Submitted:

04 September 2023

Posted:

06 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

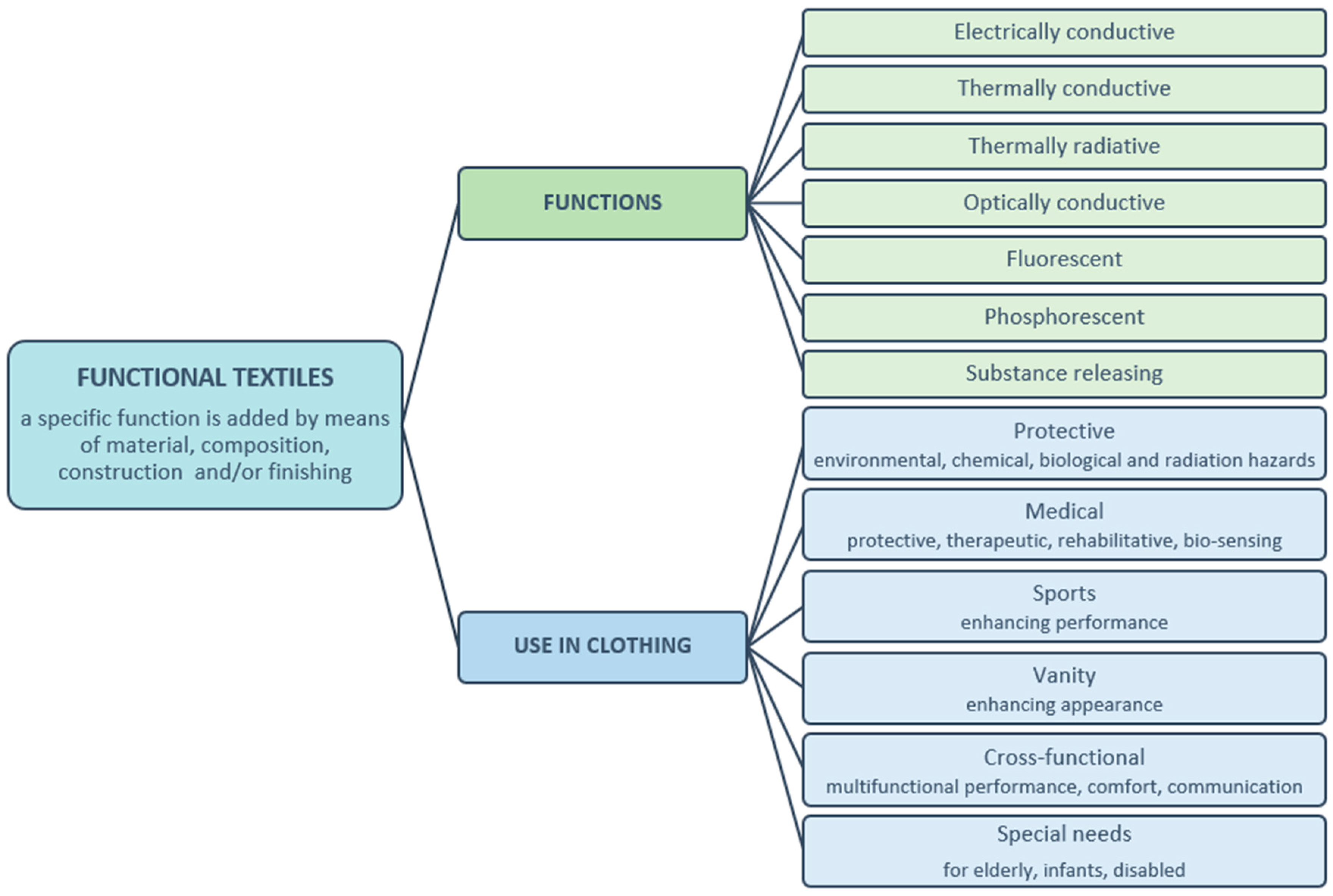

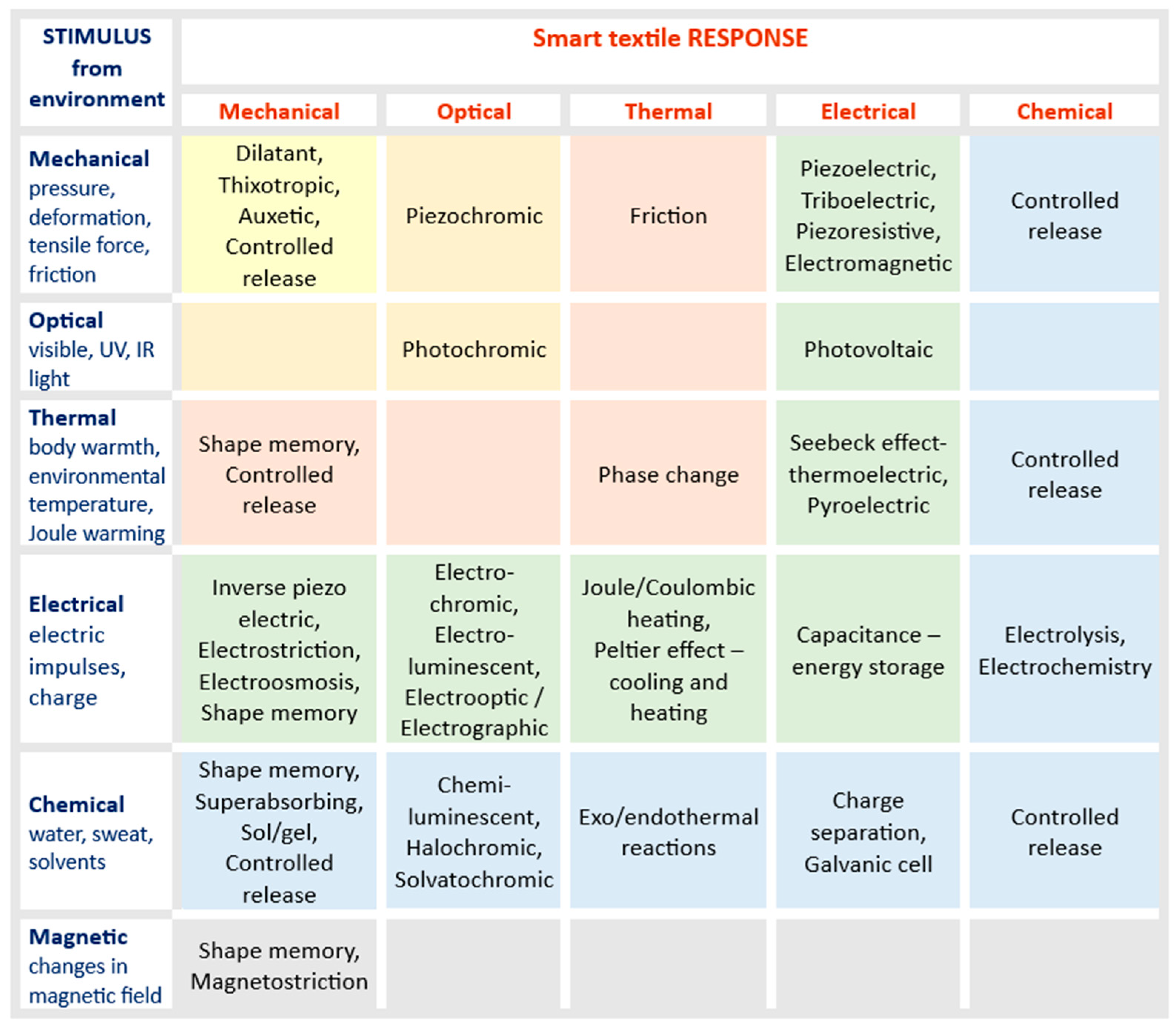

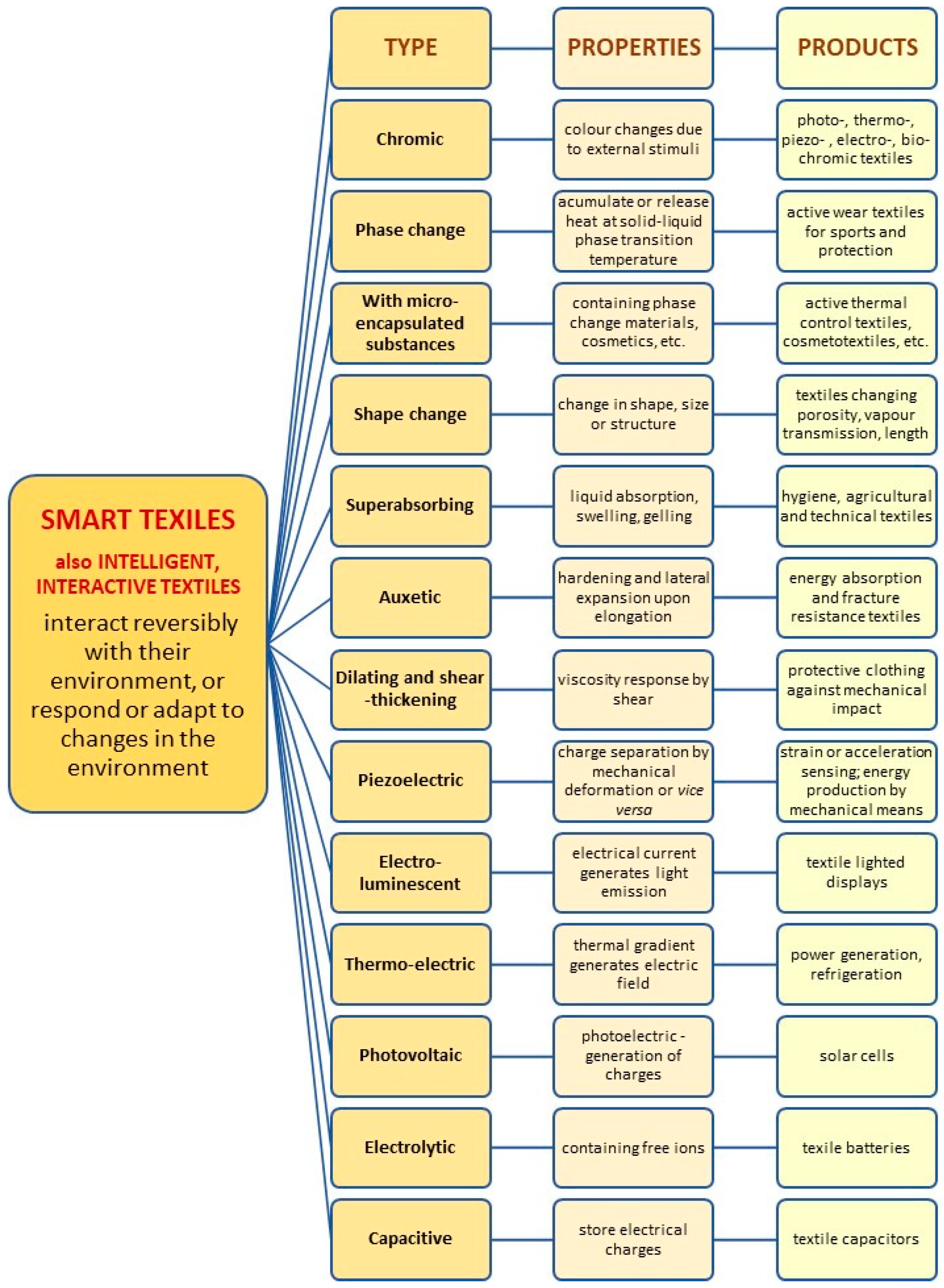

1.1. Definition and characteristics of smart textiles

- the first generation of smart textiles are referred to as passive smart textiles, with a sensing function only - their materials perceive external stimuli,

- the second generation are called active smart textiles, with an actuating function - they sense a stimulus from the environment and respond to it,

- the third generation is named the advanced or very smart or ultra smart textiles that perceive, respond and adapt to changes in the environment.

1.2. Related works

1.2.1. Reviews on smart textiles

1.2.2. Bibliometric mapping in the field of textiles

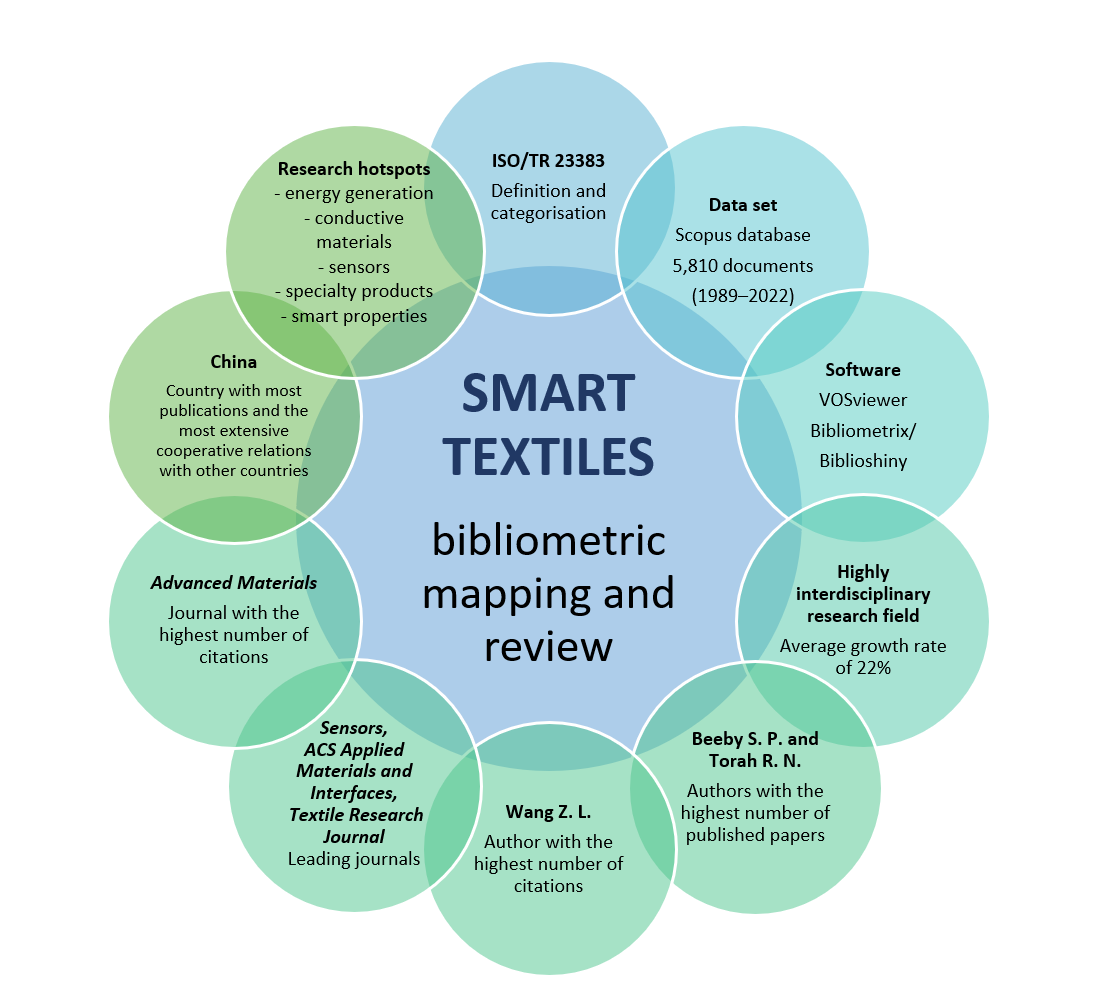

1.3. Aims and research questions

- RQ1: What are the global research outputs and publication trends?

- RQ2: What are the most relevant/influential documents, authors, sources and countries in the field of smart textiles?

- RQ3: What have been the main research topics, and what might be the focal points for future research?

- RQ4: What is the pattern of scientific collaboration on smart textiles at the country level?

2. Materials and methods

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Performance analysis

3.1.1. Overview of retrieved documents and trends

3.1.2. Analysis of oldest and most cited documents

3.1.3. Analysis of authors

3.1.4. Analysis of sources

3.1.5. Geographic distribution of the publications

3.2. Science mapping

3.2.1. Co-word analysis

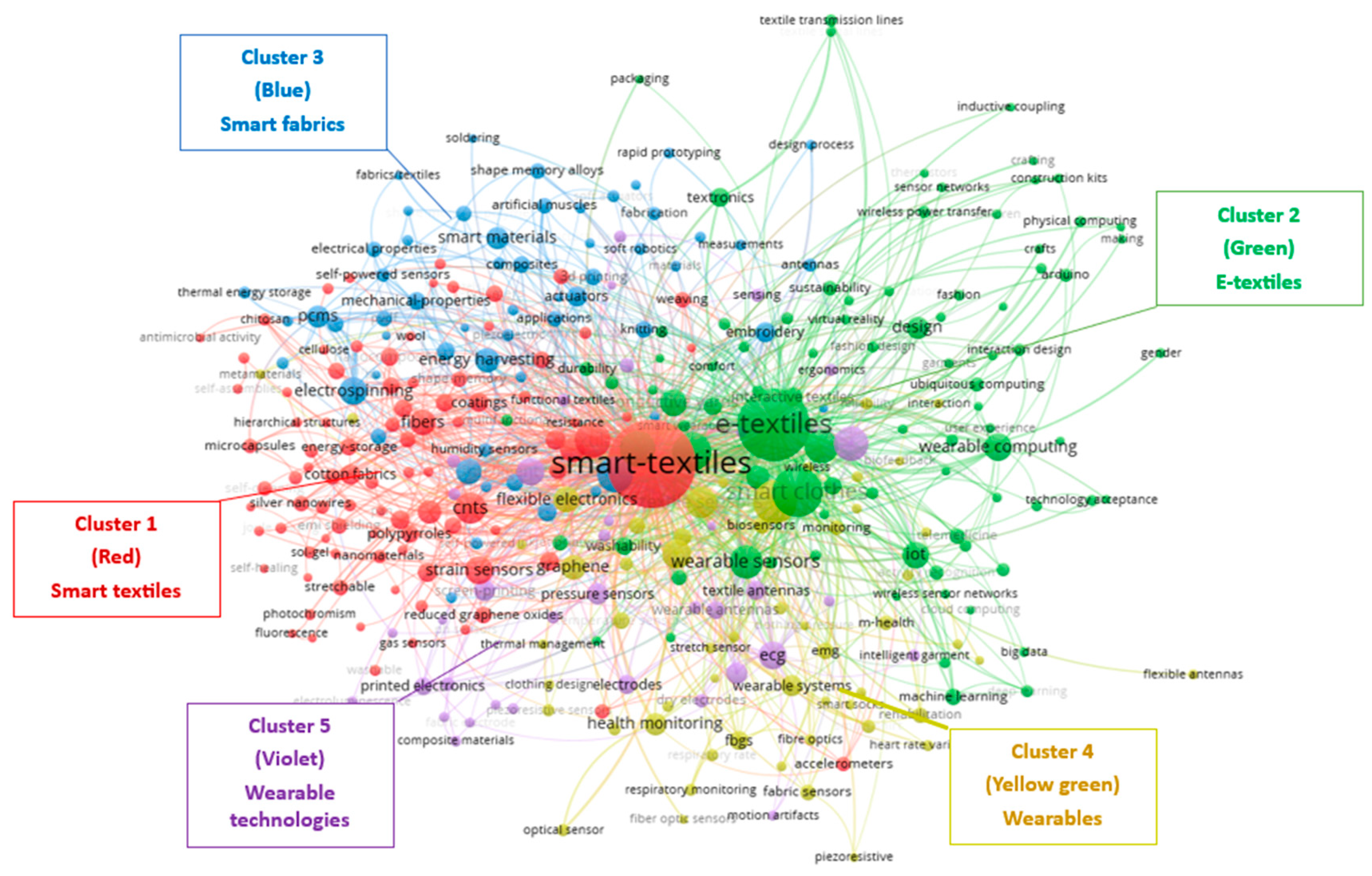

Clusters of KW as indicators of research areas

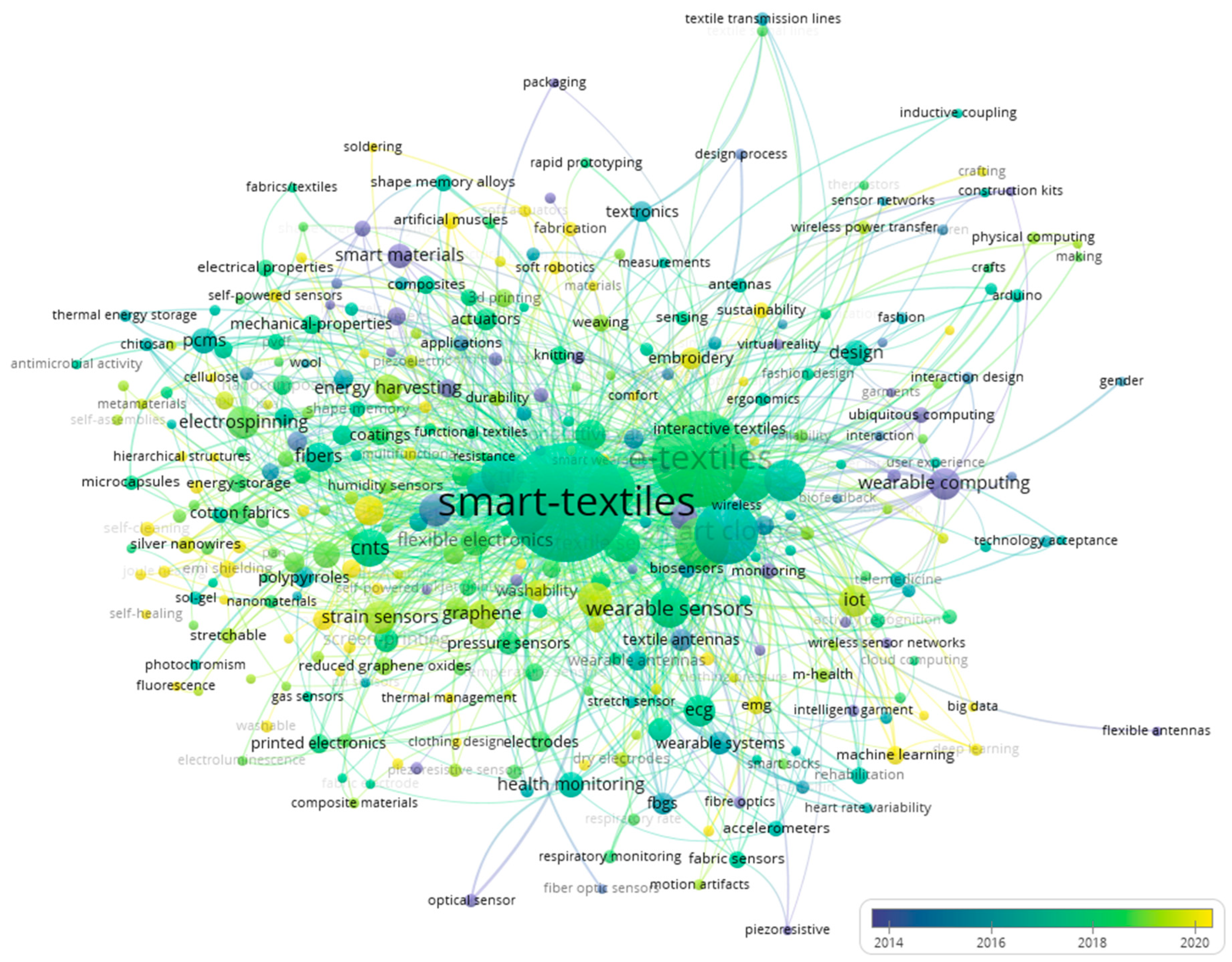

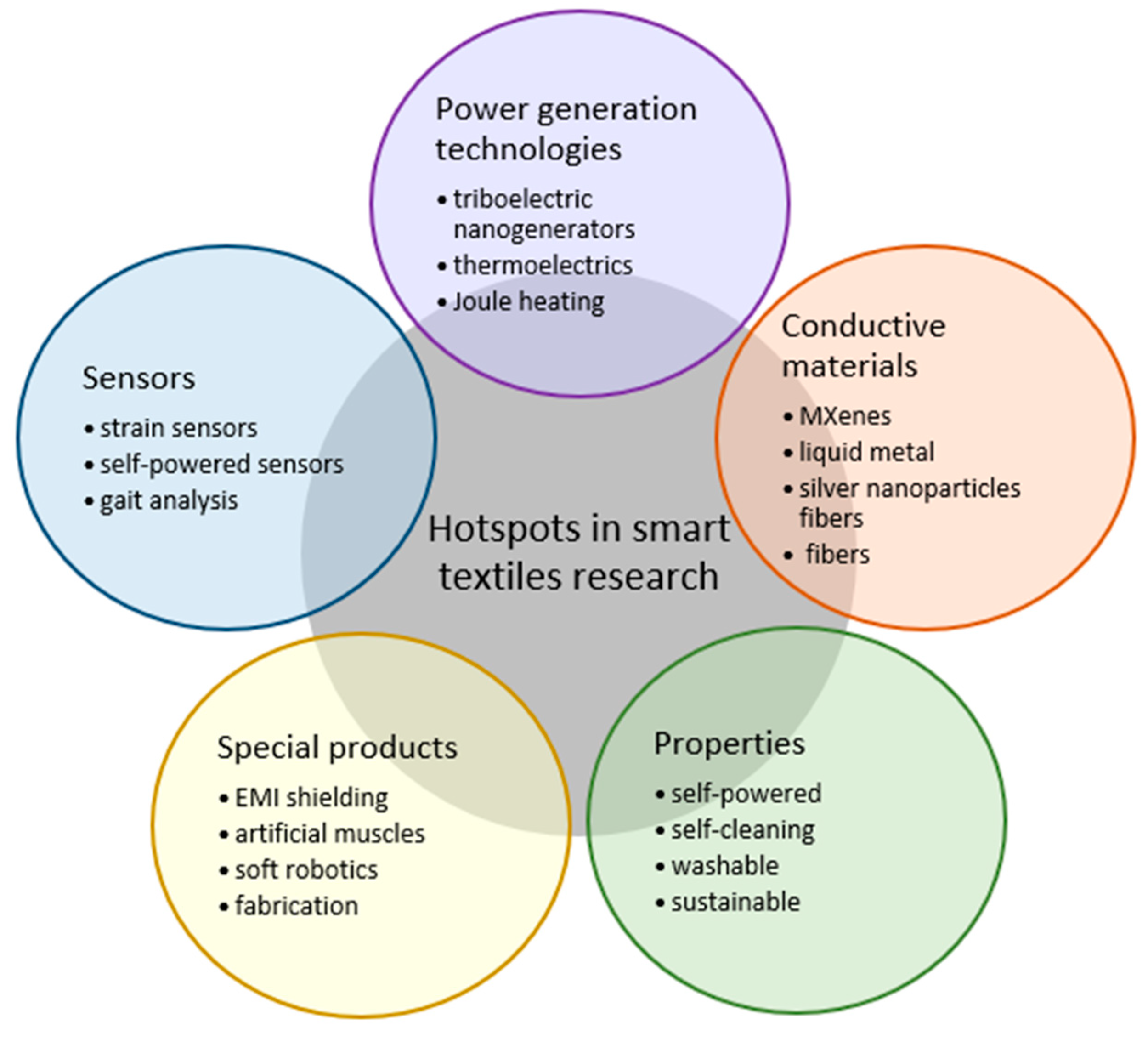

An overview of new trends - the latest concepts and propulsive research topics

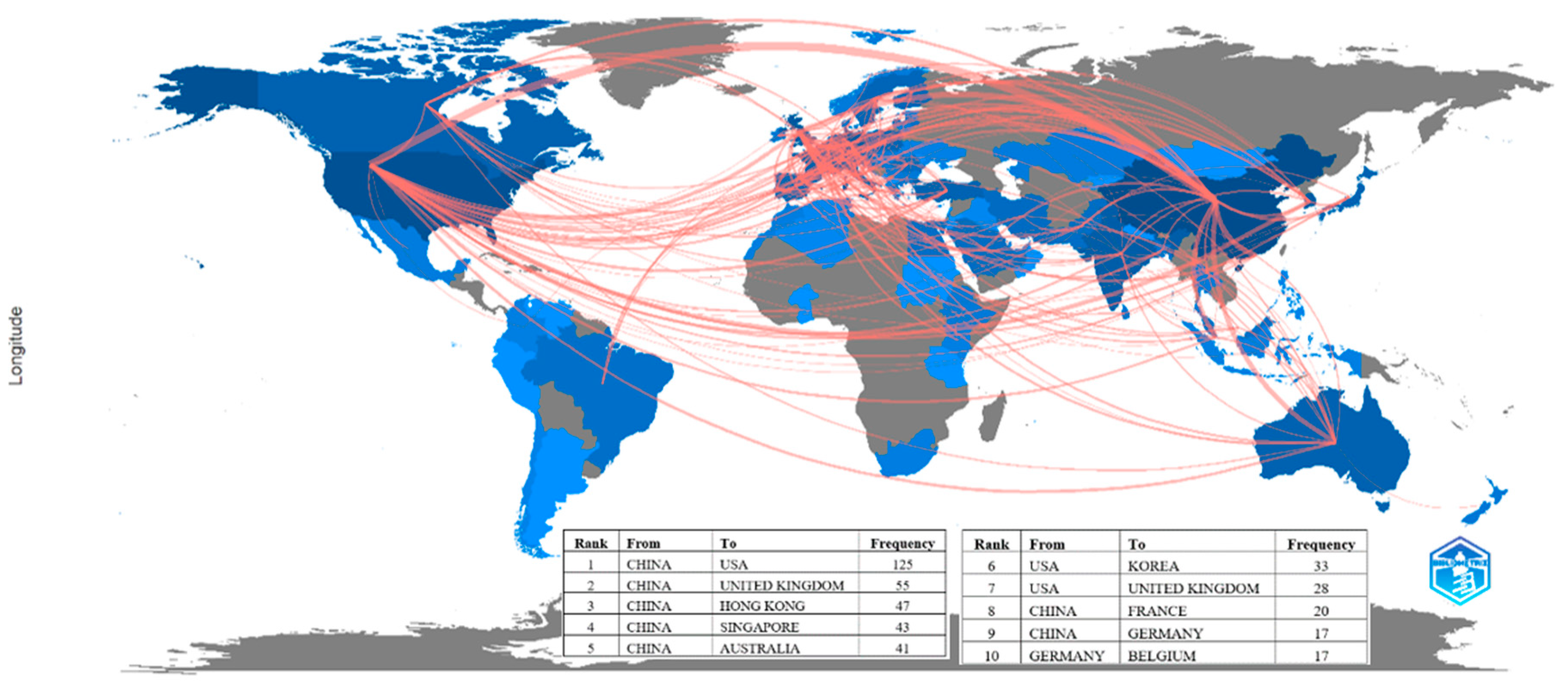

3.2.2. Co-authorship analysis of countries

3.3. Originality and limitations of the study

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rijavec, T. Standardisation of smart textiles. Glas. Hemičara Tehnol. Ekol. Repub. Srp. 2010, 4, 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Jin, P.; Yin, Y.; Yin, F. Mapping the knowledge domains of smart textile: visualization analysis-based studies. J. Text. Inst. 2022, 113, 2651–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, T. A Concept of intelligent materials. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 1990, 1, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, C.; McCabe, M.; Baggerman, C.; Potter, E. Smart Fabrics Technology Development: Final Report; NASA, 2010.

- Júnior, H.L.O.; Neves, R.M.; Monticeli, F.M.; Dall Agnol, L. Smart fabric textiles: recent advances and challenges. Textiles 2022, 2, 582–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, M.G.; Loghin, C.; Dulgheriu, I.; Loghin, E. Comfort evaluation of wearable functional textiles. Materials 2021, 14, 6466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, J.S.; Choi, S.B.; Jung, S.-B.; Kim, J.-W. Recent progress of Ti3C2Tx-Based MXenes for fabrication of multifunctional smart textiles. Appl. Mater. Today 2022, 29, 101612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, A.; Van Langenhove, L.; Guermonprez, P.; Deguillemont, D. A roadmap on smart textiles. Text. Prog. 2010, 42, 99–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syduzzaman, M.; Patwary, S.; Farhana, K.; Ahmed, S. Smart textiles and nano-technology: a general overview. J. Text. Sci. Eng. 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.A.; Pirzada, B.M.; Price, G.; Shibiru, A.L.; Qurashi, A. Applications of nanotechnology in smart textile industry: a critical review. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 38, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

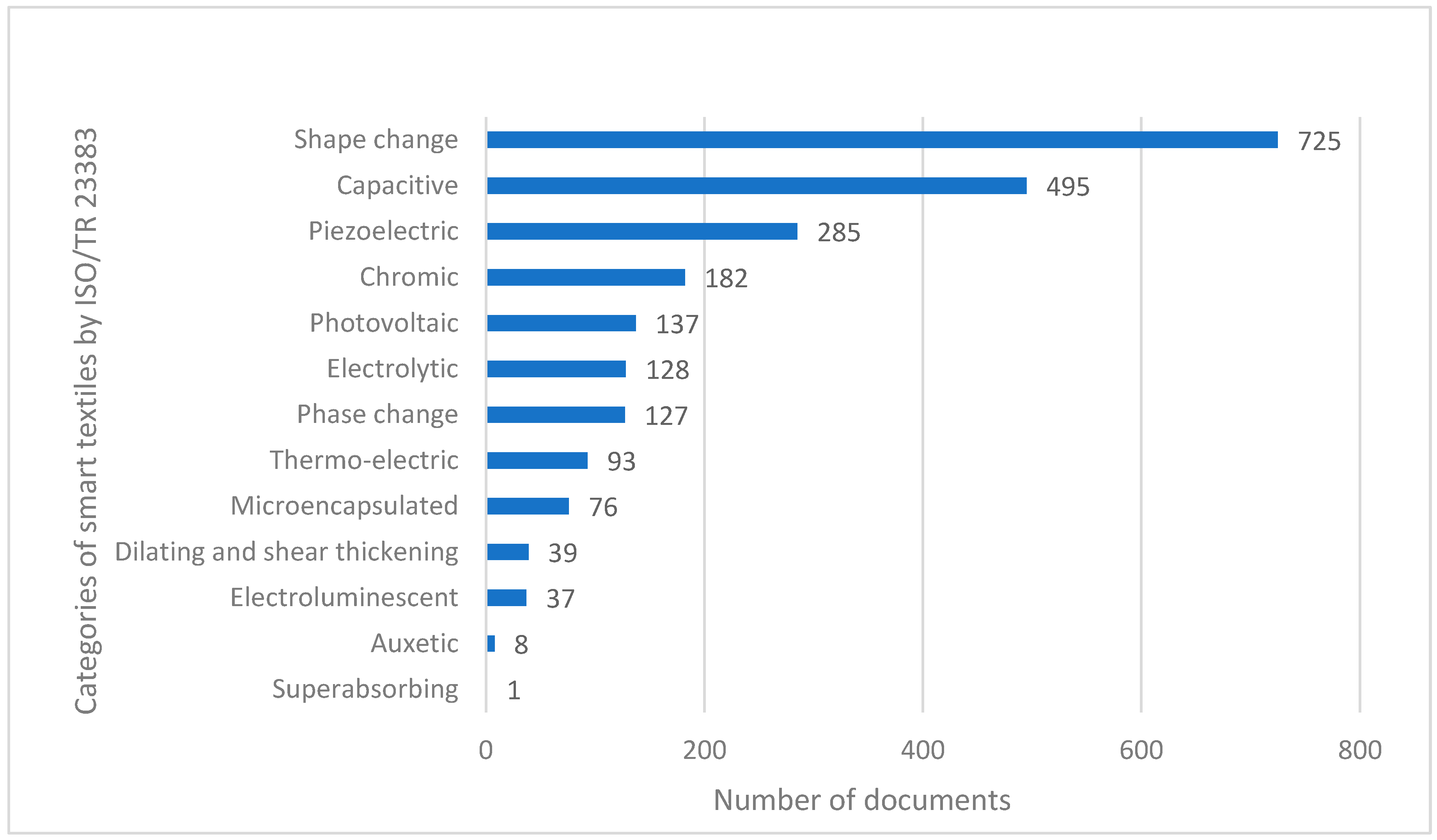

- ISO/TR 23383:2020. Textiles and textile products — Smart (Intelligent) textiles— Definitions, categorisation, applications and standardization needs.

- Gupta, D. Functional clothing— definition and classification. IJFTR 2011, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Libanori, A.; Chen, G.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, J. Smart textiles for personalized healthcare. Nat. Electron. 2022, 5, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.; Wang, Y.; Yang, R.; He, Z.; Tan, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liu, J.; Li, T. Self-powered smart textile based on dynamic schottky diode for human-machine interactions. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2207298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, K.; Hu, Y.; Yang, J.; Kim, S.-W.; Hu, W.; Wang, Z.L. Smart textile triboelectric nanogenerators: current status and perspectives. MRS Bull. 2021, 46, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart textiles market size, share, trends, global report 2023-2028. Available online: https://www.imarcgroup.com/smart-textiles-market (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Cherenack, K.; van Pieterson, L. Smart textiles: challenges and opportunities. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 112, 091301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehrke, I.; Tenner, V.; Lutz, V.; Schmelzeisen, D.; Gries, T. Smart Textiles Production: Overview of Materials, Sensor and Production Technologies for Industrial Smart Textiles; MDPI - Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 2019. ISBN 978-3-03897-497-0.

- Hu, J. Active Coatings for Smart Textiles; Woodhead Publishing, 2016. ISBN 978-0-08-100265-0.

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.; Li, Y. A Review of wearable carbon-based sensors for strain detection: fabrication methods, properties, and mechanisms. Text. Res. J. 2023, 93, 2918–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xiao, X.; Chen, G.; Zhao, X.; Chen, J. Self-powered sensing technologies for human metaverse interfacing. Joule 2022, 6, 1381–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda, A.; Hamza, M.F.; Shaheen, Th.I.; Wei, Y. Editorial: Nanotechnology and smart textiles: sustainable developments of applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, M.; Ungureanu, C. Green nanomaterials for smart textiles dedicated to environmental and biomedical applications. Materials 2023, 16, 4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaroni, C.; Saccomandi, P.; Schena, E. Medical smart textiles based on fiber optic technology: an overview. J. Funct. Biomater. 2015, 6, 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, F.; Cheng, Z.; Raad, R.; Xi, J.; Foroughi, J. Piezofibers to smart textiles: a review on recent advances and future outlook for wearable technology. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 9496–9522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, N.-K.; Martinez, J.G.; Zhong, Y.; Maziz, A.; Jager, E.W.H. Actuating textiles: next generation of smart textiles. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2018, 3, 1700397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongahage, D.; Foroughi, J. Actuator materials: review on recent advances and future outlook for smart textiles. Fibers 2019, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S. Phase change materials for smart textiles – an overview. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2008, 28, 1536–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, M.; Zia, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Reece, M.J.; Su, L. A Review of recent developments in smart textiles based on perovskite materials. Textiles 2022, 2, 447–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, C.; Hertleer, C.; Schwarz-Pfeiffer, A. 2 - smart textiles in health: an overview. In Smart Textiles and their Applications; Koncar, V., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Textiles; Woodhead Publishing: Oxford, 2016; pp. 9–32. ISBN 978-0-08-100574-3. [Google Scholar]

- Langenhove, L. van Advances in Smart Medical Textiles: Treatments and Health Monitoring; Woodhead Publishing, 2015. ISBN 978-1-78242-400-0.

- Kubicek, J.; Fiedorova, K.; Vilimek, D.; Cerny, M.; Penhaker, M.; Janura, M.; Rosicky, J. Recent trends, construction, and applications of smart textiles and clothing for monitoring of health activity: a comprehensive multidisciplinary review. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 15, 36–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelucci, A.; Cavicchioli, M.; Cintorrino, I.A.; Lauricella, G.; Rossi, C.; Strati, S.; Aliverti, A. Smart textiles and sensorized garments for physiological monitoring: a review of available solutions and techniques. Sensors 2021, 21, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigusse, A.B.; Mengistie, D.A.; Malengier, B.; Tseghai, G.B.; Langenhove, L.V. Wearable smart textiles for long-term electrocardiography monitoring—a review. Sensors 2021, 21, 4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tat, T.; Chen, G.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, J. Smart textiles for healthcare and sustainability. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 13301–13313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanoska-Dacikj, A.; Stachewicz, U. Smart textiles and wearable technologies – opportunities offered in the fight against pandemics in relation to current COVID-19 state. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2020, 59, 487–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanoska-Dacikj, A.; Oguz-Gouillart, Y.; Hossain, G.; Kaplan, M.; Sivri, Ç.; Ros-Lis, J.V.; Mikucioniene, D.; Munir, M.U.; Kizildag, N.; Unal, S.; et al. Advanced and smart textiles during and after the COVID-19 pandemic: issues, challenges, and innovations. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, A.; Hylli, M.; Kazani, I. Investigating properties of electrically conductive textiles: a review. Tekstilec 2022, 65, 194–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Li, Y.; Bick, M.; Chen, J. Smart textiles for electricity generation. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 3668–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolez, P.I. Energy harvesting materials and structures for smart textile applications: recent progress and path forward. Sensors 2021, 21, 6297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zheng, Z. Progress in textile-based triboelectric nanogenerators for smart fabrics. Nano Energy 2019, 56, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, K.; Peng, X.; Cheng, R.; Wang, Z.L. Smart textile triboelectric nanogenerators: prospective strategies for improving electricity output performance. Nanoenergy Adv. 2022, 2, 133–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, W.; Chen, P.; He, S.; Sun, X.; Peng, H. Smart electronic textiles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 6140–6169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veske, P.; Ilén, E. Review of the end-of-life solutions in electronics-based smart textiles. J. Text. Inst. 2021, 112, 1500–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoppa, M.; Chiolerio, A. Wearable electronics and smart textiles: a critical review. Sensors 2014, 14, 11957–11992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahremani Honarvar, M.; Latifi, M. Overview of wearable electronics and smart textiles. J. Text. Inst. 2017, 108, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, K.; Kumar, J.; Pandit, P. Recent advancements in wearable & smart textiles: an overview. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 16, 1518–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagott, J.; Parachuru, R. An overview of recent developments in the field of wearable smart textiles. J. Text. Sci. Eng. 2018, 08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Chen, G.; Bick, M.; Chen, J. Smart textiles for personalized thermoregulation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 9357–9374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, R. Smart Textiles for Protection; Elsevier, 2012. ISBN 978-0-85709-762-0.

- Degenstein, L.M.; Sameoto, D.; Hogan, J.D.; Asad, A.; Dolez, P.I. Smart textiles for visible and IR camouflage application: state-of-the-art and microfabrication path forward. Micromachines 2021, 12, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramlow, H.; Andrade, K.L.; Immich, A.P.S. Smart textiles: an overview of recent progress on chromic textiles. J. Text. Inst. 2021, 112, 152–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jiang, S.; Tian, M.; Su, Y.; Li, J. Mapping the research status and dynamic frontiers of functional clothing: a review via bibliometric and knowledge visualization. Int. J. Cloth. Sci. Technol. 2022, 34, 697–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de-la-Fuente-Robles, Y.-M.; Ricoy-Cano, A.-J.; Albín-Rodríguez, A.-P.; López-Ruiz, J.L.; Espinilla-Estévez, M. Past, present and future of research on wearable technologies for healthcare: a bibliometric analysis using Scopus. Sensors 2022, 22, 8599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, M.; Li, J. Knowledge mapping of protective clothing research—a bibliometric analysis based on visualization methodology. Text. Res. J. 2019, 89, 3203–3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halepoto, H.; Gong, T.; Memon, H. A Bibliometric analysis of antibacterial textiles. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataglini, W.V.; Forno, A.J.D.; Steffens, F.; Kipper, L.M. 3D printing technology: an overview of the textile industry. Proc. Int. Conf. Ind. Eng. Oper. Manag. Sao Paulo Braz. April 5 - 8 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Falagas, M.E.; Pitsouni, E.I.; Malietzis, G.A.; Pappas, G. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: strengths and weaknesses. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravšelj, D.; Umek, L.; Todorovski, L.; Aristovnik, A. A review of digital era governance research in the first two decades: a bibliometric study. Future Internet 2022, 14, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: an R-Tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. VOSviewer Manual: Manual for VOSviewer Version 1.6. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Petrovich, E. Science mapping and science maps. Knowl. Organ. 2021, 48, 535–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijssen, R.J.W. A Scientometric cognitive study of neural network research: expert mental maps versus bibliometric maps. Scientometrics 1993, 28, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschalidou, V. Bibliometric analysis on business processes: M.Sc. Thesis, Πανεπιστήμιο Μακεδονίας, 2022.

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: an overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Salcedo, M.; Martínez, M.Á.; Moral-Munoz, J.A.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Cobo, M.J. Some bibliometric procedures for analyzing and evaluating research fields. Appl. Intell. 2018, 48, 1275–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyons, E.C.M.; Moed, H.F.; Van Raan, A.F.J. Integrating research performance analysis and science mapping. Scientometrics 1999, 46, 591–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raan, A.F.J. van Handbook of Quantitative Studies of Science and Technology; Elsevier, 2013. ISBN 978-1-4832-9016-4.

- Narin, F.; Hamilton, K.S. Bibliometric performance measures. Scientometrics 1996, 36, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M.J.; López-Herrera, A.G.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F. An approach for detecting, quantifying, and visualizing the evolution of a research field: a practical application to the fuzzy sets theory field. J. Informetr. 2011, 5, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Rodríguez, A.-R.; Ruíz-Navarro, J. Changes in the intellectual structure of strategic management research: a bibliometric study of the Strategic Management Journal, 1980–2000. Strateg. Manag. J. 2004, 25, 981–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, H.K.; Kumar, S.; Pandey, N. Forty years of the Journal of Futures Markets: a bibliometric overview. J. Futur. Mark. 2021, 41, 1027–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, H. Update on science mapping: creating large document spaces. Scientometrics 1997, 38, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börner, K.; Chen, C.; Boyack, K.W. Visualizing knowledge domains. Annu. Rev. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 179–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, S.A.; Van der Veer Martens, B. Mapping research specialties. Annu. Rev. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 213–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajovic, I.; Boh Podgornik, B. Bibliometric analysis of visualizations in computer graphics: a study. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440211071104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M. j.; López-Herrera, A. g.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F. Science mapping software tools: review, analysis, and cooperative study among tools. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 62, 1382–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Goerlandt, F.; Reniers, G. An Overview of scientometric mapping for the safety science community: methods, tools, and framework. Saf. Sci. 2021, 134, 105093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M. j.; López-Herrera, A. g.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F. SciMAT: a new science mapping analysis software tool. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2012, 63, 1609–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnusdei, G.P.; Elia, V.; Gnoni, M.G. Is digital twin technology supporting safety management? a bibliometric and systematic review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujas, T.; Vladimir, N.; Koričan, M.; Vukić, M.; Ćatipović, I.; Fan, A. Extended bibliometric review of technical challenges in mariculture production and research hotspot Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.; Cobo, M.J. What is the future of work? a science mapping analysis. Eur. Manag. J. 2020, 38, 846–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Viedma, E.; López-Robles, J.-R.; Guallar, J.; Cobo, M.-J. Global trends in coronavirus research at the time of Covid-19: a general bibliometric approach and content analysis using SciMAT. Prof. Inf. 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, M.J. Interactive garment design using three-dimensional surface modelling techniques. Ph.D. Thesis, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hinds, B.K.; McCartney, J. Interactive garment design. Vis. Comput. 1990, 6, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, J. Intelligent fabrics for keeping cool. Afr. Text. 1992, 31–32. [Google Scholar]

- Stylios, G.; Sotomi, O.J.; Zhu, R.; Fan, J.; Xu, Y.M.; Deacon, R. Sewability Integrated Environment (SIE) for intelligent garment manufacture: 4th international conference on advanced factory automation 1994. 4th Int. Conf. Adv. Fact. Autom. Fact. 2000 1994, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anon Intelligent fabrics exact their price. Bekleidung/Wear 1994, 8, 25–26.

- Kambe, H.; Yamasaki, N.; Lee, M.W. Super TEX-SIM: interactive textile design and simulation. J. Vis. Comput. Animat. 1994, 5, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylios, G.; Sotomi, O.J.; Zhu, R.; Descon, R. Intelligent garment manufacture. Text. Asia 1995, 26, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Stylios, G.; Sotomi, O.J.; Zhu, R.; Xu, Y.M.; Deacon, R. The mechatronic principles for intelligent sewing environments. Mechatronics 1995, 5, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, S. Smart clothing: the shift to wearable computing. Commun. ACM 1996, 39, 23–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylios, G.; Sotomi, J.O. Thinking sewing machines for intelligent garment manufacture. Int. J. Cloth. Sci. Technol. 1996, 8, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladman Sydney, A.; Matsumoto, E.A.; Nuzzo, R.G.; Mahadevan, L.; Lewis, J.A. Biomimetic 4D printing. Nat. Mater. 2016, 15, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantelopoulos, A.; Bourbakis, N.G. A Survey on wearable sensor-based systems for health monitoring and prognosis. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part C Appl. Rev. 2010, 40, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.; Lan, X.; Liu, Y.; Du, S. Shape-memory polymers and their composites: stimulus methods and applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2011, 56, 1077–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Zou, H.; Liu, R.; Tao, C.; Fan, X.; Wang, Z.L. Micro-cable structured textile for simultaneously harvesting solar and mechanical energy. Nat. Energy 2016, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulos, M.N.K.; Wheeler, S.; Tavares, C.; Jones, R. How smartphones are changing the face of mobile and participatory healthcare: an overview, with example from ECAALYX. Biomed. Eng. Online 2011, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Xie, J.; Liu, W.; Xia, Y. Electrospun nanofibers: new concepts, materials, and applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 1976–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, S.; Mondal, T.; Deen, M.J. Wearable sensors for remote health monitoring. Sens. Switz. 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.; Estève, D.; Fourniols, J.-Y.; Escriba, C.; Campo, E. Smart wearable systems: current status and future challenges. Artif. Intell. Med. 2012, 56, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Professor Stephen Beeby, University of Southampton. Available online: https://www.southampton.ac.uk/people/5wyhkv/professor-stephen-beeby (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Dr Russel Torah. Available online: https://www.arm.ecs.soton.ac.uk/people/dr-russel-torah/ (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Paosangthong, W.; Wagih, M.; Torah, R.; Beeby, S. Textile-based triboelectric nanogenerator with alternating positive and negative freestanding woven structure for harvesting sliding energy in all directions. Nano Energy 2022, 92, 106739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Torah, R.; Nunes-Matos, H.; Wei, Y.; Beeby, S.; Tudor, J.; Yang, K. Integration and testing of a three-axis accelerometer in a woven e-textile sleeve for wearable movement monitoring. Sensors 2020, 20, 5033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komolafe, A.; Torah, R.; Wei, Y.; Nunes-Matos, H.; Li, M.; Hardy, D.; Dias, T.; Tudor, M.; Beeby, S. Integrating flexible filament circuits for e-textile applications. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2019, 4, 1900176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Meadmore, K.; Freeman, C.; Grabham, N.; Hughes, A.-M.; Wei, Y.; Torah, R.; Glanc-Gostkiewicz, M.; Beeby, S.; Tudor, J. Development of user-friendly wearable electronic textiles for healthcare applications. Sensors 2018, 18, 2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Torah, R.; Wei, Y.; Beeby, S.; Tudor, J. Waterproof and durable screen printed silver conductive tracks on textiles. Text. Res. J. 2013, 83, 2023–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, G.; Torah, R.; Beeby, S.; Tudor, J. Novel active electrodes for ECG monitoring on woven textiles fabricated by screen and stencil printing. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2015, 221, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZL Wang’s Homepage. Available online: https://nanoscience.gatech.edu/ (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Zhong Lin Wang (0000-0002-5530-0380). Available online: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5530-0380 (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Lv, T.; Cheng, R.; Wei, C.; Su, E.; Jiang, T.; Sheng, F.; Peng, X.; Dong, K.; Wang, Z.L. All-fabric direct-current triboelectric nanogenerators based on the tribovoltaic effect as power textiles. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2301178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, B.; Gao, Y.; Yuan, W.; Li, X.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Z.L.; Wang, J. A high-output silk-based triboelectric nanogenerator with durability and humidity resistance. Nano Energy 2023, 108, 108244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Luo, L.; Yang, J.; Han, J.; Liu, Y.; Jiao, H.; Wu, S.; Cheng, L.; Feng, Z.; Sun, J.; et al. Scalable spinning, winding, and knitting graphene textile TENG for energy harvesting and human motion recognition. Nano Energy 2023, 107, 108137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, C.; Wei, C.; Sheng, F.; Cheng, R.; Li, Y.; Zheng, G.; Dong, K.; Wang, Z.L. Scalable one-step wet-spinning of triboelectric fibers for large-area power and sensing textiles. Nano Res. 2023, 16, 7518–7526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Liu, S.; Lin, Z.; Zhu, S.; Ma, L.; Wang, Z.L. Industrial fabrication of 3D braided stretchable hierarchical interlocked fancy-yarn triboelectric nanogenerator for self-powered smart fitness system. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2201288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Han, J.; Shi, Z.; Chen, K.; Xu, N.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, R.; Tao, Y.; Sun, Q.; Wang, Z.L.; et al. Biodegradable, super-strong, and conductive cellulose macrofibers for fabric-based triboelectric nanogenerator. Nano-Micro Lett. 2022, 14, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, F.; Ou, Z.; Gao, X.; Chen, B.; Wang, Z.L. Harvesting electrical energy from high temperature environment by aerogel nano-covered triboelectric yarns. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2205275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, F.; Zhang, B.; Cheng, R.; Wei, C.; Shen, S.; Ning, C.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.L.; Dong, K. Wearable energy harvesting-storage hybrid textiles as on-body self-charging power systems. Nano Res. Energy 2023, 2, e9120079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Cheng, R.; Ning, C.; Wei, X.; Peng, X.; Lv, T.; Sheng, F.; Dong, K.; Wang, Z.L. A self-powered body motion sensing network integrated with multiple triboelectric fabrics for biometric gait recognition and auxiliary rehabilitation training. Adv. Funct. Mater. in press. 2303562. [CrossRef]

- Dong, K.; Peng, X.; Cheng, R.; Ning, C.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.L. Advances in high-performance autonomous energy and self-powered sensing textiles with novel 3D fabric structures. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2109355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, S.; Sun, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Lin, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, Z.L. 3D interlocked all-textile structured triboelectric pressure sensor for accurately measuring epidermal pulse waves in amphibious environments. Nano Res. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, C.; Cheng, R.; Jiang, Y.; Sheng, F.; Yi, J.; Shen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, X.; Dong, K.; Wang, Z.L. Helical fiber strain sensors based on triboelectric nanogenerators for self-powered human respiratory monitoring. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 2811–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; An, J.; Liang, F.; Zuo, G.; Yi, J.; Ning, C.; Zhang, H.; Dong, K.; Wang, Z.L. Knitted self-powered sensing textiles for machine learning-assisted sitting posture monitoring and correction. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 8389–8397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Xu, X.; Chen, S.; Fang, Y.; Shi, X.; Deng, Y.; Wang, Z.-L.; Cao, C. Skin-inspired textile-based tactile sensors enable multifunctional sensing of wearables and soft robots. Nano Energy 2022, 96, 107137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Yi, J.; Cheng, R.; Ma, L.; Sheng, F.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ning, C.; Wang, H.; Dong, K.; et al. Electromagnetic shielding triboelectric yarns for human–machine interacting. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2022, 8, 2101130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bie, B.; Xu, W.; Lv, Y. Liquid metal-based textiles for smart clothes. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2023, 66, 1511–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Leber, A.; Das Gupta, T.; Chandran, R.; Volpi, M.; Qu, Y.; Nguyen-Dang, T.; Bartolomei, N.; Yan, W.; Sorin, F. High-efficiency super-elastic liquid metal based triboelectric fibers and textiles. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Zhu, M.; Wu, B.; Li, Z.; Sun, S.; Wu, P. Conductance-stable liquid metal sheath-core microfibers for stretchy smart fabrics and self-powered Sensing. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabg4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Votzke, C.; Daalkhaijav, U.; Mengüç, Y.; Johnston, M.L. 3D-printed liquid metal interconnects for stretchable electronics. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 19, 3832–3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Sharma, S.; Adak, B.; Hossain, M.M.; LaChance, A.M.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Sun, L. Two-dimensional MXenes: new frontier of wearable and flexible electronics. InfoMat 2022, 4, e12295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Ma, K.; Yang, B.; Li, H.; Tao, X. Textile electronics for VR/AR applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2007254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Fu, X.; He, J.; Shi, X.; Chen, T.; Chen, P.; Wang, B.; Peng, H. Application challenges in fiber and textile electronics. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1901971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newby, S.; Mirihanage, W.; Fernando, A. Recent advancements in thermoelectric generators for smart textile application. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33, 104585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Dai, X.; Sun, Z.; Zhu, S.; Xiong, L.; Liang, Q.; Wong, M.-C.; Huang, L.-B.; Qin, Q.; Hao, J. Highly integrated, scalable manufacturing and stretchable conductive core/shell fibers for strain sensing and self-powered smart textiles. Nano Energy 2022, 98, 107240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Yang, J.; Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Wei, W.; Liu, J.; Chen, J.; Yang, J. Large-scale and washable smart textiles based on triboelectric nanogenerator arrays for self-powered sleeping monitoring. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1704112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Xiao, X.; Yin, J.; Xiao, X.; Chen, J. Self-powered smart gloves based on triboelectric nanogenerators. Small Methods 2022, 6, 2200830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Dhangar, M.; Paul, S.; Chaturvedi, K.; Khan, M.A.; Srivastava, A.K. Recent advances for fabricating smart electromagnetic interference shielding textile: a comprehensive review. Electron. Mater. Lett. 2022, 18, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Zhou, B.; Zheng, Q.; Wang, L.; Jiang, W.; Snyder, G.J. Stretchable fabric generates electric power from woven thermoelectric fibers. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Padgett, S.; Cai, Z.; Conta, G.; Wu, Y.; He, Q.; Zhang, S.; Sun, C.; Liu, J.; Fan, E.; et al. Single-layered ultra-soft washable smart textiles for all-around ballistocardiograph, respiration, and posture monitoring during sleep. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 155, 112064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; He, T.; Zhu, M.; Sun, Z.; Shi, Q.; Zhu, J.; Dong, B.; Yuce, M.R.; Lee, C. Deep learning-enabled triboelectric smart socks for IoT-based gait analysis and VR applications. Npj Flex. Electron. 2020, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Chen, K.; Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Meng, K.; Sun, C.; He, Q.; Fan, W.; et al. Sign-to-speech translation using machine-learning-assisted stretchable sensor arrays. Nat. Electron. 2020, 3, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, G.; Fang, Y.; Tat, T.; Xiao, X.; Song, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, J. Soft fibers with magnetoelasticity for wearable electronics. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Noel, G.; Loke, G.; Meiklejohn, E.; Khudiyev, T.; Marion, J.; Rui, G.; Lin, J.; Cherston, J.; Sahasrabudhe, A.; et al. Single fibre enables acoustic fabrics via nanometre-scale vibrations. Nature 2022, 603, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Kim, K.N.; Lv, J.; Tehrani, F.; Lin, M.; Lin, Z.; Moon, J.-M.; Ma, J.; Yu, J.; Xu, S.; et al. A self-sustainable wearable multi-modular e-textile bioenergy microgrid system. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syafiuddin, A. Toward a comprehensive understanding of textiles functionalized with silver nanoparticles. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2019, 66, 793–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štular, D.; Jerman, I.; Naglič, I.; Simončič, B.; Tomšič, B. Embedment of silver into temperature- and PH-responsive microgel for the development of smart textiles with simultaneous moisture management and controlled antimicrobial activities. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 159, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Subhani, K.; Rasheed, A.; Ashraf, M.; Afzal, A.; Ramzan, B.; Sarwar, Z. Development of conductive fabrics by using silver nanoparticles for electronic applications. J. Electron. Mater. 2020, 49, 1330–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasundaram, S.; Rahaman, A.; Kim, B. Direct preparation of β-crystalline poly(vinylidene fluoride) nanofibers by electrospinning and the use of non-polar silver nanoparticles coated poly(vinylidene fluoride) nanofibers as electrodes for piezoelectric sensor. Polymer 2019, 183, 121910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayan, S.; Pal, S.; Ray, S.K. Interface engineered silver nanoparticles decorated G-C3N4 nanosheets for textile based triboelectric nanogenerators as wearable power sources. Nano Energy 2022, 94, 106928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Miao, J.; Fan, Q.; Zhang, W.; Zuo, X.; Tian, M.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, X.; Qu, L. Recent progress on smart fiber and textile based wearable strain sensors: materials, fabrications and applications. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2022, 4, 361–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Jin, X.; Lan, C.; Guo, Z.H.; Zhou, R.; Sun, H.; Shao, Y.; Meng, J.; Liu, Y.; Pu, X. 3D arch-structured and machine-knitted triboelectric fabrics as self-powered strain sensors of smart textiles. Nano Energy 2023, 109, 108312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, L.; Guo, Z.H.; Zhang, P.; Wan, J.; Pu, X.; Wang, Z.L. Stretchable, self-healing, conductive hydrogel fibers for strain sensing and triboelectric energy-harvesting smart textiles. Nano Energy 2020, 78, 105389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazani, I.; Hylli, M.; Berberi, P. Electrical resistivity of conductive leather and influence of air temperature and humidity. Tekstilec 2021, 64, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xia, X.; Ma, K.; Xia, G.; Wu, M.; Cheung, Y.H.; Yu, H.; Zou, B.; Zhang, X.; Farha, O.K.; et al. Functional textiles with smart properties: their fabrications and sustainable applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, n/a, 2301607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Wu, J.; Yan, J.; Liu, X. Advanced fiber materials for wearable electronics. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2023, 5, 12–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.D.; Li, N.; Jung de Andrade, M.; Fang, S.; Oh, J.; Spinks, G.M.; Kozlov, M.E.; Haines, C.S.; Suh, D.; Foroughi, J.; et al. Electrically, chemically, and photonically powered torsional and tensile actuation of hybrid carbon nanotube yarn muscles. Science 2012, 338, 928–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Jung de Andrade, M.; Fang, S.; Wang, X.; Gao, E.; Li, N.; Kim, S.H.; Wang, H.; Hou, C.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Sheath-run artificial muscles. Science 2019, 365, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, N.; Peng, Y.; Sun, F.; Hu, J. High-performance fasciated yarn artificial muscles prepared by hierarchical structuring and sheath–core coupling for versatile textile actuators. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2023, 5, 1534–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, P.T.; Welch, D.; Spiggle, J.; Thai, M.T.; Hoang, T.T.; Davies, J.; Nguyen, C.C.; Zhu, K.; Phan, H.-P.; Lovell, N.H.; et al. Fabrication, nonlinear modeling, and control of woven hydraulic artificial muscles for wearable applications. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2023, 360, 114555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Z.; Liu, Z.; Hou, Y.; Jiang, H.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, X. The rising aerogel fibers: status, challenges, and opportunities. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2205762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alterby, M.; Johnson, E.; Jonason, A.; Svensson, D. 3D Printing Hydrogel Artificial Muscles and Microrobotics: Student Thesis; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, S.; Zhang, X.; Naficy, S.; Salahuddin, B.; Jager, E.W.H.; Zhu, Z. Plant-like tropisms in artificial muscles. Adv. Mater. 2023, n/a, 2212046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faruk, M.O.; Ahmed, A.; Jalil, M.A.; Islam, M.T.; Shamim, A.M.; Adak, B.; Hossain, M.M.; Mukhopadhyay, S. Functional textiles and composite based wearable thermal devices for joule heating: progress and perspectives. Appl. Mater. Today 2021, 23, 101025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Lei, Z.; Wang, L.; Tian, M.; Zhu, S.; Xiao, H.; Tang, X.; Qu, L. Flexible MXene-decorated fabric with interwoven conductive networks for integrated Joule heating, electromagnetic interference shielding, and strain sensing performances. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 14459–14467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Jalil, M.A.; Hossain, M.M.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Adak, B.; Islam, M.T.; Parvez, M.S.; Mukhopadhyay, S. A PEDOT:PSS and graphene-clad smart textile-based wearable electronic Joule heater with high thermal stability. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 16204–16215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, R.; Ye, D.; Cai, G.; Yang, H.; Gu, S.; Xu, W. Multi-functional and water-resistant conductive silver nanoparticle-decorated cotton textiles with excellent Joule heating performances and human motion monitoring. Cellulose 2021, 28, 7483–7495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanivada, U.K.; Esteves, D.; Arruda, L.M.; Silva, C.A.; Moreira, I.P.; Fangueiro, R. Joule-heating effect of thin films with carbon-based nanomaterials. Materials 2022, 15, 4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalil, M.A.; Ahmed, A.; Hossain, M.M.; Adak, B.; Islam, M.T.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Parvez, M.S.; Shkir, Mohd. ; Mukhopadhyay, S. Synthesis of PEDOT:PSS solution-processed electronic textiles for enhanced Joule heating. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 12716–12723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Li, X.; Sun, B.; Huang, X.-L.; Ning, X.; Long, Y.-Z.; Zheng, J. Flexible MXene decorative nonwovens with patterned structures for integrated Joule heating and strain sensing. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2023, 358, 114426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owyeung, R.E.; Panzer, M.J.; Sonkusale, S.R. Colorimetric gas sensing washable threads for smart textiles. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busolo, T.; Szewczyk, P.K.; Nair, M.; Stachewicz, U.; Kar-Narayan, S. Triboelectric yarns with electrospun functional polymer coatings for highly durable and washable smart textile applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 16876–16886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munirathinam, P.; Anna Mathew, A.; Shanmugasundaram, V.; Vivekananthan, V.; Purusothaman, Y.; Kim, S.-J.; Chandrasekhar, A. A comprehensive review on triboelectric nanogenerators based on real-time applications in energy harvesting and self-powered sensing. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2023, 297, 116762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cai, J.; Yu, J.; Li, Z.; Ding, B. The rising of fiber constructed piezo/triboelectric nanogenerators: from material selections, fabrication techniques to emerging applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. n/a 2303249. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, N.; Chakrabarti, S.; Jones, L.D.; Ashili, S. Smart wearables addressing gait disorders: a review. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35, 106250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drăgulinescu, A.; Drăgulinescu, A.-M.; Zincă, G.; Bucur, D.; Feieș, V.; Neagu, D.-M. Smart socks and in-shoe systems: state-of-the-art for two popular technologies for foot motion analysis, sports, and medical applications. Sensors 2020, 20, 4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amitrano, F.; Coccia, A.; Ricciardi, C.; Donisi, L.; Cesarelli, G.; Capodaglio, E.M.; D’Addio, G. Design and validation of an e-textile-based wearable sock for remote gait and postural assessment. Sensors 2020, 20, 6691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mileti, I.; Pasinetti, S.; Taborri, J.; Patanè, F.; Lancini, M.; Rossi, S. Realization and Validation of a Piezoresistive Textile-Based Insole for Gait-Related Measurements. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference (I2MTC); May 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zahn, E.F.; Fischer, H.F.; Gleiß, C.E.; Avramidis, E.; Joost, G. Textile Game Controller: Smart Knee Pads for Therapeutic Exercising. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, April 19, 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Xu, H.; Zhong, W.; Ming, X.; Li, M.; Hu, X.; Jia, K.; Wang, D. Robust and breathable all-textile gait analysis platform based on lenet convolutional neural networks and embroidery technique. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2023, 360, 114549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Botero, L.; Agrawala, A.; Kramer-Bottiglio, R. Stretchable, breathable, and washable fabric sensor for human motion monitoring. Adv. Mater. Technol. n/a 2300378. [CrossRef]

- Pazar, A.; Khalilbayli, F.; Ozlem, K.; Yilmaz, A.F.; Atalay, A.T.; Atalay, O.; İnce, G. Gait Phase Recognition Using Textile-Based Sensor. In Proceedings of the 2022 7th International Conference on Computer Science and Engineering (UBMK); September 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno, M.; De Nunzio, A.M.; Quartarone, A.; Militi, A.; Petralito, F.; Calabrò, R.S. Gait analysis in neurorehabilitation: from research to clinical practice. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, T.; Zhao, M. The application of smart fibers and smart textiles. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1790, 012084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakdel, E.; Wang, J.; Kashi, S.; Sun, L.; Wang, X. Advances in photocatalytic self-cleaning, superhydrophobic and electromagnetic interference shielding textile treatments. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 277, 102116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, Z.; Qi, S.; Shuaib, S.S.A.; Yuan, W. Flexible, stimuli-responsive and self-cleaning phase change fiber for thermal energy storage and smart textiles. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 228, 109431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.A.; Javed, K.; Fraz, A.; Anwar, F. Recent Trends in wearable electronic textiles (e-textiles): a mini review. J. Des. Text. 2023, 2, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, C.C.; Kim, J. Highly elastic capacitive pressure sensor based on smart textiles for full-range human motion monitoring. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2020, 314, 112029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seesaard, T.; Wongchoosuk, C. Fabric-based piezoresistive Ti3AlC2/PEDOT:PSS force sensor for wearable e-textile applications. Org. Electron. 2023, 122, 106894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samartzis, N.; Athanasiou, M.; Sygellou, L.; Yannopoulos, S.N. Modified Laser-Assisted Method for Direct Graphene Deposition on Sensitive Flexible Substrates: Fabrication of Interdigitated Micro-Flexible Supercapacitors. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4522623. [CrossRef]

- Mersch, J.; Witham, N.S.; Solzbacher, F.; Gerlach, G. Continuous textile manufacturing method for twisted coiled polymer artificial muscles. Text. Res. J. 2023, 00405175231181095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Xiang, Z.; OuYang, X.; Zhang, J.; Lau, N.; Zhou, J.; Chan, C.C. Wearable fiber optic technology based on smart textile: a review. Materials 2019, 12, 3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Xia, Z.; Hurren, C.; Nilghaz, A.; Wang, X. Textiles in soft robots: current progress and future trends. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 196, 113690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Chen, J.; Lee, P.S. Functional fibers and fabrics for soft robotics, wearables, and human–robot interface. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2002640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, C.; Yang, X.; Chen, W. Flexible actuators for soft robotics. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2020, 2, 1900077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin, J.A. Bibliometric methods: pitfalls and possibilities. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2005, 97, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafols, I.; Porter, A.L.; Leydesdorff, L. Science overlay maps: a new tool for research policy and library management. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2010, 61, 1871–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-W.; Huang, M.-H.; Lin, C.-W. Evolution of research subjects in library and information science based on keyword, bibliographical coupling, and co-citation analyses. Scientometrics 2015, 105, 2071–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bibliometric items | Findings |

|---|---|

| Timespan | 1989–2022 |

| Sources (journals, proceedings, etc.) | 1,739 |

| Documents | 5,810 |

| Annual growth rate % | 22.36 |

| Average citations per document | 22 |

| References | 166,487 |

| DOCUMENT CONTENTS | |

| Keywords Plus (ID) | 23,347 |

| Authors' Keywords (DE) | 10,502 |

| AUTHORS | |

| Authors | 12,314 |

| Authors of single-authored documents | 538 |

| AUTHORS COLLABORATION | |

| Single-authored documents | 683 |

| Co-authors per document | 4.33 |

| International co-authorships % | 18.24 |

| DOCUMENT TYPES | |

| Articles | 3,560 |

| Conference papers | 1,879 |

| Reviews | 371 |

| Rank | Document | Total citations | Ref. no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gladman Sydney, A., Matsumoto, E. A., Nuzzo, R. G., Mahadevan, L., & Lewis, J. A. (2016). Biomimetic 4D printing. Nature Materials, 15(4), 413-418. doi:10.1038/nmat4544 | 1.982 | [94] |

| 2 | Pantelopoulos, A., & Bourbakis, N. G. (2010). A survey on wearable sensor-based systems for health monitoring and prognosis. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man and Cybernetics Part C: Applications and Reviews, 40(1), 1-12. doi:10.1109/TSMCC.2009.2032660 | 1.715 | [95] |

| 3 | Stoppa, M., & Chiolerio, A. (2014). Wearable electronics and smart textiles: A critical review. Sensors (Switzerland), 14(7), 11957-11992. doi:10.3390/s140711957 | 1.454 | [45] |

| 4 | Leng, J., Lan, X., Liu, Y., & Du, S. (2011). Shape-memory polymers and their composites: Stimulus methods and applications. Progress in Materials Science, 56(7), 1077-1135. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2011.03.001 | 1.239 | [96] |

| 5 | Mondal, S. (2008). Phase change materials for smart textiles - an overview. Applied Thermal Engineering, 28(11-12), 1536-1550. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2007.08.009 | 935 | [28] |

| 6 | Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Zou, H.; Liu, R.; Tao, C.; Fan, X.; Wang, Z.L. (2016). Micro-cable structured textile for simultaneously harvesting solar and mechanical energy. Nature Energy, 1(10) doi:10.1038/nenergy.2016.138 | 786 | [97] |

| 7 | Boulos, M. N. K., Wheeler, S., Tavares, C., & Jones, R. (2011). How smartphones are changing the face of mobile and participatory healthcare: An overview, with example from eCAALYX. BioMedical Engineering Online, 10 doi:10.1186/1475-925X-10-24 | 767 | [98] |

| 8 | Xue, J., Xie, J., Liu, W., & Xia, Y. (2017). Electrospun nanofibers: New concepts, materials, and applications. Accounts of Chemical Research, 50(8), 1976-1987. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00218 | 716 | [99] |

| 9 | Majumder, S., Mondal, T., & Deen, M. J. (2017). Wearable sensors for remote health monitoring. Sensors (Switzerland), 17(1) doi:10.3390/s17010130 | 687 | [100] |

| 10 | Chan, M., Estève, D., Fourniols, J.-Y., Escriba, C., & Campo, E. (2012). Smart wearable systems: Current status and future challenges. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine, 56(3), 137-156. doi:10.1016/j.artmed.2012.09.003 | 664 | [101] |

| Author | Institution | Number of documents | Number of citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beeby, Stephen P. | University of Southampton, UK | 61 | 1,300 |

| Torah, Russel N. | University of Southampton, UK | 58 | 1,023 |

| Tudor, M. John | University of Southampton, UK | 45 | 895 |

| Koncar, Vladan | ENSAIT Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Arts et Industries Textiles, Roubaix, France | 43 | 1,151 |

| van Langenhove, Lieva | Universiteit Gent, Belgium | 42 | 1,757 |

| Tröster, Gerhard | ETH Zürich, Switzerland | 32 | 1,185 |

| Tao, Xiaoming | Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong | 30 | 1,036 |

| Yang, Kai | University of Southampton, UK | 30 | 709 |

| Wang, Zhong Lin | Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China | 29 | 6,556 |

| Dunne, Lucy E. | University of Minnesota Twin Cities, Minneapolis, USA | 28 | 371 |

| Rank | Source | Number ofdocuments | Rank | Source | Number of citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sensors | 139 | 1 | Advanced Materials | 6,488 |

| 2 | ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces | 132 | 2 | ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces | 5,985 |

| 3 | Textile Research Journal | 121 | 3 | Sensors | 5,323 |

| 4 | Proceedings – International Symposium on Wearable Computers, ISWC* | 70 | 4 | ACS Nano | 5,055 |

| 5 | Proceedings of SPIE – The International Society for Optical Engineering* | 67 | 5 | Advanced Functional Materials | 4,495 |

| 6 | IEEE Sensors Journal | 66 | 6 | Nano Energy | 2,521 |

| 7 | Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – Proceedings* | 62 | 7 | Textile Research Journal | 2,298 |

| 8 | ACM International Conference Proceeding Series* | 60 | 8 | Sensors and Actuators, A: Physical | 2,043 |

| 9 | Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics)* | 59 | 9 | Smart Materials and Structures | 1,997 |

| 10 | Journal of The Textile Institute | 56 | 10 | IEEE Sensors Journal | 1,877 |

| Authors’ keywords | Average publication year | Occurrence |

|---|---|---|

| liquid metal | 2021.45 | 11 |

| MXenes | 2020.94 | 33 |

| textile electronics | 2020.92 | 13 |

| self-powered | 2020.83 | 12 |

| EMI shielding | 2020.64 | 22 |

| self-powered sensors | 2020.53 | 15 |

| silver nanoparticles | 2020.47 | 15 |

| strain sensing | 2020.40 | 10 |

| sustainability | 2020.39 | 18 |

| artificial muscles | 2020.22 | 23 |

| joule heating | 2020.18 | 11 |

| washable | 2020.18 | 11 |

| thermoelectrics | 2020.18 | 11 |

| triboelectric nanogenerators | 2020.16 | 63 |

| gait analysis | 2020.07 | 14 |

| self-cleaning | 2020.06 | 17 |

| fabrication | 2020.00 | 16 |

| soft robotics | 2020.00 | 13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).