Submitted:

28 August 2023

Posted:

01 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

- (1)

- Does Viral clearance really mean a disease resolution? That would be mandatory to determine to really weight a significant long term impact on natural history of HCV.

- (2)

- We now have more then 5 years follow-up however still remain unknown a long-term follow-up) more than 10 years about clinical evolution of viral disease (ascites, variceal bleeding, hepato-renal syndrome, hepatic encephalopathy, and hepatocellular carcinoma). Particularly, we do not have decisive findings regarding these outcomes in real life settings and this would be fundamental in the health care system management.

Methods

Study design and patients’ population

Patients follow-up

Liver stiffness evaluation

Endpoints of study

Statistical Analysis

Results

Discussion

References

- Sulkowski, M.S.; Vargas, H.E.; Di Bisceglie, A.M.; Kuo, P.A.; Reddy, K.R.; Lim, J.K.; et al. Effectiveness of Simeprevir plus Sofosbuvir, With or Without Ribavirin, in Real-World Patients with HCV Genotype 1 Infection. Gastroenterology 2015, 150, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, G.N.; Beste, L.A.; Chang, M.F.; Green, P.K.; Lowey, E.; Tsui, J.I.; Su, F.; Berry, K. Effectiveness of Sofosbuvir, Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir, or Paritaprevir/Ritonavir/Ombitasvir and Dasabuvir Regimens for Treatment of Patients With Hepatitis C in the Veterans Affairs National Healthcare System. Gastroenterology 2016, 151, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwo, P.; Gane, E.J.; Peng, C.Y.; Pearlman, B.; Vierling, J.M.; Serfaty, L.; Buti, M.; Shafran, S.; Stryszak, P.; Lin, L.; Gress, J.; Black, S.; Dutko, F.J.; Robertson, M.; Wahl, J.; Lupinacci, L.; Barr, E.; Haber, B. Effectiveness of Elbasvir and Grazoprevir Combination, With or Without Ribavirin, for Treatment-Experienced Patients With Chronic Hepatitis C Infection. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reig, M.; Mariño, Z.; Perelló, C.; Iñarrairaegui, M.; Ribeiro, A.; Lens, S.; Díaz, A.; Vilana, R.; Darnell, A.; Varela, M.; Sangro, B.; Calleja, J.L.; Forns, X.; Bruix, J. Unexpected early tumor recurrence in patients with hepatitis C virus –related hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing interferon-free therapy: A note of caution. J Hepatol 2016, 65, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, H.; Vale, A.M.; Rodrigues, S.; et al. High incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma following successful interferon-free antiviral therapy for hepatitis C associated cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2016, 65, 1070–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinaldi, L.; Perrella, A.; Guarino, M.; De Luca, M.; Piai, G.; Coppola, N.; Pafundi, P.C.; Ciardiello, F.; Fasano, M.; Martinelli, E.; Valente, G.; Nevola, R.; Monari, C.; Miglioresi, L.; Guerrera, B.; Berretta, M.; Sasso, F.C.; Morisco, F.; Izzi, A.; Adinolfi, L.E. Incidence and risk factors of early HCC occurrence in HCV patients treated with direct acting antivirals: A prospective multicentre study. J Transl Med. 2019, 17, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Serag, H.B.; Kanwal, F.; Richardson, P.; Kramer, J. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma after sustained virological response in Veterans with hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2016, 64, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahon, P.; Bourcier, V.; Layese, R.; et al. Eradication of hepatitis C virus infection in patients with cirrhosis reduces risk of liver and non-liver complications. Gastroenterology. 2017, 152, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazawi, W.; Cunningham, M.; Dearden, J.; Foster, G.R. Systematic review: Outcome of compensated cirrhosis due to chronic hepatitis C infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010, 32, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattovich G, Pantalena M, Zagni I et al. Effect of hepatitis B and C virus infections on the natural history of compensated cirrhosis: A cohort study of 297 patients. Am J Gastroenterol 2002, 97, 2886–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ambrosio, R.; Della Corte, C.; Colombo, M. Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients with a Sustained Response to Anti-Hepatitis C Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 19698–19712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, R.L.; Baack, B.; Smith, B.D.; Yartel, A.; Pitasi, M.; Falck-Ytter, Y. Eradication of hepatitis C virus infection and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2013, 158, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanwal, F.; Khaderi, S.; Singal, A.G.; Marrero, J.A.; Loo, N.; Asrani, S.K.; Amos, C.I.; Thrift, A.P.; Gu, X.; Luster, M.; Al-Sarraj, A.; Ning, J.; El-Serag, H.B. Risk factors for HCC in contemporary cohorts of patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 2023, 77, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Associazione Italiana per lo Studio del Fegato. Documento di indirizzo dell’Associazione Italiana per lo Studio del Fegato per l’uso razionale di antivirali diretti di seconda generazione nelle categorie di pazienti affetti da epatite C cronica ammesse alla rimborsabilità in Italia. Available at webaisf.org/pubblicazioni/documento-aisf-hcv-2016.aspx.

- Boursier, J.; Zarski, J.P.; de Ledinghen, V.; Rousselet, M.C.; Sturm, N.; Lebail, B.; Fouchard-Hubert, I.; Gallois, Y.; Oberti, F.; Bertrais, S.; Calès, P.; Multicentric Group from ANRS/HC/EP23 FIBROSTAR Studies. Determination of reliability criteria for liver stiffness evaluation by transient elastography. Hepatology 2013, 57, 1182–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012, 56, 908–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forner, A.; Reig, M.E.; de Lope, C.R.; Bruix, J. Current strategy for staging and treatment: The BCLC update and future prospects. Semin Liver Dis 2010, 30, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, R.; Hydes, T.; Khakoo, S.I. Innate and adaptive genetic pathways in HCV infection. Tissue Antigens. 2015, 85, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Li, Y.; Chang, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, F.S. Current progress in host innate and adaptive immunity against hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatol Int. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Perrella, A.; Sbreglia, C.; Atripaldi, L.; Esposito, C.; D'Antonio, A.; Perrella, O. Rapid virological response in peripheral blood mononuclear cells with an increase of hepatitis C virus-specific interferon-gamma production predisposes to sustained virological response in patients with chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 undergoing treatment with pegylated-interferon alpha 2a plus ribavirin. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010, 45, 250–255. [Google Scholar]

- van der Ree, M.H.; Stelma, F.; Willemse, S.B.; Brown, A.; Swadling, L.; van der Valk, M.; Sinnige, M.J.; van Nuenen, A.C.; de Vree, J.M.L.; Klenerman, P.; Barnes, E.; Kootstra, N.A.; Reesink, H.W. Immune responses in DAA treated chronic hepatitis C patients with and without prior RG-101 dosing. Antiviral Res. 2017, 146, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, M.; Deng, X.; Zhai, X.; Xu, K.; Kong, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, X.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, Y. Th1 and Th2 cytokine profiles induced by hepatitis C virus F protein in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from chronic hepatitis C patients. Immunol Lett. 2013, 152, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, X.J.; Ye, F.; Li, X.Y.; Liu, W.T.; Jing, Y.Y.; Han, Z.P.; Wei, L.X. Immune response involved in liver damage and the activation of hepatic progenitor cells during liver tumorigenesis. Cell Immunol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, J.M.; Adenugba, A.; Protzer, U. Immune Reconstitution After HCV Clearance With Direct Antiviral Agents: Potential Consequences for Patients With HCC? Transplantation. 2017, 101, 904–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aroucha, D.C.; do Carmo, R.F.; Moura, P.; Silva, J.L.; Vasconcelos, L.R.; Cavalcanti, M.S.; Muniz, M.T.; Aroucha, M.L.; Siqueira, E.R.; Cahú, G.G.; Pereira, L.M.; Coêlho, M.R. High tumor necrosis factor-α/interleukin-10 ratio is associated with hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Cytokine. 2013, 62, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemon, S.M.; McGivern, D.R. Is hepatitis C virus carcinogenic? Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 1274–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinaldi L, Di Francia R, Coppola N, Guerrera B, Imparato M, Monari C; et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV cirrhosis after viral clearance with direct acting antiviral therapy: Preliminary evidence and possible meanings. WCRJ. 2016, 3, e748. [Google Scholar]

- Valente, G.; Rinaldi, L.; Sgambato, M.; Piai, G. Conversion from twice-daily to once-daily tacrolimus in stable liver transplant patients: Effectiveness in a real-world setting. Transplant Proc. 2013, 45, 1273–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caturano, A.; Galiero, R.; Vetrano, E.; Giorgione, C.; Mormone, A.; Rinaldi, M.; Marfella, R.; Sasso, F.C.; Rinaldi, L. Current hepatocellular carcinoma systemic pharmacological treatment options. WCRJ 2023, e2570. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | |

|---|---|

| Age (yrs.), median [IQR] | 67 [60 – 73] |

| Sex, n (%) Male Female |

165 (53.9) 141 (46.1) |

| BMI, median [IQR] | 26.1 [24.3 – 28] |

| Smoke, n (%) | 2 (0.7) |

| Potus, n (%) | 2 (0.7) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 59 (19.3) |

| Metabolic syndrome, n (%) | 22 (7.2) |

| Number of lesions, n (%) 0 1 ≥2 |

286 (93.5) 15 (4.9) 5 (1.6) |

| Portal invasion, n (%) | 5 (1.6) |

| Bright liver, n (%) | 22 (7.2) |

| Liver stiffness (kPa), median [IQR] | 21 [16 – 29] |

| Duration of therapy, median [IQR] | 12 [12 – 24] |

| Platelets, median [IQR] T0 SVR12 |

108000 [73000 – 153000] 103500 [65250 – 122000] |

| Genotype, n (%) 1 2 3 4 |

243 (79.4) 50 (16.3) 11 (3.6) 2 (0.7) |

| Child-Pugh Score T0, n (%) A B |

289 (94.4) 17 (5.6) |

| Child-Pugh Score SVR12, n (%) A B |

298 (97.4) 8 (2.6) |

| Therapy, n (%) Sofosbuvir Sofosbuvir/Ledipasvir Sofosbuvir/Daclatasvir Sofosbuvir/Simeprevir 3D |

80 (26.1) 69 (22.5) 23 (7.5) 50 (16.3) 84 (27.5) |

| Late HCC, n (%) | 20 (6.5) |

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCC | |||||

| Parameter | Yes (n = 20) | No (n = 286) | P | O.R. [95% C.I.] | p |

| Age (yrs), median [IQR] | 70 [68.2 – 75] | 67 [59.5 – 72] | 0.026 | ||

| Sex, n (%) M/F |

15 (75)/5 (25) |

150 (52.4)/136 (47.6) |

0.050 | ||

| BMI, median [IQR] | 25 [23.2 – 26.7] | 26.2 [24.7 – 28.4] | 0.026 | 0.712 [0.537 – 0.943] | 0.018 |

| Smoke, n (%) | 2 (10) | 0 (-) | 0.000 | ||

| Potus, n (%) | 2 (10) | 0 (-) | 0.000 | ||

| Diabetes, n (%) | 9 (45) | 50 (17.5) | 0.003 | 0.180 [0.045 – 0.713] | 0.015 |

| Metabolic syndrome, n (%) | 3 (15) | 19 (6.6) | 0.162 | ||

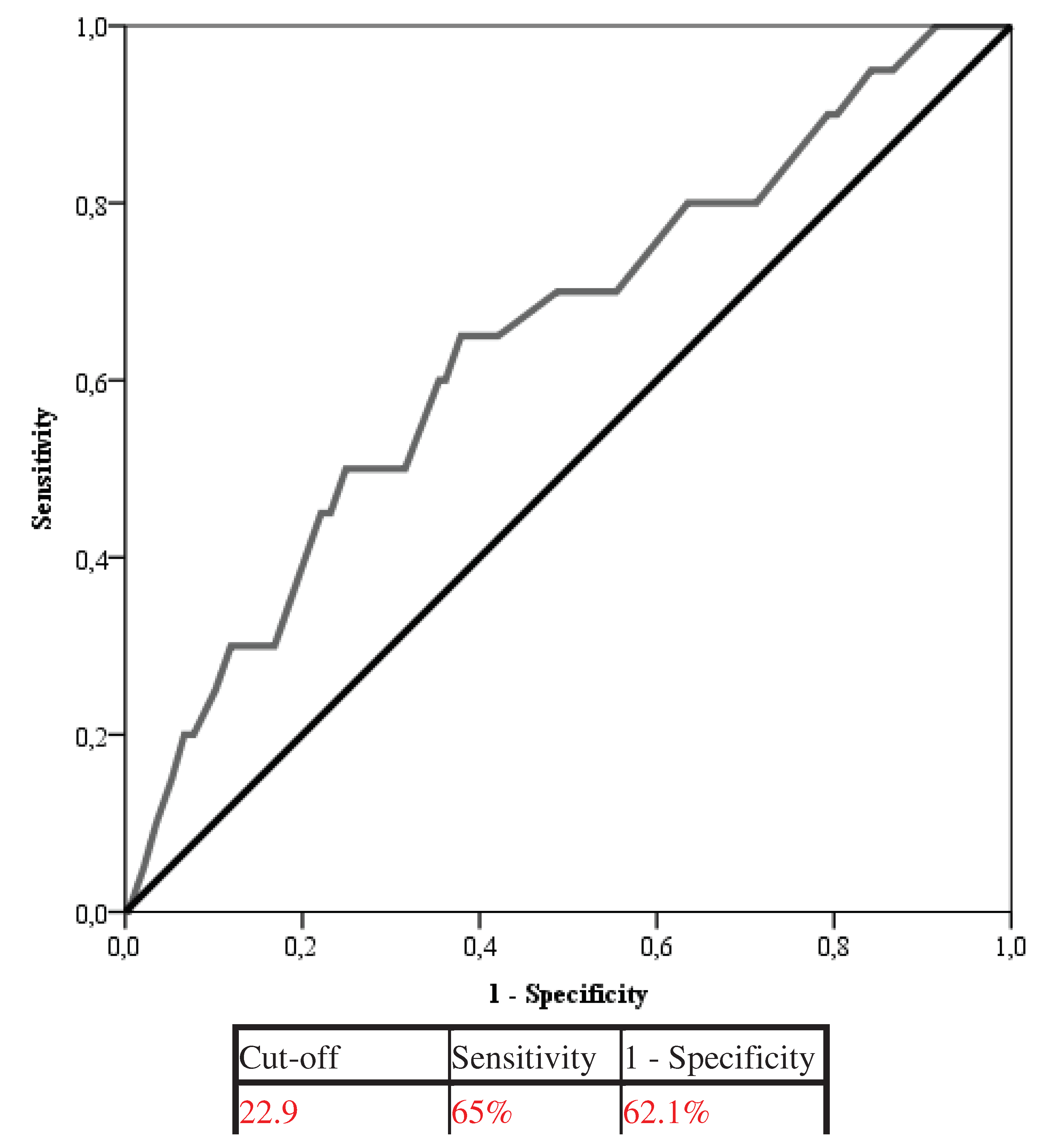

| Liver stiffness (kPa), median [IQR] | 26.5 [18 – 44.5] | 20.4 [16 – 28.7] | 0.028 | 1.070 [1.020 – 1.122] | 0.006 |

| Duration of therapy (months), median [IQR] | 12 [12 – 12] | 12 [12 – 24] | 0.007 | ||

| Platelets, median [IQR] T0 SVR |

75000 [48000 – 109500] n.a. |

115000 [80000 – 166000] n.a. |

0.001 n.a. |

0.975 [0.954 – 0.996] |

0.019 |

| Genotype, n (%) 1 2 3 4 |

15 (75) 3 (15) 1 (5) 1 (5) |

228 (79.7) 47 (16.4) 10 (3.5) 1 (0.3) |

0.095 |

0.007 [0.000 – 0.417] 0.003 [0.000 – 0.280] |

0.017 0.012 |

| Number of lesions, n (%) 0 1 ≥2 |

0 (-) 15 (75) 5 (25) |

286 (100) 0 (-) 0 (-) |

0.000 | ||

| Portal invasion, n (%) | 4 (11.4) | 0 (-) | 0.000 | ||

| Bright liver, n (%) | 1 (5) | 21 (16.8) | 0.172 | ||

| Child-Pugh Score T0, n (%) A B |

15 (75) 5 (25) |

274 (95.8) 12 (4.2) |

0.000 | ||

| Child-Pugh Score SVR12, n (%) A B |

17 (85) 3 (15) |

281 (98.3) 5 (1.7) |

0.000 | ||

| Therapy, n (%) Sofosbuvir Sofosbuvir/Ledipasvir Sofosbuvir/Daclatasvir Sofosbuvir/Simeprevir 3D |

16 (80) 0 (-) 1 (5) 1 (5) 2 (10) |

64 (22.4) 69 (24.1) 22 (7.7) 49 (17.1) 82 (28.7) |

0.000 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).