1. Introduction

Fungal keratitis (FK), a form of infectious keratitis primarily associated with species of Aspergillus, Candida, or Fusarium, is reported to be under-recognized and under-prioritized [

1,

2,

3]. Modern estimates report a global incidence of 1.5 million cases per year, with at least 60% of cases resulting in loss of vision in the affected eye despite the best available treatment [

1,

2,

4]. Yet, in a 2021 report by the Lancet Commission entitled “Global Eye Health: vision beyond 2020”, fungal keratitis was not mentioned [

5]. A lack of recognition may be due in part to the relative exclusivity of the disease to human populations of low-income, tropical regions [

2,

6]. This puts fungal keratitis at low priority for medical researchers in the United States and other developed countries.

For veterinary researchers in the U.S., however, fungal keratitis is of high priority due to the prevalence of the disease in equine populations. In horses, fungal keratitis is caused by the same fungal species implicated in human infection and has the same clinical symptoms [

7,

8,

9]. Further, veterinarians face many of the same obstacles to treatment as physicians. These include delayed clinical presentation and diagnosis, difficulty selecting and/or obtaining appropriate drugs, increasing fungal resistance to available drugs, and poor patient compliance due to the necessary high frequency of treatments [

8,

9,

10]. As a result of these challenges, medical management with modern antifungals is often not effective [

11]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for research of novel methods of treatment, including but not limited to broad-spectrum antifungal drugs, as well as methods and models that will reliably assess both

in vitro susceptibility and practical clinical efficacy.

The current gold standard method for evaluating antimicrobial susceptibility is the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assay [

12].

In vitro results, however, are notoriously challenging to interpret, particularly in absence of established drug breakpoints for most Aspergillus and Fusarium species [

13].

In vitro resistance in the face of clinical efficacy, and vice versa, are both regularly reported [

2,

9,

14,

15]. A driving factor of this incongruity is that traditional MIC assays exclusively test antifungals against a suspension of asexual fungal spores called conidia [

12,

16]. Many antifungals, such as the heavily relied-upon azole class, exert their effects on fungi at the conidial stage by disrupting germination, the process by which conidia elongate and branch into vegetatively and reproductively active hyphae [

17]. Therefore, drugs such as voriconazole, may be effective at inhibiting fungal growth

in vitro when introduced to susceptible conidia, and yet have very little impact clinically when introduced to an infection characterized by mature mycelia no longer undergoing extensive germination or hyphal elongation. To make a practical prediction regarding clinical efficacy of an antifungal, the drug must be evaluated against fungi of the same developmental stage or stages present in clinical infections. Histology of corneas infected with FK has demonstrated that hyphae predominate within the clinically infected eye [

15,

18]. Therefore, antifungal susceptibility testing methods need to be adapted to include the introduction of the drug to mature fungal hyphae in addition to conidia.

The purpose of this study was to characterize differences in fungal response and treatment efficacy when antifungal treatment is initiated at sequential stages of fungal development using

in vitro and

ex vivo methods. We hypothesized that fungi that have developed beyond the conidial germination and germ tube elongation stage will express decreased susceptibility to an antifungal drug given at the minimum inhibitory concentration compared to fungal conidia. To test this hypothesis, we investigated two methods of evaluating antifungal susceptibility against fungal conidia and hyphal growth stages. To evaluate the response and susceptibility of conidia to two antifungals

in vitro, an adaptation of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) reference standard M27-A4 was used. Modifications to the standard

in vitro protocol included the addition of two sample groups incubated for either 24 or 48 h prior to introducing an antifungal drug. The second method evaluated susceptibility using an

ex vivo porcine corneal cadaver model of intrastromal infection. In this model, the antifungal was introduced to sample groups at either the conidial stage, after 24 h or 48 h of incubation. For both methods, fungal growth inhibition was compared between sample groups treated at the conidial stage versus those treated at mixed hyphal stages. The antifungal drugs selected for this study were voriconazole, a 2nd generation triazole, and luliconazole, an imidazole [

17,

19]. Because the 24 and 48-h sample groups were designed to target fungal hyphae after spore germination and hyphal germ tube development, time-lapse confocal imaging was performed on Aspergillus and Fusarium in

in vitro and

ex vivo experiments to identify the incubation period necessary for conidial germination of both species.

4. Discussion

Conventional antifungal susceptibility testing (AST), by either CLSI or EUCAST reference standards, requires fungal susceptibility to be evaluated from the conidial pre-germination stage. However, clinical manifestations of filamentous fungal infection are typically characterized by the destructive presence of hyphae [

22]. To be practically useful, antifungal susceptibility results need to offer clinicians information on drug efficacy for both the conidial and hyphal stages of fungal development. This has long since been recognized; some of the earliest attempts at establishing antifungal susceptibility testing for filamentous fungi focused on standardizing hyphal inocula and comparing results to MICs obtained from conidia [

23,

24]. While it was recognized then that MICs obtained from hyphal inocula tended to be several times higher, difficulties establishing a reliable technique for obtaining pure hyphal inocula and for also measuring the growth ultimately discouraged the pursuit of hyphal MICs, and the reference standard became to use pure conidial inocula [

12]. As a result, treatment decisions in cases of many fungal diseases must be made without critical information about hyphal susceptibility. In the case of fungal keratitis, medical treatment failure is reported in up to 30% of cases [

15].

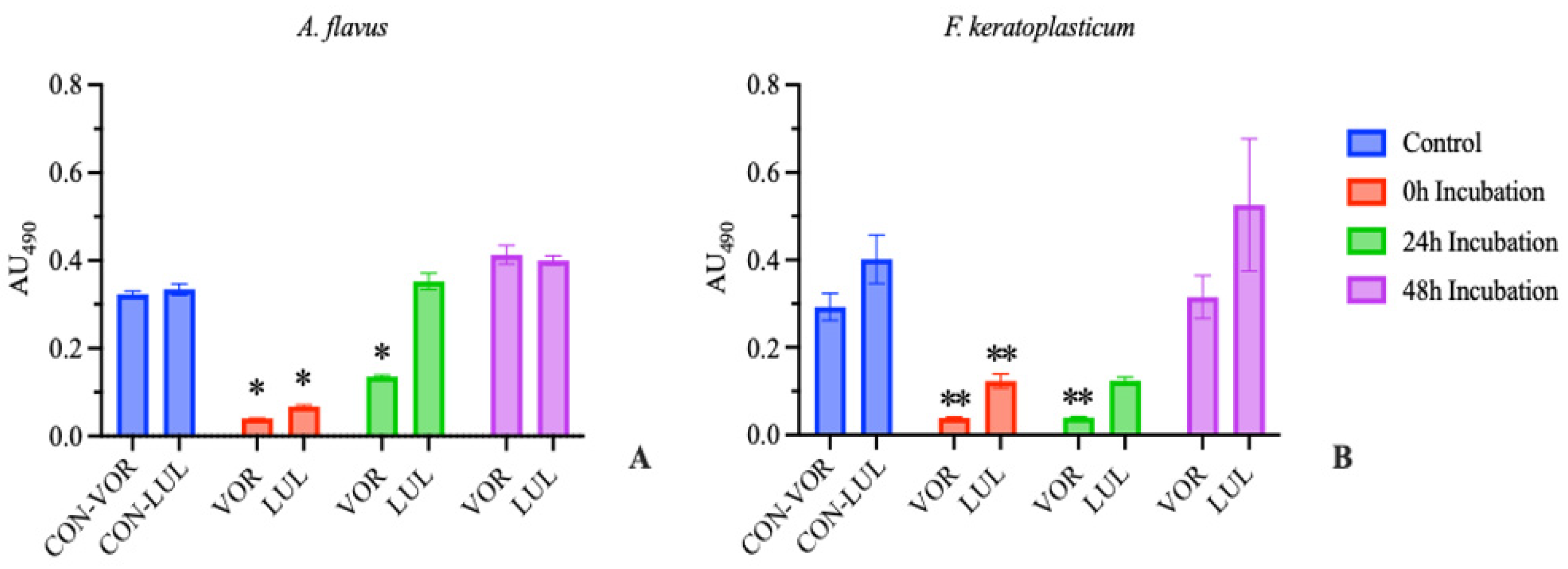

In this study, we designed and investigated a revised in vitro AST protocol based on the CLSI “Broth Microdilution for Molds” reference standard to complement previous studies using this experimental approach, which allows for comparison between antifungal susceptibility in fungal colonies treated with an antifungal agent prior to and following conidial germination. We first confirmed via microscopy that complete germination occurred in vitro within 24 h of incubation for A. flavus and F. keratoplasticum. We then performed AST with conidial suspensions which were allowed to incubate for 0, 24, or 48 h before introduction of the antifungal agent. The 24 h incubation group was designed to mimic conditions of early-stage confluent hyphal growth after conidial germination while the 48 h incubation group was designed to model late-presenting fungal infection typical of clinical experience. We found that only the 0 h incubation groups of either A. flavus or F. keratoplasticum were susceptible to the MIC of both voriconazole and luliconazole as determined by complete inhibition of visual growth.

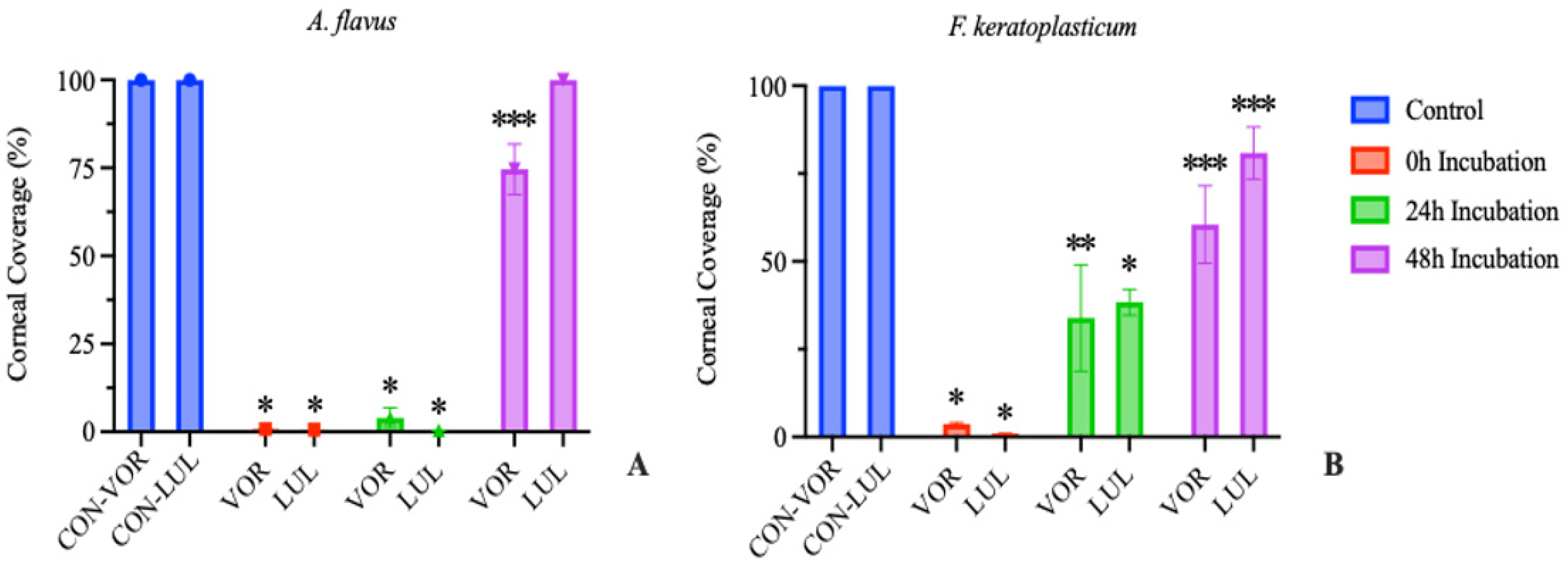

We further adapted our in vitro protocol to an ex vivo model of FK to investigate fungal response to treatment initiated by either pre- or post-conidial germination in a biologically relevant environment. Our data demonstrates that treating corneas infected with A. flavus in the ex vivo model with voriconazole (0.5 ug/mL) or luliconazole (0.1 ug/mL) after 24 h incubation resulted in >96% reduction in growth compared to the untreated controls. However, when treatment was initiated at 48 h post-inoculation, reduction in growth was limited to 25% or less. Treating corneas infected with F. keratoplasticum in our ex vivo model with either voriconazole (8 ug/mL) or luliconazole (0.2 ug/mL) after 24 h of incubation resulted in 61-66% reduction in growth, while treating after 48 h of incubation limited reduction in growth to <40% for voriconazole and <20% for luliconazole.

These results demonstrate a reduced response to azole treatment by fungal hyphae compared to conidia both in vitro and in a relevant ex vivo corneal infection model. This information is critical as clinical antifungal dosage recommendations are determined by MICs established against conidial suspensions, even though clinical infections are characterized by hyphae and mycelium which, as demonstrated in this study, exhibit a differential response to antifungal drugs depending on fungal development stage. Consequently, treating with the MIC of a topical azole antifungal may be effective in mitigating an infection associated with Aspergillus flavus in less than 48 h, or Fusarium in less than 24 h. However, once the fungal development stage progresses beyond conidial germination when hyphae and mycelium form within the corneal stroma, voriconazole and luliconazole delivered at the MIC as determined by traditional AST becomes less effective at reducing fungal growth and may even contribute to the development of antifungal resistance [

25]. Therefore, a better understanding and investigation of the mechanism(s) associated with differential response to azole drugs by fungal conidia and hyphae are warranted.

One plausible explanation for reduced drug efficacy observed with fungal hyphae is likely related to one of the principal mechanisms of resistance known to operate in filamentous fungi. Plasma membrane multidrug efflux pumps confer resistance to azoles by reducing the intracellular concentration of the drug [

25]. These pumps, which are common in species of Aspergillus and Fusarium, have been shown to undergo upregulation in response to azoles [

26]. Additionally, it is not known if the conidial stages of fungi possess these transporters. If they are absent at the conidial stage of development or present and activated post-germination, this may impact on antifungal drug activity against conidia versus hyphae. Further, Fusarium efflux pumps are reported to contribute to azole resistance to a greater degree than the efflux pumps found in Aspergillus [

25], which may in part explain our results of reduced growth inhibition in Fusarium cultures treated with an azole at 24 hours relative to Aspergillus.

In addition to these proposed mechanisms, Van de Sande et al. (2020) have suggested the cause of reduced antifungal efficacy against mature fungal specimens to be a matter of simple physical access [

27]. Fungal hyphae branch and grow at erratic angles forming complex, tortuous networks which may prevent antifungal agents from gaining access to much of the mycelial mass. Van de Sande determined that fungal inocula composed of a hyphal “clump” required a significantly greater inhibitory concentration compared to a homogenous suspension of hyphal fragments [

27]. Should this mechanism be driving hyphal resistance to antifungals, the emphasis of future research should be on investigating methods to improve azole access to the mycelial network in cells.

We propose using the models discussed here to perform susceptibility assays which target more advanced stages of fungal development, reflective of morphologies observed in clinical FK. While the classic

in vitro AST method has advantages, such as high-throughput screening of high isolate numbers, the

ex vivo model described here allows for better replication of the clinical scenario. Aside from being able to evaluate fungal response in the clinically relevant environment of the stroma, this model allows for the aqueous environment of the eye to refreshed regularly and for fresh application of antifungal drug daily over the course of the assay. This model also has the unique advantage of being able to investigate non-pharmaceutical treatment methods, such as photodynamic light therapy [

28]. To improve upon the limitations of this study, we plan to expanding the fungal species investigated to include A. fumigatus and F. falciforme, investigating additional therapies including but not limited to an extended selection and concentrations of antifungals, and use of additional diagnostics such as high-frequency ultrasound and histology of the inoculated corneas.

In conclusion, the pursuit of novel, improved therapies for fungal keratitis requires antifungal susceptibility testing that better predicts clinical efficacy. The experimental approaches and model presented in this study will be useful for understanding the interaction between antifungal agents and fungi across different stages of development, especially in the cornea. Our goal is that this improved understanding will be used to not only better inform clinicians on predicated antifungal efficacy but also inform research into developing novel methods of enhancing antifungal drug activity.