Submitted:

12 September 2023

Posted:

13 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Variables

2.3.1. Dependent Variables

2.3.2. Independent Variables

2.3.3. Covariables

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

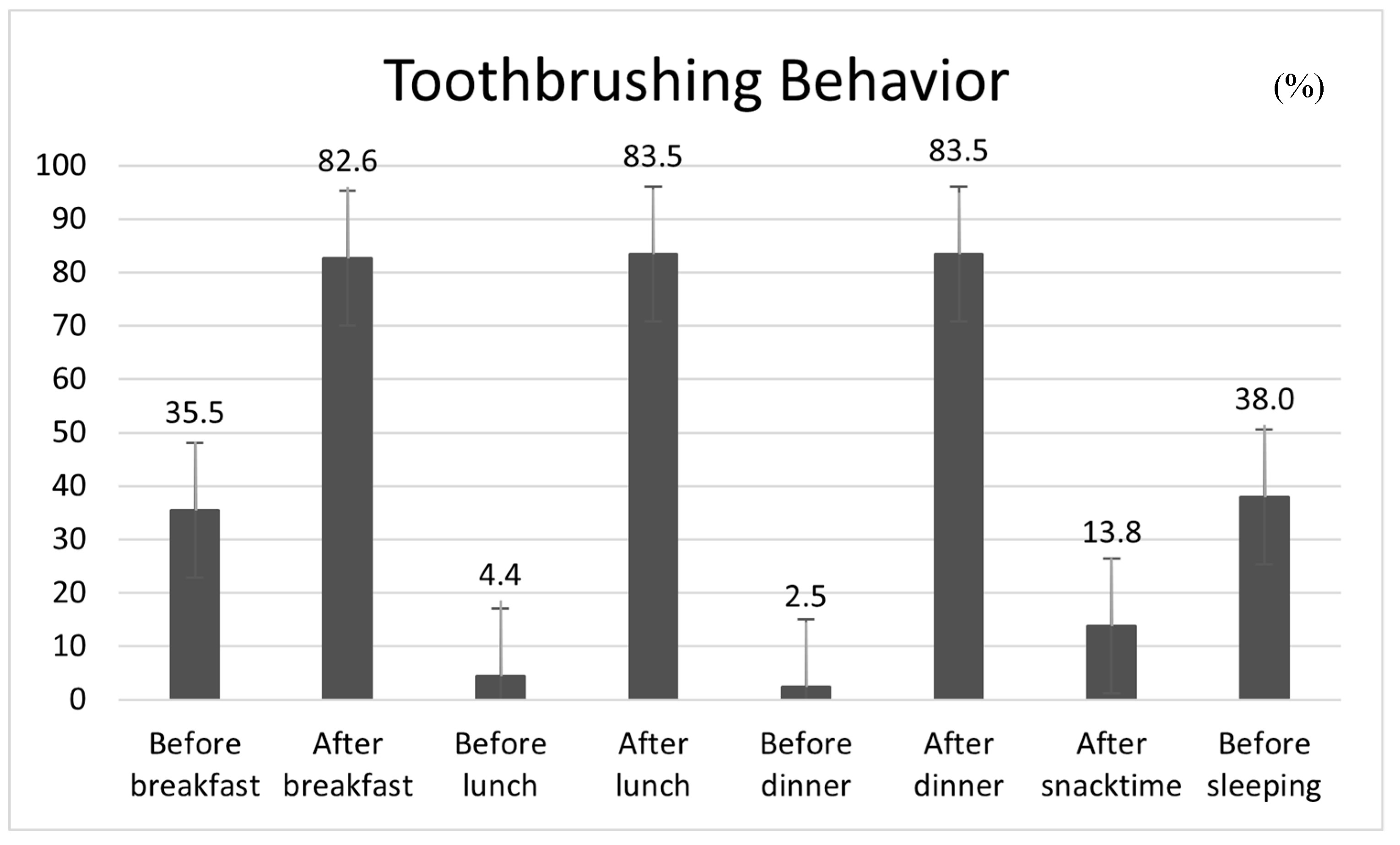

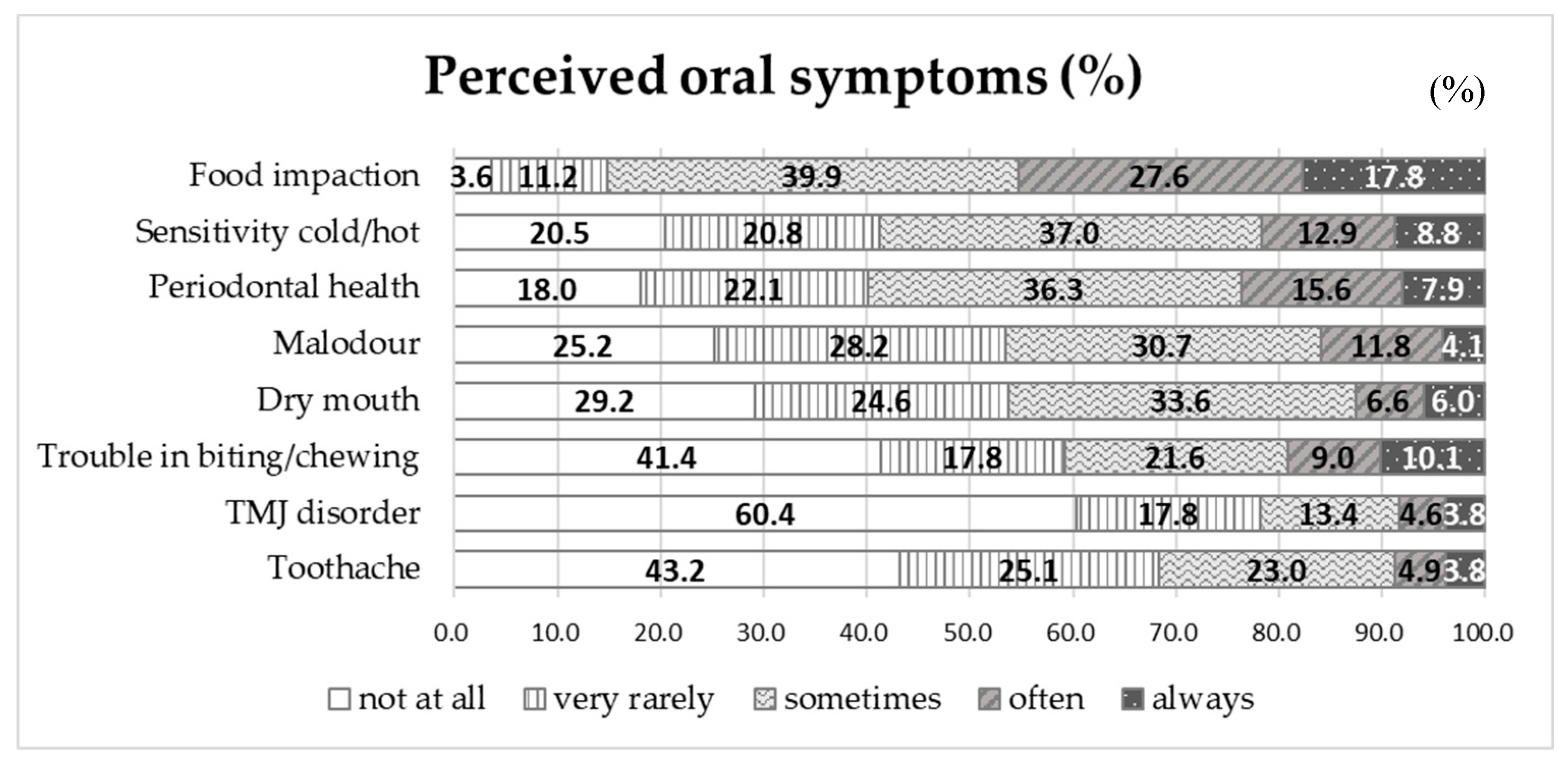

3.1. Toothbrushing Behaviour and Perceived Oral Symptoms in Male Inmates

3.2. OHIP-14 According to the General Characteristics of Male Inmates

3.3. Correlation between Perceived Oral Symptoms and Self-Esteem and OHIP-14 in Male Inmates

3.4. Factors Related to OHIP-14 in Male Inmates

4. Discussion

Clinical strengths, Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ryu, D.-Y.; Song, K.-S.; Han, S.-Y. Oral health condition, recognition, and practice in prisoners. J. Dent. Hyg. Sci. 2015, 15, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeon, S.-J.; Roh, Y.-J.; Kim, A.-S.; Jung, Y.- J. Health and medical services for inmates in Korean correctional facilities. KICJ. 2008, 12, 1–228. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, Y. Survey on the Right to Health in Detention Facilities, 2016. National Human Rights Commission of Korea 2017.

- Darnaud, C.; Thomas, F.; Pannier, B.; Danchin, N.; Bouchard, P. Oral health and blood pressure: The IPC Cohort. Am. J. Hypertens. 2015, 28, 1257–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salcedo-Rocha, A.L.; Garca-de-Alba-Garcia, J.E.; Velsquez-Herrera, J.G.; Barba-Gonzlez, E.A. Oral health: Validation of a questionnaire of self-perception and self-care habits in diabetes mellitus 2, hypertensive and obese patients. The UISESS-B scale. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2011, 16, e834–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangiry, L.; Bagheri, R.; Darabi, F.; Sarbakhsh, P.; Sistani, M.M.N.; Ponnet, K. Oral health status and associated lifestyle behaviors in a sample of Iranian adults: An exploratory household survey. BMC Oral Health 2020, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arantes, R.; Santos, R.V.; Frazo, P. Oral health in transition: the case of indigenous peoples from Brazil. Int. Dent. J. 2010, 60, 235–240. [Google Scholar]

- Banyai, D.; Vegh, D.; Vegh, A.; Ujpal, M.; Payer, M.; Biczo, Z.; Rzsa, N. Oral health status of children living with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferruzzi, L.P.D.C.; Davi, L.R.; Lima, D.C.B.D.; Tavares, M.; Castro, A.M.D. Oral health-related quality of life of athletes with disabilities: a cross sectional study. J. Biosci. 2021, 37, e37008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, G.D.; Spencer, A.J. Development and evaluation of the oral health impact profile. Community Dent. Health 1994, 11, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Slade, GD. Derivation and validation of a short-form oral health impact profile. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 1997, 25, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.-J.; Yoon, M.-S. Relationship of depression, stress, and self-esteem with oral health-related quality of life of middle-aged women. J. Korean Soc. Dent. Hyg. 2015, 15, 825–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkrishna, A.; Singh, K.; Sharma, A.; Parkar, S.M.; Oberoi, G. Oral health among prisoners of district jail, Haridwar, Uttarakhand, India-A cross-sectional study. Rev. Esp. Sanid. Penit. 2022, 24, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraes, L.R.; Duarte de Aquino, L.C.; Cruz, D.T.d.; Leite, I.C.G. Self-perceived impact of oral health on the quality of life of women deprived of their liberty. Int. J. Dent. 2021, 2021, 5520652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, G.H.; Mendona, I.; Michel-Crosato, E.; Moyss, S.J.; Moyss, S.T.; Werneck, R.I. Impact of oral conditions on the quality of life of incarcerated women in Brazil. Health Care Women Int. 2019, 40, 776–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, R.; Al-Sulaimi, A.; Fadaak, A.; Balhaddad, A.; AlKhalfan, A.; El Tantawi, M.; Al-Ansari, A. Oral health amongst male inmates in Saudi prisons compared with that of a sample of the general male population. S. Afr. Dent. J. 2017, 72, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casarin, M.; Nolasco, W.d.S.; Colussi, P.R.G.; Piardi, C.C.; Weidlich, P.; Rösing, C.K.; Muniz, F.W.M.G. Prevalence of tooth loss and associated factors in institutionalized adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Cien. Saude Colet. 2021, 26, 2635–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhadra, T. Prevalence of dental caries and oral hygiene status among juvenile prisoners in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2017, 18, 991–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evensen, K.B.; Bull, V.H. Oral health in prison: An integrative review. Int. J. Prison. Health 2023, 19, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evensen, K.B.; Bull, V.H.; Ness, L. A health promotion intervention to improve oral health of prisoners: Results from a pilot study. Int. J. Prison. Health 2021, 17, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, I.; Park, K.; Park, H.-K. Prevalence of dental caries and associated factors of detention center inmates in South Korea compared with Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) respondents: a retrospective study. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.-U.; Yoo, J.-H.; Choi, B.-H.; Sul, S.-H.; Kim, H.-R.; Mo, D.-Y.; Kim, J.-B. Conservative infection control on acute pericoronitis in mandibular third molar patients referred from the prison. J. Korean Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010, 36, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-H. A research on recognition of oral health based on oral health education for adolescents in some reformatories. J. Dent. Hyg. Sci. 2007, 7, 187–191. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Y.-J.; Jeong, S.-Y.; Kang, B.-J.; Baek, K.-W. Oral health status and self-perceived oral health status of students in juvenile protection education institutions. J. Korean Acad. Pediatr. Dent. 2009, 36, 539–549. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical Research Information System(CRIS). Available online: https://cris.nih.go.kr/cris/index.jsp (accessed on 13 Jul 2023).

- Bana, K.F.M.A.; Shadab, S.; Hakeem, S.; Ilyas, F. Comparing oral health-related quality of life (OHIP-14) and masticatory efficiency with complete denture treatment. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2021, 30, 694–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.-I.; Han, S.-J. Factors which affect the oral health-related quality of life of workers. J. Dent. Hyg. Sci. 2013, 13, 480–486. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, United states, 1965, 16-36. [CrossRef]

- Nasiriziba, F.; Saati, M.; Haghani, H. Correlation between self-efficacy and self-esteem in patients with an intestinal stoma. Br. J. Nurs. 2020, 29, S22–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.-H.; Choi, Y.-H.; Jeong, S.-H.; Cho, H.-J.; Son, C.-K.; Jeong, S.-H. Korea national children’s oral health survey. National Center for Medical Information and Knowledge (NCMIK), Korea, 2018.

- Public Health England. Survey of prison dental services England, Wales and Northern Ireland 2017 to 2018. Public Health England, 2022.

- The Scottish Government. Oral Health Improvement and Dental Services in Scottish Prisons. The Scottish Government, 2015.

- Billa, A.L.; Sukhabogi, J.R.; Doshi, D.; Jummala, S.; Turaga, S.S. Correlation of self-esteem with oral hygiene behaviour and oral health status among adult dental patients. Ann. Ig. 2023, 35, 534–545. [Google Scholar]

- Ibigbami, O.I.; Folayan, M.O.; Oginni, O.; Lusher, J.; Sam-Agudu, N.A. Moderating effects of resilience and self-esteem on associations between self-reported oral health problems, quality of oral health, and mental health among adolescents and adults in Nigeria. PLoS one 2023, 18, e0285521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melbye, E.L. Dimensional structure of the OHIP-14 and associations with self-report oral health-related variables in home-dwelling Norwegians aged 70+. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2023, 81, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022 Community health survey [Internet]. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022. Available online: https://chs.kdca.go.kr/chs/ststs/statsMain.do (accessed on 15 Jul 2023).

- Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 2013~2015. Available online: https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/sub01/sub01_02.do#s2_01 (accessed on 15 Jul 2023).

- The Korean Law Information Center. Act on the Execution of Penalties and Treatment of Inmates. The Korean Law Information Center, 2022 Available online: Act on Execution of Sentences and Treatment of Prisoners (law.go.kr) (accessed on 15 Jul 2023).

- Park, C.-S.; Kim, I.-J. Oral health behaviour according to perceived oral symptoms in the elderly. J. Korean Soc. Dent. Hyg. 2016, 16, 955–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.-H.; Lee, J.-M.; Jang, K.-W. Effect of oral health status and work loss on oral health-related quality of life of non-medical hospital workers. J. Converg. Inf. Technol. 2022, 12, 163–173. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, A.-J.; Kang, E.-J. A study on the oral symptoms and oral health-related quality of life (OHIP-14) of industrial workers. J. Dent. Hyg. Sci. 2014, 14, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, B.; Jeong, S.-R.; Jang, J.-Y.; Kim, K.-Y. Health-related quality of life by oral health behaviour and oral health status for the middle-aged people. J. Korean Soc. Dent. Hyg. 2015, 15, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.-S.; Choi, J.-S. The effect of health status on general quality of life and oral health related quality of life in the middle-aged adults. J. Dent. Hyg. Sci. 2012, 12, 624–633. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S.-U.; Nam, I.-S. Oral health impact profile (OHIP) according to the oral health behaviour of foreign workers. J. Korean Soc. Dent. Hyg. 2015, 15, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.-S. Relationship of oral health status and oral health care to the quality of life in patients of dental hospitals and clinics. J. Dent. Hyg. Sci. 2015, 15, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-L.; Kim, J.-H.; Jang, J.-H. Relationship between dental checkups and unmet dental care needs in Korean adults. J. Korean Soc. Dent. Hyg. 2020, 20, 581–591. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, J.-H.; Kim, J.-L.; Kim, J.-H. Associations between dental checkups and unmet dental care needs: An examination of cross-sectional data from the seventh Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2016–2018). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.-J.; Kim, M.-G. The effect of oral function on the quality of kife of Korean adults by age group. Korean J. Heal. Serv. Manag. 2016, 10, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-R.; Choi, J.-S. Relationship of self-perceived symptoms of periodontal disease to quality of life in adults. J. Dent. Hyg. Sci. 2012, 12, 115–121. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.-Y.; Kim, G.-P.; Yu, B.-C. Relationship between periodontal disease and quality of life. J. Korean Soc. Dent. Hyg. 2013, 13, 835–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.-S.; Jang, J.-H. Relationship between health risk behaviors, oral health-related quality of life (OHIP-14) and happiness in soldiers. J. Korean Soc. Dent. Hyg. 2017, 17, 1159–1169. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.-L.; Kwag, J.-S.; Choi, J.-H. Correlation and influencing factors on oral health awareness, oral health behaviour, self-esteem and OHIP-14 in childcare teachers. J. Korean Soc. Dent. Hyg. 2015, 15, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grecu, A.G.; Balazsi, R.; Dudea, D.; Mesaro, A.; Strmbu, M.; Dumitracu, D.L. Oral health related quality of life and self-esteem in a general population. Med. Pharm. Rep. 2019, 92, S65–S72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-N.; Lee, M.-R. Main cause of influencing oral health impact profile (OHIP) and self-esteem of orthodontic patients. J. Korean Soc. Dent. Hyg. 2010, 10, 513–522. [Google Scholar]

- Gobic, M.B.; Kralj, M.; Harmicar, D.; Cerovic, R.; Maricic, B.M.; Spalj, S. Dentofacial deformity and orthognathic surgery: Influence on self-esteem and aspects of quality of life. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2021, 49, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). Available online: https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=IV-4&chapter=4&clang=_en (accessed on 21 Sep 2022).

- Korean Ministry of Government Legislation. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/ Laws/Constitution of the Republic of Korea (accessed on 04 Nov 2022).

- Chun, J.-H. A study on correctional medical treatment for disabled prisoners and sick prisoners. J. Welf. Corr. 2021, 73, 175–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-G.; Sun, J.-G.; Park, I.-K.; Kang, H.-H.; Kim, S.-Y.; Sohn, M.-S. Correctional health care delivery system and prisoners’ human rights. Korean J. Med. L. 2009, 17, 121–150. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.-K. Medical treatment for prisoners. Correct. Rev. 2010, 48, 73–104. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Division | N (%) | OHIP-14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | p-Value* | |||

| Age (years) | 20–29 a | 37 (10.2) | 46.86 ± 10.57 | < 0.001 |

| 30–39 ab | 80 (22.0) | 43.60 ± 10.84 | ||

| 40–49 bc | 85 (23.4) | 39.84 ± 13.39 | ||

| 50–59 c | 99 (27.3) | 36.15 ± 12.07 | ||

| ≥ 60 c | 62 (17.1) | 36.39 ± 11.28 | ||

| EDT (for last year) | Yes | 110 (30.3) | 38.26 ± 13.39 | 0.265 |

| No | 246 (67.8) | 40.59 ± 12.06 | ||

| Don’t know | 7 (1.9) | 39.71 ± 4.79 | ||

| EDE (for last year) | Yes | 145 (39.8) | 41.19 ± 12.04 | 0.247 |

| No | 214 (59.0) | 38.96 ± 12.70 | ||

| Don’t know | 5 (1.4) | 40.60 ± 5.59 | ||

| Toothbrushing time (min) | < 1 a | 51 (14.01) | 37.12 ± 12.37 | 0.02 |

| 1 to less than 2 ab | 126 (34.62) | 38.10 ± 13.06 | ||

| 2 to less than 3 b | 121 (33.24) | 41.87 ± 10.84 | ||

| ≥ 3 b | 66 (18.13) | 41.73 ± 13.12 | ||

| Use of fluoride toothpaste | Use | 173 (47.92) | 39.90 ± 11.89 | 0.432 |

| No use | 73 (20.22) | 38.60 ± 11.67 | ||

| Don’t know | 115 (31.86) | 40.97 ± 13.15 | ||

| Chewing discomfort | Tofu & Ricea | 21 (5.8) | 25.81 ± 13.04 | < 0.001 |

| Applea | 9 (2.5) | 26.22 ± 15.47 | ||

| Kimchiab | 36 (10.0) | 29.06 ± 12.80 | ||

| Meatbc | 61 (16.9) | 37.30 ± 90.4 | ||

| Dried squidbc | 29 (8.1) | 36.45 ± 11.53 | ||

| Hard candyc | 204 (56.7) | 45.46 ± 8.80 | ||

| Subjective health | Strongly disagreea | 56 (15.38) | 26.41 ± 13.86 | < 0.001 |

| Disagreeb | 93 (25.55) | 36.47 ± 10.17 | ||

| Neutralbc | 123 (33.79) | 43.22 ± 8.95 | ||

| Agreec | 82 (22.53) | 46.89 ± 9.38 | ||

| Strongly agreec | 10 (2.75) | 48.10 ± 12.77 | ||

| Subjective oral health | Strongly disagreea | 78 (21.49) | 27.77 ± 13.58 | < 0.001 |

| Disagreeb | 130 (35.81) | 38.68 ± 9.78 | ||

| Neutralbc | 117 (32.23) | 46.01 ± 8.00 | ||

| Agreebc | 34 (9.37) | 49.26 ± 7.57 | ||

| Strongly agreec | 4 (1.10) | 54.75 ± 1.89 | ||

| Self-esteem | High | 49 (13.39) | 41.10 ± 15.64 | 0.547 |

| Usual | 252 (68.85) | 40.12 ± 11.97 | ||

| Low | 65 (17.76) | 38.65 ± 10.55 | ||

| Total | 376 (100.0) | 39.90 ± 12.38 | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Food impaction | 1 | |||||||||

| 2. Sensitivity cold/hot | 0.492** | 1 | ||||||||

| 3. Periodontal health | 0.434** | 0.566** | 1 | |||||||

| 4. Malodour | 0.373** | 0.507** | 0.633** | 1 | ||||||

| 5. Dry mouth | 0.316** | 0.446** | 0.499** | 0.622** | 1 | |||||

| 6. Trouble biting/chewing | 0.366** | 0.570** | 0.555** | 0.520** | 0.514** | 1 | ||||

| 7. TMJ disorder | 0.176** | 0.340** | 0.386** | 0.431** | 0.426** | 0.447** | 1 | |||

| 8. Toothache | 0.318** | 0.509** | 0.548** | 0.536** | 0.520** | 0.628** | 0.583** | 1 | ||

| 9. Self-esteem | 0.018 | 0.008 | -0.050 | -0.114* | -0.063 | -0.040 | -0037 | -0.023 | 1 | |

| 10. OHIP-14*** | -0.338** | -0.546** | -0.570** | -0.552** | -0.523** | -0.749** | -0.488** | -0.649** | 0.057 | 1 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | ß | t | p-Value* | B | SE | ß | t | p-Value* | |

| (Constant) | 20.705 | 2.998 | 6.905 | < 0.001 | 53.394 | 3.381 | 15.790 | < 0.001 | ||

| Age | -0.093 | 0.038 | -0.099 | -2.436 | 0.015 | -0.138 | 0.031 | -0.146 | -4.412 | < 0.001 |

| Subjective health | 2.259 | 0.597 | 0.200 | 3.785 | < 0.001 | 1.482 | 0.471 | 0.131 | 3.146 | 0.002 |

| Subjective oral health | 3.493 | 0.676 | 0.278 | 5.168 | < 0.001 | 0.755 | 0.570 | 0.060 | 1.326 | 0.186 |

| Chewing discomfort (ref. = Tofu & Rice) | ||||||||||

| Apple | -2.735 | 3.569 | -0.034 | -0.766 | 0.444 | -4.808 | 2.809 | -0.060 | -1.712 | 0.088 |

| Kimchi | 3.100 | 2.400 | 0.077 | 1.292 | 0.197 | 0.273 | 1.908 | 0.007 | 0.143 | 0.886 |

| Meat | 8.629 | 2.207 | 0.270 | 3.910 | < 0.001 | 3.196 | 1.778 | 0.100 | 1.798 | 0.073 |

| Squid | 5.675 | 2.548 | 0.126 | 2.228 | 0.027 | 1.279 | 2.041 | 0.028 | 0.627 | 0.531 |

| Candy | 12.665 | 2.080 | 0.522 | 6.089 | < 0.001 | 4.255 | 1.768 | 0.175 | 2.407 | 0.017 |

| Perceived oral symptoms | ||||||||||

| Food impaction | 0.212 | 0.423 | 0.018 | 0.502 | 0.616 | |||||

| Sensitivity cold/hot | 0.400 | 0.429 | 0.039 | 0.931 | 0.353 | |||||

| Periodontal health | -0.936 | 0.463 | -0.089 | -2.021 | 0.044 | |||||

| Malodour | -1.423 | 0.481 | -0.131 | -2.957 | 0.003 | |||||

| Dry mouth | -0.008 | 0.425 | -0.001 | -0.018 | 0.985 | |||||

| Trouble biting/chewing | -2.735 | 0.429 | -0.307 | -6.376 | < 0.001 | |||||

| TMJ disorder | -1.086 | 0.409 | -0.099 | -2.656 | 0.008 | |||||

| Toothache | -1.687 | 0.491 | -0.154 | -3.439 | 0.001 | |||||

| F (p-Value) | 44.754 (< 0.001) | 51.631 (< 0.001) | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.511 | 0.711 | ||||||||

| Adj. R2 | 0.499 | 0.698 | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).