Submitted:

03 September 2023

Posted:

05 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

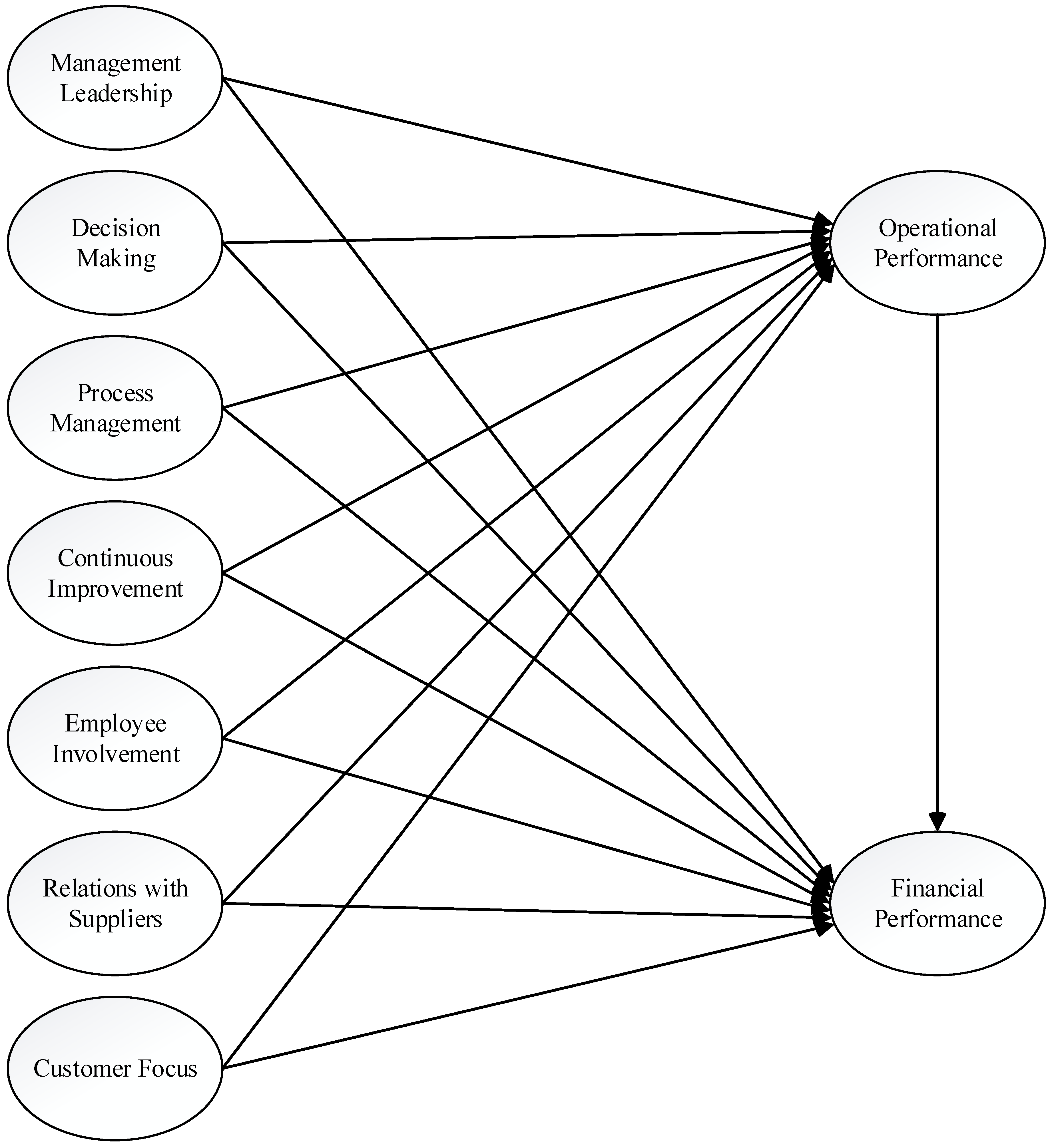

Literature review and hypotheses development

Management leadership

Decision making

Process management

Continuous improvement

Employee involvement

Relations with suppliers

Customer focus

Operational performance

Financial performance

3. Results

Research methodology

The nature of the research

Measurement instrument for TQM practices

Sample demographics

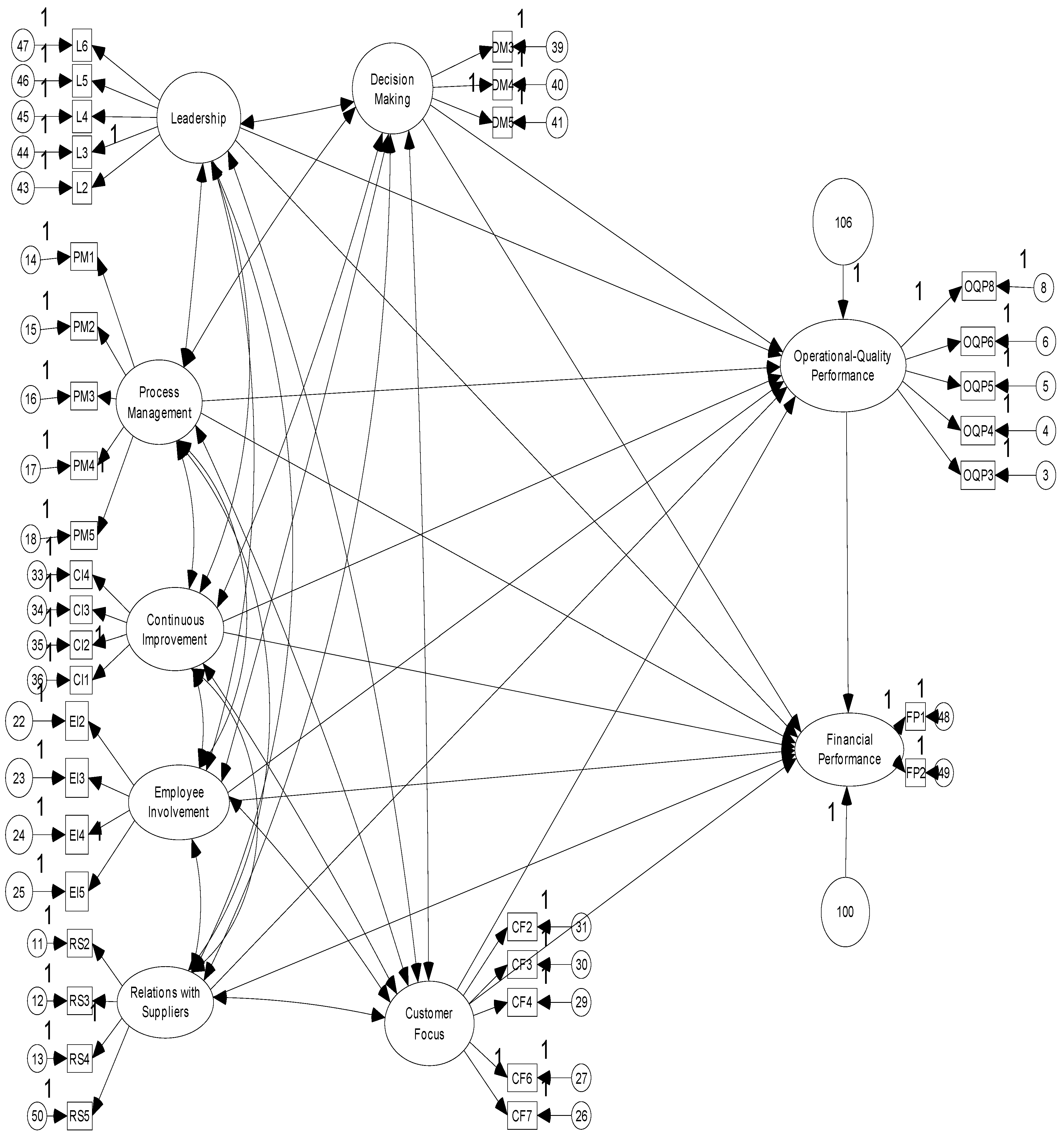

Statistical analysis

| Factor name | Reason for Elimination | CMIN/df | GFI | AGFI | NFI | IFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CF5 | Eliminated in EFA | 3,937 | ,848 | ,829 | ,888 | ,914 | ,907 | ,914 | ,052 |

| PM6 | SR | 3,800 | ,859 | ,841 | ,894 | ,920 | ,913 | ,914 | ,051 |

| PM7 | SR | 3,743 | ,863 | ,845 | ,898 | ,923 | ,916 | ,923 | ,051 |

| RS1 | SR | 3,738 | ,865 | ,847 | ,900 | ,925 | ,918 | ,925 | ,051 |

| OQP1 | MI; SR | 3,503 | ,877 | ,861 | ,908 | ,932 | ,926 | ,932 | ,048 |

| OQP7 | MI; SR | 3,374 | ,884 | ,867 | ,912 | ,936 | ,930 | ,936 | ,047 |

| EI1 | MI; SR | 3,298 | ,889 | ,873 | ,915 | ,939 | ,933 | ,939 | ,046 |

| DM1 | MI; SR | 3,230 | ,895 | ,879 | ,919 | ,943 | ,937 | ,943 | ,046 |

| OQP2 | MI; SR | 3,072 | ,902 | ,886 | ,924 | ,948 | ,942 | ,948 | ,044 |

| L1 | MI; SR | 2,979 | ,907 | ,891 | ,929 | ,952 | ,946 | ,951 | ,043 |

| DM2 | MI | 2,975 | ,910 | ,894 | ,931 | ,953 | ,948 | ,953 | ,043 |

| OQP9 | SR | 2,950 | ,913 | ,897 | ,934 | ,955 | ,950 | ,955 | ,043 |

| CF 1 | MI; SR | 2,886 | ,918 | ,937 | ,957 | ,958 | ,952 | ,958 | ,042 |

4. Discussion

| Hypothesized link | Estimate | Standardized Estimate | SE | CR | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leadership | → | Operational-Quality Performance |

,151 | ,134 | ,058 | 2,601 | ,009*** |

| Decision Making | → | Operational-Quality Performance |

,111 | ,095 | ,063 | 1,755 | ,079* |

| Continuous Improvement | → | Operational-Quality Performance |

,076 | ,077 | ,045 | 1,711 | ,087* |

| Customer Focus | → | Operational-Quality Performance |

,387 | ,357 | ,044 | 8,792 | ,000*** |

| Employee Involvement | → | Operational-Quality Performance |

,021 | ,026 | ,033 | ,639 | ,523 |

| Process Management | → | Operational-Quality Performance |

,006 | ,006 | ,044 | ,136 | ,892 |

| Relations with Suppliers | → | Operational-Quality Performance |

,163 | ,201 | ,031 | 5,214 | ,000*** |

| Leadership | → | Financial Performance | ,108 | ,078 | ,079 | 1,357 | ,175 |

| Decision Making | → | Financial Performance | -,008 | -,005 | ,087 | -,090 | ,929 |

| Continuous Improvement | → | Financial Performance | ,035 | ,029 | ,061 | ,580 | ,562 |

| Customer Focus | → | Financial Performance | ,285 | ,213 | ,063 | 4,513 | ,000*** |

| Employee Involvement | → | Financial Performance | ,025 | ,025 | ,045 | ,556 | ,578 |

| Process Management | → | Financial Performance | ,102 | ,080 | ,061 | 1,669 | ,095* |

| Relations with Suppliers | → | Financial Performance | ,028 | ,028 | ,043 | ,657 | ,511 |

| Operational-Quality Performance | → | Financial Performance | ,330 | ,266 | ,058 | 5,728 | ,000*** |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Measurement scales, survey items, and their sources

A.1. Leadership of management

A.2. Decision Making

A.3. Continuous Improvement

A.4. Customer focus

A.5. Employee Involvement

A.6. Process Management

A.7. Relations with suppliers

A.8. Operational and quality performance

A.9. Financial performance

References

- Ali, K.; Johl, S. K.; Muneer, A.; Alwadain, A.; Ali, R. F. Soft and Hard Total Quality Management Practices Promote Industry 4.0 Readiness: A SEM-Neural Network Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14 (19), 11917. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911917. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. A. Evolution of the Health Care Quality Journey. Journal of Legal Medicine 2010, 31 (1), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/01947641003598252. [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V. A.; Berry, L. L. A Conceptual Model of Service Quality and Its Implications for Future Research. Journal of Marketing 1985, 49 (4), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298504900403. [CrossRef]

- Zabada, C.; Rivers, A. P.; Munchus, G. Obstacles to the Application of Total Quality Management in Health Care Organizations. Total Quality Management 1998, 9, 57–66. [CrossRef]

- Tomes, A. E.; Chee Peng Ng, S. Service Quality in Hospital Care: The Development of an in-Patient Questionnaire. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 1995, 8 (3), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/09526869510089255. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, W. E. W.; Jusoff, H. K. Service Quality in Health Care Setting. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 2009, 22 (5), 471–482. https://doi.org/10.1108/09526860910975580. [CrossRef]

- Mosadeghrad, A. Developing and Validating a Total Quality Management Model for Healthcare Organizations. The TQM Journal 2015, 27 (5), 544–564. [CrossRef]

- Swinehart, K.; Green, R. F. Continuous Improvement and TQM in Health Care: An Emerging Operational Paradigm Becomes a Strategic Imperative. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 1995, 8 (1), 23–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/09526869510078031. [CrossRef]

- Kessler, D.; Geppert, J. The Effects of Competition on Variation in the Quality and Cost of Medical Care; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, 2005.

- Cooper, Z.; Gibbons, S.; Jones, S.; McGuire, A. Does Hospital Competition Save Lives? Evidence from the English NHS Patient Choice Reforms. London School of Economics Working Paper 2010, 16/2010, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2011.02449.x. [CrossRef]

- Wardhani, V.; Utarini, A.; Van Dijk, J.; Post, D.; Groothoff, J. Determinants of Quality Management Systems Implementation in Hospitals. Health Policy 2009, 89, 239–251. [CrossRef]

- Lim, P. C.; Tang, N. The Development of a Model for Total Quality Healthcare. Managing Service Quality 2000, 10, 103–111. [CrossRef]

- Rodger, J. A.; Pendharkar, P. C.; Paper, D. J. Management of Information Technology and Quality Perfor-Mance in Healthcare Facilities. Int. J of Applied Quality Management 1999, 2, 251–269.

- Nilsson, L.; Johnson, M. D.; Gustafsson, A. The Impact of Quality Practices on Customer Satis-Faction and Business Results: Product versus Service Organizations. J of Quality Management 2001, 6, 5–27. [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. A.; Berry, L. L.; Parasuraman, A. The Behavioral Consequences of Service Quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60 (2), 31. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251929. [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. A Service Quality Model and Its Marketing Implications. Eur. J. Mark. 1984, 18 (4), 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1108/eum0000000004784. [CrossRef]

- Andaleeb, S. S. Public and Private Hospitals in Bangladesh: Service Quality and Predictors of Hospital Choice. Health Policy Plan. 2000, 15 (1), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/15.1.95. [CrossRef]

- Donabedian, A. The Quality of Care: How Can It Be Assessed? J. of the American Medical Association 1988, 260, 1743–1748. [CrossRef]

- Douglas, T. J.; Judge, W. Q. Total Quality Management Implementation and Competitive Advantage: The Role of Structural Control and Exploration. Acad. Manage. J. 2001, 44 (1), 158–169. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069343. [CrossRef]

- Sureshchander, G.; Rajendran, C.; Anantharaman, R. A Conceptual Model for Total Quality Management in Service Organizations. Total Quality Management 2001, 12 (3), 343–363. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-C. The Establishment of a TQM System for the Health Care Industry. TQM Mag. 2003, 15 (2), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1108/09544780310461107. [CrossRef]

- Claver, E.; Tarí, J. J.; Molina, J. F. Critical Factors and Results of Quality Management: An Empirical Study. Total Qual. Manage. Bus. Excel. 2003, 14 (1), 155–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/1478336032000044852. [CrossRef]

- Sila, I.; Ebrahimpour, M. Examination and Comparison of the Critical Factors of Total Quality Management (TQM) across Countries. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2003, 41 (2), 235–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020754021000022212. [CrossRef]

- Conca, F. J.; Llopis, J.; Tarı́, J. J. Development of a Measure to Assess Quality Management in Certified Firms. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2004, 156 (3), 683–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0377-2217(03)00145-0. [CrossRef]

- Deming, W. Quality, Productivity and Competitive Position. Cambridge, M.A.: MIT Center for Advanced Engineering; 1982.

- Juran, J. On Planning for Quality. London: Collier Macmillian.1988.

- Puffer, S. M.; McCarthy, D. J. A Framework for Leadership in a TQM Context. J. Qual. Manag. 1996, 1 (1), 109–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1084-8568(96)90008-5. [CrossRef]

- Koumoutzis, N. Make Behavioral Considerations Your First Priority in Quality Improvements. Industrial Engineering 1994, 26, 63–65.

- Tarí, J. J.; Molina, J. F.; Castejón, J. L. The Relationship between Quality Management Practices and Their Effects on Quality Outcomes. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 183 (2), 483–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2006.10.016. [CrossRef]

- Daft, R. New Era of Management. South Western: Cengage Learning. 2008.

- Lee, S.; Choi, K.-S.; Kang, H.-Y.; Cho, W.; Chae, Y. M. Assessing the Factors Influencing Continuous Quality Improvement Implementation: Experience in Korean Hospitals. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2002, 14 (5), 383–391. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/14.5.383. [CrossRef]

- Zehir, C.; Ozsahin, M. A Field Research on the Relationship Between Strategic Decision Making Speed and Innovation Performance in the Case of Turkish Large Scale Firms. Management Decision 2008, 46, 709–724. [CrossRef]

- Ittner, C. D.; Larcker, D. F. The Performance Effects of Process Management Techniques. Manage. Sci. 1997, 43 (4), 522–534. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.43.4.522. [CrossRef]

- Reed, R.; Lemak, D. J.; Montgomery, J. C. Beyond Process: TQM Content and Firm Performance. Acad. Manage. Rev. 1996, 21 (1), 173–202. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1996.9602161569. [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Dahlgaard, S. M. Organizational Learnability and Innovability”,A System for Assessing, Diagnosing and Improving Innovations. Academy of Management Review 1994, 19, 392–418.

- Bowen, D. E. Managing Customers as Human Resources in Service Organizations. Hum. Resour. Manage. 1986, 25 (3), 371–383. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.3930250304. [CrossRef]

- Shortell, S. M.; Obrien, J. L.; Carman, J. M.; Foster, R. W.; Hughes, E.; Boerstler, H.; Connor, O. Assessing the Impact of Continuous Quality Improvement / Total Quality Management: Concept versus Implementation. Health Serv Res 1995, 30, 377–401.

- Rad, A. A Survey of Total Quality Management in Iran: Barriers to Successful Implementation in Hospitals. Leadership in Health Services 2005, 18, 12–34. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, H. C. Teamwork Brings TQM to Health Care. Managing Service Quality. 1994, 4, 35–38. [CrossRef]

- Matej, Z.; Matjaz, M.; Damjan, M.; Bostjan, G. Quality Management Systems as a Link between Management and Employees. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 2012, 23 (1), 45–62. [CrossRef]

- Welikala, D.; Sohal, A. Total Quality Management and Employees’ Involvement: A Case Study of an Australian Organisation. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 2008, 19 (6), 627–642. [CrossRef]

- Agus, A. An Empirical Test of TQM in Public Service Sector and Its Impact on Customer Satisfaction. Journal of Quality Measurement and Analysis 2005, 1 (1), 47–60.

- Ahmad, S.; Schroeder, R. G. The Importance of Recruitment and Selection Process for Sustainability of Total Quality Management. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2002, 19 (5), 540–550. https://doi.org/10.1108/02656710210427511. [CrossRef]

- Flynn, B. B.; Schroeder, R. G.; Sakakibara, S. The Impact of Quality Management Practices on Performance and Competitive Advantage. Decis. Sci. 1995, 26 (5), 659–691. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.1995.tb01445.x. [CrossRef]

- Forza, C.; Filippini, R. TQM Impact on Quality Conformance and Customer Satisfaction: A Causal Model. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 1998, 55 (1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0925-5273(98)00007-3. [CrossRef]

- Trent, R. J.; Monczka, R. M. Achieving World-Class Supplier Quality. Total Qual. Manag. 1999, 10 (6), 927–938. https://doi.org/10.1080/0954412997334. [CrossRef]

- Kannan, V. R.; Tan, K. C. Just in Time, Total Quality Management, and Supply Chain Management: Understanding Their Linkages and Impact on Business Performance. Omega 2005, 33, 153–162. [CrossRef]

- Krause, D. R.; Handfield, R. B.; Scannell, T. V. An Empirical Investigation of Supplier Development: Reactive and Strategic Processes. J. Oper. Manage. 1998, 17 (1), 39–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-6963(98)00030-8. [CrossRef]

- Kaynak, H. The Relationship between Total Quality Management Practices and Their Effects on Firm Performance. J. Oper. Manage. 2003, 21 (4), 405–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-6963(03)00004-4. [CrossRef]

- Zineldin, M. The Royalty of Loyalty: CRM, Quality and Retention. J. Consum. Mark. 2006, 23 (7), 430–437. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760610712975. [CrossRef]

- Samson, D.; Terziovski, M. The Relationship between Total Quality Management Practices and Operational Peformance. J of Operations Management 1999, 17, 393–409. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-I.; Chan, H.-J. Perceived Service Quality and Self-Concept Influences on Consumer Attitude and Purchase Process: A Comparison between Physical and Internet Channels. Total Qual. Manage. Bus. Excel. 2011, 22 (1), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2010.529645. [CrossRef]

- Sajid, M. S.; Baig, M. K. Quality of Health Care: An Absolute Necessity for Public Satisfaction. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 2007, 20 (6), 545–548. https://doi.org/10.1108/09526860710819477. [CrossRef]

- Parkan, C.; Wu, M. L. On the Equivalence of Operational Performance Measurement and Multiple Attribute Decision Making. Int. J. Prod. Res. 1997, 35 (11), 2963–2988. https://doi.org/10.1080/002075497194246. [CrossRef]

- Ho, S. K. M. Total Quality Management Transfer to Small and Medium Industries in Malaysia by SIRIM. Total Qual. Manag. 1995, 6 (3), 273–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/09544129550035440. [CrossRef]

- Hubiak, W. A.; Odonnell, S. J. Do Americans Have Their Minds Set against TQM?(Abstract). National Productivity Review 1996, 15, 19–32. [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J. J., Jr; Taylor, S. A. Servperf versus Servqual: Reconciling Performance-Based and Perceptions-Minus-Expectations Measurement of Service Quality. J. Mark. 1994, 58 (1), 125–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299405800110. [CrossRef]

- Singh, J. Consumer Complaint Intentions and Behavior: Definitional and Taxonomical Issues. J. Mark. 1988, 52 (1), 93. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251688. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J. A.; Weiner, B. J.; Griffith, J. Quality Improvement and Hospital Financial Performance. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27 (7), 1003–1029. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.401. [CrossRef]

- Rust, R. T.; Zahorik, A. J.; Keiningham, T. L. Return on Quality: Making Service Quality Financially Accountable. The J of Marketing 1995, 59, 58–70. [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. A. Service Quality, Profitability and the Economic Worth of Customers: What We Know and What We Need to Learn. Journal of Academy of Marketing Science 2000, 28, 67–85. [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G. A., Jr. A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16 (1), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377901600110. [CrossRef]

- Cua, K. O.; McKone, K. E.; Schroeder, R. G. Relationships between Implementation of TQM, JIT, and TPM and Manufacturing Performance. J. Oper. Manage. 2001, 19 (6), 675–694. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-6963(01)00066-3. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Fuentes, M. M.; Ca, A.-S. Llorens-Montes FJ. The Impact of Environmental Characteristics on TQM Principles and Organizational Performance. Omega 2004, 32, 425–442. [CrossRef]

- Saraph, J. V.; Benson, P. G.; Schroeder, R. G. An Instrument for Measuring the Critical Factors of Quality Management. Decis. Sci. 1989, 20 (4), 810–829. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.1989.tb01421.x. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Bullock, P. Soft TQM, Hard TQM and Organizational Performance Relationships: An Empirical Investigation. Omega 2005, 33, 73–83. [CrossRef]

- Chong, V. K.; Rundus, M. J. Total Quality Management, Market Competition and Organizational Performance. The British Accounting Review 2004, 36, 155–172. [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.; Philips, L. Representing and Testing Organizational Theories: A Holistic Construct. Administrative Science Quarterly 1982, 27, 459–489. [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, B.; Muthen, B.; Alwin, D. F.; Summers, G. F. Assessing Reliability and Stability in Panel Models. Sociol. Methodol. 1977, 8, 84. https://doi.org/10.2307/270754. [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.; Hocevar, D. Application of Confirmatory Factor Analysis to the Study of Self-Concept: First and Higher Order Factor Structures and Their Invariance Across Groups. Psychological Bulletin 1995, 97, 562–582.

- Carmines, E.; Mciver, J. Analyzing Models with Unobserved Variables: Analysis of Covariance Structures. G. Bohrnstedt, & E. Borgatta, In Social Measurement: Current Issues 1981, 65–115.

- Chau, P. Y. K. Reexamining a Model for Evaluating Information Center Success Using a Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Decis. Sci. 1997, 28 (2), 309–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.1997.tb01313.x. [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P. M.; Kano, Y. On the Equivalence of Factors and Components. Multivariate Behav. Res. 1990, 25 (1), 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr2501_8. [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.; Bonett, D. Significant Test Goodness of Fit in the Analysis of Covariance Structures. Psychological Bulletin 1980, 88, 588–606. [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, J. L. AMOS 16.0. SpringHouse, PA: Amos Development Corporation. 2007.

- Fornell, D.; Larcker, D. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research 1981, 18 (1), 39–50. [CrossRef]

- Nunnaly, J. Psychometric Theory (2 b.). New York: McGraw Hill. 1978.

- Grandzol, J. R.; Gershon, M. Which TQM Practices Really Matter: An Empirical Investigation. Qual. Manag. J. 1997, 4 (4), 43–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/10686967.1998.11919147. [CrossRef]

- Ahire, S. L.; O’Shaughnessy, K. C. The Role of Top Management Commitment in Quality Management: An Empirical Analysis of the Auto Parts Industry. Int. J. Qual. Sci. 1998, 3 (1), 5–37. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598539810196868. [CrossRef]

- Nair, A. Meta-Analysis of the Relationship between Quality Management Practices and Firm Performance Implications for Quality Management Theory Development. J of Operations Management 2006, 24, 948–975. [CrossRef]

- Dagger, T. C.; Sweeney, J. C.; Johnson, L. W. A Hierarchical Model of Health Service Quality: Scale Development and Investigation of Integrated Model. J of Serv Res 2007, 10, 123–142. [CrossRef]

- Tanninen, K.; Puumalainen, K.; Sandström, J. The Power of TQM: Analysis of Its Effects on Profitability, Productivity and Customer Satisfaction. Total Qual. Manage. Bus. Excel. 2010, 21 (2), 171–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783360903549949. [CrossRef]

- Andaleeb, S. S.; Siddiqui, N.; Khandakar, S. Patient Satisfaction with Health Services in Bangladesh. Health Policy Plan. 2007, 22 (4), 263–273. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czm017. [CrossRef]

- Naidu, A. Factors Affecting Patient Satisfaction and Healthcare Quality. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 2009, 22 (4), 366–381. https://doi.org/10.1108/09526860910964834. [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Wieseke, J.; Hoyer, W. D. Social Identity and Service Profit Chain. J. of Marketing 2009, 73, 38–54. [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulos, C.; Psomas, E. & Vouzas, F, Investigating Total Quality Management Practice’s in-Ter-Relationships in ISO 9001:2000 Certified Organisations. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 2010, 21 (5), 503–515. [CrossRef]

- Sadikoglu, E.; Zehir, C. Investigating the Effects of Innovation and Employee Performance on the Relationship between Total Quality Management Practices and Firm Performance: An Empirical Study of Turkish Firms. Int J of Production Economics 2010, 127, 13–26. [CrossRef]

- Newman, K.; Maylor, U.; Chansarkar, B. The Nurse Retention, Quality of Care and Patient Satisfaction Chain. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. Inc. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2001, 14 (2–3), 57–68. https://doi.org/10.1108/09526860110386500. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M. T.; Fiss, P. C. Institutionalization, Framing, and Diffusion: The Logic of TQM Adoption and Implementation Decisions among U.s. Hospitals. Acad. Manage. J. 2009, 52 (5), 897–918. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.44633062. [CrossRef]

- Niyi Anifowose, O.; Ghasemi, M.; Olaleye, B. R. Total Quality Management and Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises’ (SMEs) Performance: Mediating Role of Innovation Speed. Sustainability 2022, 14 (14), 8719. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148719. [CrossRef]

- Macinati, M. S. The Relationship between Quality Management Systems and Organizational Performance in the Italian National Health Service. Health Policy 2008, 85 (2), 228–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.07.013. [CrossRef]

| Std.Regression Weights | S.E. | C.R. | p | Cronbach’sAlpha | Composite reliabity | A.V.E | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leadership | .873 | .875 | .585 | |||||

| L2 | .679 | |||||||

| L3 | .778 | .057 | 22.685 | *** | ||||

| L4 | .838 | .056 | 24.137 | *** | ||||

| L5 | .834 | .051 | 24.047 | *** | ||||

| L6 | .682 | .051 | 20.184 | *** | ||||

| Decision Making | .807 | .810 | .586 | |||||

| DM3 | .804 | .052 | 23.040 | *** | ||||

| DM4 | .782 | .052 | 22.568 | *** | ||||

| DM5 | .709 | |||||||

| Continuous Improvement | .873 | .878 | .644 | |||||

| CI1 | .698 | |||||||

| CI2 | .845 | .044 | 25.115 | *** | ||||

| CI3 | .832 | .043 | 24.785 | *** | ||||

| CI4 | .827 | .045 | 24.665 | *** | ||||

| Customer Focus | .876 | .877 | .587 | |||||

| CF2 | .752 | |||||||

| CF3 | .784 | .044 | 25.473 | *** | ||||

| CF4 | .76 | .043 | 24.633 | *** | ||||

| CF6 | .808 | .045 | 26.281 | *** | ||||

| CF7 | .727 | .044 | 23.474 | *** | ||||

| Employee Involvement | .917 | .918 | .738 | |||||

| EI2 | .865 | .035 | 31.746 | *** | ||||

| EI3 | .881 | .034 | 32.508 | *** | ||||

| EI4 | .901 | .033 | 33.466 | *** | ||||

| EI5 | .786 | |||||||

| Process Management | .847 | .871 | .580 | |||||

| PM1 | .781 | .060 | 17.285 | *** | ||||

| PM2 | .818 | .063 | 17.681 | *** | ||||

| PM3 | .801 | .060 | 17.507 | *** | ||||

| PM4 | .837 | .062 | 17.865 | *** | ||||

| PM5 | .532 | |||||||

| Relations with Suppliers | .923 | .925 | .756 | |||||

| RS2 | .809 | .029 | 35.181 | *** | ||||

| RS3 | .904 | .024 | 43.952 | *** | ||||

| RS4 | .894 | |||||||

| RS5 | .869 | .024 | 40.475 | *** | ||||

| Financial Performance | .893 | .895 | .810 | |||||

| FP1 | .856 | |||||||

| FP2 | .943 | .040 | 26.947 | *** | ||||

| Operational-Quality Performance | .879 | .879 | .593 | |||||

| OQP3 | .757 | .036 | 26.481 | *** | ||||

| OQP4 | .745 | .036 | 25.932 | *** | ||||

| OQP5 | .762 | .035 | 26.695 | *** | ||||

| OQP6 | .779 | .036 | 27.434 | *** | ||||

| OQP8 | .806 |

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Leadership | 3.68 | .784 | ||||||||

| 2. Decision Making | 3.77 | .739 | .761** | |||||||

| 3. Continuous Improvement | 3.82 | .802 | .583** | .558** | ||||||

| 4. Customer Focus | 3.94 | .721 | .545** | .482** | .616** | |||||

| 5. Employee Involvement | 3.20 | .969 | .619** | .570** | .584** | .530** | ||||

| 6. Process Management | 3.71 | .781 | .563** | .627** | .672** | .496** | .526** | |||

| 7. Relations with Suppliers | 3.46 | .902 | .527** | .523** | .509** | .550** | .644** | .548** | ||

| 8. Financial Performance | 3.64 | .952 | .434** | .394** | .431** | .512** | .401** | .405** | .411** | |

| 9.Operational-Quality Performance | 3.75 | .719 | .571** | .536** | .549** | .651** | .530** | .493** | .576** | .531** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).