1. Introduction

In the public, both lay, professional and scientific, there is a widespread belief about the constant increase in occurence and increasingly serious consequences of student delinquency. This belief was largely created under the influence of the media, which often present data which are not based on evidence [

1] or enormous media reporting [

2], which contributes to the creation of the public belief that violence in schools happens every day.

As a result, social efforts to improve safety in schools have intensified [

3], by creating various “zero tolerance” safety policies that require suspension of students or their expulsion from school for committed offenses [

2], implementation of preventive programs, covering the school premises with security cameras [

4,

5]. One of the most extensive measures is the increasing presence of the police in schools [

6,

7]. It is estimated that by 2018, 61% of public schools in the USA (including 84% of public high schools) employed at least one security guard, most commonly School Resource Officers (SROs), or another law enforcement officer [

6]. From 1996 to 2016, the US Office of Community Oriented Policing allocated funds for about 7,000 SROs, not including other police officers working in schools without being classified as SROs [

7]. The presence of police officers in schools has been increasing ever since, despite a growing body of research evidence that questions their effectiveness, i.e. their effectiveness has not been scientifically supported [

6,

8].

The mass shooting that took place on 05/03/2023 in the elementary school “Vladislav Ribnikar” in Belgrade, in which eight children and a security guard were killed, while six children and one schoolteacher were wounded, shocked the public of Serbia [

9]. The shock was caused by the fact that this was the first mass murder in Serbian schools, and an even greater shock was caused by the information that the perpetrator of this massacre was a thirteen–year–old student of the said school.

Greater police presence in schools can be ensured by occasional or permanent police presence in schools, through various police programs. Special police officers, who participate in these programs, have different titles and perform different security tasks to some extent, but they are primarily responsible for the safety of children in schools. The most famous and most extensive such program in the world is School Resource Officers (SRO) – USA [

10], and the program with the same name is widespread in Canada [

11] as well. There are similar programs in Great Britain called Safer School Partnerships (SSP) [

12], in Turkey – School police project [

13], in South Korea – Korean School Police Officers (KSPOs) [

14]. In Croatia, the permanent presence of the police is ensured by the position of a contact police officer [

15]; while in Serbia, the permanent presence of the police in schools has been ensured since 2002, through the “School Police Officer” program [

8].

The introduction should briefly place the study in a broad context and highlight why it is important. It should define the purpose of the work and its significance. The current state of the research field should be carefully reviewed and key publications cited. Please highlight controversial and diverging hypotheses when necessary. Finally, briefly mention the main aim of the work and highlight the principal conclusions. As far as possible, please keep the introduction comprehensible to scientists outside your particular field of research. References should be numbered in order of appearance and indicated by a numeral or numerals in square brackets—e.g., [

1] or [

2,

3], or [

4,

5,

6]. See the end of the document for further details on references.

2. Literary review

All research related to police presence in schools could be systematized into three largest categories. The first and most numerous category of research is those that considered the role of the police in schools, i.e. tasks they perform. In the US, school police officers (SROs) are typically engaged in law enforcement, education, and mentoring (the triad model), with law enforcement being a major aspect of their role [

2,

16,

17], while education being the least important [

18]. Brown [

2] noted that many roles and tasks are imposed on SROs, and they are different depending on the state, police organization, funding entity, etc. Therefore, it is necessary to create a consensus of the entire community on defining the clear role and tasks of police officers in schools, while respecting certain specificities of individual environments [

7], such as the racial composition and grade level attending a certain school [

19].

In Canada (Ontario), researchers [

11] examined the views of school principals on the role of SROs and found that three important functions depend on the type of school, with SROs prioritizing teaching in elementary schools and law enforcement in high schools. Research from America also indicates that the way police officers are engaged in schools depends on the type of school [

20]. There principals expressed their views that police officers in schools with greater socio–educational challenges perform more of a law enforcement role, while in schools with less socio–educational deficiencies they perform more of an education–related role. In a study conducted in London high schools [

12], it was observed that police officers are positioned in schools with a high degree of student vulnerability, that is, they are deployed, similar to American schools, in parts of the city with the vulnerable population. The authors ask whether police officers in English schools protect students and prevent crime, or if they are a part of state surveillance that ‘socially sorts’ individuals who are ‘at risk’ and unlikely to become productive citizens. In a study conducted in the USA [

6], 119 SROs were interviewed and they declared that their roles are much broader than the classic triad model, i.e. they are closer to the three dimensions of community policing (community partnership, problem solving, organizational adaptation). In this respect, we should consider harmonizing the roles of school police officers in line with community policing. In a survey conducted in America [

21], SROs reported that in urban high schools they perform more conventional police roles (law enforcement), while SROs who supported community policing were more engaged in non–conventional roles, mentoring and education.

The second group of research related to one of the observed problems, which is the absence of specialized training for the actions of police officers in schools, or that the training is insufficient or inadequate [

8,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Martinez et al. [

25] found in their research that about 40% of SROs in Texas did not receive any specialized training for work in schools. Milojević et al. [

8] noted in their research that there is no specialized training for school police officers in Serbia. When it comes to police officers trained to work in schools, Bolger et al. [

22] indicated that officers who received formal SRO training preferred formal incident resolution, while more educated officers were more inclined to less punitive and informal responses to incidents. One of the perceived training gaps is that police officers receive minimal training on how to understand and interact with adolescents [

26]. Training for school police officers should also include topics such as behavior management, child development, communication techniques and disability awareness [

23]. Training that focuses on providing police officers with a better understanding of the developmental characteristics of children and youth can reduce instances where they overuse intense or harsh responses to typical behavior of children and youth, especially those with developmental disabilities [

10]. In accordance with the above, Trotman and Thomas [

24] noted that the role of the police in schools is changing, and therefore education and training of police officers should be adapted, in order to improve the set of different skills, which are not only required for law enforcement, but also for new roles of police officers. More attention should be paid to training in proactive techniques that can prevent certain provocative behaviors by using formal police procedures, from turning into more serious offenses, or even criminal acts [

10].

The greatest number of ambiguities remained with the third group of research that studied the presence of the police in schools and their effectiveness. A smaller number of studies have established the positive effects of the presence of the police in schools, i.e. that their presence reduces the fear of crime and increases the feeling of safety among students while they are at school [

8,

27,

28]. Theriot [

29] indicated that students who had a greater number of interactions (five or more) with SROs had more positive attitudes about SROs than those with fewer interactions. A number of studies have indicated that school employees, principals and teachers, have a positive opinion of the presence of SROs, believing that their presence deters students from misbehaving and contributes to reducing crime [

4,

13,

27,

28,

30]. Contrary to them, a number of studies indicate that the presence of police officers has no effect on safety in schools, and that they even have a negative effect on safety. Thus, research in Serbia [

8] indicates that since the introduction of the school police officer, the number of criminal acts and misdemeanors in schools has increased, which was also indicated in some research in the USA [

31,

32,

33,

34]. In a study in South Korea, researchers hypothesized that the presence of Korean School Police Officers (KSPO) might be associated with lower levels of delinquency in schools, but they found only limited evidence to support these assumptions [

14]. The researchers are of the opinion that the program can be considered partially effective. It will remain such until school police officers become a part of the school community for a longer period. Research in the USA [

35] indicated that the effect of the police presence in schools depends on the grade level and the type of crime or violence that the school encounters. For example, the police presence was negatively and significantly associated with fewer armed attacks in other grades, but not in high schools, while the frequency of possession of weapons was lower in other schools, but significantly higher in high schools. In addition, schools with predominantly minority populations often face higher levels of reported violence and have a stronger police presence [

19]. All this may indicate that the presence of the police is counterproductive, but it may also be a reflection of the police work while trying to solve the already existing problem of crime in schools.

There is a small number of studies in Serbia with the work of a school police officer as the subject of research. The first research on this topic was [

36], which covered the initial steps of the implementation of the School Police officer program, without going into a deeper consideration of the effectiveness of the mentioned program. The research of Milojević et al. [

8] has already been mentioned, which indicated that since the introduction of the school police officer, there has been a significant increase in the number of criminal acts in Serbian schools. In the research conducted by Spasić and Kekić [

28], in which the attitudes of students and employees about school police officers were examined, the respondents indicated that in all schools where school police officers are not represented, their engagement is necessary, that is, measures and activities are recommended on improving their engagement in those schools where they have already been assigned. Other papers mention the school police officer as one of the programs implemented to increase the safety of students in schools [

1,

4,

37,

38].

2. Materials and Methods

The ex–post analysis was conducted through PEST/SWAT analysis, mapping of the key actors and using batteries of online questionnaires. There were seven questionnaires: a questionnaire for elementary and high school students, a questionnaire for parents, a questionnaire for teaching staff, a questionnaire for principals and secretaries, a questionnaire for professional associates, a questionnaire for the Team for protection against discrimination, violence, abuse and neglect, and a questionnaire for police officers. Besides interviews with the MOI representatives, the following was conducted: Survey with personal interviewing, Computer–aided surveying and Desk analysis and content analysis. The research was conducted in the period from September 2021 to June 2022. The research methods were implemented in 1140 schools in Serbia. 8,617 people were included in all of them. The questionnaire for police officers included 308 police officers, the questionnaire for principals and secretaries included 1085 participants, the team for protection of discrimination questionnaire included 982 participants, teachers and staff questionnaire included 2988 participants, parents’ questionnaire had 938 participants and student’s questionnaire included 2316 participants. The goal of the research and ex–post analysis was to compare activities and results of implementing powers of police officers in schools with results in the field. It was to be done comparing the focused groups’ responses and results of the implementation.

2.1. Study Area

During 2002, fundamental reforms of the police began in Serbia, which, among other things, related to the reaffirmation of police officers, sectoral work and the introduction of school police officers [

38]. The “School Police officer” project began in 2002. It was initiated by a joint assessment by the Ministry of Education and Sports and the Ministry of Interior that the security situation in a number of schools in urban areas of Serbia is significantly threatened [

28].

Unlike SROs in the USA, which has a triple role determined through the “triad model”, the role of the school police officer in Serbia is law enforcement exclusively [

8]. The tasks of the school police officer are defined in such a way that they emphasize the preventive role of members of the police who perform the duties of the school police officer [

36]. The school police officer intervenes only when it is necessary and in order to protect students and the school property. One of the reasons is that the crime rate in schools is not high, and the forms of criminal acts were not as extreme as in other countries [

1], so for example in Serbia there had not been a problem of mass school shootings, such in the USA [

19,

39].

When the “School Police Officer” program was launched, 185 police officers were engaged in it [

36]. Since the beginning of the implementation of the project, the number of “school police officers" has been increasing, so that until the mass shooting at the school in Belgrade, 381 school police officers were employed in 664 schools (348 elementary and 327 high schools) in Serbia [

4]. School police officers were not deployed in all schools, some of them covered several schools, and in some cases they only occasionally visited schools [

40], which was also the case with the school in Belgrade, where a mass shooting took place. Just a few days after the shooting in the elementary school in Belgrade, the Ministry of Interior of Serbia, as one of the measures to increase security in schools, ensured the constant presence of a school police officer in all secondary and elementary schools in Serbia. Currently 3,448 police officers are deployed in 1844 schools to ensure their security, while 1,200 new police officers are expected to be recruited for these jobs [

41].

The criteria for a school police officer exist, but without a clear definition. They are of a general type: the ability to work effectively with students, with parents and with principals, knowledge of legal issues related to the functioning of schools, knowledge of existing school resources, knowledge of social service resources, understanding of developmental child psychology, knowledge of crime prevention, public speaking skills, knowledge of school security technology, etc. [

28]. There are no tests to determine whether someone has certain knowledge and skills, but everything is based on the free assessment of the senior police officers, who evaluate whether the police officers possess them or not. Another problem is that after the selection, no implementation of further specific training is envisaged [

8,

28].

2.2. Socio–economic and demographic characteristics

Out of the total number of school police officers, 70.6% of respondents are male and 29.1% of respondents are female. The majority of respondents (35.3%) are between 46 and 55 years of age, while the fewest number of respondents are under 25 (7.1%). Observed about education, the majority of respondents have completed high school (80.6%). According to years of work experience in the service, the largest number of respondents (30.4%) has up to 20 years of work experience, while the smallest number of respondents (3.9%) has up to 2 years of work experience. Regarding years of work as a school police officer, the largest number of respondents (21%) have up to 20 years of work experience, while the smallest number of respondents (4.5%) have up to 10 years of work experience. In the largest number of schools, (39.5%) there have been school police officers for over 16 years, while in the smallest number of schools (7.52%) there have been school police officers for only five years.

About students who participated in the research, most of the respondents (96%) have completed elementary school, while the fewest number (3.9%) have completed high school. When it comes to the perception of feeling safe at school, the largest number of respondents (75.6%) point out that they feel safe, while the smallest number of respondents (0.4%) point out that they feel unsafe to some extent. In relation to the number of students in a school, there are from 200 to 500 students in the largest number of schools (30.5%), while there are over 1000 students in the smallest number of schools (7.9%). In the largest number of schools (38.7%) there are school police officers, while in 38.7% they have not been deployed (

Table 1).

2.3. Questionnaire Design

In preparing the questionnaire for this study, several approaches were considered [

8,

21,

27,

29,

30,

42] and seven questionnaires were carefully prepared for online usage and controlling the participation of focused groups of participants. The research was conducted as non–experimental, explorative and descriptive research, with general research goal set in the previous explanation. Research activities that were conducted included are as follows: Survey with personal interviewing, Computer–aided surveying and Desk analysis and content analysis. Survey research was developed and conducted through structured survey and interview, by specially trained persons.

After conducting an online survey using the Survey Monkey software solution, the data obtained using measuring instruments were processed using statistical methods. Hired consultants carried out the primary processing of the completed questionnaires, and the results are presented in this document. The analysis of the content and results of the cross–examination was carried out with consideration of all the proposed directions of analysis. During the preparation of the research, data sources and deadlines for the realization of the research were defined, as well as the procedure for processing the data and unifying the results. Although several focus groups were planned to deepen the research results, due to the restrictions caused by the Covid–19 pandemic [

43], the focus groups were not held. The Helsinki Declaration [

44], which set standards for socio–medical research involving human participants, was in accordance with our quantitative analyses. An initial invitation to participate in an online survey was made on social media, and the participants were selected using a convenience sample strategy. Serbia was included in the research.

2.4. Analyses

Descriptive data were acquired for the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of the participants in this study. The relationships between the covariates and perception of the school police officer were investigated using the t–test, one–way ANOVA, multivariate linear regression, and binary regression. The findings of two tests resistant to the violation of the assumption, Welch’s t–test and the Brown–Forsythe test were utilized since the preliminary examination of the homogeneity of variance (test of homogeneity of variances) revealed a violation of the assumption of homogeneous variance. All tests had a significance threshold of p 0.05 and were two–tailed. SPSS Statistics was used to conduct the statistical analysis (IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 26, New York, NY, USA). With a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84, the Likert scale’s internal consistency was good.

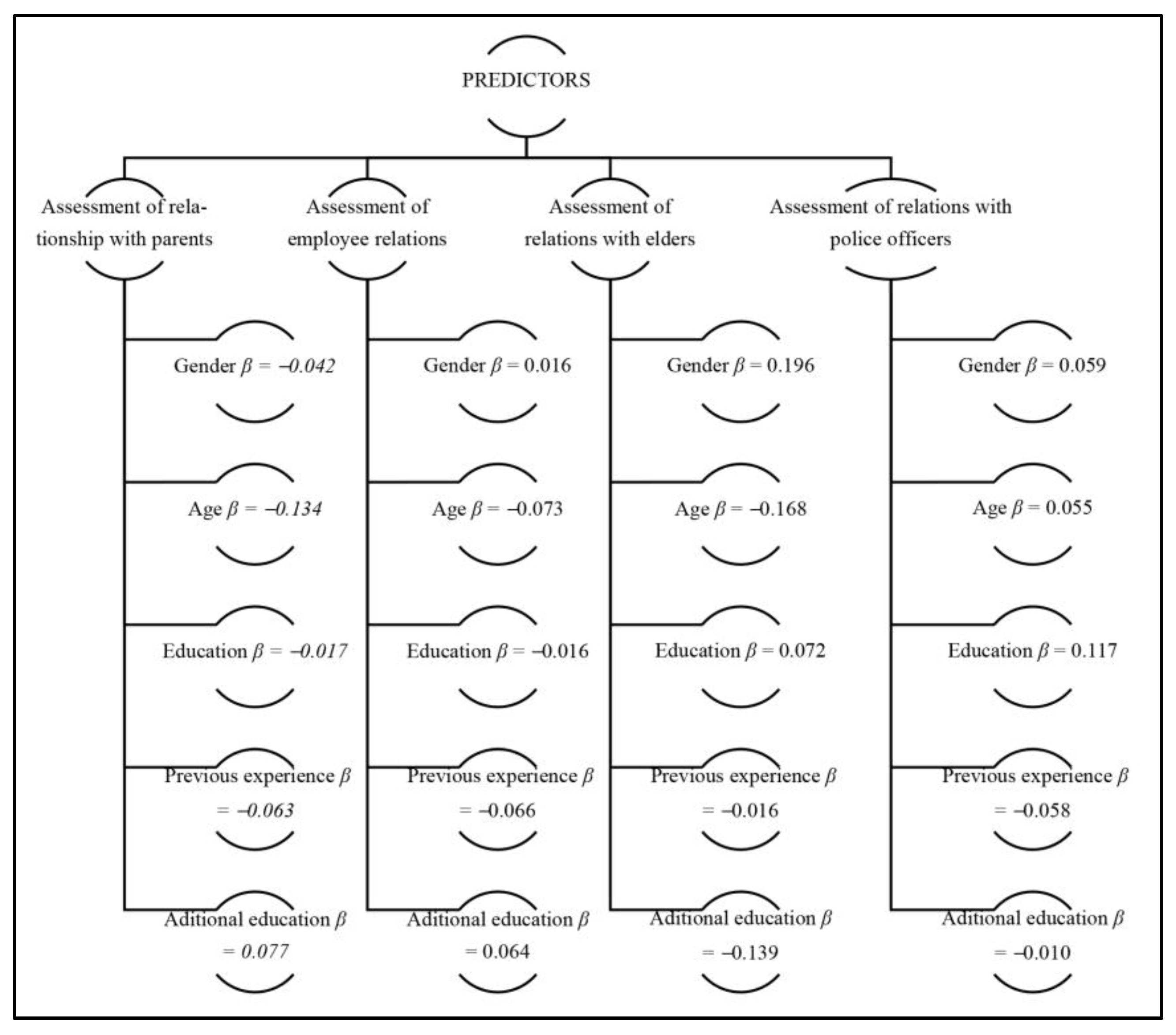

We performed regression analyses with the five independent variables (gender, age, education, previous experience and additional education) to examine the factors associated with the overall scale (

Table 2). Four dependent variables (security procedures, time of realization, improvement of cooperation, safety improvement) were included in the multivariate logistic regression model (

Table 3). A multivariate regression analysis was used, identifying the extent to which total scores of the primary dependent variables (e.g., assessment of relationship with parents, assessment of employee relations, assessment of relations with senior police officers, assessment of relations with police officer’s subscale) were associated with five demographic and socioeconomic variables: gender, age, education, previous experience and additional education. Previous analyses reviewing the residual scattering diagram showed that the assumptions of normality (normal probability plot P–P and scatterplot), linearity, multicollinearity (

r = 0.9), and homogeneity of variance had not been violated.

3. Results

Based on the methodological framework and study design above, the results were divided into three groups:

1. Predictors of the attitudes of school police officers;

2. Results of descriptive statistics regarding attitudes of school police officers (Perception of school police officers, Teachers’ perception of school police officers, Student’s perception of school police officers);

3. Correlations between the variables and the attitudes of school police officers.

3.1. Predictors of the school attitudes of school police officers

The multivariate regression analyses showed that gender, education, previous experience and additional education did not significantly affect assessment of relationship with parents. On the other hand, the major predictor of assessment of relationship with parents is age (

β = −0.134), explaining 12.9% variance in the score. The assessment of relationship with parents’ model (

R2 = 0.35, Adj.

R2 = 0.18,

F = 2.11,

t = 37.3,

p = 0.05) with all the mentioned independent variables explains the 18% variance of relationship with parents (

Table 2 and

Figure 1).

The assessment of relationship with employees’ model (

R2 = 0.18, Adj.

R2 = 0.02,

F = 1.10,

t = 44.4,

p = 0.36) with all the mentioned independent variables did not show a statistically significant value. The assessment of relationship with supervisor model (

R2 = 0.86, Adj.

R2 = 0.70,

F = 5.50,

t = 39.8,

p = 0.00) with all the mentioned independent variables explains the 7% variance of assessment of relationship with supervisor. The most important predictor of the assessment of relationship with supervisor model is gender (

β = 0.196), which explains 1.88% variance in the score, followed by age (

β = −0.168, 1.62%), and additional education (β = −0.139, 1.34%). The remaining variables did not have significant effects on assessment of relationship with supervisor. On the other side, the assessment of relationship with police officers (

R2 = 0.03, Adj.

R2 = 0.01,

F = 1.76,

t = 41,

p = 0.12) with all the mentioned independent variables did not show a statistically significant value (

Table 2 and

Figure 1).

In the first step, logistic regression was used to determine the combined effects of the various factors included in the proposed model (gender, age, education, additional education) (

Table 3). The logistic regression model applied to the security procedures (with all predictors) was not statistically significant (χ2 = 8.66; (5, N = 302)

p ≤ 0.07).

The model including the time of realization (with all predictors) was statistically significant (χ2 = 9.7; (4, N = 260)

p ≤ 0.01) and explains the variance between 3.1% (Cox & Snell) and 5.3% (Nagelkerke). Regression results indicated that the one predictor had a statistically significant contribution to the model (educational level;

p ≤ 0.01). The educational level was found to be the strongest predictor of the time of realization with a regression coefficient of 2.74. This indicates that twice as many respondents who are more educated assess that they have enough time for the realization of all activities compared to those who are not. The model including the improvement of cooperation (with all predictors) was not statistically significant (χ2 = 7.14; (4, N = 299)

p = 0.12). On the other hand, the model including safety improvement (with all predictors) was statistically significant (χ2 = 23.68; (4, N = 309) p ≤ 0.00) and explains the variance between 7.4% (Cox & Snell) and 12.4% (Nagelkerke). Regression results indicated that the three predictors had a statistically significant contribution to the model (age –

p = 0.002; educational level –

p = 0.003; and additional education –

p = 0.002;). The educational level was found to be the strongest predictor of the safety improvement with a regression coefficient of 2.15. This indicates that more educated respondents assess that they will contribute to safety improvements more than to those who are not (

Table 3).

3.2. The results of descriptive statistics regarding attitudes, trust and presence of school police officers

Out of the total number of police officers performing the duties of a school police officer, 47.2% have completed specialized training for performing the duties of a school police officer. The largest number of respondents (42.7%) have completed a seminar for a school police officer. The jobs of the school police officer are performed in the largest number of cases (44.7%) in mixed schools, followed by one elementary school (23%), and the least in one high school (9.4%). Schools informed 89.6% of police officers about their own procedures and ways of doing things to ensure the safety of students and schools. The results show that 79% of respondents point out that there are clearly planned goals and tasks of the school police officer, 84.1% believe that there is enough time to complete all defined tasks (

Table 4).

In relation to notifications by the school about security incidents, 73.8% point out that the school submits a report to the police when necessary, 16.8% point out that they notify only the specific police officer who performs the duties of a school police officer, while 6.8% believe that they do not inform him about security incidents. Involvement of school police officers in other activities that are not part of the work tasks at the request of the principal, employees, parents and children was also studied. 45.6% point out that 8.7% of the school police officers did not accept other activities because they were not specified in the description of the tasks that were performed. It was further investigated whether engagement contributes to the improvement of safety in the school and the results show that 83.2% of respondents believe that they contribute to this and the majority of respondents 82.2% have no suggestions for improving the “school police officer” project (

Table 4).

Regarding students’ perception of school police officers

, results show that the majority of respondents (65%) point out unpleasant things do not happen, while only 12.3% point out that unpleasant things happen mostly outside of school. When it comes to turning to the school police officer for help in such situations, 12.4% always turn to the school police officer in such situations and he always helps them. On the other hand, 14% do not contact the school police officer in such situations, while 39.5% point out that they do not have a school police officer. In relation to the visibility of the school police officer in the school premises, 16.5% point out that they often meet him on the way to school, while 13.6% claim that they sometimes meet him. In addition, 16% know the school police officer and always contact him, while 10.1% point out that they never contact the school police officer because they do not know if he knows them and 1.3% are too shy to contact the school police officer. In further results, it was determined that 33.9% of the respondents feel safe because the school police officer is nearby and because they can turn to him for help. In addition, it was found that 35.6% of respondents believe that they feel safer because the school has a school police officer (

Table 5).

Regarding teachers’ perception (trust and presence) of school police officers, it was determined that 31.4% of teachers know the working hours of the school police officer during school hours. In contrast, 42.2% of respondents do not know such working hours. About 40.1% of respondents are partially informed about the school police officer, 25.9% believe that there is not enough information about the project and 1.7% are informed via the school’s website. Examining attitudes about the need for school police officers, it was determined that the majority of teachers (58.9%) believe that there is a need and that everyone feels safer when he is present in the school premises. In addition, 11.1% believe that it is not necessary because the school is located in a safe area where incidents rarely occur, and 8.2% believe that they do not know if there is a need for it. In relation to the assessment of the school police officer’s familiarity with the security issues of the school he is in charge of, about 50.2% believe that the school police officers are aware of the school’s security issues, while 22.1% are not sure. Certainly, the results show that the majority of teachers, 53%, trust and believe they have support from the school police officer and that they expect him to be always there and ready to help, while 7.9% believe that such support is needed in accordance with established procedures and at the request of the school principal. 4.2% of respondents believe that the school police officer cares about the safety of citizens.

When it comes to the qualities of a school police officer, 26.4% believe that he should be familiar with the premises as well as with students and school employees, he should be communicative and tolerant (20.2%) have self–initiative (9.6%) and be open to new knowledge (11%). We further examined different attitudes and found the following: 45.6% believe that the school police officer is an important participant in the process of creating a safe and secure environment and that his presence contributes to increasing the safety around the school, while 2.6% believe that his role is not important. The largest number of respondents (41.3%) are not sure whether the negative impacts of facilities around the school have been reduced after the introduction of the school police officer. Only 18.5% believe that the negative impact has been reduced because of such introduction. About 30% believe that prevention measures have been increased in the school and its surroundings after the introduction of the school police officer; 17.9% believe that the introduction of a school police officer is an effective method of safety prevention and, if necessary, intervention around the school. Further results show that 26.1% of respondents believe that seminars, conferences and other activities related to school safety are regularly held, while 2.8% believe that they do not believe that there were any. At school, 62.4% of teachers feel safe, while 0.3% do not feel safe at all. 24.7% of respondents feel mostly safe, while 0.1% feel fear and discomfort. Within the school environment, 53.2% feel comfortable and safe while only 0.5% do not feel safe at all on the way to school. In relation to the feeling of safety in the school now or before the introduction of the school police officer, the results show that 46% believe that they feel safer now, while 36.7% claim that there is no difference. The evaluation of the relationship between the school police officer and teachers shows that the majority of respondents (49.3%) think that such a relationship is excellent, while 1% think that such a relationship is very bad. On the contrary, the assessment of the relationship between the school police officer and students shows that the majority of respondents (49%) think that such a relationship is excellent, while 0.8% believe it is very bad.

With respect to the assessment of the importance of the role of the police in various types of violence, it was determined that the assessment of importance is the highest (67.6%) in terms of intimidation, blackmail with serious threats, extortion of money or things, preventing movement, offering drugs and alcohol. On the other hand, it is the lowest in sexual touching, showing pornographic material, showing intimate parts of the body and undressing (34.9%). Examining the level of assistance from school police officers shows that 59.4% of respondents were not in a situation to seek the assistance of the school police officer, while 5.1% stated that it happened three to five times. Assessment of the need for school police officers show that 65% of respondents believe that their introduction is necessary, while 5.7% point out that it is not necessary. In this regard, 51% of teachers believe that the introduction of a school police officer is a good idea and that it can bring numerous benefits (

Table 6).

3.3. Correlations between the variables and the attitudes of school police officers

T–test results show that there is a statistically significant correlation between men and women regarding the assessment of the realtionship with senior officers (

p = 0.000) and the assessment of the relationship with other police officers (

p = 0.09). Further analyses show that men (M = 4.63) have a higher score when they assess the relationship of police officers and senior officers than women (M = 4.30). Moreover, it was determined that men (M = 4.58) have a higher score when assessing the relationship of police officers with senior officers in police stations than women (

Table 7).

In further analyzes of the Chi square test, it was determined that there is a statistically significant correlation between gender and the following variables: planned goals and tasks (

p = 0.00) and other non–task activities (

p = 0.00). When it comes to the age of the respondents, its statistically significant correlation with the following variables was determined: security procedures (

p = 0.00); planned goals and objectives (

p = 0.00); time of activity realization (

p = 0.00); informing about situations (

p = 0.00); other activities outside tasks (

p = 0.00); suggestions for improving cooperation (

p = 0.00); safety improvement (

p = 0.00) (

Table 8).

In relation to previous experience, a statistically significant correlation was established with the following variables: security procedures (

p = 0.00); planned goals and objectives (

p = 0.00); time of activity realization (

p = 0.00); informing about situations (p = 0.00); other activities outside tasks (

p = 0.00); suggestions for improving cooperation (

p = 0.00); safety improvement (

p = 0.00). When it comes to the additional education of school police officers, a statistically significant correlation was established with the following variables: security procedures (

p = 0.00); planned goals and objectives (

p = 0.00); time of activity realization (

p = 0.00); informing about situations (

p = 0.00); other activities outside tasks (

p = 0.00); suggestions for improving cooperation (

p = 0.00); safety improvement (

p = 0.00) (

Table 8).

Further analyses in relation to gender show that men emphasize that there are clearly planned goals and tasks of the school police officer more than women (men – 84.9%; women – 65.6%); to get involved in other activities that are not part of work tasks at the request of principals, employees or parents and children (men – 50.5%; women – 24.4%).

On the other hand, further analysis regarding age shows that respondents aged 45–55 mostly (95.4%) point out that the school introduced them to all the procedures and ways of doing things to ensure the safety of students and schools, while on the other hand, this is claimed to the smallest extent (59.1%) by respondents younger than 25 years old. Very similar results were also obtained when it comes to whether there are clearly planned goals and tasks of the school police officer, and it was determined that respondents aged 45–55 point out that there are mentioned goals and tasks to the greatest extent (90.8%), unlike the respondents under 25 years of age (50%). Respondents aged 45–55 point out that they have enough time to complete all defined tasks to the greatest extent (92.7%) compared to respondents aged 26–35 (71.8%). In addition, respondents aged 45–55 point out that the school informs them about security incidents that occur in the absence of school police officers to the greatest extent (82.6%) compared to respondents under 25 years of age (54.5%). Also, respondents aged 45–55 point out that they get involved in activities that are not part of work tasks at the request of principals, employees or parents and children to the greatest extent (58.7%) compared to respondents under 25 years of age (9.1%). It is interesting to point out that young people over 25 years of age (95.5%) do not have suggestions for improving cooperation with school police officers. Further analysis shows that respondents aged 45–55 believe that engagement of school police officers contributes to the improvement of school safety to the greatest extent (92.7%) compared to respondents under 25 years of age (50%).

In relation to previous experience in the performance of police work, the results show that the respondents who have up to 30 years of work experience point out that the school introduced them to the procedures and ways of acting to achieve the security protection of students and schools to the greatest extent (97.6%), while respondents with up to 2 years of work experience make up the least amount (23.1%). Respondents who have up to 30 years of work experience point out that there are clearly planned goals and tasks of the school police officer to the greatest extent (91.7%) compared to respondents who have up to 2 years of work experience (15.4%). In addition, respondents with up to 30 years of work experience point out that they have enough time to complete all defined tasks the most (92.8%), while respondents with up to 2 years of work experience do so the least (61.5%). Respondents with up to 30 years of work experience point out that the school informs them about security incidents and that they submit a report to the competent police station to the greatest extent (83.1%) compared to respondents (45%) with up to 2 years of work experience. In addition, it was determined that respondents who have up to 30 years of work experience to the greatest extent (92.8%) believe that engagement of police officers can contribute to improving school safety.

Bearing in mind the additional education for performing the duties of a school police officer, the results show that the respondents who have undergone additional education (97.2%) largerly point out that the school introduced them to its procedures regarding actions in achieving the security protection of students and schools compared to those who have not undergone additional education (85.5%). Moreover, respondents who have undergone additional education point out there are clearly planned goals and tasks of the school police officer more (82.8%) than those who have not (78%). In addition, it was determined that such respondents emphasize that they have enough time to complete the defined tasks more (87.6%) than those without additional education (83.6%). They are more inclined to emphasize that the school informs them about security incidents that occur in their absence (78.6%) compared to those without additional education (71.7%). They also point out that they get involved in other activities that are not part of their work tasks at the request of principals, employees or parents and children more (49.7%) compared to those without additional education (37.7%). When it comes to improving cooperation with other police officers and senior officers, the results show that respondents who have undergone additional education believe that they have no suggestions for such improvement more (84.1%) than those without additional education (83.6%). They emphasize that their engagement contributed to the improvement of safety at school more (93.1%) than those who did not undergo such additional education (76.7%).

ANOVA results show that there is a statistically significant correlation between age and the following variables: assessment of the relationship with school principals (

p = 0.00); assessment of relationship with parents (

p = 0.00); assessment of relations with employees (

p = 0.01); assessment of relationship with senior police officers (

p = 0.00); assessment of relationships with colleagues (

p = 0.00). In relation to the previous experience, a statistically significant correlation was established with the following variables: assessment of the relationship with school principals (

p = 0.06); assessment of relationship with parents (

p = 0.07). In relation to additional education, it was determined that there is a statistically significant correlation with one variable related to the assessment of the relationship with parents (

p = 0.06) (

Table 9).

Further analysis shows that respondents aged 46–55 had the highest score (x = 3.24; sd = 0.94) while assessing the relationship between school police officers and school principals; then with the employees of the school where they are employed (x = 4.70; sd = 0.53), as well as with senior police officers (x = 4.68; sd = 0.59). The highest score (x = 4.50; sd = 0.73) of the assessment of the relationship with children and parents of the schools in which they are engaged was recorded in respondents aged 36–45. In relation to previous experience, it was determined that respondents with over 30 years of work experience assessed the relationship with school principals with the highest score (x = 4.92; sd = 0.28). In addition, it was determined that respondents with more than 20 years of work experience assess the relationship with the children and parents of the schools in which they are employed with the highest score. When it comes to additional education, the results show that respondents who have additional education assess the relationship with children and parents in the schools where they are engaged with the highest score (x = 4.46; sd = 0.71) (

Table 9).

4. Discussion

It was shown in our study that, as in similar earlier research conducted in the USA [

27], and in Serbia [

8,

28], students feel safer when the school has a school police officer. However, very few students turn to school police officers for help or contact them at all, indicating that there is little interaction between them. Theriot and Cuellar [

45] indicated in their research that students who have a greater number of interactions with police officers at school have a more positive attitude towards them, and in our research, the data indicate that such interaction in Serbia is at a low level.

On the other hand, school police officers rate their relationship with principals and teachers as excellent, and the weakest relationship is with children and parents. Such data also indicate that school police officers have a weak interaction with students. As already pointed out by Fix et al. [

26], one of the shortcomings of training in the USA is that police officers receive minimal training on how to understand adolescents and how to communicate with them, and this is clearly the problem of Serbian police officers as well, as we have already stated that they do not have adequate specialized training.

Teachers in Serbia, in large numbers, believe that school police officers are necessary for schools, they receive support from school police officers, and they have a positive attitude towards school police officers on all issues. The results obtained on this issue do not differ in many ways from the attitudes of school employees in previously conducted studies, both in Serbia and in other countries [

4,

13,

27,

28,

30]. The school police officers themselves agree largely with the views of the teachers, that a school police officer is necessary for the school because they believe that the deployment of a school police officer improves safety in the school.

From the presented research results, it could be seen that more than half of the school police officers have not completed any specialized training. In comparison to the research in Texas, that number is 40% [

25]. However, the problem in Serbia is even greater because only 5.8% of respondents stated that they completed a certain course, and 42.7% of them completed a seminar, which lasted one or two days. The question is whether it is possible to provide someone with at least basic knowledge and not provide the broader training that is necessary for a school police officer. The answer is no. From the above, it can be concluded that only 5.8% of school police officers have certain specialized training for the job, which is the unacceptable data. Therefore, we would agree with the statement from the previous research by Milojević et al. [

8] that there is no organized specialized training in Serbia for a school police officer, which is otherwise a prerequisite for the successful work of a school police officer [

23].

Another worrying fact is that only about 1/3 of school police officers in Serbia perform their activities in one school, while the rest work in two or more schools. The fact this is not a good practice was confirmed in the massacre at the elementary school in Belgrade, where a police officer occasionally visited the school, but was not at the school at the time of the shooting. We are not sure if she could have completely prevented the crime, but we assume that the consequences would have been less devastating. This is the extreme form of violence; however, with a partial presence in the school, the school police officer is not able to fully accomplish other, often simpler, tasks.

When it comes to the limitations of the conducted research, it should be noted that the research was conducted before the mass shooting in the elementary school in Belgrade. We assume that the results of the research would be somewhat different now, but not more dramatic, because even then, the respondents had a positive attitude about the school police officer, and now this would probably be the same. In any case, a subsequent investigation should be conducted, after the mentioned event, in order to have a complete insight into the current situation. Moreover, it can be seen that a number of answers are missing in tables showing the results, which is perhaps more notable than in other surveys, but since there was a large number of respondents, we consider the data to be valid.

This is the first study in Serbia and Southeast Europe that examined the role and importance of the school police officer, with a large number of respondents from different categories. The research has a special significance for the current situation in Serbia, because school police officers were introduced en masse in all schools after the mass shooting in the elementary school in Belgrade. This study can contribute to the positive direction of this trend, so that the “school police officer” program can be successfully implemented in schools throughout Serbia. Besides, it can help to overcome the current difficult situation and reduce fear among children in schools.

5. Conclusions

Although the data for our research was collected before the unfortunate events in Belgrade, the results suggest that the entire public (students, parents, teachers, principals, school police officers) believe that a school police officer is needed in schools and that he has a very positive effect on school safety. After the mass shooting at the school in Belgrade, we believe that the public will be even more convinced that it is necessary. However, the simple presence of the school police officer in the premises is not enough; his work must be improved. That is why it is necessary to undertake three types of measures: regulatory, informative-educational and institutional-organizational.

Within the first group of measures, it is necessary to establish a school police officer institute within formal frameworks, that is, to systematize the job position – the school police officer, because currently the said job is performed by different police officers, who are not sufficiently trained in the field. It is necessary to draw up instructions for this job, which will regulate the actions of a school police officer in detail.

Institutional–organizational measures include the definition of clear criteria that a police officer can perform the duties of a “school police officer”, because they do not exist now. In addition, the question arises whether every school needs a school police officer. That is why it is necessary to define clear, minimum criteria for the introduction of a “school police officer” in a certain school (number of students, distance from the police station, coverage by patrol and police activities, number of committed offenses and criminal acts in and around the school, number of disciplinary measures imposed in by the school, etc.), by which his introduction to the school according to someone’s “free judgment” would be avoided. In order to improve the work of the “school police officer” and exchange experience, it is necessary to connect all school police officers in the “School Police Officer Network”, through internal police networks or through social networks, in order to exchange experiences on security–related issues in schools. One of the most important rules would be “one school police officer – one school”, which was not applied at the time of the school massacre in Belgrade. In many schools in Serbia, one school police officer works in two or more schools, often during a short period. The school police officer is not able to fulfill his tasks completely due to his partial presence in the school, which was also the case in the case of the massacre in the elementary school in Belgrade, because she was not present at the time of the attack.

Informational and educational measures include the establishment of special training for school police officers and the creation of a training program (Handbook) for the “school police officer”. In accordance with the newly created situation in Serbia, one part of the training would have to refer to the actions of school police officers in AMOK situations, that is, mass shootings in schools. In addition to independent trainings for school police officers, it is necessary to conduct joint trainings with school representatives. All the above measures would help each school where security is threatened, to get its own school police officer, who will contribute to increasing the safety of students in schools, feeling of safety of students and employees, and particularly help to avoid tragedies like the one that happened in the elementary school in Belgrade.

Author Contributions

B.J. and V.M.C. had the original idea for this study and developed the study design and questionnaire in collaboration with Z.I., S.P. and B.O. contributed to the dissemination of the questionnaire; V.M.C. analyzed and interpreted the data with B.J. and Z.I., S.P., B.O. and Z.I.. made special contributions by drafting the introduction; S.P. and Z.I. drafted the discussion and B.O. drafted the conclusion; V.M.C and Z.I., S.P., and B.O. critically reviewed the data analysis and contributed to the content when revising and finalizing the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Scientific-Professional Society for Disaster Risk Management and International Institute for Disaster Research (protocol code 001/2022, 7 October 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Stevanović, I.; Zečević, O. Krivična dela maloletnika u vezi sa drogom-prevencija i suzbijanje [Drug-Related Juvenile Delinquncy - Prevention and Suppresion]. In Droga i narkomanija: pravni, kriminološki, sociološki i medicinski problemi; Milićević, M., Stevanović, I., Eds.; Institut za kriminološka i sociološka istraživanja: Beograd, 2020; pp. 287–299. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, B. Understanding and assessing school police officers: A conceptual and methodological comment. Journal of Criminal Justice 2006, 34, 591–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, G.C.S. School-Community Collaboration: Disaster Preparedness Towards Building Resilient Communities. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2019, 1, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekić, D.; Spasić, D. Učešće policije u video-nadzoru u školama na području policijske uprave za grad Beograd − tradicija, stanje i perspektive razvoja [Participation of Police in Video-Control in Schools in the Area of Police Department for City OF Belgrade - Tradition, the State and Prospects of Development]. In Bezbednost u obrazovno-vaspitnim ustanovama i video-nadzor; Lipovac, M., Stanarević, S., Kešetović, Ž., Eds.; Univerzitet u Beogradu, Fakultet bezbednosti: Beograd, 2018; pp. 98–110. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, J.M.R.; Jetelina, K.K.; Jennings, W.G. Structural school safety measures, SROs, and school-related delinquent behavior and perceptions of safety: A state-ofthe-art review. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 2016, 39, 438–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, B.W.; McKenna, J.; Higgins, E.M.; Maguire, E.R.; Homer, E.M. The Alignment Between Community Policing and the Work of School Resource Officers. Police Quarterly 2022, 25, 561–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes, A.N.; Mears, D.P.; Collier, N.L.; Pesta, G.B.; Siennick, S.E.; Brown, S.J. Blurred and Confused: The Paradox of Police in Schools. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 2021, 15, 1546–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milojević, S.; Janković, B.; Milojković, B.; Djukanović, S. Effectivness of the School Police Officer Program. In Archibald Reiss days, Simeunović-Patić, B., Ed.; The Academy of Criminalistic and Police Studies, Belgrade: Belgrade, 2017; pp. 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- MUP, S. U Osnovnoj školi „Vladislav Ribnikar" na Vračaru ubijeno osmoro dece i radnik obezbeđenja [Eight children and a security guard were killed in the "Vladislav Ribnikar" Elementary School in Vračar]. Available online: http://www.mup.gov.rs/wps/portal/sr/aktuelno/saopstenja/086bb2b0-0751-4b31-b08b-0f95042fb1bb (accessed on 14.05.).

- Scheuermann, B.; Billingsley, G.; Dede-Bamfo, O.; Martinez-Prather, K.; White, S.R. School Law Enforcement Officer Perceptions of Developmentally Oriented Training. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 2021, 15, 2283–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broll, R.; Howells, S. Community Policing in Schools: Relationship-Building and the Responsibilities of School Resource Officers. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 2021, 15, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henshall, A. On the school beat: police officers based in English schools. British Journal of Sociology of Education 2017, 39, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öğülmüş, S.; Pişkin, M.; Kumandaş, H. Does the school police project work? The effectiveness of the school police project in Ankara, Turkey. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 2011, 15, 2481–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Connell, N.M. The Effects of School Police Officers on Victimization, Delinquency, and Fear of Crime: Focusing on Korean Youth. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 2021, 65, 1356–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenta, Z.; Butković, A.; Karlović, R. Osvrt na dosadašnji rad kontakt-policajaca Policijske uprave zagrebačke. Policija i sigurnost 2019, 28, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, J.B.; Katsiyannis, A.; Counts, J.M.; Shelnut, J.C. The Growing Concerns Regarding School Resource Officers. Intervention in School and Clinic 2017, 53, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, C.; Gottfredson, D.; Hutzell, K. Can school policing be trauma-informed? Lessons from Seattle. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 2016, 39, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivey, C.A.S. Teaching, counseling, and law enforcement functions in South Carolina high schools: A study on the perception of time spent among school resource officers. International Journal of Criminal Justice Sciences 2012, 7, 550–561. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, C.; Burns, R. Reducing school violence: Considering school characteristics and the impacts of law enforcement, school security, and environmental factors. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 2016, 39, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, C.G.; Gainey, R.R.; Chappell, A.T. The effects of social and educational disadvantage on the roles and functions of school resource officers. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 2016, 39, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, T. School Resource Officer Perceptions and Correlates of Work Roles. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 2019, 13, 498–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, P.C.; Kremser, J.; Walker, H. Detention or diversion? The influence of training and education on school police officer discretion. Policing: An International Journal 2019, 42, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Counts, J.; Randall, K.N.; Ryan, J.B.; Katsiyannis, A. School Resource Officers in Public Schools: A National Review. Education and Treatment of Children 2018, 41, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotman, D.; Thomas, L. Police Community Support Officers in Schools: Findings from an Evaluation of a Pilot Training Programme for School Liaison Officers. Policing 2016, 10, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Prather, K.E.; McKenna, J.M.; Bowman, S.W. The impact of training on discipline outcomes in school-based policing. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 2016, 39, 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fix, R.L.; Aaron, J.; Greenberg, S. Experience Is Not Enough: Self-Identified Training Needs of Police Working with Adolescents. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 2021, 15, 2252–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrusciel, M.M.; Wolfe, S.; Hansen, J.A.; Rojek, J.J.; Kaminski, R. Law enforcement executive and principal perspectives on school safety measures. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 2015, 38, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spasić, D.; Kekić, D. Bezbednost u školama i angažovanje školskih policajaca [School safety and engaging school police officers]. In Reagovanje na bezbednosne rizike u obrazovno-vaspitnim ustanovama; Kordić, B., Kovačević, A., Banović, B., Eds.; Univerzitet u Beogradu, Fakultet bezbednosti: Beograd, 2012; pp. 181–195. [Google Scholar]

- Theriot, M.T. The impact of school resource officer interaction on students’ feelings about school and school police. Crime & Delinquency 2016, 62, 446–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, S.E.; Chrusciel, M.M.; Rojek, J.; Hansen, J.A.; Kaminski, R.J. Procedural Justice, Legitimacy, and School Principals’ Evaluations of School Resource Officers: Support, Perceived Effectiveness, Trust, and Satisfaction. Criminal justice policy review 2017, 28, 107–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, Q.W. School resource officers and school incidents: A quantitative study.. The University of Alabama, 2011.

- Na, C.; Gottfredson, D.C. Police Officers in Schools: Effects on School Crime and the Processing of Offending Behaviors. Justice Quarterly 2013, 30, 619–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfredson, D.C.; Crosse, S.; Tang, Z.; Bauer, E.L.; Harmon, M.A.; Hagen, C.A.; Greene, A.D. Effects of school resource officers on school crime and responses to school crime. Criminology & Public Policy 2020, 19, 905–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, W.G.; Khey, D.N.; Maskaly, J.; Donner, C.M. Evaluating the relationship between law enforcement and school security measures and violent crime in schools. Journal of police crisis negotiations 2011, 11, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, C.; Burns, R. Preventing school violence: assessing armed guardians, school policy, and context. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 2015, 38, 631–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bošković, G.; Simić, B. Iskustva u realizaciji projekata “Školski policajac – prijatelj i zaštitnik dece” [Experiences in the implementation of projects "School policeman - friend and protector of children"]. Bezbednost 2004, 46, 761–774. [Google Scholar]

- Ninčić, Ž. Vršnjačko nasilje kao oblik socijalne destrukcije [Peer Violence as a Form of Social Destruction]. Kultura polisa 2022, 19, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristović, S. Tradicionalni i savremeni model rada policije na bezbednosnom sektoru [The Traditional and the Modern Model of Police Work in the Security Sector]. Civitas 2021, 11, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsiyannis, A.; Whitford, D.K.; Ennis, R.P. Historical Examination of United States Intentional Mass School Shootings in the 20th and 21st Centuries: Implications for Students, Schools, and Society. Journal of Child and Family Studies 2018, 27, 2562–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milojević, S.; Janković, B. Osnovi policijske taktike, treće izmenjeno i dopunjeno izdanje [Basics of the Police Tactics, third revised edition]; Kriminalističko-policijski univerzitet: Beograd, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- RTS. Kolegijum MUP-a: Nalog za hitan prijem novih 1.200 policajaca, biće u školama i tokom sledeće školske godine [Collegium of the MUP: Order for the immediate admission of 1,200 new police officers, they will be in schools during the next school year as well]. Available online: https://www.rts.rs/lat/vesti/drustvo/5191069/kolegijum-mup-a-nalog-za-hitan-prijem-novih-1200-policajaca-bice-u-skolama-i-tokom-sledece-skolske-godine.html (accessed on 14.05.).

- May, D.C.; Rice, C.; Minor, K.I. An Examination of School Resource Officers’ Attitudes Regarding Behavioral Issues among Students Receiving Special Education Services. Current Issues in Education 2012, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Janković, B. The Role of the Police in Disasters Caused by Pandemic Infectious Diseases. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2021, 3, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyebkhan, G. Declaration of Helsinki: The ethical cornerstone of human clinical research. Indian Journal of Dermatology Venereology and Leprology 2003, 69, 245–247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Theriot, M.T.; Cuellar, M.J. School resource officers and students’ rights. Contemporary Justice Review 2016, 19, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).