Submitted:

30 August 2023

Posted:

06 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

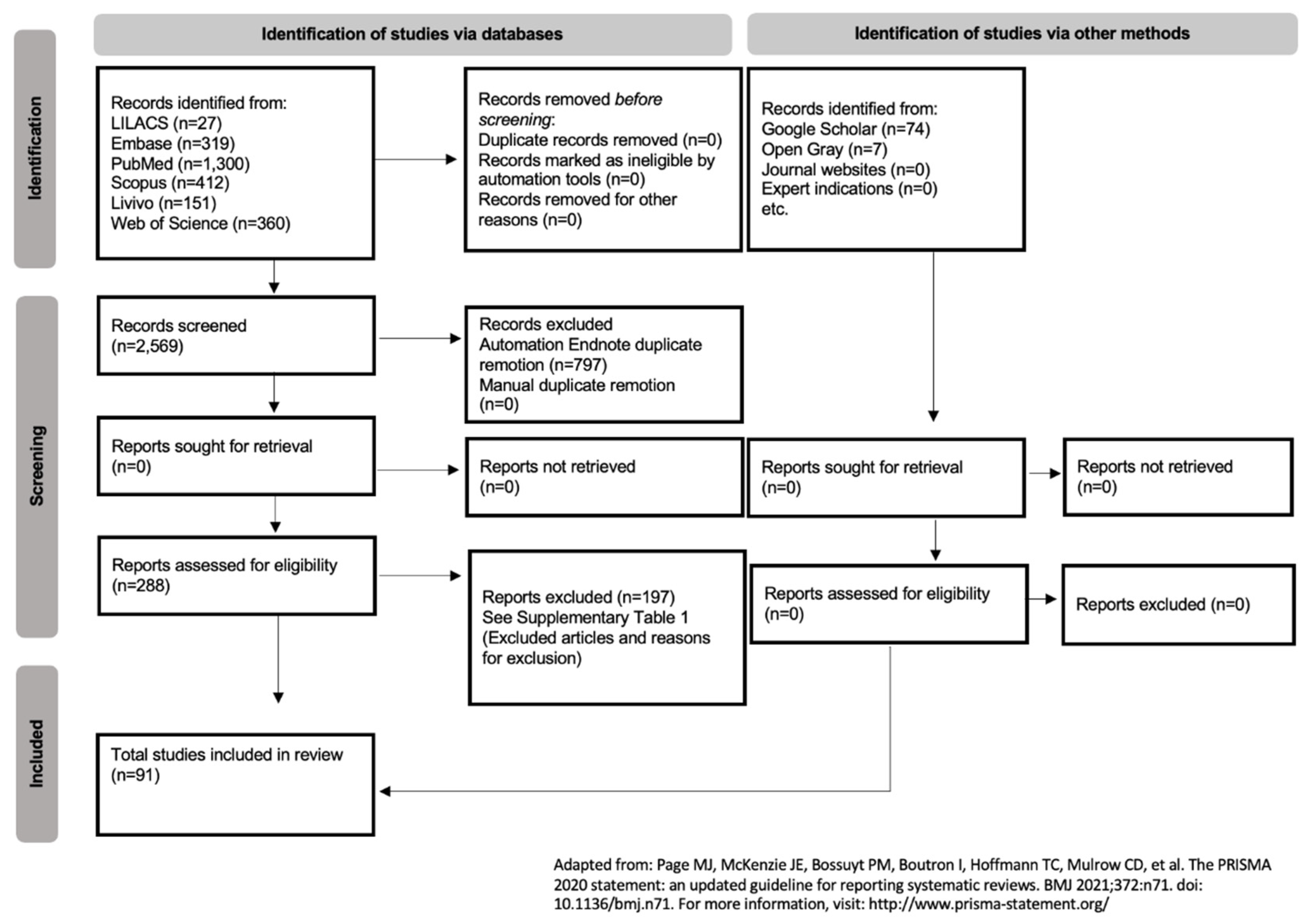

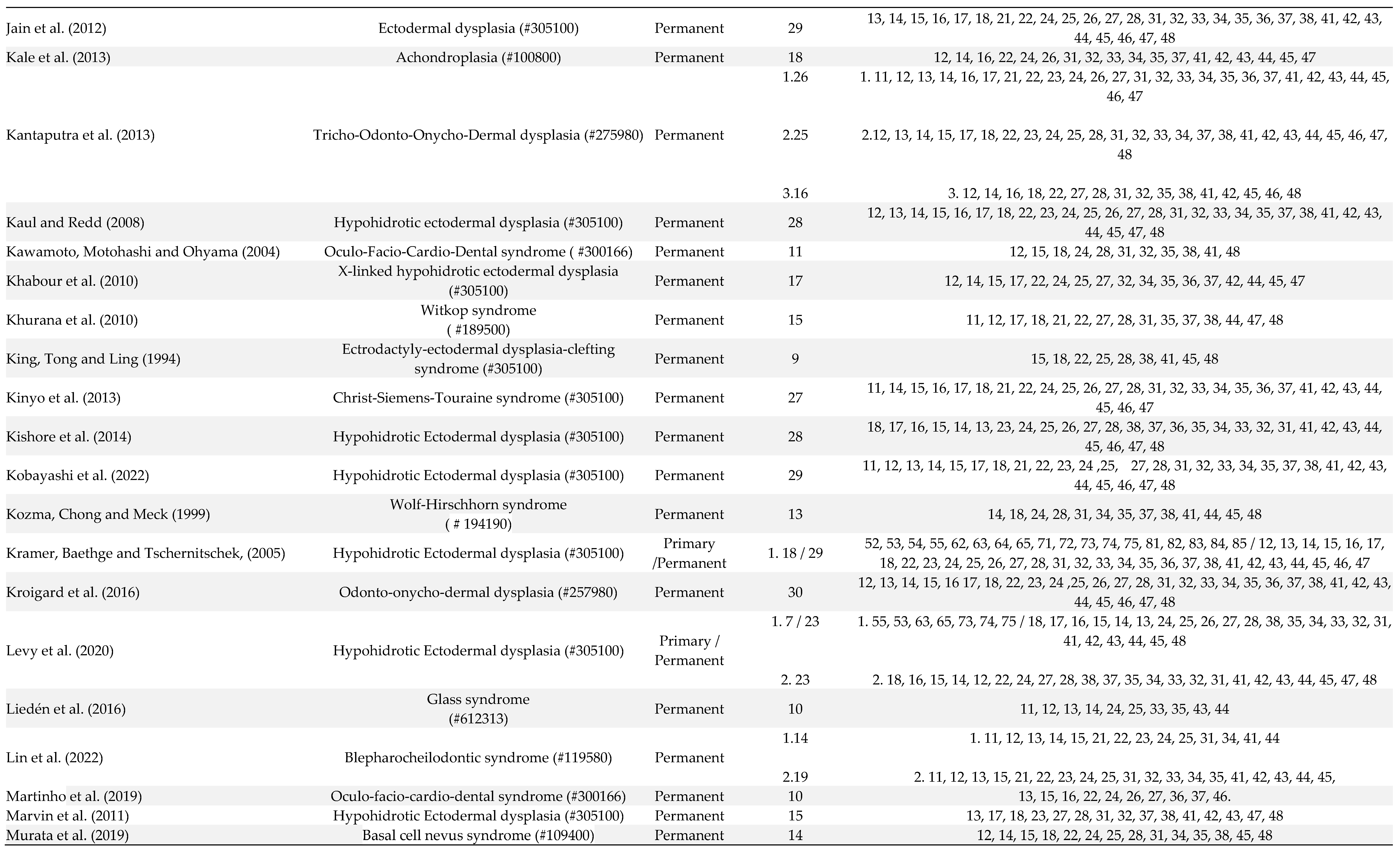

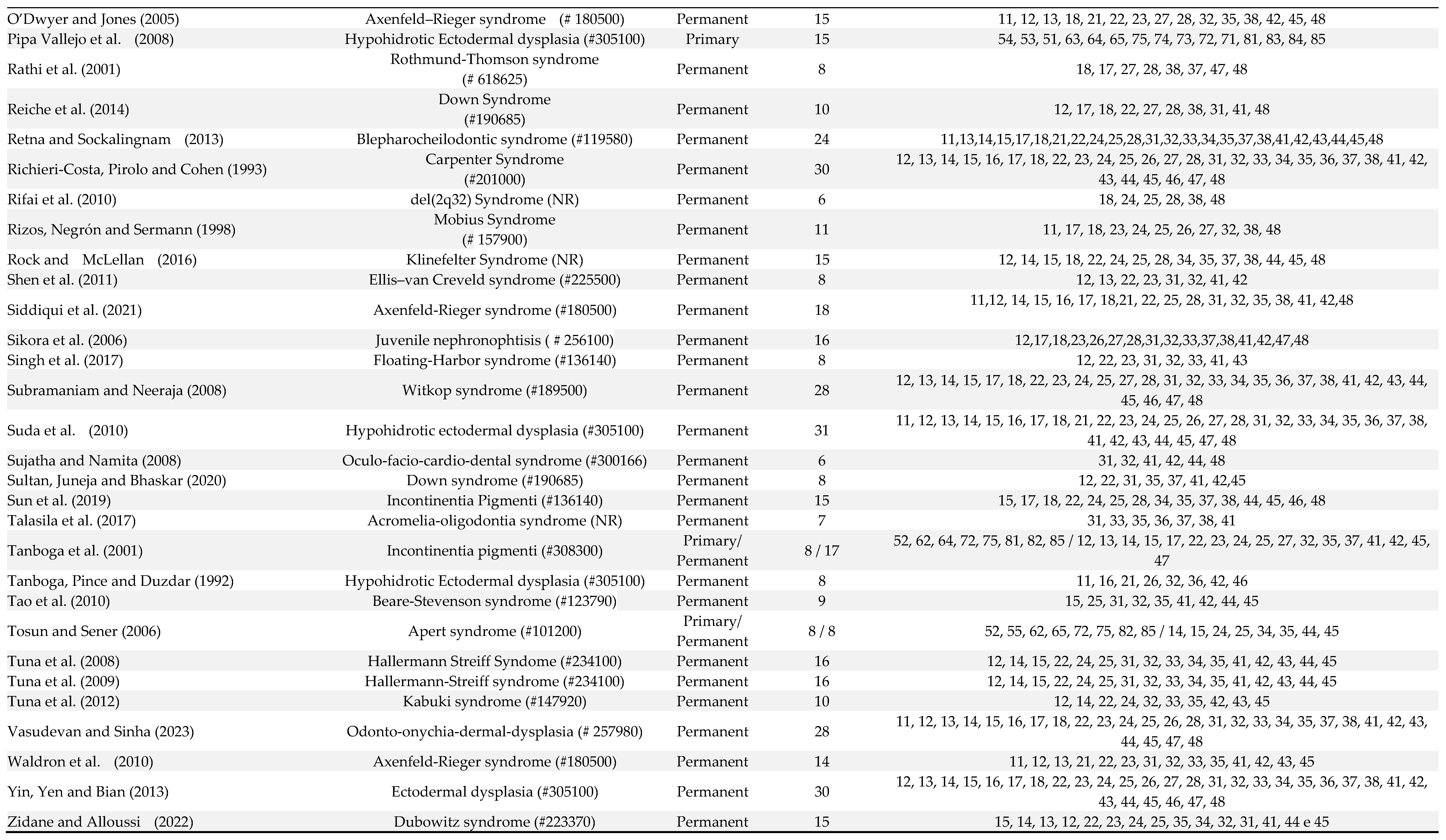

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

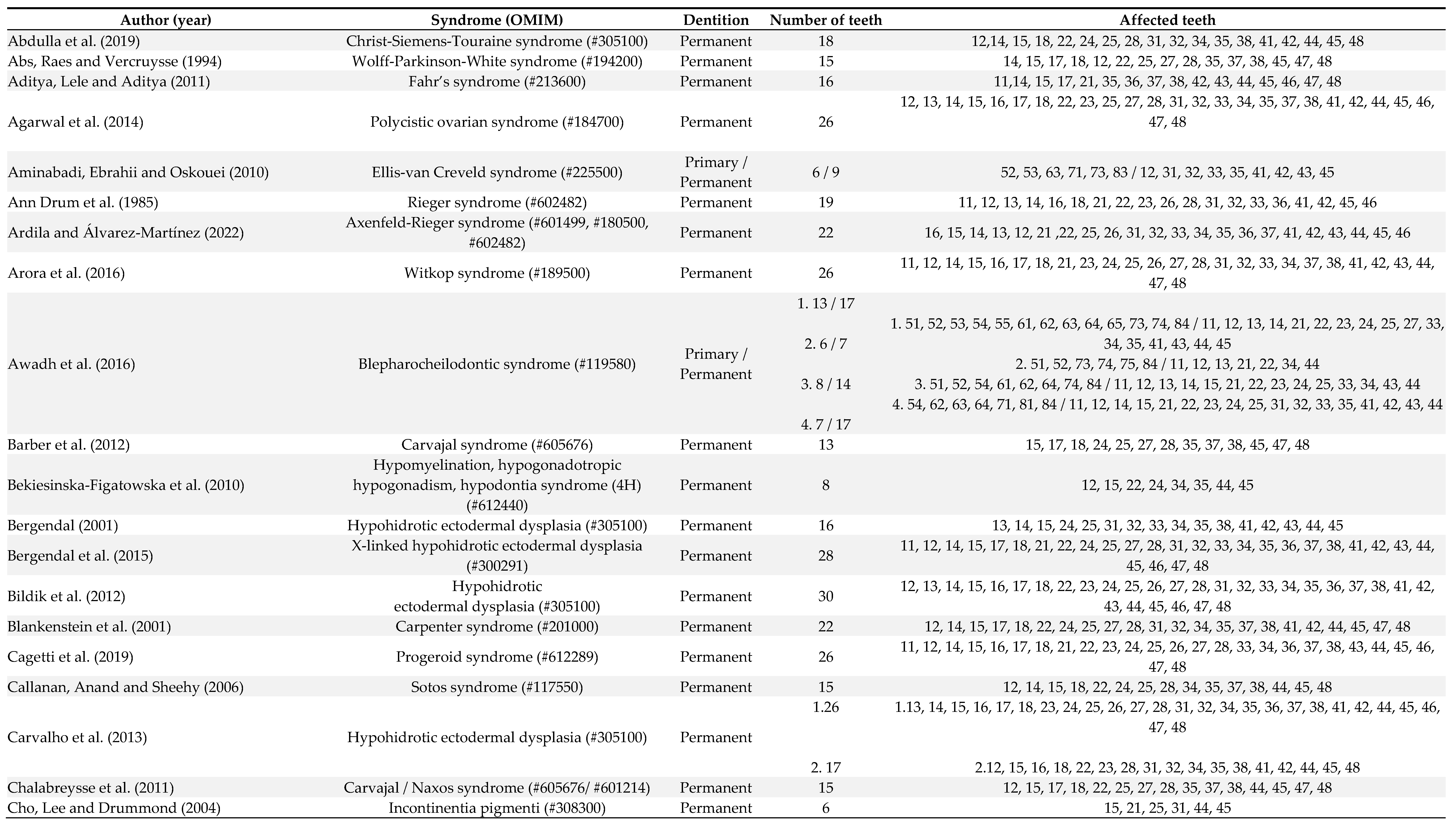

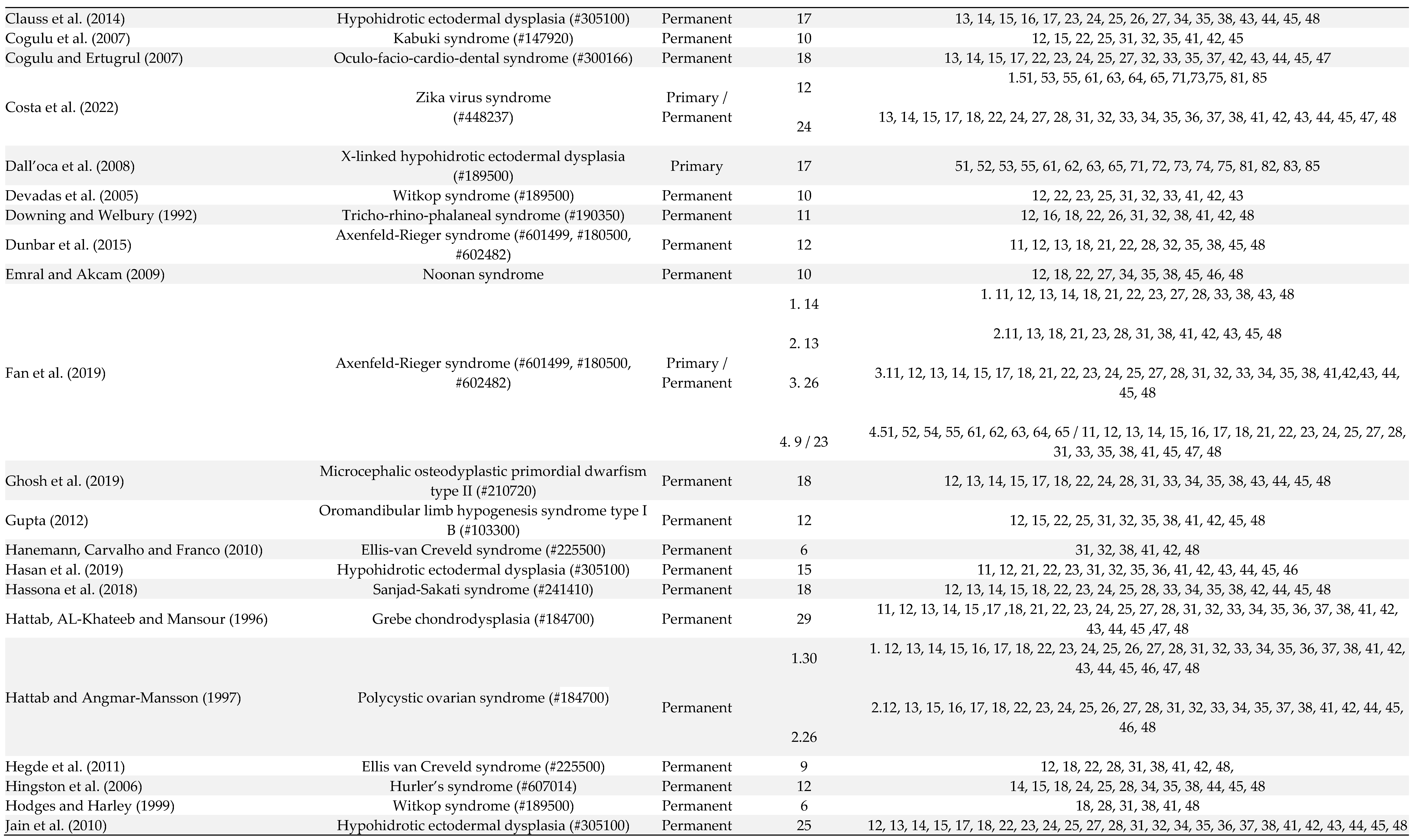

2.4. Data Collection Process and Data Items

2.5. Risk of Bias within Studies

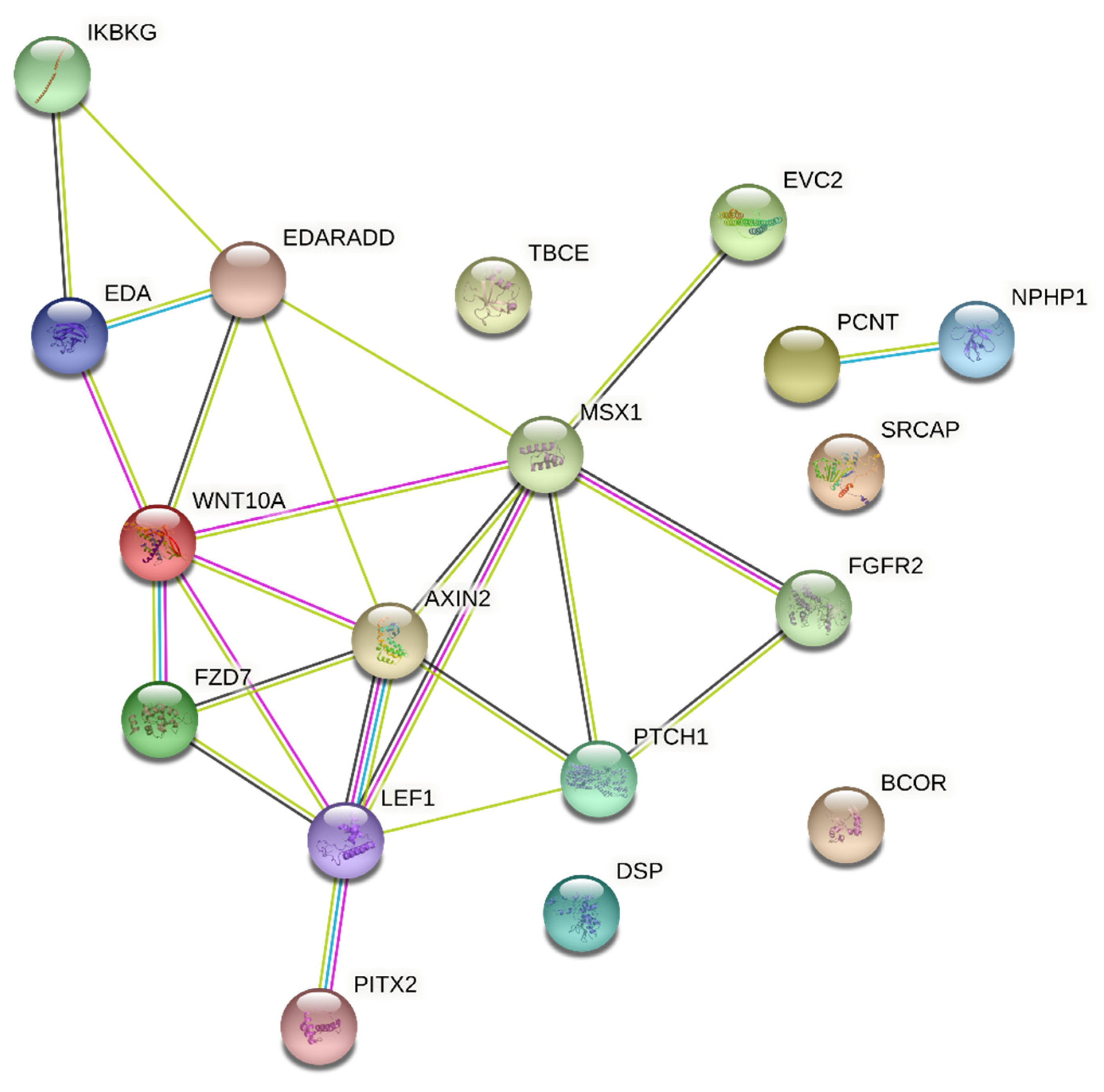

2.6. Interaction Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De La Dure-Molla, M.; Fournier, B.P.; Manzanares, M.C.; Acevedo, A.C.; Hennekam, R.C.; Friedlander, L.; Boy-Lefèvre, M.; Kerner, S.; Toupenay, S.; Garrec, P.; et al. Elements of morphology: Standard terminology for the teeth and classifying genetic dental disorders. Am. J. Med Genet. Part A 2019, 179, 1913–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weide, Y.S.-V.; Beemer, F.; Faber, J.; Bosman, F. Symptomatology of patients with oligodontia. J. Oral Rehabilitation 1994, 21, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Shen, Y.; Zheng, J. [Progress in genetic research on tooth agenesis associated with Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi 2021, 38, 506–509. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Ani, A.H.; Antoun, J.S.; Thomson, W.M.; Merriman, T.R.; Farella, M. Hypodontia: An Update on Its Etiology, Classification, and Clinical Management. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 9378325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brook, H. Multilevel complex interactions between genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors in the aetiology of anomalies of dental development. Archives of Oral Biology 2009, 54, S3–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieminen, P.; Arte, S.; Pirinen, S.; Peltonen, L.; Thesleff, I. Gene defect in hypodontia: exclusion of MSX1 and MSX2 as candidate genes. Hum. Genet. 1995, 96, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorlin RJ. Syndromes of head and neck (2nd ed.), Oxford, USA. 2001.

- Vieira, A. Oral Clefts and Syndromic Forms of Tooth Agenesis as Models for Genetics of Isolated Tooth Agenesis. J. Dent. Res. 2003, 82, 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, R.; Sato, A.; Arai, K. Consecutive tooth agenesis patterns in non-syndromic oligodontia. Odontology 2021, 110, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritwik, P.; Partsson, K.K. Diagnosis of Tooth Agenesis in Childhood and Risk for Neoplasms in Adulthood. The Ochsner Journal 2018, 18, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, J.; Gurunathan, D.; Rangeeth, B.N.; Kannan, K.S. Non-syndromic oligodontia of primary and permanent dentition: 5 years follow up- a rare case report. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research 2013, 7, 776–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.N.; Ruigrok, L.C.; Fennis, W.M.M.; Cuen, M.S.; Rosenberg, A.J.W.P.; van Nunen, A.B.; et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with isolated oligodontia and a Wnt gene mutation. Oral Diseases 2023, 29, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adaimy, L.; Chouery, E.; Mégarbané, H.; Mroueh, S.; Delague, V.; Nicolas, E.; Belguith, H.; de Mazancourt, P.; Mégarbané, A. Mutation in WNT10A Is Associated with an Autosomal Recessive Ectodermal Dysplasia: The Odonto-onycho-dermal Dysplasia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Coster, P.J.; Marks, L.A.; Martens, L.C.; Huysseune, A. Dental agenesis: genetic and clinical perspectives. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2008, 38, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordgarden, H.; Jensen, J.; Storhaug, K. Oligodontia is associated with extra-oral ectodermal symptoms and low whole salivary flow rates. Oral Diseases 2001, 7, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dhamo, B.; Kuijpers, M.A.R.; Balk-Leurs, I.; Boxum, C.; Wolvius, E.B.; Ongkosuwito, E.M. Disturbances of dental development distinguish patients with oligodontia-ectodermal dysplasia from isolated oligodontia. Orthod. Craniofacial Res. 2017, 21, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLOS Med. 2021, 18, e1003583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; et al. Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer’s manual. Adelaide (Australia): Joanna Briggs Institute. Chap 7. 2017.

- Galluccio, G.; Castellano, M.; La Monaca, C. Genetic basis of non-syndromic anomalies of human tooth number. Arch. Oral Biol. 2012, 57, 918–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øgaard, B.; Krogstad, O. Craniofacial structure and soft tissue profile in patients with severe hypodontia. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1995, 108, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, B.; Lu, H.; Xiao, X.; Zhou, L.; Lu, J.; Zhu, L.; et al. Novel EDA mutation in X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia and genotype-phenotype correlation. Oral Diseases 2015, 21, 994–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, E.; Rotenberg, I.S.; Pimpão, C.T. X-Linked Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia—General Features and Dental Abnormalities in Affected Dogs Compared With Human Dental Abnormalities. Top. Companion Anim. Med. 2019, 35, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes-Reali, J.; Mendoza-Ramos, M.I.; Garrido-Guerrero, E.; Méndez-Catalá, C.F.; Méndez-Cruz, A.R.; Pozo-Molina, G. Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia: clinical and molecular review. Int. J. Dermatol. 2018, 57, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lexner, M.; Bardow, A.; Juncker, I.; Jensen, L.; Almer, L.; Kreiborg, S.; Hertz, J. X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Genetic and dental findings in 67 Danish patients from 19 families. Clin. Genet. 2008, 74, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baujat, G.; Le Merrer, M. Ellis-van Creveld syndrome. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2007, 2, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susami, T.; Kuroda, T.; Yoshimasu, H.; Suzuki, R. Ellis-van Creveld syndrome: craniofacial morphology and multidisciplinary treatment. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal 1999, 36, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cogulu, D.; Oncag, O.; Celen, E.; Ozkinay, F. Kabuki Syndrome with additional dental findings: a case report. Journal of Dentistry for Children 2008, 75, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sujatha, R. Barriers in Career Growth of Women Managers: An Indian Scenario. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2008, 4, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, S.; Harley, K. Witkop tooth and nail syndrome: report of two cases in a family. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2001, 9, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifi, M.; Walter, M.A. Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome. Clin Genet. 2018, 93, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.S.; Zabaleta, A.; Kume, T.; Savinova, O.V.; Kidson, S.H.; Martin, J.E.; Nishimura, D.Y.; Alward, W.L.M.; Hogan, B.L.M.; John, S.W.M. Haploinsufficiency of the transcription factors FOXC1 and FOXC2 results in aberrant ocular development. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000, 9, 1021–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, M.T.; Lucci, L.M.; Anderson, R.L. Management of eyelid anomalies associated with Blepharo-cheilo-dontic syndrome. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2001, 132, 279–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuzoff, D.V.; Tuzova, L.N.; Bornstein, M.M.; Krasnov, A.S.; Kharchenko, M.A.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Sveshnikov, M.M.; Bednenko, G.B. Tooth detection and numbering in panoramic radiographs using convolutional neural networks. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2019, 48, 20180051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Román, J.C.M.; Fretes, V.R.; Adorno, C.G.; Silva, R.G.; Noguera, J.L.V.; Legal-Ayala, H.; Mello-Román, J.D.; Torres, R.D.E.; Facon, J. Panoramic Dental Radiography Image Enhancement Using Multiscale Mathematical Morphology. Sensors 2021, 21, 3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.C.; Line, S.R. The genetics of amelogenesis imperfecta: a review of the literature. Journal of applied oral science 2005, 13, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vastardis, H. The genetics of human tooth agenesis: new discoveries for understanding dental anomalies. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2000, 117, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalabreysse, L.; Senni, F.; Bruyère, P.; Aime, B.; Ollagnier, C.; Bozio, A.; et al. A new hypo/oligodontia syndrome: Carvajal/Naxos syndrome secondary to desmoplakin-dominant mutations. Journal of Dental Research 2011, 90, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauss, F.; Waltmann, E.; Barriere, P.; Hadj-Rabia, S.; Manière, M.-C.; Schmittbuhl, M. Dento-maxillo-facial phenotype and implants-based oral rehabilitation in Ectodermal Dysplasia with WNT10A gene mutation: Report of a case and literature review. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2014, 42, e346–e351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Sun, S.; Liu, H.; Yu, M.; Liu, Z.; Wong, S.W.; et al. Novel PITX2 mutations identified in Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome and the pattern of PITX2-related tooth agenesis. Oral Diseases 2019, 25, 2010–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Garg, M.; Gupta, S.; Choudhary, M.; Chandra, M. Microcephalic osteodyplastic primordial dwarfism type II: case report with unique oral findings and a new mutation in the pericentrin gene. Oral Surgery, Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2019, 129, e204–e211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantaputra, P.; Kaewgahya, M.; Hatsadaloi, A.; Vogel, P.; Kawasaki, K.; Ohazama, A.; Cairns, J.K. GREMLIN 2 Mutations and Dental Anomalies. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 1646–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabour, O.; Mesmar, F.; Al-Tamimi, F.; Al-Batayneh, O.; Owais, A. Missense mutation of the EDA gene in a Jordanian family with X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia: phenotypic appearance and speech problems. Genet. Mol. Res. 2010, 9, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khurana, V.K.; Gupta, R.K.; Kumar, L.P. Witkop syndrome: A case report of an affected family. Dermatol. Online J. 2012, 18, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinyó, A.; Vályi, P.; Farkas, K.; Nagy, N.; Gergely, B.; Tripolszki, K.; Török, D.; Bata-Csörgő, Z.; Kemény, L.; Széll, M. A newly identified missense mutation of the EDA1 gene in a Hungarian patient with Christ–Siemens–Touraine syndrome. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2013, 306, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krøigård, A.B.; Thomassen, M.; Lænkholm, A.-V.; Kruse, T.A.; Larsen, M.J. Evaluation of Nine Somatic Variant Callers for Detection of Somatic Mutations in Exome and Targeted Deep Sequencing Data. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0151664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvin, M.L.; Mazzoni, S.M.; Herron, C.M.; Edwards, S.; Gruber, S.B.; Petty, E.M. AXIN2-associated autosomal dominant ectodermal dysplasia and neoplastic syndrome. Am. J. Med Genet. Part A 2011, 155, 898–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murata, Y.; Kurosaka, H.; Ohata, Y.; Aikawa, T.; Takahata, S.; Fujii, K.; Miyashita, T.; Morita, C.; Inubushi, T.; Kubota, T.; et al. A novel PTCH1 mutation in basal cell nevus syndrome with rare craniofacial features. Hum. Genome Var. 2019, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Han, D.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, H.; Feng, H. Two novel heterozygous mutations of EVC2 cause a mild phenotype of Ellis-van Creveld syndrome in a Chinese family. Am. J. Med Genet. Part A 2011, 155, 2131–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Ye, X.; Bian, Z. The Second Deletion Mutation in Exon 8 of EDA Gene in an XLHED Pedigree. Dermatology 2013, 226, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantaputra, P.N.; Bongkochwilawan, C.; Kaewgahya, M.; Ohazama, A.; Kayserili, H.; Erdem, A.P.; et al. Enamel-Renal-Gingival syndrome, hypodontia, and a novel FAM20A mutation. American journal of medical genetics Part A 2014, 164A, 2124–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, B.; Zhao, Q.; Li, S.; Lu, H.; Lu, J.; Ma, L.; Zhao, W.; Yu, D. Novel EDA or EDAR Mutations Identified in Patients with X-Linked Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia or Non-Syndromic Tooth Agenesis. Genes 2017, 8, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, F.; Sgattoni, C.; Bencardino, D.; Simonetti, O.; Forabosco, A.; Magnani, M. Missense mutations in EDA and EDAR genes cause dominant syndromic tooth agenesis. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2020, 9, e1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mues, G.; Tardivel, A.; Willen, L.; Kapadia, H.; Seaman, R.; Frazier-Bowers, S.; Schneider, P.; D'Souza, R.N. Functional analysis of Ectodysplasin-A mutations causing selective tooth agenesis. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2009, 18, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peck, J.; Douglas, G.; Wu, C.H.; Burbelo, P.D. Human RhoGAP domain-containing proteins: structure, function and evolutionary relationships. FEBS Lett. 2002, 528, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieminen, P. Genetic basis of Tooth agenesis. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution 2009, 312, 320–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Der Weide, Y.S.-V.; Steen, W.H.; Bosman, F. Distribution of missing teeth and tooth morphology in patients with oligodontia. ASDC J. Dent. Child. 1992, 59, 133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Weide, Y.S.; Prahl-Andersen, B.; Bosman, F. Tooth formation in patients with oligodontia. Angle Orthod. 1993, 63, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polder, B.J.; Hof, M.A.V.; Van der Linden, F.P.G.M.; Kuijpers-Jagtman, A.M. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of dental agenesis of permanent teeth. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiology 2004, 32, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).