1. Introduction

A large body of theoretical and empirical environmental research demonstrates that exposure to ambient air pollutants such as particulate matter (PM) and gaseous pollutants (e.g., CO, SOx, NOx, and O3) is directly linked to adverse health outcomes (e.g., asthma, bronchitis, cardiovascular conditions) (Farina et al., 2011; Kelly & Fussell, 2012; Aztatzi-Aguilar et al., 2018; Xue et al., 2019). As a developing country, Kazakhstan is currently experiencing rapid economic development, increased exploitation of resources, population growth, and intensive urbanization. As a result, air pollution is a major public health concern. Respiratory diseases account for 43.5% of the population’s morbidity (Abakhanov, 2020). Moreover, in Kazakhstan, exposure to PM is linked to 2,800 premature deaths each year (Kerimray et al., 2018).

Astana is the capital city of Kazakhstan and is characterized by extremely harsh climate conditions with long and cold winters, leading to a half-year heating period. A high concentration of air pollutants, such as PM2.5, is particularly present during the heating period. For example, the concentration of PM2.5 during wintertime ranges between 100-200 µg/m3 on several days (Assanov et al., 2021). Astana also has the second-highest number of private transportation units in the country (about 300,000) (Assanov et al., 2021).

The most recent environmental legislation has been effective in Kazakhstan since December 2019, introducing 75 new amendments. The implementation of new regulations, however, failed to improve environmental quality, establish permissible concentrations of pollutants, and preserve ecological systems and biodiversity (Abakhanov, 2020). Moreover, the majority of environmental studies conducted in Kazakhstan focus on estimating the level of ambient air pollutants and related environmental effects. However, the social aspect of air pollution-related topics is usually neglected. In Kazakhstan, the level of knowledge and awareness among the general public about air pollution may remain considerably low.

The sociological aspect of air pollution research (e.g., attitude, behavior intentions, anxiety related to air quality) is a component that can increase public involvement in mitigating risks associated with air pollution and may determine the success of potential public interventions. The majority of the sociological studies in this domain investigate the association of demographic characteristics and perception, attitude, and knowledge of air pollution (Wang et al., 2015; Qian et al., 2016; Odonkor et al., 2020). Other studies focus on the perceived air pollution risks in urban environments (e.g., levels and sources of air pollution, and related health effects) (Saksena, 2012; Maione et al., 2021), individual intervention strategies to reduce the exposure to ambient air pollutants (Laumbach et al., 2015; Janjua et al., 2021), information channels about air pollution-related topics, and pro-environmental behavior and challenges in behavior change (Carducci et al., 2017; Ramírez et al., 2019).

The theory of planned behavior explains the complex nature of individual behavior, suggesting that it is dictated by behavioral intentions that are also influenced by internal factors such as personal attitudes, perceptions, and subjective norms in a particular situation. Essentially, a strong intention to engage in a certain behavior reinforces this behavior. Individual behavior also depends on the degree of perceived behavior control (Ajzen, 1991). The theory of planned behavior was adopted in the context of environmental behavioral intentions.

Environmental behavior is suggested to be greatly influenced by perceived risks that shape individual behavior intentions. In other words, individual motivation for the behavior change is highly correlated with a negative outcome (e.g., adverse health effects) and with the perceived probability of that outcome (Keller et al., 2012; Li & Hu, 2018; Saari et al., 2021). Another crucial component of favorable environmental behavior is environmental knowledge. The research suggests that environmental consciousness is defined by perceived knowledge of what an individual can or cannot do (Hungerford & Volk, 1990, Keller et al., 2012; Li & Hu, 2018; Saari et al., 2021). That is especially important in the context of willingness to pay (WTP), which is largely influenced by the knowledge of the related topic (Vassanadumrongdee & Matsuoka, 2005). Moreover, recent studies show that the awareness of the general public about air pollution can be built through knowledge-increasing tools (i.e., media and online resources that publish information on air pollution topics) (Rajper et al., 2018; Li & Hu, 2018; Ramírez et al., 2019).

Based on the literature reviewed, the following hypotheses were set for the present study:

Environmental attitude affects the perception of national air pollution and the economy,

Institutional knowledge affects the perception of national air pollution and the economy,

Knowledge of local air quality affects the perception of national air pollution and the economy, and;

WTP affects environmental attitude.

The present study aims (1) to assess the level of knowledge of air pollution and its health effects among adult urban residents in the capital city of an emerging economy (Astana, Kazakhstan; an area of very high air pollution according to the Air Pollution Index (API)), (2) to evaluate the public perception of air pollution in the city, (3) to assess the attitude of the studied population towards environmental protection, and; (4) to estimate the relationship between knowledge, attitude, and perception using structural equation modeling (SEM) approach. The present study examines the ability of the general public to access, understand, and apply information about air pollution in a highly polluted area with a developing economy. Moreover, it carries implications for public health interventions, policy enhancement, public engagement, and international cooperation. The present study will also enable to assess the pollution-related health risks, address knowledge gaps, and promote sustainable practices, shaping individual behavior intentions, attitudes, and perceptions of local air quality.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The present work is a cross-sectional study among the urban adult population of Astana, Kazakhstan. The city’s population was estimated at 1,239,744 people at the start of 2022, with 594,742 male and 645,002 female residents, respectively. The average age of Astana residents was 30.1 years in 2021. At the beginning of 2022, 795,969 adults (≥20 years) were registered in Astana (National Bureau of Statistics, 2022).

The population of Astana has experienced continuous and rapid growth since 2001 e.g., an 11.2% increase in 2021 compared to 2020 (National Bureau of Statistics, 2022). With the increasing population, the transportation load proportionally rises and according to Assanov et al. (2021), the estimated number of private vehicles per 100 people is 26. Heavy traffic from public and private transport contributes to the degradation of air quality and exposes the population to various air pollutants (e.g., PM, NOx). Perhaps more importantly, the residents of Astana are exposed to air emissions from two coal-powered combined heating and power plants (CHPPs) as well as from residential heating, which intensifies during winter extreme cold weather episodes (Kerimray et al., 2018, Assanov et al., 2021).

2.2. Instrumentation

The framework of the survey instrument was adapted from Chin et al. (2019). The 32-item questionnaire was created via an online research software, Qualtrics (Qualtrics LLC, UT, US), in the form of a self-administered questionnaire. Snowballing sampling technique has been used. The online questionnaire was designed in three languages: English, Kazakh, and Russian, to guarantee that respondents could comfortably respond to questions in their preferred language. A sample of the survey in English is provided in

Appendix A.

The survey questionnaire was divided into three sections. The first part contained seven questions on the sociodemographic parameters of the studied population (age, gender, education, employment status, work environment, average household income, and chronic health conditions). The second part contained three questions to assess the awareness of the studied population about air pollution. This section had three multiple-choice questions to understand the perception of the general public on air quality in the region, knowledge about potential sources of air pollution, and the sources of information regarding air pollution-related topics. The second part also contained six true/false questions further evaluating participants’ knowledge of air pollution monitoring systems, sources of gaseous pollutants, air pollution-related indicators (e.g., API), and health effects related to air pollution. The third part evaluated the participants’ attitudes toward environmental protection and was composed of sixteen statements on a 5-point Likert scale. Statements covered the attitude of the studied population toward economic cost and governmental pollution management prices as well as WTP for environmental protection.

2.3. Data Collection

The survey responses were collected during May and June of 2022. Two rounds of pre-testing with 20 respondents were conducted to ascertain the correct and rational interpretation of the survey questions. The link to the anonymous survey was distributed through social media platforms and the university’s mail services. A total of 870 responses were collected. Incomplete, “straight-line”, and inconsistent survey responses were excluded from further analysis, leading to a total of 782 responses being included in the final analysis. The present research received prior approval from the International Research Ethics Committee of Nazarbayev University (NU IREC).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

With regards to the assessment of knowledge of potential sources of air pollution in

Section 2a of the questionnaire, each correct answer was given 1 point, leading to a total of 8 maximum points. In

Section 2b, 1 point was given for a correct answer, -0.2 for an incorrect response, and 0 points when answered ‘I don’t know’ (leading to a total of 6 points). In

Section 3 of the questionnaire, a higher score on a 5-point Likert scale indicated more positive attitudes in Statements 17, 19, 21, 25, 27, 28, 29, 31, and 32; whereas statements 20, 22, 23, 26, and 30 were scored in reverse i.e., a higher score indicating a negative attitude toward environmental protection.

Four statements (#17, 23, 26, and 30) represent the affective component of the attitude scale whereas five statements (#18, 25, 27, 28, and 32) denote the cognitive element. The conative component of the attitude scale is reflected in the five statements related to WTP for environmental protection (statements #19, 21, 24, 29, and 31).

The statistical analyses including descriptive analysis, t-tests, and chi-square association tests have been conducted via Stata 14.2 by StataCorp. 2015 (TX, US) to assess the relationships between knowledge about air pollution, concerns about air quality, attitudes towards environmental protection, and demographic characteristics.

2.5. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) and Model Validity

The SEM tool was used to evaluate the proposed model’s reliability and validity and to test the hypotheses set. SEM allows multivariate analysis of the relationships between the variables (Hair et al., 2018).

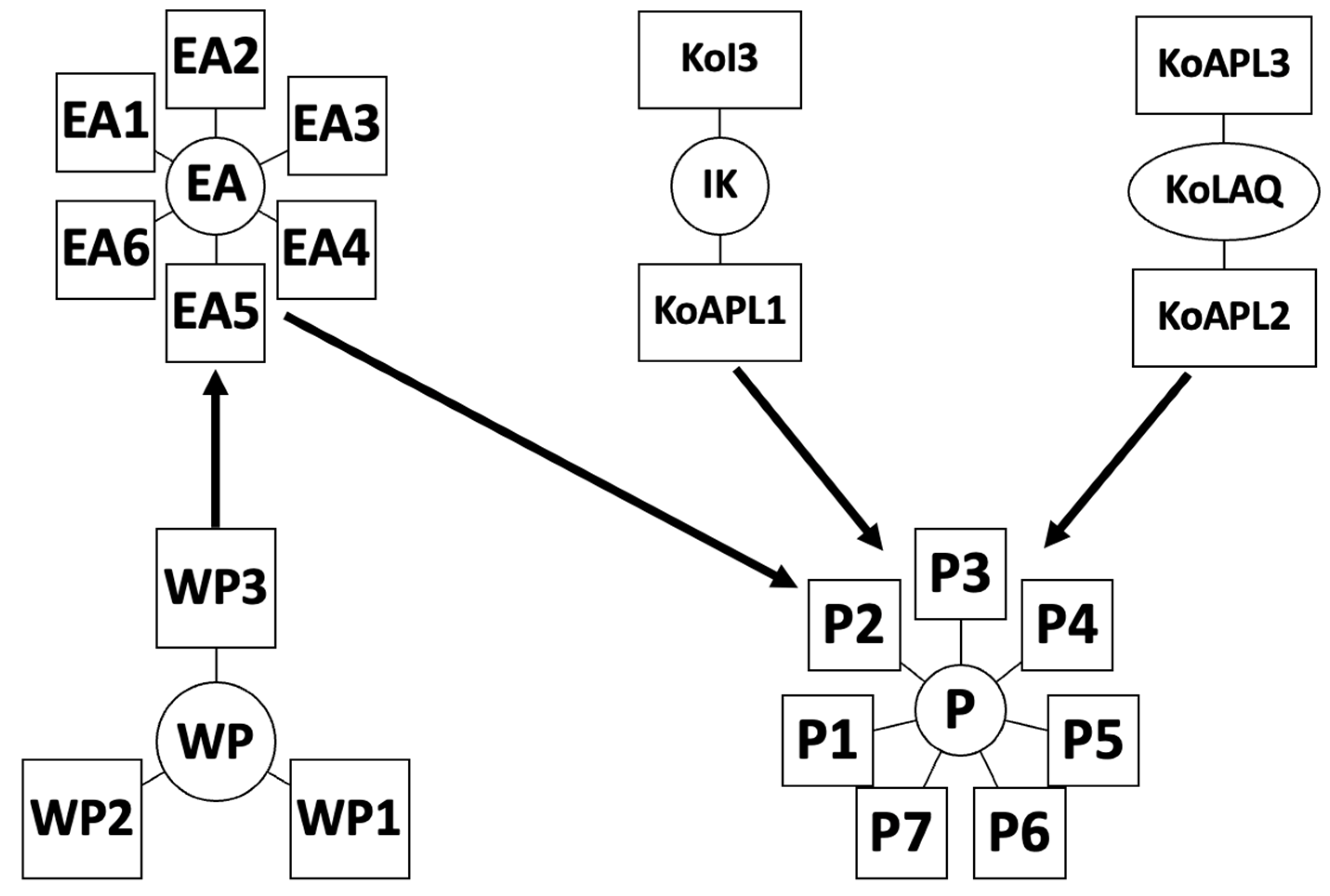

Table 1 and

Figure 1 represent the SEM’s latent, observable variables, related questions, and the model itself. First, the partial-least squares technique was used to identify the path loadings. Each latent variable was described through a minimum of two observable variables. Then, to check the hypothesis, bootstrapping was used to derive heterotrait-heteromethod correlation statistics, thus, calculating the standard error, which helps to identify the bootstrap confidence interval (95% limit). The model validity was then checked through statistical values such as outer loadings, Cronbach’s Alpha, average variance extracted, Dillon-Goldstein’s rho, and composite reliability. The acceptance criteria were the following: outer loadings > 0.7, Cronbach’s Alpha > 0.7, Average variance extracted > 0.5, Dillon-Goldstein’s rho (rho_A) > 0.7, and composite reliability > 0.7.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Studied Population

The general demographic characteristics of the participants (

Table 2) show that out of the total 782 respondents, 46.7% (n=365) were male, and 43.1% (n=425) were female. The most prevalent age group of the participants was 25–34 years old (29.2%, n=228). Half of the respondents had at least a bachelor’s degree (49.9%, n=390). More than a third of the study population (41.7%, n=326) identified as unemployed, while 30.3% (n=237) were self-employed. The majority (54.0%, n=422) of the participants described the environment they spend most of their time in as an environment where air quality is not a concern whereas 10.1% (n=79) and 11.0% (n=86) of the studied population were engaged in industrial and urban sectors, respectively. One-third of the respondents (36.1%, n=282) had an average monthly household income of less than 100,000 KZT, while 37.2% (n=291) of the participants reached the average wage of the Kazakhstani population (263,905 KZT in 2022) (Bureau of National Statistics, 2022).

3.2. SEM Validity Check

The hypothetical model was first subjected to a validity check using partial least squares analysis, after which the hypotheses set could be confirmed/rejected via bootstrapping. Starting with a convergent validity check (

Table 3) and outer loadings checks, most values exceed the acceptable limit of 0.7 including WP2 whereas several others were smaller than that value (P5, P3, P7, and KoAPI1). This states that KoAPI1 is weak in representing the “Knowledge” construct. Values for P5, P3, and P7 were within the acceptable limits (between 0.4 and 0.7) and their removal does not increase composite reliability (Hair et al., 2018). The values at the lower range could be attributed to the question wording and to the understanding of the respondents which may be subjective.

Table 4 represents the reliability and validity checks of the constructs. The institutional knowledge construct is the least reliable (Cronbach’s alpha, Dillon-Goldstein’s rho, and composite reliability are lower than the acceptable limit), which may be attributed to the limited number of questions.

Table 5 demonstrates the values for discriminant validity which indicates the differences between the constructs. All the values are distinct and discriminant.

Table 6 represents the hypothesis test check using bootstrapping, showing that all four hypotheses are supported.

Table 7 shows that the effect of Knowledge of local air quality on the perception of national air pollution and the economy is the strongest (i.e., with the largest path value: 0.626). The effects of Institutional knowledge on the Perception of national air pollution and economy and WTP on Environmental attitude are also strong (0.492 and 0.533, respectively). Interestingly, the effect of Environmental attitude on the perception of national air pollution and the economy is minimal.

3.3. Relationship Between Air Quality Perception and Sociodemographics

The public perception of air quality in Astana was affected by participants’ age, gender, education, employment status, the environment in which the respondent spent most of their time, average monthly household income (p<.001), and health status (HBP (p<.001) and COPD (p=0.005)) (

Table A1,

Appendix B).

Almost half of the respondents (42.1%, n=329) classified the air quality as moderately polluted and causing no harm. Among the respondents in the 35–44 age category, half (52.7%, n=97) considered the air quality in Astana moderately polluted, causing no detrimental effect to the general population. However, one-third of the respondents in the 45–54 and 55–64 age groups (34.3% (n=50), and 30.3% (n=23), respectively) classified the air quality as highly polluted.

Half of the female population (50.7%, n=210) described the region as moderately polluted with no significant effect, while one-third (32.6%, n=119) of male respondents shared a similar perception. Respondents with graduate degrees and full-time employment were more likely to consider the air quality level as moderately dangerous to human health (55.7%, n=44; 49.5%, n=52, respectively). The majority (69.6%, n=55) of participants working in an industrial environment noted a high level of air pollution.

3.4. Respondents’ Knowledge of Air Pollution-Related Topics

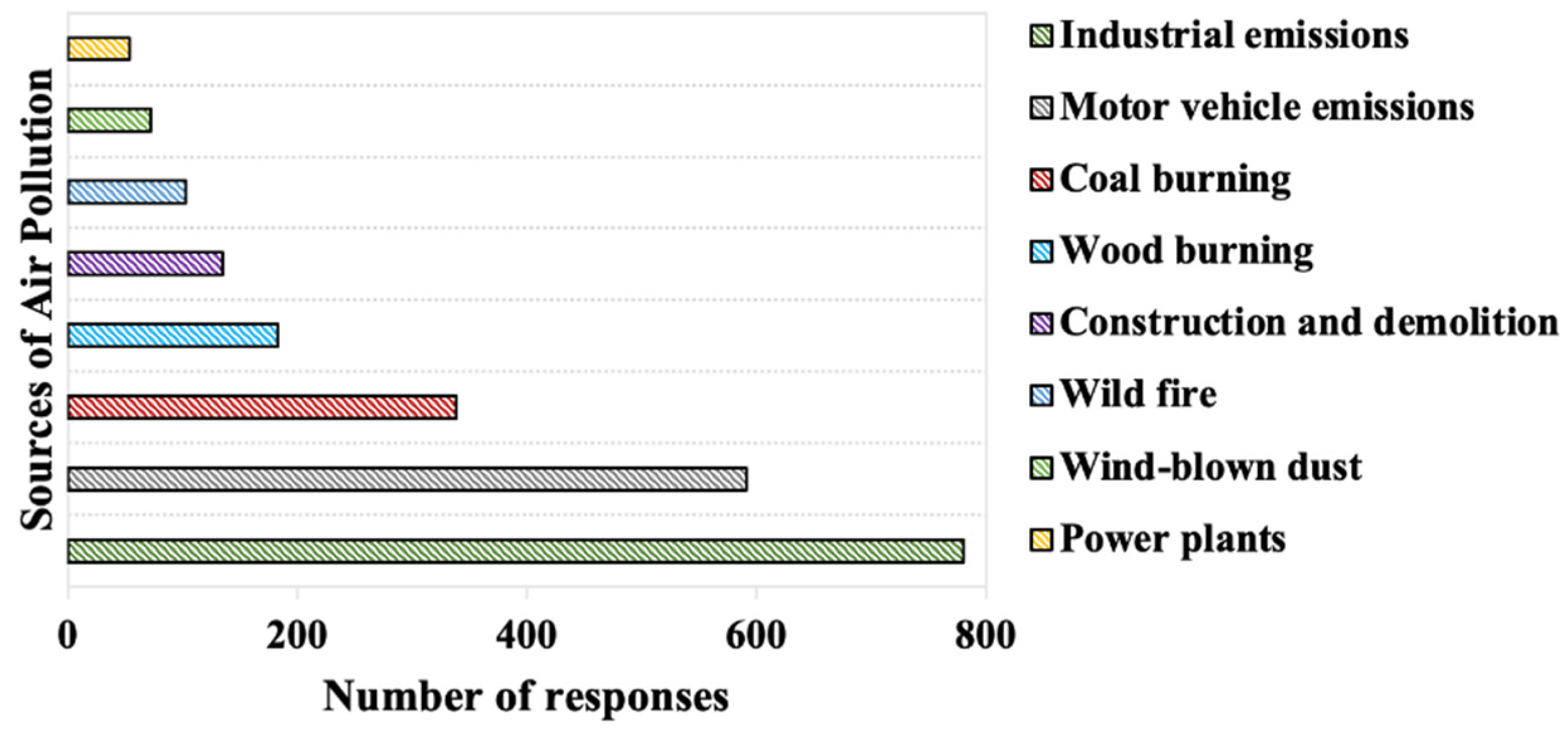

Table 8 summarizes the relationship between participants’ knowledge of air pollution-related topics (maximum score: 14.0) and demographics. Most participants consider industrial emissions, vehicle exhaust, and coal burning as the major sources of air pollution (

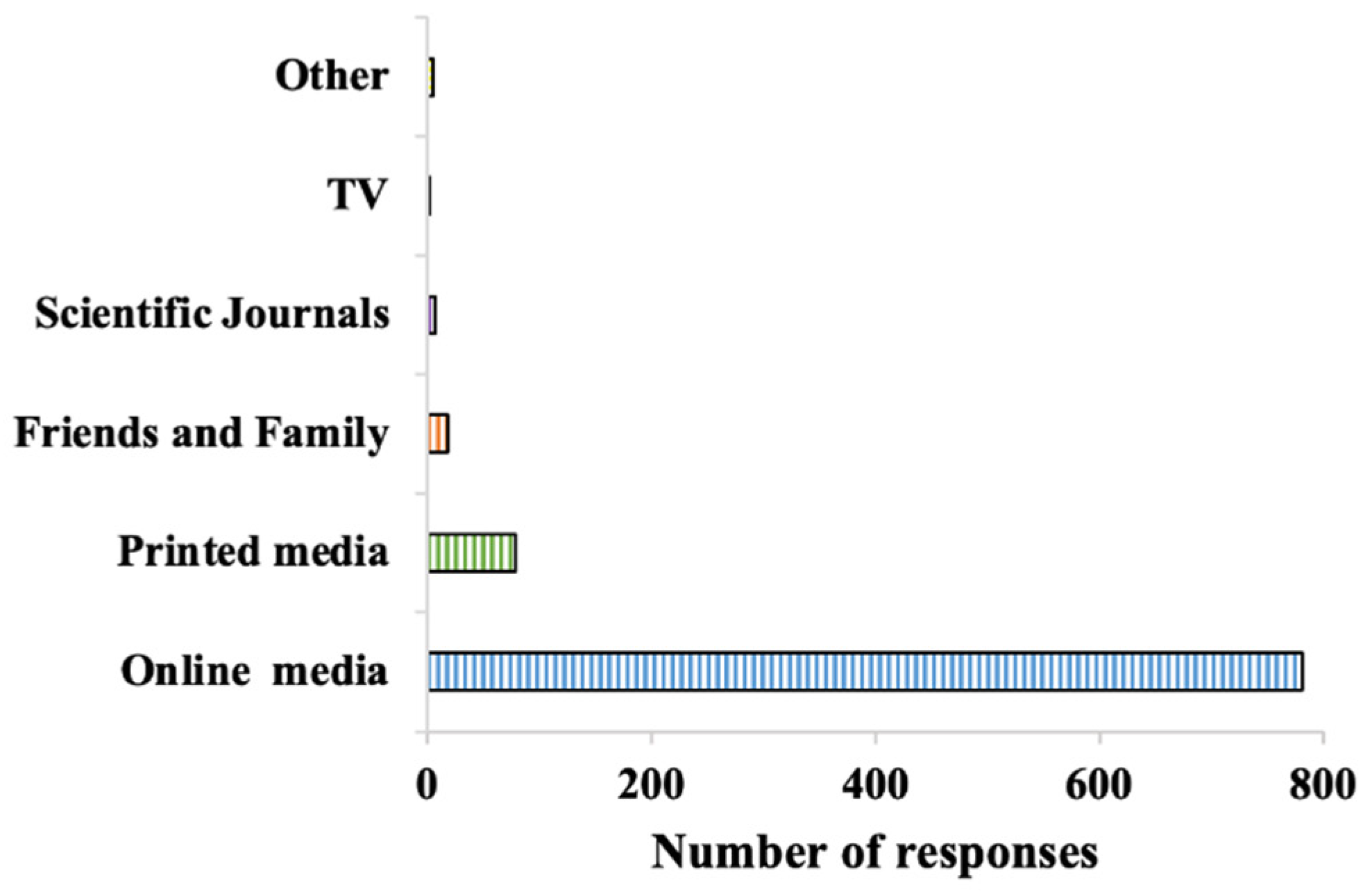

Figure 2). Furthermore, almost all respondents (99.9%) use online resources for air pollution-related information (

Figure 3). The knowledge score was considerably low and varied significantly (p<.001) by age category, education, employment status, environment where respondents spend most of their time, average monthly household income, it also varied by health status (asthma (p=0.002) and COPD (p =0.05)). A higher level of knowledge was noted among participants in the 18–24 age category (mean=6.75±3.14, p<.001). Overall, participants who obtained a graduate degree demonstrated a higher level of knowledge of air pollution-related topics (mean=6.44 ± 2.84, p<.001).

The students, participants who worked in urban environments, and those with higher economic status (i.e., average monthly household income>1,000,000 KZT) showed a higher level of knowledge compared to the rest of the population (

Table 8). Notably, participants diagnosed with asthma had the highest average knowledge score (mean=7.20±3.84, p=0.002).

3.5. Attitude Toward Environmental Protection and Willingness to Pay

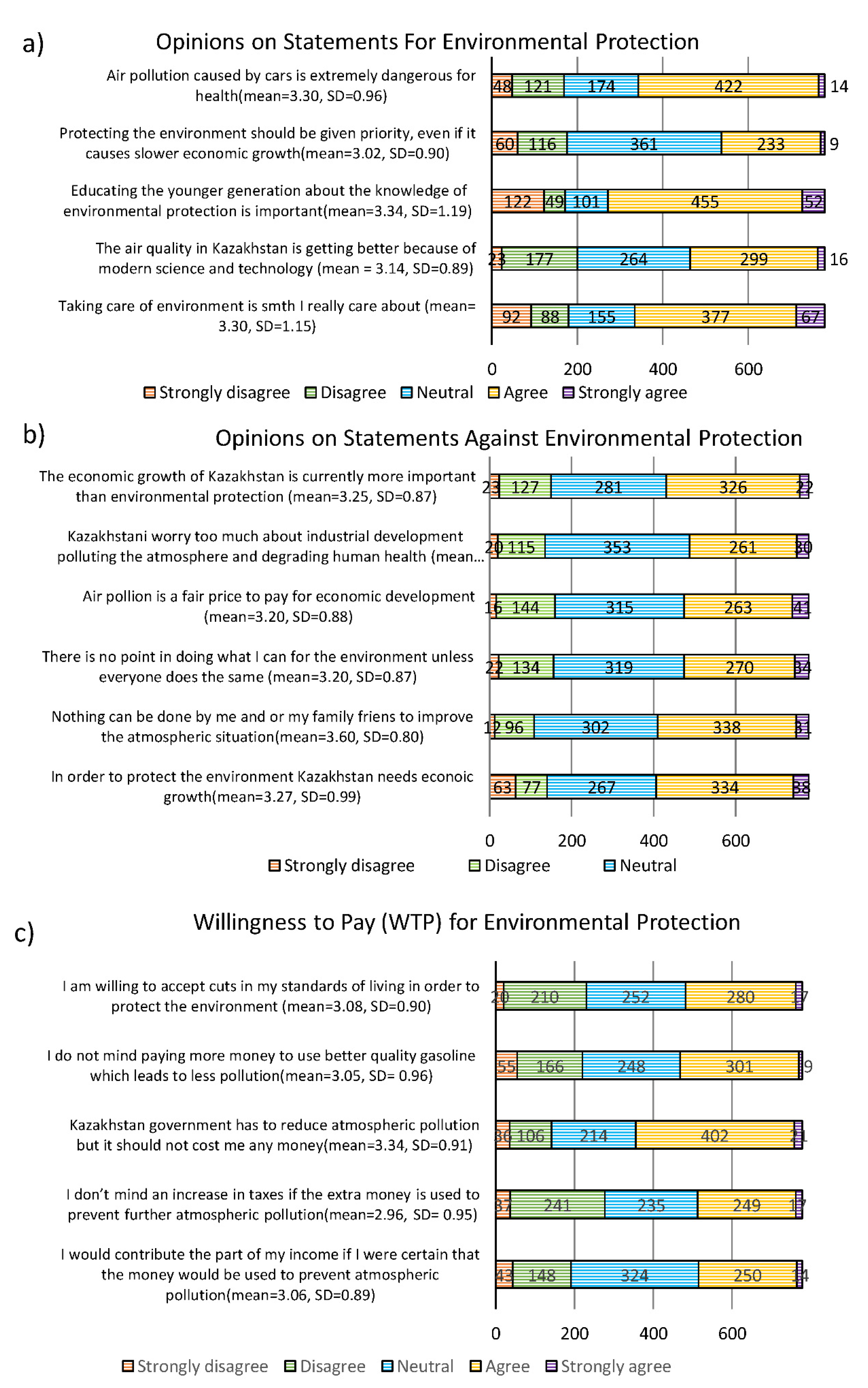

Most participants were largely in agreement with the statements regarding environmental protection, (mean score>3.00 (neutral response)) (

Figure 4). Almost 30% of the respondents prioritized environmental protection over economic growth. The strongest agreement was noted for statements about the importance of environmental literacy (mean=3.34) (“Educating younger generations about the knowledge of environmental protection is important.”) and general attitude towards environmental protection (mean=3.30) (“Taking care of the environment is something I really care about.”).

Opinions against environmental protection were mostly neutral or supportive (mean>3.20). Almost 42% of the study population supported the statement “The economic growth of Kazakhstan is currently more important than environmental protection.” Almost half of the respondents (43.2%) were skeptical about the individual actions that can be taken to improve air quality (“Nothing can be done by me or my family or friends to improve the atmospheric situation.”). Moreover, one-third of the participants expressed a lack of motivation towards individual actions unless the initiative is supported in the community (“There is no point in doing what I can for the environment unless everyone does the same.”).

Most respondents either demonstrated a WTP for environmental protection or remained neutral in their WTP statements (

Figure 4). Half of the respondents (51.4%) supported the idea of governmental intervention for environmental protection without self-involvement (mean=3.34) (“Kazakhstan’s government has to reduce atmospheric pollution, but it should not incur any costs to me.”), only 32.0% of the surveyed population expressed their WTP extra taxes for enhancing air quality (mean=2.96) (“I do not object to a tax increase if the additional funds are utilized to prevent further atmospheric pollution.”). Furthermore, 36.0% of participants expressed their preparedness to accept a reduction in their standard of living to protect the environment.

4. Discussion

The results of the SEM analysis highlight the significance of local air quality knowledge and its effect on the public perception of national air pollution and the economy. This resonates with other studies where knowledge and education are prime factors in improving environmental attitudes (Sudarmadi et al., 2001; Meinhold & Malkus, 2005). It suggests that increasing environmental literacy among the general public should be considered a priority to promote pro-environmental behavior. In addition, since almost all respondents use online resources for air pollution-related information, it is crucial to disseminate knowledge of air pollution and related health effects through easily accessible means to benefit a population with varying socioeconomic backgrounds (Finn & Fallon, 2017). One possible way to spread environmental knowledge is through online platforms (e.g., social media) that have expanded in recent years. Yang & Wu (2019) investigated the effect of using social media for health-related information and its correlation with protective behavior during episodes of high air pollution in China. Results revealed that using social media for health-related information predicted the users’ attitude towards protective behavior (e.g., wearing dust masks during haze episodes).

The bivariate analysis further supported the impact of participants’ knowledge on their environmental attitudes and perceptions. Similar to the present study, Hou et al. (2021) found a moderate level of ambient air pollution health literacy among the respondents, and they observed an association between literacy level and specific covariates such as education, living arrangement, marital status, and area of residence. However, Odonkor and Mahami (2020), which assessed knowledge, attitudes, and perception of air pollution in Accra, Ghana, revealed that a low level of education and elderly age were associated with lower literacy regarding air pollution and related health effects. The highest level of environmental knowledge was evident for participants with a graduate degree, which suggests that formal education is a leading factor in promoting environmental awareness. However, within the context of Kazakhstan, despite 51.7% of the employed population having a bachelor’s degree (Bureau of National Statistics, 2022), the prevailing majority still demonstrates a low level of environmental literacy. Interestingly, some countries (e.g., Germany, Sweden) (Grund & Brock, 2022) with reported lower percentages of bachelor graduates show higher levels of public awareness of environmental issues. Moreover, in China, for instance, where tertiary education is acquired by only 10% of the population between the ages of 25 and 64 (OECD, 2023), environmental education is a requirement for elementary and secondary school levels (Wu, 2012). Moreover, a study by Clayton et al., 2018 which assessed the level of knowledge and environmental attitude among 1,433 Chinese students and adults, revealed a moderate level of knowledge (14.3 and 15.1 points out of 22 for adults and university students, respectively) and high intention for pro-environmental behavior. This implies the existence of additional confounding variables influencing environmental literacy, in addition to institutional knowledge.

A low level of environmental knowledge can explain the current perception of air quality among Astana residents. In general, the respondents do not consider the current local air quality as a threat to public health. It should be noted that Astana and Almaty (the second major city in the country) were ranked as the most polluted cities in Kazakhstan according to API, with substantial regional variation in airborne pollutants concentration (Kerimray et al., 2018). A collaborative effort between the World Bank and the Ministry of Environment and Water Resources of Kazakhstan also states concentrations of airborne pollutants such as PM10, NO2, and SO2 exceeding the European Union air quality guidelines in ten Kazakhstani cities (The World Bank, 2021).

The increased activity of coal-fired CHPPs and domestic coal combustion during winter months substantially contribute to serious degradation of air quality due to the increased demand for heating during extreme cold episodes. The annual coal consumption of CHPPs in Astana is estimated at 3.2 million tons. On top of this, according to data from a 2018 household survey, two-thirds of Kazakhstani households still use solid fuels such as coal, biomass, and wood for heating (The World Bank, 2021).

By effectively conveying the health hazards associated with air pollution, researchers can promote public awareness about the issue and motivate the general population to follow air pollution mitigation strategies. Moreover, the identification of factors affecting the public perception of air pollution and related health effects can further aid in developing relevant and accessible communication tools that are tailored to specific public concerns and knowledge gaps.

Pro-environmental behavior can also be effectively promoted by considering individual intentions (Bamberg & Möser, 2007). The intention for individual actions is associated with personal self-consciousness and self-identity (Huang et al., 2020). Studies also indicate that individuals who perceive themselves as environmentalists are more likely to act (Tabernero et al., 2015; Carfora et al., 2017). Moreover, a perceived lack of control over environmental issues affects the willingness to take individual actions and pay for environmental protection, in the form of environmental taxes and prices for higher-quality gasoline (Vicente et al., 2021).

There is a common belief that developing countries are less concerned with environmental protection because their focus is driven by survival and material concerns. However, emerging evidence also suggests no association between national income and WTP for environmental protection. Some studies indeed speculate that due to presumably higher pollution levels, environmental protection is a greater concern for developing countries (Dunlap & York, 2016; Shao et al., 2018). In the present study, SEM analysis revealed a relationship between WTP for environmental protection and environmental attitude, indicating that respondents’ readiness to spend money on environmental protection shapes their attitude toward environmental issues and gives them a sense of control over their own actions. These findings support the importance of a perceived lack of control over environmental issues and its association with behavior intentions and attitudes toward pro-environmental behavior. In the bivariate analysis, the majority of the respondents expressed either WTP for environmental protection or remained neutral in their WTP statements, which further supports the results of the SEM analysis.

One form of payment for environmental preservation is environmental taxation. New environmental regulations introduced penalties and fees to minimize noncompliance with emission standards in Kazakhstan. However, the emission limit values (ELVs) established for industrial plants in Kazakhstan are higher than those recommended by international guidelines (e.g., the EU Industrial Emissions Directive) (Assanov et al., 2021). Moreover, environmental sanctions are more directed toward government budget revenue rather than toward environmental protection (Abakhanov, 2020). However, in 2021, Kazakhstan adopted its Environmental Code that established the payment for negative environmental impact (NEI), which is subjected to a gradual increase every three years for large corporations. The estimation of NEI for stationary sources is set based on the emission concentrations. The base pollution tax for the emissions within ELVs also depends on the monthly calculation index (MCI) and tax coefficient per ton of pollutant. Stationary sources with emissions higher than ELVs are subjected to administrative penalties and environmental damage payments (The World Bank, 2021). Almost 40% of the respondents support paying more for higher quality fuel if it improves air quality (“I do not mind paying more money to use better quality gasoline, which leads to less pollution.”). For mobile sources (e.g., passenger vehicles), the pollution tax is based on the engine size and type of fuel (e.g., unleaded gasoline, diesel fuels, compressed gas) with different rates for summer (June-October) and winter (November-May) periods (The World Bank, 2021).

6. Conclusion

The present study assessed the perception, attitude, and knowledge of the local air quality among adult, urban residents of Astana, a city with a population boom situated in Kazakhstan which is a developing economy. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was the tool used to investigate the causal relationship between perceived air quality, knowledge of air pollution-related topics, and willingness to pay (WTP) for environmental protection.

SEM suggests that knowledge is the key factor in enhancing awareness and perception of national air pollution levels.

To successfully implement air pollution mitigation interventions and provide continuous education to the local population regarding air quality and associated health effects, it is crucial to prioritize increasing public environmental literacy via online channels (e.g., social media) as online resources were among the most common sources of information.

Respondents with low environmental literacy classified Astana as a moderately polluted region with no association with adverse health outcomes (i.e., perception underestimating the reality), while those engaged in industrial work considered it a highly polluted area associated with health hazards.

Respondents with graduate degrees showed a higher level of knowledge (p<.001) of air pollution topics, suggesting that providing further financial and technological assistance to higher education would be suggested.

A moderate agreement was observed among the population groups with the statements for environmental protection and WTP statements.

Only a minority of the general public supported increasing tax rate and a reduced standard of living (32.0% and 36.0%, respectively) as measures supporting environmental protection. SEM analysis demonstrated that financial contribution (e.g., increased taxes) can enhance overall attitude towards environmental protection by strengthening environmental attitude, regardless of the limited support for financial measures among the public.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.K., A.A., M.G.; methodology, F.K., A.A., M.G.; software, A.A. and A. T.; validation, A.A. and A. T.; formal analysis, A.A. and A. T.; investigation, A.A. and A. T.; resources, F.K.; data curation, A.A. and A. T.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A. and A. T.; writing—review and editing, A.A., A. T., F.K., E.A., and M.G.; visualization, A.A. and A. T.; supervision, F.K., E.A., and M.G.; project administration, F.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Nazarbayev University Faculty Development Competitive Research Grant Program (Funder Project Reference: 280720FD1904).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nazarbayev University (protocol code 564/28042022; May 16, 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The survey questionnaire used in the present study:

-

What is your age?

[ ] less than 18

[ ] 18-24

[ ] 25-34

[ ] 35-44

[ ] 45-54

[ ] 55-64

[ ] 65+

-

What is your gender?

[ ] Male

[ ] Female

[ ] Prefer not to answer

-

What is your highest qualification?

[ ] Secondary school degree

[ ] High school degree

[ ] Specialized secondary education

[ ] Bachelor’s degree

[ ] Master’s degree or above

-

What is your current employment status?

[ ] Full-time employment

[ ] Part-time employment

[ ] Self-employed

[ ] Unemployed

[ ] Student

[ ] Retired

-

What is the environment that you spend most of your day in?

[ ] Environment where air quality is not a concern (e.g., school office)

[ ] Industrial environment where air quality is a concern (e.g., metal workshops, heating, and power plants, etc.)

[ ] Urban environment where air quality is a concern (e.g., highway toll collection, truck driver, taxi driver, etc.)

[ ] Another environment where air quality is a concern (please specify)

[ ] Not working

[ ] Home environment

-

What is your average monthly household income?

[ ] <100,000 KZT

[ ] 100,000-250,000 KZT

[ ] 250,001-500,000 KZT

[ ] 500,001-1,000,000 KZT

[ ] >1,000,000 KZT

-

Please indicate if you have the following chronic conditions.

High blood pressure [Yes] [No]

Cardiovascular conditions [Yes] [No]

Diabetes [Yes] [No]

Asthma [Yes] [No]

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) [Yes] [No]

-

Overall, how would you rate the atmospheric condition at the region you live in?

[ ] Highly polluted

[ ] Moderately polluted and causes harm

[ ] Moderately polluted but causes no harm

[ ] Not polluted at all

-

What is your source of information about air quality and air pollution-related topics? (Select all that apply)

[ ] Online media (e.g., social networks, websites)

[ ] Printed media (e.g., books, brochures, magazines)

[ ] Friends and Family

[ ] Scientific Journals

[ ] TV

-

Please select all that you think contributes to ambient air pollution.

[ ] Industrial emissions

[ ] Motor vehicle emissions

[ ] Coal burnings

[ ] Woodburning

[ ] Construction and Demolition

[ ] Wildfires

[ ] Wind-blown dust

[ ] Power/heating plants

Below are a number of statements. Please select whether you believe the statement is more likely to be TRUE or FALSE. If you really have no idea, only then you can proceed to choose ‘I don’t know’.

- 11.

-

The National Hydrometeorological Service of Kazakhstan “Kazhydromet” measures ambient air quality continuously in Astana.

[ ] True

[ ] False

[ ] I don’t know.

- 12.

-

Astana is currently ranked the number one most polluted city in the country according to the Air Pollution Index (API).

[ ] True

[ ] False

[ ] I don’t know.

- 13.

-

The major cause of respiratory and cardiovascular conditions is air pollution.

[ ] True

[ ] False

[ ] I don’t know

- 14.

-

Nitrogen oxides (NOx) which are serious air pollutants are mainly emitted by vehicles.

[ ] True

[ ] False

[ ] I don’t know

- 15.

-

Poor air quality with an Air Pollution Index (API) of 100 is not likely to cause adverse human health effects to the general public.

[ ] True

[ ] False

[ ] I don’t know

- 16.

-

Sulfur dioxide (SO2) which is a serious air pollutant is mainly coming from coal-fired power plants and residential heating.

[ ] True

[ ] False

[ ] I don’t know

Please use the following scale to indicate your level of agreement or disagreement with each statement.

| 1-Strongly disagree |

2-Disagree |

3-Neutral |

4-Agree |

5-Strongly agree |

| 17 |

Taking care of the environment is something I really care about. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| 18 |

In order to protect the environment, Kazakhstan needs economic growth. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| 19 |

I would contribute part of my income if I were certain that the money would be used to prevent atmospheric pollution. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| 20 |

Nothing can be done by me or my family / friends to improve the current atmospheric situation. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| 21 |

I do not mind an increase in taxes if the extra money is used to prevent further atmospheric pollution. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| 22 |

There is no point in doing what I can for the environment unless everyone does the same. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| 23 |

Air pollution is a fair price to pay for economic development. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| 24 |

Kazakhstan government has to reduce atmospheric pollution, but it should not cost me any money. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| 25 |

The air quality in Kazakhstan is getting better because of modern science and technology. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| 26 |

Kazakhstani worry too much about industrial development polluting the atmosphere and degrading human health. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| 27 |

Educating the younger generation about the knowledge of environmental protection is important. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| 28 |

Protecting the environment should be given priority, even if it causes slower economic growth. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| 29 |

I do not mind paying more money to use better quality gasoline which leads to less pollution. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| 30 |

The economic growth of Kazakhstan is currently more important than environmental protection. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| 31 |

I am willing to accept cuts in my standards of living in order to protect the environment. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| 32 |

Air pollution caused by cars is extremely dangerous for health. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

Appendix B

Table A1.

Perception of air quality among respondents.

Table A1.

Perception of air quality among respondents.

| Demographic Characteristics |

Highly polluted |

Moderately polluted/cause harm |

Moderately polluted/cause no harm |

Not polluted at all |

χ2 |

p |

| n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

|

| Age category |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

73.5 |

<0.001 |

| 18-24 |

10 |

17.0 |

22 |

37.3 |

21 |

35.6 |

6 |

10.2 |

|

|

| 25-34 |

29 |

12.7 |

46 |

20.2 |

109 |

47.8 |

44 |

19.3 |

|

|

| 35-44 |

39 |

21.2 |

27 |

14.7 |

97 |

52.7 |

21 |

11.4 |

|

|

| 45-54 |

50 |

34.3 |

36 |

24.7 |

48 |

32.9 |

12 |

8.2 |

|

|

| 55-64 |

23 |

30.3 |

16 |

21.1 |

29 |

38.2 |

8 |

10.5 |

|

|

| 65+ |

13 |

14.9 |

36 |

41.4 |

25 |

28.7 |

13 |

14.9 |

|

|

| Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

48.2 |

<0.001 |

| Male |

105 |

28.9 |

100 |

27.4 |

119 |

32.6 |

41 |

11.2 |

|

|

| Female |

59 |

14.3 |

82 |

19.81 |

210 |

50.7 |

63 |

15.2 |

|

|

| Undefined |

0 |

0.00 |

2 |

100 |

0 |

0.00 |

0 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Education |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

219 |

<0.001 |

| Secondary school degree |

1 |

12.5 |

1 |

12.5 |

5 |

62.5 |

1 |

12.5 |

|

|

| High school degree |

7 |

9.72 |

4 |

5.56 |

19 |

26.4 |

42 |

58.3 |

|

|

| Specialized secondary education |

69 |

29.7 |

39 |

16.8 |

86 |

37.1 |

38 |

16.4 |

|

|

| Bachelor’s degree |

74 |

19.0 |

96 |

24.6 |

199 |

51.0 |

21 |

5.38 |

|

|

| Master’s degree or above |

13 |

16.5 |

44 |

55.7 |

20 |

25.3 |

2 |

2.53 |

|

|

| Employment status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

236 |

<0.001 |

| Full-time employment |

15 |

14.3 |

52 |

49.5 |

31 |

29.5 |

7 |

6.67 |

|

|

| Part-time employment |

8 |

11.6 |

4 |

5.80 |

16 |

23.2 |

41 |

59.4 |

|

|

| Self-employed |

70 |

29.5 |

38 |

16.0 |

92 |

38.8 |

37 |

15.6 |

|

|

| Unemployed |

65 |

19.9 |

67 |

20.6 |

177 |

54.3 |

17 |

5.21 |

|

|

| Student |

4 |

10.0 |

21 |

52.5 |

13 |

32.5 |

2 |

5.00 |

|

|

| Retired |

2 |

50.0 |

2 |

50.0 |

0 |

0.00 |

0 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Environment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

191 |

<0.001 |

| Not a concern |

66 |

15.6 |

75 |

17.8 |

201 |

47.6 |

80 |

19.0 |

|

|

| Industrial environment/concern |

55 |

69.6 |

6 |

7.6 |

15 |

19.0 |

3 |

3.08 |

|

|

| Urban environment/concern |

8 |

9.41 |

30 |

35.3 |

33 |

38.8 |

14 |

16.5 |

|

|

| Another environment/concern |

4 |

18.2 |

11 |

50.0 |

5 |

22.7 |

2 |

9.09 |

|

|

| Not working |

14 |

26.9 |

13 |

25.0 |

22 |

42.3 |

3 |

5.77 |

|

|

| Home environment |

17 |

14.1 |

49 |

40.5 |

53 |

43.8 |

2 |

1.65 |

|

|

| Average monthly household income |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

68.1 |

<0.001 |

| <100,000 KZT |

60 |

21.3 |

49 |

17.4 |

123 |

43.6 |

50 |

17.7 |

|

|

| 100,000-250,000 KZT |

62 |

21.3 |

57 |

19.6 |

139 |

47.8 |

33 |

11.3 |

|

|

| 250,001-500,000 KZT |

16 |

16.3 |

33 |

33.7 |

45 |

45.9 |

4 |

4.08 |

|

|

| 500,001-1,000,000 KZT |

16 |

31.4 |

14 |

27.5 |

9 |

17.6 |

12 |

23.5 |

|

|

| >1,000,000 KZT |

10 |

17.0 |

31 |

52.5 |

13 |

22.0 |

5 |

8.47 |

|

|

| Health status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| High blood pressure |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

54.9 |

<0.001 |

| Yes |

71 |

37.4 |

42 |

22.1 |

45 |

23.7 |

32 |

16.8 |

|

|

| No |

93 |

15.7 |

142 |

24.0 |

284 |

48.1 |

72 |

12.2 |

|

|

| Cardiovascular conditions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.63 |

0.89 |

| Yes |

5 |

23.8 |

6 |

28.56 |

8 |

38.1 |

2 |

9.52 |

|

|

| No |

159 |

20.9 |

178 |

23.4 |

321 |

42.2 |

102 |

13.4 |

|

|

| Diabetes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.16 |

0.54 |

| Yes |

1 |

12.5 |

2 |

25.0 |

5 |

62.5 |

0 |

0.00 |

|

|

| No |

163 |

21.1 |

182 |

23.5 |

324 |

41.9 |

104 |

13.5 |

|

|

| Asthma |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6.87 |

0.08 |

| Yes |

1 |

9.09 |

6 |

54.6 |

4 |

36.4 |

0 |

0.00 |

|

|

| No |

163 |

21.2 |

178 |

23.1 |

325 |

42.2 |

104 |

13.5 |

|

|

| COPD |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7.98 |

0.05 |

| Yes |

0 |

0.00 |

6 |

50.0 |

6 |

50.0 |

0 |

0.00 |

|

|

| No |

164 |

21.3 |

178 |

23.2 |

323 |

42.0 |

104 |

13.5 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Total |

164 |

21.0 |

184 |

23.6 |

329 |

42.1 |

104 |

13.3 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References

- Abakhanov, E. (2020). New Environmental Code of Kazakhstan: Expectations and Prospects. Central Asian Bureau for Analytical Reporting. https://cabar.asia/en/new-environmental-code-of-kazakhstan-expectations-and-prospects.

- Assanov, D., Zapasnyi, V., & Kerimray, A. (2021). Air quality and industrial emissions in the cities of Kazakhstan. Atmosphere, 12(3), 314. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [CrossRef]

- Awe, Y., Larse, B., Hoossei, S., & Sánchez-Triana, E. (2020). (rep). The Global Health Cost of Ambient PM2.5 Air pollution. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/202401605153894060/World-The-Global-Cost-of-Ambient-PM2-5-Air-Pollution.pdf.

- Aztatzi-Aguilar, O., Valdés-Arzate, A., Debray-García, Y., Calderón-Aranda, E., Uribe-Ramirez, M., Acosta-Saavedra, L., Gonsebatt, M., Maciel-Ruiz, J., Petrosyan, P., Mugica-Alvarez, V., Gutiérrez-Ruiz, M., Gómez-Quiroz, L., Osornio-Vargas, A., Froines, J., Kleinman, M., & De Vizcaya-Ruiz, A. (2018). Exposure to ambient particulate matter induces oxidative stress in lung and aorta in a size- and time-dependent manner in rats. Toxicology Research and Application, 2. [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S., & Möser, G. (2007). Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of Psycho-Social Determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 27(1), 14–25. [CrossRef]

- Carducci, A., Fiore, M., Azara, A., Bonaccorsi, G., Bortoletto, M., Caggiano, G., Calamusa, A., De Donno, A., De Giglio, O., Dettori, M., Di Giovanni, P., Di Pietro, A., Facciolà, A., Federigi, I., Grappasonni, I., Izzotti, A., Libralato, G., Lorini, C., Montagna, M., … Ferrante, M. (2021). Pro-environmental behaviors: Determinants and obstacles among Italian university students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 3306. [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V., Caso, D., Sparks, P., & Conner, M. (2017). Moderating effects of pro-environmental self-identity on pro-environmental intentions and behavior: A multi-behavior study. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 53, 92–99. [CrossRef]

- Chin, Y., De Pretto, L., Thuppil, V., & Ashfold, M. (2019). Public awareness and support for environmental protection–A focus on air pollution in peninsular Malaysia. PLoS ONE, 14(3). [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S., Bexell, S., Xu, P., Tang, Y., Li, W., & Chen, L. (2019). Environmental literacy and nature experience in Chengdu, China. Environmental Education Research, 25(7), 1105–1118. [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R., & York, R. (2016). The globalization of environmental concern and the limits of the postmaterialist values explanation: Evidence from four multinational surveys. The Sociological Quarterly, 49(3), 529–563. [CrossRef]

- Farina, F., Sancini, G., Mantecca, P., Gallinotti, D., Camatini, M., & Palestini, P. (2011). The acute toxic effects of particulate matter in mouse lung are related to size and season of collection. Toxicology Letters, 202(3), 209–217. [CrossRef]

- Finn, S., & O’Fallon, L. (2017). The emergence of environmental health literacy–from its roots to its potential. Environ Health Perspectives, 125(4). [CrossRef]

- Grund, J., & Brock, A. (2020). Education for Sustainable Development in Germany: Not just desired but also effective for transformative action. Sustainability, 12(7), 2838. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Hult, G., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2018). A primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://www.pls-sem.net/pls-sem-books/advanced-issues-in-pls-sem/.

- Hou, W., Huang, Y., Lu, C., Chen, I., Lee, P., Lin, M., Wang, Y., Sulistyorini, L., & Li, C. (2021). A national survey of ambient air pollution health literacy among adult residents of Taiwan. BMC Public Health, 21, 1604. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., Ou, J., & Gao, J. (2020). Nationwide response to air pollution: Environmental behavior model based on self-identity and social identity process. The International Journal of Electrical Engineering & Education, 0(0). [CrossRef]

- Hungerford, H., & Volk, T. (1990). Changing learner behavior through environmental education. The Journal of Environmental Education, 21(3), 8–21. [CrossRef]

- Janjua, S., Powell, P., Atkinson, R., Stovold, E., & Fortescue, R. (2019). Individual-level interventions to reduce personal exposure to outdoor air pollution and their effects on long-term respiratory conditions. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, F., & Fussell, J. (2012). Size, source and chemical composition as determinants of toxicity attributable to ambient particulate matter. Atmospheric environment, 60, 504–526. [CrossRef]

- Keller, C., Bostrom, A., Kuttschreuter, M., Savadori, L., Spence, A., & White, M. (2012). Bringing appraisal theory to environmental risk perception: A review of conceptual approaches of the past 40 years and suggestions for future research. Journal of risk research, 15(3), 237–256. [CrossRef]

- Kerimray, A., Bakdolotov, A., Sarbassov, Y., Inglezakis, V., & Poulopoulos, S. (2018). Air pollution in Astana: Analysis of recent trends and air quality monitoring system. Materials Today: Proceedings, 5(11), 22749–22758. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., & Hu, B. (2018). Perceived health risk, environmental knowledge, and contingent valuation for improving air quality: New evidence from the Jinchuan mining area in China. Economics & Human Biology, 31, 54–68. [CrossRef]

- Laumbach, R., Meng, Q., & Kipen, H., (2015). What can individuals do to reduce personal health risks from air pollution? Journal of Thoracic Disease, 7(1), 96–107. [CrossRef]

- Maione, M., Mocca, E., Eisfeld, K., Kazepov, Y., & Fuzzi, S. (2021). Public perception of air pollution sources across Europe. Ambio, 50(6), 1150–1158. [CrossRef]

- Meinhold, J., & Malkus, A. (2005). Adolescent environmental behaviors. Environment and Behavior, 37(4), 511–532. [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics and agency for strategic planning and reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan. (2022). Demographic Statistics. The Agency for strategic planning and reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan. https://taldau.stat.gov.kz/ru/NewIndex/GetIndex/703831?keyword=.

- Odonkor, S., & Mahami, T. (2020). Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceptions of Air Pollution in Accra, Ghana: A Critical Survey. Journal of Environmental and Public Health, 2020. [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2023). China: Overview of the education system (EAG 2022). Education GPS - China - overview of the education system (EAG 2022). https://gpseducation.oecd.org/CountryProfile?primaryCountry=CHN&treshold=10&topic=EO#:~:text=Among%2025%2D64%20year%2Dolds,doctoral%20degrees%20combined%20with%201%25.

- Qian, X., Xu, G., Li, L., Shen, Y., He, T., Liang, Y., Yang, Z., Zhou, W., & Xu, J. (2016). Knowledge and perceptions of air pollution in Ningbo, China. BMC Public Health, 16(1). [CrossRef]

- Rajper, S., Ullah, S., & Li, Z. (2018). Exposure to air pollution and self-reposted effects on Chinese students: A case study of 13 megacities. PLoS ONE, 13(3). [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, A., Ramondt, S., Van Bogart, K., & Perez-Zuniga, R. (2019). Public awareness of air pollution and health threats: Challenges and opportunities for communication strategies to improve environmental health literacy. Journal of Health Communication, 24(1), 75–83. [CrossRef]

- Saari, U., Damberg, S., Frömbling, L., & Ringle, C. (2021). Sustainable consumption behavior of Europeans: The influence of environmental knowledge and risk perception on environmental concern and behavioral intention. Ecological Economics, 189. [CrossRef]

- Saksena, S. (2012). Public perceptions of urban air pollution risks. Risk, Hazards and Crisis in Public Policy, 2(1), 19–37. [CrossRef]

- Shao, S., Tian, Z., & Fan, M. (2018). Do the rich have stronger willingness to pay for environmental protection? New evidence from a survey in China. World Development, 105, 83–94. [CrossRef]

- Sudarmadi, S., Suzuki, S., Kawada, T., Netti, H., Soemantri, S., & Tri Tugaswati, A. (2001). A Survey of perception, knowledge, awareness, and attitude in regard to environmental problems in a sample of two different social groups in Jakarta, Indonesia. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 3(2), 169–183. [CrossRef]

- Tabernero, C., Hernández, B., Cuadrado , E., Luque, B., Pereira, C. (2015). A multilevel perspective to explain recycling behaviour in communities. Journal of Environmental Management, 159, 192–201. [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. (2021). (rep.). Cost-Effective Air Quality Management in Kazakhstan and Its Impact on Greenhouse Gas Emissions, (Report No. AUS0002588). International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099345012232191779/pdf/P1708700d2bd3a09093fa0cd27991d0662.pdf.

- Vassanadumrongdee, S., & Matsuoka, S. (2005). Risk perceptions and value of a statistical life for air pollution and traffic accidents: Evidence from Bangkok, Thailand. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 30(3), 261–287. [CrossRef]

- Vicente, P., Marques, C., & Reis, E. (2021). Willingness to pay for environmental quality: The effects of pro-environmental behavior, perceived behavior control, environmental activism, and educational level. SAGE Open, 11(4). [CrossRef]

- Wang, R., Yang, Y., Chen, R., Kan, H., Wu, J., Wang, K., Maddock, J., & Lu, Y. (2015). Knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) of the relationship between air pollution and children’s respiratory health in Shanghai, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(2), 1834–1848. [CrossRef]

- WHO. (2016). WHO releases country estimates on air pollution exposure and Health Impact. World Health Organization. Retrieved October 3, 2022, from https://www.who.int/news/item/27-09-2016-who-releases-country-estimates-on-air-pollution-exposure-and-health-impact.

- Wu, L. (2012). Exploring the New Ecological Paradigm Scale for Gauging Children’s Environmental Attitudes in China. The Journal of Environmental Education, 43 (2), 107–120. [CrossRef]

- Xue, J., Hu, S., Quiros, D., Ayala, A., & Jung, H. (2019). How do particle number, surface area, and mass correlate with toxicity of diesel particle emissions as measured in chemical and cellular assays? Chemosphere, 229, 559–569. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q., & Wu, S. (2019). How social media exposure to health information influences Chinese people’s health-protective behavior during air pollution: A theory of planned behavior perspective. Health Communication, 36(3), 324–333. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).