1. Introduction

Nurses hold a pivotal role in disaster response, necessitating a comprehensive understanding of typical disaster patterns. The discipline of disaster nursing aims to offer patient care to affected populations while also participating in disaster planning and preparedness at all levels. One study conducted on nurses dispatched to the Ya'an earthquake in 2013 underscored the necessity for well-articulated disaster plans and emergency in-service education [

1] .Research conducted in Saudi Arabia revealed that emergency nurses often lack the required knowledge concerning disaster planning and management[

1]. To enhance their disaster response capabilities, the study participants suggested three key training initiatives. However, nurses often encounter several challenges in the field of disaster nursing. These include a lack of preparedness, inadequate formal education, insufficient research, ethical and legal dilemmas, and lack of exposure to disaster situations. Therefore, to foster growth in disaster nursing, concerted efforts from educators, researchers, and practitioners are essential [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6] .

It is recommended that nursing programs incorporate disaster nursing components, thereby equipping nurses with the necessary skills and knowledge for effective disaster response and patient care [

7] . Well-prepared nurses can significantly mitigate the adverse impacts of disasters on communities [

8]. By participating in educational programs and disaster response exercises, nurses can acquire expertise and competence in managing catastrophic situations [

9] . The use of simulated drills and exercises, complemented by regular assessments, can significantly enhance nursing skills. A solid understanding of the core principles of crisis management is crucial for nurses to perform effectively during catastrophic events [

9,

10,

11] .Despite a growing need for disaster preparedness and healthcare responders in Saudi Arabia, there remains a significant gap in education and training in this sector [

12]. A study conducted in the region identified incident management systems, disaster triage, and disaster drills as essential elements of education and training for emergency nurses, especially those with less than three years of experience [

13,

14,

15].

Disaster triage pertains to the process of prioritizing medical care for the ill and injured during a disaster situation [

13,

16,

17]. It involves segregating patients according to their medical needs and is generally carried out in three stages: at the disaster scene, during transit to a medical facility, and upon arrival at the hospital [

16,

18,

19]. Triage categories typically encompass emergency, urgent, non-urgent, and dying or deceased [

20] . The nurse assigned to triage plays a vital role in categorizing patients based on their medical priority, necessitating the possession of appropriate knowledge and skills[

21,

22,

23] .Simulation training methods, such as tabletop exercises, can aid in enhancing the clinical decision-making skills of nursing students [

21,

24]. These exercises, which can range from simple to more complex scenarios, involve reviewing operational plans, identifying potential areas of improvement, and promoting constructive dialogue [

6,

25].

In the context of Saudi Arabia, disaster preparedness studies tend to focus on (a) general preparedness assessment, (b) core competencies, and (c) disaster planning [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31] . However, these studies have a limited scope, particularly in the realms of education and training. The current methodologies for preparing nursing professionals in Saudi Arabia are deemed insufficient, with a notable lack of disaster drills, especially simulation exercises, being a key shortcoming in the education and training of emergency nurses [

20,

30,

31,

32,

33]. The primary objective of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of simulation-based training in improving nursing students' knowledge and performance in crisis management and triage during mass casualty incidents. The study will employ a scenario based on a mass casualty event with the aim of identifying gaps and challenges, and consequently enhancing the existing protocols in disaster management.

2. Materials and Methods

Detailed Research Design and Procedure

The research study was designed to be a quantitative interventional pre-post study, the purpose of which was to understand the impact of a training intervention on the disaster nursing skills of students at the College of Nursing, Taif University, located in Saudi Arabia. The selection of participants involved a random sampling of 101 nursing students from a total pool of 135 students, done with the help of the Open Epi sample calculation program, ensuring a confidence level of 95% for the study. The participants were all sixth-level nursing students who agreed to be a part of the study voluntarily. It was essential that they completed both the pre- and post-test evaluations as part of the study protocol.

The simulation that was used for this study was carefully designed to reflect a realistic disaster scenario, which involved a train accident with 80 passengers needing immediate triage and transportation. The response team for this simulated disaster was made up of ten nurses, five doctors, and ten paramedics, all of whom were led by an emergency and disaster specialist. The response team was well-equipped with all the necessary tools required for triage, transport, and disability assistance. Additional support was provided by several other hospitals that made 30 ambulances available for the exercise. The simulation also included law enforcement personnel to maintain security, creating a realistic disaster response scenario.

The research study made use of a detailed questionnaire to measure the emergency management skills and efficiency of the nursing students. The questionnaire was designed based on a Five-Point Likert Scale and was divided into three parts: socio-demographic characteristics of the students, their knowledge related to managing Mass Casualty Incidents (MCI), and a simulated MCI. The third part of the questionnaire presented the students with scenarios that required them to triage patients based on various medical conditions and vital signs. In terms of data collection, a pre-test and post-test system was used to evaluate the knowledge and understanding of the students both before and after the training intervention. The pre-test served as a benchmark to measure the initial knowledge levels of the students, while the post-test was designed to measure the effectiveness of the training intervention.

Elaborate Simulation Setup

The simulation setup for the study was complex and involved the use of three whiteboards, each representing different aspects of the disaster scenario. To maintain student anonymity during the pre- and post-event questionnaires, each student was assigned a unique serial number. The first whiteboard was used to represent the external area of the simulated event. It included representations of journalists, police, and civil defense patrols to create a realistic external environment of a real disaster. The second whiteboard was designed to depict the triage and transport section of the disaster response scenario. It included representations of ambulances, medical staff, and patient cards for the triage process. The third whiteboard represented the lecture room. This is where students were introduced to the study topic, assessed using the barcode system, and given a post-test to evaluate their understanding of the material covered.

The simulation was conducted over two consecutive days, with separate groups attending each day. Attendance was recorded, and serial numbers were assigned before each session. The collected data was analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 29. Descriptive analysis and Paired Sample T-Test were used to understand the data and identify any significant differences. A P-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. The study was completely voluntary, and students could withdraw at any stage. Permissions to use the scales were obtained from the original authors, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). There were no expected risks, costs, or payments associated with participation in the research project.

3. Results

The participants are fairly evenly distributed in terms of gender, with males making up 50.4% (62) and females 49.6% (61) of the total. When it comes to clinical experience, a majority of the participants, 59.3% (73), have had some form of experience, while 40.7% (50) have not. The table also breaks down the specific training courses related to triage or Rapid Response (RR) procedures that the participants have undergone. The most common of these is Basic Life Support (BLS) with 59.3% (73) of participants having this training. Only a small percentage of participants have taken Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) at 1.6% (2) or Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) and Advanced Trauma Care for Nurses (ATCN) at 2.4% (3). Meanwhile, 36.6% (45) of participants have not undergone any of these training courses (

Table 1).

The total score, the mean (M) score reduced from 31.47 in the pre-test to 27.52 in the post-test, while the standard deviation (S.D) also decreased from 10.76 to 8.03. In the category of 'Red', the mean score decreased from 3.36 (pre-test) to 2.66 (post-test), and the standard deviation also reduced from 1.39 to 1.16. For the 'Green' category, the average score remained nearly the same, from 2.46 in the pre-test to 2.5 in the post-test, with a slight decrease in the standard deviation from 1.73 to 1.58. The 'Yellow' category witnessed a decrease in the mean score from 2.96 (pre-test) to 2.52 (post-test), while the standard deviation marginally increased from 2.46 to 2.51. Lastly, the 'Black' category showed a slight decrease in the mean score from 4.26 (pre-test) to 4.14 (post-test), with an increase in the standard deviation from 1.77 to 1.88 (

Table 2)

.

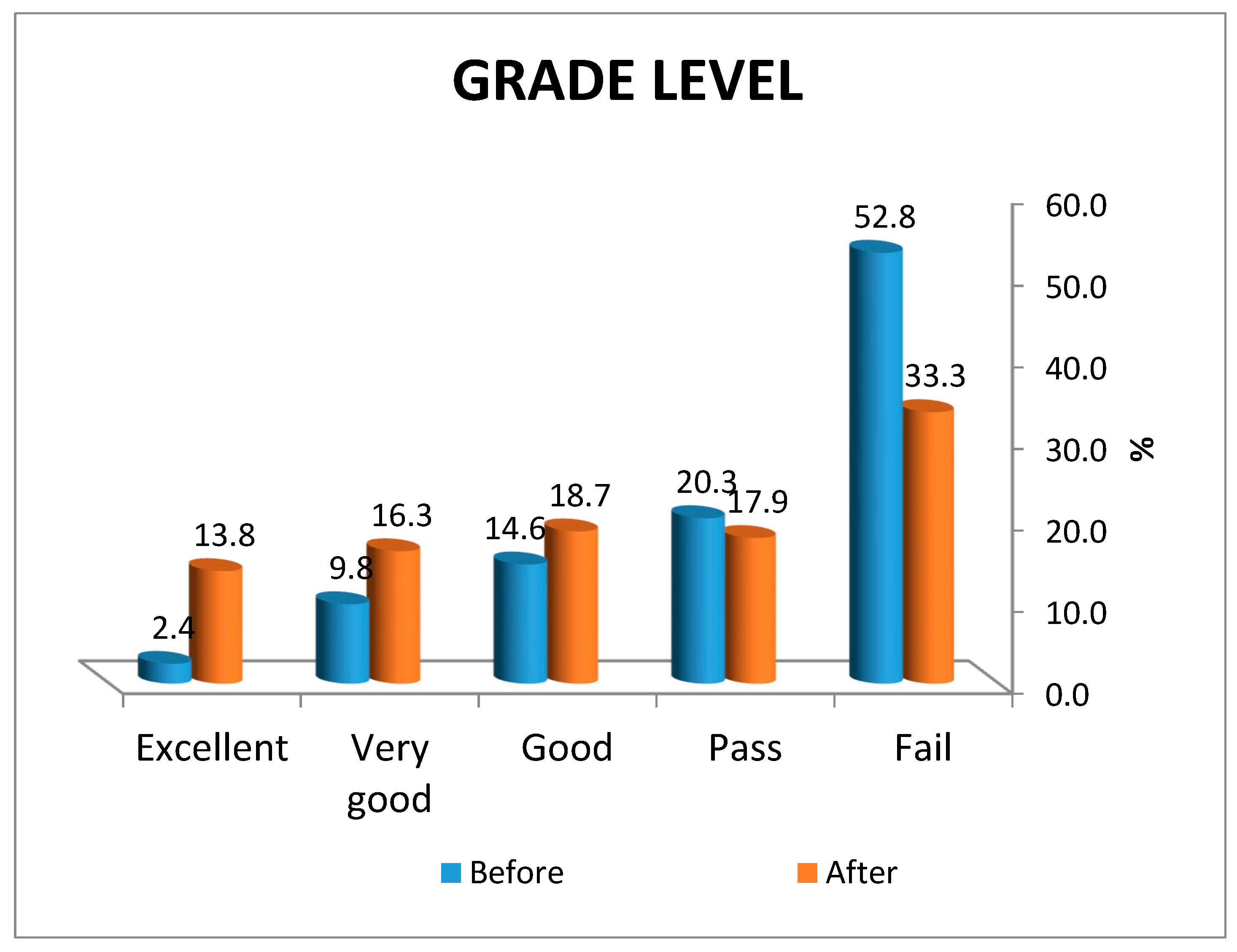

Posttest grades level excellent (f = 17, % = 13.8), very good (f = 20, % = 16.3), good (f = 23, % = 18.7), pass (f = 22, % = 17.9), and fail (f = 41, % = 33.3), and Pretest grades level excellent (f = 3, % = 2.4), very good (f = 12, % = 9.8), good (f = 18, % = 14.6), pass (f = 25, % = 20.8), and fail (f = 65, % = 52.8)

Table 3.

The majority of the Knowledge item related to Mass Casualty Incident pretest and posttest (MCI) represent (13.8%,16.3%, 18.7%,20.3%, 52.8%) (Excellent, very good, Good, Pass, Fail), respectively (

Figure 1).

The pre-test means of item related to Mass Casualty Incident ( MCI)knowledge M± SD mean score was (3.55+0.94, 3.52+0.95, 3.5+1.02, 3.43+0.98, 3.42+0.89, 3.06+0.95, 3.04+1.02, 2.8+0.91, 2.63+0.94, 2.48+0.88, 2.36+0.78) respectively while after training posttest mean of item related to Mass Casualty Incident ( MCI) knowledge M± SD mean score was (3.58+2.27, 4.27+1.77, 2.56+2.51, 3.62+2.25c2.97+2.47, 3.7+2.2, 4.11+1.71, 2.93+2.47, 1.83+2.42, 1.91+2.44, 1.91+2.44) respectively (

Table 4).

There was No significant correlation between Knowledge items related to Mass Casualty Incident (MCI) related to reflects the Mass Casualty (r = –.004, N = 123, p =0.968, Tow-tailed) Pertest education But There was a significant Positive correlation Posttest education. The scatterplot shows that the data points are reasonably well distributed along the regression line, in a linear relationship with no outliers (

Table 5).

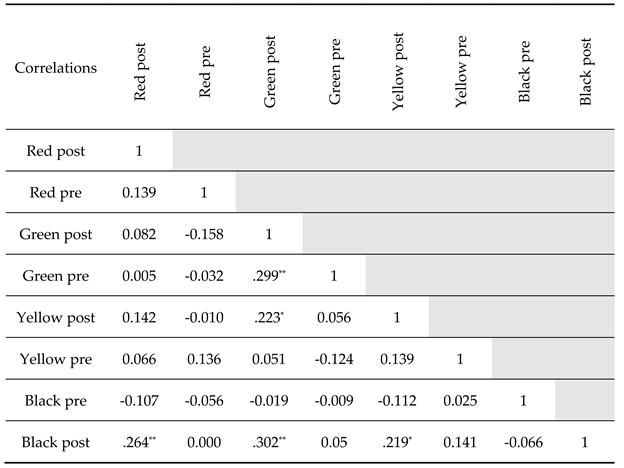

There is statistical significant correlation between yellow post and black post, yellow pre p. value (.223* and .219*) and was statistical significant correlation between Green pre and post (.299**) Black post, Red post and Green post(.264**, .302**) (

Table 6).

4. Discussion

In high-stakes situations like catastrophic disasters, where split-second decisions can mean the difference between life and death, the importance of diligence, skill, and quick thinking cannot be overstated. Practice plays a crucial role in developing practitioners who can excel in such critical moments. Since disasters are inevitable, being prepared is essential for effective disaster management. Nursing educators and numerous national and international nursing organizations have recognized the significance of this aspect and have worked towards incorporating it into the curriculum by identifying a set of optimal competencies [

25,

34,

35]. The aim of this study was to assess the impact of a training intervention on disaster nursing students, with the goal of better preparing them for such situations in the future.

The participant demographics and training background were characterized by a fairly equal distribution of gender, with males comprising 50.4% (62 individuals) and females accounting for 49.6% (61 individuals) of the total sample. This study presents a notable departure from previous research in Saudi Arabia, where the majority of participants were female nurses. In contrast, this study observed an equal number of male and female student nurses at Taif University. This finding highlights a shift in participant demographics and underscores the importance of inclusivity in research to capture a more comprehensive understanding of the nursing profession and healthcare landscape. The majority of participants (59.3%, 73 individuals) had prior clinical experience, while 40.7% (50 individuals) did not. Basic Life Support (BLS) was the most common training course completed (59.3%, 73 individuals), followed by a small percentage with advanced training in courses such as ACLS, ATLS, and ATCN (1.6%-2.4%, 2-3 individuals). Notably, a significant portion (36.6%, 45 individuals) had not received any of these specific training courses.These demographics and training background variations provide valuable context for understanding the participants' preparedness and expertise in the field of triage and Rapid Response procedures. Therefore, Considering the diverse backgrounds and previous training experiences of participants, it is essential to develop a training program that caters to individual needs [

9,

13,

27]. Customizing the program to address specific gaps in knowledge and skills identified through the analysis can help improve participants' preparedness in triage and Rapid Response procedures[

36].Additionaally, Offer advanced training courses like ACLS, ATLS, and ATCN to enhance expertise in managing complex situations[

37]. Collaborate with healthcare institutions to facilitate access to these courses.

The analysis of participants' performance in both pretest and post-test assessments revealed a decline in mean scores and standard deviations following the training intervention. Overall performance showed a decrease, with the average score dropping from 31.47 in the pretest to 27.52 in the post-test. Specifically, performance in the 'Red' and 'Yellow' categories showed a decline, while the 'Green' category remained relatively stable. The 'Black' category experienced a minor decrease as well. These findings underscore the need for additional support and improvement in participants' knowledge and skills related to triage and Rapid Response procedures. Therefore, it is crucial for nursing schools to enhance nursing students' understanding and abilities in prioritizing patients based on the severity of their condition[

38,

39]. This can be achieved by providing supplementary training, education, resources, and mentorship to help students develop the necessary knowledge and skills, ensuring they are well-prepared before entering their careers in hospitals[

40,

41]. Comprehensive education and training should encompass both theoretical and practical aspects, with a particular focus on vital skills such as communication and decision-making[

13,

42,

43].

The analysis of the participants' posttest grades indicated a significant improvement in performance compared to the pretest. The results of the posttest showed that a notable percentage of participants achieved higher grades: 13.8% attained an excellent level, 16.3% received a very good level, and 18.7% obtained a good level grade, indicating a positive outcome resulting from the training intervention. However, a smaller proportion of participants received pass level grades (17.9%), while 33.3% obtained a fail level grade, suggesting areas where further improvement may be necessary. In the pretest, the distribution of grades was less favorable, with only 2.4% achieving an excellent level grade, 9.8% receiving a very good level grade, and 14.6% obtaining a good level grade. These findings underscore the effectiveness of the training program in enhancing participants' knowledge and performance in triage and Rapid Response procedures. In conclusion, the training program has successfully improved participants' understanding and performance in triage and Rapid Response procedures[

44]. By providing nursing students with training in disaster triage, they will be better equipped to handle emergency situations, assess and prioritize patients, make informed decisions, communicate effectively with the team, and respond swiftly to critical situations[

45,

46]. Given the importance of training nursing students in the domain of disaster triage and rapid response, investing in training will result in tangible benefits by improving emergency response capabilities and potentially enhancing patient outcomes[

47,

48].

The analysis of knowledge items pertaining to Mass Casualty Incidents (MCI) demonstrated that participants' performance improved following the training intervention. The average scores in the posttest were generally higher compared to the scores in the pretest, indicating an enhancement in participants' comprehension of concepts related to MCIs. While there was no significant correlation observed between knowledge items in the pretest, a significant positive correlation was found between posttest education and performance on knowledge items. This suggests that the training program had a positive impact on participants' acquisition of knowledge, resulting in improved scores in the posttest. These findings highlight the importance of targeted and focused training programs in effectively addressing the complexities and challenges associated with mass casualty incidents or disasters. Such training programs enable nursing students to efficiently triage and prioritize patients, coordinate resources and personnel, implement effective communication strategies, and manage the overall response process[

49,

50]. Overall, these findings underscore the effectiveness of targeted training in enhancing participants' knowledge and performance in topics related to MCIs.

The analysis of correlations among posttest knowledge items revealed noteworthy findings. Significant positive correlations were observed between different pairs of items, indicating connections between participants' understanding of these concepts. For instance, nursing students who performed well on the Yellow Post item also tended to perform well on the Black Post item, suggesting a relationship between these two areas of knowledge. Similarly, a positive correlation was found between the Yellow Pre and Yellow Post items, indicating that students retained and reinforced their knowledge in this specific domain. The correlation between the Green Pre and Green Post items indicated consistent improvement in students' understanding of the Green topic. Furthermore, there was a significant positive correlation among the Black Post, Red Post, and Green Post items, suggesting shared knowledge or skills across these areas. These findings highlight the interconnected nature of the training intervention and its effectiveness in enhancing students’ knowledge across various interconnected areas related to Mass Casualty Incidents (MCI) and disaster triaging[

1,

12,

28,

40]. Additionally, the targeted training approach proved effective in improving students' performance in specific knowledge items pertaining to MCI [

9,

10,

16].

5. Limitation

Limitations exist regarding nursing students' understanding and competency development in tragedy care. The descriptive and post-analysis research design has limitations, and a qualitative research design is needed for in-depth understanding. The region students may have limitations in understanding the simulation process, which is another limitation. Finally, there is a limitation in understanding confounding variables, such as environmental consequences, situational factors, and event concerns, which can affect patient care.

6. Recommendation

1. Customize the training program to meet individual needs based on participants' diverse backgrounds and previous training experiences.

2. Offer advanced training courses like ACLS, ATLS, and ATCN to enhance expertise in managing complex situations. Collaborate with healthcare institutions for access.

3. Focus on enhancing nursing students' understanding and abilities in triage, prioritizing patients based on severity. Provide supplementary training, resources, and mentorship.

4. Provide comprehensive education and training in disaster triage, covering both theory and practice. Emphasize vital skills such as communication and decision-making.

5. Invest in disaster triage training for nursing students to improve emergency response capabilities and patient outcomes.

7. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study emphasizes the importance of diligent preparation and training in disaster nursing. Customized training programs and advanced courses can enhance participants' preparedness and expertise. Additional support and improvement are needed to enhance participants' knowledge and skills. Nursing schools should focus on prioritizing patient care and providing comprehensive education and training. The training program effectively improved participants' knowledge and performance. Investing in training nursing students in disaster triage contributes to improved patient outcomes. Targeted training programs enhance comprehension of concepts related to mass casualty incidents (MCI) and disaster triaging. Overall, this study highlights the significance of training and education in disaster nursing for improved emergency response and patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the deanship of scientific research at Taif University for funding this study. They also acknowledge the continuous support provided by the Deanship of Postgraduate Studies at Taif University.

Disclosure: The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Alzahrani, F.; Kyratsis, Y. Emergency nurse disaster preparedness during mass gatherings: a cross-sectional survey of emergency nurses' perceptions in hospitals in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. BMJ open 2017, 7, e013563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Harthi, M.; et al. Challenges for nurses in disaster management: a scoping review. Risk management and healthcare policy, 2020: p. 2627-2634.

- Li, Y.; et al. Disaster nursing experiences of Chinese nurses responding to the Sichuan Ya'an earthquake. International nursing review 2017, 64, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, S.; Kondo, A.; Takamura, Y. Practices and challenges of disaster nursing for Japanese nurses sent to Nepal following the 2015 earthquake. Health Emergency and Disaster Nursing 2020, 7, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourvakhshoori, N.; et al. Nursing in disasters: A review of existing models. International emergency nursing 2017, 31, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, R.; Daily, E. International disaster nursing. 2010: Cambridge University Press.

- Latif, M.; Abbasi, M.; Momenian, S. The Effect of Educating Confronting Accidents and Disasters on the Improvement of Nurses’ Professional Competence in Response to the Crisis. Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2019, 4, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenema, T.G.; et al. Call to action: the case for advancing disaster nursing education in the United States. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 2017, 49, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalanlar, B. Effects of disaster nursing education on nursing students’ knowledge and preparedness for disasters. International journal of disaster risk reduction 2018, 28, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loke, A.Y.; Guo, C.; Molassiotis, A. Development of disaster nursing education and training programs in the past 20 years (2000–2019): A systematic review. Nurse education today 2021, 99, 104809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, C.H.; et al. Development of national standardized all-hazard disaster core competencies for acute care physicians, nurses, and EMS professionals. Annals of emergency medicine 2012, 59, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Thobaity, A.; et al. Perceptions of knowledge of disaster management among military and civilian nurses in Saudi Arabia. Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal 2015, 18, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinjee, D.; et al. Identify the disaster nursing training and education needs for nurses in Taif City, Saudi Arabia. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 2021: p. 2301-2310.

- Noh, J.; et al. Development and evaluation of a multimodality simulation disaster education and training program for hospital nurses. International journal of nursing practice 2020, 26, e12810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.C.; et al. Interprofessional disaster simulation during the COVID-19 pandemic: adapting to fully online learning. Clinical Simulation in Nursing 2022, 63, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazyar, J.; Farrokhi, M.; Khankeh, H. Triage systems in mass casualty incidents and disasters: a review study with a worldwide approach. Open access Macedonian journal of medical sciences 2019, 7, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassallo, J.; et al. Major incident triage: derivation and comparative analysis of the Modified Physiological Triage Tool (MPTT). Injury 2017, 48, 992–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadashzadeh, A.; Khani, J.; Soleymani, M. Triage in the mass casualties in pre-hospital emergency. Journal of Injury and Violence Research 2019, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Glauberman, G.H.; et al. Disaster aftermath interprofessional simulation: promoting nursing students' preparedness for interprofessional teamwork. Journal of Nursing Education 2020, 59, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranse, J.; Zeitz, K. Disaster triage. International Disaster Nursing, 2010: p. 57-80.

- Farhadloo, R.; et al. Investigating the effect of training with the method of simulation on the knowledge and performance of nursing students in the pre-hospital Triage. Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2018, 3, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; et al. Does theme game-based teaching promote better learning about disaster nursing than scenario simulation: A randomized controlled trial. Nurse education today 2021, 103, 104923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; et al. The impact of simulation-based triage education on nursing students' self-reported clinical reasoning ability: a quasi-experimental study. Nurse Education in Practice 2021, 50, 102949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, M.; et al. Educational intervention in triage with the Swedish triage scale RETTS©, with focus on specialist nurse students in ambulance and emergency care–A cross-sectional study. International emergency nursing 2022, 63, 101194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, W.J.; Lee, J. Effectiveness of the infectious disease (COVID-19) simulation module program on nursing students: disaster nursing scenarios. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing 2021, 51, 648–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, B.; et al. Virtual reality triage training can provide comparable simulation efficacy for paramedicine students compared to live simulation-based scenarios. Prehospital Emergency Care 2020, 24, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, M.S.Y.; et al. The effectiveness of disaster education for undergraduate nursing students’ knowledge, willingness, and perceived ability: An evaluation study. International journal of environmental research and public health 2021, 18, 10545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshehri, B. Emergency nurses’ preparedness for disaster in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J Nurs Educ Pract 2017, 7, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, O.G.; Alamri, A.A.; Aboshaiqah, A.E. A descriptive study to analyse the disaster preparedness among Saudi nurses through self-regulation survey. Journal of nursing management 2019, 27, 1479–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Thobaity, A.; et al. Exploring the necessary disaster plan components in Saudi Arabian hospitals. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2019, 41, 101316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Thobaity, A.; Williams, B.; Plummer, V. A new scale for disaster nursing core competencies: development and psychometric testing. Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal 2016, 19, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.S.; et al. Nursing student's attitudes toward teams in an undergraduate interprofessional mass casualty simulation. in Nursing forum. 2021. Wiley Online Library.

- Demir, S.; Tunçbilek, Z.; Alinier, G. The effectiveness of online Visually Enhanced Mental Simulation in developing casualty triage and management skills of paramedic program students: A quasi-experimental research study. International Emergency Nursing 2023, 67, 101262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, M.M.; Dufrene, C. Educational competencies and technologies for disaster preparedness in undergraduate nursing education: an integrative review. Nurse Education Today 2014, 34, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslu, Y.; Unver, V.; Karabacak, U. Hybrid simulation in triage training. International Journal of Caring Sciences 2019, 12, 1626. [Google Scholar]

- King, R.V.; et al. Attributes of effective disaster responders: focus group discussions with key emergency response leaders. Disaster medicine and public health preparedness 2010, 4, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, B.E.; Carr, K.V.; Padden, D.L. Self-assessment of trauma competencies among army family nurse practitioners. Military medicine 2008, 173, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, H.B.; Williams, B.A.; Man, C.Y. Nursing students' clinical judgment in high-fidelity simulation based learning: a quasi-experimental study. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice 2014, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delnavaz, S.; et al. Comparison of scenario based triage education by lecture and role playing on knowledge and practice of nursing students. Nurse education today 2018, 70, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, J.P.; et al. Psychometric assessment of the learning needs for disaster nursing scale Arabic version among baccalaureate nursing students in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2023, 91, 103689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, R.M.; et al. Exploring Factors and Challenges Influencing Nursing Interns’ Training Experiences in Emergency Departments in Saudi Arabia. International Medical Education 2023, 2, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Alharbi, N.S.; et al. Saudi Emergency Nurses Preparedness For Biological Disaster Management At The Governmental Hospitals. Journal of Positive School Psychology 2022, 6, 1218–1235. [Google Scholar]

- Bajow, N.; et al. Disaster health education framework for short and intermediate training in Saudi Arabia: A scoping review. Frontiers in public health 2022, 10, 932597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, M.A.S.; et al. Disaster Collaborative Exercises for Healthcare Teamwork in a Saudi Context. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 2023: p. 1-11.

- Shirazi, F.B.; et al. Identifying the Challenges of Simulating the Hospital Emergency Department in the Event of Emergencies and Providing Effective Solutions: A Qualitative Study. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 2023, 17, e202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; et al. Development and evaluation of innovative and practical table-top exercises based on a real mass-casualty incident. Disaster medicine and public health preparedness 2023, 17, e200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adini, B.; et al. Assessing levels of hospital emergency preparedness. Prehospital and disaster medicine 2006, 21, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousefian, S.; Sohrabizadeh, S.; Jahangiri, K. Identifying the components affecting intra-organizational collaboration of health sector in disasters: Providing a conceptual framework using a systematic review. International journal of disaster risk reduction 2021, 57, 102146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization, W.H. Hospital emergency response checklist: an all-hazards tool for hospital administrators and emergency managers. 2011, World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe.

- Glow, S.D.; et al. Managing multiple-casualty incidents: a rural medical preparedness training assessment. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 2013, 28, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).