Introduction

T2D is the most prevalent metabolic disease and a significant public health concern (Liu et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2016), leading to early-onset disability and elevated mortality due to various complications (Cousin et al., 2022). Between 1990 and 2017, the global trend for age-standardized rates of T2D, as measured by the number of cases per 100,000 population, showed a significant increase. Specifically, incidence rose from 228.5 (213.7–244.3) to 279.1 (256.6–304.3), prevalence climbed from 4576.7 (4238.6–4941.9) to 5722.1 (5238.2–6291.0), and mortality increased from 10 (9.5 -10.6) to 13.2 (12.7-13.7). Additionally, disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) grew from 553.6 (435.1-696.5) to 709.6 (557.2-888.3) (Lin et al., 2020). Although the rise in T2D is attributed to a complex interplay between environmental factors, genetic elements predisposing to an increased risk of T2D have also been identified (Prasad & Groop, 2015).

The prevalence of T2D varies widely between populations, from a small percentage among Caucasians in Europe to more than 50% among the Pima community in Arizona. While some of the observed ethnic variability could be attributed to environmental and cultural factors, some variation depends on genetic differences (Prasad & Groop, 2015). Another important hallmark of T2DM is that it is more frequently diagnosed at lower ages and body mass index in male cases, and related to obesity, it is more common in female patients (Cooper et al., 2021; Kautzky-Willer et al., 2016).

Insulin resistance diabetes heritability in families is well established, and the risk of developing depends on genetic and environmental factors. However, heritability estimates have varied between 25% and 80% in different studies; the highest estimates are seen in those studies with the most extended follow-up periods, and the exact mechanism of transmission from parents to children has not been precisely established (Ahmad et al., 2022; Langenberg & Lotta, 2018; Prasad & Groop, 2015). The lifetime risk of developing T2D is 40% for people with a parent with T2D and nearly 70% if both parents are affected (Prasad & Groop, 2015). Furthermore, the T2D concordance rate in monozygotic twins is around 70%, while the concordance in dizygotic twins is only 20% to 30%. Proband concordance rates for monozygotic twins range from 34% to 100% (Prasad & Groop, 2015). The relative risk for first-degree relatives, the risk of developing T2D if they have an affected parent or sibling compared to the general population, is approximately three and ~6 if both parents are affected. However, these figures vary according to the cohort and population studied (Prasad & Groop, 2015).

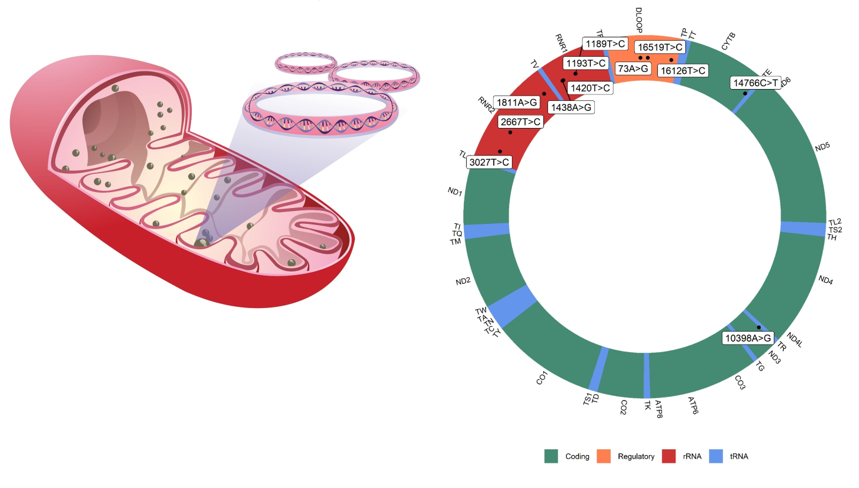

In recent years, mitochondrial genome polymorphisms have been the target of study in the pathogenesis and progression of different chronic metabolic diseases (Kronenberg & Eckardt, 2022; J. Li et al., 2019; Martín-Jiménez et al., 2020; Swan et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2018). Although mitochondria can be storaged from 2 to 10 molecules of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) (Lightowlers et al., 1997), the absence of histones favors a higher rate of mutation (between 6 and 17 times) than nuclear DNA (Naue et al., 2015). In addition, this allows the number of mitochondria and the genetic content of the mitochondria to vary between the cell tissues of the same person. Due to this, the presence of mtDNA mutations in the tissues that participate in the regulation of metabolism can contribute to dysfunction and, therefore, to the development of metabolic diseases (Fex et al., 2018; Kwak et al., 2010; Weksler-Zangen, 2022). Thus, it has been reported that mitochondrial metabolism is involved in the processes that control insulin release from pancreatic β cells (Mulder, 2017), and its dysfunction due to mutations in the mtDNA would favor the development of diabetes (Guo et al., 2005; C. Li et al., 2022; Liao et al., 2008; Sikhayeva et al., 2017). On the other hand, it has been reported that the presence of mutations in the mtDNA of insulin target tissues (like myocytes), and consequently mitochondrial dysfunction, plays a highly debated role in the development of diabetes (Dela & Helge, 2013; Hesselink et al., 2016).

The single nucleotide genetic variants in mitochondrial DNA could be associated with the risk of developing T2D (Guo et al., 2005). Although, the exact molecular mechanisms through which this would occur remain largely unknown and the subject of debate. Likewise, the polymorphisms identified in some populations need to be validated in larger populations and with the inclusion of multiple ethnic groups (Floris et al., 2020). Therefore, the present study aimed to determine if mitochondrial polymorphisms previously identified in the literature are associated with susceptibility to T2D using a multiethnic population.

Insulin resistance is essential for developing T2D and is present in most individuals with carbohydrate metabolism disorders before developing clinical manifestations that can be classified, according to current criteria, as T2D. This most important metabolic problem has hereditary determinants that are not well established so far, as well as environmental determinants focused on energy storage and metabolism, recent knowledge from genomic analysis in humans, together with in vivo and ex vivo metabolic studies in cell and animal models, have evidenced the critical importance of the role of reduced mitochondrial function as a predisposing condition for insulin resistance ((Chen & Gerszten, 2020). These studies support the hypothesis that reduced mitochondrial function, particularly in insulin-responsive cells such as skeletal muscle fibers, adipocytes, and hepatocytes, is inextricably linked to insulin resistance through effects on the insulin balance of cellular energy (Sangwung et al., 2020). In the setting of the diabetic patient, basal insulin secretion is increased. However, after a certain time, pancreatic beta cells fail to compensate for this abnormality, leading to clinical hyperglycemia, with skeletal muscle accounting for most insulin-stimulated glucose disposal, and consequently, it is the predominant insulin resistance site in T2D (Højlund et al., 2008; Højlund & Beck-Nielsen, 2006a).

Besides carbohydrate metabolism, Mitochondria use lipids for energy production, and decreased mitochondrial function is associated with ectopic adipose tissue and insulin resistance (Højlund et al., 2008). Resting adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis in skeletal muscle in insulin-resistant subjects is reduced compared with insulin-sensitive individuals, suggesting a contribution of mitochondrial dysfunction to insulin resistance (Morino et al., 2006; Petersen et al., 2003).

Previous studies have suggested an association between decreased muscle oxidative capacity and insulin resistance in T2D and obesity. Thus, muscle citrate synthase correlates strongly with its mitochondrial content, oxidative capacity, and reduced maximal oxygen consumption in T2D (Kelley et al., 2002; Kruszynska et al., 1998). Furthermore, studies of key metabolic enzymes in muscle have shown an increased ratio of glycolytic capacity relative to mitochondrial oxidative capacity in patients who have T2D and a significant correlation between the ratio of glycolytic to oxidative enzyme capacity and insulin resistance (Højlund & Beck-Nielsen, 2006a).

Mitochondria in skeletal muscle from patients who have T2D are minor and show altered morphology (He et al., 2001; Kelley et al., 2002). The reduction in mitochondrial function in patients with type 2 diabetes is accompanied by an increase in intracellular lipid concentration in skeletal muscle tissue, a reduction in mitochondrial density/content, and a decrease in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation rates (Befroy et al., 2007; Morino et al., 2005; Petersen et al., 2004).

Most evidence and published studies focus on the association of mitochondrial alterations with insulin resistance, both in its number per cell and metabolism. A decrease in mitochondria number and electron transport chain activity in T2D and obese patients compared to lean volunteers has been previously documented (Kelley et al., 2002; Ritov et al., 2005), as well as impaired mitochondrial function in skeletal muscle obtained from obese type 2 diabetics (Mogensen et al., 2007). A lack of response of muscle mitochondrial ATP production to high-dose insulin infusion has also been reported in type 2 diabetic subjects, suggesting an impaired response to insulin and reduced mitochondrial function (Asmann et al., 2006; Stump et al., 2003); a modest decrease in mitochondrial ATP synthesis rates in non-obese T2D patients and older non-diabetic individuals compared with younger non-diabetic groups under fasting conditions and after insulin stimulation (Szendroedi et al., 2007) and the reduced basal ADP-stimulated and intrinsic mitochondrial respiratory capacity in type 2 diabetic subjects compared to control subjects matched for age and BMI (Phielix et al., 2008; Schrauwen & Hesselink, 2004; Schrauwen-Hinderling et al., 2007). However, some authors attribute the reduced mitochondrial capacity per unit mass skeletal muscle observed in T2D patients to the concept of reduced mitochondrial content and volume, oxidative enzymes levels, mtDNA, and decreased levels of co-regulators of mitochondrial biogenesis (Boushel et al., 2007). Transcriptomic evidence of altered mitochondrial biogenesis and proteomic alterations of mitochondrial dysfunction (Hittel et al., 2005; Højlund et al., 2003; Ptitsyn et al., 2006) does not entirely exclude the possibility of primary defects in mitochondrial function in human skeletal muscle and no evidence so far demonstrates a cause-and-effect relationship between insulin resistance, and T2D (Højlund & Beck-Nielsen, 2006b).

The polymorphism m.16189T>C (rs386828865) near the segment associated with the termination in the non-coding region of mtDNA in the hypervariable region (HVR1) of mtDNA has a correlation with insulin resistance and with the prevalence of T2D reported mainly in Asian populations 28.8% and 37% in Koreans and Japanese, respectively; on the other hand, a wide variation was observed, from 10% in Alorese populations to 60% in Nia’s populations and between 10% and 15% in Caucasians and a frequency of (Kwak & Park, 2016; Sudoyo et al., 2003).

The fact that the point mutation m.16189T>C can be significantly associated with diabetes in populations of Caucasian, Asian, and Chinese origin suggests that this single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) probably plays a direct role in predisposition to T2D. However, there is increasing evidence that the generation or expression of pathological mtDNA mutations could be influenced by other SNPs in the mtDNA, for example, the mtDNA mutation m. 11778G>A for LHON, the mtDNA mutation m.1555A>G underlying sensorineural deafness inherited from the mother, and the additional mutation, m14709T>C in tRNAglu firmly classified as a causal mutation (Sudoyo et al., 2003).

The m.16189T>C polymorphism is near the termination-associated segment in the non-coding mtDNA region associated with an uninterrupted cytosine tract. The tract varies in length between 5 and 13 consecutive cytokines; the wild-type genome contains nine cytokines with intermediate thymine at position m.16189 after the fifth cytokine. The m.16189T>C polymorphism decreases the mtDNA replication rate and causes a lower number of mtDNA copies and a disadvantage in metabolic efficiency. The m.16189T>C is a brake on the replication slippage or facilitates the entire process. The m.16189T>C polymorphism is associated with a maternal BMI below 18, low birth weight, a higher body mass index during adulthood, and a higher frequency of type 2 diabetes in individuals in UK population studies. UK and Asia (Soini et al., 2012).

This study’s purpose and primary objective was to identify the frequency of mtDNA polymorphisms in patients with and without T2D and their potential association with the disease.

Material and methods

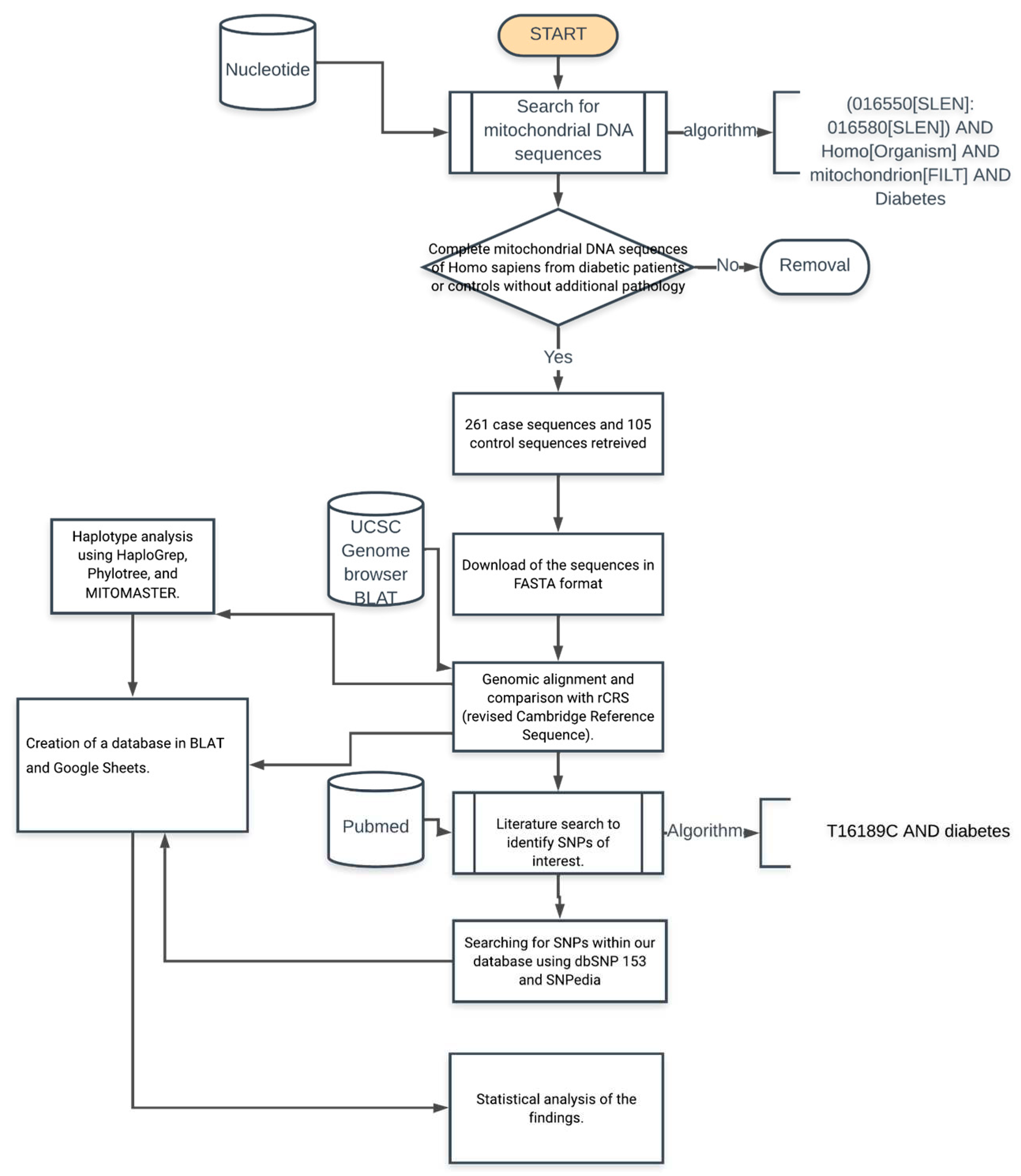

An analytical cross-sectional study was conducted based on complete mitochondrial genome sequences in the NCBI Nucleotide database (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore). To identify the sequences, we use booleans and keywords in the search string: (Homo[Organism] OR Homo sapiens[organism]) AND mitochondrion[FILT] AND (015400[SLEN]:016700[SLEN]) AND ("Type 2 diabetes" OR "non-insulin-dependent diabetes" OR diabetes OR T2D), to select complete mitochondrial sequences we filtered those only complete chromosome mitochondrial sequences.

Once the sequences were identified in the database, the metadata associated with each of them was explored to validate the place of origin; the following was required as inclusion criteria: (1) sequence length of 16569+/-10 bp, (2) Homo sapiens species tag, (3) type 2 diabetes diagnostic tag or defined as non-insulin dependent, (4) tag of origin of the sequence as a control grade individual in a study published on type 2 diabetes or defined as non-insulin dependent and (5) reference citation of the article associated with the study of the origin of the sequence, eliminating all those who did not meet any inclusion criteria.

For identification of haplogroups and polymorphisms of the selected sequences using the

Genebank sequence number, the haplotype was determined, and polymorphisms identified using MITOMASTER (

https://www.mitomap.org/foswiki/bin/view/MITOMASTER), from which a database was built with the identified polymorphisms. The criteria for classifying the different haplogroups can be found in more detail in the Phylotree database (

http://www.phylotree.org/) (Lott et al., 2013; van Oven & Kayser, 2009). In addition, for the construction of the database, the alignment of the sequences was carried out in the genomic browser UCSC Genome Browser (

https://genome.ucsc.edu) to be able to analyze the presence of the polymorphisms of interest in each one of the sequences manually, recording deletions, insertions, and substitutions when compared to the rCRS reference sequence (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/251831106). The methodology used to obtain and process the sequences is summarized in

Figure 1.

The databases were analyzed using R (version 4.0.3)

https://cran.r-project.org/. The absolute and relative frequencies were calculated for the descriptive analysis of the nominal qualitative variables related to the presence or absence of SNPs in a specific locus. The goodness of fit hypothesis used Pearson chi-square (X2) analysis with p < 0.05 and estimated Odds Ratio (OR) and relative risk with their respective 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

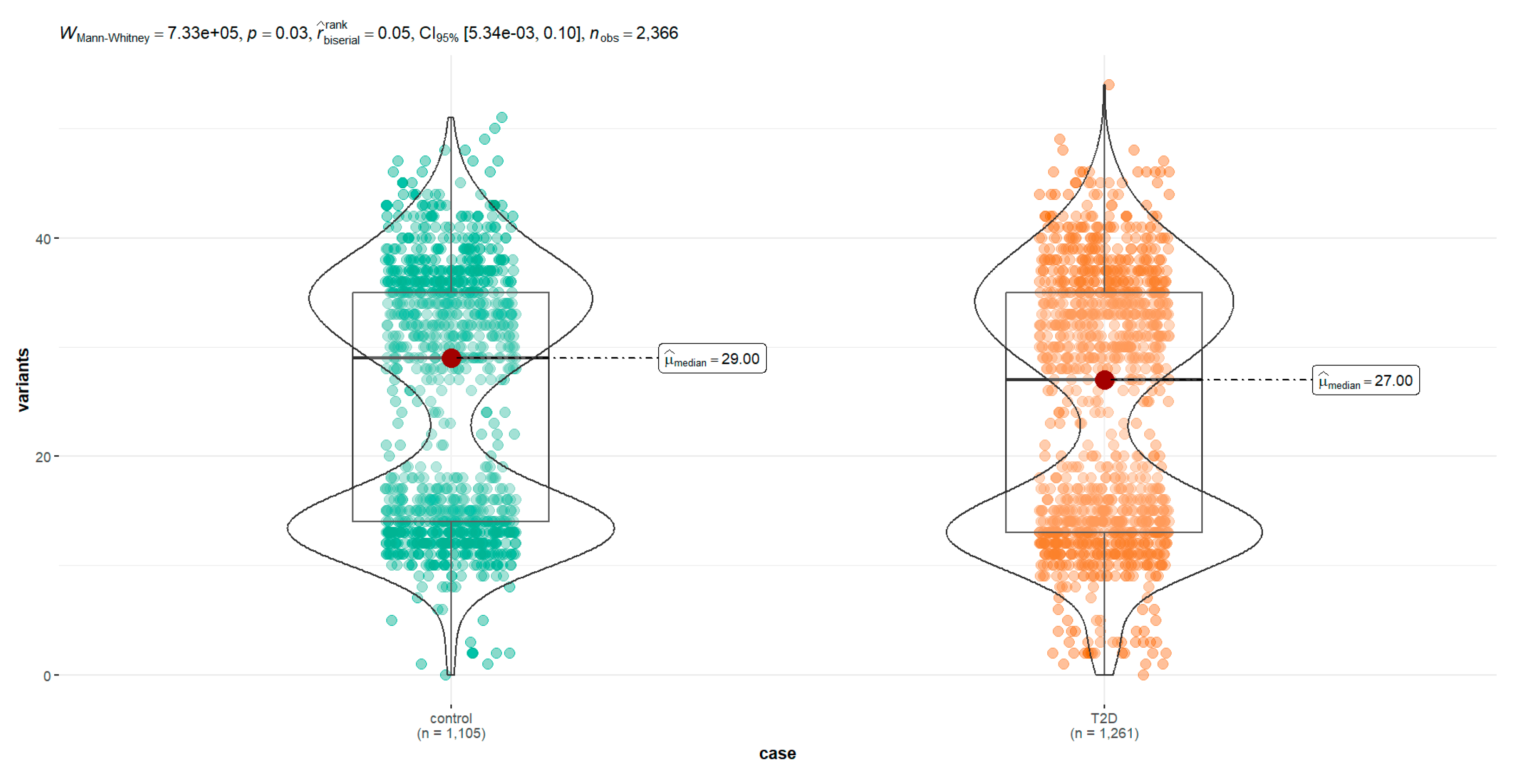

For the descriptive statistical analysis of counts of variants in a single sequence, were performed central tendency statistics as mean, median, and mode; dispersion statistics as standard deviation, standard error, variance, quartiles, interquartile range (IQR), maximum and minimum values; and finally asymmetry metrics as skewness and Kurtosis; To explore normality a frequency histogram, qq plot, and Kolmogorov-Smirnov test with the Lilliefors correction was used to test normal distribution of data and Silverman critical bandwidth test p-value to demonstrate multimodality (Silverman, 1981). To explore variance homoscedasticity, a Levene test was performed. Finally, a comparative analysis of the median of the number of polymorphisms between diabetic y control cases was done using a U Mann Whitney (Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test) with criteria of p-value < 0.05 to confirm statistically significant differences.

Results

The 2,663 mtDNA sequences were identified in the NCBI Nucleotide database, of which 2,366 met the eligibility criteria. 54% (n = 1,261) corresponded to sequences from individuals diagnosed with T2D and 46% (n = 1,105) corresponded to sequences from controlled individuals. The summary of the results of the descriptive statistics of the number of polymorphisms per sequence is shown in Table 1 and the frequency of different haplogroups in Table supplementary S1. After the graphical analysis and the statistical test to explore normality, it is shown that the distribution of the frequency of variants has a non-parametric distribution (Table 1). Normality analysis with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov with Lilliefors correction test, values of D = 0.2 and p < 2 x 10-16 were found, demonstrating the absence of normality and non-parametric distribution of the data. The Silverman test estimated critical bandwidth with 9.09 and p-value < 2.2e-16 demonstrating a true bimodal distribution (

Figure 2).

When analyzed individually by separate groups and plotted using frequency histograms of the variant counts per sequence, this bimodal distribution is maintained in diabetics and controls, so it is not an effect related to differences in the frequencies between the two groups.

With the Levene test to explore the homoscedasticity of the same data, their variances are homogeneous with an F statistic value of 2.21 and a value of p equal to 0.14. Finally, in the Mann-Whitney test, we can demonstrate a significant difference when comparing the median of variants frequency in the diabetic group with controls (

Figure 3).

The descriptive statistics analysis shows that a mean of variants in the diabetic population, most of the variation in control sequences are mainly unique polymorphisms. Only 13 mutations are related in almost 50% of the sequences studied. In contrast, there are up to 22 different polymorphisms in the control sequences. Most variations were found in unique polymorphisms distributed along the mitochondrial genome; however, the most frequent repetition is concentrated in the control region, between positions 576 and 16024 of the mtDNA.

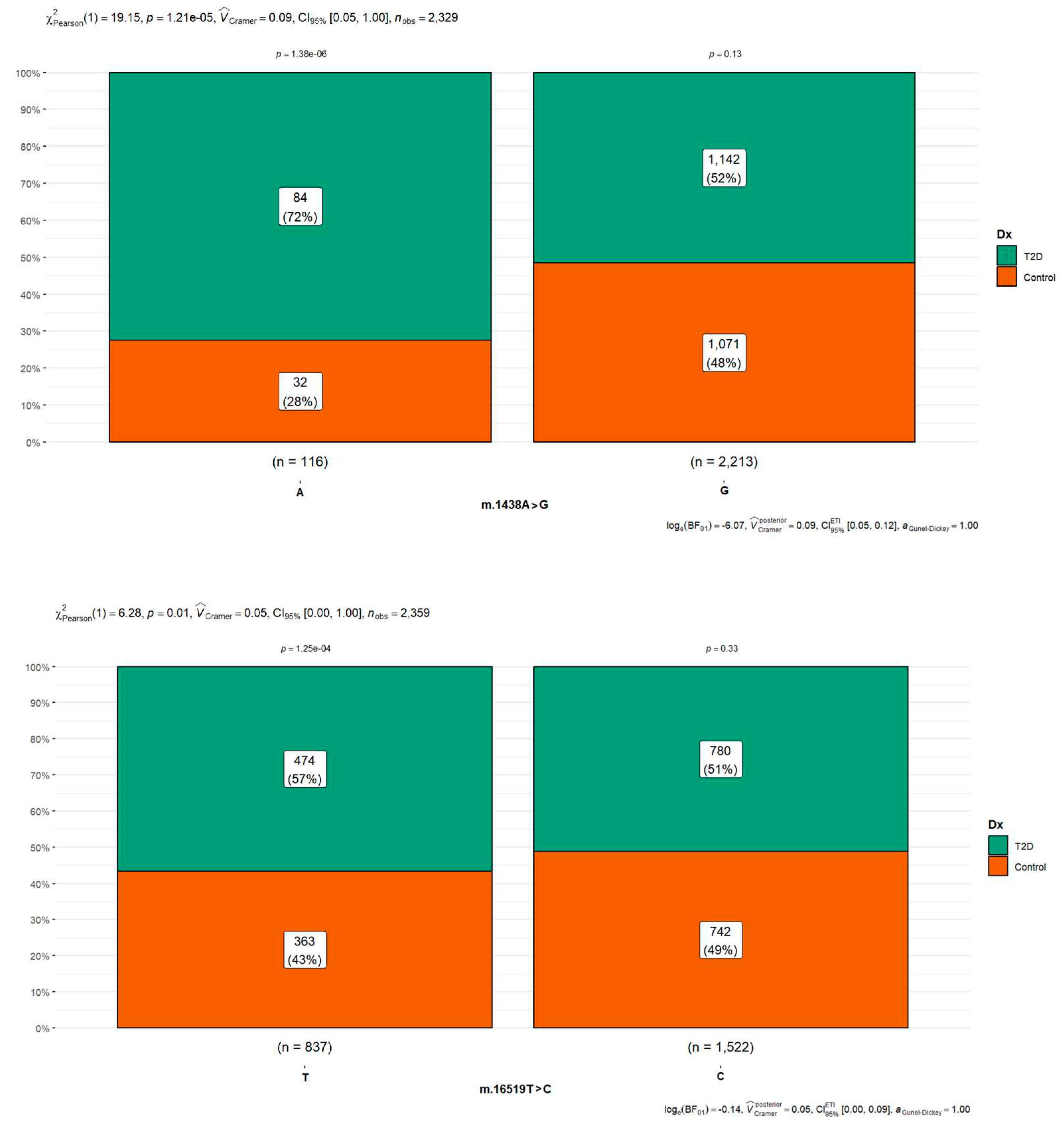

Of the 13,907 SNPs (7,087 in T2D and 6,820 in controls) identified in the sequences after comparison against the rCRS reference sequence, 64% were found to be associated with only five variants (8,901 of which 4,536 are in T2D cases and 4,365 in T2D cases), occupying two-thirds of all the polymorphisms observed in all the samples analyzed. The five most frequently shared polymorphism was m.1438A>G (rs2001030) found in people with diabetes in 97.0% (1071/1104) in diabetic cases and 90.6% (1,142/1,105) in controls (Figure 4), m.750A>G (rs2853518) found in 96.1% (1,211/1,260) of diabetic cases and 96.2% (1071/1105) in controls; m.16519T>C (rs3937033) found with 61.8% (780/1661) in T2D and 67.1% (742/1105) in controls (Figure 4), m.2706A>G (rs28541280) found in 55.5% (700/1,261) of diabetic cases and 58.7% (648/1104) in controls and m.73A>G (rs869183622) found in 56.4% (711/1,261) of diabetic cases and 60.1% 663/1104 in controls) (

Figure 3). Of these more frequent changes found, the m.16519T>C polymorphism was the only significant difference between groups with p-value < 0.05 in the Chi-square test (Figure 4). Concerning variant m.16189T>C (rs386828865), frequently reported in the literature in multiple studies in different populations associated with T2D, was only found in 13.6% (171/1261) of the cases with diabetes and 13.4% (148/1104) of the control cases (

Figure 3), it was not found to be associated with diabetes in our analysis with p-value 0.83, odds ratio 1.03 with 95%CI 0.815-1.31. In the diabetic group, 13.7% of the sequences (187/1,361) do not have SNPs resulting in being identical to the reference sequence; each sequence has, on average, 6 SNPs, with a maximum of 70 variants (

Figure 1), while in the control group, at least 15.9% (176/1,105) of the sequences do not have SNPs, and there is a higher frequency of polymorphisms with a maximum of 146 and an average of 8 SNPs per sequence.

The present research analyzed 80 different mitochondrial polymorphisms previously reported in the literature associated with T2D. In the population of individuals with diabetes, a high prevalence of polymorphisms m.1438A>G and m.16519T>C was found in more than half of the sequences analyzed, with significant differences concerning control cases. On the other hand, the variants m.1811A>G, m.3027T>C, m.14766C>T, and m.16126T>C were slightly more common in the controls, also with statistically significant differences (Table 2).

Discussion

Although there is a well-established relationship between mitochondrial physiology and T2D, mitochondrial dysfunction can hurt glucose metabolism and contribute to the development of the disease; changes in the sequence of the mitochondrial genome could have some role in the related pathophysiology, have been found recurrently and associated with specific populations. Some of the ways that mitochondrial dysfunction can be linked to T2D are related to decreased energy production, oxidative stress, altered metabolism of fatty acids, inflammation, and cell signaling. Mitochondria are responsible for the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the primary source of energy for cells, and dysfunction can reduce ATP production, which can affect cells’ ability to metabolize glucose and regulate blood sugar levels properly. In the same way, this mitochondrial dysfunction can lead to increased production of reactive oxygen species, resulting in oxidative stress. Oxidative stress can damage cells and tissues, including the insulin-producing beta cells of the pancreas, leading to decreased insulin secretion and insulin resistance, critical features of T2D. Likewise, mitochondria play an essential role in the metabolism of fatty acids, an important energy source for cells, and mitochondrial dysfunction can disrupt fatty acid metabolism, contributing to lipid storage and insulin resistance. Mitochondrial dysfunction can trigger inflammatory responses in cells and contribute to the dysfunction of cell signaling pathways so that these changes may affect the function of pancreatic beta cells, as well as the response of peripheral tissues to insulin, which may contribute to the development of intolerance to carbohydrates (Galicia-Garcia et al., 2020).

Although it is well known that the area of the mitochondrial chromosome with the most significant variability is the control region where more than 90% of the changes are grouped when comparing different sequences (Andrews et al., 1999; Kong et al., 2006; Mishmar et al., 2003; Ruiz-Pesini et al., 2004; Torroni et al., 2006; Umetsu & Yuasa, 2005), it is noteworthy that the identified polymorphisms are concentrated in two loci related to the synthesis of mitochondrial ribosomal subunits: four variants, m.1189T>C, m.1193T>C, m.1420T>C and m.1438A>G in gene MT-RNR1 locus coding for the 12S ribosomal RNA, and three variants m.1811A>G, m.2667T>C and m.3027T>C in gene MT-RNR2 locus coding for the 16S ribosomal RNA. This important mtDNA region is related to MDP, encoded in the mitochondrial genome and translated into the mitochondria or cell cytoplasm, and released to bind to extracellular membrane receptors, active participation in cellular metabolism as a source of regulation factors of metabolic stress.

Previous analysis of our research team report three variants in the MT-RNR1 not related to the MOTS-c coding sequence: m.1189T>C (rs28358571), m.1420T>C (rs111033356), and m.1438A>G (rs2001030); and secondly, three polymorphisms associated to MT-RNR2 m.2667T>C (rs878870626) related to humans, m.1811A>G (rs28358576) in SHPL3 and m.3027T>C (rs199838004) in SHPL6 associated with statistical differences between the T2D and control group. All these findings were previously related to cardiovascular complications in literature and, as far as we know, related for the first time in diabetic patients (Gaona et al., 2022).

The available evidence is compelling about the highly nuanced and bi-directional relationship between mitochondria and diabetes. On the one hand, aspects of T2D, such as insulin resistance, can lead to mitochondrial dysfunction, such as through energy overload leading to ROS excess production. Otherwise, mitochondrial dysfunction may lead to subsequently developing T2D, as evidenced by the presence of mitochondrial SNPs associated with this metabolic disease.

Some of these pathophysiological phenomena, clearly associated with mitochondrial dysfunction, may be associated with variants in their genome and the proportion of mitochondria with these changes in essential tissues linked to the disease, such as striated muscle fibers, adipocytes, hepatocytes, and pancreatic beta cells (Avital et al., 2012; Højlund et al., 2008; Nissanka & Moraes, 2020; Rambani et al., 2022; Vringer & Tait, 2023). In addition, the role of mitochondrial genetics in the risk of the diabetic phenotype has been established, relating it to several mtDNA changes that have been associated with the development of T2D, like heteroplasmic variants associated with increased risk of carbohydrate intolerance develop as m.3243A>G, m.14577T>C, and m. 5178A>C (Kadowaki et al., 1994; Tawata et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2012) and homoplasmic variants that include m.1310C>T, m.1438GA>G, m.12026A>G, m.16189T>C, and 14693A>G (Poulton et al., 2002; Tang et al., 2006; Tawata et al., 1998).

In the descriptive statistical analysis, the variants are more frequent with statistical significance in controls than diabetic population. Also of note is the bimodal distribution of the number of SNPs per sequence, both in people with diabetes and in controls, the first and most important where the mode is centralized, with 13 variants per sequence, and the second peak between 30 and 35 variants by sequence. A bimodal distribution with two maximum points makes the mean and median useless since their values will be somewhere between the two maximum points and will likely distort the distribution description.

This genomic bimodal architecture is found in other places, at the same level of complexity as in the canalization phenomena (Davey et al., 2003; Hallgrimsson et al., 2019) in the nuclear genome, but also found in other levels of human DNA complexity, like in the GC proportion in the third positions of the codons, which are the ones with the greatest freedom to change without altering the encoded amino acid (Lamolle et al., 2018) and genetic expression of neoplastic malignant cells (Justino et al., 2021; Moody et al., 2019, 2022). That is, the compositional characteristics of the genome constitute a genotype; for what we propose in the future, this bimodal distribution of variants frequency per sequence should be explored by analyzing a more extensive sequence set with more diverse haplogroups (Table supplementary S1).

In our actual research, 80 polymorphisms of patients with T2D were analyzed. A notorious prevalence was found with significant statistical differences between diabetic and controls in five polymorphisms: m.1438A>G (89.27%), m.14766C>T (75%), m.16519T>C (51.34%), m.10398A>G (44.82%) and m.16189T>C (25.28%).

These changes were found in different mitochondrial regions (Table 2), the m.1438A>G polymorphism (rs2001030), the most frequent change found in our analysis, are in MT-RNR1 gene coding for the 12S ribosomal RNA.; m.14676C>T polymorphism, also known as rs193302980, are placed in the MT-TE gene coding for position 71 in the acceptor stem of tRNA-Glu; m.16519T>C (rs3937033) is a variant in mitochondrial DNA in the noncoding position in a previous comprehensive study, it was found that there is a statistically significant association between the m.16519T>C variant and the prevalence of type 2 diabetes, it was observed that individuals possessing the m.16519T>C variant demonstrated a 69% increase in the odds of developing T2D (OR = 1.69, CI = 1.23–2.33, p = 0.006) (Santander-Lucio et al., 2023); m.10398A>G also known as rs2853826 in the MT-ND3 gene coding for subunit ND3 of complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) at first nucleotide of codon 114 (ACC) for threonine; and finally, m.16189T>C polymorphism (rs28693675) in the hypervariable segment 1 (locus MT-HV1, 16024 - 16383) at mitochondrial DNA replication control region. These variants have been previously investigated for different diseases and conditions, including T2D. Some studies have examined the association between these SNPs and the risk of developing the disease; however, the results have been inconsistent, and a conclusive association has not yet been established. Due to the lack of consensus on the association between our variants and type 2 diabetes, more research in different populations and more extensive studies are needed to understand their relationship better.

Mitochondrial dysfunction and T2D are complex and multifactorial phenomena that involve a complex interaction between genetic and environmental factors. Although mitochondrial dysfunction may be a common feature in diabetic cases, it is essential to note that many changes in the mitochondrial chromosome sequence obtained could result from oxidative damage in sensitive mtDNA regions rather than the origin of metabolic dysfunction.

Previous reports remark on a high prevalence in individuals belonging to haplogroup B, a highly worldwide distributed group that is recognized for its diabetogenic nature, so its study is particularly relevant in different populations also associated with other phenotypes and syndromic diseases related to carbohydrate intolerance (Mkaouar-Rebai et al., 2008; Nahili et al., 2010; Tabebi et al., 2017). Our analysis found a higher prevalence in haplogroups R0, JT, and U. Haplogroup R0, formerly called pre-HV, is a typical Western Eurasian human mitochondrial haplogroup that evolved in Ice Age oases in South Arabia around 22,000 years ago and descended from haplogroup R, giving rise to haplogroups HV and R0a’b; haplogroup JT also euroasiatic distribution probably originated in Southwest Asia 50,300 years ago; and haplogroup U also a typical of Western Eurasia arose from haplogroup R, likely during the early Upper Paleolithic. Recent research suggests that haplogroups R0 and J may decrease the risk of diabetes mellitus (Alwehaidah et al., 2021; Kwak & Park, 2016) but are related to complicated diabetic disease in other human groups (Diaz-Morales et al., 2018)

These discrepancies could be attributed to differences in the populations studied, confounding factors, and methodological limitations. Mitochondrial polymorphisms, including our variants found, may have an additive effect or interact with other genetic and environmental factors to contribute to disease risk. Given the lack of consensus on the association between SNPs and T2D, more research is needed in different populations. In the same way, other processes of analyzing nonlinear complex patterns in DNA sequences should be developed. For example, data mining techniques such as association rules can reveal hidden relationships between these variants to find the combination of mitochondrial polymorphism that coincides. Association rules can be used to reveal biologically relevant associations between biological information about different combinations of the presence or absence of nucleotides in known positions (Czibula et al., 2012; Leung et al., 2010; Mallik et al., 2015; Oellrich et al., 2014; Wong et al., 2015). homoplasmic variants that includes m.1310C>T, m.1438GA>G, m.12026A>G, m.16189T>C, and 14693A>G (Poulton et al., 2002; Tang et al., 2006; Tawata et al., 1998).

In the descriptive statistical analysis the variants are more frequent with statistical significance in controls than diabetic population. Also of note is the bimodal distribution of the number of SNPs per sequence, both in diabetics and in controls, the first and most important where the mode is centralized, with 13 variants per sequence, and the second peak between 30 and 35 variants by sequence. A bimodal distribution with two maximum points makes the mean and median useless, since their values will be somewhere between the two maximum points and will likely distort the description of the distribution.

This genomic bimodal architecture is found in other places, at the same level of complexity like in the canalisation phenomena (Davey Smith & Ebrahim, 2003; Hallgrimsson et al., 2019) in nuclear genome; but also are found in other levels of human DNA complexity, like in the GC proportion in the third positions of the codons, which are the ones with the greatest freedom to change without altering the encoded amino acid (Lamolle et al., 2018) and genetic expression of neoplasic malignant cells (Justino et al., 2021; Moody et al., 2019, 2022). That is, probably the compositional characteristics of the genome constitute, by themselves, a genotype, for what we propose in the future this bimodal distribution of variants frequency per sequence should be explored analyzing a larger sequence set and with more diverse haplogroups.

In our actual research , 80 polymorphisms of patients with T2D were analyzed. A notorious prevalence was found with significant statistical differences between diabetic and controls in five polymorphisms: m.1438A>G (89.27%), m.14766C>T (75%), m.16519T>C (51.34%), m.10398A>G (44.82%) and m.16189T>C (25.28%).

These changes were found in different mitochondrial regions (Table 2), the m.1438A>G polymorphism (rs2001030), the most frequent change found in our analysis, are in MT-RNR1 gene coding for the 12S ribosomal RNA.; m.14676C>T polymorphism, also known as rs193302980, are placed in the MT-TE gene coding for position 71 in the acceptor stem of tRNA-Glu; m.16519T>C (rs3937033) is a variant in mitochondrial DNA in the noncoding position in a previous comprehensive study, it was found that there is a statistically significant association between the m.16519T>C variant and the prevalence of type 2 diabetes, it was observed that individuals possessing the m.16519T>C variant demonstrated a 69% increase in the odds of developing T2D (OR = 1.69, CI = 1.23–2.33, p = 0.006) (Santander-Lucio et al., 2023); m.10398A>G also known as rs2853826 in the MT-ND3 gene coding for subunit ND3 of complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) at first nucleotide of codon 114 (ACC) for threonine; and finally, m.16189T>C polymorphism (rs28693675) in the hypervariable segment 1 (locus MT-HV1, 16024 - 16383) at mitochondrial DNA replication control region. These variants have been previously investigated in relation to different diseases and conditions, including T2D. Some studies have examined the association between these SNPs and the risk of developing the disease, however, the results have been inconsistent and a conclusive association has not yet been established. Due to the lack of consensus on the association between our variants and type 2 diabetes, more research in different populations and larger studies are needed to better understand their relationship.

Mitochondrial dysfunction and T2D are complex and multifactorial phenomena that involve a complex interaction between genetic and environmental factors. Although mitochondrial dysfunction may be a common feature diabetic cases, it is important to note that many of changes in the mitochondrial chromosomes sequence obtained could be the result of oxidative damage in sensitive mtDNA regions, rather than the origin of metabolic dysfunction.

Previous reports remarks a high prevalence in individuals belonging to haplogroup B, a highly worldwide distributed group that is recognized for its diabetogenic nature, so its study is particularly relevant in different populations also associated with other phenotypes and syndromic diseases related with carbohydrate intolerance (Mkaouar-Rebai et al., 2008; Nahili et al., 2010; Tabebi et al., 2017). In our analysis found a higher prevalence in haplogroups R0, JT and U. Haplogroup R0, formerly called pre-HV, is a typical Western Eurasian human mitochondrial haplogroup evolved in Ice Age oases in South Arabia around 22,000 years ago and descended from haplogroup R, giving rise to haplogroups HV and R0a’b; haplogroup JT also euroasiatic distribution probably originated in Southwest Asia 50,300 years ago; and haplogroup U also a typical of Western Eurasia arose from haplogroup R, likely during the early Upper Paleolithic. Recent research suggests that haplogroups R0 and J may decrease the risk of diabetes mellitus (Alwehaidah et al., 2021; Kwak & Park, 2016), but are related with complicated diabetic disease in other human groups (Diaz-Morales et al., 2018)

These discrepancies could be attributed to differences in the populations studied, confounding factors, and methodological limitations. Mitochondrial polymorphisms, including our variants found, may have an additive effect or interact with other genetic and environmental factors to contribute to disease risk. Given the lack of consensus on the association between the SNPs and T2D, more research is needed in different populations. In the same way, other processes of analyzing nonlinear complex patterns in DNA sequences should be developed. For example, data mining techniques such as association rules can reveal hidden relationships between these variants to find the combination of mitochondrial polymorphism that occur at the same time. Association rules can be used to reveal biologically relevant associations between biological information about different combinations of presence or absence of nucleotides in known positions (Czibula et al., 2012; Leung et al., 2010; Mallik et al., 2015; Oellrich et al., 2014; Wong et al., 2015).

Conclusions

Although the relationship between mitochondrial polymorphisms, such as SNPs, and T2D has been studied in the past, it is essential to highlight that the contribution is a topic under constant study, and the possible associations and underlying mechanisms are still being investigated. Some studies have suggested possible associations between specific mitochondrial variants and the risk of these metabolic diseases developing. For example, SNPs in mitochondrial genes related to energy production and glucose homeostasis can affect mitochondrial function, insulin sensitivity, and glucose metabolism, influencing susceptibility to T2D. Some examples of mitochondrial variants that have been previously reported and investigated concerning diabetes, also found in our analysis, usually are related to mitochondrial DNA replication control region and mitochondrial metabolic energy essential genes. It has been suggested that it may be associated with increased susceptibility and risk of developing diabetes. However, it is worth noting that studies on the relationship between mitochondrial variants and T2D have been inconsistent in some cases; some studies have found significant associations, while others have yet to find a clear correlation, or the results have been conflicting. The complexity of diabetes as a multifactorial disease means that multiple genetic and environmental factors may contribute to its development. Furthermore, the interaction between mitochondrial and nuclear genes may also be essential in disease susceptibility.

Overall, research on the relationship between mitochondrial polymorphisms and T2D is ongoing, and further studies are needed to fully understand the underlying mechanisms and clinical relevance of these associations. It is important to note that these are just examples of some of the mitochondrial SNPs that have been investigated about T2D, the presence of these sequence changes does not necessarily imply risk or a direct association with disease in all populations or individuals.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Frequency distribution of the different haplogroups in diabetic and control cases; Table S2: Descriptive statistics of mtDNA polymorphism frequencies in 2,633 sequences; Table S3: Frequency of most frequent mitochondrial single nucleotide polymorphisms in type 2 diabetes and controls; Table S4: mtDNA database with

NCBI Nucleotide sequence ID, predicted haplogroup, total variants per sequence and list of variants identified per sequence for T2D and controls (Data obtained from

MITOMASTER analysis

https://www.mitomap.org/mitomaster/index.cgi); Table S4: List of participants in the project during the Pacific Scientific and Technological Research Summer Program 2019-2022.

Funding

We appreciate the support for publication through the PRO-SNI 2023 program to researchers from the University of Guadalajara. This project did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

The identification for access to the sequences used for this work is fully referred to in Table supplementary S3 and is available from the NCBI Nucleotide database (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore).

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the kind help of Anders Albretchsen at the University of Copenhagen (Denmark), Rasmus Nielsen at the University of California Berkeley (U.S.A), Mikkel Schierup Aarhus at University (Denmark), and Shengting Li at MGI-Tech Co (Shenzhen, China) for sequences identification. Also, we acknowledge the support of Verónica Lizette Robles Dueñas in the facilities for work meetings and support infrastructure at the Data Analysis and Supercomputing Center of the University de Guadalajara. Notably, we thank all collaborators who participated during the summer research through the Delfin program

https://programadelfin.org.mx/ during 2019-2022 and actively participated in planning, data mining, and discussion of results to materialize this work. We share the participants’ list, and their institutional affiliations in the Table supplementary S2.

Competing Interest Statement

The authors of this work declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmad, E., Lim, S., Lamptey, R., Webb, D. R., & Davies, M. J. (2022). Type 2 diabetes. Lancet (London, England), 400(10365), 1803-1820. [CrossRef]

- Alwehaidah, M. S., Al-Kafaji, G., Bakhiet, M., & Alfadhli, S. (2021). Next-generation sequencing of the whole mitochondrial genome identifies novel and common variants in patients with psoriasis, type 2 diabetes mellitus and psoriasis with comorbid type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biomedical Reports, 14(5), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R. M., Kubacka, I., Chinnery, P. F., Lightowlers, R. N., Turnbull, D. M., & Howell, N. (1999). Reanalysis and revision of the Cambridge reference sequence for human mitochondrial DNA. Nature Genetics, 23(2), Article 2. [CrossRef]

- Asmann, Y. W., Stump, C. S., Short, K. R., Coenen-Schimke, J. M., Guo, Z., Bigelow, M. L., & Nair, K. S. (2006). Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Functions, Mitochondrial DNA Copy Numbers, and Gene Transcript Profiles in Type 2 Diabetic and Nondiabetic Subjects at Equal Levels of Low or High Insulin and Euglycemia. Diabetes, 55(12), 3309-3319. [CrossRef]

- Avital, G., Buchshtav, M., Zhidkov, I., Tuval (Feder), J., Dadon, S., Rubin, E., Glass, D., Spector, T. D., & Mishmar, D. (2012). Mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy in diabetes and normal adults: Role of acquired and inherited mutational patterns in twins. Human Molecular Genetics, 21(19), 4214-4224. [CrossRef]

- Befroy, D. E., Petersen, K. F., Dufour, S., Mason, G. F., de Graaf, R. A., Rothman, D. L., & Shulman, G. I. (2007). Impaired mitochondrial substrate oxidation in muscle of insulin-resistant offspring of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes, 56(5), 1376-1381. [CrossRef]

- Boushel, R., Gnaiger, E., Schjerling, P., Skovbro, M., Kraunsøe, R., & Dela, F. (2007). Patients with type 2 diabetes have normal mitochondrial function in skeletal muscle. Diabetologia, 50(4), 790-796. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.-Z., & Gerszten, R. E. (2020). Metabolomics and Proteomics in Type 2 Diabetes. Circulation Research, 126(11), 1613-1627. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A. J., Gupta, S. R., Moustafa, A. F., & Chao, A. M. (2021). Sex/Gender Differences in Obesity Prevalence, Comorbidities, and Treatment. Current Obesity Reports, 10(4), 458-466. [CrossRef]

- Cousin, E., Schmidt, M. I., Ong, K. L., Lozano, R., Afshin, A., Abushouk, A. I., Agarwal, G., Agudelo-Botero, M., Al-Aly, Z., Alcalde-Rabanal, J. E., Alvis-Guzman, N., Alvis-Zakzuk, N. J., Antony, B., Asaad, M., Bärnighausen, T. W., Basu, S., Bensenor, I. M., Butt, Z. A., Campos-Nonato, I. R., … Duncan, B. B. (2022). Burden of diabetes and hyperglycaemia in adults in the Americas, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 10(9), 655-667. [CrossRef]

- Czibula, G., Bocicor, M.-I., & Czibula, I. G. (2012). Promoter Sequences Prediction Using Relational Association Rule Mining. Evolutionary Bioinformatics, 8, EBO.S9376. [CrossRef]

- Davey Smith, G., & Ebrahim, S. (2003). ‘Mendelian randomization’: Can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease?*. International Journal of Epidemiology, 32(1), 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Dela, F., & Helge, J. W. (2013). Insulin resistance and mitochondrial function in skeletal muscle. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology, 45(1), 11-15. [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Morales, N., Lopez-Domenech, S., Iannantuoni, F., Lopez-Gallardo, E., Sola, E., Morillas, C., Rocha, M., Ruiz-Pesini, E., & Victor, V. M. (2018). Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroup JT is Related to Impaired Glycaemic Control and Renal Function in Type 2 Diabetic Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 7(8), Article 8. [CrossRef]

- Fex, M., Nicholas, L. M., Vishnu, N., Medina, A., Sharoyko, V. V., Nicholls, D. G., Spégel, P., & Mulder, H. (2018). The pathogenetic role of β-cell mitochondria in type 2 diabetes. The Journal of Endocrinology, 236(3), R145-R159. [CrossRef]

- Floris, M., Sanna, D., Castiglia, P., Putzu, C., Sanna, V., Pazzola, A., De Miglio, M. R., Sanges, F., Pira, G., Azara, A., Lampis, E., Serra, A., Carru, C., Steri, M., Costanza, F., Bisail, M., & Muroni, M. R. (2020). MTHFR, XRCC1 and OGG1 genetic polymorphisms in breast cancer: A case-control study in a population from North Sardinia. BMC Cancer, 20, 234. [CrossRef]

- Galicia-Garcia, U., Benito-Vicente, A., Jebari, S., Larrea-Sebal, A., Siddiqi, H., Uribe, K. B., Ostolaza, H., & Martín, C. (2020). Pathophysiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(17), Article 17. [CrossRef]

- Gaona, E. G., Gregorio, A. G., Jiménez, C. G., López-Olaiz, M. A., Mendoza-Ramírez, P., Fernandez-Guzman, D., Zuñiga, L. Y., Sánchez-Parada, M. G., Santiago, A. E. G., Pintos, L. M. R., Arellano, R. C., Hernández-Ortega, L. D., Sesma, A. R. M., Orozco-Luna, F. de J., & Rosas, R. C. B. (2022). Mitochondrial-derived Peptide Single-nucleotide Polymorphisms Associated with Cardiovascular Complications in Type 2 Diabetes (2022100025). [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.-J., Oshida, Y., Fuku, N., Takeyasu, T., Fujita, Y., Kurata, M., Sato, Y., Ito, M., & Tanaka, M. (2005). Mitochondrial genome polymorphisms associated with type-2 diabetes or obesity. Mitochondrion, 5(1), 15-33. [CrossRef]

- Hallgrimsson, B., Green, R. M., Katz, D. C., Fish, J. L., Bernier, F. P., Roseman, C. C., Young, N. M., Cheverud, J. M., & Marcucio, R. S. (2019). The developmental-genetics of canalization. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology, 88, 67-79. [CrossRef]

- He, J., Watkins, S., & Kelley, D. E. (2001). Skeletal Muscle Lipid Content and Oxidative Enzyme Activity in Relation to Muscle Fiber Type in Type 2 Diabetes and Obesity. Diabetes, 50(4), 817-823. [CrossRef]

- Hesselink, M. K. C., Schrauwen-Hinderling, V., & Schrauwen, P. (2016). Skeletal muscle mitochondria as a target to prevent or treat type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 12(11), Article 11. [CrossRef]

- Hittel, D. S., Hathout, Y., Hoffman, E. P., & Houmard, J. A. (2005). Proteome Analysis of Skeletal Muscle From Obese and Morbidly Obese Women. Diabetes, 54(5), 1283-1288. [CrossRef]

- Højlund, K., & Beck-Nielsen, H. (2006a). Impaired glycogen synthase activity and mitochondrial dysfunction in skeletal muscle: Markers or mediators of insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes? Current Diabetes Reviews, 2(4), 375-395. [CrossRef]

- Højlund, K., & Beck-Nielsen, H. (2006b). Impaired glycogen synthase activity and mitochondrial dysfunction in skeletal muscle: Markers or mediators of insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes? Current Diabetes Reviews, 2(4), 375-395. [CrossRef]

- Højlund, K., Mogensen, M., Sahlin, K., & Beck-Nielsen, H. (2008). Mitochondrial dysfunction in type 2 diabetes and obesity. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America, 37(3), 713-731, x. [CrossRef]

- Højlund, K., Wrzesinski, K., Larsen, P. M., Fey, S. J., Roepstorff, P., Handberg, A., Dela, F., Vinten, J., McCormack, J. G., Reynet, C., & Beck-Nielsen, H. (2003). Proteome Analysis Reveals Phosphorylation of ATP Synthase β-Subunit in Human Skeletal Muscle and Proteins with Potential Roles in Type 2 Diabetes *. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 278(12), 10436-10442. [CrossRef]

- Justino, J. R., Reis, C. F. dos, Fonseca, A. L., Souza, S. J. de, & Stransky, B. (2021). An integrated approach to identify bimodal genes associated with prognosis in câncer. Genetics and Molecular Biology, 44, e20210109. [CrossRef]

- Kadowaki, T., Kadowaki, H., Mori, Y., Tobe, K., Sakuta, R., Suzuki, Y., Tanabe, Y., Sakura, H., Awata, T., Goto, Y., Hayakawa, T., Matsuoka, K., Kawamori, R., Kamada, T., Horai, S., Nonaka, I., Hagura, R., Akanuma, Y., & Yazaki, Y. (1994). A Subtype of Diabetes Mellitus Associated with a Mutation of Mitochondrial DNA. New England Journal of Medicine, 330(14), 962-968. [CrossRef]

- Kautzky-Willer, A., Harreiter, J., & Pacini, G. (2016). Sex and Gender Differences in Risk, Pathophysiology and Complications of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Endocrine Reviews, 37(3), 278-316. [CrossRef]

- Kelley, D. E., He, J., Menshikova, E. V., & Ritov, V. B. (2002). Dysfunction of Mitochondria in Human Skeletal Muscle in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes, 51(10), 2944-2950. [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.-P., Bandelt, H.-J., Sun, C., Yao, Y.-G., Salas, A., Achilli, A., Wang, C.-Y., Zhong, L., Zhu, C.-L., Wu, S.-F., Torroni, A., & Zhang, Y.-P. (2006). Updating the East Asian mtDNA phylogeny: A prerequisite for the identification of pathogenic mutations. Human Molecular Genetics, 15(13), 2076-2086. [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg, F., & Eckardt, K.-U. (2022). Mitochondrial DNA and Kidney Function. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN, 17(7), 942-944. [CrossRef]

- Kruszynska, Y. T., Mulford, M. I., Baloga, J., Yu, J. G., & Olefsky, J. M. (1998). Regulation of skeletal muscle hexokinase II by insulin in nondiabetic and NIDDM subjects. Diabetes, 47(7), 1107-1113. [CrossRef]

- Kwak, S. H., & Park, K. S. (2016). Role of mitochondrial DNA variation in the pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus. Frontiers in Bioscience-Landmark, 21(6), Article 6. [CrossRef]

- Kwak, S. H., Park, K. S., Lee, K.-U., & Lee, H. K. (2010). Mitochondrial metabolism and diabetes. Journal of Diabetes Investigation, 1(5), 161-169. [CrossRef]

- Lamolle, G., Musto, H., Lamolle, G., & Musto, H. (2018). Genoma Humano. Aspectos estructurales. Anales de la Facultad de Medicina, 5(2), 12-28. [CrossRef]

- Langenberg, C., & Lotta, L. A. (2018). Genomic insights into the causes of type 2 diabetes. Lancet (London, England), 391(10138), 2463-2474. [CrossRef]

- Leung, K.-S., Wong, K.-C., Chan, T.-M., Wong, M.-H., Lee, K.-H., Lau, C.-K., & Tsui, S. K. W. (2010). Discovering protein–DNA binding sequence patterns using association rule mining. Nucleic Acids Research, 38(19), 6324-6337. [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Xiang, Y., Zhang, Y., Tang, D., Chen, Y., Xue, W., Wang, X., Chen, J., & Dai, Y. (2022). A preliminary analysis of mitochondrial DNA atlas in the type 2 diabetes patients. International Journal of Diabetes in Developing Countries, 42(4), 713-720. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Jiang, R., Cong, X., & Zhao, Y. (2019). UCP2 gene polymorphisms in obesity and diabetes, and the role of UCP2 in cancer. FEBS Letters, 593(18), 2525-2534. [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.-Q., Pang, Y., Yu, C.-A., Wen, J.-Y., Zhang, Y.-G., & Li, X.-H. (2008). Novel mutations of mitochondrial DNA associated with type 2 diabetes in Chinese Han population. The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine, 215(4), 377-384. [CrossRef]

- Lightowlers, R. N., Chinnery, P. F., Turnbull, D. M., & Howell, N. (1997). Mammalian mitochondrial genetics: Heredity, heteroplasmy and disease. Trends in Genetics, 13(11), 450-455. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X., Xu, Y., Pan, X., Xu, J., Ding, Y., Sun, X., Song, X., Ren, Y., & Shan, P.-F. (2020). Global, regional, and national burden and trend of diabetes in 195 countries and territories: An analysis from 1990 to 2025. Scientific Reports, 10(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Ren, Z.-H., Qiang, H., Wu, J., Shen, M., Zhang, L., & Lyu, J. (2020). Trends in the incidence of diabetes mellitus: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 and implications for diabetes mellitus prevention. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1415. [CrossRef]

- Lott, M. T., Leipzig, J. N., Derbeneva, O., Xie, H. M., Chalkia, D., Sarmady, M., Procaccio, V., & Wallace, D. C. (2013). MtDNA Variation and Analysis Using Mitomap and Mitomaster. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics, 44(1), 1.23.1-1.23.26. [CrossRef]

- Mallik, S., Mukhopadhyay, A., & Maulik*, U. (2015). RANWAR: Rank-Based Weighted Association Rule Mining From Gene Expression and Methylation Data. IEEE Transactions on NanoBioscience, 14(1), 59-66. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Jiménez, R., Lurette, O., & Hebert-Chatelain, E. (2020). Damage in Mitochondrial DNA Associated with Parkinson’s Disease. DNA and Cell Biology, 39(8), 1421-1430. [CrossRef]

- Mishmar, D., Ruiz-Pesini, E., Golik, P., Macaulay, V., Clark, A. G., Hosseini, S., Brandon, M., Easley, K., Chen, E., Brown, M. D., Sukernik, R. I., Olckers, A., & Wallace, D. C. (2003). Natural selection shaped regional mtDNA variation in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(1), 171-176. [CrossRef]

- Mkaouar-Rebai, E., Tlili, A., Masmoudi, S., Charfeddine, I., & Fakhfakh, F. (2008). New polymorphic mtDNA restriction site in the 12S rRNA gene detected in Tunisian patients with non-syndromic hearing loss. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 369(3), 849-852. [CrossRef]

- Mogensen, M., Sahlin, K., Fernström, M., Glintborg, D., Vind, B. F., Beck-Nielsen, H., & Højlund, K. (2007). Mitochondrial Respiration Is Decreased in Skeletal Muscle of Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes, 56(6), 1592-1599. [CrossRef]

- Moody, L., Mantha, S., Chen, H., & Pan, Y.-X. (2019). Computational methods to identify bimodal gene expression and facilitate personalized treatment in cancer patients. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 100, 100001. [CrossRef]

- Moody, L., Xu, G. B., Pan, Y.-X., & Chen, H. (2022). Genome-wide cross-cancer analysis illustrates the critical role of bimodal miRNA in patient survival and drug responses to PI3K inhibitors. PLoS Computational Biology, 18(5), e1010109. [CrossRef]

- Morino, K., Petersen, K. F., Dufour, S., Befroy, D., Frattini, J., Shatzkes, N., Neschen, S., White, M. F., Bilz, S., Sono, S., Pypaert, M., & Shulman, G. I. (2005). Reduced mitochondrial density and increased IRS-1 serine phosphorylation in muscle of insulin-resistant offspring of type 2 diabetic parents. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 115(12), 3587-3593. [CrossRef]

- Morino, K., Petersen, K. F., & Shulman, G. I. (2006). Molecular Mechanisms of Insulin Resistance in Humans and Their Potential Links With Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Diabetes, 55(Supplement_2), S9-S15. [CrossRef]

- Mulder, H. (2017). Transcribing β-cell mitochondria in health and disease. Molecular Metabolism, 6(9), 1040-1051. [CrossRef]

- Nahili, H., Charif, M., Boulouiz, R., bounaceur, S., Benrahma, H., Abidi, O., Chafik, A., Rouba, H., Kandil, M., & Barakat, A. (2010). Prevalence of the mitochondrial A 1555G mutation in Moroccan patients with non-syndromic hearing loss. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 74(9), 1071-1074. [CrossRef]

- Naue, J., Hörer, S., Sänger, T., Strobl, C., Hatzer-Grubwieser, P., Parson, W., & Lutz-Bonengel, S. (2015). Evidence for frequent and tissue-specific sequence heteroplasmy in human mitochondrial DNA. Mitochondrion, 20, 82-94. [CrossRef]

- Nissanka, N., & Moraes, C. T. (2020). Mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy in disease and targeted nuclease-based therapeutic approaches. EMBO reports, 21(3), e49612. [CrossRef]

- Oellrich, A., Jacobsen, J., Papatheodorou, I., The Sanger Mouse Genetics Project, & Smedley, D. (2014). Using association rule mining to determine promising secondary phenotyping hypotheses. Bioinformatics, 30(12), i52-i59. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, K. F., Befroy, D., Dufour, S., Dziura, J., Ariyan, C., Rothman, D. L., DiPietro, L., Cline, G. W., & Shulman, G. I. (2003). Mitochondrial Dysfunction in the Elderly: Possible Role in Insulin Resistance. Science (New York, N.Y.), 300(5622), 1140-1142. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, K. F., Dufour, S., Befroy, D., Garcia, R., & Shulman, G. I. (2004). Impaired mitochondrial activity in the insulin-resistant offspring of patients with type 2 diabetes. The New England Journal of Medicine, 350(7), 664-671. [CrossRef]

- Phielix, E., Schrauwen-Hinderling, V. B., Mensink, M., Lenaers, E., Meex, R., Hoeks, J., Kooi, M. E., Moonen-Kornips, E., Sels, J.-P., Hesselink, M. K. C., & Schrauwen, P. (2008). Lower intrinsic ADP-stimulated mitochondrial respiration underlies in vivo mitochondrial dysfunction in muscle of male type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes, 57(11), 2943-2949. [CrossRef]

- Poulton, J., Luan, J., Macaulay, V., Hennings, S., Mitchell, J., & Wareham, N. J. (2002). Type 2 diabetes is associated with a common mitochondrial variant: Evidence from a population-based case-control study. Human Molecular Genetics, 11(13), 1581-1583. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R. B., & Groop, L. (2015). Genetics of Type 2 Diabetes—Pitfalls and Possibilities. Genes, 6(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Ptitsyn, A., Hulver, M., Cefalu, W., York, D., & Smith, S. R. (2006). Unsupervised clustering of gene expression data points at hypoxia as possible trigger for metabolic syndrome. BMC Genomics, 7, 318. [CrossRef]

- Rambani, V., Hromnikova, D., Gasperikova, D., & Skopkova, M. (2022). Mitochondria and mitochondrial disorders: An overview update. Endocrine Regulations, 56(3), 232-248. [CrossRef]

- Ritov, V. B., Menshikova, E. V., He, J., Ferrell, R. E., Goodpaster, B. H., & Kelley, D. E. (2005). Deficiency of subsarcolemmal mitochondria in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes, 54(1), 8-14. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Pesini, E., Mishmar, D., Brandon, M., Procaccio, V., & Wallace, D. C. (2004). Effects of Purifying and Adaptive Selection on Regional Variation in Human mtDNA. Science, 303(5655), 223-226. [CrossRef]

- Sangwung, P., Petersen, K. F., Shulman, G. I., & Knowles, J. W. (2020). Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Insulin Resistance, and Potential Genetic Implications. Endocrinology, 161(4), bqaa017. [CrossRef]

- Santander-Lucio, H., Totomoch-Serra, A., Muñoz, M. de L., García-Hernández, N., Pérez-Ramírez, G., Valladares-Salgado, A., & Pérez-Muñoz, A. A. (2023). Variants in the Control Region of Mitochondrial Genome Associated with type 2 Diabetes in a Cohort of Mexican Mestizos. Archives of Medical Research, 54(2), 113-123. [CrossRef]

- Schrauwen, P., & Hesselink, M. K. C. (2004). Oxidative capacity, lipotoxicity, and mitochondrial damage in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes, 53(6), 1412-1417. [CrossRef]

- Schrauwen-Hinderling, V. B., Kooi, M. E., Hesselink, M. K. C., Jeneson, J. a. L., Backes, W. H., van Echteld, C. J. A., van Engelshoven, J. M. A., Mensink, M., & Schrauwen, P. (2007). Impaired in vivo mitochondrial function but similar intramyocellular lipid content in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and BMI-matched control subjects. Diabetologia, 50(1), 113-120. [CrossRef]

- Sikhayeva, N., Iskakova, A., Saigi-Morgui, N., Zholdybaeva, E., Eap, C.-B., & Ramanculov, E. (2017). Association between 28 single nucleotide polymorphisms and type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Kazakh population: A case-control study. BMC Medical Genetics, 18(1), 76. [CrossRef]

- Silverman, B. W. (1981). Using Kernel Density Estimates to Investigate Multimodality. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 43(1), 97-99. [CrossRef]

- Soini, H. K., Moilanen, J. S., Finnila, S., & Majamaa, K. (2012). Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation in Finnish patients with matrilineal diabetes mellitus. BMC Research Notes, 5(1), 350. [CrossRef]

- Stump, C. S., Short, K. R., Bigelow, M. L., Schimke, J. M., & Nair, K. S. (2003). Effect of insulin on human skeletal muscle mitochondrial ATP production, protein synthesis, and mRNA transcripts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 100(13), 7996-8001. [CrossRef]

- Sudoyo, H., Suryadi, H., Sitorus, N., Soegondo, S., Pranoto, A., & Marzuki, S. (2003). Mitochondrial Genome and Susceptibility to Diabetes Mellitus. En S. Marzuki, J. Verhoef, & H. Snippe (Eds.), Tropical Diseases: From Molecule to Bedside (pp. 19-36). Springer US. [CrossRef]

- Swan, E. J., Salem, R. M., Sandholm, N., Tarnow, L., Rossing, P., Lajer, M., Groop, P. H., Maxwell, A. P., McKnight, A. J., & Consortium, the G. (2015). Genetic risk factors affecting mitochondrial function are associated with kidney disease in people with Type 1 diabetes. Diabetic Medicine, 32(8), 1104-1109. [CrossRef]

- Szendroedi, J., Schmid, A. I., Chmelik, M., Toth, C., Brehm, A., Krssak, M., Nowotny, P., Wolzt, M., Waldhausl, W., & Roden, M. (2007). Muscle mitochondrial ATP synthesis and glucose transport/phosphorylation in type 2 diabetes. PLoS Medicine, 4(5), e154. [CrossRef]

- Tabebi, M., Charfi, N., Kallabi, F., Alila-Fersi, O., Ben Mahmoud, A., Tlili, A., Keskes-Ammar, L., Kamoun, H., Abid, M., Mnif, M., & Fakhfakh, F. (2017). Whole mitochondrial genome screening of a family with maternally inherited diabetes and deafness (MIDD) associated with retinopathy: A putative haplotype associated to MIDD and a novel MT-CO2 m.8241T>G mutation. Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications, 31(1), 253-259. [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.-L., Zhou, X., Li, X., Zhao, L., & Liu, F. (2006). Variation of mitochondrial gene and the association with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a Chinese population. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 73(1), 77-82. [CrossRef]

- Tawata, M., Hayashi, J. I., Isobe, K., Ohkubo, E., Ohtaka, M., Chen, J., Aida, K., & Onaya, T. (2000). A new mitochondrial DNA mutation at 14577 T/C is probably a major pathogenic mutation for maternally inherited type 2 diabetes. Diabetes, 49(7), 1269-1272. [CrossRef]

- Tawata, M., Ohtaka, M., Iwase, E., Ikegishi, Y., Aida, K., & Onaya, T. (1998). New mitochondrial DNA homoplasmic mutations associated with Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes, 47(2), 276-277. [CrossRef]

- Torroni, A., Achilli, A., Macaulay, V., Richards, M., & Bandelt, H.-J. (2006). Harvesting the fruit of the human mtDNA tree. Trends in Genetics, 22(6), 339-345. [CrossRef]

- Umetsu, K., & Yuasa, I. (2005). Recent progress in mitochondrial DNA analysis. Legal Medicine, 7(4), 259-262. [CrossRef]

- van Oven, M., & Kayser, M. (2009). Updated comprehensive phylogenetic tree of global human mitochondrial DNA variation. Human Mutation, 30(2), E386-E394. [CrossRef]

- Vringer, E., & Tait, S. W. G. (2023). Mitochondria and cell death-associated inflammation. Cell Death & Differentiation, 30(2), Article 2. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., Taniyama, M., Suzuki, Y., Katagiri, T., & Ban, Y. (2001). Association of the mitochondrial DNA 5178A/C polymorphism with maternal inheritance and onset of type 2 diabetes in Japanese patients. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes: Official Journal, German Society of Endocrinology [and] German Diabetes Association, 109(7), 361-364. [CrossRef]

- Weksler-Zangen, S. (2022). Is Type 2 Diabetes a Primary Mitochondrial Disorder? Cells, 11(10), Article 10. [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.-H., Sze-To, H.-Y., Lo, L.-Y., Chan, T.-M., & Leung, K.-S. (2015). Discovering Binding Cores in Protein-DNA Binding Using Association Rule Mining with Statistical Measures. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Computational Biology and Bioinformatics, 12(1), 142-154. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-M., Li, T., Wang, Z.-F., Huang, S.-S., Shao, Z.-Q., Wang, K., Zhong, H.-Q., Chen, S.-F., Zhang, X., & Zhu, J.-H. (2018). Mitochondrial DNA variants modulate genetic susceptibility to Parkinson’s disease in Han Chinese. Neurobiology of Disease, 114, 17-23. [CrossRef]

- Yang, B. T., Dayeh, T. A., Volkov, P. A., Kirkpatrick, C. L., Malmgren, S., Jing, X., Renström, E., Wollheim, C. B., Nitert, M. D., & Ling, C. (2012). Increased DNA Methylation and Decreased Expression of PDX-1 in Pancreatic Islets from Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Molecular Endocrinology, 26(7), 1203-1212. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B., Lu, Y., Hajifathalian, K., Bentham, J., Cesare, M. D., Danaei, G., Bixby, H., Cowan, M. J., Ali, M. K., Taddei, C., Lo, W. C., Reis-Santos, B., Stevens, G. A., Riley, L. M., Miranda, J. J., Bjerregaard, P., Rivera, J. A., Fouad, H. M., Ma, G., … Cisneros, J. Z. (2016). Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: A pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4·4 million participants. The Lancet, 387(10027), 1513-1530. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).