy among people living with HIV (PLHIV) in the Philippines at the time of COVID-19 Pandemic. The participant is expected to answer all items completely and as honestly as possible.

This study will contribute to the development of programs by healthcare institutions and LGUs that will give added support to PLHIV.

All information obtained from each participant will be treated with utmost confidentiality. The data will be stored securely and only the researcher will have access to the information. If the study is eventually published or reported, no identifiable personal information of any participant will be included.

Participant’s Agreement

I am a Filipino, of legal age (18 to 60 years old), agree to participate in the research study conducted by the researcher of the Department of Internal Medicine, Adventist Medical Center Manila.

I am aware that my participation in this study is completely voluntary. If for any reason and at any time, I wish to cease my participation, I may do so without having to give any explanation. The researcher has reviewed the individual and social benefits of this project with me, and I understand the purpose of this research.

I am aware that the data gathered in this study will remain confidential and anonymous throughout the duration of the project.

I am hereby giving my consent and voluntarily participate in the data gathering of this research study:

o Yes

o No

Identification Code

Unique identifiers are needed to avoid duplicative counts for this research survey. Please type the first 2 letters of your father’s first name (e.g., Juan = JU), first 2 letters of your mother’s first name (e.g., Maria = MA), your sibling order (e.g., Eldest = 01, Second = 02, etc.) and your birthday (e.g., June 13, 2021 = 06132021).

Example Complete Unique Identifier Code: JU-MA-01-06132021

Age (years)

< 20 years old

21 - 25 years old

26 – 30 years old

31 – 35 years old

36 – 40 years old

41 – 45 years old

46 – 50 years old

> 51 years old

Region of Residence

NCR

Northern Luzon

Southern Luzon

Visayas

Mindanao

Gender Identity

Male

Female

Sexual Orientation

Homosexual

Bisexual

Heterosexual

Educational Background

Post Graduate Studies

College

High school

Elementary

Employment Status

Employed

Unemployed

Survey Questionnaire

Transportation and delivery

Location of treatment hubs

Checkpoints and crossing borders

Stock of ARVs and other medicines

Financial assistance

Employment

Psychosocial support

Verification (including ARV booklets)

Temporary shelter and housing

- 2.

Please provide more details regarding the issues you identified in the previous question.

- 3.

You may also share other HIV-related concerns that you currently have.

References

- Sundermann, E.E.; Erlandson, K.M.; Pope, C.N.; Rubtsova, A.; Montoya, J.; Moore, A.A.; Marzolini, C.; O’Brien, K.K.; Pahwa, S.; Payne, B.A.I.; Rubin, L.H.; Walmsley, S.; Haughey, N.J.; Montano, M.; Karris, M.Y.; Margolick, J.B.; Moore, D.J. Current Challenges and Solutions in Research and Clinical Care of Older Persons Living with HIV: Findings Presented at the 9th International Workshop on HIV and Aging. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2019, 35, 985–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monjok, E.; Smesny, A.; Okokon, I.B.; Mgbere, O.; Essien, E.J. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Nigeria: an overview of research studies and implications for policy and practice. HIV/AIDS – Research and palliative care 2010, 2, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Abaasa, A.M.; Todd, J.; Ekoru, K.; Kalyango, J.N.; Levin, J.; Odeke, E.; Karamagi, C.A.S. Good adherence to HAART and improved survival in a community HIV/AIDS treatment and care programme: the experience of The AIDS Support Organization (TASO), Kampala, Uganda. BMC Health Services Research 2008, 8:241.

- World Health Organization. HIV/AIDS. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and COVID 19. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/covid-19.html (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Hargreaves, J. Davey, C. Three Lessons for the COVID-19 Response from Pandemic HIV. The Lancet HIV 2020, 7, e309–e311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, W. Maintaining HIV Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic. The Lancet HIV 2020, 7, e308–e309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNAIDS. Global HIV & AIDS statistics – Fact sheet. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Karim, Q.A.; Karim, S.S.A. COVID-19 affects HIV and Tuberculosis care. Science 2020, 369, 366–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafadzwa, Dzinamarira, et al. “Risk of mortality in HIV-infected COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis”. 16 May 2022.

- Tesoriero, J.M.; Swain, C.A.E.; Pierce, J.L.; Zamboni, L.; Wu, M.; Holtgrave, D.R.; Gonzalez, C.J.; Udo, T.; Morne, J.E.; Hart-Malloy, R.; Rajulu, D.T.; Leung, S.Y.J.; Rosenberg, E.S. COVID-19 outcomes among persons living with or without diagnosed HIV infection in New York State. JAMA Network Open 2014, 4, e2037069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilon, X.J. Leaving No One Behind. Treatment and Care Concerns of People Living with HIV in the Time of COVID-19 (A Philippine Situationer). UNDP 2021, 1-8.

- Collin, J.; Hadzmy, A.J.b.A. Coming out strategies on social media among young gay men in Malaysia. Youth 2022, 2, 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman, S.C.; Eaton, L.A.; Berman, M.; Kalichman, M.O.; Katner, H.; Sam, S.S.; Calinedo, A.M. ; Intersecting Pandemics: Impact of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) Protective Behaviors on People Living with HIV, Atlanta, Georgia. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2020, 85, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiau, S.; Krause, K.D.; Valera, P.; Swaminathan, S.; Halkitis, P.N. ; The Burden of COVID-19 in People Living with HIV: A Syndemic Perspective. Springer 2020, 24, 2244–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chenneville, T.; Gabbidon, K.; Hanson, P.; Holyfield, C. ; The Impact of COVID-19 on HIV Treatment and Research: A Call to Action. Int. J. of Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dada, D.A.; Aku, E.; David, K.B. ; COVID-19 pandemic and antiretrovirals (ARV) availability in Nigeria: recommendations to prevent shortages. PAMJ 2020, 35, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballester-Arnal, R.; and Gil-Llario, M.D. ; The Virus That Changed Spain: Impact of COVID-19 on People with HIV. Springer 2020, 24, 2253–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manchia, M.; Gathier, A. W.; Yapici-Eser, H.; Schimdt, M.V.; de Quervain, D.; van Amerlsvoort, T.; Bisson, J.I.; Cryan, J.F.; Howes, O.D.; Pinto, L.; van der Wee, N.J.; Domschke, K.; Branchi, I.; Vinkers, C.H. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on stress resilience and mental health: A critical review across waves. Elsevier 2022, 55, 22–83. [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw, V.A.; Smith, L.R.; Chaudoir, S.R.; Amico, K.R.; Copenhaver, M.M. ; HIV Stigma Mechanisms and Well-Being among PLWH: A Test of the HIV Stigma Framework. AIDS Behav. 2013, 17, 1785–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballivian, J.; Alcaide, M.L.; Cecchini, D.; Jones, D.L.; Abbamonte, J.M.; Cassetti, I. Impact of COVID–19-Related Stress and Lockdown on Mental Health among People Living with HIV in Argentina. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2020, 85, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shippy, R.A.; Karpiak, S.E. Perceptions of support among older adults with HIV. Research on Aging 2005, 27, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, T.G.; Halkitis, P.N. Biopsychosocial aspects of HIV and aging. Behavioral Medicine 2014, 40, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.C.; Fazeli, P.L.; Jeste, D.V.; Moore, D.J.; Grant, I.; Woods, S.P. Successful cognitive aging and health-related quality of life in younger and older adults infected with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2014, 18, 1186–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, E.E.; Iudicello, J.E.; Weber, E.; Duarte, N.A.; Riggs, P.K.; Delano-Wood, L.; Ellis, R.; Grant, I.; Woods, S.P. Synergistic effects of HIV infection and older age on daily functioning. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr 2012, 61, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valcour, V.; Paul, R.; Neuhaus, J.; Shikuma, C. The effects of age and HIV on neuropsychological performance. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2011, 17, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, R.; Nellums, L.B. ; COVID-19 and the Consequences of Isolating the Elderly. The Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, J.; Jackson, D. ; Older People and COVID-19: Isolation, Risk and Ageism. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2020, 29, 2044–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halkitis, P.N.; Krause, K.D.; Vieira, D.L. Mental health, psychosocial challenges and resilience in older adults living with HIV. Interdiscip Top Gerontol Geriatr 2017, 42, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hanghøj, S.; Boisen, K.A. Self-reported barriers to medication adherence among chronically ill adolescents: a systematic review. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 54, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kretchy, I.A.; Owusu-Daaku, F.; Danquah, S.A. Mental health in hypertension: assessing symptoms of anxiety, depression and stress on anti-hypertensive medication adherence. Int. j. Ment. Health Syst. 2014, 8, 25–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salleh, M.R. life event, stress and illness. MJMS 2008, 15, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kretchy, I.A.; Asiedu-Danso, M.; Kretchy, J.P. Medication management and adherence during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Perspectives and experiences from low-and middle-Income countries”. Elsevier 2021, 17, 2023–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).