1. Introduction

Lizards are classified as ectothermic and depend on external sources for heat gain. They can generate metabolic heat, but it is at a very low level and is usually lost quickly [

1]. Lizards can control their body temperatures by using various behavioral patterns [

2], and basking is usually the preferred one [

1].

As winter approaches in temperate zones and temperatures drop below the critical minimum, most species of lizards enter into hibernation. They retreat into suitable hibernacula where temperatures remain higher during winter [

1]. Reptiles in Bulgaria, including lizards hibernate from late autumn to early spring. Yet, individuals of many species have been found active during this period. Most of the observations have been made in the warmest parts of the country and in places with favorable microclimatic conditions [

3].

Three species of lizards of the genus

Podarcis occur in Bulgaria. Two of them – the Common Wall Lizard,

P. muralis (Laurenti, 1768) and the Erhard`s Wall Lizard,

P. erhardii (Bedriaga, 1876) – have similar habitat preferences. They inhabit mainly rocky outcrops and hide in the crevices but do not normally coexist in the country.

Podarcis muralis is widespread and occurs up to 2150 m a.s.l. The distribution of

P. erhardii is limited to some southern parts of Bulgaria where it occurs up to 1600 m a.s.l. [

4,

5].

Podarcis muralis has been recorded in various natural or man-made habitats in several cities in Bulgaria – Ruse [

6], Plovdiv [

7], Blagoevgrad [

8,

9], Sofia [

10], Stara Zagora [

11]. Information on individuals of

P. erhardii in the periphery and surroundings of the city of Blagoevgrad was published by Pulev & Sakelarieva [

8,

9].

The two species occupy different areas in the city of Blagoevgrad.

Podarcis muralis is found in densely or sparsely populated built-up areas and along the Blagoevgradska Bistritsa River.

Podarcis erhardii, on the other hand, inhabits sparsely populated built-up areas and the territory of the Loven dom Park and the Zoo [

8,

9], unpublished data.

The period of activity of both species is from March to October [

5]. Despite that individuals of

P. muralis [

3,

6,

12,

13,

14] and

P. erhardii [

3,

12,

13] can be found in the country during winter season when the weather is sunny and warm. More specific data were published by Buresch & Zonkow [

15] (16.02.1925, near Dolna Beshovitsa), Undjian [

6] (31.01.1960, Varna region), and Westerstrom [

16] (27.12.2000, Godech surroundings) for

P. muralis and by Buresch & Zonkow [

15] (12.02.1928, Kardzhali surroundings), Pulev & Sakelarieva [

8] (06.02.2004, Blagoevgrad surroundings), Grozdanov et al. [

17] (28.12.2015, 21.02.2015, near Rakitna), Malakova et al. [

18] (14.12.2017, N/NW of Tserovo) for

P. erhardii.

Although there were records of winter activity of P. muralis and P. erhardii in Bulgaria, this behavior has not been studied in detail. The purpose of this research was to observe and analyze the winter activity of these two species of lizards in the city of Blagoevgrad.

2. Materials and Methods

The climatic conditions in winter in the region of the city of Blagoevgrad are characterized by positive average monthly temperatures in all months (December, January, and February), with an average seasonal temperature of 2.4°C in the period 1991–2020 [

19]. For the first time, active individuals of

P. erhardii were found by chance during a walk in the city outskirts in December 2015. The study on the winter activity of

P. muralis and

P. erhardii was conducted during the winter months in the period 2015–2017.

The two winter seasons differed significantly in their thermal characteristics. The average temperature in the winter of 2015–2016 was 4.2°C (or 1.8°C above the climatic norm). Normal temperature values were recorded in December and January and abnormally high temperatures – 9.3°С, in February. The average winter temperature in 2016–2017 was 0.7°C, which was 1.7°C below the climatic norm. December and January were cold with temperatures significantly lower than the norm (for January by 4.9°C), while February was warmer (5.5°C) [

19].

The observations were carried out at two different sites in different days with high solar radiation. Each observation lasted for 30 minutes during the warmest part of the day – at site 1 from 12:30 p.m. to 4:45 p.m. and at site 2 from 11:50 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. Only once site 1 was visited twice in a day. Site 1 is a typical urban territory, located in the densely populated built-up area of the city of Blagoevgrad [see 9]. It was inhabited only by P. muralis. The habitat is a vertical stone wall with a height of about 120 cm and a length of 180 m with southwest exposure and an altitude of about 360 m. The lizards hibernate in the crevices of the stone wall and bask on it. There are buildings and a paved area behind the wall, and railway tracks and gravel in front of it. This site was visited 50 times in 49 days: 18 times in 2015–2016 and 32 times in 2016–2017.

Site 2 is located in the territory of the Loven dom Park and the Zoo see [

9]. It is a suburban area, inhabited only by

P. erhardii. The habitat is a rock scarp with a height of 3–5 meters and a length of 160 m with south, southwest, and southeast exposition and 70–80 degree inclination. The altitude is approximately 600 m. The lizards hibernate in the crevices and bask on the rock. There is an artificial pine forest above the scarp and stones, grasses, bushes and asphalt road in front of it. The site was visited 48 times in 48 days: 16 times in 2015–2016 and 32 times in 2016–2017.

The following parameters were recorded during the study: date and time of observation, number of specimens observed, age groups (adults, subadults, and juveniles), behavior, environmental conditions, minimum night/morning air temperature measured in the day of observation, air and substrate temperatures measured during the observation. The air temperatures were measured with a temperature sensor Greisinger – EASYlog24RFT. An infrared thermometer UT303D was used to record the substrate temperature. All temperature values were rounded to half a degree (0.5°C).

3. Results

3.1. Podarcis muralis

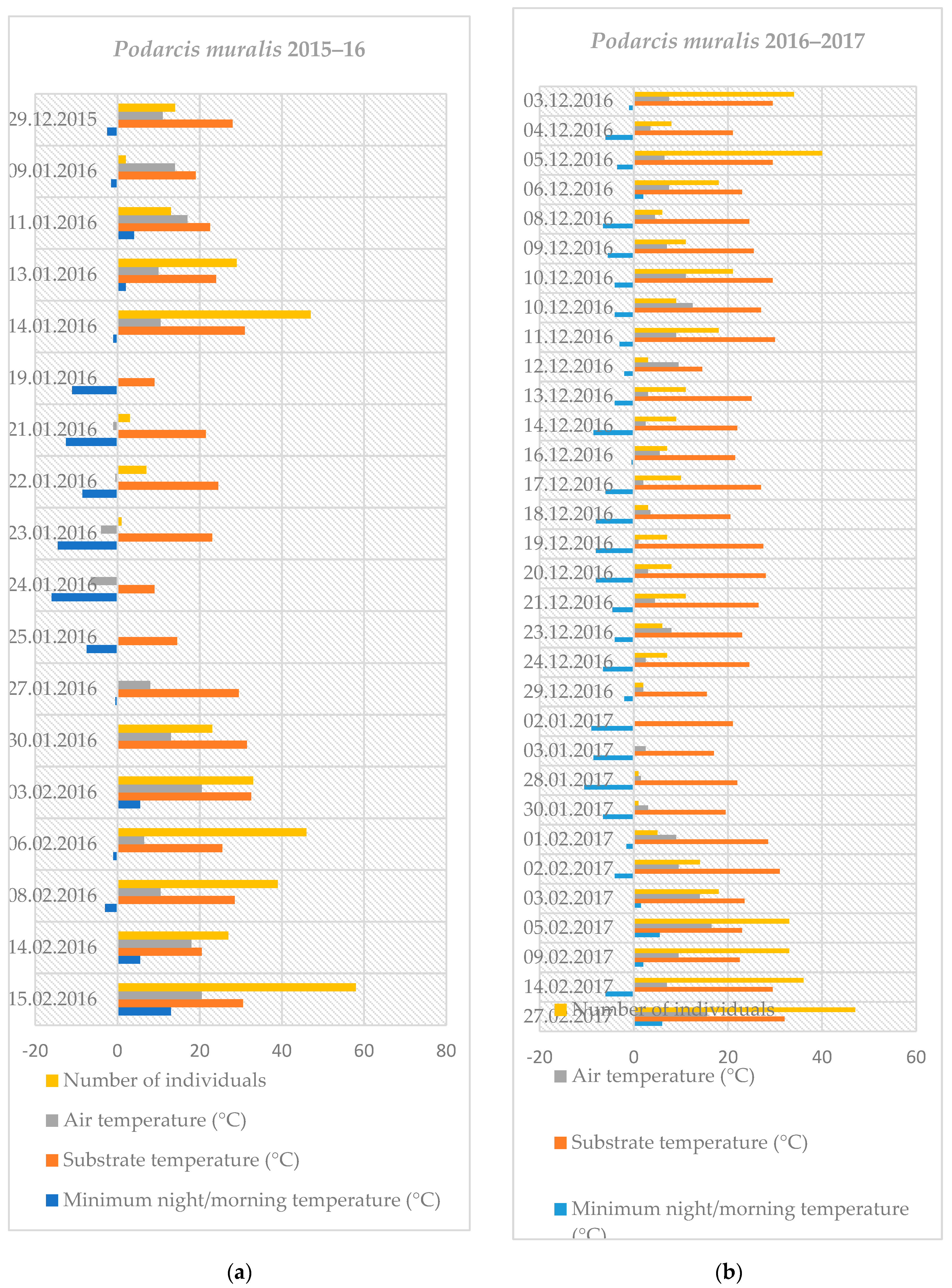

A total of 779 active individuals were observed in study area (site) 1 during 44 out of 50 visits. The number of individuals recorded during 14 visits (out of 18) in 2015−2016 was 342 − 14 in December during 1 visit, 125 in January during 8 visits (out of 12), and 203 in February during 5 visits (

Figure 1a and

Figure 2,

Table S1). In 2016−2017, 437 individuals were observed during 30 visits (out of 32) − 249 in December during 21 visits, 2 in January during 2 visits (out of 4), and 186 in February during 7 visits (

Figure 1b,

Table S1). The maximum number of active individuals was recorded at the end of both winters – 58 on 15 February 2016 and 47 on 27 February 2017. Only one individual was observed three times, shortly after the middle of the winter seasons − on 23 January 2016 and on 28 and 30 January 2017.

The mean number of the individuals registered in both winter seasons was 17.70 ± 15.32 (range 1–58) − 22.8 ± 18.95 in 2015–2016 and 14.56 ± 12.73 in 2016–2017. No lizards were observed in 6 out of 50 times (or in 12% of the visits) when the study area was visited – 4 times in January 2016 and 2 times in January 2017. The adults were most often present – in 41 of the cases, followed by the subadults – in 36 cases, and the juveniles – in 35 cases. Representatives of all age groups were registered in 33 out of 44 cases (or 75%).

Basking was the predominant behavior observed. In fact, it was exhibited in all 44 cases when active lizards were recorded. Basking was the only behavior observed in 25 of the cases, and some individuals also exhibited locomotor activity in the remaining 19 cases. Lizards flattened their bodies dorsoventrally while basking in 47 of the 48 times (or 97.91%) when active specimens were observed.

Active individuals were mostly observed in sunny days without wind – in 30 cases, followed by sunny days with slight, moderate, or strong wind – in 11 cases, and most rarely in partly cloudy weather – in three cases. On the six occasions when no lizards were recorded, the weather was sunny with no wind on five occasions, and partly cloudy on one occasion. Individuals were registered in a wide range of air temperatures measured during the observation: from -4 to +20.5°C, and mean air temperature of +7.9°C ± 5.81. However, individuals were only observed at positive substrate temperatures: from +14.5 to +32.5°C, with a mean value of +25.2°C ± 4.34.

The mean air temperature when no lizards were found was +0.7°C ± 4.68 (range from -6.5 to +8°C) and the mean substrate temperature was +16.7°C ± 7.82 (range from +9 to +29.5°C). The mean night/morning air temperature before visiting the study area during the day at which no lizards were registered was -8.8°C ± 5.04 (range from -16 to -0.5°C).

3.2. Podarcis erhardii

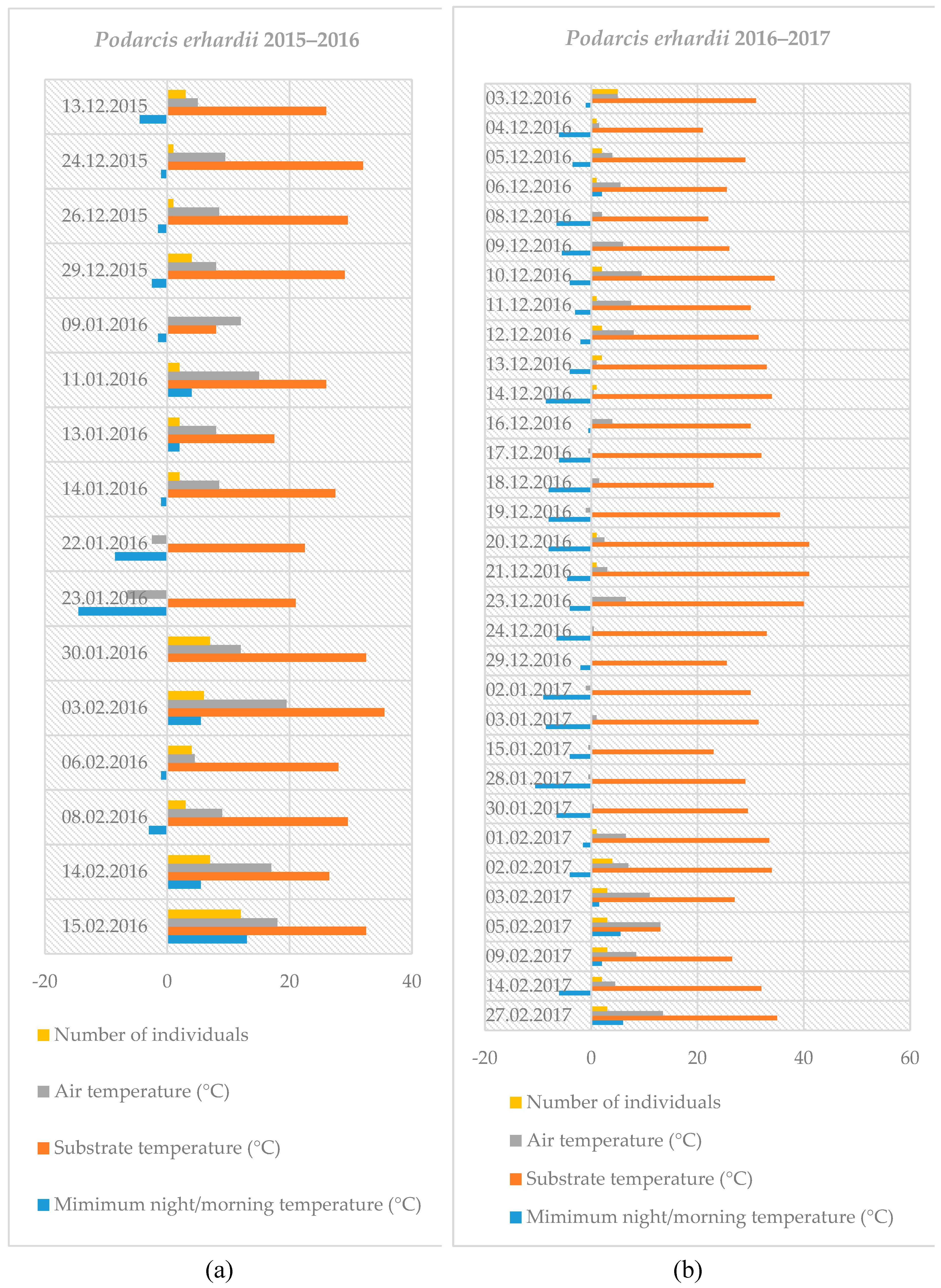

Altogether 92 active individuals were observed in study area 2 during 31 out of 48 visits. The number of individuals recorded during 13 visits (out of 16) in 2015−2016 was 54 − 9 in December during 4 visits, 13 in January during 4 visits (out of 7) and 32 in February during 5 visits (

Figure 3a and

Figure 4,

Table S2). In 2016−2017, 38 individuals were observed during 18 visits (out of 32) − 19 in December during 11 visits (out of 20), 0 in January during 5 visits, and 19 in February during 7 visits (

Figure 3b,

Table S2). The maximum number of active individuals was recorded at the end of the first and the beginning of the second winter – 12 individuals on 15 February 2016, and 5 on 3 December 2016, respectively. In many cases, only one individual was observed, mainly in December, i.e. in the beginning of winter.

The mean number of the individuals recorded in both winter seasons was 2.96 ± 2.40 (range 1–12) − 4.15 ± 3.13 in 2015–2016 and 2.1 ± 1.18 in 2016–2017. No lizards were found in 17 out of 48 times (or 35%) when the study area was visited – 3 times in January 2016, 9 times in December 2016, and 5 times in January 2017. Adult individuals were observed in all the cases when some activity was registered. The subadults and juveniles were recorded five times each. Representatives of all age groups were registered only once or in 3.2% of the cases when active individuals were observed. Only adults were registered in 22 out of 31 visits.

As in the other species, basking was the main behavior observed. It was the only behavior exhibited in 18 out of 31 cases when active lizards were recorded. In other five cases, some individuals exhibited locomotor activity as well, and in four other cases, only locomotor activity was demonstrated. Fight between two males was observed four times when the number of the active individuals was 4 or more. Only two individuals were observed to flatten their bodies dorsoventrally on two different occasions.

Active specimens were mostly registered in sunny days without wind – in 23 cases, followed by sunny days with slight or moderate wind – in 6 cases, and most rarely in partly cloudy weather – in 2 cases. During the 17 visits when no lizards were observed, the weather was sunny with no wind – on 14 occasions, partly cloudy – on 2 occasions, and cloudy – on 1 occasion.

Individuals were recorded in a wide range of air temperatures: from +0.5 to +19.5°C, and the mean air temperature was +8.2°C ± 4.89. They were also observed in a wide range of substrate temperatures: between +13 and +41°C, and a mean substrate temperature of +29.8°C ± 5.82. The mean night/morning air temperature recorded before visiting the study area during the day was -0.9°C ± 4.64 (range from -8.5 to +13°C).

The mean air temperature when no lizards were found was +1.3°C ± 4.1 (range from -6.5 to +12°C) and the mean substrate temperature was +27.1°C ± 7.19 (range from +8 to +40°C). The mean night/morning temperature recorded before visiting the study area during the day when no lizards were registered was -6.5°C ± 3.47 (range from -14.5 to +0.5°C).

4. Discussion

Cities and suburbs offer many suitable habitats for

P. muralis. According to Bády & Vagi [

20], the species is the most abundant reptile in the urban environments of Hungary. The winter above-ground activity of the Common Wall Lizard in an urban habitat was studied by

Rugiero [

21]

who reported that active lizards were found in all of the sampling dates and their activity was rather regular. Bády & Vagi [

20] compared the activity, thermoregulatory behavior, and thermal environment of the species in an urban and a close-to-natural habitat during spring, summer, and autumn. Falaschi [

22] evaluated the effects of temperature, precipitation, wind, humidity, and phenology on the detection probability of the Common Wall Lizard in a residential area in northern Italy from 12 April to 6 October 2020. He concluded that temperature and phenology are the most influential drivers of detecting probability, which was the highest earlier in the active season (April) and between 24 and 28 degrees decreasing at lower or higher temperatures.

The number of individuals of the Common Wall Lizard recorded in both winter seasons was about 8.5 times that of the Erhard`s Wall Lizard. On the one hand, the population of

P. muralis was much more abundant and with higher density, since the habitat in which it lives (a stone wall) provides better conditions, in particular, more crevices for shelter and hibernation. According to Bády & Vagi [

20], the population density of the Common Wall Lizard in an urban habitat is also affected by thermal factors, better food supply, or fewer competitors and predators.

On the other hand,

P. erhardii is more thermophilic species than

P. muralis. This is also confirmed by the values of the air and substrate temperatures, the mean ones as well as those measured at the time of observations. According to Catsadorakis [

2], who observed a population of the species on the island of Nexus in spring (March and April) and summer (August), the activity of the lizards of

P. erhardii was correlated with ambient temperatures (mean, min, max) in spring and it was strongly correlated with mean air temperature in sun, up to 30–32.5°C.

In this study, the mean air temperature (+8.2°C) was with 0.3°C higher than the one at which individuals of

P. muralis were observed. No active individuals of the Erhard`s Wall Lizard were recorded at negative air temperatures in the two winters. At the same time, several individuals of

P. muralis (10 adults, and 1 subadult) were registered active, basking at negative air temperatures in the beginning of the third decade of January 2016 (

Table S1 and S2).

The values of minimum air temperatures at which both species were observed, -4°C for

P. muralis, and +0.5°C for

P. erhardii are much lower if compared to the values reported in other publications: 15°C [

16] and about 12°C [

13,

14] for

P. muralis and about 15°C [

8] and 15.7°C [

18] for

P. erhardii.

All individuals of the two species were observed only at positive substrate temperatures. Probably, the substrate temperature values are more important for the winter activity of petrophilic species than the air temperatures. The warming of the substrate depends on the amount of absorbed total solar radiation. Thus, the temperature of the substrate is determined by the intensity of the solar radiation, the altitude, the exposition, the inclination, the composition, and the color of the rocks. When Strijbosch et al. [

23] studied the distribution and ecology of lizards in the Greek province of Evros in September–October 1983 and March–July 1984, they concluded that the activity patterns of all species (including

P. muralis and

P. erhardii) were strongly influenced by exposition and altitude. The activity occurs earlier on southern slopes than on northern ones and at lower altitudes than higher ones.

For the conditions of Bulgaria, the amounts of solar radiation received on southern slopes can exceed the radiation on slopes with northern exposition by several times [

24]. Although study area 2 was at a higher altitude (more than 200 m), the rocks there received larger amounts of solar radiation (i.e. were warmer). They had south exposition and suitable inclination, so the sun's rays fell almost perpendicularly, compared to the stone wall at study area 1, which faced southwest and the sun's rays fell at a smaller angle. As a result, the temperatures of the substrate at habitat 2 were higher. Despite the higher altitude, the mean and maximum values when individuals of

P. erhardii were observed were higher with 4.6 and 8.5 degrees, respectively, if compared to the values for

P. muralis.

Solar radiation is a major factor in climate formation. In Bulgaria, the total solar radiation (direct and diffuse) is the lowest in December and January and the lowest temperatures were measured in January [

25,

26]. Accordingly, the smallest number of individuals of both studied species were registered in January, almost all of them in January 2016. Large amplitudes in average temperatures were observed then. A short-term cold was registered at the beginning of the month and a more significant one from 16 to 25 January, when a minimum temperature of -16.4°C was measured. There were also sunny days with positive temperatures when the lizards were observed. January 2017 was especially cold. A minimum temperature of -19.0°C was recorded in the city of Blagoevgrad, and a temperature of -22.5°C was measured in the conditions of a more pronounced temperature inversion in the surroundings [

27]. Actually, no individuals of

P. erhardii were observed in January 2017 and only 2 individuals of

P. muralis were registered at the very end of the month (

Table S1 and S2).

The greatest number of individuals of both species were recorded in February – the half of all Common Wall Lizard individuals (398) and more than the half of the Erhard's Wall Lizard individuals observed during the two winter seasons (51). Most of them were registered in February 2016, when almost all days were with temperatures above the norm, and the positive temperature anomaly reached 6.3°C. There was not a single day with a negative average daily temperature [

27], and the maximum temperature recorded at the Blagoevgrad hydro-meteorological station reached 22.8°C [

19].

Lizards are effective heliothermic thermoregulators, which prefer sunny, open surfaces [

20]. Their activity patterns are determined by climate and weather, and particularly by the levels of sunlight [

28]. They warm their bodies mainly by basking in the sun (absorbing solar radiation), but also indirectly from the surrounding substrate [

1].

Podarcis muralis is morphologically adapted to a rock-dwelling life [

29]. Body flattening is a behavioral adaptation of the Common Wall Lizard to absorb more solar radiation at lower temperatures. The dark color of the body (especially on both sides – up to black) also increases absorption. The Erhard's Wall Lizard probably relies more on indirect heat gain and that is why it prefers warmer substrates in winter. The main behavior was basking, but other activities such as locomotion and fighting (only for

P. erhardii) were also recorded. Such behavior was also reported by

Rugiero [

21].

The lizards of

P. muralis tended to aggregate. Clusters (several individuals together) were observed. This can be explained by the narrow time range of activity, the sunbathing around the hibernaculum (they did not disperse), the higher population density, and the biological features of the species. On the contrary,

P. erhardii was more aggressive, and fights between two males were observed. Usually, the individuals of the Erhard's Wall Lizard avoided each other unless they were a pair. This intraspecific aggression seems to be normal for the species [

30].