Submitted:

11 September 2023

Posted:

12 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

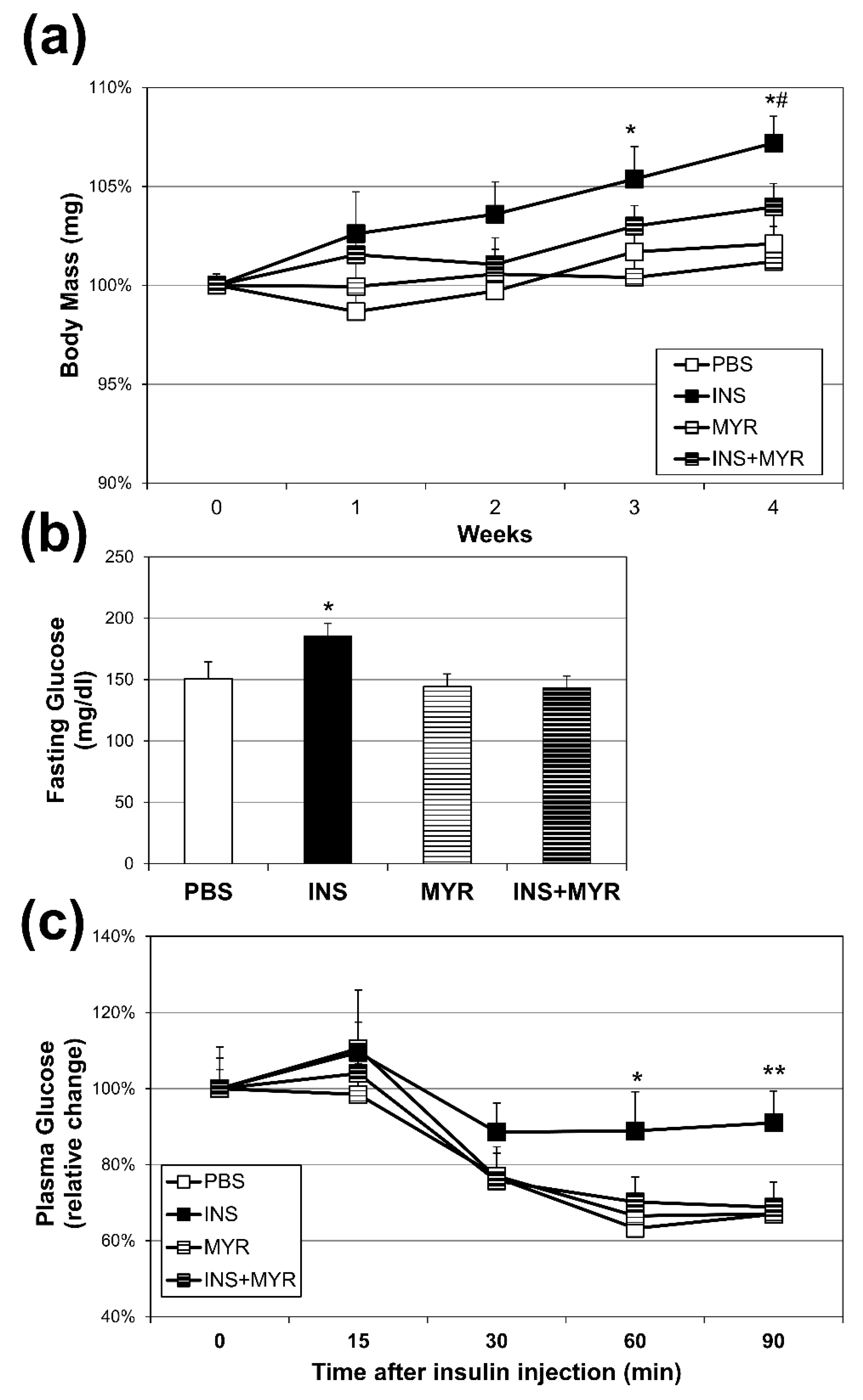

2.1. Chronic Insulin Injections Increase Body Weight and Reduce Insulin Tolerance in Male and Female ApoE4 Mice

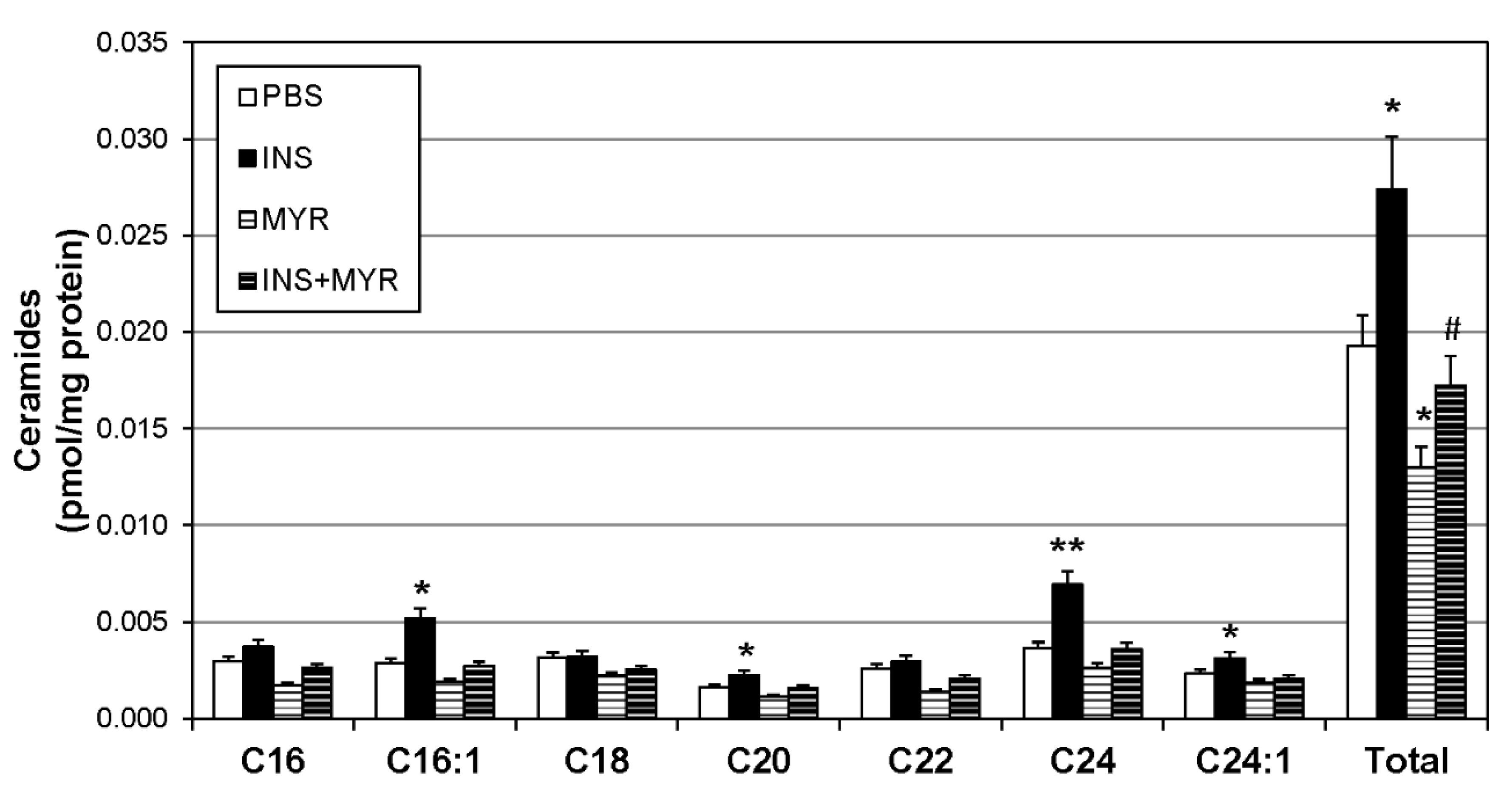

2.2. Insulin Increases Brain Ceramide Accrual in Male and Female ApoE4 Mice

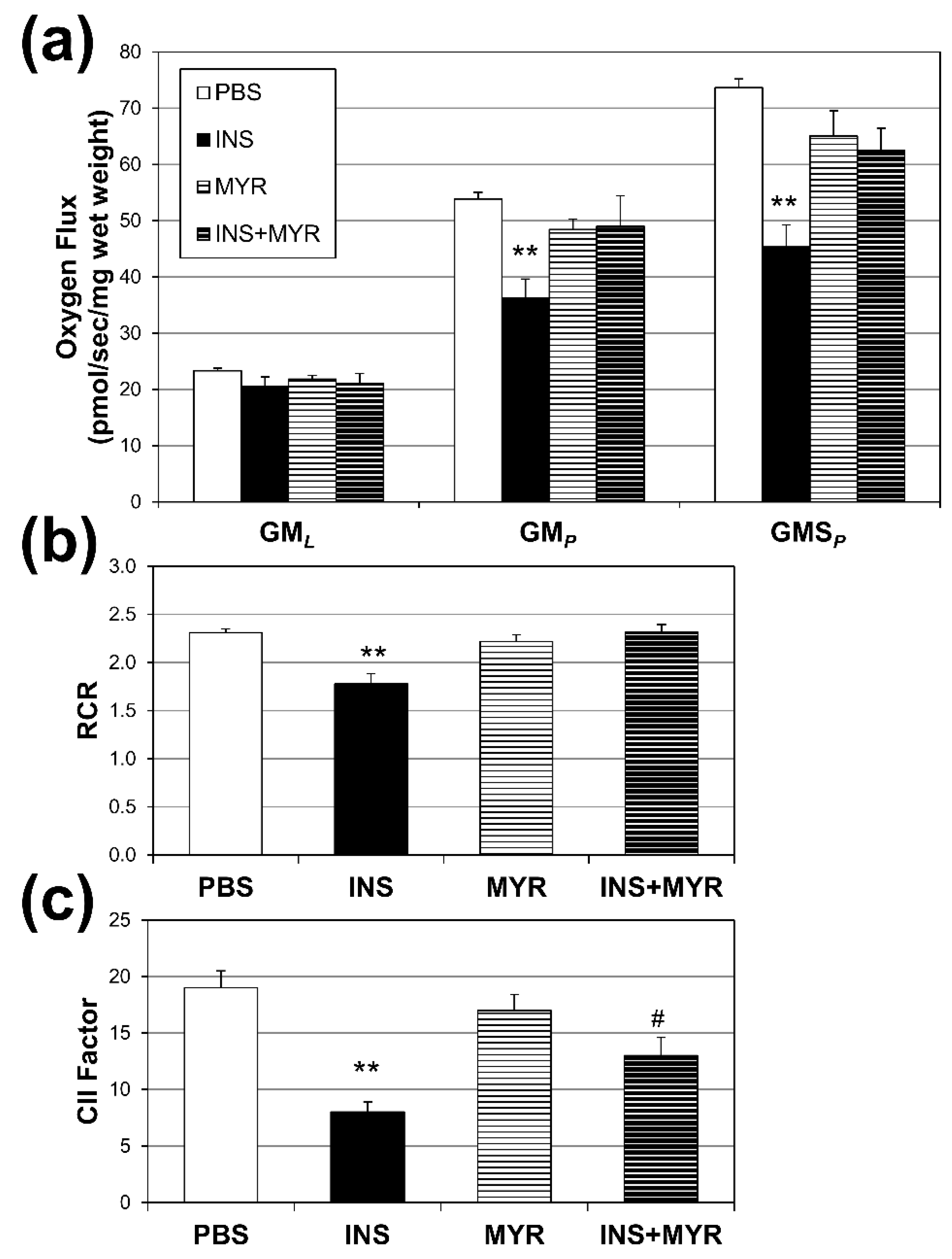

2.3. Insulin Disrupts Mitochondrial Function in Brain Tissue of Male and Female ApoE4 Mice

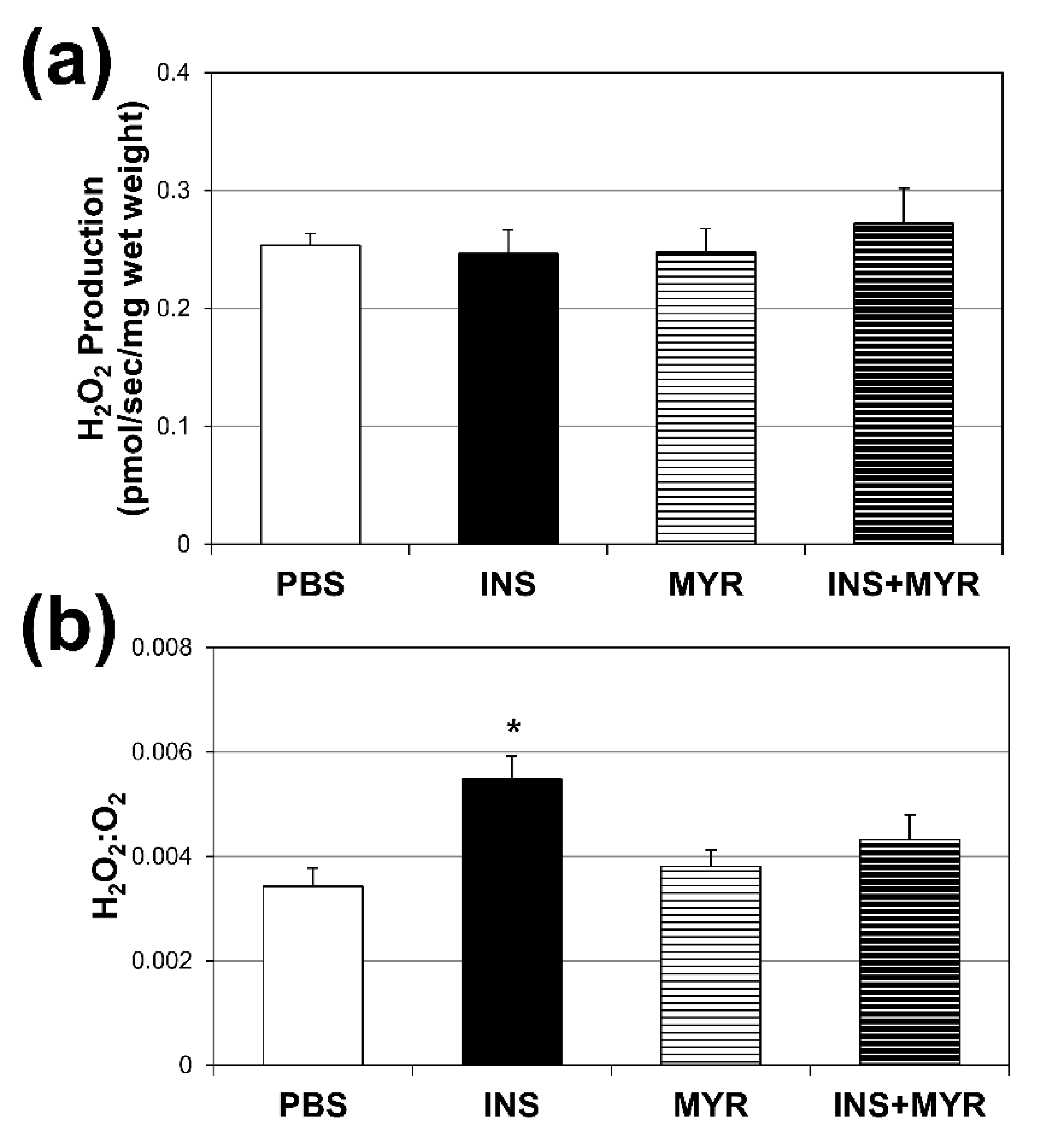

2.4. Chronic Insulin Injections Direct Brain O2 Use Towards H2O2 Production in Male and Female ApoE4 Mice

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Insulin Tolerance Test

4.3. Lipid Nalysis

4.4. Mitochondrial Respirometry

4.5. H2O2 Emissions

4.6. Statistics

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shanik, M.H.; Xu, Y.; Skrha, J.; Dankner, R.; Zick, Y.; Roth, J. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia: is hyperinsulinemia the cart or the horse? Diabetes care 2008, 31, S262–S268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saklayen, M.G. The Global Epidemic of the Metabolic Syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep 2018, 20, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, C.K.; Hevener, A.L.; Barnard, R.J. Metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance: underlying causes and modification by exercise training. Compr Physiol 2013, 3, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, S.L.; MacLean, J.E.; Hoey, L.; Horwood, L.; Barrowman, N.; Foster, B.; Hadjiyannakis, S.; Legault, L.; Bendiak, G.N.; Kirk, V.G.; et al. Insulin Resistance and Hypertension in Obese Youth With Sleep-Disordered Breathing Treated With Positive Airway Pressure: A Prospective Multicenter Study. J Clin Sleep Med 2017, 13, 1039–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornfeldt, K.E.; Tabas, I. Insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, and atherosclerosis. Cell Metab 2011, 14, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crone, C. Facilitated transfer of glucose from blood into brain tissue. The Journal of physiology 1965, 181, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hom, F.G.; Goodner, C.J.; Berrie, M.A. A (3H) 2-deoxyglucose method for comparing rates of glucose metabolism and insulin responses among rat tissues in vivo: validation of the model and the absence of an insulin effect on brain. Diabetes 1984, 33, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerozissis, K. Brain insulin: regulation, mechanisms of action and functions. Cellular and molecular neurobiology 2003, 23, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueckler, M. Facilitative glucose transporters. European journal of biochemistry 1994, 219, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havrankova, J.; Roth, J.; BROWNSTEIN, M. Insulin receptors are widely distributed in the central nervous system of the rat. Nature 1978, 272, 827–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, D.; Williams, G. Insulin receptors are widely distributed in human brain and bind human and porcine insulin with equal affinity. Diabetic Medicine 1997, 14, 1044–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S.-L.; Chen, C.-M.; Cline, H.T. Insulin receptor signaling regulates synapse number, dendritic plasticity, and circuit function in vivo. Neuron 2008, 58, 708–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2022 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimer's & Dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association 2022.

- Neth, B.J.; Craft, S. Insulin Resistance and Alzheimer's Disease: Bioenergetic Linkages. Front Aging Neurosci 2017, 9, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusisto, J.; Koivisto, K.; Mykkanen, L.; Helkala, E.L.; Vanhanen, M.; Hanninen, T.; Kervinen, K.; Kesaniemi, Y.A.; Riekkinen, P.J.; Laakso, M. Association between features of the insulin resistance syndrome and Alzheimer's disease independently of apolipoprotein E4 phenotype: cross sectional population based study. BMJ 1997, 315, 1045–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampath, D.; Sathyanesan, M.; Newton, S.S. Cognitive dysfunction in major depression and Alzheimer's disease is associated with hippocampal-prefrontal cortex dysconnectivity. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Sokolowska, E.; Blachnio-Zabielska, A. The role of ceramides in insulin resistance. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2019, 10, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerschmidt, P.; Brüning, J.C. Contribution of specific ceramides to obesity-associated metabolic diseases. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2022, 79, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzanne, M. Insulin resistance and Alzheimer’s disease. BMB reports 2009, 42, 475. [Google Scholar]

- Filippov, V.; Song, M.A.; Zhang, K.; Vinters, H.V.; Tung, S.; Kirsch, W.M.; Yang, J.; Duerksen-Hughes, P.J. Increased ceramide in brains with Alzheimer's and other neurodegenerative diseases. J Alzheimers Dis 2012, 29, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jazvinšćak Jembrek, M.; Hof, P.R.; Šimić, G. Ceramides in Alzheimer’s disease: key mediators of neuronal apoptosis induced by oxidative stress and Aβ accumulation. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubhra Chakrabarti, S.; Bir, A.; Poddar, J.; Sinha, M.; Ganguly, A.; Chakrabarti, S. Ceramide and sphingosine-1-phosphate in cell death pathways: relevance to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Current Alzheimer Research 2016, 13, 1232–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyn-Cook Jr, L.E.; Lawton, M.; Tong, M.; Silbermann, E.; Longato, L.; Jiao, P.; Mark, P.; Wands, J.R.; Xu, H.; de la Monte, S.M. Hepatic Ceramide May Mediate Brain Insulin Resistance and Neurodegeneration in Type 2 Diabetes and Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 2009, 16, 715–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutler, R.G.; Kelly, J.; Storie, K.; Pedersen, W.A.; Tammara, A.; Hatanpaa, K.; Troncoso, J.C.; Mattson, M.P. Involvement of oxidative stress-induced abnormalities in ceramide and cholesterol metabolism in brain aging and Alzheimer's disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2004, 101, 2070–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, M.E.; Tippetts, T.S.; Anderson, M.C.; Holub, Z.E.; Moulton, E.R.; Swensen, A.C.; Prince, J.T.; Bikman, B.T. Insulin increases ceramide synthesis in skeletal muscle. J Diabetes Res 2014, 2014, 765784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, A.E.; Tippetts, T.S.; Bikman, B.T. Insulin treatment increases myocardial ceramide accumulation and disrupts cardiometabolic function. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2015, 14, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchsinger, J.A.; Tang, M.-X.; Shea, S.; Mayeux, R. Hyperinsulinemia and risk of Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2004, 63, 1187–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatz, M.; Reynolds, C.A.; Fratiglioni, L.; Johansson, B.; Mortimer, J.A.; Berg, S.; Fiske, A.; Pedersen, N.L. Role of genes and environments for explaining Alzheimer disease. Archives of general psychiatry 2006, 63, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sienski, G.A.-O.; Narayan, P.A.-O.; Bonner, J.A.-O.; Kory, N.A.-O.; Boland, S.A.-O.; Arczewska, A.A.; Ralvenius, W.A.-O.; Akay, L.A.-O.; Lockshin, E.A.-O.; He, L.; et al. APOE4 disrupts intracellular lipid homeostasis in human iPSC-derived glia. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Chaurasia, B.; Summers, S.A. Ceramides–lipotoxic inducers of metabolic disorders. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 2015, 26, 538–550. [Google Scholar]

- Hodson, A.E.; Tippetts, T.S.; Bikman, B.T. Insulin treatment increases myocardial ceramide accumulation and disrupts cardiometabolic function. Cardiovascular Diabetology 2015, 14, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontiroli, A.E.; Alberetto, M.; Pozza, G. Patients with insulinoma show insulin resistance in the absence of arterial hypertension. Diabetologia 1992, 35, 294–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, R.R.; Gumbiner, B.; Ditzler, T.; Wallace, P.; Lyon, R.; Glauber, H.S. Intensive Conventional Insulin Therapy for Type II Diabetes: Metabolic effects during a 6-mo outpatient trial. Diabetes Care 1993, 16, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Prato, S.; Leonetti, F.; Simonson, D.C.; Sheehan, P.; Matsuda, M.; DeFronzo, R.A. Effect of sustained physiologic hyperinsulinaemia and hyperglycaemia on insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity in man. Diabetologia 1994, 37, 1025–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bikman, B.T.; Summers, S.A. Ceramides as modulators of cellular and whole-body metabolism. The Journal of clinical investigation 2011, 121, 4222–4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, G.; Wang, J.; Rasul, A.; Anwar, H.; Imran, A.; Qasim, M.; Zafar, S.; Kamran, S.K.S.; Razzaq, A.; Aziz, N.; et al. Role of cholesterol and sphingolipids in brain development and neurological diseases. Lipids in Health and Disease 2019, 18, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Nevado-Holgado, A.; Whiley, L.; Snowden, S.G.; Soininen, H.; Kloszewska, I.; Mecocci, P.; Tsolaki, M.; Vellas, B.; Thambisetty, M. Association between plasma ceramides and phosphatidylcholines and hippocampal brain volume in late onset Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 2017, 60, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielke, M.M.; Bandaru, V.V.R.; Haughey, N.J.; Rabins, P.V.; Lyketsos, C.G.; Carlson, M.C. Serum sphingomyelins and ceramides are early predictors of memory impairment. Neurobiology of aging 2010, 31, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielke, M.M.; Haughey, N.J.; Bandaru, V.V.R.; Schech, S.; Carrick, R.; Carlson, M.C.; Mori, S.; Miller, M.I.; Ceritoglu, C.; Brown, T. Plasma ceramides are altered in mild cognitive impairment and predict cognitive decline and hippocampal volume loss. Alzheimer's & Dementia 2010, 6, 378–385. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, E.R.; Himali, J.J.; Xanthakis, V.; Duncan, M.S.; Schaffer, J.E.; Ory, D.S.; Peterson, L.R.; DeCarli, C.; Pase, M.P.; Satizabal, C.L. Circulating ceramide ratios and risk of vascular brain aging and dementia. Annals of clinical and translational neurology 2020, 7, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czubowicz, K.; Jęśko, H.; Wencel, P.; Lukiw, W.J.; Strosznajder, R.P. The role of ceramide and sphingosine-1-phosphate in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Molecular neurobiology 2019, 56, 5436–5455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, J.; Parnham, M.J.; Geisslinger, G.; Schiffmann, S. Ceramides as novel disease biomarkers. Trends in molecular medicine 2019, 25, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teitsdottir, U.D.; Halldorsson, S.; Rolfsson, O.; Lund, S.H.; Jonsdottir, M.K.; Snaedal, J.; Petersen, P.H. Cerebrospinal fluid C18 ceramide associates with markers of Alzheimer’s disease and inflammation at the pre-and early stages of dementia. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 2021, 81, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison-Barnes, A.; Johnson, S.; Gudzune, K. Trends in obesity prevalence among adults aged 18 through 25 years, 1976-2018. JAMA 2021, 326, 2073–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, M.; Tippetts, T.S.; Anderson, M.; Holub, Z.; Moulton, E.; Swensen, A.; Prince, J.; Bikman, B. Insulin increases ceramide synthesis in skeletal muscle. Journal of Diabetes Research 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesta, D.; Gnaiger, E. High-Resolution Respirometry: OXPHOS Protocols for Human Cells and Permeabilized Fibers from Small Biopsies of Human Muscle. In Mitochondrial Bioenergetics: Methods and Protocols; Palmeira, C.M., Moreno, A.J., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2012; pp. 25–58. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.E.; Tippetts, T.S.; Brassfield, E.S.; Tucker, B.J.; Ockey, A.; Swensen, A.C.; Anthonymuthu, T.S.; Washburn, T.D.; Kane, D.A.; Prince, J.T.; et al. Mitochondrial fission mediates ceramide-induced metabolic disruption in skeletal muscle. Biochemical Journal 2013, 456, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jheng, H.-F.; Tsai, P.-J.; Guo, S.-M.; Kuo, L.-H.; Chang, C.-S.; Su, I.-J.; Chang, C.-R.; Tsai, Y.-S. Mitochondrial Fission Contributes to Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Insulin Resistance in Skeletal Muscle. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2012, 32, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napa, K.; Baeder, A.C.; Witt, J.E.; Rayburn, S.T.; Miller, M.G.; Dallon, B.W.; Gibbs, J.L.; Wilcox, S.H.; Winden, D.R.; Smith, J.H.; et al. LPS from P. gingivalis Negatively Alters Gingival Cell Mitochondrial Bioenergetics. Int J Dent 2017, 2017, 2697210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).