Introduction

Ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) is a term used to describe neoplastic epithelial abnormalities of conjunctiva and cornea, ranging from squamous dysplasia/intraepithelial neoplasia to invasive squamous cell carcinoma (1). OSSN is the most common tumor of the ocular surface whose primary site is the conjunctiva (2). Less than 0.2 instances per million people are thought to be affected by OSSN globally each year (3). The reported incidence of OSSN is 0.03–1.9 per 100 000 persons/year in the United States and Australia, whereas the incidence in Sub Saharan Africa (SSA) is 1.6–3.4 per 100 000 persons/year (4) (5) with Uganda having an incidence of 35 cases/million/year (6). The difference between the varying incidence rates has largely been attributed to the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) pandemic in SSA (5).

Conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma (Conjunctival SCC) incidence varies between 0.02 to 3.5 per 100,000 population per annum in the general population (7). The Africa’s age-standardized incidence of CSCC shows Eastern Africa having 1.25/100,000, followed by southern Africa, 1.16/100,000, and the lowest in northern Africa, 0.04/100,000 (8). The Sub-Saharan Africa CSCC distribution shows Uganda with 1.6/100,000 incidence (5). The incidence increases with decreasing latitude, being higher in countries located close to the equator (9). Patients with OSSN typically present in their sixties or seventies. However, the disease may develop earlier in immunocompromised people. (5).

Depending on the extent of dysplastic epithelium damage, the preinvasive OSSN is divided into three categories: mild, moderate, and severe. Conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia I (CIN I)/Mild dysplasia involves dysplasia in the lower one-third of the epithelium, Conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia II (CIN II)/ Moderate dysplasia involves dysplasia of the middle third, Conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia III (CIN III)/Severe dysplasia involves full thickness dysplasia, and Carcinoma in situ (CIS) involves full thickness dysplasia without breaking the basement membrane (10).

The Conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) is categorized by American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) as primary Tumor In-Situ (TIS) which embrace graded severity of epithelial dysplasia from CIN I (lower 1/3), CIN II (lower 2/3) and CIN III or Carcinoma In-Situ (CIS) for full epithelial thickness meanwhile Conjunctival SCC includes all invasive carcinoma with or without metastasis (primary tumor stage 1-4) (11). The two-tier grading of CIN involves, low-grade CIN (CIN I & II) and high-grade CIN (CIN III & CIS) (12). Islands of infiltrating cells that typically break through the epithelial basement barrier and invade the conjunctival stroma are what give invasive conjunctival SCC its name. These cells can be categorized as squamous or poorly differentiated, which are difficult to tell apart depending on how well-differentiated they are (10).

Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia (OSSN) distribution is dependent on risk factors including exposure to smoke, dust, ultraviolet light, human papillomavirus infection, old age, and male sex (5 fold) (13). For instance, an Indian report revealed conjunctival squamous neoplasia (CSN), particularly the invasive form, to be in 78.26% of those with HIV infection (1). The higher prevalence tends to be common in communities with poor healthcare including low immunization (14) (15). Rampant CSN risk factors in Africa include; prolonged solar radiation exposure, HIV infection, increased p53 expression and Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) infection (16). In Uganda, popular risk factors comprise of prolonged exposure to sun rays, HIV immunosuppression, and poverty (14).

Wide surgical excision using the "no touch" approach (Shields) and further cryotherapy have been the usual treatments for OSSN. However, nonsurgical therapy with topical chemotherapeutic drugs has emerged as the preferred option for managing OSSN due to high recurrence rates ranging from 5% to 66% after surgical (17) (18). The general predictors of poor prognosis in OSSN include; invasion, recurrence, feeder vessel proliferation, positive resection margin, immunosuppression, histologic grade, and the young age of a patient (19).

Little is known about the clinic demographics and OSSN grades of these patients in a Ugandan context due to shifting patterns in the prevalence and treatment choices for the disease. In this article, we discuss the clinic demographic characteristics and OSSN scores of patients who have presented with this condition at a tertiary hospital.

Materials and method

Study design and site

We set out to study the burden of OSSN. This was a retrospective laboratory-based study at Mbarara of Science and Technology (MUST)/ Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital (MRRH) Pathology laboratory. The MUST Pathology department was established in 1995 and since then it has acted as the referral laboratory offering histology, cytology and autopsy services to MRRH. It handles approximately 3500 histology specimens and 1500 cytology specimens per year.

In its catchment area, which includes the following districts: Mbarara, Bushenyi, Ntungamo, Kiruhura, Ibanda, Buhweju, Rubirizi, Mitooma, Kazo, Rwampara, and Isingiro, the Mbarara regional referral hospital serves a population of more than four million people. The hospital also sees patients from the nearby nations of Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, as well as regional referral hospitals of Kabale, Masaka and Fort Portal. It offers specialist medical and surgical services including neurosurgery, urology, cardiothoracic surgery, general surgery, pediatrics, nephrology, oncology, dermatology, ophthalmology, radiology, ENT, psychiatry and intensive care services.

It was a retrospective investigation. We examined all patient files from the MUST/MRRH histopathology laboratory in South Western Uganda between January 2015 and October 2021 that contained a histological diagnosis of ocular surface squamous neoplasia. The following were recorded: Age, Sex and ocular squamous surface neoplasia (OSSN) histological grades. Age was further categorized in 15-year groups as 15-29 years, 30-44 years, 45-60 years and 61 years & above. OSSN histological grades was further categorized as Conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia I (CIN I) Conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia II (CIN II), Conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia III (CIN III) Carcinoma in situ (CIS) and invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

Data analysis

The data was sorted in Microsoft Excel 2019 and exported to IBM SPSS version 28.0.0.0 for analyses. Continuous variables were analyzed by mean, median, and standard deviation. Categorical variables were analyzed as proportions. The output was presented as tables and figures for easy comprehension. A statistically significant result was one with a p value lower than 0.05.

Results

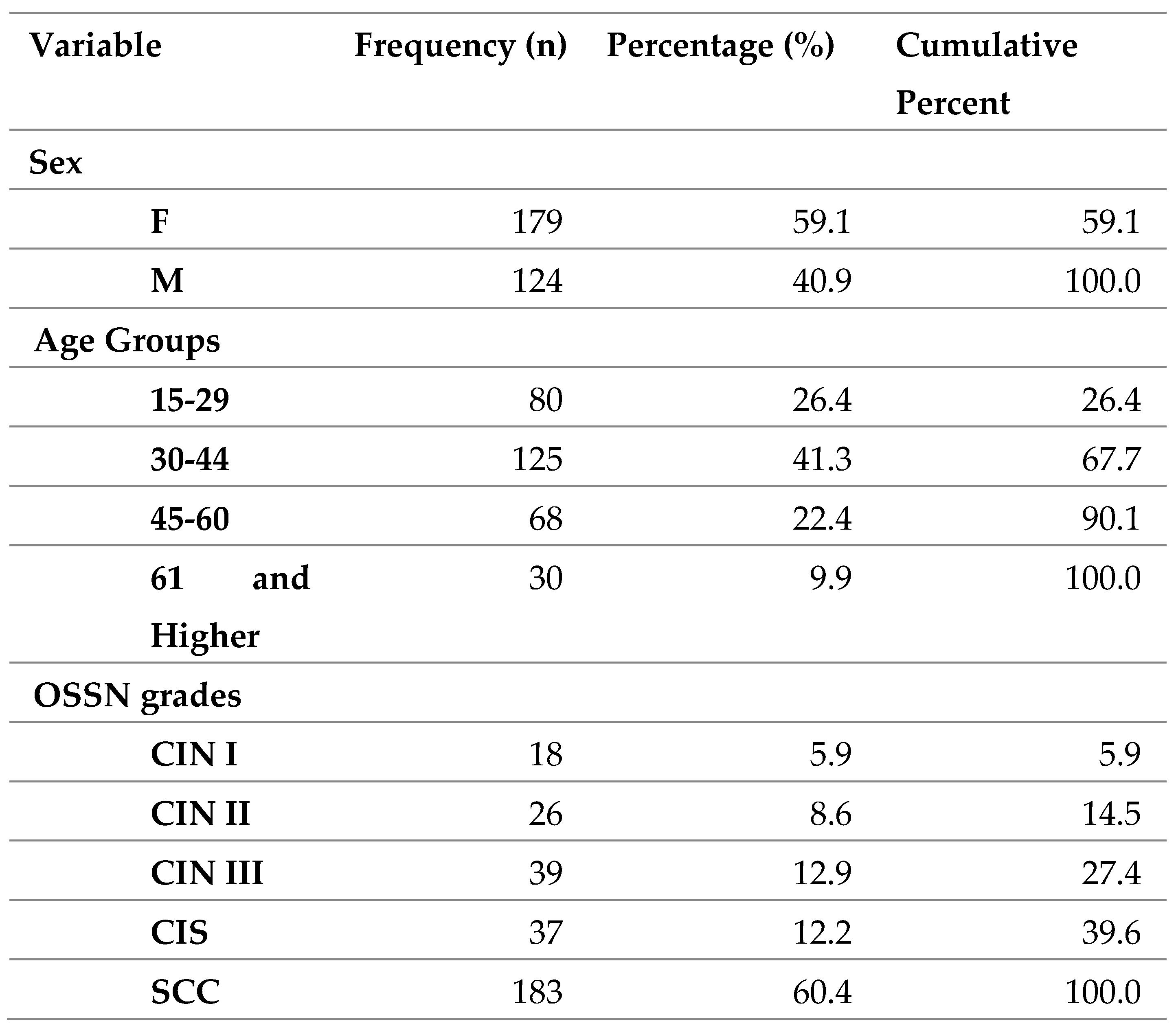

A total of 303 patient records were included. This contributed to 26.7% of all confirmed ocular lesions. The age range was 15-106 years and the mean age was 39.99 years (SD-14.702). The commonest age group was 30-44years (41.3%). 15- 29 composed of 26.4%, 45-60 composed of 22.4% and 61 & above composed of 9.9%. The females were more common (59.1%) than males (40.9%).

Table 1.

Frequency Statistics of patients, N = 303.

Table 1.

Frequency Statistics of patients, N = 303.

The commonest OSSN was invasive SCC (60.4%). Low grade dysplasia composed of (14.5%) while high grade dysplasia composed of 25.1%.

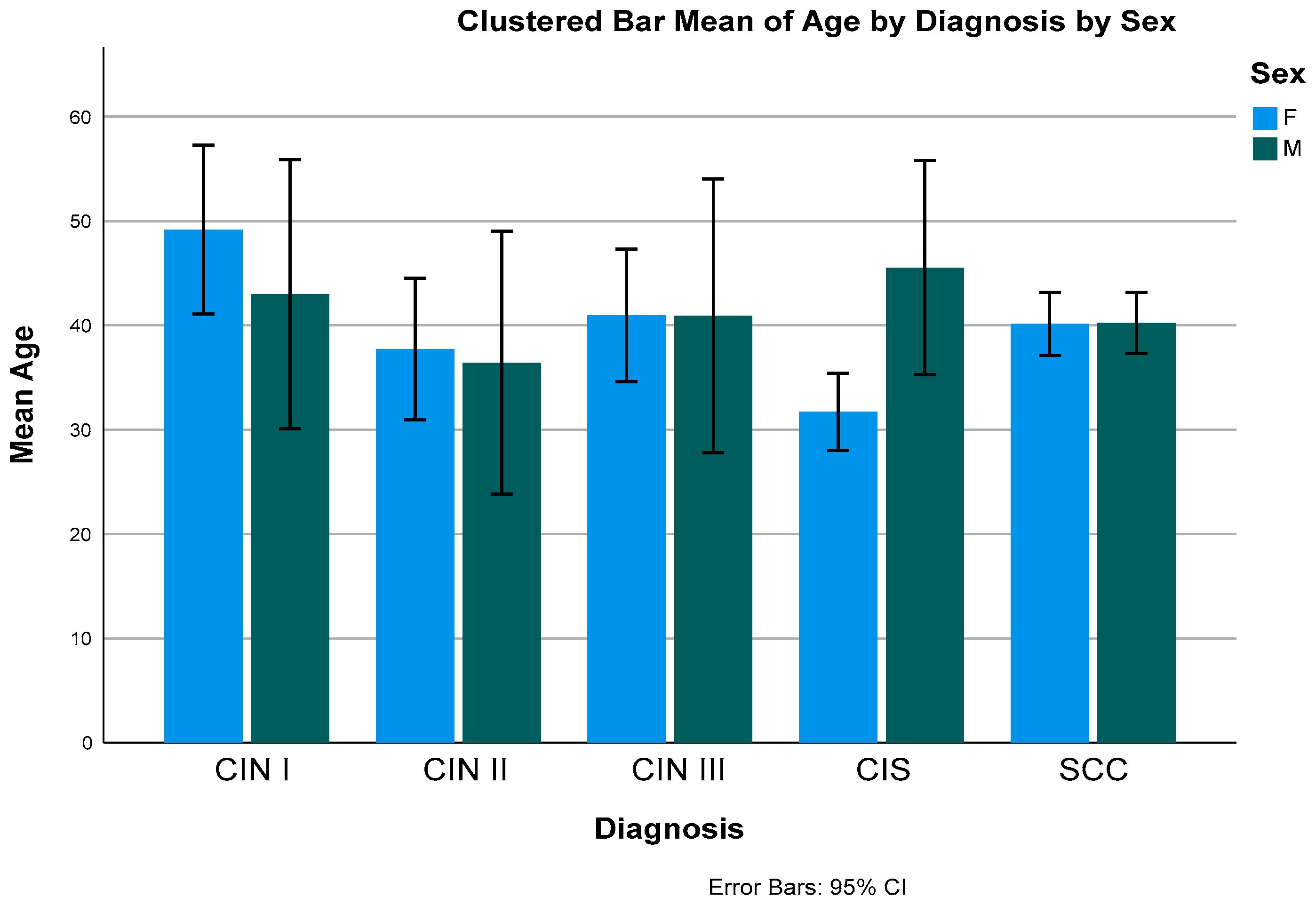

Figure 1.

Bar Graph showing the mean age distribution by diagnosis and sex.

Figure 1.

Bar Graph showing the mean age distribution by diagnosis and sex.

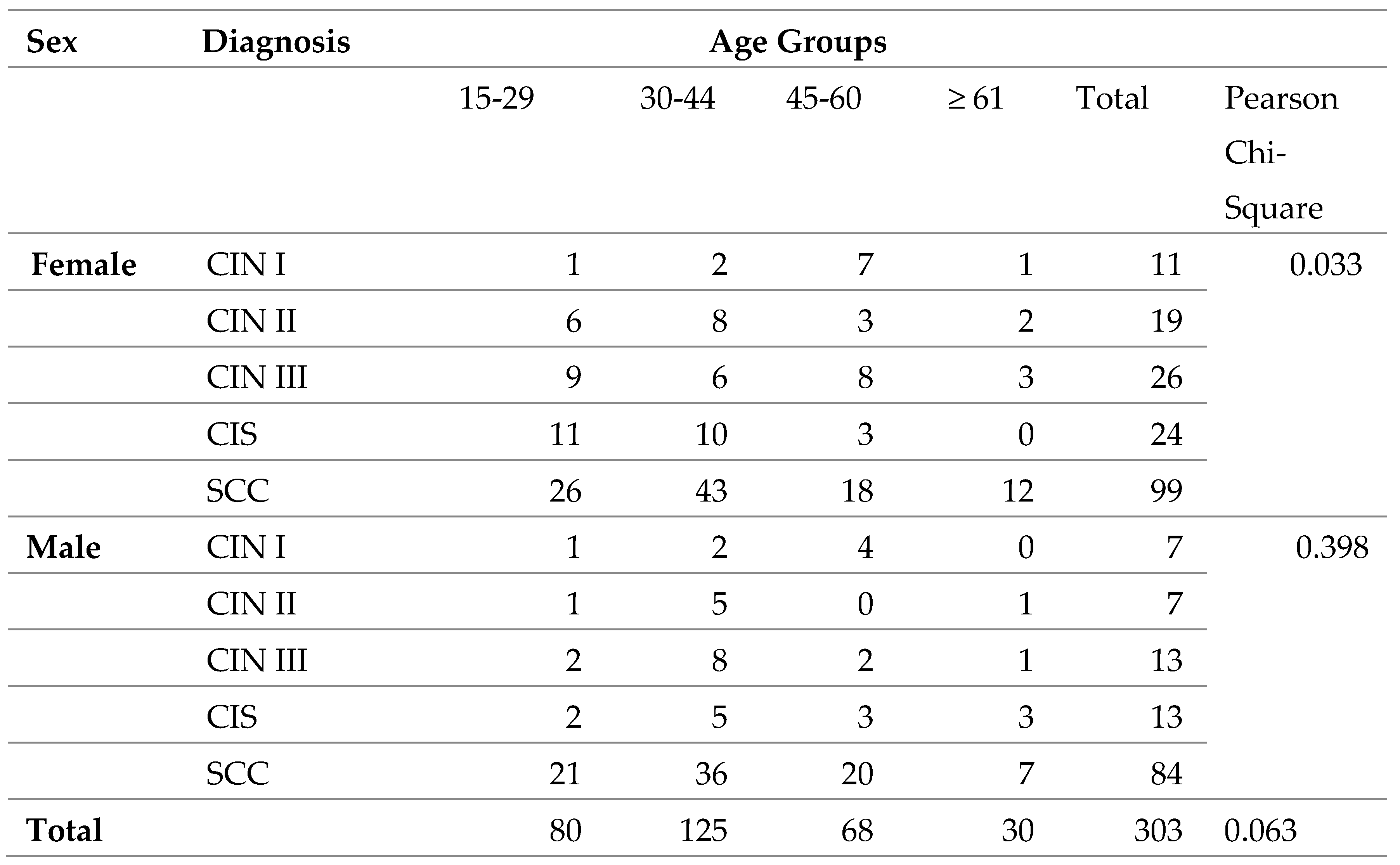

Generally, there is no association between OSSN and age groups, however when stratified with sex, there was an association with female sex (p-value- 0.033).

Table 2.

Cross-tabulation of OSSN grades and age groups by Sex, N=303.

Table 2.

Cross-tabulation of OSSN grades and age groups by Sex, N=303.

Discussion

In tropical nations, ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) is a prevalent lesion. Recent research from the developing world indicated that severe OSSN was the most prominent conjunctival lesion in need of disemboweling (19). Geographically, the incidence of IOSSN is the highest in countries near the equator and in the southern hemisphere, with peak incidence at a latitude of 16° South (5). The incidence decreases by half for each 10° increase in latitude, which has been attributed to reduced Ultra violet (UV) exposure (3) (20). In developed countries, patients with OSSN have a different disease profile and continue to present in elderly in both the general population (21).

Generally, the overall prevalence of OSSN in ocular lesions was 26.7%. This was much lower than the one reported in Kenya of 38% (22), however it is generally higher compared to many studies. This is could be attributed to the higher prevalence of Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and Human papilloma virus (HPV) infections in Uganda than surrounding countries in the region (23) (24).

In the current study, the mean age was reported to be 39.99 years. Identical results were observed in India (34 years) (19), in Malawi (35.8 years) (13), in India (40 years) (25) and in Botswana (38 years) (26). This could be attributed to the fact that most of the population in these places is young and that there is a high prevalence of HIV especially in the young population (25). Different findings have been reported in Australia (68.9 years) (27), in UK (71 years) (28), in Taiwan (63.4 years) (29). and in Turkey (63.7 years) (30). This elderly mean age is due to the fact it has been reported that these places have a reduced exposure to UV light as most of the work is indoors, and have reduced level of HIV and HPV exposure. A study done in Taiwan where the mean age was above 60 years revelated that none of the patients had HIV(29). This clearly indicates the role of HIV as a big risk factor for OSSN.

The commonest age group in our study was 30-44 years which is consistent with many African studies(14) (5) (26). This is likely attributed to the early and prolonged exposure to UV light in their occupations, in addition to the high burden of HIV and HPV infections (22). The commonest age groups in Europe and US are much higher, usually after 60 years (28) (31). This is attributed to accumulation of other driver mutations in these patients, not necessarily those caused by HPV and UV light.

In the current study, the incidence in females was higher (59.1%) than males. Studies conducted in Africa such as those in Botswana (53.9%) (26), in Kenya (65%) (22) and in Uganda (57%) are comparable to this (14). African women have increased risk probably due to their higher prevalence of HIV and HPV infections (5). This result contrasts many studies that reported a higher male prevalence(19), (32), (30). Higher incidence of OSSN in male gender is associated with increased exposure to ultraviolet rays during outdoor work (33), however may also be attributed to racial background, with males predominating in Caucasians (34) (32).

The most common grade of OSSN in our study was invasive SCC, with in-situ lesions less common. CIN I-5.9%, CIN II- 8.6, CIN III-12.9%, CIS-12.2 %, and invasive SCC (60.4%). These findings compare with studies done by several authors who reported that untreated OSSN usually shows ascending incidence with histologic grades (32). The prevalence of invasive SCC was also consistent with a study done in Pakistan (63.9%)(35) and in India (55%)(25). There has even been a higher prevalence of 70.7% a previous Ugandan study (6). Generally, our study's findings showed OSSN to be inclined towards advanced grades (high-grade CIN and invasive SCC) attributed to late diagnosis and lack of histopathology facilities or awareness (37). It can also be attributed to the poor treatment outcome and tumor recurrence in developing countries (38). It can also be attributed to the higher prevalence of HIV as seen in Uganda (39). Other counties have also reported invasive SCC as the commonest OSSN though at lower frequencies (28% in UK and 19.7% in Canada (36) (34). Much lower rates have been reported in the USA (11%) (31) and in New Zealand (9%) (27) because of having organized ophthalmic care services, most of which have been digitalized (40). A similar study done in Uganda reported CIN I to be 48 CIN II to be 66 CIN III to be 81 and 123 with invasive disease (14). This difference may be attributed to the different study design that Waddell et al, 2010 employed.

There was no clear explanation for the association between female gender with age groups and OSSN grades, however we postulate this could be explained by the high prevalence of HIV with a national prevalence of 6.8% compared to 3.9% for men (2020 Uganda HIV-AIDS fact sheet).

Conclusiona

This study confirms the high incidence of ocular surface squamous neoplasia among young individuals. Most of the ocular surface neoplasia is invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Most ocular surface neoplasia affects women in this region. It is necessary to conduct additional research to identify the risk factors for ocular surface neoplasia for patients in sub-Saharan Africa in order to avert acquisition of malignant forms of the disease.

Study Limitation

Due to the retrospective nature of this study where we reviewed records, we were unable to assess the impact of known risk factors such as Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Human Papilloma Virus infections on ocular surface neoplasia. We therefore recommend other studies to be done with higher forms of study.

Author Contributions

All authors agree to be accountable for the content of the work. RA: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, supervision, validation, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing. MY: conceptualization, data curation, histopathology slide interpretation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing – review & editing. AB: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, writing – review & editing. RK: formal analysis, writing-review & editing. DJR: conceptualization, data curation, histopathology slide interpretation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, writing – review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the publication of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was self-sponsored. The investigators collected the data, curated and analyzed it from the histopathology archives.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this study is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the administrators of Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital and, Mbarara University of Science and Technology pathology laboratory who grated us permission to carry out this study on the patients archived records data.

Conflict of Interest

The study's authors affirm that there were no financial or commercial ties that might be viewed as having a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Dandala P, Malladi P, Kavitha. Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia (OSSN): A Retrospective Study. J Clin Diagn Res JCDR. 2015.

- Pola, E.C.; Masanganise, R.; Rusakaniko, S. The trend of ocular surface squamous neoplasia among ocular surface tumour biopsies submitted for histology from Sekuru Kaguvi Eye Unit, Harare between 1996 and 2000. Central Afr. J. Med. 2003, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Newton R, Ferlay J, Reeves G, Beral V, Parkin DM. Effect of ambient solar ultraviolet radiation on incidence of squamous-cell carcinoma of the eye. Lancet Lond Engl. 1996, 347, 1450–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields C, Chien J, Surakiatchanukul T, Sioufi K, Lally S, Shields J. Conjunctival Tumors:Review of Clinical Features, Risks, Biomarkers, and Outcomes. Asia-Pac J Ophthalmol. 2017, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Gichuhi, S.; Sagoo, M.S.; Weiss, H.A.; Burton, M.J. Epidemiology of ocular surface squamous neoplasia in Africa. Trop. Med. Int. Heal. 2013, 18, 1424–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ateenyi-Agaba, C. Conjunctival squamous-cell carcinoma associated with HIV infection in Kampala, Uganda. Lancet 1995, 345, 695–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, M.S.A.; Dareshani, S.; Ali, M.A.; Khan, M.S. Squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva: analysis of fifteen cases. J. Ayub Med Coll. Abbottabad : JAMC 2010, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Hämmerl, L.; Ferlay, J.; Borok, M.; Carrilho, C.; Parkin, D.M. The burden of squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva in Africa. Cancer Epidemiology 2019, 61, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porges, Y.; Groisman, G.M. Prevalence of HIV With Conjunctival Squamous Cell Neoplasia in an African Provincial Hospital. Cornea 2003, 22, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurnani B, Kaur K. Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 [cited 2022 ]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK573082/. 29 May.

- Edge, S.; Byrd, D.; Compton, C.; Fritz, A.; Greene, F.; Trotti, A. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal, R.; Rath, S.; Vemuganti, G.K. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia – Review of etio-pathogenesis and an update on clinico-pathological diagnosis. Saudi J. Ophthalmol. 2013, 27, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiong, T.; Borooah, S.; Msosa, J.; Dean, W.; Smith, C.; Kambewa, E.; Kiire, C.; Zondervan, M.; Aspinall, P.; Dhillon, B. Clinicopathological review of ocular surface squamous neoplasia in Malawi. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2013, 97, 961–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waddell, K.; Kwehangana, J.; Johnston, W.T.; Lucas, S.; Newton, R. A case-control study of ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) in Uganda. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 127, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oellers, P.; Karp, C.L.; Sheth, A.; Kao, A.A.; Abdelaziz, A.; Matthews, J.L.; Dubovy, S.R.; Galor, A. Prevalence, Treatment, and Outcomes of Coexistent Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia and Pterygium. Ophthalmology 2012, 120, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Kiire, C.; Dhillon, B. The aetiology and associations of conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2006, 90, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabin, G.; Levin, S.; Snibson, G.; Loughnan, M.; Taylor, H. Late Recurrences and the Necessity for Long-term Follow-up in Corneal and Conjunctival Intraepithelial Neoplasia. Ophthalmology 1997, 104, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanji, A.A.; Sayyad, F.E.; Karp, C.L. Topical chemotherapy for ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2013, 24, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meel, R.; Dhiman, R.; Vanathi, M.; Pushker, N.; Tandon, R.; Devi, S. Clinicodemographic profile and treatment outcome in patients of ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 65, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun EC, Fears TR, Goedert JJ. Epidemiology of squamous cell conjunctival cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol. 1997 Feb;6(2):73–7.

- A Lee, G.; Hirst, L.W. Retrospective study of ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Aust. New Zealand J. Ophthalmol. 1997, 25, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gichuhi, S.; Macharia, E.; Kabiru, J.; Zindamoyen, A.M.; Rono, H.; Ollando, E.; Wanyonyi, L.; Wachira, J.; Munene, R.; Onyuma, T.; et al. Clinical Presentation of Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia in Kenya. JAMA Ophthalmol 2015, 133, 1305–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimanga DO, Ogola S, Umuro M, Ng’ang’a A, Kimondo L, Murithi P, et al. Prevalence and Incidence of HIV Infection, Trends, and Risk Factors Among Persons Aged 15–64 Years in Kenya: Results From a Nationally Representative Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2014 ;66(Suppl 1):S13–26. 1 May.

- Vithalani, J.; Herreros-Villanueva, M. HIV Epidemiology in Uganda: survey based on age, gender, number of sexual partners and frequency of testing. Afr. Heal. Sci. 2018, 18, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaliki, S.; Kamal, S.; Fatima, S. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia as the initial presenting sign of human immunodeficiency virus infection in 60 Asian Indian patients. Int. Ophthalmol. 2016, 37, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, K.T.; Steenhoff, A.P.; Bisson, G.P.; Nkomazana, O. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia among HIV-infected patients in Botswana. South Afr. Med J. 2015, 105, 379–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, R.R.; McKelvie, J. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia in New Zealand: a ten-year review of incidence in the Waikato region. Eye 2021, 36, 1567–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousef, Y.A.; Finger, P.T. Squamous Carcinoma and Dysplasia of the Conjunctiva and Cornea: An Analysis of 101 Cases. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, I.-H.; Hu, F.-R.; Wang, I.-J.; Chen, W.-L.; Hsu, Y.-J.; Chu, H.-S.; Yuan, C.-T.; Hou, Y.-C. Clinicopathologic correlation of ocular surface squamous neoplasia from a university hospital in North Taiwan 1994 to 2014. J. Formos. Med Assoc. 2018, 118, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzayev, I.; Gündüz, A.K.; Gündüz. .; Ateş, F.S..; Baytaroğlu, H.N. Demographic and clinical features of conjunctival tumours at a tertiary care centre. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2021, 105, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, A.A.; Galor, A.; Karp, C.L.; Abdelaziz, A.; Feuer, W.J.; Dubovy, S.R. Clinicopathologic Correlation of Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasms at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute: 2001 to 2010. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 1773–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellerive, C.; Berry, J.L.; Polski, A.; Singh, A.D. Conjunctival Squamous Neoplasia: Staging and Initial Treatment. Cornea 2018, 37, 1287–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, U.; Karp, C.L.; Dubovy, S.R. Update on the Management of Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia. Curr. Ophthalmol. Rep. 2021, 9, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiire, C.A.; Stewart, R.M.K.; Srinivasan, S.; Heimann, H.; Kaye, S.B.; Dhillon, B. A prospective study of the incidence, associations and outcomes of ocular surface squamous neoplasia in the United Kingdom. Eye 2018, 33, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babar, T.F.; Khan, M.N.; Hussain, M.; Shah, S.A. Spectrum of ocular surface squamous neoplasia. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2007, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Ogun, G.O.; Ogun, O.A.; Bekibele, C.O.; Akang, E.E. Intraepithelial and invasive squamous neoplasms of the conjunctiva in Ibadan, Nigeria: a clinicopathological study of 46 cases. Int. Ophthalmol. 2008, 29, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waddell, K.M.; Downing, R.G.; Lucas, S.B.; Newton, R. Corneo-conjunctival carcinoma in Uganda. Eye 2006, 20, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arunga, S.; Lloyd, H.-W.C.M.; Twinamasiko, A.; Frederick, M.; Onyango, J. Predictors of ocular surface squamous neoplasia and conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma among ugandan patients: A hospital-based study. Middle East Afr. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 25, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, L.F.d.A.; Fernandes, B.F.; Burnier, J.V.; Zoroquiain, P.; Eskenazi, D.T.; Jr, M.N.B. Incidence of epithelial lesions of the conjunctiva in a review of 12,102 specimens in Canada (Quebec). Arq. Bras. de Oftalmol. 2011, 74, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borooah, S.; Grant, B.; Blaikie, A.; Styles, C.; Sutherland, S.; Forrest, G.; Curry, P.; Legg, J.; Walker, A.; Sanders, R. Using electronic referral with digital imaging between primary and secondary ophthalmic services: a long term prospective analysis of regional service redesign. Eye 2012, 27, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).