Submitted:

04 September 2023

Posted:

06 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental site and plant materials

2.2. Treatments and experimental design

2.3. Growth and herb yield determination

2.4. Assessment of total chlorophyll content

2.5. Essential oil determination

2.6. Essential oil composition

2.7. Determination of H2O2

2.8. Assessment of lipid peroxidation

2.9. Membrane permeability measurement

2.10. Determination of glutathione (GSH)

2.11. Proline determination

2.12. Determination of total phenol content

2.13. Determination of Antioxidant enzyme activities

2.14. Statistical analysis

3. Results

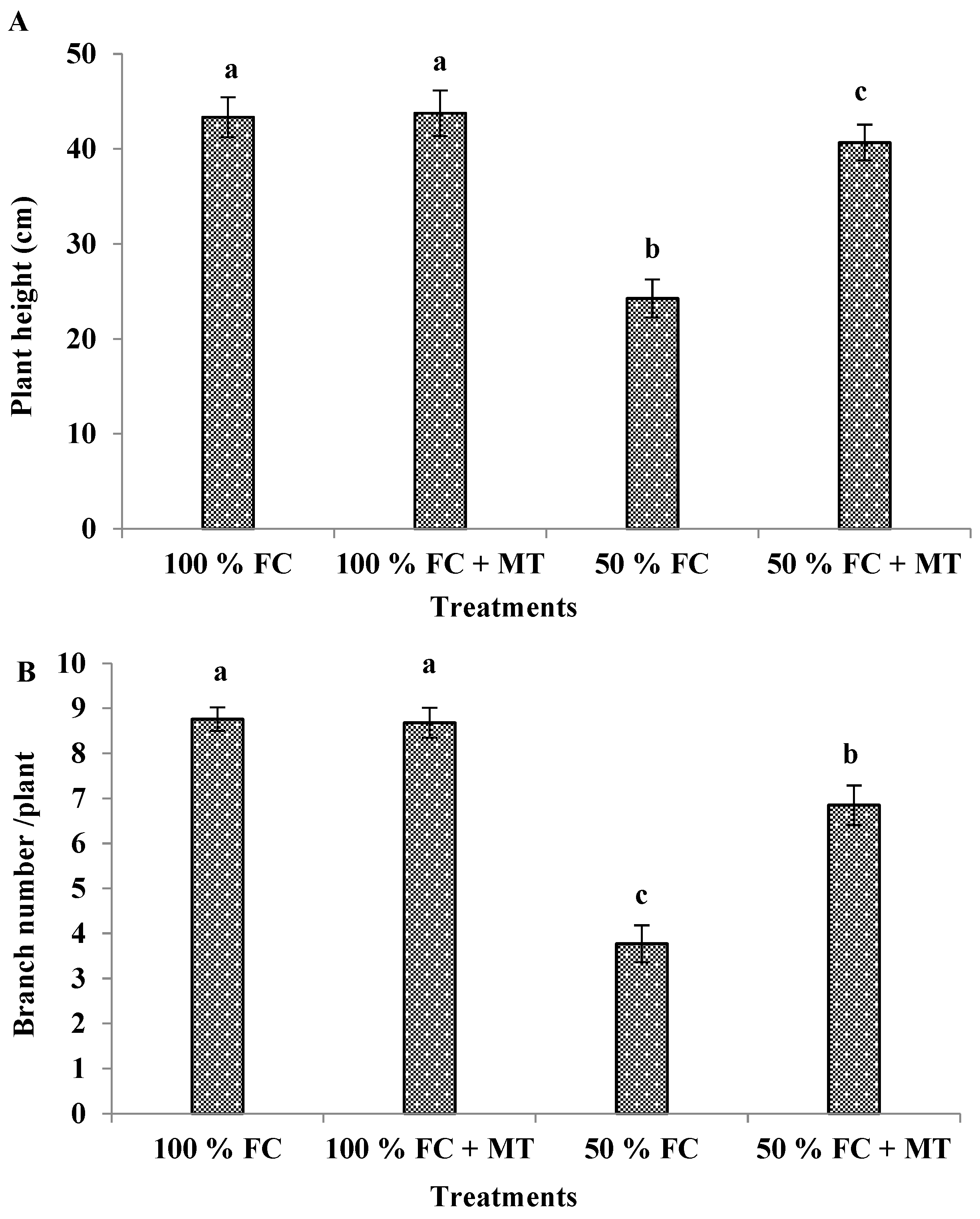

3.1. Growth characters and herb yield

3.2. Essential oil content

3.3. Essential oil composition

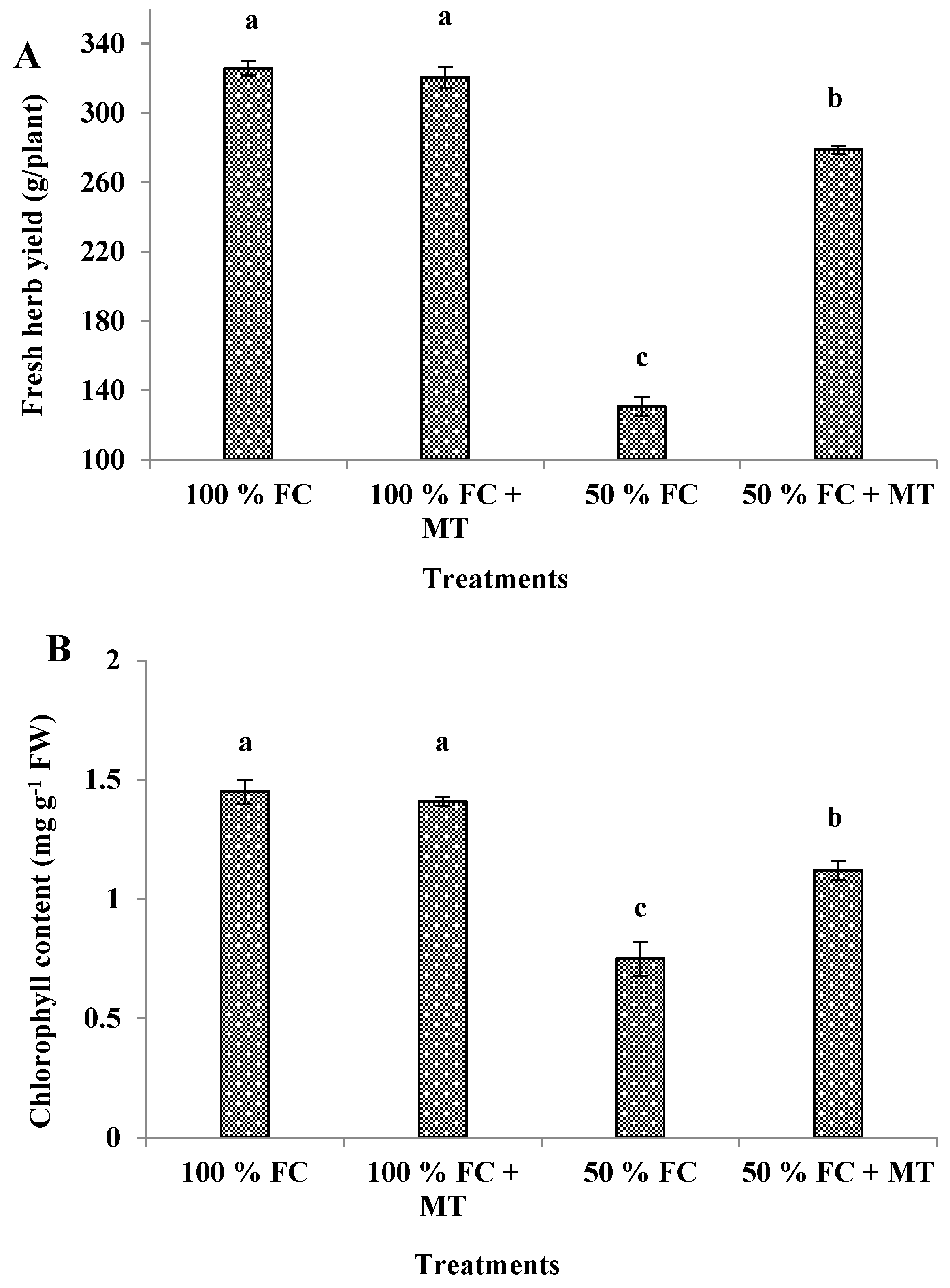

3.4. Chlorophyll content

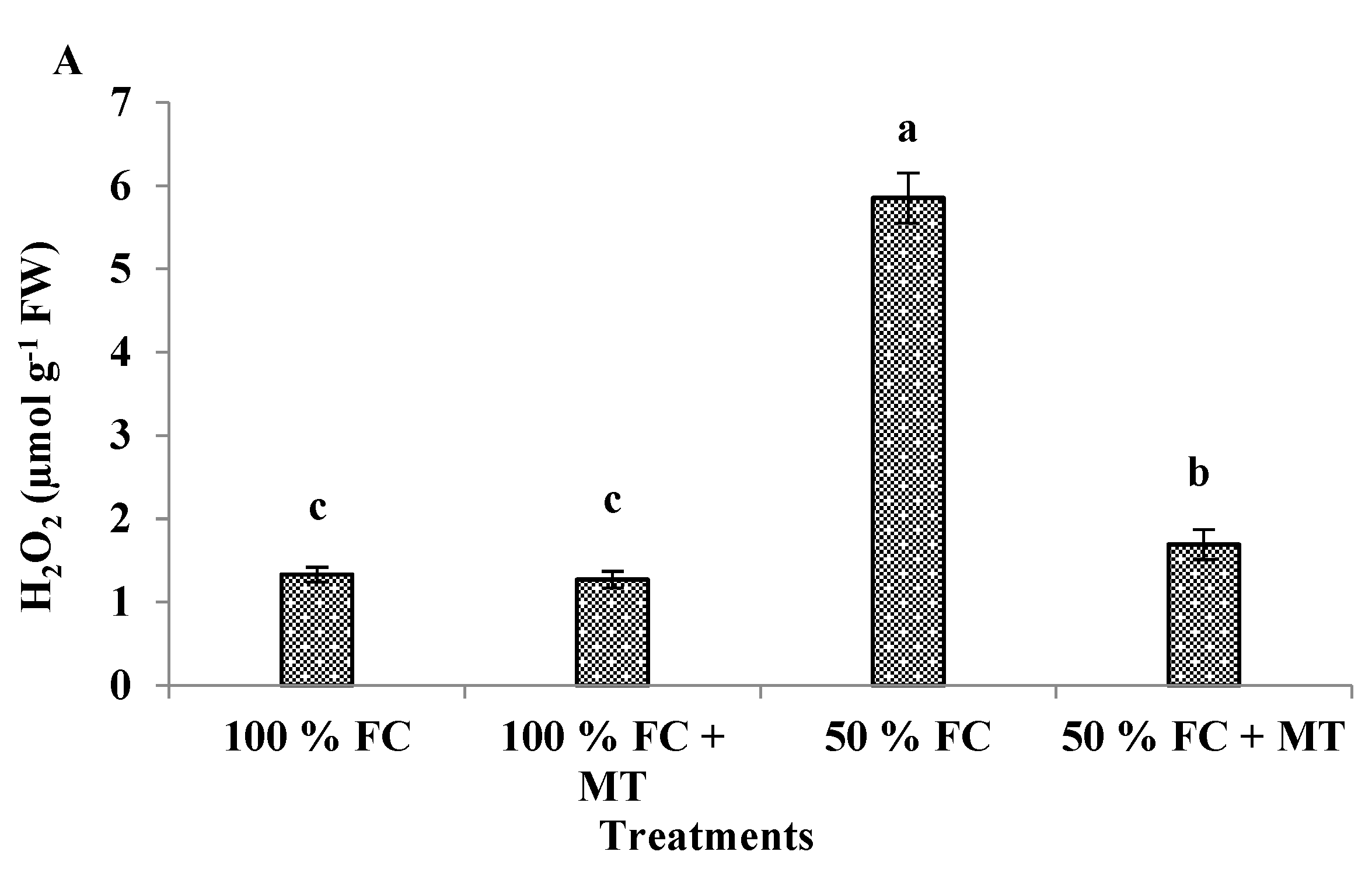

3.5. H2O2 production

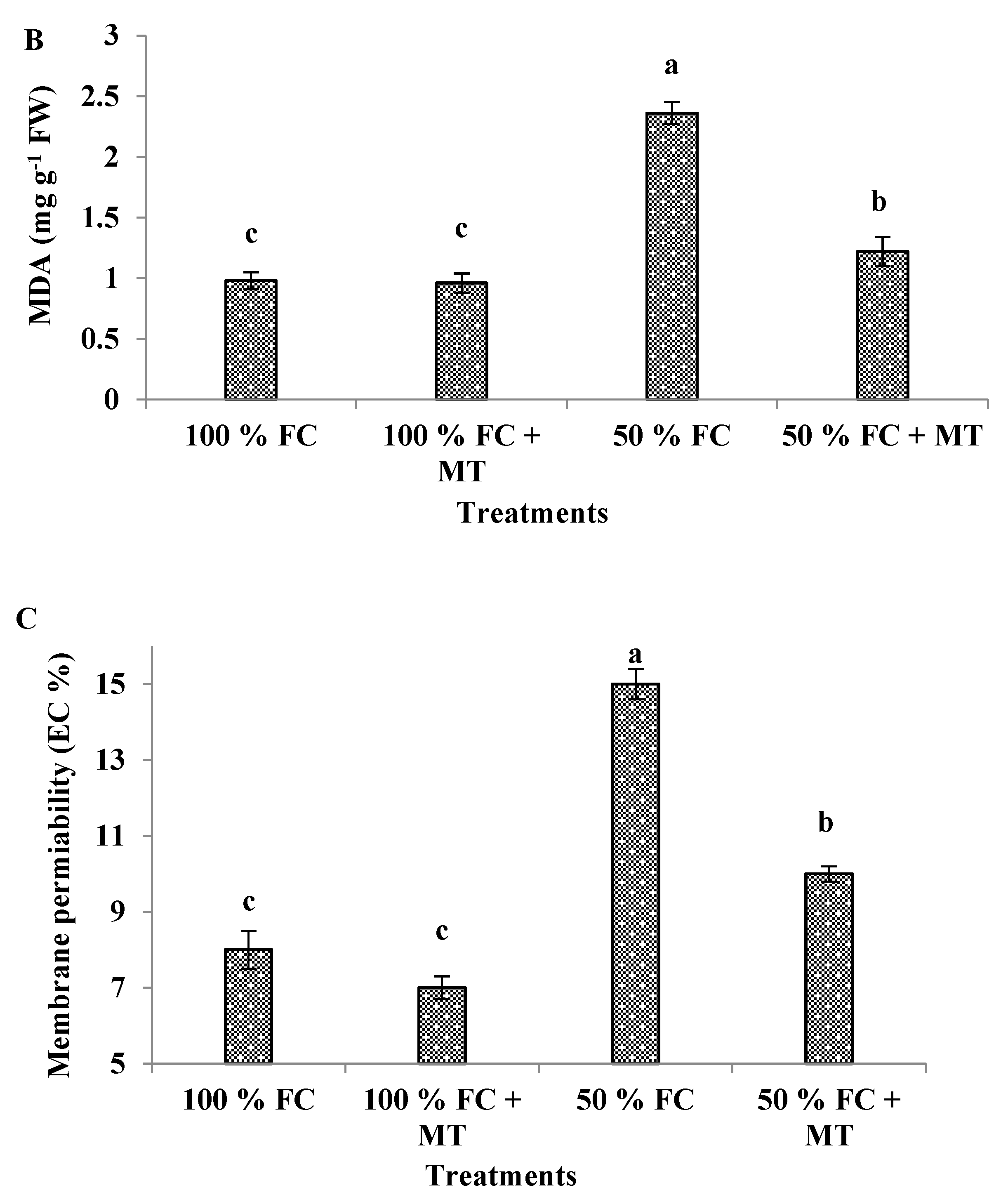

3.6. MDA content

3.7. Membrane permeability

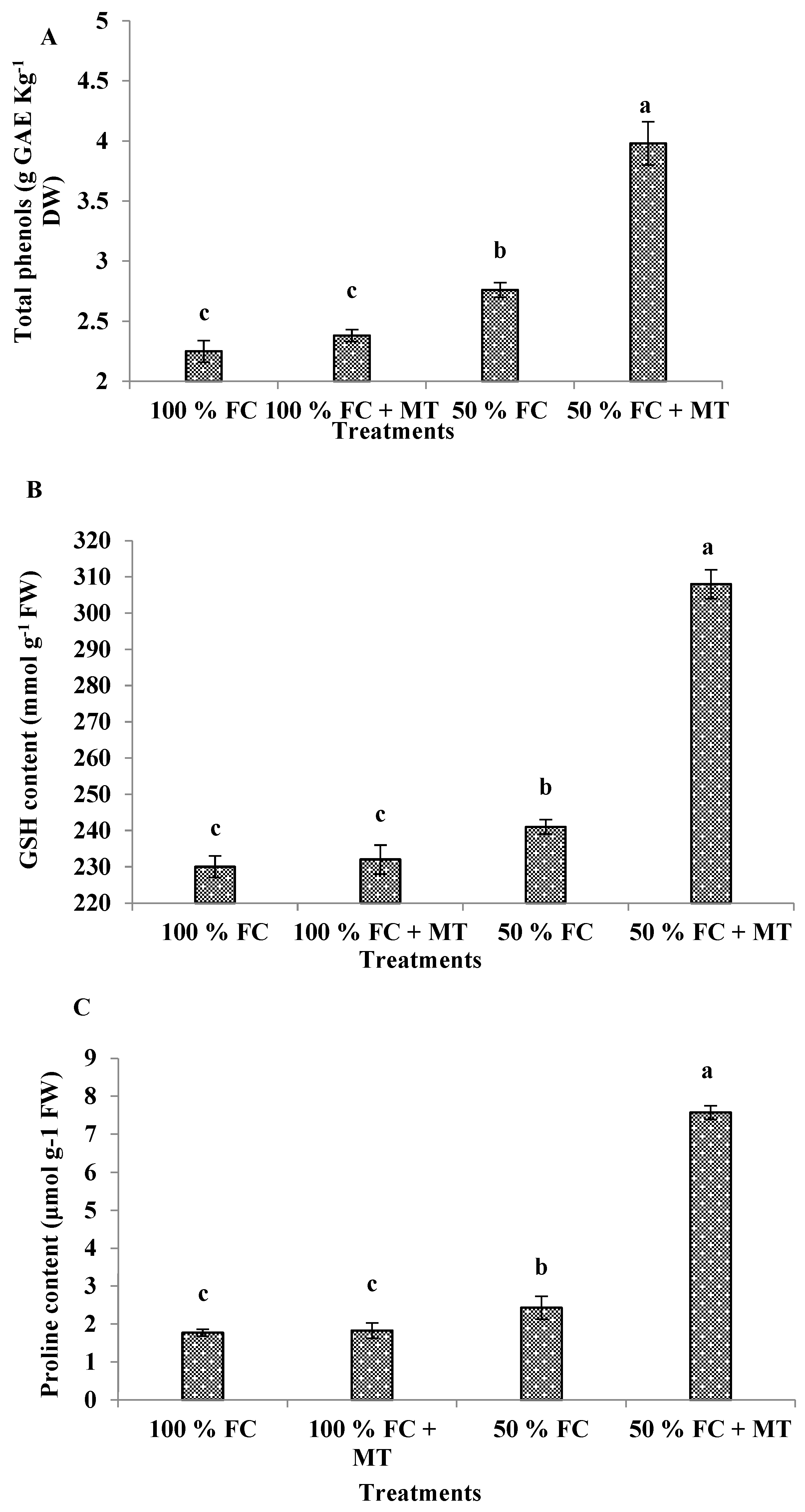

3.8. Total phenols

3.9. Glutathione (GSH) content

3.10. Proline

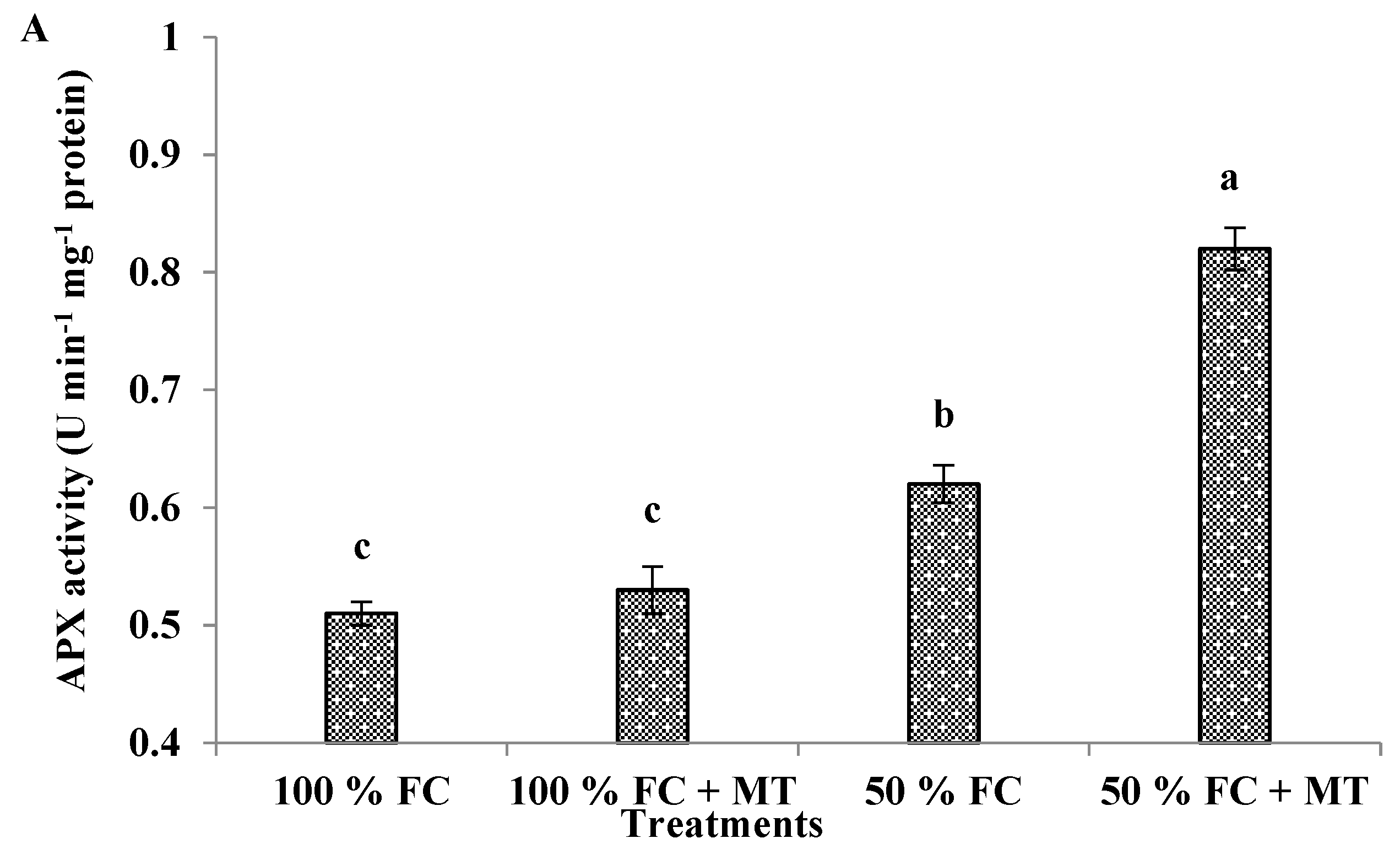

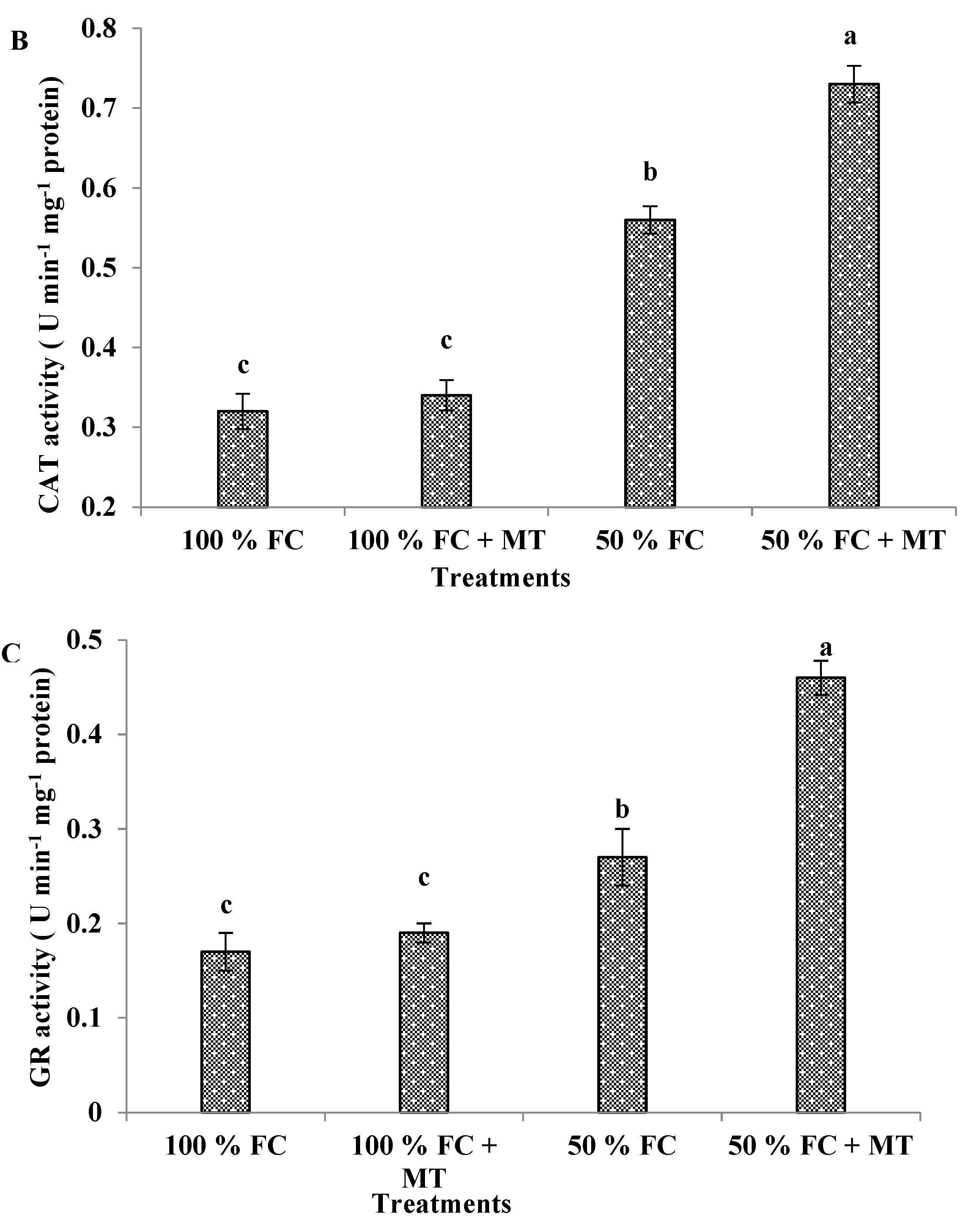

3.11. APX, CAT, and GR enzyme activities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mirajkar, S.J.; Dalvi, S.G.; Ramteke, S.D.; Suprasanna, P. Foliar application of gamma radiation processed chitosan triggered distinctive biological responses in sugarcane under water deficit stress conditions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 139, 1212–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, F.; Ali, E.F.; Mahfouz, S. Comparison between different fertilization sources, irrigation frequency and their combinations on the growth and yield of the coriander plant. Aust. J. Appl. Basic Sci. 2012, 6, 600–615. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, E.F.; Hassan, F.A.S. Water stress alleviation of roselle plant by silicon treatment through some physiological and biochemical responses. Annual Res. Rev. Biol. 2017, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, E.F.; El-Shehawi, A.M.; Ibrahim, O.H.M.; Abdul-Hafeez, E.Y.; Moussa, M.M.; Hassan, F.A.S. A vital role of chitosan nanoparticles in improvisation of the drought stress tolerance in Catharanthus roseus (L.) through biochemical and gene expression modulation. Plant Physiol. Biochem.

- Tabassum, S.; Ossola, A.; Marchin, R.M.; Ellsworth, D.S.; Leishman, M.R. Assessing the relationship between trait-based and horticultural classifications of plant responses to drought. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 61, 127109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaat, N.B.; Shawky, B.T.; Ibrahim, A.S. Alleviation of drought-induced oxidative stress in maize (Zea mays L.) plants by dual application of 24-epibrassinolide and spermine. Environ. Exp. Bot.

- Hassan, F.A.S.; Ali, E.F.; Alamer, K.H. Exogenous application of polyamines alleviates water stress-induced oxidative stress of Rosa damascena Miller var. trigintipetala Dieck. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2018, 116, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yasi, H.; Attia, H.; Alamer, K.; Hassan, F.; Esmat, F.; Elshazly, S.; Siddique, K.H.; Hessini, K. Impact of drought on growth, photosynthesis, osmotic adjustment, and cell wall elasticity in Damask rose. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 150, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, H.; Al-Yasi, H.; Alamer, K.; Esmat, F.; Hassan, F.; Elshazly, S.; Hessini, K. Induced anti-oxidation efficiency and others by salt stress in Rosa damascena Miller. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 274, 109681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, F.; Mazrou, R.; Gaber, A.; Hassan, M. Moringa extract preserved the vase life of cut roses through maintaining water relations and enhancing antioxidant machinery. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2020, 164, 111156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaleel, C.A.; Manivannan, P.; Sankar, B.; Kishorekumar, A.; Gopi, R.; Somasundaram, R.; Panneerselvam, R. Induction of drought stress tolerance by ketoconazole in Catharanthus roseus is mediated by enhanced antioxidant potentials and secondary metabolite accumulation. Coll. Surf. B: Biointerfaces.

- Jaleel, C.A.; Manivannan, P.; Sankar, B.; Kishorekumar, A.; Gopi, R.; Somasundaram, R.; Panneerselvam, R. . Water deficit stress mitigation by calcium chloride in Catharanthus roseus: Effects on oxidative stress, proline metabolism and indole alkaloid accumulation. Coll. Surf. B: Biointerfaces.

- Hassan, F.; Ali, E.; Al-Zahrany, O. Effect of amino acids application and different water regimes on the growth and volatile oil of Rosmarinus officinalis L. plant under Taif region conditions. Europ. J. Sci. Res. 2013, 1, 346–359. [Google Scholar]

- Amiri, R.; Nikbakht, A.; Etemadi, N. Alleviation of drought stress on rose geranium [Pelargonium graveolens (L.) Herit.] in terms of antioxidant activity and secondary metabolites by mycorrhizal inoculation. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 197, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatcher, C. R.; Ryves, D.B.; Millett, J. The function of secondary metabolites in plant carnivory. Ann. Bot. 2020, 125, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayati, P.; Karimmojeni, H.; Razmjoo, J. Changes in essential oil yield and fatty acid contents in black cumin (Nigella sativa L.) genotypes in response to drought stress. Ind. Crops Prod, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidabadi, S.S.; Van der Weide, J.; Sabbatini, P. Exogenous melatonin improves glutathione content, redox state and increases essential oil production in two Salvia species under drought stress. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 6883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulak, M. Recurrent drought stress effects on essential oil profile of Lamiaceae plants: An approach regarding stress memory. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 154, 112695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Shahsavar, A. The effect of foliar application of melatonin on changes in secondary metabolite contents in two citrus species under drought stress conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 692735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, F.; Al-Yasi, H.; Ali, E.F.; Alamer, K.; Hessini, K.; Attia, H.; El-Shazly, S. Mitigation of salt stress effects by moringa leaf extract or salicylic acid through motivating antioxidant machinery in damask rose. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2021, 101, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkarmout, A.F.; Yang, M.; Hassan, F.A. Chitosan treatment effectively alleviates the adverse effects of salinity in Moringa oleifera Lam via enhancing antioxidant system and nutrient homeostasis. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R.J.; Tan, D.X.; Zhou, Z.; Cruz, M.H.; Fuentes-Broto, L.; Galano, A. Phytomelatonin: assisting plants to survive and thrive. Molecules 2015, 20, 7396–7437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, L.; Wu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Ban, Z.; Li, L.; Li, X. Insights into exogenous melatonin associated with phenylalanine metabolism in postharvest strawberry. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2020, 168, 111244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Hu, J. Melatonin: Current status and future perspectives in horticultural plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1140803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ruiz, J.; Arnao, M. B. Relationship of melatonin and salicylic acid in biotic/abiotic plant stress responses. Agronomy 2018, 8, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnao, M.B.; Hernández-Ruiz, J. Melatonin: A new plant hormone and/or a plant master regulator? Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnao, M.B.; Hernández-Ruiz, J. Melatonin in flowering, fruit set and fruit ripening. Plant Reproduction 2020, 33, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharif, R.; Xie, C.; Zhang, H.; Arnao, M.B.; Ali, M.; Ali, Q.; Muhammad, I.; Shalmani, A.; Nawaz, M.; Chen, P.; Li, Y. Melatonin and its effects on plant systems. Molecules 2018, 23, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Sun, Q.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, L.; Qi, Y.; Ren, S.; Zhao, B.; Guo, Y.D. Melatonin improved anthocyanin accumulation by regulating gene expressions and resulted in high reactive oxygen species scavenging capacity in cabbage. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, B.; Islam, W.; Li, M.; Sun, Y.T.; Lu, X.C.; Mitra, S.; Hussain, M.; Liu, S.; Qiuet, D. Melatonin mediates enhancement of stress tolerance in plants. Int. J. Molec. Sci. 2019, 20, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.J.; Zhang, N.; Yang, R.C.; Wang, L.; Sun, Q.Q.; Li, D.B.; Cao, Y.; Weeda, S.; Zhao, B.; Ren, S.; Guo, Y. Melatonin promotes seed germination under high salinity by regulating antioxidant systems, ABA and GA4 interaction in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). J. Pineal Res. 2014, 57, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Tan, D.X.; Liang, D.; Chang, C.; Jia, D.; Ma, F. Melatonin mediates the regulation of ABA metabolism, free-radical scavenging, and stomatal behaviour in two Malus species under drought stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 2015 66, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabiri, R.; Hatami, A.; Oloumi, H.; Naghizadeh, M.; Nasibi, F.; Tahmasebi, Z. Foliar application of melatonin induces tolerance to drought stress in Moldavian balm plants (Dracocephalum moldavica) through regulating the antioxidant system. Folia Hortic. 2018, 30, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N.; Zhang, J.; Luo, T.; Liu, J.; Rizwan, M.; Fahad, S.; Xu, Z.; Hu, L. Seed priming with melatonin coping drought stress in rapeseed by regulating reactive oxygen species detoxification: Antioxidant defense system, osmotic adjustment, stomatal traits and chloroplast ultrastructure perseveration. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 2019 140, 111597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Wan, H.; Jiang, F.; Li, X.; Yu, X.; Rosenqvist, E.; Ottosen, C. The alleviation of photosynthetic damage in tomato under drought and cold stress by high CO2 and melatonin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.; Samsampour, D.; Zahedi, S.; Zamanian, K.; Rahman, M.; Mostofa, M.; Tran, L. Melatonin alleviates drought impact on growth and essential oil yield of lemon verbena by enhancing antioxidant responses, mineral balance, and abscisic acid content. Physiologia Plantarum 2021, 172, 1363–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.; Singh, U.B.; Ram, M.; Yadav, A.; Chanotiya, C.S. Biomass yield, essential oil yield and quality of geranium (Pelargonium graveolens L. Her.) as influenced by intercropping with garlic (Allium sativum, L.) under subtropical and temperate climate of India. Ind. Crop. Prod.

- Rajeswara Rao, B.R. Biomass yield, essential oil yield and essential oil composition, of rose-scented geranium (Pelargonium species) as influenced by row spacing and inter-cropping with corn mint (Mentha arvensis L. f. piperascens Malinv. Ex Holmes). Ind. Crop. Prod. 2002, 16, 133–144. [Google Scholar]

- Boukhris, M.; Hadrich, F.; Chtourou, H.; Dhouib, A.; Bouaziz, M.; Sayadi, S. Chemical composition, biological activities and DNA damage protective effect of Pelargonium graveolens L’Hér. essential oils at different phenological stages. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2015, 74, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machalova, Z.; Sajfrtova, M.; Pavela, R.; Topiar, M. Extraction of botanical pesticides from Pelargonium graveolens using supercritical carbon dioxide. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2015, 67, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.Y.; Na, S.S.; Kim, Y.K. Effects of oral care with essential oil on improvement in oral health status of hospice patients. J. Kor. Acad. Nurs. 2010, 40, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraswathi, J.; Venkatesh, K.; Baburao, N.; Hilal, M.H.; Rani, A.R. Phytopharmacological importance of Pelargonium species. J. Med. Plant Res. 2011, 5, 2587–2598. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, V.; Patra, D.D. Crop productivity, aroma profile and antioxidant activity in Pelargonium graveolens L’Her. under integrated supply of various organic and chemical fertilizers. Ind. Crop Prod. 2015, 67, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, E.F.; Hassan, F.A.S.; Elgimabi, M. Improving the growth, yield and volatile oil content of Pelargonium graveolens L. Herit by foliar application with moringa leaf extract through motivating physiological and biochemical parameters. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2018, 119, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmeidani, A.; Jafari, A. A.; Mirza, M. Studying drought tolerance in Thymus kotschyanus accessions for cultivation in dryland farming and low efficient grassland. J. Range. Sci. 2017, 7, 331–340. [Google Scholar]

- Metzner, H.; Rau, H.; Senger, H. Unter suchungen zur synchronisier barteit einzelner pigmentan angel mutanten von chlorela. Planta 1965, 65, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedibe, M.M.; Allemann, J. Yield and quality response of rose geranium (Pelargonium graveolens L.) to sulphur and phosphorus application. S. Afr. J. Plant Soil.

- Patterson, B.D.; Macrae, E.A.; Ferguson, I.B. Estimation of hydrogen peroxide in plant extracts using titanium (IV). Anal. Chem. 1984, 134, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, D.M.; Delong, J.M.; Forney, C.F.; Prange, R.K. Improving the thiobarbituric acidreactive-substances assay for estimating lipid peroxidation in plant tissue containing anthocyanin and other interfering compounds. Planta 1999, 207, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Dai, Q.; Liu, X.; Huang, S.; Wang, Z. Flooding-induced membrane damage, lipid oxidation and activated oxygen generation in corn leaves. Plant Soil. 1996, 179, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.E. Determination of glutathione and glutathione disulfide in biological samples. Methods Enzymol. 1985, 113, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazrou, R.M.; Hassan, S.; Yang, M.; Hassan, F.A.S. Melatonin Preserves the Postharvest Quality of Cut Roses through Enhancing the Antioxidant System. Plants 2022, 11, 2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S.; Prenzler, P.D.; Antolovich, M.; Robards, K. Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of olive extracts. Food Chem. 2001, 73, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandlee, J.M.; Scandalios, J.G. Analysis of variants affecting the catalase developmental program in maize scutellum. Theoret. Appl. Genet. 1984, 69, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Asada, K. Hydrogen Peroxide is Scavenged by Ascorbate-specific Peroxidase in Spinach Chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981, 22, 867–880. [Google Scholar]

- Foyer, C.H.; Halliwell, B. The presence of glutathione and glutathione reductase in chloroplasts: A proposed role in ascorbic acid metabolism. Planta 1976, 133, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, M.V. Cellular detoxifying mechanisms determine the age dependent injury in tropical trees exposed to SO2. J. Plant Physiol. 1992, 140, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinisch, O. 1962 In: Steel, R.G.D., and J.H. Torrie. Principles and Procedures of Statistics. (With special Reference to the Biological Sciences.) McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York, Toronto, London 1960, 481 S., 15 Abb.; 81 s 6 d. Biometrische Zeitschrift 4, 207-208.

- Cui, G.; Zhao, X.; Liu, S.; Sun, F.; Zhang, C.; Xi, Y. Beneficial effects of melatonin in overcoming drought stress in wheat seedlings. Plant Physiol Biochem 2017, 118, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Wu, L.; Naeem, M.S.; Liu, H.; Deng, X.; Xu, L.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, W. 5-Aminolevulinic acid enhances photosynthetic gas exchange, chlorophyll fluorescence and antioxidant system in oilseed rape under drought stress. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2013, 35, 2747–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulugeta, S.M.; Radácsi, P. Influence of Drought Stress on Growth and Essential Oil Yield of Ocimum Species. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadak, M.; Abdalla, A.; Abd Elhamid, E.; Ezzo, M. Role of melatonin in improving growth, yield quantity and quality of Moringa oleifera L. plant under drought stress. Bullet. National Res. Center 2020, 44, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Z.; Bai, Q.; He, J.; Wang, Y. Effects of melatonin on antioxidant capacity in naked oat seedlings under drought stress. Molecules 2018, 23, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadak, M.; Bakry, B. Alleviation of drought stress by melatonin foliar treatment on two flax varieties under sandy soil. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2020, 26, 907–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoufan, P.; Bavani, M.R.; Rahnama, A. Effect of exogenous melatonin on improving of chlorophyll content and photochemical efficiency of PSII in mallow plants (Malva parviflora L.) treated with cadmium. Physiol. Mole. Pathol. Plants.

- Golkar, P.; Taghizadeh, M.; Yousefian, Z. The effects of chitosan and salicylic acid on elicitation of secondary metabolites and antioxidant activity of safflower under in vitro salinity stress. Plant Cell Tiss. Org. Cult. 2019, 137, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, F.A.S.; Morsi, M.M.; Aljoudi, N.G.S. Alleviating the Adverse Effects of Salt Stress in Rosemary by Salicylic Acid Treatment. Res. J. Pharma. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 1980–1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sarrou, E.; Chatzopoulou, P.; Dimassi-Teriou, K.; Terios, L.; Koularmani, A. Effect of melatonin, salicylic acid and gibberellic acid on leaf essential oil and other secondary metabolites of bitter orange young seedlings. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2015, 27, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Llorca, M.; Muñoz, P.; Müller, M.; Munné-Bosch, S. Biosynthesis, Metabolism and Function of Auxin, Salicylic Acid and Melatonin in Climacteric and Non-climacteric Fruits. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, S.; Sato, A.; Lage, C.; Gil, R.; Azevedo, D.; Esquibel, M. Essential oil composition of Melissa officinalis L. in vitro produced under the infuence of growth regulators. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2005, 16, 1387–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazzoumi, Z.; Moustakime, Y.; Amrani Joutei, K. Effect of gibberellic acid (GA), indole acetic acid (IAA) and benzylaminopurine (BAP) on the synthesis of essential oils and the isomerization of methyl chavicol and trans-anethole in Ocimum gratissimum L. SpringerPlus 2014, 3, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R. () ROS are good. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M. , Mostofa, M.G., Keya, S.S., Rahman, A., Das, A.K., Islam, R.; Abdelrahman, M., Bhuiyan, S., Naznin, T., Ansary, M., Eds.; Tran, L. Acetic acid improves drought acclimation in soybean: an integrative response of photosynthesis, osmoregulation, mineral uptake and antioxidant defense. Physiologia Plantarum 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J. F.; Xu, T.; Wang, Z.; Fang, Y.; Xi, Z.; Zhang, Z. The ameliorative effects of exogenous melatonin on grape cuttings under water-deficient stress: antioxidant metabolites, leaf anatomy, and chloroplast morphology. J. Pineal Res. 2014, 57, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, F.A.S.; Ali, E.; Gaber, A.; Fetouh, M.; Mazrou, R. Chitosan nanoparticles effectively combat salinity stress by enhancing antioxidant activity and alkaloid biosynthesis in Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don. Plant Physiol. Biochem.

- Hessini, K.; Wasli, H.; Al-Yasi, H.M.; Ali, E.F.; Issa, A.A.; Hassan, F.A.S.; Siddique, K.H.M. Graded moisture deficit effect on secondary metabolites, antioxidant, and inhibitory enzyme activities in leaf extracts of Rosa damascena Mill. var. trigentipetala. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, U.; Oba, S. Polyphenol and flavonoid profiles and radical scavenging activity in leafy vegetable Amaranthus gangeticus. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansour, M.M.F.; Salama, K.H.A. Proline and abiotic stresses: responses and adaptation. In: Plant Ecophysiology and Adaptation under Climate Change: Mechanisms and Perspectives II, Mechanisms of Adaptation and Stress Amelioration, Hasanuzzaman M, Ed., Springer, Singapore, 2020, pp. 357–397.

- Gan, J.; Feng, Y.; He, Z.; Li, H.; Zhang, H. Correlations between antioxidant activity and alkaloids and phenols of maca (Lepidium meyenii). J. Food Quality 2017, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatments | Essential oil (%) | Essential oil yield (mL/plant) |

|---|---|---|

| 100 % FC | 0.18 ± 0.03b | 0.59 ± 0.04b |

| 100 % FC + MT | 0.19 ± 0.02b | 0.61 ± 0.06b |

| 50 % FC | 0.23 ± 0.03a | 0.30 ± 0.04c |

| 50 % FC + MT | 0.24 ± 0.01a | 0.67 ± 0.03a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).