Submitted:

08 September 2023

Posted:

11 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Predictive Variables

2.2.2. Outcome Variable

2.2.3. Mediating Variable

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

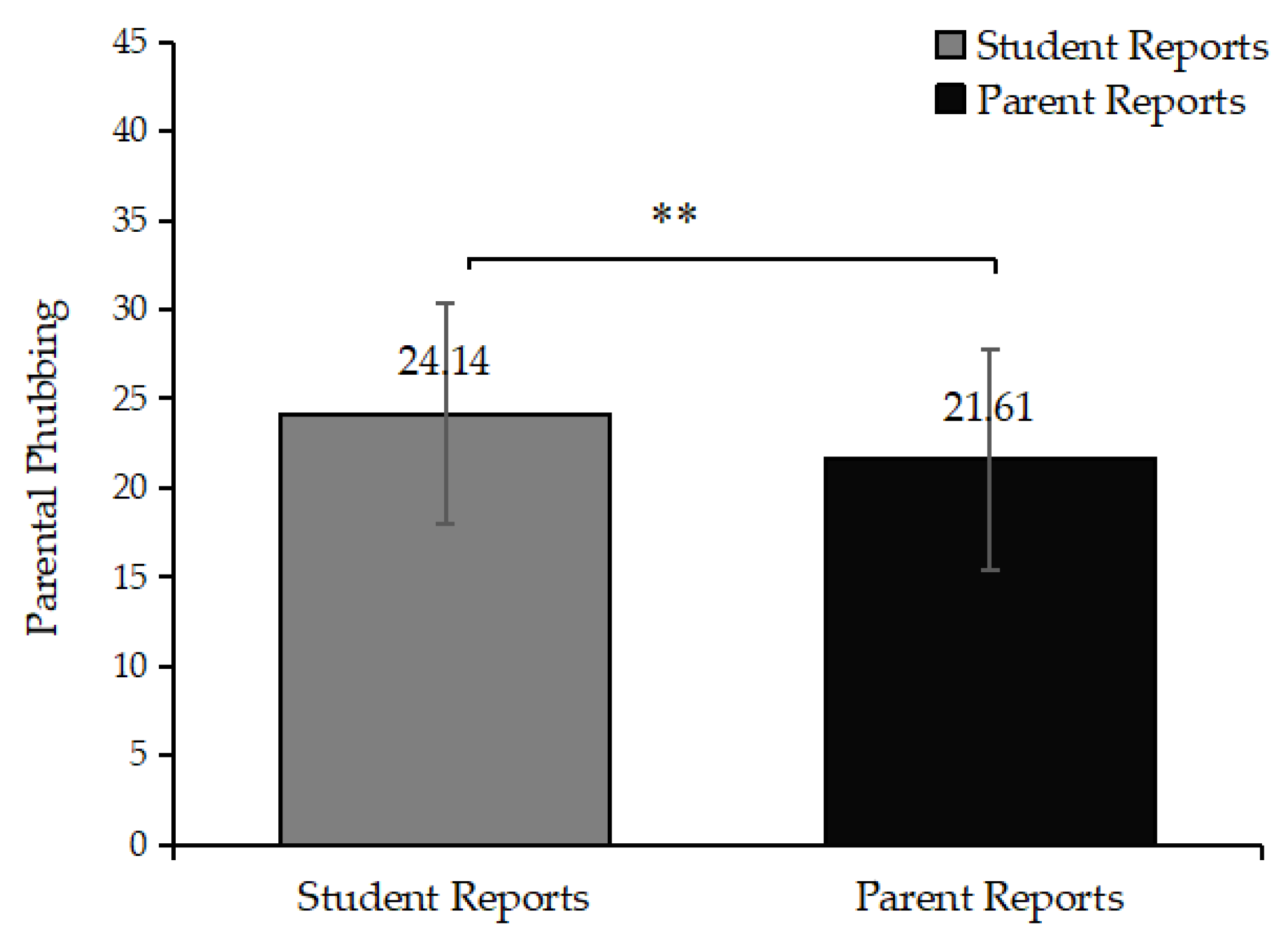

3.1. The Discrepancies in Adolescent–Parent Perceptions of the Parental Phubbing

3.2. Correlation Analysis

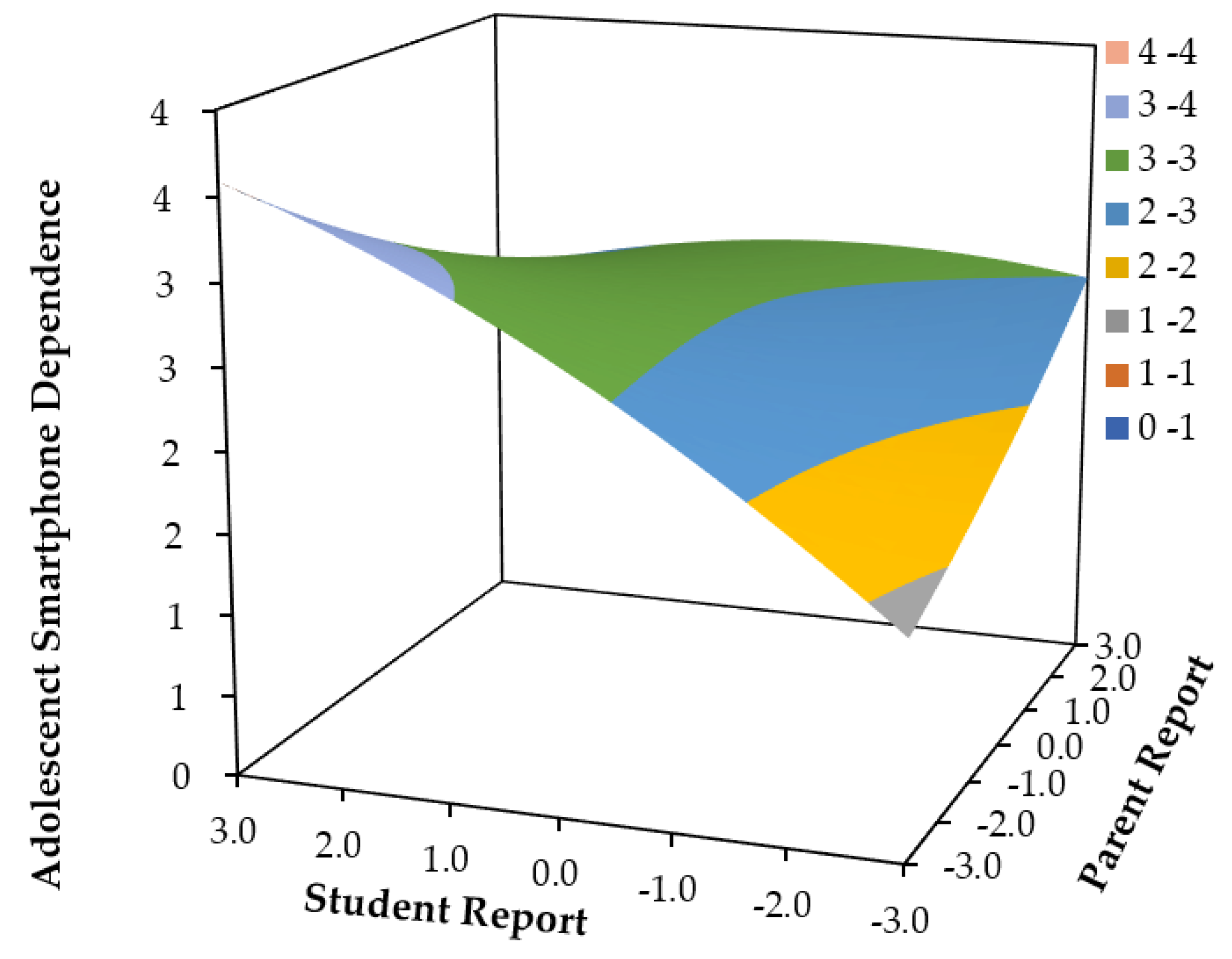

3.3. Predictive Effect of Parent-Child Perceptual Discrepancies in Parental phubbing on Adolescent Smartphone Dependence

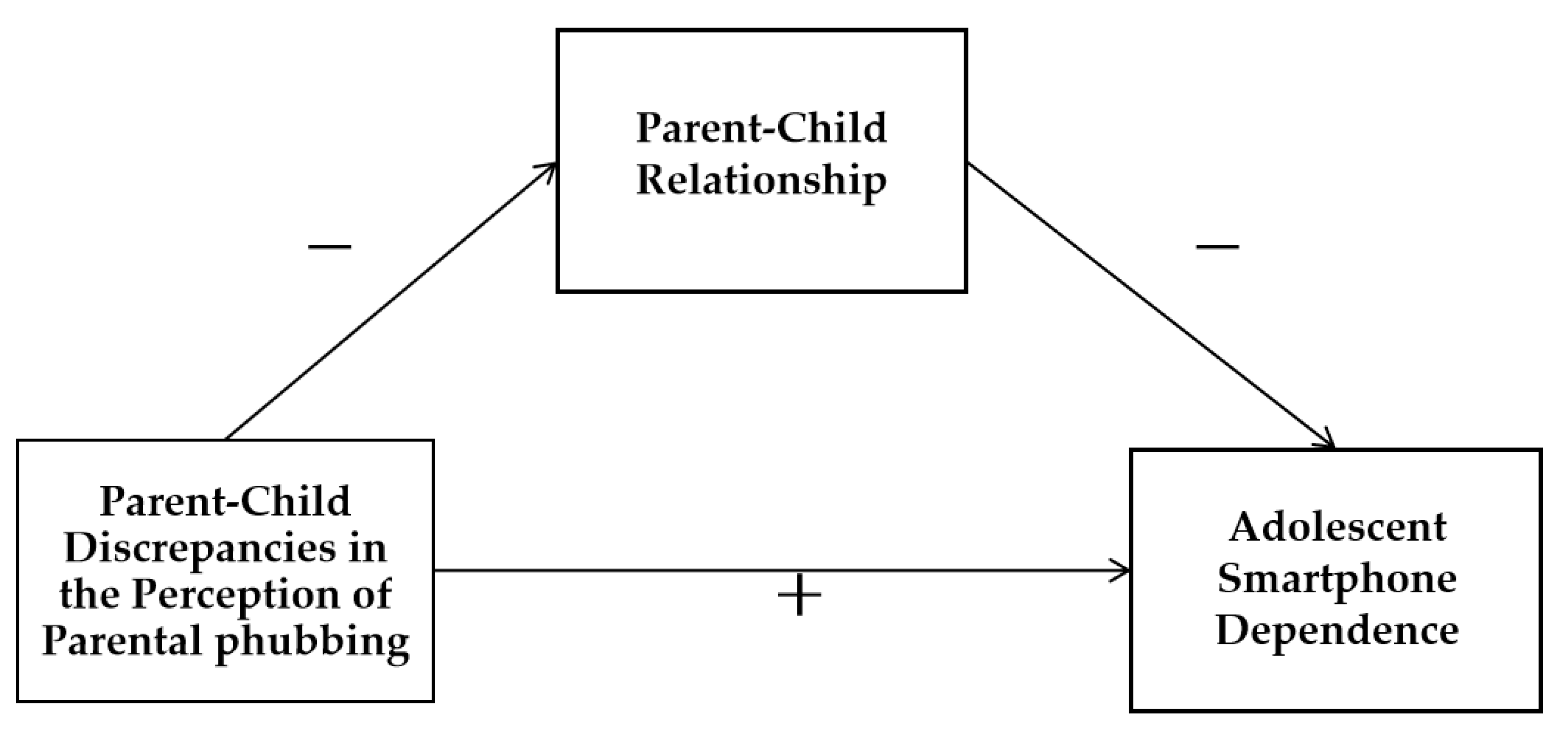

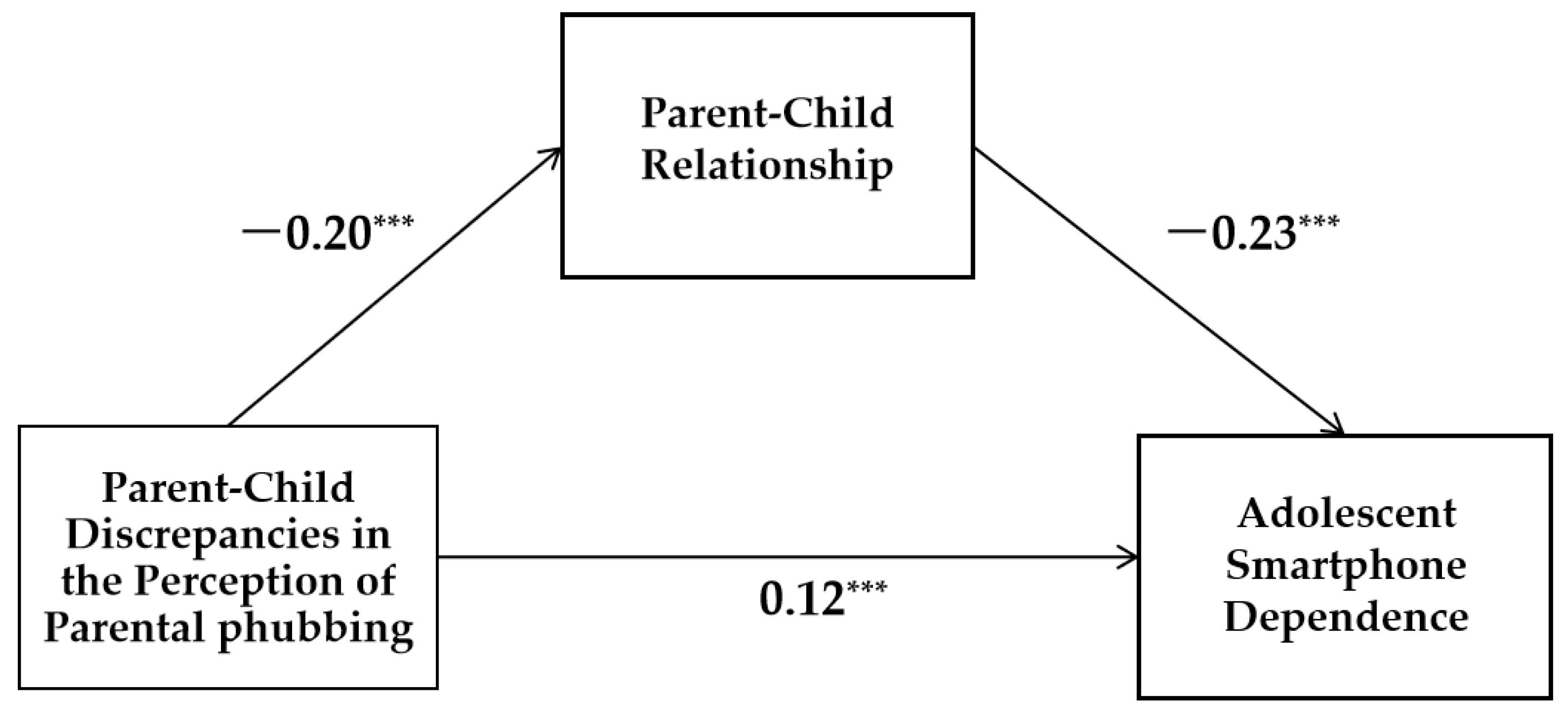

3.4. Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. There exists discrepancies in the perception of parental phubbing between parent and adolescent

4.2. The Impact of Parent-Child Discrepancies in the Perception of Parental phubbing on Adolescent Smartphone Dependence and the Mediating Role of Parent-Child Relationship

4.3. Limitations and Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, H., Ahn, H., Choi, S., Choi, W. The SAMS: Smartphone Addiction Management System and verification. J Med Syst 2014, 38, 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romer, D., Reyna, V. F., Satterthwaite, T. D. Beyond stereotypes of adolescent risk taking: Placing the adolescent brain in developmental context. Dev Cogn Neurosci 2017, 27, 19–34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anboucarassy, B., Begum, M. Effect of Use of Mobile Phone on Mental Health of Higher Secondary School Students. J Educ Psychol 2014, 8, 15–19.

- Vahedi, Z., Saiphoo, A. The association between smartphone use, stress, and anxiety: A meta-analytic review. Stress and Health 2018, 34, 347–358. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdem, E., Sezer Efe, Y. The smartphone addiction, peer relationships and loneliness in adolescents. L'Encephale 2021, 48, 490–495. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X., Yang, H., Wei, S., Wang, Y. Cross-sectional survey of smartphone addiction and its relationship with personality traits among medical students. Aust Psychiatry 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. J., Min, J. Y., Min, K. B., Lee, T. J., Yoo, S. Relationship among family environment, self-control, friendship quality, and adolescents' smartphone addiction in South Korea: Findings from nationwide data. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e190896. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J. Avoidance Attachment and Smartphone Addiction in Rural Secondary School Students. Acad J Humanit Soc Sci 2023, 6, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X., Chen, W., Zhu, X., He, D. Parents' phubbing increases Adolescents' Mobile phone addiction: Roles of parent-child attachment, deviant peers, and gender. Child Youth Serv Rev 2019, 105, 104426. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q., Dong, S., Zhang, Y. Does parental phubbing aggravates adolescent sleep quality problems? Front Psychol 2023, 14, 1094488. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y., Lin, L., Hu, R. Parental phubbing and academic burnout in adolescents: the role of social anxiety and self-control. Front Psychol 2023, 14, 1157209. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X., Qiao, Y. Parental Phubbing, Self-Esteem, and Suicidal Ideation among Chinese Adolescents: A Longitudinal Mediational Analysis. J Youth Adolesc 2022, 51, 2248–2260. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W., Tang, L., Shen, X., Niu, G., Shi, X., Jin, S.,... Yuan, Z. Parental Phubbing and Adolescent Depressive Symptoms during COVID-19: A Serial Meditating Model. Behav Sci 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Mi, Z., Cao, W., Diao, W., Wu, M., Fang, X. The relationship between parental phubbing and mobile phone addiction in junior high school students: A moderated mediation model. Front Psychol 2023, 14, 1117221. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., Ye, B., Luo, L., Yu, L. The Effect of Parent Phubbing on Chinese Adolescents' Smartphone Addiction During COVID-19 Pandemic: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2022, 15, 569–579. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Qiao, Y., Wang, S. Parental phubbing, problematic smartphone use, and adolescents' learning burnout: A cross-lagged panel analysis. J Affect Disord 2023, 320, 442–449. [CrossRef]

- Rohner, R. P. They Love Me, They love Me not: A worldwide Study of the Effects of Parental Acceptance and Rejection; HRAF Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1975; pp. 99–100. [Google Scholar]

- Rohner, R. P. Father Love and Child Development: History and Current Evidence. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 1998, 7, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohner, R. P. The Parental "Acceptance-Rejection Syndrome": Universal Correlates of Perceived Rejection. Am Psychol 2004, 59, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohner, R. P., Khaleque, A., Riaz, M. N., Khan, U., Sadeque, S., Laukkala, H. Agreement between Children's and Mothers' Perceptions of Maternal Acceptance and Rejection: A Comparative Study in Finland and Pakistan. Ethos 2005, 33, 367–377. [CrossRef]

- De Los Reyes, A., Goodman, K. L., Kliewer, W., Reid-Quiñones, K. The longitudinal consistency of mother-child reporting discrepancies of parental monitoring and their ability to predict child delinquent behaviors two years later. Journal of youth and adolescence 2010, 39, 1417–1430. [CrossRef]

- De Los Reyes, A., Kazdin, A. E. Measuring informant discrepancies in clinical child research. Psychol Assess 2004, 16, 330. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Los Reyes, A., Kazdin, A. E. Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: a critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychol bull 2005, 131, 483. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Los Reyes, A., Thomas, S. A., Goodman, K. L., Kundey, S. M. A. Principles underlying the use of multiple informants' reports. Annu Rev clin Psychol 2013, 9, 123–149. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Los Reyes, A., Ohannessian, C. M., Laird, R. D. Developmental Changes in Discrepancies Between Adolescents' and Their Mothers' Views of Family Communication. J Child Fam Stud 2016, 25, 790–797. [CrossRef]

- Guion, K., Mrug, S., Windle, M. Predictive Value of Informant Discrepancies in Reports of Parenting: Relations to Early Adolescents’ Adjustment. J Abnormal Child Psychol 2009, 37, 17–30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y., Kim, S. Y., Benner, A. D. Parent-Adolescent Discrepancies in Reports of Parenting and Adolescent Outcomes in Mexican Immigrant Families. J Youth Adolesc 2018, 47, 430–444. [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y., Kim, S. Y., Benner, A. D. Parent-Adolescent Discrepancies in Reports of Parenting and Adolescent Outcomes in Mexican Immigrant Families. J Youth Adolesc 2018, 47, 430–444. [CrossRef]

- Korelitz, K. E., Garber, J. Congruence of Parents' and Children's Perceptions of Parenting: A Meta-Analysis. J Youth Adolesc 2016, 45, 1973–1995. [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. The nature of a child’s tie to his mother. Int J Psychoanal 1958, 39, 350–373. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Q., Sun, R., Fu, E., Jia, G., Xiang, Y. Parent–child relationship and smartphone use disorder among Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of quality of life and the moderating role of educational level. Addictive Behaviors 2020, 101, 106065. [CrossRef]

- Oduor, E., Carman, N., William, O., Anthony, T., Niala, M., Melanie, T., Pourang, I. The Frustrations and Benefits of Mobile Device Usage in the Home when Co-Present with Family Members. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems, Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 4 June 2016. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C., Li, R., Luo, H., Li, S., Nie, Y. Parent-child Relationship and Smartphone Addiction among Chinese Adolescents: A Longitudinal Moderated Mediation Model. Addict Behav 2022, 130, 107304. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, J. A., David, M. E. My life has become a major distraction from my cell phone: Partner phubbing and relationship satisfaction among romantic partners. Comput Human Behav 2016, 54, 134–141. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, M., Wang Z., Ma, B. Reliability and Validity of Chinese Version of the Smartphone Addiction Scale in Adolescents. Chin J Clin Psychol 2019, 27, 959–964. [CrossRef]

- Buchnan, C. M., Maccoby, E. E., Dornbush, S. M. Caught between parents: Adolescents' experience in divorced homes. Child Dev 1991, 62, 1008–1029. [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J., Podsakoff, N. P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J Appl Psychol 2003, 88, 879–903. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. J Educ Meas 2013, 51, 335–337. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H., Zhu, L., Chen, W., Liu, Y., Zhang, X. J. Effect of harsh parenting on smartphone addiction: From the perspective of experience avoidance model. Chin J Clin Psychol 2021, 29, 501–505.

- Xie, X., Xie, J. Parental phubbing accelerates depression in late childhood and adolescence: A two-path model. J Adolesc 2020, 78, 43–52. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Ding, Q., Wang, Z. Why parental phubbing is at risk for adolescent mobile phone addiction: A serial mediating model. Child Youth Serv Rev 2021, 121, 105873. [CrossRef]

- Qu, J., Lei, L., Wang, X., Xie, X., Wang, P. Mother phubbing and adolescent cyberbullying: the mediating role of perceived mother acceptance and the moderating role of emotional stability. J Interpers Violence 2022, 37, NP9591–NP9612. [CrossRef]

- De Los Reyes, A., Ohannessian, C. M., Racz, S. J. Discrepancies Between Adolescent and Parent Reports About Family Relationships. Child Dev Perspect 2018, 13, 53–58. [CrossRef]

- De Los Reyes, A., Ohannessian, C. M., Laird, R. Developmental Changes in Discrepancies Between Adolescents' and Their Mothers' Views of Family Communication. J Child Fam Stud 2016, 25, 790–797. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Los Reyes, A. Introduction to the special section. More than measurement error: Discovering meaning behind informant discrepancies in clinical assessments of children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2011, 40, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juang, L. P., Syed, M., Takagi, M. Intergenerational discrepancies of parental control among Chinese American families: Links to family conflict and adolescent depressive symptoms. J Adolesc 2007, 30, 965–975. [CrossRef]

- Ohannessian, C. M. Discrepancies in adolescents’ and their mothers’ perceptions of the family and adolescent externalizing problems. Family Science 2012, 3, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Reyes, A., Lerner, M. D., Thomas, S. A., Daruwala, S., Goepel, K. Discrepancies between parent and adolescent beliefs about daily life topics and performance on an emotion recognition task. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2013, 41, 971–982. [CrossRef]

- Sarour, E. O., El Keshky, M. E. S. Deviant peer affiliation as a mediating variable in the relationship between family cohesion and adaptability and internet addiction among adolescents. Curr Psychol 2022, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Park, S. K., Kim, J. Y., Cho, C. B. Prevalence of Internet addiction and correlations with family factors among South Korean adolescents. Adolescence 2008, 43, 895–909.

- Chen, X., Liu, M., Li, D. Parental warmth, control, and indulgence and their relations to adjustment in Chinese children: a longitudinal study. J Fam Psychol 2000, 14, 401. [CrossRef]

- Khaleque, A., Rohner, R. P. Perceived parental acceptance-rejection and psychological adjustment: A meta-analysis of cross-cultural and intracultural studies. J Marriage Fam 2002, 64, 54–64. [CrossRef]

- Veneziano, R. A. The importance of paternal warmth. Cross-Cult Res 2003, 37, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G., Yao, L., Wu, L., Tian, Y., Xu, L., Sun, X. Parental phubbing and adolescent problematic mobile phone use: The role of parent-child relationship and self-control. Child Youth Serv Rev 2020, 116, 105247. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Gao, L., Yang, J., Zhao, F., Wang, P. Parental phubbing and adolescents’ depressive symptoms: Self-esteem and perceived social support as moderators. J Youth Adolesc 2020, 49, 427–437. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, M. E., Roberts, J. A. Phubbed and alone: Phone snubbing, social exclusion, and attachment to social media. J Assoc Consum Res 2017, 2, 155–163. [CrossRef]

- Borelli, J. L., Compare, A., Snavely, J. E., Decio, V. Reflective functioning moderates the association between perceptions of parental neglect and attachment in adolescence. Psychoanal Psychol 2015, 32, 23. [CrossRef]

- Matejevic, M., Jovanovic, D., Ilic, M. Patterns of family functioning and parenting style of adolescents with depressive reactions. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2015, 185, 234–239. [CrossRef]

- Terry, D. J. Investigating the relationship between parenting styles and delinquent behavior. McNair Scholars J 2004, 8, 11. [Google Scholar]

| M(SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parents perceive their own phubbing | 21.61(6.16) | - | ||||

| 2. Students perceive parental phubbing | 24.14(7.59) | 0.42** | - | |||

| 3. Perception discrepancies of parental phubbing | 0(1.07) | -0.05 | 0.15** | - | ||

| 4. Parent-child relationship | 3.48(0.86) | -0.15** | -0.41** | -0.22** | - | |

| 5. Adolescent smartphone dependence | 2.42(0.88) | 0.12** | 0.32** | 0.16** | -0.25** | - |

| Regression Coefficient | Response Surface Analysis Coefficients | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

b0 (SE) |

b1 (SE) |

b2 (SE) |

b3 (SE) |

b4 (SE) |

b5 (SE) |

a1 (SE) |

a2 (SE) |

a3 (SE) |

a4 (SE) |

|

| Adolescent smartphone dependence | ||||||||||

| Parental phubbing | 2.56*** (0.05) |

0.17*** (-0.3) |

-0.01 (0.03) |

-0.03 (0.02) |

-0.07* (0.03) |

-0.01 (0.03) |

0.15*** (0.05) |

-0.09 (0.03) |

0.18* (0.07) |

0.05 (0.06) |

| Predictor | Criterion: Parent-child relationship | Criterion: Adolescent smartphone dependence | |||||||

| β | SE | t | [LLCI, ULCI] | β | SE | t | [LLCI, ULCI] | ||

| Grade | -0.14 | 1.13 | -3.95** | [-6.68,-2.29] | -0.06 | 2.06 | -1.53 | [-7.24,0.85] | |

| Perception discrepancies of parental phubbing | -0.2 | 0.53 | -5.36*** | [-3.85,-1.80] | 0.12 | 0.97 | 3.27*** | [1.25,5.06] | |

| Parent-child relationship | -0.23 | 0.07 | -6.21*** | [-0.56,-0.29] | |||||

| R2 | 0.07 | 0.08 | |||||||

| F | 27.08*** | 19.83*** | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).