1. Introduction

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the SARS-CoV-2 virus has evolved very rapidly, giving rise to a series of mutations, generating multiple variants of concern (VOCs) like Beta, Delta, and, subsequently, Omicron [

1]. Within the Omicron lineage, recombinant strains have emerged constantly starting from the earliest BA.1 strain to the latest XBB.1.5, XBB 1.16, and EG.5.1 strains. As of August 2023, these Omicron subvariants appear to have become dominant worldwide. XBB lineages have likely evolved from a recombination event among two BA.2 strains with a mutation at S486P [

2]. The additional F486P substitution in XBB.1.5 is believed to offer higher affinity to the human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) receptor than seen with BQ.1, XBB, and XBB.1 [

3]. As a consequence, immunization or prior exposure to the ancestral wild-type (WT) variant provides suboptimal protection through neutralizing antibodies [

4]. Specifically, studies have shown that XBB and other Omicron strains such as BQ.1.1 have higher resistance to humoral immunity induced by vaccination or natural infection, than earlier strains like BA.2 and BA.5 [

5,

6,

7]. These findings were confirmed with our recombinant protein vaccines, either RBD219-N1 or RBD203-N1, which encodes the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. In mice and non-human primates, such RBDs, adjuvanted with CpG oligonucleotides and aluminum hydroxide (alum) induced high neutralizing antibodies (Abs) against SARS-CoV-2 (WT) [

8,

9,

10]. Such antigens became central components of the Corbevax vaccine produced by Biological E in India and IndoVac produced by BioFarma in Indonesia and have been administered close to 100 million times [

11].

While these vaccines still offer protection from severe disease, the cross-neutralizing titers against the Omicron strains are suboptimal. As XBB.1.5 is highly resistant to antiviral immunotherapy, the most efficient way to control the current wave is to update vaccine antigens to induce a more effective immunity [

12]. Here, we show the development and testing of an XBB.1.5 RBD-based vaccine together with vaccines matching the Beta, Delta, and BA.4/5 variants. We used pseudovirus neutralization assays to determine the cross-protection elicited by these antigens against the ancestral strain (WT), and eight additional variants (Beta, Delta, BA.4, BQ.1.1, BA.2.75.2, XBB.1.16, XBB.1.5 and EG.5.1).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sources of recombinant RBD203-N1 proteins

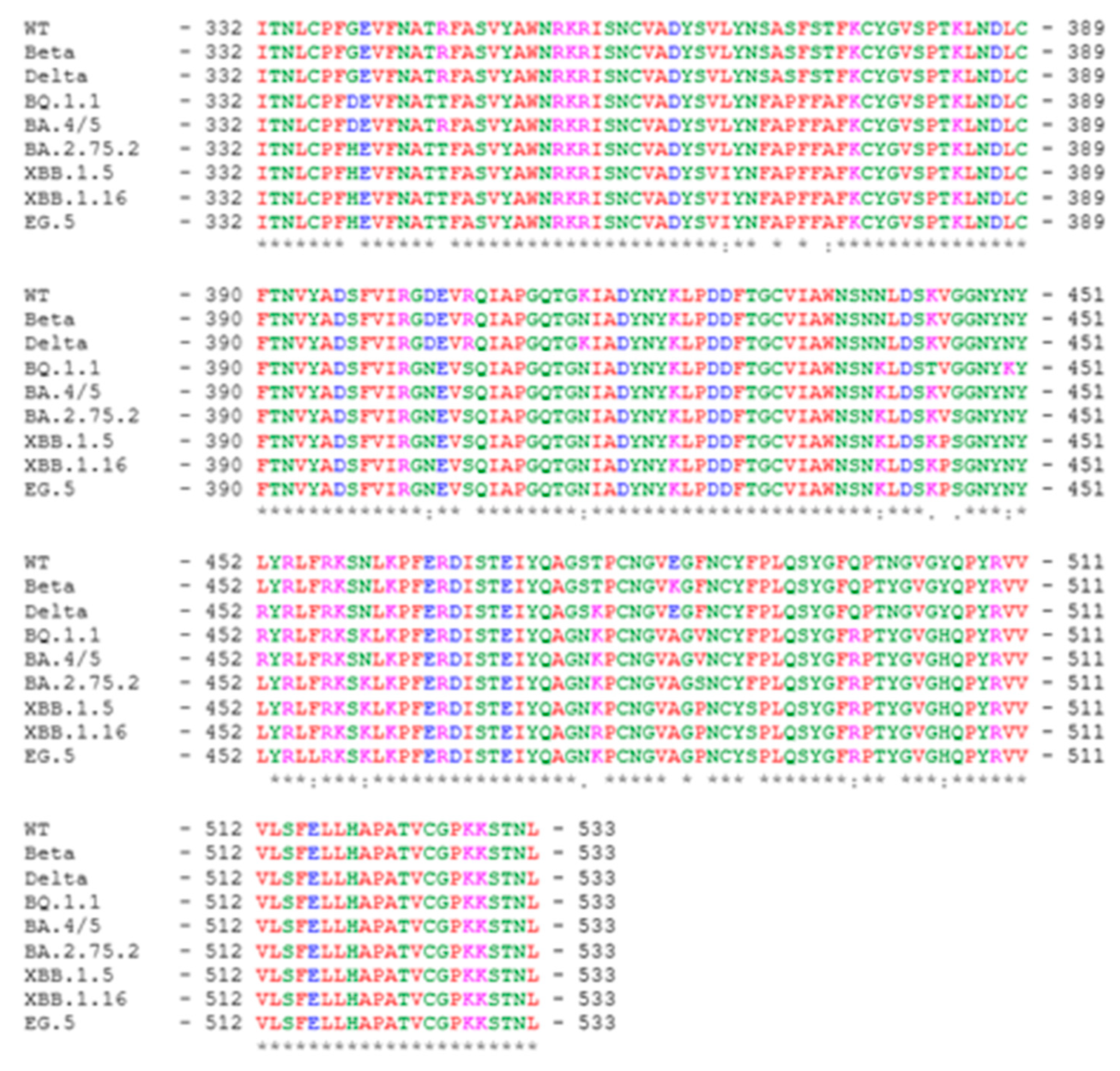

SARS-CoV-2 RBD203-N1 protein was designed and produced as previously described [

8,

13], and it encompasses amino acid residues 332-533 of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. The sequence alignment among the RBD variants included in this study is shown in

Figure 1.

2.2. Production of the five variant RBD antigens in Pichia pastoris X-33

To generate the recombinant proteins in yeast, DNAs encoding the SARS-CoV-RBD203-N1 proteins for the WT, Beta, Delta, Omicron BA.4/5 (BA.4 RBD is identical to BA.5), and XBB.1.5 variants were codon-optimized based on yeast codon preference and cloned into the yeast expression vector pPICZαA. The recombinant plasmid DNAs were transformed into

P. pastoris X33 following a process described previously [

8,

14]. The highest expressing clones for each RBD were used to make research seed stocks that were saved at –80 °C. Fermentation was carried out at the 5 or 1 L scale, respectively, as previously described [

14]. Briefly, the seed stocks for each construct were used to inoculate a 0.5 L buffered minimal glycerol (BMG) medium and were grown at 30 °C and 250 rpm until an OD600 of 5–10. This culture was used to inoculate sterile low-salt medium (LSM, pH 5.0) with PTM1 trace elements and d-Biotin. Cell expansion was continued at 30 °C with a dissolved oxygen (DO) set point of 30% until glycerol depletion. Then methanol was pumped in from 1 mL/L/h to 11 mL/L/h over a 6 h period; the pH was adjusted to 6.5. The methanol induction was maintained at 11 mL/L/h at 25 °C for 70 h, except for XBB.1.5-RBD which was induced for 48 h. After fermentation, the culture was harvested by centrifugation, filtered, and kept frozen at −80 °C until purification. The recombinant RBD protein was captured from the fermentation supernatant using a butyl Sepharose high-performance column (Cytiva) in the presence of ammonium sulfate salt at a concentration of 0.8 M (XBB.1.5-RBD) or 1.1 M (WT-RBD, Beta-RBD, Delta-RBD and BA.4/5-RBD) in HIC buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0). RBD protein was further purified using a Q Sepharose XL (QXL) column (Cytiva) in a negative mode in QXL buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5) with 100 mM NaCl (WT-RBD and Beta-RBD), 50 mM NaCl (Delta-RBD) or 0 mM NaCl (XBB.1.5-RBD). For BA.4/5-RBD, a negative QXL chromatography was performed in QXL buffer B (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.4 and 10 mM NaCl) followed by dialysis in QXL buffer C (20 mM L-histidine and 100 mM NaCl, pH 6.0) for storage. All RBD proteins were aseptically filtered using a 0.22 µm filter and stored at -80 °C until usage. To evaluate these RBD proteins’ biophysical characteristics and functionality, SDS-PAGE-based densitometry, dynamic light scattering, and ACE-2 binding assays were performed following the methods previously described [

15]. Size Exclusion High Pressure Chromatography (SE-HPLC) was performed by injecting 50 µg of RBD on an XBridge Premier Protein SEC Column (Waters, Cat# 186009959) connected with a corresponding guard column (Waters, Cat# 186009969). The protein was eluted with 1X TBS, pH 7.5 at a 0.5 mL/min flow rate. The Bio-Rad gel filtration standard (Bio-Rad, catalog# 1511901) was used as a control.

2.3. Vaccine formulations and preclinical study design

Animals were housed and provided care in strict adherence to the guidelines set forth by local, state, federal, and institutional policies. Facilities were accredited by AAALAC International, meeting the standards outlined in the Animal Welfare Act and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Experiments were performed under a Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocol. Female BALB/c mice (N=8/group), aged 6-8 weeks old, were immunized twice intramuscularly at 21-day intervals with the antigens shown in Table S1 and then euthanized two weeks after the second vaccination. Each dose of the SARS-CoV-2 RBD vaccine contained 7 µg RBD protein, 200 µg alum (Alhydrogel®, aluminum hydroxide, Catalog # AJV3012, Croda Inc., UK), and 20 µg CpG1826 (Invivogen, USA). The SARS-CoV-2 RBD proteins were prepared with 1xTBS buffer (20 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.5). Before injection, alum and CpG 1826 were added, and the sample was vortexed for 3 s.

2.4. Serological antibody measurements by ELISA

To examine SARS-CoV-2 RBD-specific antibodies in the mouse sera, indirect ELISAs were conducted as published before [

13]. Briefly, plates were coated with 0.2 µg/well of SARS-CoV-2 RBD proteins from different variants. Mouse sera samples were 3-fold diluted from 1:200 to 1: 11,809,800 in 0.1% BSA in assay buffer (0.05% Tween20 in 1x PBS). Samples were prepared and measured in duplicate. Assay controls included a 1:400 dilution of pooled naïve mouse sera (negative control) 1:10,000 dilution of pooled high titer mouse (positive control) and assay buffer as blanks. 100 µL/well of 1:6000 goat anti-mouse IgG HRP, in assay buffer was added. After incubation, plates were washed five times, followed by adding 100 µL/well of TMB substrate. Plates were incubated for 15 min at room temperature (RT) while protected from light. After incubation, the reaction was stopped by adding 100 µL/well 1 M HCl. The absorbance at a wavelength of 450 nm was measured using a BioTek Epoch 2 spectrophotometer. For each sample, the titer was determined using a four-parameter logistic regression curve of the absorbance values. The titer cutoff value: negative serum control + 3 x standard deviation of the negative serum control.

2.5. Pseudovirus assay for determination of neutralizing antibodies

To test for neutralizing antibodies, we prepared non-replicating lentiviral particles expressing the SARS-CoV-2 spike variant proteins on their membrane and encoding luciferase as a reporter. Infection was quantified using in vitro-grown human 293 T-hACE-2 cells based on luciferase expression. The pseudovirus production system included the luciferase-encoding reporter plasmid, pNL4-3. lucR-E-, a Gag/Pol-encoding packaging construct (pΔ8.9), and the codon-optimized SARS-CoV-2 spike VOC-expressing plasmids (pcDNA3.1-CoV-2 S gene), based on clone p278-1 [

13]. Pseudovirus-containing supernatants were recovered 48 h after transfection, passed through a 0.45 µm filter and saved at −80 °C until used for neutralization studies.

Expression plasmids for SARS-CoV-2 spike variants of concern WT, Beta, and Delta were generated by site-directed mutagenesis or replacement of segments of the codon-optimized Wuhan SARS-CoV-2 spike expression clone, p278-1 with variant sequences as previously described [

8]. Omicron spike variants BA.4, BA.2.75.2, BQ.1.1, XBB.1.5, and EG.5 sequences were generated by changing codons of the p278-1 spike clone sequence to produce the consensus amino acid sequence of each variant. The variant spike sequences were synthesized with the 3’ Flag-tag (

Genscript) and inserted into the pcDNA3.1 expression vector. The list with the variant-specific mutations added to the spike protein variant clones can be found in the supplementary data. The sequences of all the variant spike genes were confirmed by commercial DNA sequencing.

The pseudovirus assay was performed as described earlier [

13]. Briefly, 10 μL of pseudovirus were incubated with serial dilutions of the serum samples for 1 h at 37 °C. Next, 100 µL of sera-pseudovirus were added to 293 T-hACE-2 cells in 96-well poly-D-lysine coated culture plates. Following 48 h of incubation in a 5% CO

2 environment at 37 °C, the cells were lysed with 100 µL of Promega Glo Lysis buffer for 15 min at room temperature. Finally, 50 µL of the lysate was added to 50 µL luciferase substrate (Promega Luciferase Assay System). The amount of luciferase was quantified by luminescence (relative luminescence units (RLU)), using the Luminometer (

Biosynergy H4, BioTek). Pooled sera from vaccinated mice (n=8) were compared by their 50% inhibitory dilution (IC50), defined as the serum dilution at which the virus infection was reduced by 50% compared to the negative control (virus + cells). IC50 values were calculated as described by Nie

et al. [

16]. Samples were measured in duplicate. Statistical analyses were performed on sets of IC50 titers elicited by sera from mice vaccinated with each of the RBD vaccines against s pseudovirus variants using GraphPad Prism 8.0 to rank the RBD vaccines according to Spearman’s correlation coefficient.

3. Results

3.1. Expression, purification, and characterization of recombinant proteins of different variants of SARS-CoV-2 RBD203

After

P. pastoris X-33 plasmid transformation, recombinant proteins of different variants of the SARS-CoV-2 RBD, including WT, Beta, Delta, Omicron BA.4/5 and Omicron XBB.1.5, were expressed by induction with methanol at 30 °C for 72 hours (WT, Beta, Delta, BA.4/5) or 48 hours (XBB.1.5) in either a 1 or a 5 L fermentation process. Following the published protocol for RBD203-N1 [

14], all proteins were purified by a combination of a hydrophobic interaction and ion exchange chromatography. While all proteins were purified to more than 96% homogeneity, their yields differed (

Table 1). In particular, the RBDs of the two Omicron strains, BA.4/5 and XBB.1.5 showed reduced yields. We are currently optimizing the purification conditions of these strains to prepare for technology transfer to manufacturing partners.

When analyzed by SE-HPLC, all RBD proteins produced a single peak detected at UV280 nm, confirming the homogeneity of each preparation (

Figure 2A). Moreover, the apparent molecular weight by SE-HPLC matched that observed by densitometry scanning of SDS-PAGE gels (

Table 1).

The functionality of the purified RBD molecules was established in an ACE-2 binding assay (

Figure 2B), where all proteins were shown to bind recombinant human ACE-2. Consistent with prior data published by Mannar

et al. [

17], the affinity of the Omicron RBDs seemed to be higher than the other RBD variants, while the WT-RBD possessed the lowest binding affinity to ACE-2.

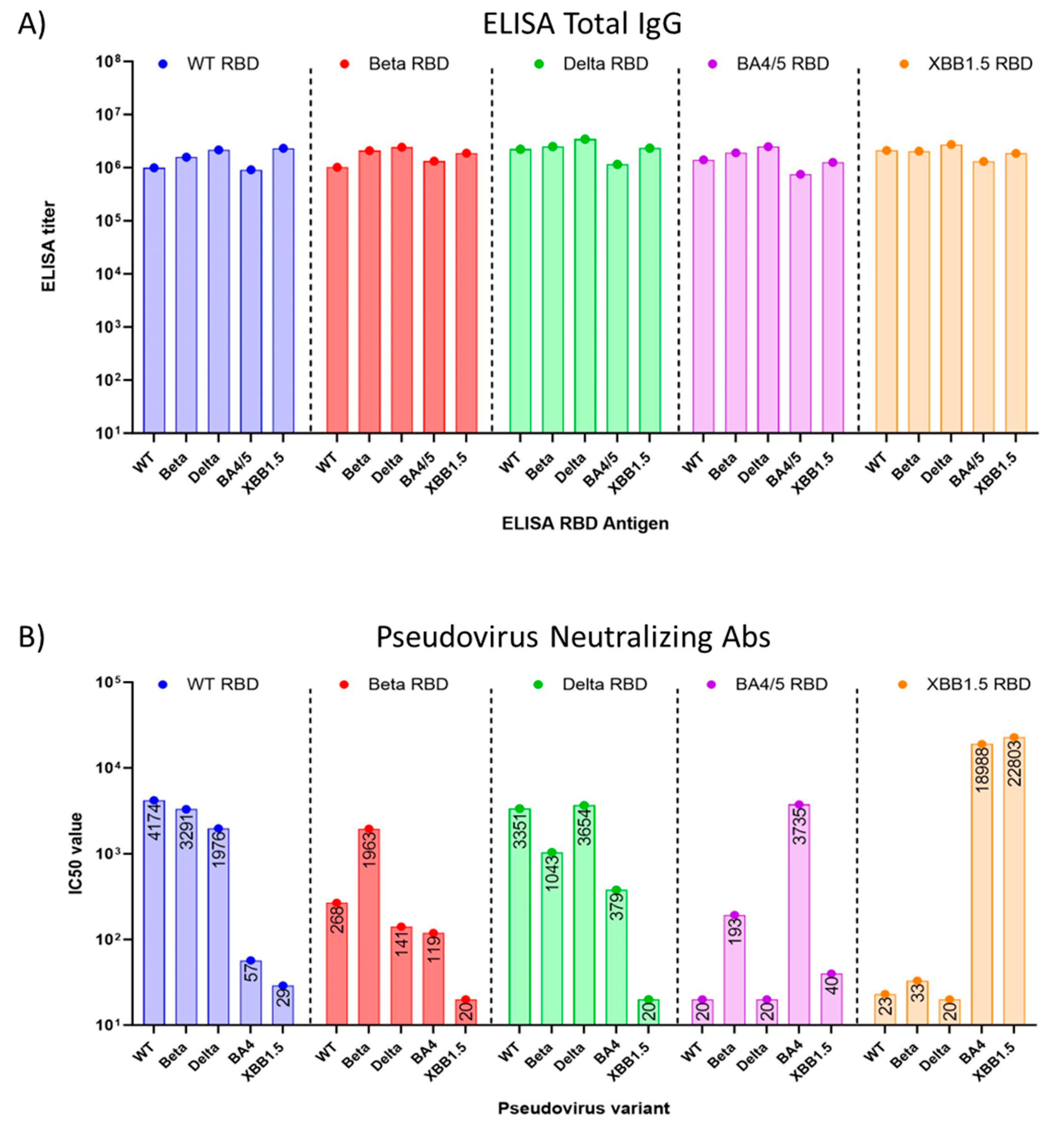

3.2. Immune response induced by adjuvanted RBD vaccines in mice

Preclinical studies were performed in eight to nine-week-old female BALB/c mice, using yeast-produced SARS-CoV-2 recombinant RBD proteins, adjuvanted with aluminum hydroxide and CpG1826. Mice (n=8/group) were immunized twice intramuscularly on days 0 and 21 with a dose of 7 µg RBD, 200 µg alum, and 20 µg CpG. On day 35, the study was terminated, and sera were collected and evaluated for total RBD-specific IgG and neutralizing antibodies against pseudoviruses matching the WT SARS-CoV-2 isolate, Beta, Delta, as well as the Omicron variants BA.4 and XBB.1.5 and XBB.1.16 (

Figure 3).

We found that the total RBD-specific IgG antibody titers elicited in mouse sera by all five (WT, Beta, Delta, BA.4/5, and XBB.1.5) RBDs were high when tested with immobilized antigens in an ELISA. (

Figure 3A). However, when sera were tested for neutralizing antibodies in a pseudovirus assay, we observed that cross-protection of WT RBD-induced sera against Omicron BA.4/5 pseudovirus was minimal

(Figure 3B), with a 73-fold reduction in the IC50 from 4174 against WT pseudovirus, to an IC50 of 57 against BA.4/5 pseudovirus. The titer against Omicron XBB.1.5 pseudovirus was even lower, with an IC50 of 29. Nab titers induced by Beta RBD and Delta RBD also failed to suggest protection against Omicron XBB.1.5 pseudovirus (

Figure 3B). However, sera raised against the BA.4/5 RBD showed no protection against WT (IC50=20), Beta (IC50=193), Delta (IC50=20) pseudoviruses, and notably, the sera offered little protection against XBB.1.5 (IC50=40) pseudoviruses. Mice vaccinated with the XBB.1.5 RBD vaccine showed low neutralizing antibody titers against the WT, Beta, and Delta pseudoviruses [

18]. By contrast, they demonstrated high titers of neutralizing antibodies against the Omicron BA.4 and XBB.1.5 pseudoviruses. Interestingly, protection against BA.4/5 pseudovirus was even more pronounced with the XBB.1.5 vaccine than with the homologous antigen (

Figure 3B), an observation that is similar to what was seen in the high anti-BA.4/5 neutralizing antibody titers generated by the Moderna XBB.1.5 vaccine [

19].

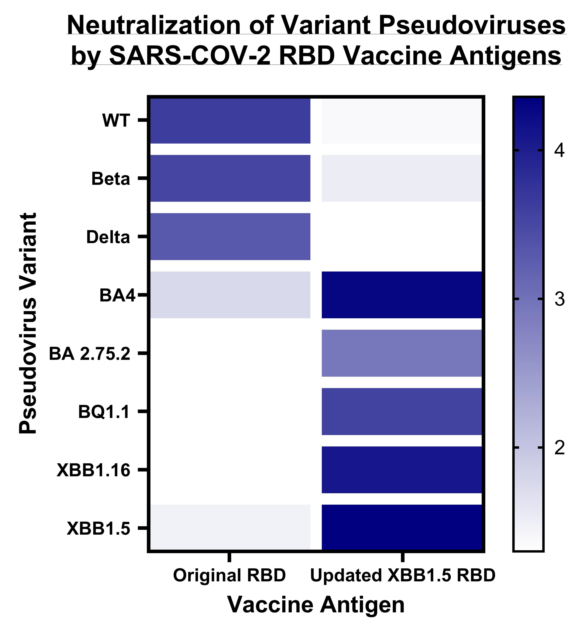

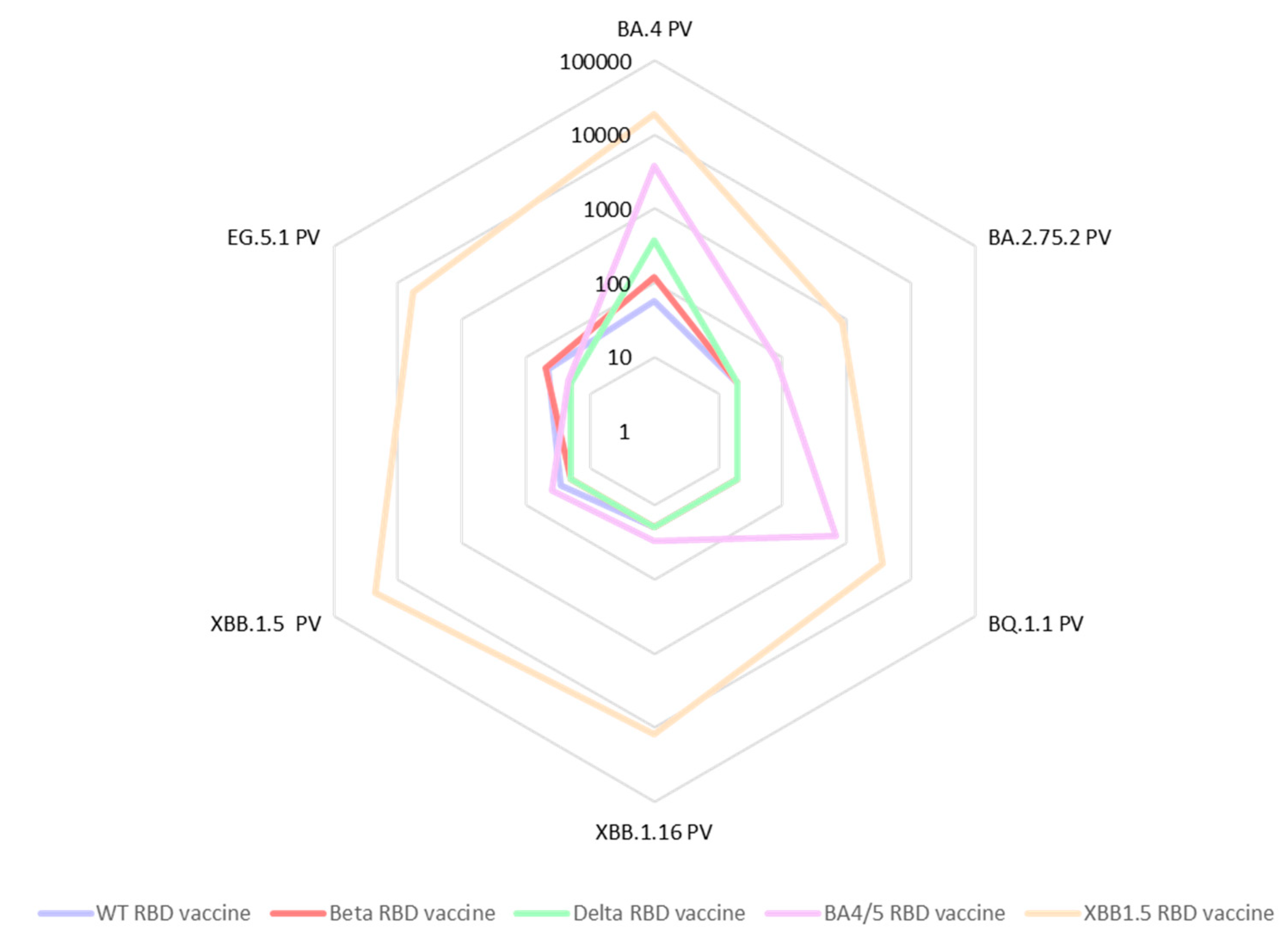

In a further expansion of our cross-neutralization studies, we tested the same sera against the Omicron pseudoviruses: BA.2.75.2, BQ.1.1, BA.4, XBB.1.5, XBB.1.16 as well as EG.5.1 (

Figure 4). We observed a significant deficiency in cross-neutralization for most of the mouse sera from animal vaccinated with either RBD WT, RBD Beta, or RBD Delta when confronted with the Omicron variants. Notably, even for sera from mice vaccinated with the BA.4/5 vaccine, evidence of immune evasion was observed. These results are in accordance with data reported by other researchers [

18]. In contrast, the sera from mice vaccinated with the updated vaccine comprising the XBB.1.5-RBD antigen exhibited exceptional cross-neutralization capabilities against all tested Omicron spike pseudoviruses. Particularly encouraging was the remarkably high IC50 value (IC50=5,758) exhibited by the XBB1.5 sera against the EG.5.1 pseudovirus. This is especially significant as EG.5.1 is among the current emerging variants of concern, rapidly spreading worldwide.

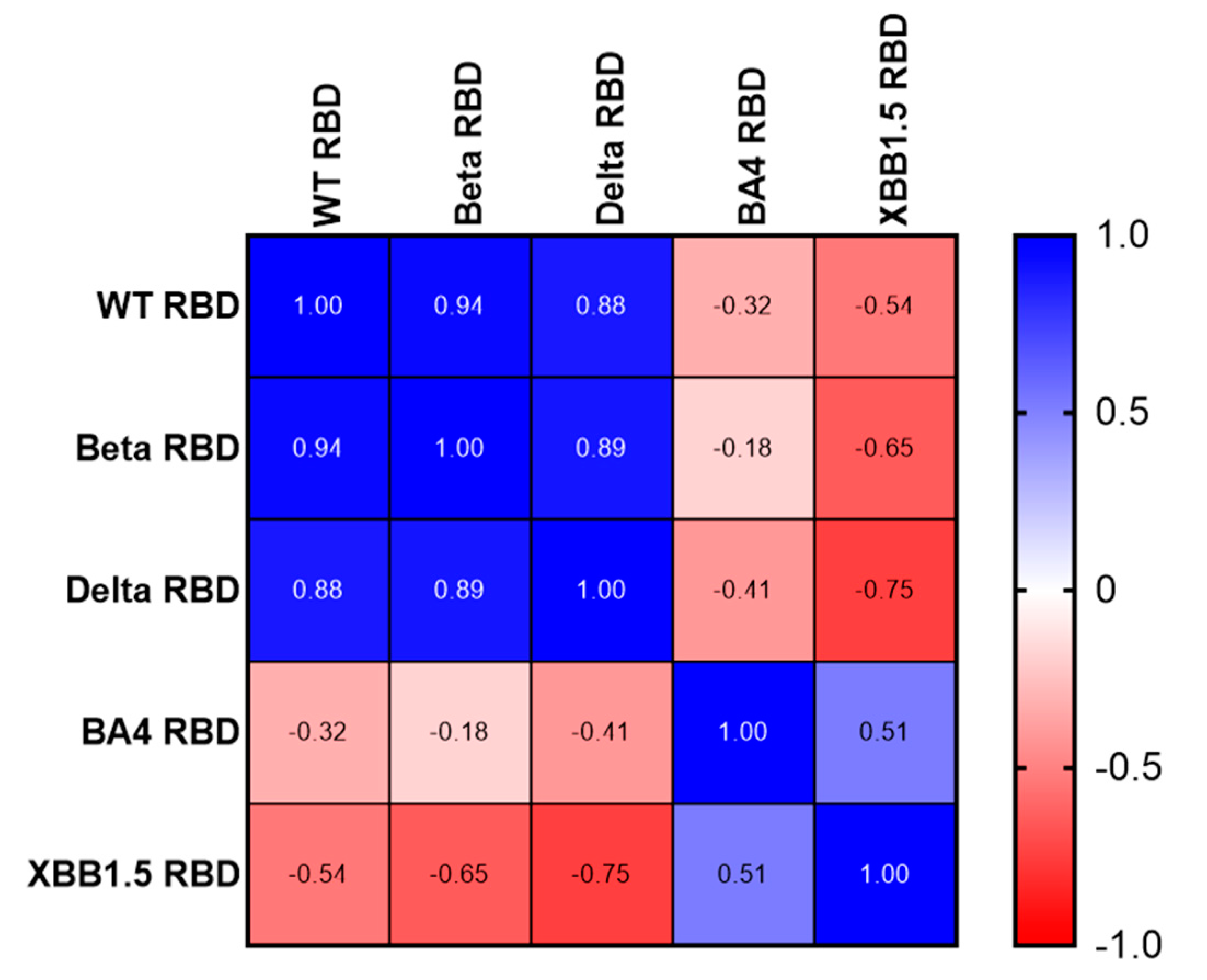

Using a Spearman correlation on the IC50 values, we illustrate the number of different neutralizing epitopes comparing the RBD antigens of SARS-CoV variants. While we noticed a positive gradient of similarity (

Figure 5, Blue) among the RBDs of three earlier variants of concern (WT, Beta, and Delta), we found a negative correlation coefficient value comparing WT, Beta, Delta RBDs to Omicron BA.4/5 and XBB.1.5 RBDs (

Figure 5, Red). Likewise, Omicron RBD BA.4/5 and XBB.1.5 share many neutralizing epitopes, while no correlation was found with the earlier RBDs.

4. Discussion

In the fourth year of the pandemic, immune escape variants of SARS-CoV-2 continue to pose a significant threat to global health. Omicron variants such as BA.2.75.2, BQ.1.1, XBB.1.5, XBB.1.16, and EG.5.1 are characterized by a large number of mutations with increased transmissibility and more pronounced immune evasion. As these new variants emerge, intra-VOC recombination events are commonly observed, leading to an ever-increasing cascade of sub-lineages. Current data indicates that the XBB.1.5 strain is highly resistant to monoclonal antibodies and convalescent plasma treatment [

7,

20]. The XBB subvariant’s high transmissibility and its high number of mutations likely have contributed to immune evasion. Thus, the vaccines that only targeted the ancestral virus are not as successful in raising neutralizing antibodies against more recent subvariants. In addition, bivalent boosters that contain both ancestral and BA.4/5 antigens are poorly neutralizing against Omicron-derived next-generation subvariants, including XBB.1.5 [

21]. Therefore, the broader neutralizing immune response generated by the XBB.1.5 antigen against additional Omicron subvariants in this study is encouraging for protection against current circulating strains and potential future variants.

In this study, we compared the efficacy of various vaccines based on the RBD of variant SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins, with the goal of better characterizing cross-neutralization. We observed minimal heterologous cross-neutralization of the XBB.1.5 pseudovirus with immune sera generated with vaccines based on RBDs of early VOCs. Even immunizations with the more recent BA.4/5 RBD generated only partial cross-neutralization of the XBB.1.5 pseudovirus. These results mirror findings for breakthrough human infections of BA.4 which did not generate adequate cross-neutralizing antibodies to protect against XBB subvariants [

21]. Our results also re-emphasized that, as compared to the cross-neutralization of the earlier three variants (i.e. WT, Beta, and Delta), Omicron variants have evolved enough to successfully escape neutralization by parental vaccines. This was exemplified by the neutralization data from WT, Beta, and Delta RBD vaccinations against both BA.4 and XBB.1.5 pseudoviruses in this study. Importantly, the IgG antibody binding data from ELISAs demonstrated that vaccination with each of the ancestral RBDs (i.e. WT, Beta, and Delta) induced high levels of IgG that could recognize all five of the different RBDs, including BA.4/5 and XBB.1.5. Yet, the sera had low functional neutralizing antibody titers against the BA.4/5 and XBB variant pseudoviruses. We acknowledge that no live virus neutralization assays have yet been conducted with the XBB.1.5 vaccine. However, in our previous publication introducing an earlier version of the RBD vaccine [

22], we have shown that generally our pseudovirus assay is very well correlated with the live virus PRNT assay (R

2=0.9274). We also note that the WHO and others have shown excellent comparability between pseudovirus and live virus assays [

23,

24].

In addition to the reported immune imprinting caused by previous vaccinations [

19], the antigenic diversities caused by mutations on spike proteins [

25] between a variety of Omicron sub-variants may further dampen the neutralization process and reduce the immune response against future variants. This is especially true in the case of XBB sub-lineages where the neutralizing antibodies elicited against XBB sub-variants were very low after BA.5 infection, indicating the evolution of the XBB sub-lineage further away from BA.4/5 [

21]. We have observed weak cross-neutralization from BA.4/5 RBD generated sera against XBB.1.5 and XBB.1.16 subvariants, while the inverse combination of XBB.1.5 RBD antigen against BA.4/5 pseudovirus offered very strong neutralizing antibody titers. The current study shows the value of the XBB.1.5 RBD antigen with its increased number of mutations in its RBD as a better vaccine candidate with successful cross-neutralization capacity against all subvariants of Omicron such as BA.4/5, BA.2.75, BQ.1.1, XBB.1.16, XBB.1.5 as well as against the most recent COVID-19 variants such as EG.5.1.

As the 2023 fall respiratory season approaches, we are seeing an uptick in illnesses caused by the Omicron variant EG.5 or ‘Eris’, and cases could continue to rise [

26]. The spike protein of EG.5 shares an almost identical amino acid profile with XBB.1.5, distinguishing itself with an additional F456L amino acid mutation. Within the EG.5 lineage, EG.5.1 is the dominant subvariant (more than 88% of cases) [

27], which is characterized by an additional spike mutation: Q52H. At the end of August 2023, EG.5 had been linked to 20.6% of COVID-19 cases in the United States, surpassing all other circulating SARS-CoV-2 strains in prevalence [

27]. Our data strongly indicate that the RBD XBB1.5 vaccine provides effective protection against the EG.5.1 strain of the SARS-CoV-2 virus through the production of neutralizing antibodies. Such levels of neutralization against those same variants were not imparted by the BA.4/5 RBD vaccine, underscoring the importance of developing the next generation of COVID-19 vaccines customized towards XBB subvariant sequences. Further experiments will focus on using an XBB.1.5 boost after vaccination with the WT and BA.4/5 RBDs to mimic the real-world scenario and yield valuable information about the cross-protection levels against current and potential future versions of XBB derivatives. In addition, we believe that our observation of broad protection levels of the XBB.1.5 vaccine is likely also applicable to the updated mRNA vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna that also express the XBB.1.5 antigen [

12], and which are becoming available to the general public in the United States of America by the end of September 2023.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: SRT, BK, AC, LV, PMG, BZ, US, MEB, PJH, and JP; methodology: SRT, RA, MJV, JL, ZL, RTK, YC, BK, LV, NYI, CP, NU, WHC, SS, KG, JTK, and BZ; formal analysis: SRT, RA, LV, CP, WHC, RK, JTK, BZ, US, MEB, PJH, and JP; writing—original draft preparation: SRT, JTK, US, and JP; writing—review and editing: SRT, RA, MJV, JL, ZL, RK, YC, BK, PMG, LV, NYI, CP, NU, WHC, SS, KG, JTK, BZ, MEB, PJH, and JP; visualization: SRT, YC, WHC, US, and JP; supervision: JL, ZL, CP, WHC, JTK, BZ, US, MEB, PJH, and JP; project administration: PMG and AC; funding acquisition: MEB and PJH. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the following funding sources: Robert J. Kleberg Jr. and Helen C. Kleberg Foundation, USA; Fifth Generation, Inc., USA; JPB Foundation, USA,); and Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development Intramural Funds, USA. In addition, we gratefully acknowledge donations from various private individuals received in support of our vaccine development program.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their sincere gratitude to Diane Nino and Kay Razavi for their invaluable contributions to the vaccine center's COVID-19 vaccine program. We are grateful to Dr. Vincent Munster (NIAID) for providing the spike expression plasmid for SARS-CoV-2 and thank Dr. Paula Aulicino for many discussions on SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Conflicts of Interest

Several of the authors are co-inventors of a COVID-19 recombinant protein vaccine technology owned by Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) that was licensed by BCM non-exclusively and with no patent restrictions to several companies committed to advancing vaccines for low- and middle-income countries. The co-inventors have no involvement in license negotiations conducted by BCM. Similar to other research universities, a long-standing BCM policy provides its faculty and staff, who make discoveries that result in a commercial license, a share of any royalty income.

References

- A. M. Carabelli et al., “SARS-CoV-2 variant biology: immune escape, transmission and fitness,” Nat Rev Microbiol, vol. 21, no. 3, Art. no. 3, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. K. Channabasappa, A. K. Niranjan, and T. B. Emran, “SARS-CoV-2 variant omicron XBB.1.5: challenges and prospects – correspondence,” Int J Surg, vol. 109, no. 4, pp. 1054–1055, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. Gerardi, M. A. Rohaim, R. F. E. Naggar, M. O. Atasoy, and M. Munir, “Deep Structural Analysis of Myriads of Omicron Sub-Variants Revealed Hotspot for Vaccine Escape Immunity,” Vaccines (Basel), vol. 11, no. 3, p. 668, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Qu et al., “Enhanced evasion of neutralizing antibody response by Omicron XBB.1.5, CH.1.1, and CA.3.1 variants,” Cell Rep, vol. 42, no. 5, p. 112443, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. He et al., “A recombinant spike-XBB.1.5 protein vaccine induces broad-spectrum immune responses against XBB.1.5-included Omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2,” MedComm, vol. 4, no. 3, p. e263, 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Li et al., “Neutralization of BQ.1, BQ.1.1, and XBB with RBD-Dimer Vaccines,” N Engl J Med, vol. 388, no. 12, pp. 1142–1145, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Imai et al., “Efficacy of Antiviral Agents against Omicron Subvariants BQ.1.1 and XBB,” N Engl J Med, vol. 388, no. 1, pp. 89–91, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Pollet et al., “Receptor-binding domain recombinant protein on alum-CpG induces broad protection against SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern,” Vaccine, vol. 40, no. 26, pp. 3655–3663, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Pollet et al., “SARS-CoV-2 RBD219-N1C1: A yeast-expressed SARS-CoV-2 recombinant receptor-binding domain candidate vaccine stimulates virus neutralizing antibodies and T-cell immunity in mice,” Hum Vaccin Immunother, vol. 17, no. 8, pp. 2356–2366, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Pino et al., “A yeast-expressed RBD-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccine formulated with 3M-052-alum adjuvant promotes protective efficacy in non-human primates,” Sci Immunol, vol. 6, no. 61, p. eabh3634. [CrossRef]

- P. J. Hotez et al., “From concept to delivery: a yeast-expressed recombinant protein-based COVID-19 vaccine technology suitable for global access,” Expert Rev Vaccines, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 495–500, 2023. [CrossRef]

- “Statement on the antigen composition of COVID-19 vaccines.” https://www.who.int/news/item/18-05-2023-statement-on-the-antigen-composition-of-covid-19-vaccines (accessed Aug. 18, 2023).

- J. Pollet et al., “SARS-CoV-2 RBD219-N1C1: A yeast-expressed SARS-CoV-2 recombinant receptor-binding domain candidate vaccine stimulates virus neutralizing antibodies and T-cell immunity in mice,” Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, vol. 17, no. 8, pp. 2356–2366, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Lee et al., “Process development and scale-up optimization of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain–based vaccine candidate, RBD219-N1C1,” Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, vol. 105, no. 10, pp. 4153–4165, 2021. [CrossRef]

- W.-H. Chen et al., “Yeast-expressed recombinant SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain RBD203-N1 as a COVID-19 protein vaccine candidate,” Protein Expr Purif, vol. 190, p. 106003, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Nie et al., “Quantification of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody by a pseudotyped virus-based assay,” Nat Protoc, vol. 15, no. 11, Art. no. 11, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Mannar et al., “SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant: Antibody evasion and cryo-EM structure of spike protein-ACE2 complex,” Science, vol. 375, no. 6582, pp. 760–764, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Yamasoba et al., “Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron XBB.1.16 variant,” Lancet Infect Dis, vol. 23, no. 6, pp. 655–656, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Chalkias et al., “Safety and Immunogenicity of XBB.1.5-Containing mRNA Vaccines.” medRxiv, p. 2023.08.22.23293434, Aug. 24, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Uraki et al., “Humoral immune evasion of the omicron subvariants BQ.1.1 and XBB,” The Lancet Infectious Diseases, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 30–32, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Yang et al., “Low levels of neutralizing antibodies against XBB Omicron subvariants after BA.5 infection,” Sig Transduct Target Ther, vol. 8, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Pollet et al., “Receptor-binding domain recombinant protein on alum-CpG induces broad protection against SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern,” Vaccine, vol. 40, no. 26, Art. no. 26, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Sholukh et al., “Evaluation of Cell-Based and Surrogate SARS-CoV-2 Neutralization Assays,” Journal of Clinical Microbiology, vol. 59, no. 10, Art. no. 10, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Riepler et al., “Comparison of Four SARS-CoV-2 Neutralization Assays,” Vaccines (Basel), vol. 9, no. 1, p. 13, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. Wang et al., “Antigenic cartography of well-characterized human sera shows SARS-CoV-2 neutralization differences based on infection and vaccination history,” Cell Host Microbe, vol. 30, no. 12, pp. 1745-1758.e7, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- “What to Know About EG.5 (Eris)—the Latest Coronavirus Strain,” Yale Medicine. https://www.yalemedicine.org/news/covid-eg5-eris-latest-coronavirus-strain (accessed Sep. 24, 2023).

- D. V. Parums, “Editorial: A Rapid Global Increase in COVID-19 is Due to the Emergence of the EG.5 (Eris) Subvariant of Omicron SARS-CoV-2,” Med Sci Monit, vol. 29, pp. e942244-1-e942244-4, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).