Submitted:

12 September 2023

Posted:

14 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

Statistical analysis

3. Results

General data of patients with AMI

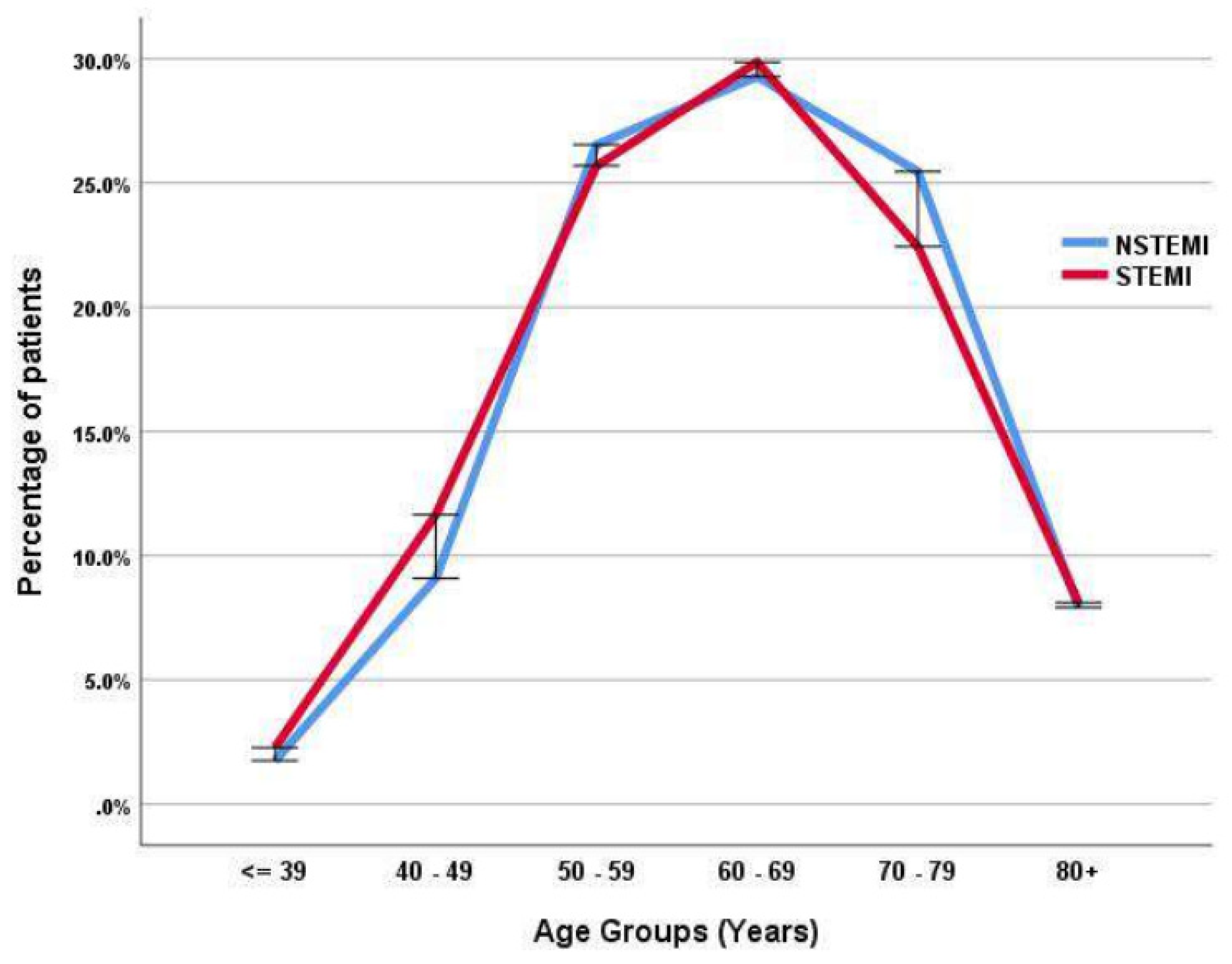

STEMI versus NSTEMI patients

Risk factors predicting STEMI and NSTEMI

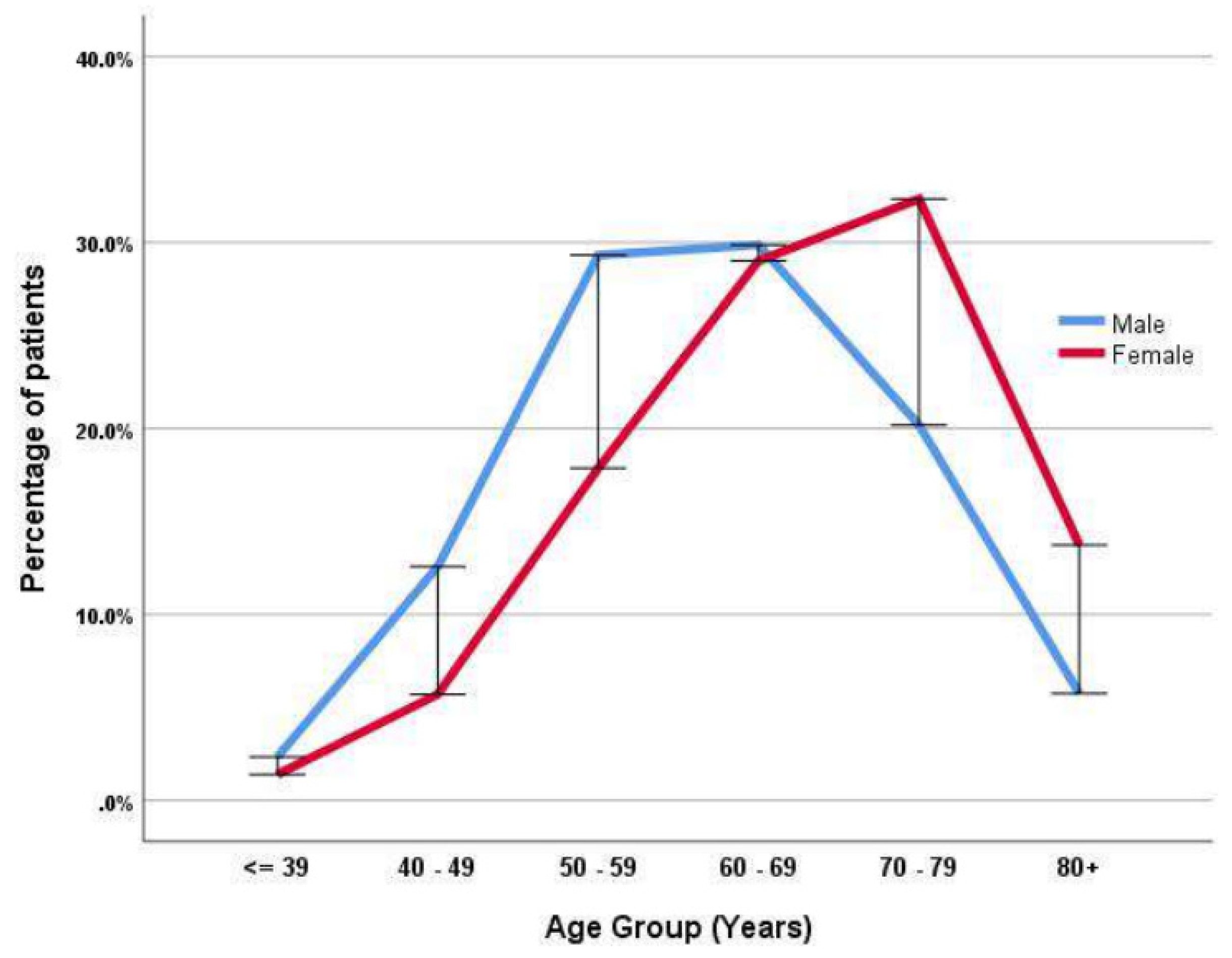

The age and gender in patients with acute AMI

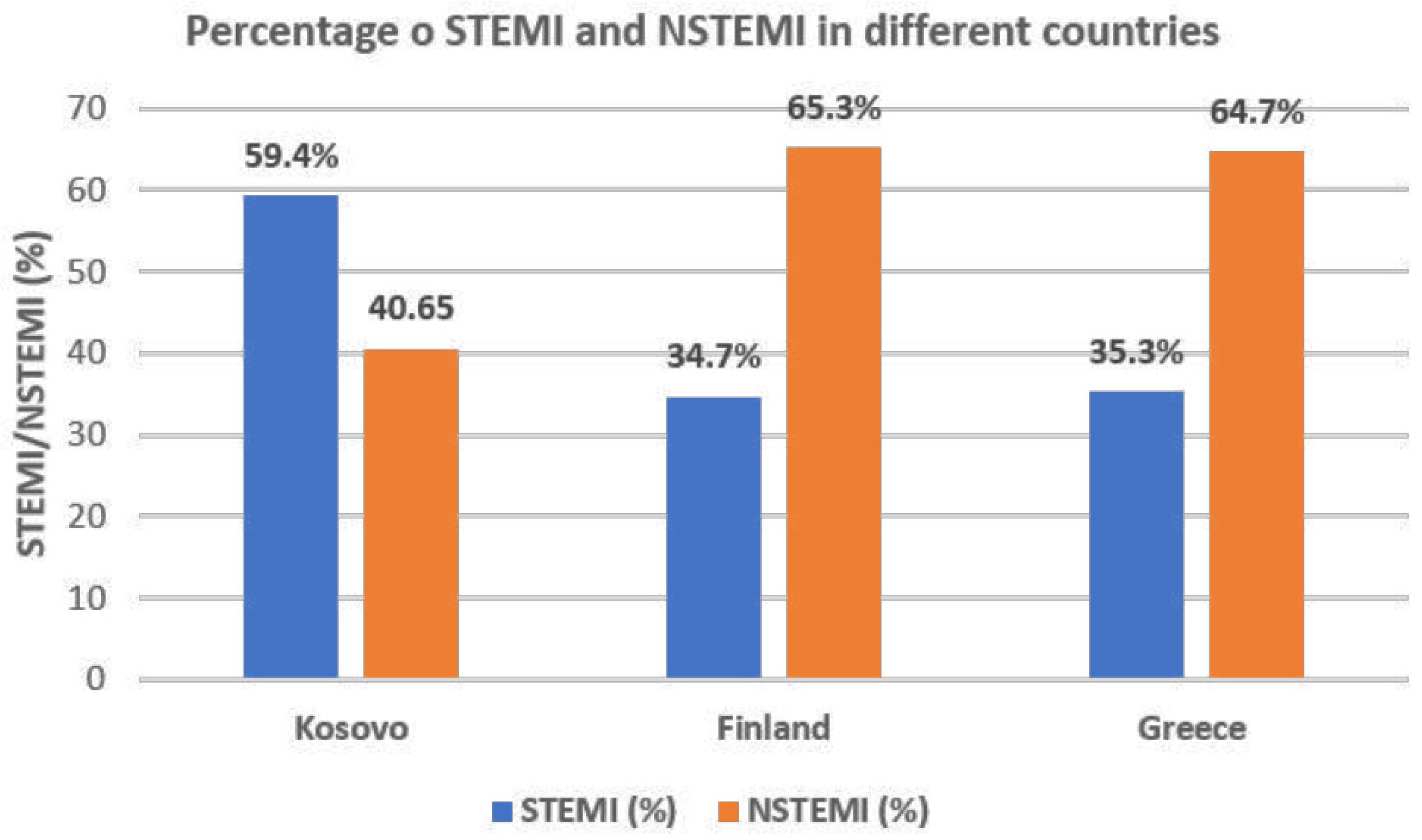

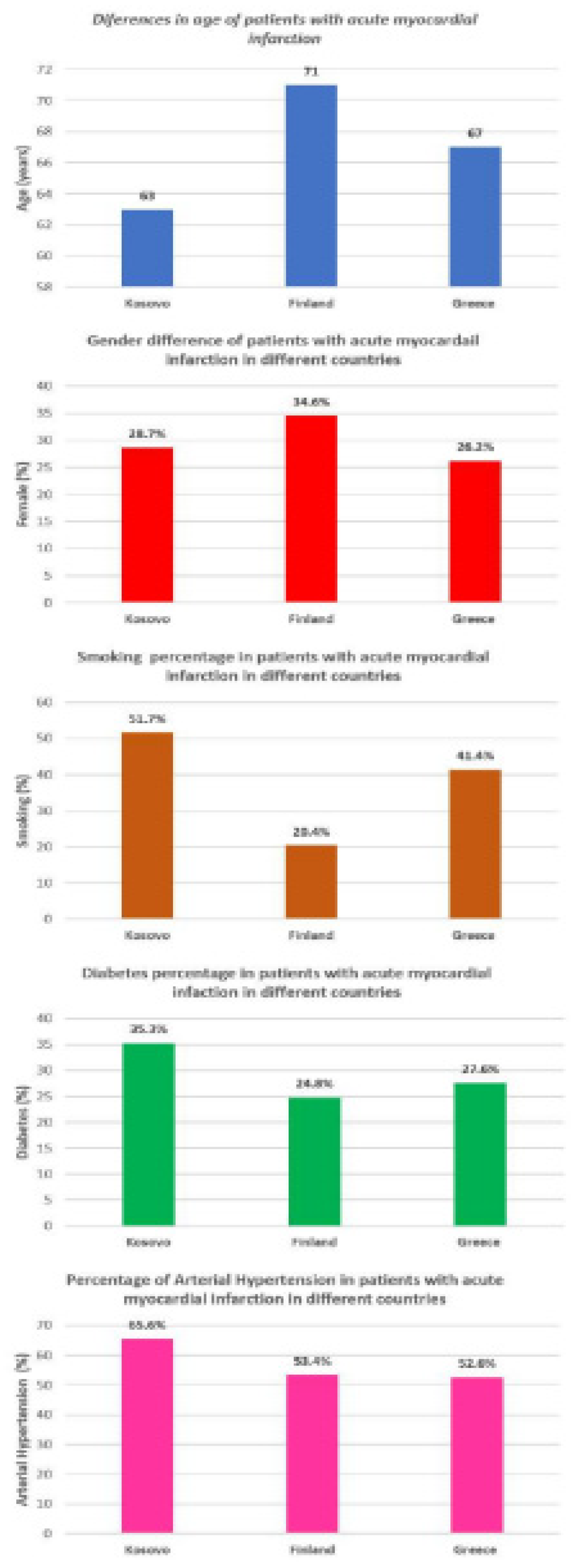

Comparison between acute MI patients in Kosovo and North and South Europe

4. Discussion

Findings:

Data interpretation:

Clinical Implications:

Limitations:

Conclusion:

Acknowledgments

References

- GBD 2017 Mortality Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality and life expectancy, 1950-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1684–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.A.; Hashim, M.J.; Mustafa, H.; Baniyas, M.Y.; Al Suwaidi, S.K.B.M.; Alkatheeri, R.; Alblooshi, F.M.K.; Almatrooshi, M.E.A.H.; Alzaabi, M.E.H.; Al Darmaki, R.S.; et al. Global Epidemiology of Ischemic Heart Disease: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Cureus 2020, 12, e9349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowbar, A.N.; Gitto, M.; Howard, J.P.; Francis, D.P.; Al-Lamee, R. Mortality from Ischemic Heart Disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019, 12, e005375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seligman, B.; Vedanthan, R.; Fuster, V. Acute coronary syndromes in low- and middle-income countries: Moving forward. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 217, S10–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; et al. GBD-NHLBI-JACC Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases Writing Group. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990-2019: Update from the GBD 2019 Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2982–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeymer, U.; Ludman, P.; Danchin, N.; Kala, P.; Laroche, C.; Sadeghi, M.; Caporale, R.; Shaheen, S.M.; Legutko, J.; Iakobsishvili, Z.; et al. Reperfusion therapies and in-hospital outcomes for ST-elevation myocardial infarction in Europe: the ACVC-EAPCI EORP STEMI Registry of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. Hear. J. 2021, 42, 4536–4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poloński, L.; Gasior, M.; Gierlotka, M.; Kalarus, Z.; Cieśliński, A.; Dubiel, J.S.; Gil, R.J.; Ruzyłło, W.; Trusz-Gluza, M.; Zembala, M.; Opolski, G. Polish Registry of Acute Coronary Syndromes (PL-ACS). Characteristics, treatments and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes in Poland. Kardiol Pol. 2007, 65, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mohanan, P.P.; Mathew, R.; Harikrishnan, S.; Krishnan, M.N.; Zachariah, G.; Joseph, J.; Eapen, K.; Abraham, M.; Menon, J.; Thomas, M.; et al. Presentation, management, and outcomes of 25 748 acute coronary syndrome admissions in Kerala, India: results from the Kerala ACS Registry. Eur. Hear. J. 2012, 34, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Insam, C.; Paccaud, F.; Marques-Vidal, P. Trends in hospital discharges, management and in-hospital mortality from acute myocardial infarction in Switzerland between 1998 and 2008. BMC Public Heal. 2013, 13, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanssen, M.; Cottin, Y.; Khalife, K.; Hammer, L.; Goldstein, P.; Puymirat, E.; Mulak, G.; Drouet, E.; Pace, B.; Schultz, E.; et al. French Registry on Acute ST-elevation and non ST-elevation Myocardial Infarction 2010. FAST-MI 2010. Hear. 2012, 98, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchis-Gomar, F.; Perez-Quilis, C.; Leischik, R.; Lucia, A. Epidemiology of coronary heart disease and acute coronary syndrome. Ann. Transl. Med. 2016, 4, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collet, J.P.; Thiele, H.; Barbato, E.; Barthélémy, O.; Bauersachs, J.; Bhatt, D.L.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2021, 42, 1289–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludman, P.; Zeymer, U.; Danchin, N.; Kala, P.; Laroche, C.; Sadeghi, M.; Caporale, R.; Shaheen, S.M.; Legutko, J.; Iakobishvili, Z.; et al. Care of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: an international analysis of quality indicators in the acute coronary syndrome STEMI Registry of the EURObservational Research Programme and ACVC and EAPCI Associations of the European Society of Cardiology in 11 462 patients. Eur. Hear. Journal. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2022, 12, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, D.D.; Gore, J.; Yarzebski, J.; Spencer, F.; Lessard, D.; Goldberg, R.J. Recent Trends in the Incidence, Treatment, and Outcomes of Patients with STEMI and NSTEMI. Am. J. Med. 2011, 124, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyers, H.P.; Bracey, A.; Lee, D.; Lichtenheld, A.; Li, W.J.; Singer, D.D.; Kane, J.A.; Dodd, K.W.; Meyers, K.E.; Thode, H.C.; et al. Comparison of the ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) vs. NSTEMI and Occlusion MI (OMI) vs. NOMI Paradigms of Acute MI. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 60, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- André, R.; Bongard, V.; Elosua, R.; Kirchberger, I.; Farmakis, D.; Häkkinen, U.; et al. International differences in acute coronary syndrome patients' baseline characteristics, clinical management and outcomes in Western Europe: the EURHOBOP study. Heart. 2014, 100, 1201–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajraktari, G.; Thaqi, K.; Pacolli, S.; Gjoka, S.; Rexhepaj, N.; Daullxhiu, I.; Sylejmani, X.; Elezi, S. In-hospital mortality following acute myocardial infarction in Kosovo: a single center study. Ann Saudi Med. 2008, 28, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khraishah, H.; Alahmad, B.; Alfaddagh, A.; Jeong, S.Y.; Mathenge, N.; Kassab, M.B.; Kolte, D.; Michos, E.D.; Albaghdadi, M. Sex disparities in the presentation, management and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndrome: insights from the ACS QUIK trial. Open Hear. 2021, 8, e001470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiyama, S.; Watanabe, T.; Arimoto, T.; Takahashi, H.; Shishido, T.; Miyashita, T.; Miyamoto, T.; Nitobe, J.; Shibata, Y.; Konta, T.; et al. Trends in Coronary Risk Factors Among Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction Over the Last Decade: The Yamagata AMI Registry. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2010, 17, 989–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boden, W.E.; O’rourke, R.A.; Teo, K.K.; Hartigan, P.M.; Maron, D.J.; Kostuk, W.; Knudtson, M.; Dada, M.; Casperson, P.; Harris, C.L.; et al. The Evolving Pattern of Symptomatic Coronary Artery Disease in the United States and Canada: Baseline Characteristics of the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive DruG Evaluation (COURAGE) Trial. Am. J. Cardiol. 2007, 99, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, R.; Begum, S.; Afridi, M.N. ACUTE MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION; FREQUENCY OF MODIFIABLE RISK FACTORS. Prof. Med J. 2016, 23, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, W. Yeh, Stephen Sidney, Malini Chandra, Michael Sorel, Joseph V. Selby, and Alan S. Go. Population Trends in the Incidence and Outcomes of Acute Myocardial Infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 2155–2165. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, W.J.; Frederick, P.D.; Stoehr, E.; Canto, J.G.; Ornato, J.P.; Gibson, C.M.; Pollack, C.V.; Gore, J.M.; Chandra-Strobos, N.; Peterson, E.D.; et al. Trends in presenting characteristics and hospital mortality among patients with ST elevation and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction from 1990 to 2006. Am. Hear. J. 2008, 156, 1026–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shyu, K.-G. Improvement of Outcomes in Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) by Getting with the Guidelines: From Taiwan ACS-full Spectrum Registry to Taiwan ACS-DM Registry. J Taiwan Cardiovasc Interv 2019, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, M.J.; Rueda, F.; Labata, C.; Oliveras, T.; Montero, S.; Ferrer, M.; El Ouaddi, N.; Serra, J.; Lupón, J.; Bayés-Genís, A.; et al. Non-STEMI vs. STEMI Cardiogenic Shock: Clinical Profile and Long-Term Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirchberger, I.; Meisinger, C.; Heier, M.; Kling, B.; Wende, R.; Greschik, C.; von Scheidt, W.; Kuch, B. Patient-reported symptoms in acute myocardial infarction: differences related to ST-segment elevation. J. Intern. Med. 2011, 270, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.J.; Rueda, F.; Labata, C.; Oliveras, T.; Montero, S.; Ferrer, M.; El Ouaddi, N.; Serra, J.; Lupón, J.; Bayés-Genís, A.; et al. Non-STEMI vs. STEMI Cardiogenic Shock: Clinical Profile and Long-Term Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeji, Y.; Shiomi, H.; Morimoto, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Matsumura-Nakano, Y.; Nagao, K.; Taniguchi, R.; Yamaji, K.; Tada, T.; Kato, E.T.; et al. Differences in mortality and causes of death between STEMI and NSTEMI in the early and late phases after acute myocardial infarction. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0259268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbadawi, A.; Elgendy, I.Y.; Mahmoud, K.; Barakat, A.F.; Mentias, A.; Mohamed, A.H.; Ogunbayo, G.O.; Megaly, M.; Saad, M.; Omer, M.A.; et al. Temporal Trends and Outcomes of Mechanical Complications in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. JACC: Cardiovasc. Interv. 2019, 12, 1825–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, S.M.; Borgerding, J.A.; Wood, G.B.; Maynard, C.; Fihn, S.D. Incidence, Risk Factors, and Outcomes Associated with In-Hospital Acute Myocardial Infarction. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e187348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicoll, R.; Wiklund, U.; Zhao, Y.; Diederichsen, A.; Mickley, H.; Ovrehus, K.; Zamorano, J.; Gueret, P.; Schmermund, A.; Maffei, E.; et al. Gender and age effects on risk factor-based prediction of coronary artery calcium in symptomatic patients: A Euro-CCAD study. Atherosclerosis 2016, 252, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | All included patients | Patients with NSTEMI | Patients with STEMI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 7353) | (n = 2987) | (n =4366) | ||

| Age (years) Female (%) |

63 ± 12 28.7 |

63 ± 11 31.7 |

64 ± 12 26.6 |

0.077 ˂0.001 |

| Smoking (%) Diabetes (%) |

51.7 35.3 |

48.3 37.8 |

54 33.6 |

˂0.001 ˂0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia (%) | 40.1 | 39.4 | 40.1 | 0.099 |

| Arterial hypertension (%) Family history for CAD (%) |

65.6 38.1 |

69.6 39.9 |

63 36.9 |

<0.001 0.009 |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 4.4 | 3.9 | 5.0 | 0.036 |

| Left bundle branch block (%) | 3.7 | 2.6 | 5.3 | <0.001 |

| Cardiogenic shock (%) | 3.7 | 2.1 | 4.9 | <0.001 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 9.5 ± 5.5 | 9.2 ± 5 | 9.8 ± 6 | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.8 ± 1.6 | 4.8 ± 1.6 | 4.5 ± 1.5 | 0.939 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.9 ± 1.3 | 2.0 ± 1.3 | 1.88 ± 1.2 | 0.001 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) Urea |

118 ± 74 9.2 ± 6 |

118 ± 74 9.2 ± 6 |

117 ± 73 9.1 ± 6 |

0.632 0.652 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 13.7 ± 3.2 | 13.7 ± 3.4 | 13.7 ± 3 | 0.942 |

| Heart rate at admission (beats/min) | 82.6 ± 23 | 82.5 ± 26 | 82.6 ± 20 | 0.822 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 50.6 ± 9 | 51.6 ± 9 | 49.8 ± 9 | <0.001 |

| Variable | All included patients | Patients with NSTEMI | Patients with STEMI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 7353) | (n = 2987) | (n =4366) | ||

| Coronary angiography (%) | 67.3 | 66.8 | 67.8 | 0.396 |

| Primary Percutaneous Intervention (%) | 50.1 | 43.6 | 55.2 | <0.001 |

| STEMI patients | NSTEMI patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | (CI 95%) | P value | OR | (CI 95%) | P value |

| Age Female gender Smoking Diabetes Arterial hypertension |

0.998 0.875 1.148 0.911 0.791 |

(0.994 - 1.002) (0.783 – 0.976) (1.037 - 1.271) (0.824 - 1.007) (0.714 - 0.878) |

0.412 0.017 0.008 0.069 <0.001 |

1.003 1.103 0.891 1.113 1.265 |

(0.999 - 1.008) (0.986 – 1.233) (0.804 - 0.988) (1.005 - 1.232) (1.139 - 1.405) |

0.151 0.086 0.028 0.039 <0.001 |

| Variable | Kosovo | Finland | Kosovo | Greece | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 7353) | (n = 1813) | P value | (n = 7353) | (n =1185) | P value | |

| Age (years) Female (%) |

63 ± 12 28.7 |

71 ± 13 34.6 |

<0.000 <0.001 | 63 ± 12 28.7 |

67 ± 13 26.2 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

| Smoking (%) Diabetes (%) |

51.7 35.3 |

20.4 24.8 |

<0.001 <0.001 | 51.7 35.3 |

41.4 27.6 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

| Arterial hypertension (%) STEMI (%) |

65.6 59.4 |

53.4 34.7 |

<0.001 <0.001 | 65.6 59.4 |

52.6 35.3 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

| NSTEMI (%) | 40.6 | 65.3 | <0.001 | 40.6 | 64.7 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).