1. Introduction

The promise of mindfulness interventions in enhancing psychological well-being and other positive outcomes has been recognized worldwide. Mindfulness refers to an individual’s ability to pay attention to the current moment non-judgmentally [

1]. A mindfulness-based stress reduction program (MBSR) was first developed in 1970s and it has become the most well-known program [

1]. Other programs were subsequently developed, such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) [

2], acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) [

3], and dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) [

4].

It is essential to use well-validated and reliable measurements to capture the concept of mindfulness in research studies to ensure credible findings. Thus far, at least eight self-reported questionnaires have been developed. The 14-item Frieburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI) [

5] was originally devised in Germany and was later translated into English [

6]. The 15-item Mindfulness Awareness Attentions scale (MAAS), rooted in the self-regulatory theory, captures the presence or absence of attention and awareness [

7]. The Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness (KIMS) (Baer, Smith & Allen, 2004) contains 39 items and it was developed under the DBT’s concept of mindfulness [

4,

8]. The 12-item Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale Revised (CAMS-R) covers four factors of mindfulness, including attention, awareness, non-judgement, and present focus [

9]. The 13-item Toronto Mindfulness Scale was developed according to Bishop’s concept of mindfulness (TMS) [

10]. The 39-item Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) covers five factors: act with awareness, describing, observing, non-judging, and non-reactivity [

11]. The 16-item Southampton Mindfulness Questionnaire (SMQ) captures four dimensions: decentered awareness of cognitions, letting cognitions pass, allowing one’s attention to remain with difficulty cognition, and accepting difficult thoughts and images [

12]. Lastly, the 20-item Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale (PHLMS) measures two components: acceptance and awareness [

13].

All aforementioned scales have shown sound psychometric properties in previous studies. However, only the MAAS was the focus of this psychometric evaluation study given that the questionnaire’s contents have its root in the mindfulness conceptualization and self-regulatory theory. The scale contains only 15 items, which are simple, short, and easy to administer to people in hospital and community settings. Mindfulness is defined as “enhanced attention to and awareness of current experiences or present reality” [

7] (p. 822). With this definition, they developed the 15-item MAAS with contents to cover the degree to which individuals pay attention to their activities (such as walking, doing jobs/tasks, listening to conversations, driving to places, and eating), notice their emotions and physical tensions, stay focused on present events, forget names, are preoccupied with the past and the future, and run on autopilot mode [

7].

A series of validation studies of the MAAS were conducted across different samples in America [

7]. Firstly, factor analyses suggested a one-factor solution with strong factor loadings. Secondly, convergent and discriminant validity were supported through its correlations with measures of well-being. Thirdly, the MAAS appeared to distinguish mindfulness levels between two groups of adults: meditators and non-meditators. Fourthly, the MAAS was found to predict autonomy and affect among adults and students. Finally, the MAAS was a significant predictor of psychological outcomes in clinical settings across time. Apparently, the aforementioned evidence suggested that the MAAS is a valid and reliable measure of mindfulness for American participants [

7].

According to the principle of cross-cultural psychology, culture plays a crucial role in a person’s development, behavior, and socialization [

14]. Therefore, the concept of mindfulness may not be universal across different countries, contexts, and cultures. To avoid culturally blind issues [

15], it is imperative to ensure that the measures of mindfulness are valid and reliable in different cultures and populations. Thus far, the MAAS has been translated and extended in its use in other languages, including Chinese, French, Norwegian, Spanish, and Thai [

16]. A comparative study examined the MAAS on configural (baseline model), metric (equality of factor loadings), and scalar (equality of intercepts) invariances across American and Thai university students [

16]. The results supported the equivalence of all factor loadings and some intercepts across the two subgroups. Other studies documented that the Chinese, French, Spanish, and Swedish versions of the MAAS had adequate psychometric properties with a unidimensional structure [

17,

18,

19,

20].

Mindfulness interventions have been implemented in some Asian countries, including Thailand and the Philippines. There is a need to further conduct the validation study of the MAAS on Asian samples given the limited research in the literature. Furthermore, most previous studies examined the scale on cross-sectional samples; thus, it is unclear if the results maintained across time. Therefore, this study aimed to (a) initially examine a factorial structure of the MAAS among Thai secondary school students and (b) test whether the psychometric properties (construct validity, concurrent validity, and reliability) remain stable across two repeated cross-sectional samples among youths in Thailand and in the Philippines.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Participants

A descriptive correlational research was conducted in two countries (Thailand and the Philippines), and five data sets were collected (Sample A, B1, B2, C1, and C2). Conventionally, the sample size estimation for CFA was based on the observations-estimated parameter ratio whereby the 5:1 ratio would be acceptable [

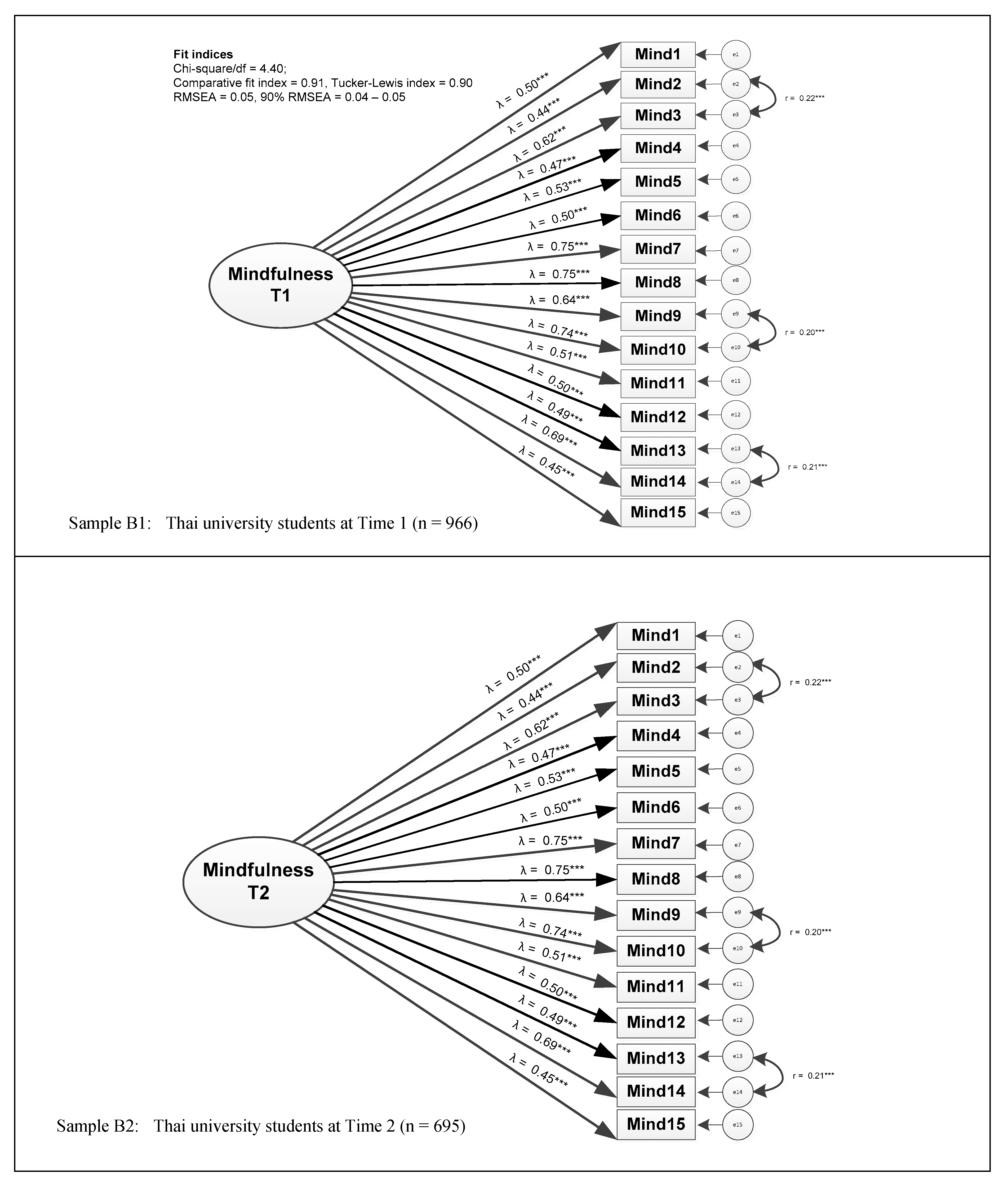

21]. Given the 30 parameters (15 factor loadings and 15 variances) (

Figure 1), the minimal adequate sample size would be 150 students for each data set.

Sample A was a convenient sample of students who were recruited from three different secondary schools in Thailand. One school contained only male students, one had only female students, and one contained both male and female students (mixed sample). This data collection commenced after receiving ethics approval from the study university. The researchers liaised with school principals to arrange out-of-class meetings with the students to explain the study, distribute participant information sheets (PIS), and request their involvement. The students were then advised to discuss with their parents. Interested students and their parents were asked to sign consent and assent forms respectively and to complete self-reported paper-and-pencil questionnaires.

Sample B1 and Sample B2 were two repeated cross-sectional samples. They involved undergraduate university students from a public university in Thailand. Upon approval from the university ethic committee (IRB), the researchers sought permission from deans of all faculties to recruit participants. Then, we began recruiting participants by organizing meetings with students and distributing personal information sheets (PIS). Interested participants each signed a consent form and completed a self-reported paper-and-pencil questionnaire (Sample B1). One year later, we recruited another sample (Sample B2) using the same data collection process.

Sample C1 and C2 were two repeated cross-sectional samples. They encompassed undergraduate students at a university in the Philippines. Following ethics approval, the researchers sought permission from university administrative personal to conduct the study. Following permission, we e-mailed a letter of invitation to all students during their academic year (Sample C1). Each interested participant was asked to visit the study website, sign an online consent form, and complete an online questionnaire. One year later, we recruited another sample (Sample C2) using the same data collection process.

2.2. Measurements

Data were collected using paper-and-pencil questionnaires (Sample A, B1, and B2) and online questionnaires (Sample C1 and C2). Demographic variables were collected, including each student’s age, gender, religion, and satisfaction with his/her family income. The 15-item MAAS was devised to measure trait mindfulness [

7]. Students were asked to identify their experiences on a six-point scale, ranging from one (almost always) to six (almost never). Scores for all items were reverse-coded, in that the highest score signified the highest level of mindfulness. The Thai version of the MAAS was administered on Samples A, B1, and B2 whereas the English version was used in Samples C1 and C2.

Psychological well-being was measured with the 18-item Psychological Well-Being Scale (PWBS) [

22]. Researchers translated and back-translated the Thai version of the PWBS using Brisline’s method [

23]. Three nurse educators with research experience reviewed the Thai and English versions of the PWBS to ascertain the meanings of the questionnaire items. Factor analyses in a previous study revealed two distinct factors of the PWBS: the autonomy and growth factor and the negative triad factor [

24]. The Cronbach’s alpha values of the former were 0.81 to 0.85 and the latter were 0.56 to 0.74, respectively [

24]. The PWBS served as an external measure for testing the concurrent validity of the MAAS.

2.3. Data Analyses

Univariate analyses were performed to describe samples and study variables. A severe non-normal distribution would be observed if its skewness was larger than two and its kurtosis was larger than seven for samples larger than 300 [

25]. To explore the factor structure of the MAAS on Sample A, exploratory factor analyses (EFA) were performed using principal axis factoring as an extraction method and different rotation methods, including Varimax and Oblimin. To determine the number of factors to extract, we used the following criteria: parsimony, interpretability of the extracted factor, content validity, and previous evidence [

26]. We also examined statistical parameters including eigenvalue and scree plots. A factor loading of 0.30 or higher was used to determine a sufficient relationship between each item and its underlying factor [

27].

The results from the EFA were then submitted to confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) using IBM SPSS AMOS version 25.0. Model fit was examined via a) chi-square per degree of freedom (χ

2/df) < 5 [

28], b) confirmatory fit index (CFI), Tucker-Luwis Index (TLI) > 0.90 as acceptable fit and > 0.95 as well-fit, and c) root mean square of error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.05 as well-fit and < 0.08 as reasonable fit [29─31]. Regarding the measurement invariance across samples, we first determined the baseline model of each sample separately. Then, we performed multiple-group CFA using the available features in AMOS [

29] For Model 1, we ran the analyses and allowed all parameters to be freely estimated without any equality constraints (Baseline model). For Model 2, we imposed quality constraints on all factor loadings across two samples. For Model 3, all covariances were imposed to be equal, while Model 4 imposed equality constraints on measurement residuals. The measurement invariance (equivalence) would be assumed if there was no significant decrease in model fit (in comparison with Model 1), evidenced by insignificant Δχ

2 (p > 0.05) and ΔCFI < 0.01 [

29,

32].

Concurrent validity was estimated using IBM SPSS. Pearson product moment correlations were used to determine relationships between the MAAS and the two-factor PWBS. If the MAAS items really captured the construct of mindfulness, they would exhibit positive correlations with the autonomy and growth factor and negative correlations with the negative triad factor of the PWBS. Correlation coefficients of 0.10, 0.30, and 0.50 would be regarded as weak, moderate, and strong, respectively [

33]. The internal consistency reliability of the MAAS was then estimated using a reliability analysis. Cronbach’s alpha values (α) greater than 0.70 would signify an acceptable reliability [

34].

2.4. Ethical Consideration

This research was reviewed and received approval from two Institution Review Boards (IRBs). The IRB in Thailand approved the study conducted in secondary schools and university in Thailand. The IRB in the Philippines approved the study conducted in university in the Philippines. All participants received written information concerning the research project and signed the informed consent form prior to completing the self-reported questionnaires. The researchers also emphasized the issues of voluntary participation and confidentiality.

3. Results

3.1. Participants Characteristics

Table 1 displays characteristics of the study participants in Samples A (n = 624), B1 (n = 966), B2 (n = 695), C1 (n = 221), and C2 (n = 409). Most students were female across the five samples. An average age was 16.14 years (SD = 0.97) for Sample A. Those numbers were in the range of 19.56 to 20.34 years for the other samples (SD ranging from 1.43 to 1.76).

3.2. Exploratory Factor Analyses (EFA): Sample A

We conducted EFA on Sample A (n = 624) to initially explore the factorial structure of the Thai-version MAAS. To compare findings across schools, we subsequently examined the factorial structure on the three subsamples, including Subsample A1 (male school, n = 194), Subsample A2 (female school, n = 231), and Subsample A3 (mixed-gender school, n = 199). The results suggested that the MAAS had one factor for the total sample and three schools (

Table 2). This accounted for 28.16% of the variance on questionnaire items and all items had sufficient factor loadings (λ > 0.30). For the total sample and three schools, items 7, 8, 9, 10, and 14 had the strongest factor loadings. Internal consistency reliability was good for the total sample and the three schools (Cronbach’s alphas were in the range of 0.84 to 0.86). All evidence in this section supported the single dimension of the Thai version of the MAAS.

3.3. Measurement Invariance across Samples: Samples B1 and B2

Given the results of EFA on Sample A, we performed CFA on Thai university students (Sample B1and B2) separately and simultaneously. We submitted the one-factor structure of the MAAS into AMOS and tested for measurement invariance across samples. The results of the modification indices suggested that three pairs of error variances (Mind 2-Mind 3, Mind 9-Mind10, and Mind 13-Mind14) were correlated. We carefully examined the contents of each pair and found that the contents were overlapped to some degree. Hence, we allowed correlations among the variances. As an example, Mind 2 (Break or spill things because of carelessness, not paying attention, or mind wandering) and Mind 3 (Difficult to stay focused on situations in the present moment) contained similar information (

Figure 1).

The findings (

Table 2) indicated that Model 1 (with no equality constraints between Sample B1 and Sample B2) had an adequate fit with the sample data (χ

2/df = 5.03, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.05, 90% RMSEA = 0.46, 0.53). However, after imposing quality constraints, Models 2, 3, and 4 did not have significant reductions in fit indices. Therefore, we can conclude that: a) the MAAS has a one-factor structure and b) all parameters (factor loadings, covariances, and residuals) were invariant across the two samples. Furthermore,

Figure 1 showed that all factor loadings achieved statistical significance and Items 7, 8, 9, 10, and 14 had the strongest factor loadings (

Figure 1).

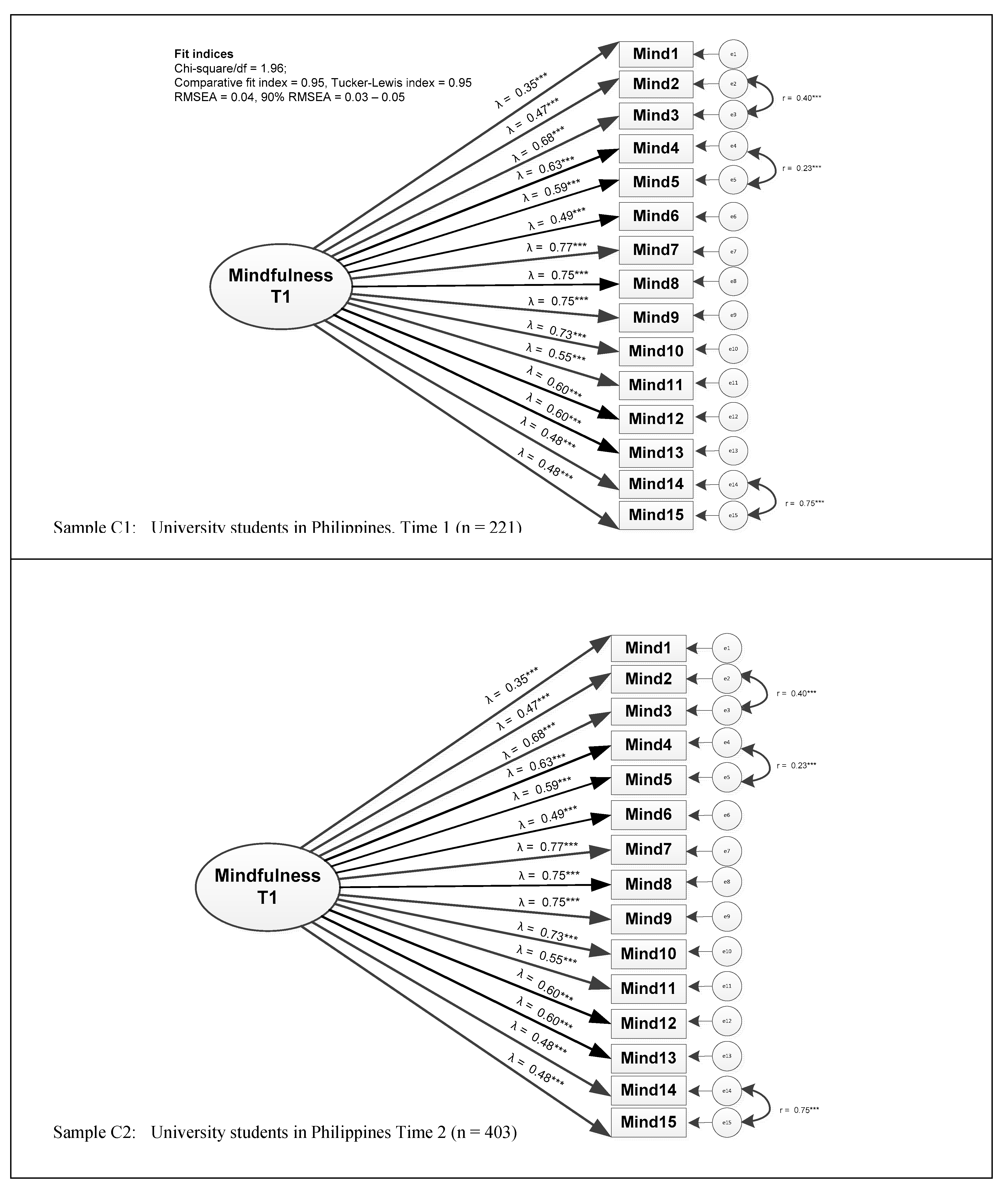

3.4. Measurement Invariance across Samples: Samples C1 and C2

For these analyses, we submitted a single-factor structure of the English version of the MAAS into AMOS to test measurement invariance across samples on university students in the Philippines. After viewing the modification indices output, three pairs of variances were suggested to be correlated. This included Mind 2-Mind 3 (pair 1), Mind 4-Mind 5 (pair 2), and Mind 14-Mind 15 (pair 3). Given that the contents of each pair were similar, we allowed the variance correlations (

Figure 2).

Additional results suggested that Model 1 (with no equality constraints between Sample C1 and Sample C2) fit reasonably well with the sample data (χ

2/df = 2.17, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.04, 90% RMSEA = 0.04, 0.05) (

Table 2). Nevertheless, Models 2, 3, and 4 did not have significant reductions in fit indices. Therefore, we can conclude that a) the MAAS has a one-factor structure and b) all parameters (factor loadings, covariance, and residuals) were invariant across sample C1 and C2. In addition, all factor loadings achieved statistical significance and Items 7, 8, 9, and 10 had the strongest factor loadings (

Figure 2).

3.5. Concurrent Validity

Table 3 illustrates the correlation between the MAAS and the PWBS across samples. All correlation coefficients achieved statistical significance (p < 0.01). As anticipated, the English version of the MAAS was positively correlated with the autonomy and growth factor (Sample C1, r = 0.38, p < 0.01; Sample C2, r = 0.34, p < 0.01) and negatively correlated with the negative triad factor (Sample C1, r = -0.48 p < 0.01; Sample C2, r = -0.40, p < 0.01).

Similarly, the Thai version of the MAAS was positively associated with the autonomy and growth factor (Sample B1, r = 0.43, p < 0.01; Sample B2, r = 0.41, p < 0.01) and negatively associated with the negative triad factor (Sample B1, r = -0.41, p < 0.01; Sample B2, r = -0.50, p < 0.01). This information supported the concurrent validity of the English and Thai versions of the MAAS across the two repeated cross-sectional samples.

3.6. Internal Consistency Reliability

The MAAS had acceptable internal consistency reliability for all samples. Specifically, Sample B1 and Sample B2 had Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.88 and 0.86, respectively (

Table 3). Additionally, Sample C1 and Sample C2 had Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.90 and 0.89, respectively (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to test the psychometric properties of the 15-item MAAS on five data sets of Thai and Filipino youths. Three samples (A, B1, and B2) used the Thai version of the MAAS whereas two samples (C1 and C2) utilized the English version of the MAAS. For all five samples, the findings consistently supported the unidimensional structure of MAAS and all questionnaire items had sufficient factor loadings. This information suggested that all items were suitable to capture the underlying concept of mindfulness. Moreover, statistical parameters demonstrated invariant characteristics (equality) across two repeated cross-sectional samples for both Thai and Filipino participants. The evidence in this study provided strong support for the construct validity of the Thai and English versions of the MAAS. Previous studies also reported the unidimensional structure of the MAAS among American, Thai, Colombian, and Spanish undergraduate students (7,16,20,35) and French high school students and community participants [

19]. Another study conducted a cross-cultural validation and found configural, metric, and scalar invariances between Thai and American samples [

16].

For all five samples, items 7, 8, 9, and 10 showed the strongest factor loadings, suggesting that they were the best items to capture the concept of mindfulness. Item 14 was one of the strongest items for only three samples (A, B1, and B2). The factor loadings of the five items ranged from 0.60 to 0.77 across all samples. Item 7 states how a person runs on autopilot without awareness of his/her current actions and item 8 addresses rushing through activities without paying attention. item 9 mentions focusing on the goals but losing touch with the current actions and item 10 indicates how an individual does a job automatically without awareness. Additionally, item 14 states doing things without paying attention. The above-mentioned items reflect the conceptual definition of mindfulness provided by [

1,

7]. Specifically, Kabat-Zin (1994) originally defined mindfulness as paying cautious attention to the present moment non-judgmentally, while Brown and Ryan (2003) viewed mindfulness as enhanced attention and awareness to the present reality [

7]. Our findings concurred with those in previous research whereby items 7, 8, 9, 10, and 14 had the strongest factor loadings among undergraduate students in America with factor loadings that ranged from 0.71 to 0.78 for the total sample and male/female subgroups [

35]. A study in Norway tested the short-version of the MAAS, which contained only Items 7, 8, 9, 10, and 14, and reported that the five-item MAAS was an adequate instrument of mindfulness in Norwegian adolescent samples [

36].

The concept of mindfulness appears to be associated with psychological well-being. Brown and Ryan (2003) proposed four mechanisms underlying the link between mindfulness and an individual’s well-being [

7]. First of all, the vividness of one’s current experience minimizes autonomic thoughts, habits, and unhealthy behaviors. Secondly, attention engages people in gathering information associated with healthy behaviors. Thirdly, attention is a key role in a healthy regulatory process. Finally, mindfulness enhances the quality, enjoyment, and flowed activities of the current experiences. In line with the conceptualization and mechanisms, our findings suggested that the Thai and English versions of the MAAS had significant moderate relationships with measures of psychological well-being (the autonomy and growth factor and the negative triad factor) across two assessment points. This evidence then supported the concurrent validity of the scale. Our results were comparable with other studies. Using the English version of the MAAS, Brown et al. (2011) documented significant correlations between the scale and several measures of well-being, including negative affect, positive affect, life satisfaction, substance-use coping, and healthy self-regulation [

37]. The French version of the MAAS appeared to link with depression and cognitive emotion regulations [

19]. The Spanish version of the MAAS was found to be negatively associated with measures of stress, depression, and anxiety and positively correlated with life satisfaction [

20].

This study has strengths concerning the use of five data sets with a large sample size. Five data sets were collected, and the findings confirmed the psychometric properties of the MAAS. Two languages (Thai and English) and two data collection methods (paper-and-pencil and online questionnaires) were used, which might have increased the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, correlations between the scale and other measures were tested. Nevertheless, there were a few limitations, in that we tested the psychometric properties on convenient healthy samples; thus, the findings might not be applicable to people with clinical conditions. Furthermore, we used only self-reported questionnaires, which hampered the possibility to perform a multitrait-multimethod matrix to test the convergent and divergent validity of the MAAS.

5. Conclusions

The evidence in this study provided strong support for the construct validity, concurrent validity, and reliability of the Thai and English versions of the MAAS. The Thai version of the MAAS may be appropriate for assessing mindfulness among Thai young participants and the English version of the MAAS may be suitable for youths in the Philippines and other countries. The scale can be used in experimental research for measuring changes in pre- and post-mindfulness interventions.

Mindfulness interventions have been implemented for diverse populations around the world to minimize stress and maximize psychological outcomes (such as psychological well-being). There is a need to measure changes in mindfulness before and after the mindfulness interventions to confirm the effectiveness of the interventions. Nevertheless, the evidence to support psychometric properties of the MAAS among Asian populations is lacking. This study provides solid evidence to support construct validity, concurrent validity and reliability of the MAAS across two languages (English and Thai) two formats (paper-and-pencil versus online questionnaires) and five samples (The Philippines and Thai).

Author Contributions

“P.K.Y, W.T. and N. V., Conceptualization; Methodology; Project administration; Formal analysis; Writing—original draft preparation, Writing—review and editing. D.R., Z.F., J.S. Methodology; writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research had no fundings.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by two Institutional Review Boards (IRBs). The IRB in Thailand approved the study conducted in secondary schools and university in Thailand. The IRB in the Philippines approved the study conducted in university in the Philippines.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Public Involvement Statement

No public involvement in any aspect of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life.; Hyperion: New York, US, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, Z. V. , Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, US, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S. , Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change; Guilford Press: New York, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan, M. M. Cognitive-Behavioural Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder; Guilford Press: New York, US, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Buchheld, N., Grossman, P., & Walach, H. Measuring mindfulness in insight meditation (vipassana) and meditation-based psychotherapy: the development of the Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI). Journal for Meditation and Meditation Research 2001, 1, 11–34.

- Walach, H., Buchheld, N., Buttenmüller, V., Kleinknecht, N., & Schmidt, S. Measuring mindfulness--The Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI). Personality and Individual Differences 2006, 40, 1543-1555. [CrossRef]

- Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2003, 84, 822-848. [CrossRef]

- Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., & Allen, K. B. (2004). Assessment of mindfulness by self-report: The Kentucky Inventory of mindfulness Skills. Assessment 2004, 11, 191-206. [CrossRef]

- Feldman, G., Hayes, A., Kumar, S., Greeson, J., & Laurenceau, J.-P. Mindfulness and emotion regulation: The development and initial validation of the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised (CMS-R). Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 2007, 29, 177-190. [CrossRef]

- Lau, M. A., Bishop, S. R., Segal, Z. V., Buis, T., Anderson, N. D., Carlson, L., Shapiro, S., & Carmody, J. The Toronto mindfulness scale: Development and validation. Journal of Clinical Psychology 2006, 62, 1445–1467. [CrossRef]

- Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. Using Self-Report Assessment Methods to Explore Facets of Mindfulness. Assessment 2006, 13, 27-45. [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, P., Hember, M., Mead, S., Lilley, B., & Dagnan, D. Responding mindfully to unpleasant thoughts and images: Reliability and validity of the Southampton Mindfulness Questionnaire (SMQ). Unpublished manuscript, University of Southampton Royal South Hants Hospital, UK, 2007.

- Cardaciotto, L., Herbert, J. D., Forman, E. M., Moitra, e., & Farrow, V. The assessment of present-moment awareness and acceptance: The Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale. Assessment 2008, 15, 204-23. [CrossRef]

- Berry, J. W. , Poortinga, Y. H., Segall, M. H., & Dasen, P. Cross-cultural psychology, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, Engliand, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Scholten, S., Velten, J., Bieda, A., Zhang, X. C., & Margraf, J. Testing measurement invariance of the depression, anxiety, and stress scale (DASS-21) across four countries. Psychological Assessment 2017, 29, 1376-1390. [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M. S., Charoensuk, S., Gibert, B. D., Neary, T. J., & Pearc, K. L. (2009). Mindfulness in Thailand and the United States: A case of apples and oranges? Journal of Clinical Psychology 2009, 65, 590-612. [CrossRef]

- Black, D. S., Sussman, S., Johnson, A., & Milam, J. Psychometric assessment of the mindfulness attention awareness scale (MAAS) among Chinese Adolescents. Assessment 2012, 19, 42-52. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E., Lundh, L., Homman, A., & Wanby-Lundh, M. Measuring mindfulness: Pilot studies with the Swedish versions of the mindful attention awareness scale and the Kentucky inventory of mindfulness skills. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy 2009, 38, 2-15. [CrossRef]

- Jermann, F., Billieux, J., Laroi, F., Argembeau, A., Bondolfi, G., Zermatten, A., & Linden, M.V. Mindful attention awareness scale (MAAS): Psychometric properties of the French translation and exploration of its relations with emotion regulation strategies. Psychological Assessment 2009, 21, 506-514. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, F. J., Suarez-Falcon, J. C., & Riano-Hernandez, D. Psychometric properties of the mindful attention awareness scale in Colombian undergraduates. Suma Psicologica 2016, 23, 18-24. [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. & Chou, C. Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological Methods and Research 1987, 16, 78–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D. In the eye of the beholder: Views of psychological well-being among middle-aged and older adults. Psychology and Aging 1989, 4, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. W. The wording and translation of research instruments. In Field methods in cross-cultural research cross-cultural research and methodology series; W. L. Lonner, W.L. & Berry, J.W., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, US 1986; Volume 8, pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Klainin-Yobas, P., Thanoi, W., Vongsirimas, N., & Lau, Y. Evaluating the factor structure of the psychological well-being scale among students across Thai and Singaporean samples. Psychology 2020, 11, 71-86.

- Kim H. Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics 2013, 38, 52. [CrossRef]

- Fabrigar, L. R. , MacCallum, R. C., Wegener, D. T., & Strahan, E. J. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Method 1999, 4, 272–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B. G. & Fidell, L. S. Using multivariate statistics. Allyn & Bacon: Needham Heights, MA, US, 2001.

- Schumacker, R. E. , & Lomax, R. G. A beginner's guide to structural equation modeling, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, US, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B. M. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, US, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling 1999, 6, 1–55. [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H. W., Hau, K-T., & Wen, Z. In search of golden rules: comment on hypothesis testing approaches to setting cut off values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler's findings. Structural Equation Modeling 1999, 11, 320-341. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F. F. Sensitivity of Goodness of Fit Indexes to Lack of Measurement Invariance. Structural Equation Modeling 2007, 14, 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, L. S., Gamst, G., & Guarino, A. J. Applied multivariate research: design and interpretation (2nd ed.). Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, US, 2013.

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297-334. [CrossRef]

- Mackillop, J., & Anderson, E. J. Further psychometric validation of the mindful attention awareness scale (MAAS). Journal of Psychopathological Behavioural Assessment 2007, 29, 289-293.

- Smith, O. R. F, Melkevik, O. , Samdal, O, Larsen, T. M., & Haug, E. Psychometric properties of the five-item version of the Mindful Awareness Attention Scale (MAAS) in Norwegian adolescents. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 2017, 45, 373-380. [CrossRef]

- Brown, K. W., West, A. M., Loverich, T. M., & Biegel, G. M. Assessing adolescent mindfulness: Validation of an adapted mindful attention awareness scale in adolescents normative and psychiatric population. Psychological Assessment 2011, 23, 1023-1033. [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R. C., K. F. Widaman, et al. "Sample size in factor analysis. Psychological Methods 1999, 4, 84-89. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).