1. Introduction

The recent advancement of artificial nucleotides, as well as their applications, have enabled the development of nucleic acid drugs, such as antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) and small interfering ribonucleic acids (siRNAs). Combined with emerging drug delivery system (DDS) technologies, therapeutic oligonucleotides are recently attracting increasing attention as new drug modalities. We recently summarized the physicochemical properties of these artificial modifications (ASOs and siRNAs) [

1] and DDS technologies based on material symbiosis [

2]. Messenger RNAs (mRNAs) are the target genes of these ASOs and siRNAs, and decreasing the number of disease-associated mRNAs can result in symptom relief, improved function, and prolonged survival for patients. However, even if a target mRNA expression is transiently decreased by ASOs or siRNAs, mRNAs would still be transcribed continually from genomic DNAs. Therefore, long-term administration is necessary, as a radical cure is unlikely. Theoretically, the direct suppression or modification of the target genes in chromosomal DNAs is more efficient and promising, and such a strategy can bring a paradigm shift in drug development. Sequence-recognition ability is key to targeting specific DNA regions. Thus, several genome-targeting tools have been developed to modify genome sequences or inhibit gene expression. For example, the growing literature on genome editing using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-associated protein 9 (CRISPR-Cas9) [

3] has promoted the feasibility of applying gene-editing technology to therapeutics [

4,

5]. However, these technologies require exogenous enzymes, and this could cause several drawbacks, such as cost, handling, and the induction of immune responses [

6]. Thus, the development of more symbiotic and facile methods is desirable. As previously mentioned, triplex-forming oligonucleotides (TFOs) and peptide nucleic acids (PNAs) exhibit significant potential as genome-targeting tools [

7,

8], considering that those aforementioned symbiotic ASO and DDS modification methods [

1,

2] are also applicable to TFOs and PNAs. Thus, this study is aimed at comprehensively reviewing the TFO and PNA technologies, focusing on the crucial findings and recent advancements, as well as their therapeutic application and future perspective.

2. Triplex-forming oligonucleotides

2.1. Outline of the triplex-forming oligonucleotide technology

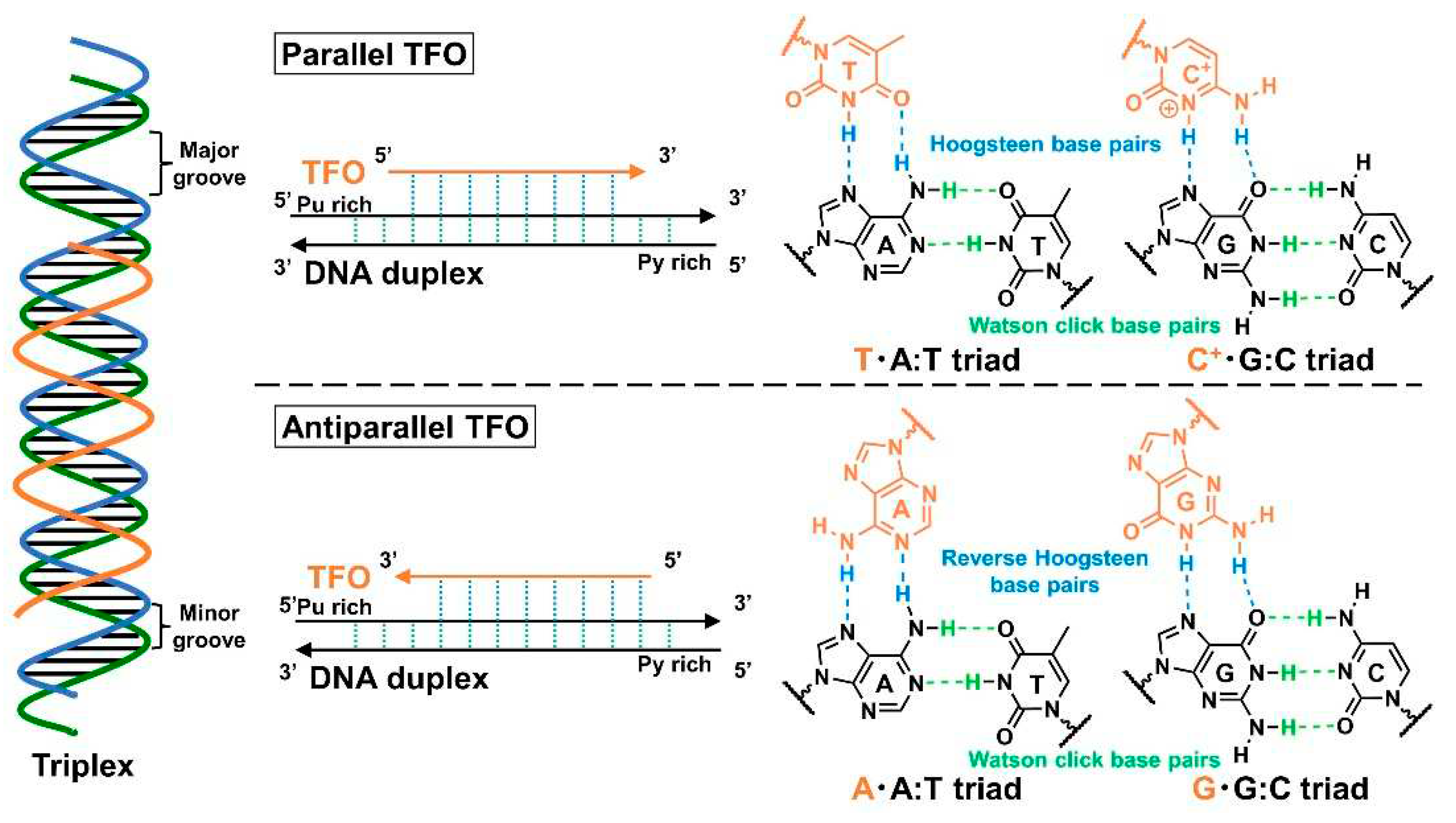

TFOs exhibit a short oligonucleotide sequence, which binds to their target DNA duplex by forming a triple-helix structure on the major groove of the DNA via the Hoogsteen (parallel triplex;

Figure 1a, up) or reverse Hoogsteen (antiparallel triplex;

Figure 1a, down) hydrogen bonds. In the parallel triplex, thymine (T) recognizes the adenine (A):T base pairs to form a T·A:T triad, and protonated cytosine, C (C

+), recognizes the guanine (G)·C base pairs to form a C

+·G:C triad. Additionally, A recognizes the A:T base pairs to form an A·A:T triad, and G recognizes the G:C base pairs to form a G·G:C triad in the antiparallel triplex. The extant studies on the human genome revealed that most annotated protein-coding genes in the human genome contain a minimum of one unique targeting site for TFOs (triplex target sites, TTS) in the promoter or transcribed regions [

9,

10]; they also contain several TTS-mapping tools to facilitate the selection of target sequences for TFOs [

11,

12,

13].

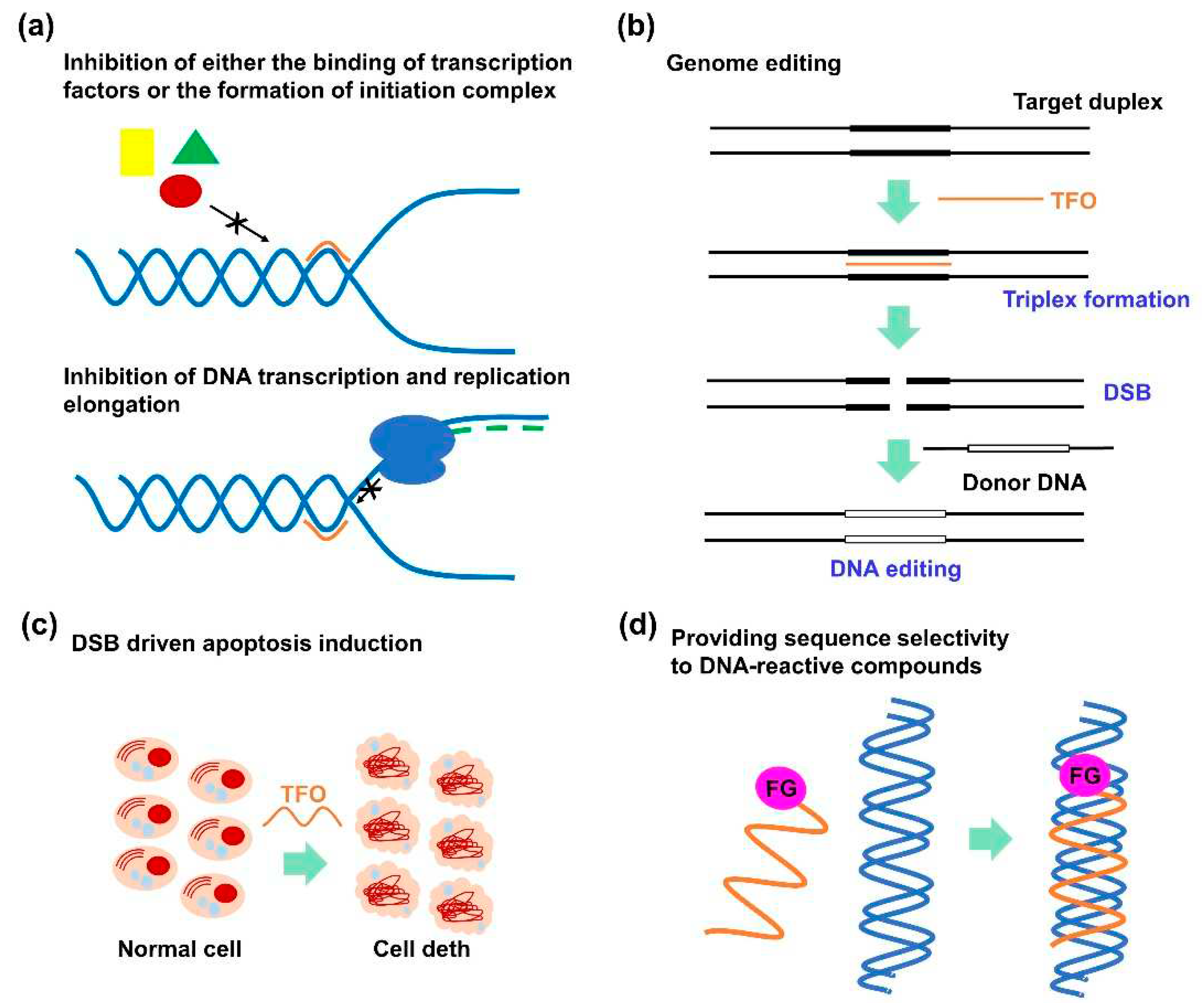

Various TFO-treatment mechanisms have been reported. First, TFOs were developed for antigene strategies targeting clinically essential genes, particularly oncogenes, such as c-myc, bcl-2, HER2, and Ets-2 [

14]. TFOs can downregulate gene expression levels by inhibiting either the binding of transcription factors to promoter regions [

15], forming the initiation complex (

Figure 1b) [

16], or the transcriptional elongation (

Figure 2a) [

17]. Second, TFOs can be employed to induce DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) [

18], which can be explored for genome editing (

Figure 2b) [

19] or apoptosis induction (

Figure 2c) [

20,

21]. Tiwari et al. investigated the DNA DSB mechanism, confirming that triplex formation perturbed DNA replication fork progression, which resulted in a fork collapse and provoked DNA DSBs [

22]. Third, by tethering functional molecules to a TFO, these functional molecules can exhibit sequence-specific reactivity to the target DNA (

Figure 2d). Particularly, the introduction of a crosslinking agent into TFO has been widely investigated considering that the crosslinking between TFO and the target DNA enables irreversible triplex formation that can enhance the antigene activity of TFO [

23]. Crosslinking-driven DNA damage can also induce several DNA-repair events that can be exploited for genome-editing technology [

24].

2.2. Advancements in the engineering of triplex-forming oligonucleotides

2.2.1. Triplex-stabilization technology

As aforementioned in

Section 2.1., stable triplex formation requires consecutive polypurine sequences in the target dsDNA as the Hoogsteen hydrogen bonds can only be formed between the TFO and purine bases of the target dsDNAs. The pyrimidine bases in the polypurine strand of the target DNA duplexes cause significant losses in the thermodynamic stability of the triplex. Moreover, the required protonation of cytosine in the parallel motif (

Figure 1) limits the

in vivo application of triplexes. There are ongoing efforts to solve these intrinsic triplex-stability issues that restrict the target sequences. One such approach for overcoming these issues involves developing artificial nucleobases that can form several hydrogen bonds with the pyrimidine-base-interrupting site of the target DNA duplex [

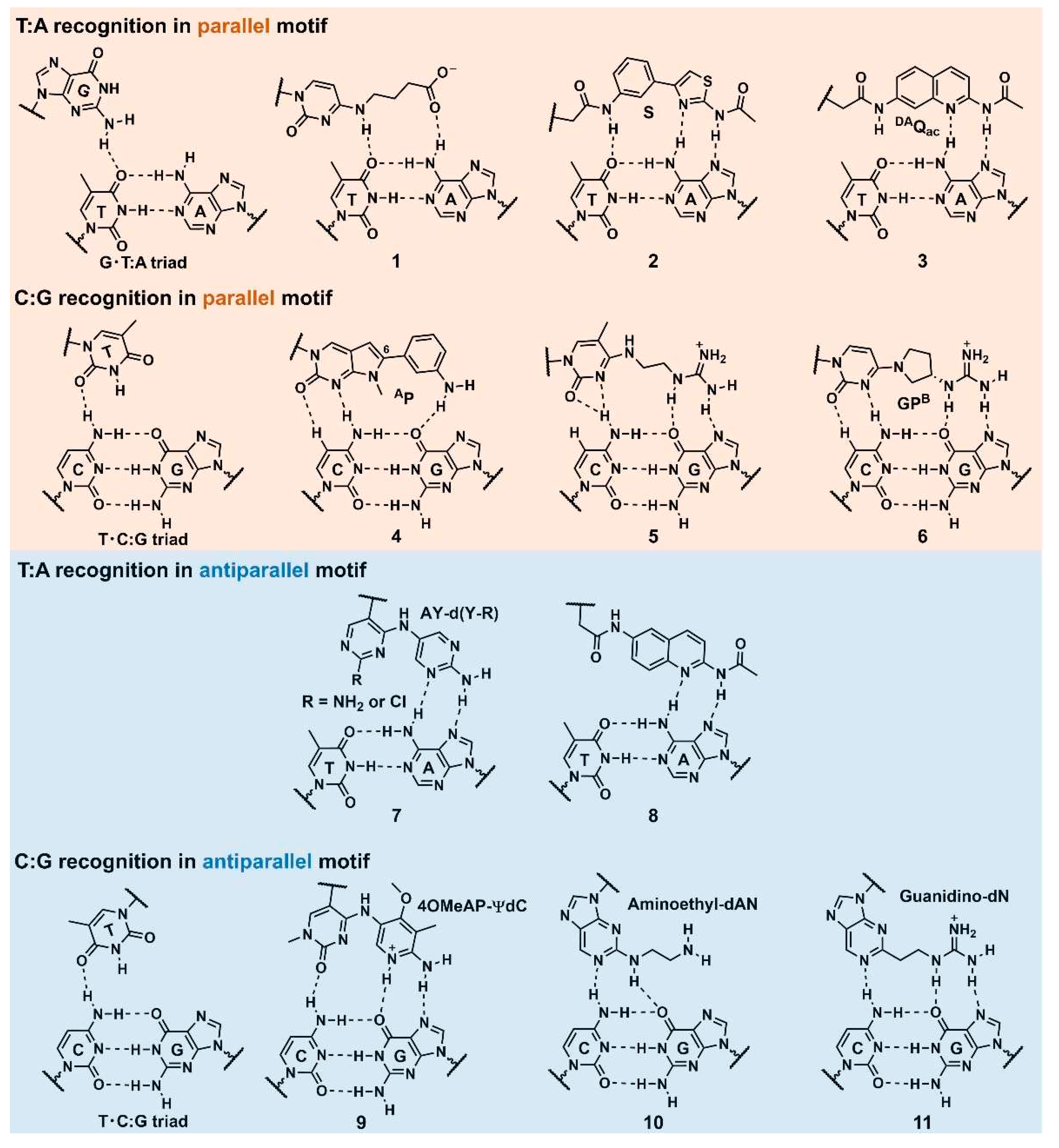

25]. Although the natural nucleobases, G, can form a G·T:A triad in a parallel motif [

26], and another natural nucleobase, T, can form a T·C:G triad in parallel and antiparallel motifs [

27], only one hydrogen bond exists in these interactions; the bond is not sufficient for stable triplex formation (

Figure 3). In this section, we considered several examples of the aforementioned artificial nucleobases, as well as other approaches utilizing DNA-intercalating molecules, and introduced base stacking interaction, focusing on essential findings, and recent advancements. The conventionally applied modifications for other oligonucleotide drugs, such as ASOs, and siRNAs, were not particularly considered in this review.

2.2.1.1. Artificial nucleobases recognizing pyrimidine base interruption in the target double-stranded DNA

2.2.1.1.1. Recognition of the thymine–adenine base pair in a parallel motif

Miller’s group reported an

N4-(3-carboxypropyl)deoxycytosine nucleobase (

Figure 3,

1) for targeting a TA base pair in a parallel motif. They predicted that its constituent carboxylic acid can interact with the 6-amino group in A of the T:A base pair. The ultraviolet (UV)-melting experiments of 15-mer TFO containing

1 selectively recognized a T:A base pair in dsDNA. The melting temperature (

Tm) of this TFO (Tris buffer, pH 7.0) was 7°C higher than that of the triplex comprising the G·T:A triad [

28]. Sun’s group developed an artificial nucleobase,

S, containing two unfused aromatic rings and an acetamide moiety that was attached to 2′-deoxyribose (

Figure 3,

2). The S·T:A triad was significantly more stable than the G·T:A triad. The group proposed that the aminothiazole part of

S was key to T:A recognition, forming three hydrogen bonds between the T:A base pair in its proposed recognition scheme [

29]. Recently, Ohkubo’s group reported a new artificial nucleobase exhibiting a quinoline skeleton,

DAQac (

Figure 3,

3). The UV-melting experiments of the triplex consisting of the 18-mer TFO containing

DAQac and a hairpin dsDNA revealed that this nucleobase recognized the T:A and C:G base pairs with

Tm values (pH 7.4) that were 13°C higher than those of the A:T and G:C base pairs, respectively [

30].

2.2.1.1.2. Recognition of the guanine–cytosine base pair in a parallel motif

Brown’s group reported several artificial nucleobases exhibiting

N-methylpyrrolo[2,3-

d]pyrimidine-2(7

H)-one as their core structures. They derivatized the 6-position of this core skeleton to introduce additional functionality. They noted that the nucleobase,

AP (

Figure 3,

4), was the optimum analog for the C:G recognition [

31]. Seidman’s group developed one of the most suitable nucleobases for C:G recognition to target the chromosomal Hprt gene sequence with a single C:G interruption. Combined with 2’-

O-methyl modification,

N4-(2-guanidinylethyl)-5-methylcytosine nucleobase (

Figure 3,

5) emerged as the best in terms of affinity and selectivity to the C:G base pair. The thermal stability of the triplex was 15°C higher than that of the T·C:G-triad-containing canonical triplex. This research demonstrated that the guanidine unit is a promising counterpart of G in the C:G base pair [

24]. Further, Obika’s group developed an artificial nucleobase,

GPB (

Figure 3,

6) [

32], containing a guanidine unit as a counterpart of G in combination with a locked NA (LNA) that is a nucleotide analog bearing a 2'-

O,4'-

C-methylene linkage. The partial introduction of LNA into TFO can stabilize the triplex by inducing a preorganized helical structure for triplex formation [

33]. The sequence selectivity of the

GPB-containing 15mer triplex was high, and its thermal stability was 15°C higher than that observed using a T·C:G triad.

2.2.1.1.3 Recognition of the thymine–adenine base pair in an antiparallel motif

In 2020, Taniguchi, and Sasaki’s group developed a C-nucleoside analog,

AY-d(Y-R), bearing a pyrimidine skeleton (

dY) and an amino-pyrimidine unit (

AY) for the recognition of a T:A base pair (

Figure 3,

7). However, the association constants (

Ka) of the triplex formation depended on the neighboring bases, and the adjacent dG base at the 5’ side of the target T appeared to be required for stable triplex formation [

34]. Recently, Ohkubo’s group reported an artificial nucleobase, 2-acetamido-6-aminoquinoline (

6DAQac) for T:A-selective recognition (

Figure 3,

8). Generally, G-containing antiparallel TFOs were self-assembled, forming other higher-order structures, such as G-quartet, at high salt concentrations. Therefore, their binding ability to the target dsDNA was significantly reduced. However,

6DAQac formed a triplex structure at low and high salt concentrations, representing valuable features for biological applications [

35].

2.2.1.1.4. Recognition of the cytosine–guanine base pair in the antiparallel motif

Recently, Taniguchi’s group reported several artificial nucleobases for detecting C:G-interrupting sequences [

36,

37,

38,

39]. They designed 2-amino-4-methoxypyridinyl pseudo-dC (

4OMeAP-ѰdC) with a high p

Ka value (p

Ka = 7.5) of the 1-

N position (

Figure 3,

9). This nucleobase exhibited high affinity and selectivity to the C:G base pair, independent of the adjacent base pairs. The TFOs bearing this nucleobase formed a stable triplex with the hTERT and Cyclin D1 gene sequences containing multiple (3–4) C:G-inversion sites [

36].

Aminoethyl-dAN is another artificial nucleobase possessing an amino-nebraline (AN) skeleton (

Figure 3,

10); it detected

5mC:G and C:G. Triplex stability depends on the adjacent bases, although the affinity to

5mC:G was higher than to C:G, demonstrating better

5mC:G recognition over C:G recognition [

38]. A novel artificial nucleobase, 2-guanidinoethyl-2’-deoxynebularine (

guanidino-dN) was developed based on

10 (

Figure 3,

11). The nucleobase (

11) exhibited high binding affinities to

5mC:G and C:G base pairs in all four combinations of the adjacent bases. They demonstrated the utilities of the TFOs containing this nucleobase by inhibiting the activity of the ten–eleven translocation enzyme, which oxidizes the

5mC:G base pair in dsDNA [

39].

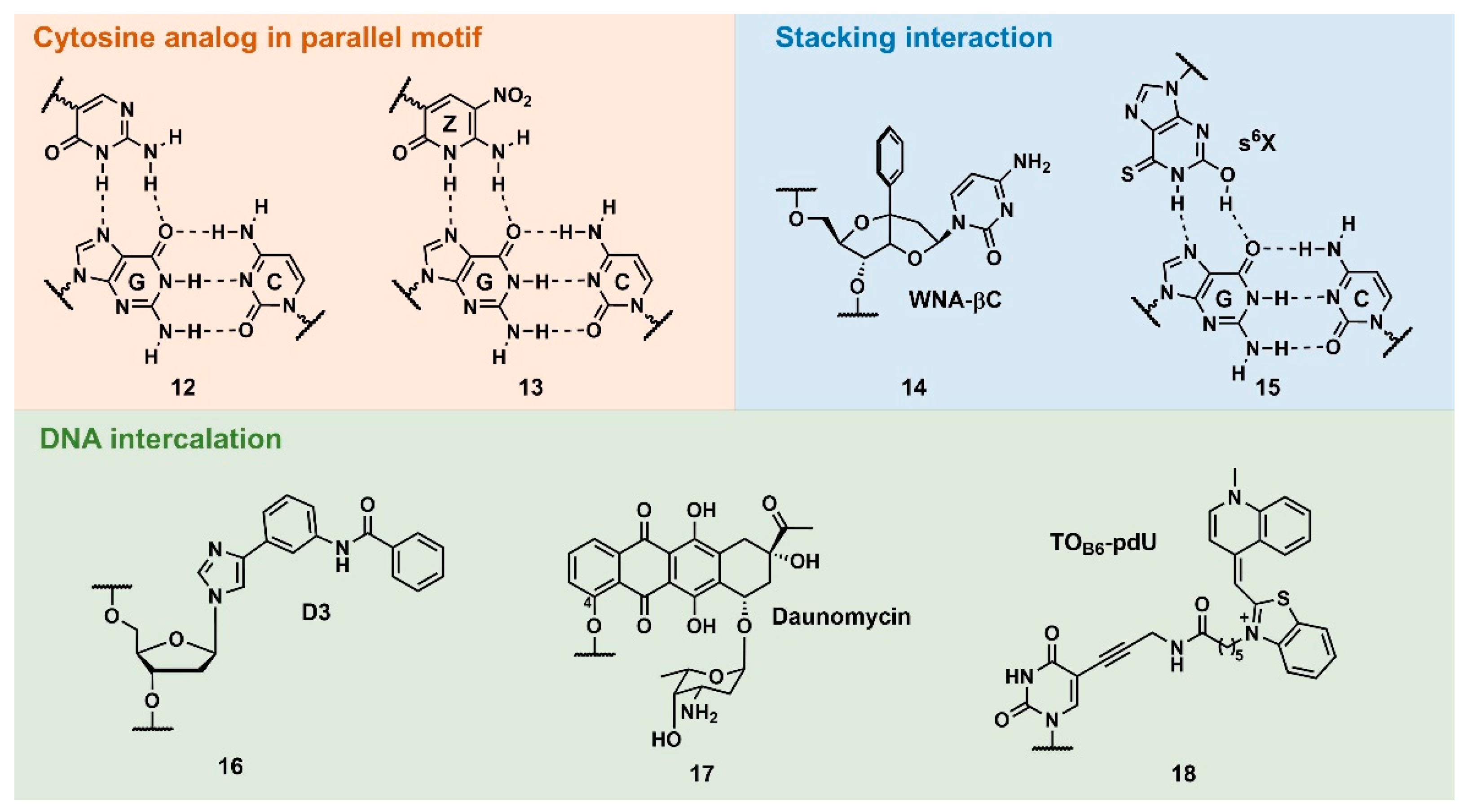

2.2.1.2 Other triplex-stabilization techniques using artificial nucleobases

2.2.1.2.1 Cytosine mimic that can form hydrogen bonds with the guanine–cytosine base pair in a parallel motif

The natural parallel TFO requires low-pH conditions (pH < 6.0) owing to the low p

Ka value of the

N3 position of C (p

Ka = ~4.5) (

Figure 1,

C+·G:C triad) [

40]. Several C analogs were developed with higher basicity than a C (5-methylcytosine, 5-mC) or with proper hydrogen-bonding groups (pseudoisocytosin;

Figure 4,

12) [

40]. Among them, 6-amino-5-nitropyridine-2-one (

Z) seemed to be the most practical for this purpose, as the thermodynamic stability of the triplex was unusually higher than that of the underlying duplex (

Figure 4,

13) [

41].

Z is an uncharged C-glycoside mimic of C

+ bearing a nitro group at the 5-position. The p

Ka value of the

N3 position of

Z is ~7.8, and this facilitates stable triplex formation in isolated and contiguous G:C base-pair sequences even under basic conditions (pH 9.0), and enzymatic incorporation of

Z was also demonstrated. It was assumed that the nitro group contributed to this stability by decreasing the epimerization of 1’-anomeric carbon, as well as the stacking interactions.

2.2.1.2.2. Stacking interactions

Sasaki’s group developed several W-shaped nucleoside analogs (WNA) exhibiting a bicyclic skeleton, as well as an additional aromatic ring. This aromatic ring was incorporated to increase the stability of the triplex via the stacking interaction. For example,

WNA-βC (

Figure 4,

14) displayed the recognition ability of C:G-interrupting base pair with some sequence limitation [

42]. Ohkubo’s group also reported several artificial nucleobases containing a sulfur atom to increase base-stacking interactions. Further, 2’-deoxy-6-thioxanthosine (

s6X) was developed for G:C base-pair recognition (

Figure 4,

15). The consecutive incorporation of

s6X into TFO targeting G:C-rich sequences resulted in a 50-fold stable-triplex formation than using unmodified TFO owing to stacking interactions [

43].

2.2.1.2.3. DNA intercalation

In 1992, Dervan’s pioneering work demonstrated pyrimidine–purine recognition using an artificial DNA intercalator,

D3 (

Figure 4,

16).

D3 was originally designed to recognize the CG base pair via two hydrogen bonds. However, employing proton NMR studies, it was revealed that this recognition was the result of the DNA intercalation of

D3 at the 3’-site of the target base pair [

44]. A natural compound, such as daunomycin, was also explored for the stabilization of the triplex structure. Catapano’s group introduced daunomycin at the 5’-end of GT-rich antiparallel TFO via a hexyl linker that was attached to the C-4 position of daunomycin (

Figure 4,

17). The daunomycin-conjugated TFO increased the stability of the triplex without compromising its specificity and reduced the transcription of the endogenous c-myc gene in cells [

45]. Recently, Brown’s group reported the stabilization of triplex by thiazole orange (TO)-intercalator-introduced T-derivatives,

TOB6-pdU (

Figure 4,

18). TFO containing three

TOB6-pdU increased the thermodynamic stability of the triplex at pH 7 by 45°C compared with unmodified TFO. Moreover, employing 5-(1-propynyl)cytosine as a counterpart of the C:G-inversion site,

TOB6-pdU-modified TFO can form a stable triplex with these pyrimidine base interrupted sequences [

46,

47].

2.2.2. Recent advancements in functional triplex-forming oligonucleotides for DNA targeting

By tethering functional molecules to TFO, such molecules can exhibit sequence-specific reactivities toward the target DNA (

Figure 2d). Particularly, the introduction of a crosslinking agent into TFO has been widely investigated, as the crosslinking between TFO and the target DNA enables irreversible triplex formation that can enhance the antigene activity of TFO. Thus, crosslinking-driven DNA damage can induce several DNA-repair events that can be explored for genome-editing technology. Therefore, crosslinkable TFOs exhibit great potential as therapeutic oligonucleotides. In addition to the crosslinking, certain metalloenzyme-tethered TFOs can directly cut DNA and are considered new genome-targeting tools. The recent advancements of these functionalized TFOs will be introduced in this section.

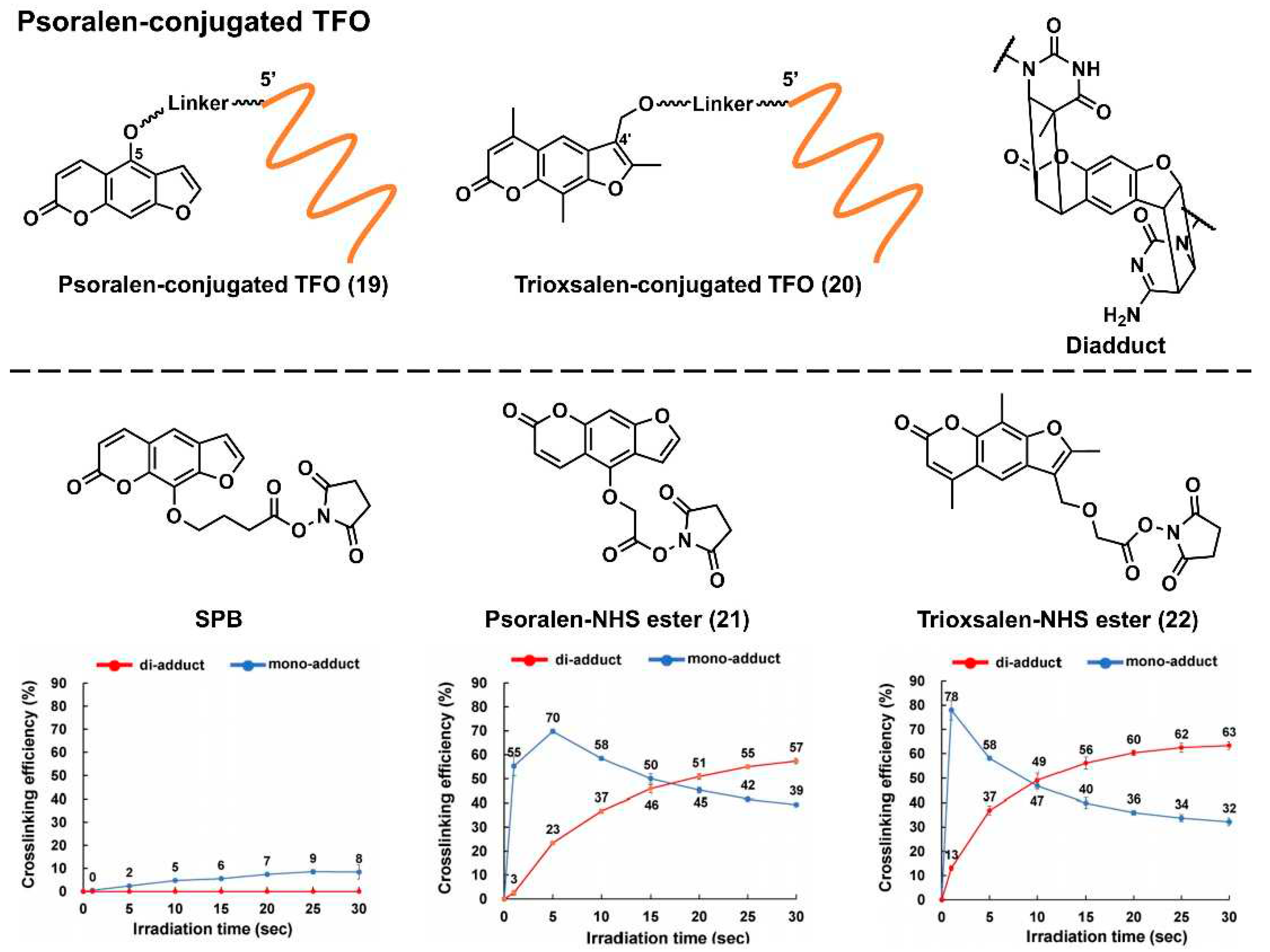

2.2.2.1. Targeted crosslinking using psoralen-conjugated triplex-forming oligonucleotide

Psoralen is a representative crosslinking molecule. It is a furocoumarin natural compound that is produced by various plants. It has been used to treat skin pigmentation disorders [

48]. Psoralen intercalates into the pyrimidine base junction of the DNA double helix. Under UV irradiation (365 nm), the furan-ring (the 4’ and 5’ positions) and pyrone-ring (the 3 and 4 positions) sides of psoralen can undergo a [2 + 2] photocyclization reaction between the 5 and 6 positions of the pyrimidine base to form a cyclobutene ring [

49]. Generally, the first [2 + 2] photocyclization proceeds at the furan-ring side to obtain a diadduct product (

Figure 5), as the pyrone-ring moiety of psoralen is necessary for photoactivation. The furan side of psoralen may form an electron donor–acceptor (EDA) complex with a pyrimidine base.

This EDA complex facilitates the first [2 + 2] photocyclization of the furan ring; therefore, diadduct formation is relatively unique to DNA. Several researchers have introduced psoralens into TFOs to perturb or induce DNA transcription or mutation, respectively. The chemical structures of the representative Ps–TFOs are shown in

Figure 5. For the first time, Hélène’s group introduced psoralen into the 5’-end of TFO in which the linker was attached to the 5-positions of psoralen via a C6 linker (

Figure 5,

19). Subsequently, they demonstrated the

in vitro sequence-specific transcription inhibition by the formation of a covalent bond at a promoter sequence [

50]. Conversely, Glazer’s group demonstrated the first targeted mutagenesis of the λ-phage genome in bacteria using trioxsalen-conjugated TFO,

20, in which 4’-hydroxymethyl-4,5’,8-trimethylpsoralen was attached to the 5’-end of TFO via a two-carbon (C2) linker arm [

51]. They also investigated the effect of the length of the linker of Ps–TFO on the mutation frequencies at the targeted site, demonstrating that the C6 linker outperformed the C4 one (14% and 3%, respectively) [

52]. Seidman’s group demonstrated several endogenous genome editing of mammalian cells, such as gene knock-in [

53] and sequence conversion [

54], via the homology-directed repair pathway by the coinjection of the single-stranded DNA donor with

20 [

53,

54]. Our group applied

20 to the detection of 5-mC, which is an essential epigenetic marker related to cell differentiation and cancer development. Employing

20 in combination with an artificial nucleic acid chaperone (PAA-g-Dex: poly(allylamine)-graft-dextran),

20 was selectively crosslinked to dsDNA containing 5-mC [

55].

The psoralen unit of these Ps–TFOs was generally introduced by the phosphoramidite method, which requires an automated DNA synthesizer and strict anhydrous conditions and is relatively not easy to operate. Succinimidyl-[4-(psoralen-8-yloxy)]-butyrate (

Figure 5,

SPB; ThermoFisher Scientific, MA, USA) is commercially available. It facilitates the convenient introduction of a psoralen moiety into TFO. However, we demonstrated that the linker position (8-position of psoralen) was not appropriate for crosslinking. Therefore, we developed two novel psoralen NHS esters (

Figure 5,

21 and

22) [

56]. We demonstrated the facile preparation of these Ps–TFOs by the conjugation of a 5’-amino-linker-tethered TFO with

21 and

22, observing efficient crosslinking formation (diadduct formations were 0%, 57%, and 63% for SPB,

21, and

22 after UV irradiation for 30 s, respectively). This NHS ester can be used for other TFO analogs, such as PNA (discussed in section 3), which recently exhibited considerable potential as a genome-targeting tool [

56,

57].

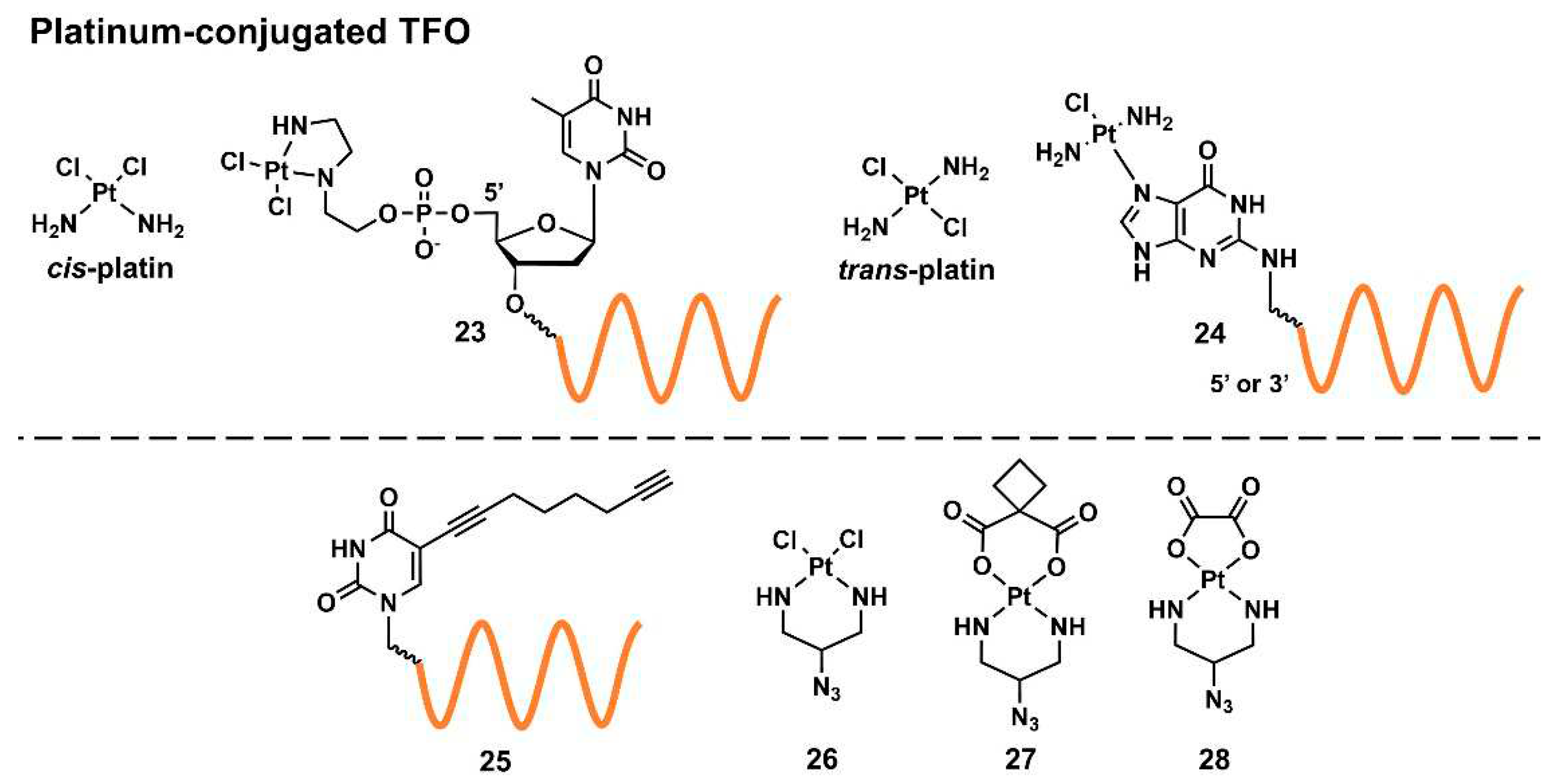

2.2.2.2. Targeted crosslinking using platinum-conjugated triplex-forming oligonucleotides

Platinum compounds display DNA crosslinking abilities. A cancer chemotherapeutic drug,

cis-platin, is a representative drug of this class (

Figure 6). Platinum compounds primarily react with

N-7 of purine bases, particularly G, to form a highly stable coordination complex resulting in intrastrand and interstrand crosslinking in DNAs [

58].

The structures of the reviewed platinum-compound-conjugated TFOs (Pt–TFOs) are summarized in

Figure 6. In 2002, McLaughlin’s group reported TFO tethered with a

cis-bifunctional platinated complex at the 5’ end of its T constituent (

23) [

59]. As the solid-phase-synthesis-based incorporation of the platinum complex in an oligonucleotide yielded an inactivated species, Pt–TFO was synthesized by a two-step procedure: (1) the phosphoramidite-method-based incorporation of a 2-(2-aminoethylamino)ethanol chelator and (2) metal complexation after the removal from the solid support. They revealed the sequence-specific delivery of the platinum complex to the target genes and the selective crosslinking using Pt–TFO. Conversely,

trans-platin-type conjugates (

Figure 6) have been explored for this purpose. Miller’s group reported that the incorporation of

N-7-platinated G-nucleosides (

24) to the 3’- and 5’-ends of TFO enabled TFOs to form highly stable adducts, resulting in interstrand crosslinking; the 2’-

O-methyl analogs of these TFOs inhibited the transcription and replication of plasmid DNAs in cells [

60]. Furthermore, they decreased the mRNA and protein levels of the endogenous human androgen receptor gene by 40% and 30%, respectively [

61]. Recently, Kellett’s group reported a click-chemistry approach for functionalizing an alkyne-modified TFO (

25) [

62]. They developed several azido-bearing

cis-platinum(II) complexes (

26–

28) and reported the modular synthesis of Pt–TFOs. Combined with TO, the aforementioned DNA-intercalating and triplex-stabilizing fluorophore (

Figure 4,

18) enhanced target binding and discrimination between target and off-target sequences.

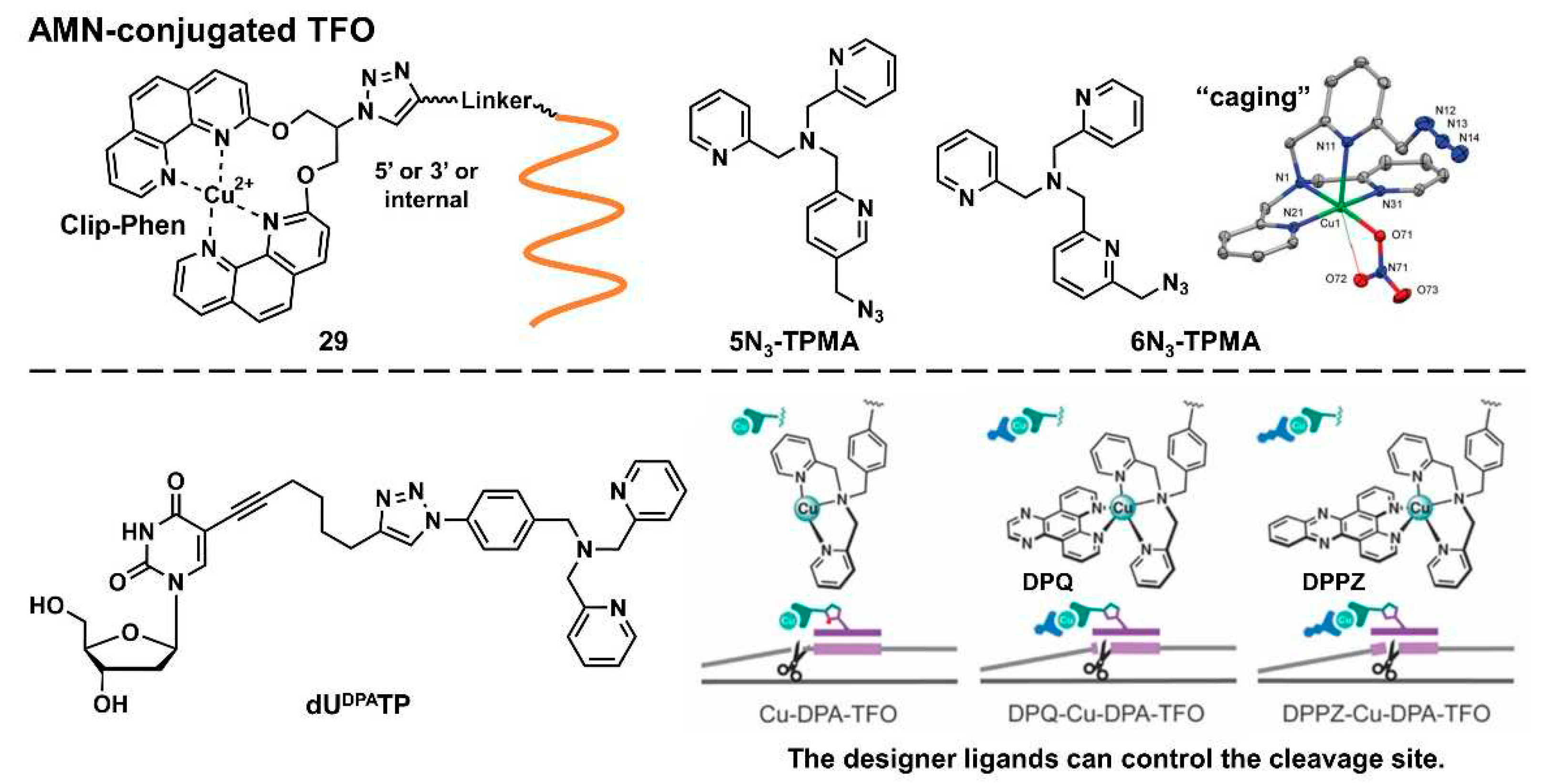

2.2.2.3. Artificial metallonuclease-conjugated triplex-forming oligonucleotides

Diverse metal complexes can cleave DNA. Combined with TFOs, such metal complexes acquire sequence selectivity and can become artificial nucleases and new genome-editing tools. As there is a comprehensive and excellent review on this topic [

63], we only introduced recent advancements in this field here. In 2020, Hocek’s group developed several hybrids of Cu-chelated clamped phenanthroline (Clip-Phen) artificial metallonuclease (AMN) with TFOs (

Figure 7,

29) by the click-chemistry approach and achieved sequence-specific dsDNA cleavage. A Clip-Phen cupric complex can induce dsDNA cleavage in the presence of molecular oxygen and an external reductant, such as a thiol, or ascorbate. These AMN-conjugated TFOs (AMN–TFOs), in which AMN was linked to the 5’-end or an internal T-base of TFO through a flexible linker, facilitated the significant cleavage of the target duplex DNA (up to 34%) [

64].

Kellett’s group also reported several AMN–TFOs [

65,

66,

67]. They developed new copper-binding scaffolds,

5N3-TPMA and

6N3-TPMA (TPMA = tris(2-picolyl)amine), that were designed as “caging” chelators to stabilize copper(II) ions (

Figure 7). These polypyridyl ligands were incorporated in TFO by a click reaction, after which the purine-rich tracts of the green fluorescent protein gene were efficiently targeted [

66]. They also demonstrated the enzymatic incorporation of DPA-modified uridine triphosphates (

dUDPATP) (

Figure 7) into TFO to develop AMN–TFOs that enabled the practical application of this AMM [

67]. Combined with designer intercalators (

Figure 7,

DPQ or

DPPZ) [

65], the cleavage site was controlled toward achieving high-precision DNA cleavage [

67].

2.3. Recent advancements in therapeutic applications of triplex-forming oligonucleotides

In 2011, Gillet’s group first demonstrated the effectiveness of methylphosphonate TFO in targeting tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). TNF-α is a proinflammatory cytokine that is crucial to the pathogenesis of many inflammatory diseases, such as arthritis. The anti-TNF-α TFO in a 0.9% NaCl aqueous solution was injected into acute- and chronic-arthritis model rats and significant decreases were observed in the disease development in both models. Further, anti-TNF-α TFO efficiently prevented synovitis, cartilage, and bone destruction in their joints. The TFO activity was significantly higher than that of the corresponding siRNA, indicating the criticality of direct gene targeting [

68].

The amplification and (or) overexpression of the c-myc gene were associated with the poor prognosis or decreased survival of cancer patients. Recently, Huo’s group reported efficient, and precise c-myc gene silencing using TFO. They demonstrated the controlled release of TFO using gold nanoparticle-conjugated TFO (Au–TOF NPs) and the mediation of the self-assembly of ultrasmall AuNPs by another single oligonucleotide that exhibits a complementary sequence to the tail part of TFO. Both oligonucleotides were assembled into large-size sunflower-like structures and disassembled under near-infrared (NIR) irradiation to release the "active" TFO. Tumor inhibition was studied using BALB/c nude mice. The tumor growth was synergistically controlled by the pre-incubation time and NIR-irradiation time point [

69].

Recently, the therapeutic potential of TFO against the HER2-gene-amplified breast cancer was demonstrated [

70,

71]. Rogers’s group reported the selective apoptosis induction of the HER2-amplified breast cancer cells. It was experimentally determined that multiple triplex formations in amplified genes caused significant DNA damage through DNA DSBs, resulting in cell apoptosis response [

71]. The selective anticancer activity was demonstrated using a mouse xenograft tumor model. This research indicated the effectiveness of targeting amplified gene loci using TFO.

3. Peptide nucleic acid

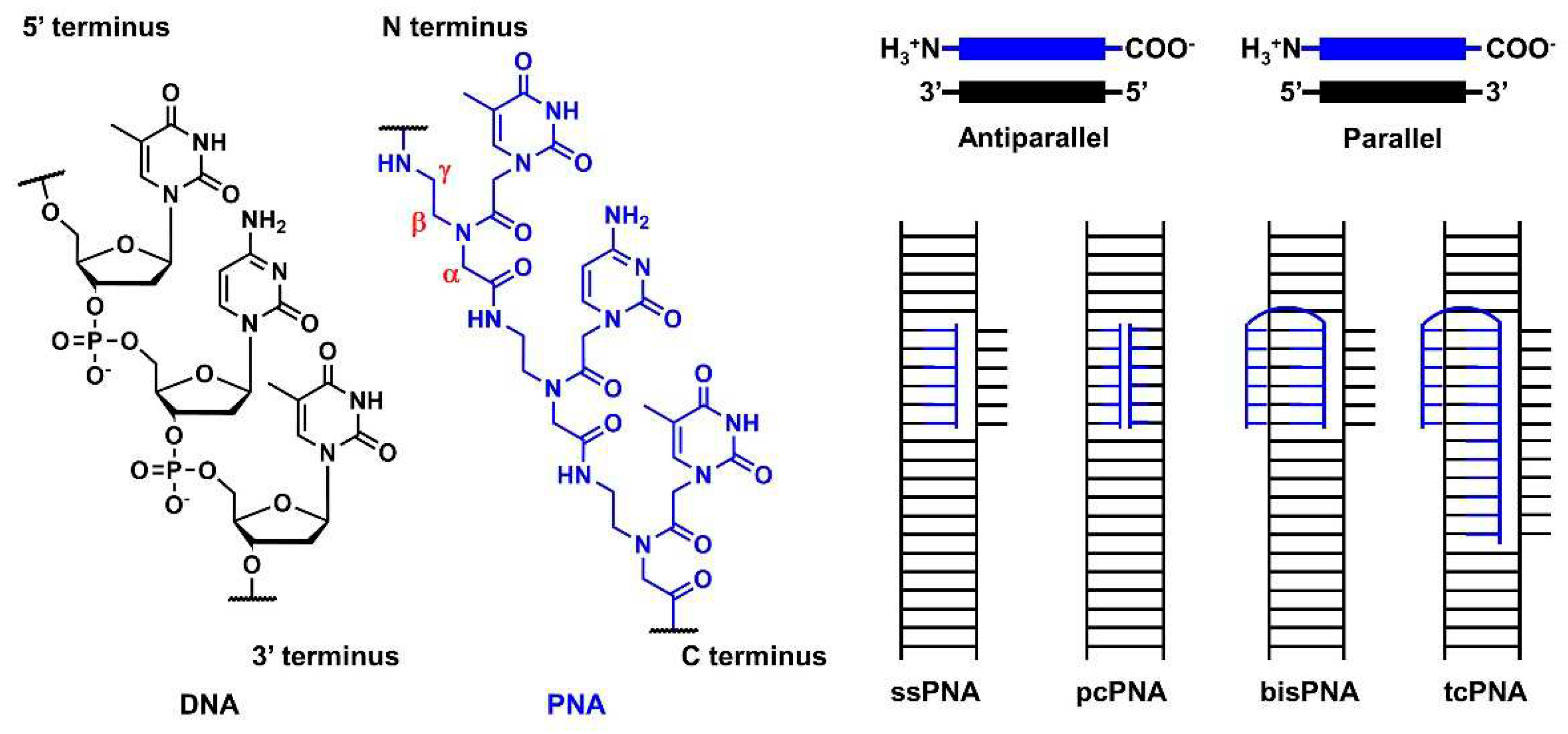

3.1. Outline of the peptide nucleic acid technology

PNA was first reported by Nielsen’s group in 1991 [

72,

73]. It comprises an electrically neutral aminoethyl glycine backbone. PNA is an artificial DNA analog in which the negatively charged phosphodiester backbone is replaced by a charge-neutral pseudopeptide backbone (

Figure 8). PNA exhibits several conformational flexibilities. It can adopt the A and B helical structures upon binding to target RNA and DNA, respectively, and form antiparallel, and parallel duplexes. The antiparallel duplex is generally more stable than the parallel one. The charge neutrality of PNA enabled the binding to the complementary DNA sequence target with increased affinity and sequence specificity, resulting in the unique mode of PNA actions as follows. Considering the high affinity of PNA to DNA, single-stranded PNA (ssPNA) can invade dsDNA (

Figure 8). Pseudocomplementary PNA (pcPNA) [

74] was designed to form two PNA/DNA duplexes. pcPNA contains artificial nucleobases, where 2,6-diaminopurine (D) and 2-thiouracil (sU) are used instead of A and T, respectively, to avoid PNA/PNA self-duplex formation by the steric hindrance between them (

Figure 10,

42). The bifunctional PNA [

75] and tail-clamp PNAs (tcPNAs) [

76] were designed to “clamp” one DNA strand comprising two sections that are connected by a flexible linker that enables the invasion of the target DNA duplex. The invasion is initiated by the triplex formation of one section through Hoogsteen base pairing, and the other section forms Watson–Crick base pairing with the same DNA strand, resulting in a PNA/DNA/PNA triplex. This “clamp” distorts the DNA structure, followed by the recruitment of endogenous repair factors that can be explored for genome editing. Further, tcPNA contains an extended Watson–Crick binding section to create a “tail” for distorting the target DNA for an extended stretch with increased affinity to DNA. The aforementioned PNA designs have their advantages, and their effectiveness has been demonstrated in antigene and genome editing.

3.2. Advancements in peptic nucleic acid engineering

The unique characteristics of PNA, the aforementioned charge neutrality, and structural flexibility, also cause several drawbacks, such as low water solubility, poor cellular uptake, self-aggregation, and orientational ambiguity, in target-sequence recognition. Many modifications have been explored to overcome these drawbacks to improve the application potential of PNAs. As many comprehensive and excellent reviews have described these modifications and applications [

73,

77,

78,

79,

80], we only introduced selected examples, focusing on essential findings, and recent advancements.

3.2.1. Modification of the peptic nucleic acid backbone

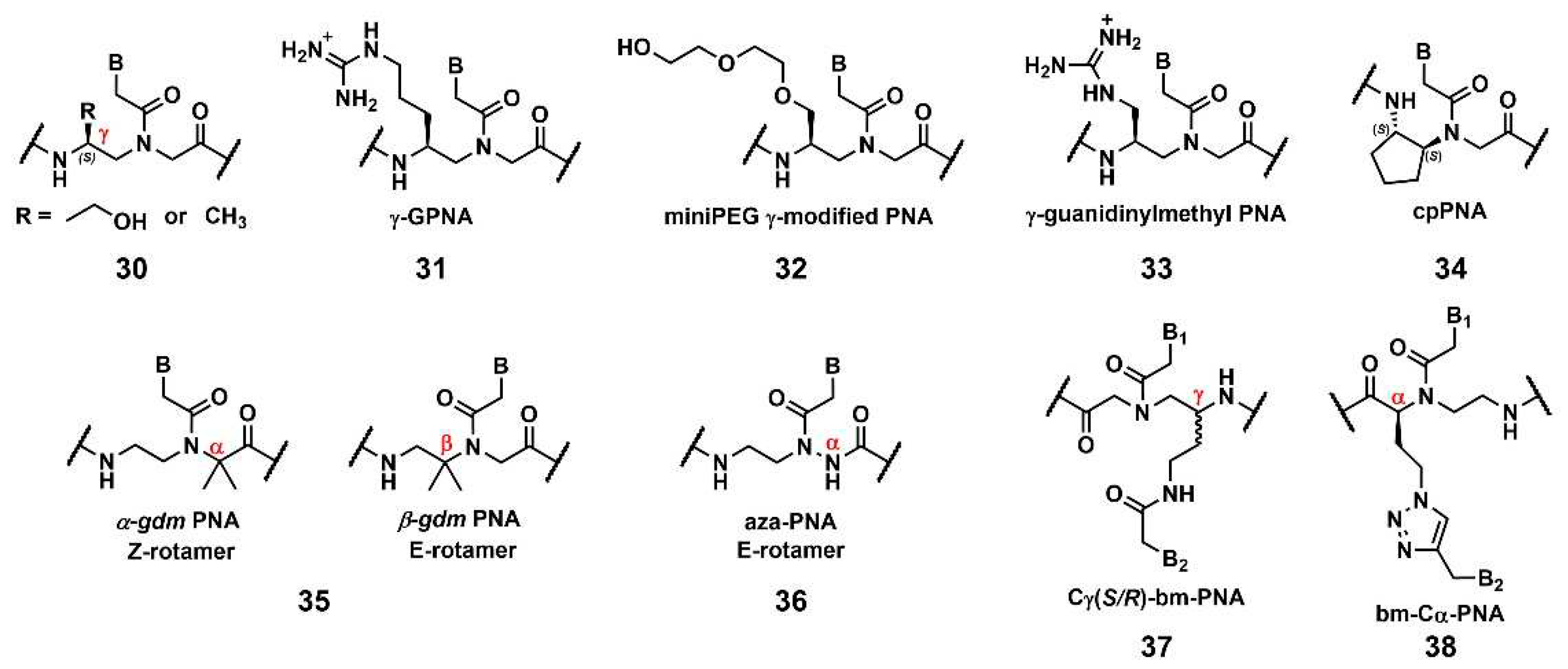

Ly’s group reported that the introduction of simple substituents, such as methyl, or hydroxymethyl, at the γ-position induced the preorganized, right-handed helical structure of the PNA backbone (

Figure 9,

30), resulting in strengthened binding to complementary DNA and RNA [

81]. The same group demonstrated that the modification of the γ-position of PNA with guanidine,

γ-GPNA (

Figure 9,

31), greatly improved the cellular uptake of

γ-GPNA [

82]. They also developed

miniPEG γ-modified PNA (

Figure 9,

32) exhibiting superior nucleic acid binding due to the better preorganization of its PNA backbone. The

miniPEG γ-modified PNA can invade any dsDNA sequence by only the Watson–Crick base pairing to recognize the target [

83]. Tahtinen’s group developed

γ-guanidinylmethyl PNA (

Figure 9,

33) for recognizing triplex-forming PNAs. Three consecutive incorporations of

33 in PNA achieved the best binding affinity and the Hoogsteen-face selectivity of the oligomer with improved cellular uptake [

84]. Presently, the aforementioned

γ-GPNA and

miniPEG γ-modified PNA are widely used PNA derivatives for therapeutic purposes.

Appella’s group reported the detailed biophysical and structural properties of

S,

S-cyclopentyl PNA, cpPNA (

Figure 9,

34) [

85,

86]. The cyclopentane ring restricts the conformational flexibility of the PNA backbone, thus inducing a right-handed helix that favors binding to complementary DNA. Further, the affinity, and selectivity improved with an increased amount of

34, which enabled the customization of the stability of the complex. Recently, Ganesh’s group reported that the introduction of the gem-dimethyl (

gdm) group influenced the

Z/E rotamer ratio of the tertiary amide. The

α-gdm monomer exclusively exhibits the Z-rotamer, whereas the

β-gdm monomer exhibits the

E-rotamer (

Figure 9,

35) [

87,

88]. Those

E/Z-rotamers influenced the orientation preference of PNA in the formation of the complex. The same research group also reported

aza-PNA bearing a nitrogen atom instead of a carbon atom at the α-position (

Figure 9,

36) [

89]. Interestingly, the

aza-PNA monomer assumed the

E-form via an eight-membered hydrogen-bonded ring with backbone folding. A future study will discuss how this modification impacts its target recognition.

A novel class of PNAs, bimodal PNA,

Cγ(S/R)-bm-PNA (

Figure 9,

37), was developed by Ganesh’s group [

90,

91,

92].

Cγ(S/R)-bm-PNA contains an additional nucleobase at the γ-position of the PNA backbone, which enables the bifacial recognition-forming duplexes at the B

1 and B

2 sides. The thermal stability of the DNA1/

Cγ(S/R)-bm-PNA/DNA2 complexes was higher than those of their respective isolated duplexes [

90,

91]. The other bimodal PNA,

bm-Cα-PNA (

Figure 9,

38), contains an additional nucleobase at the α-position of the PNA backbone [

92]. Additionally,

38, and 37 exhibited similar properties, although the target sequences were restricted to homothymine and homocytosine. These bimodal PNAs can be used to generate novel higher-order assemblies with DNAs and RNAs. For example, they reported the pentameric complex comprising a triplex and two duplexes, DNA1–

Cγ(S/R)-bm-PNA/DNA2–

Cγ(S/R)-bm-PNA/DNA3 [

93]. Further investigations of these new bimodal PNAs, as well as their biological applications, are anticipated.

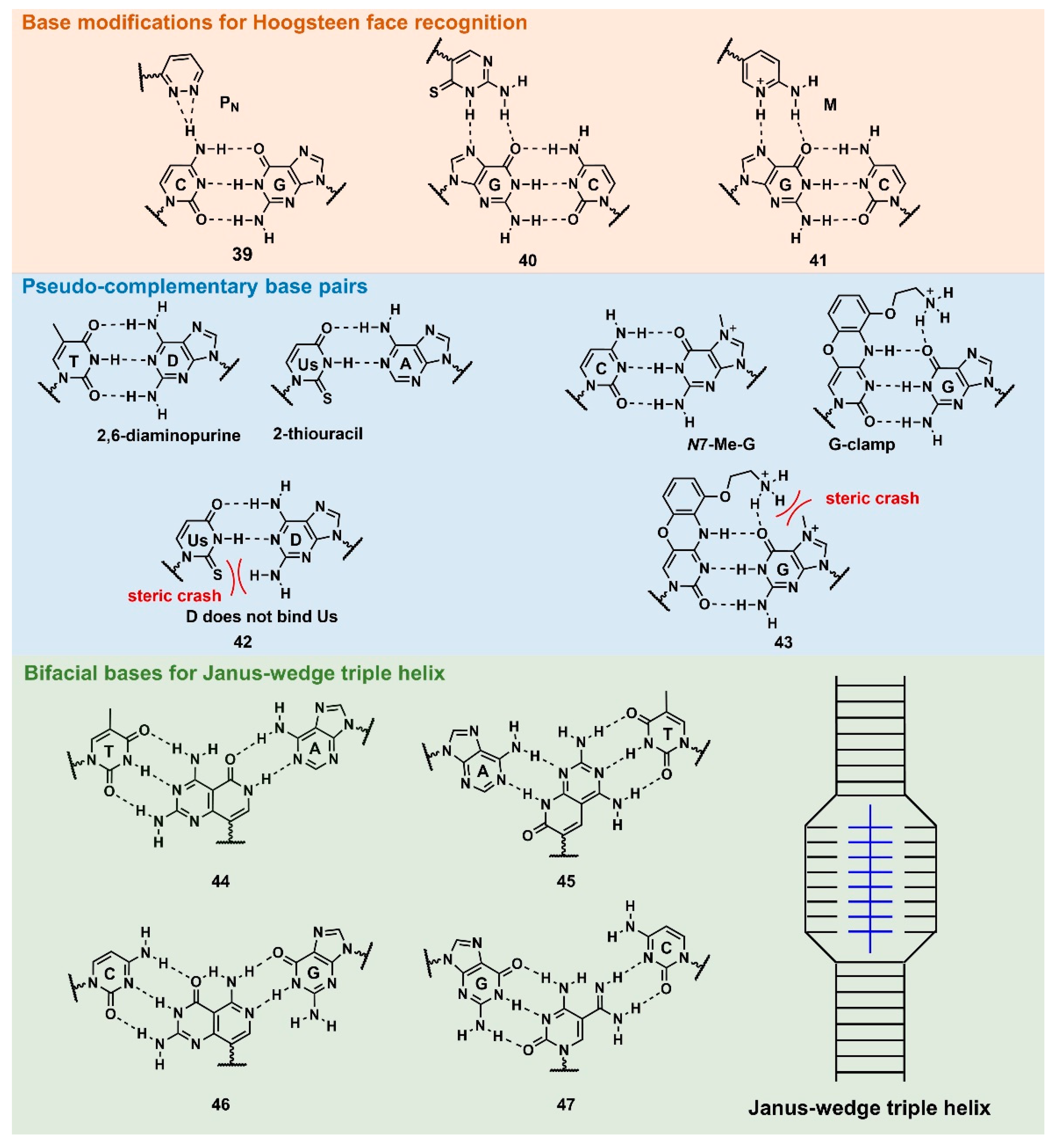

3.2.2. Base modification of peptide nucleic acid

3.2.2.1 Base modifications for enhanced triplex formation

PNA forms a triplex structure via the Hoogsteen hydrogen-bond-forming T·A:T triad and C

+·G:C triad base pairing. Therefore, the inability to form stable hydrogen bonds with the T:A and C:G base pairs, as well as the necessity of protonating C, limit their

in vivo application, including parallel TFO. Some of the designed base analogs for TFOs can be used for PNA. For example, the base analogs,

2 [

94] and

5 [

95] (

Figure 4), can be used for T:A and C:G base-pair recognition, and

5-mC,

pseudoisocytosin (

Figure 4,

12) [

96], can be used to replace C. Several artificial bases have been originally developed for PNA [

97,

98]. Recently, Rozner’s group systematically surveyed simple nitrogen heterocycles for C:G base-pair recognition and observed that 3-pyridazinyl nucleobase,

PN (

Figure 10,

39), forms more stable hydrogen bonds than the other heterocycles [

98].

The

thio-pseudoisocytosin (

Figure 10,

40) [

99] was studied by Chen’s group as a replacement for C. Here,

40 forms stable base pairing by the synergistic effect of the improved van der Waals contacts, base stacking with hydrogen-bond formation. Rozner’s group examined

2-aminopyridine M (

Figure 10,

41) as a more basic C nucleobase [

100,

101]. The replacement of six

pseudoisocytosins in 9-mer PNA comprising six

Ms increased the affinity of PNA to dsDNA by ≈100-fold owing to the cationic character of

M.

3.2.2.1. Base modifications for peptide nucleic acid functionalization

As aforementioned in

Figure 8,

D and

sU were designed to avoid the formation of the unproductive PNA–PNA duplex for pcPNA via a steric clash between the 2-amino group of

D and thiocarbonyl group of s

U (

Figure 10,

42) [

102]. Hudson’s group reported the improved synthesis of

sU, which eases the preparation of pcPNA and will accelerate future pcPNA studies [

103]. Recently, Winssinger’s group reported a new pseudocomplementary G:C base pair for

G-clamp-based dsDNA invasion (

Figure 10,

43) [

104]. G-clamp is a phenoxazine-derived tricyclic C analog that can strongly bind to G through additional interactions, such as π-stacking, the electrostatic attraction of the positively charged amine, and hydrogen bonding at the Hoogsteen face [

105]. The introduction of

G-clamp into PNA significantly improved the thermodynamic stability of the PNA/DNA duplex [

106].

They developed N-7 methylguanine (N7-Me-G) that was designed to cause steric and electrostatic repulsions between the G-clamp. The modified PNAs were demonstrated in the detection of the dsDNA target, the RT-RPA amplicon, from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), with single nucleotide resolution discriminating two SARS-CoV-2 strains. Each strand of modified PNA exhibited fast strand invasion at the physiological condition and formed stable complexes with low equivalents of PNA.

The investigation of the Janus-Wedge triple PNA helix was pioneered by McLaughlin’s group [

107]. Therein, bifacial artificial PNA nucleobases form hydrogen bonds with the Watson–Crick faces of the two DNA target strands. In 2018, Thadke’s group first reported a complete set of bifacial nucleobases that can distinguish the T:A, A:T, C:G, and G:C base pairs (

Figure 10,

44–

47) [

108,

109]. The 6-mer

miniPEG γ-modified PNA comprising these nucleobases efficiently and rapidly invaded target dsDNA with high sequence specificity under physiological conditions [

109]. As

44–

47 enabled the targeting of any sequences, they could be novel gene-targeting tools, and their applications for therapeutic purposes will be investigated subsequently.

3.2.3. Recent advancements in cross-linkable peptide nucleic acid for DNA targeting

Glazer and Nielsen’s group developed psoralen-conjugated pcPNA, demonstrating that they can be used to induce single-base substitutions and deletions within the target site [

110,

111]. The linker was only linked to the 8-position of psoralen in these PNAs, making the effect of the linker position on crosslinking formation remain elusive. Recently, our group developed novel psoralen NHS esters (

Figure 5,

21 and

22) which enabled the easy conjugation of psoralen in the

N-terminus of PNA and following photo-crosslinking evaluation [

56]. The yield of the adduct product of 5-Ps–PNA and trioxsalen–PNA prepared with

21 and

22 were 48% and 45%, respectively after 30 s of irradiation; the yields were much higher than those of corresponding PNAs prepared using

SPB (15%). The applications of these novel Ps–PNAs are being studied in our lab.

The cross-linkable furan-derived nucleobases were developed for PNA. The furan generates reactive species immediately after the activation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can be exploited for DNA crosslinking. Sequence-specific crosslinking was realized with γ-Lys-modified PNA [

112,

113]. Recently, Vilaivan’s group reported novel pyrrolidinyl PNA probes exhibiting furan as crosslinking formation with target DNA. The positional effect on crosslinking was examined, revealing that the external incorporation of the furan moiety improved the crosslinking. The future study will discuss its biological applications [

114].

3.3. Recent advancements in the therapeutic applications of peptide nucleic acids

3.3.1. Antigene

Recently, Tonelli’s group reported the therapeutic applications of PNAs in targeting the MYCN gene [

115,

116]. The PNA employed in these studies was named BGA002, which is conjugated with a nuclear localization signal peptide [

83] and specific to the MYCN gene. Although the sequence information was not disclosed, BGA002 exhibited more potent biological activities than their previous MYCN-targeting PNA (BGA001), which also exhibited antitumor activity in mice with rhabdomyosarcomas [

117]. With PNA BGA002, they targeted MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma (MNA–NB) cells in which MYCN was associated with increased ROS, downregulated mitophagy, and poor prognosis. BGA002 inhibited the expression of the MYCN gene, causing profound mitochondrial damage through the downregulation of mitochondrial molecular chaperone TRAP1; ROS increased with the concomitant decrease in the MNA–NB xenograft tumor. This research first described the relevance of MYCN in MNA–NB in mitochondrial maintenance [

115]. In the other research [

116], the combinational use of BGA002 and retinoic acid (RA) was beneficial in the treatment of MNA–NB. RA has been used to treat MNA–NB patients. However, RA resistance was observed for some patients. The coadministration of BGA002 and RA mediated the therapeutic efficacy of RA by inhibiting BGA002 on the MYCN gene. The inhibition of the MYCN gene by BGA002 decreased the mTOR pathway activity, followed by the autophagy response of MNA–NB. The efficacy of BGA002 treatment with RA was also demonstrated in an MNA–NB mouse model.

3.3.2. Genome editing

In 2016, Glazer et al. reported the

in vivo correction of a β-thalassemia mutation in mice by miniPEG γ-modified tcPNA (γtcPNA) [

118]. The γtcPNA and donor-DNA injection with poly(lacto-glycolic acid) (PLGA) NPs, as well as a stem-cell-factor treatment, ameliorated the disease phenotype and collected the β-globin gene, up to 7%, in hematopoietic stem cells. In-utero experiments have also been performed using the same mouse model, achieving improvements in the disease phenotype in pups [

119]. It seems that the tcPNA works by opening the target dsDNA via strand invasion (

Figure 8), which permits the donor DNA to hybridize the target DNA. Finally, the homology-directed repair using this donor DNA as a template resulted in gene collection [

120]. In 2022, Piotrowski-Daspit’s group further demonstrated the utility of PLGA NPs encapsulating PNA miniPEG γ-modified tcPNA and donor DNAs in cystic fibrosis (CF) treatment. CF patients experience multiorgan dysfunction, which is caused by mutations in the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene. The

in vivo correction of the CF mouse model using γtcPNA resulted in a partial gain of CFTR function and improved the phenotype [

121]. Recently, Glazer’s group also applied the same system to genome editing in single-cell embryos containing mutated eGFP genes. The blastocysts from the embryos that were treated with γtcPNA exhibited the expression of corrected eGFP with high editing levels, up to 94%. The mice from the re-implanted embryos consistently exhibited editing. This research is the first example of embryonic-gene editing using PNA [

122]. In these above experiments, gene editing was very site-specific, with considerably low levels of off-target sequence modification.

4. Conclusions and future perspectives

Our group recently described the physicochemical properties of therapeutic oligonucleotide [

1] and the DDS technologies [

2] from the symbiotic perspective. Currently, these factors are considered for RNA-targeting therapeutic oligonucleotides such as antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). We anticipate that the same technologies can be considered in the development of genome-targeting antigene nucleic acids such as TFOs, and PNAs, as introduced in this review, which offer conceptual advantages over antisense, as the antigene target is usually two gene copies per cell rather than multiple copies of mRNA that are continually undergoing transcription. Further, genome editing enables permanent changes in the pathological genes, which will result in the complete cure of diseases. Nuclease-based gene editing, such as zinc finger, CRISPR-Cas9, and TALENs, are currently being explored for therapeutic applications, although their potential off-target, cytotoxic, and/or immunogenic effects may hinder their

in vivo applications. Therefore, the potentials of TFOs, and PNAs as symbiotic genome-targeting tools cannot be ignored. Although they exhibit great therapeutic potential, several shortcomings must be addressed to achieve the application of these nucleic acids such as the limitations in the Hoogsteen-based recognition mode. As described in this review, recent advancements are overcoming these limitations, and several promising therapeutic applications have been achieved using TFO or PNA. The clinical use of these therapeutic antigene nucleic acids will cause a considerable paradigm shift in future drug development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.M. and A.Y.; investigation, Y.M.; data curation, Y.M.; resources, Y.M.; original draft preparation, Y.M. and A.Y.; supervision, Y.M. and A.Y.; writing-review and editing, Y.M. and A.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Transformative Research Areas (A) “Material Symbiosis” (Grant Number: 20H05874 to A.Y.) from MEXT, Japan. This study was also supported by JSPS KANENHI (Grant Num-ber 22H00593 to A.Y. and 22K14839 to Y.M.), Japan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest disclosed concerning the work.

References

- Terada, C.; Kawamoto, S.; Yamayoshi, A.; Yamamoto, T. Chemistry of Therapeutic Oligonucleotides That Drives Interactions with Biomolecules. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyama, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Yamayoshi, A. Recent Advances in the Delivery Carriers and Chemical Conjugation Strategies for Nucleic Acid Drugs. Cancers 2021, 13, 3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jinek, M.; Chylinski, K.; Fonfara, I.; Hauer, M.; Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. A Programmable Dual-RNA-Guided DNA Endonuclease in Adaptive Bacterial Immunity. Science 2012, 337, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modell, A.E.; Lim, D.; Nguyen, T.M.; Sreekanth, V.; Choudhary, A. CRISPR-Based Therapeutics: Current Challenges and Future Applications. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 43, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breier, D.; Peer, D. Genome Editing in Cancer: Challenges and Potential Opportunities. Bioact Mater. 2023, 21, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.C. Cas9-induced immune response: A potential caution for human genome editing. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2019, 520, 706–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duca, M.; Vekhoff, P.; Oussedik, K.; Halby, L.; Arimondo, P.B. SURVEY AND SUMMARY The triple helix: 50 years later, the outcome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 5123–5138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, P.E.; Egholm, M.; Berg, R.H.; Buchardt, O. Sequence-selective recognition of DNA by strand displacement with a thymine-substituted polyamide. Science 1991, 254, 1497–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.; Wang, G.; Vasquez, K.M. DNA Triple Helices: Biological Consequences and Therapeutic Potential. Biochimie 2008, 90, 1117–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goni, J.R.; Vaquerizas, J.M.; Dopazo, J.; Orozco, M. Exploring the Reasons for the Large Density of Triplex-Forming Oligonucleotide Target Sequences in the Human Regulatory Regions. BMC Genomics 2006, 7, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaddis, S.S.; Wu, Q.; Thames, H.D.; Digiovanni, J.; Walborg, E.F.; Macleod, M.C.; Vasquez, K.M. A Web-Based Search Engine for Triplex-Forming Oligonucleotide Target Sequences. Oligonucleotides 2006, 16, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenjaroenpun, P.; Kuznetsov, V.A. TTS Mapping: Integrative WEB Tool for Analysis of Triplex Formation Target DNA Sequences, G-quadruplets and Non-Protein Coding Regulatory DNA Elements in the Human Genome. BMC Genomics 2009, 10, S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenjaroenpun, P.; Chew, C.S.; Yong, T.P.; Choowongkomon, K.; Thammasorn, W.; Kuznetsov, V.A. The TTSMI Database: A Catalog of Triplex Target DNA Sites Associated with Genes and Regulatory Elements in the Human Genome. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, D110–D116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhou, Z.; Ren, C.; Deng, Y.; Peng, F.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, Y. Triplex-Forming Oligonucleotides as An Anti-Gene Technique for Cancer Therapy. Front. Pharmacol 2022, 13, 1007723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewett, P.W.; Daft, E.L.; Laughton, C.A.; Ahmad, S.; Ahmed, A.; Murray, J.C. Selective Inhibition of the Human Tie-1 Promoter with Triplex-Forming Oligonucleotides Targeted to Ets Binding Sites. Mol. Med. 2006, 12, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karympalis, V.; Kalopita, K.; Zarros, A.; Carageorgiou, H. Regulation of Gene Expression via Triple Helical Formations. Biochemistry, 2004, 69, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, S.L.; Krawczyk, S.H.; Matteucci, M.D.; Toole, J.J. Triple Helix Formation Inhibits Transcription Elongation in Vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991, 88, 10023–10026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, H.E.; Dervan, P.B. Sequence-Specific Cleavage of Double Helical DNA by Triple Helix Formation. Science 1987, 238, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruqi, A.F.; Seidman, M.M.; Segal, D.J.; Carroll, D.; Glazer, P.M. Recombination Induced by Triple-Helix-Targeted DNA Damage in Mammalian Cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1996, 16, 6820–6828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushik Tiwari, M.; Rogers, F.A. XPD-dependent activation of apoptosis in response to triplex-induced DNA damage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 8979–8994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik Tiwari, M.; Colon-Rios, D.A.; Rao Tumu, H.C.; Liu, Y.; Quijano, E.; Krysztofiak, A.; Chan, C.; Song, E.; Braddock, D.T.; Suh, H.-W.; Saltzman, W.M.; Rogers, F.A. Direct Targeting of Amplified Gene Loci for Proapoptotic Anticancer Therapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushik Tiwari, M.; Adaku, N.; Peart, N.; Rogers, F.A. Triplex Structures Induce DNA Double Strand Breaks via Replication Fork Collapse in NER Deficient Cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 7742–7754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faria, M.; Wood, C.D.; Perrouault, L.; Nelson, J.S.; Winter, A.; White, M.R.H.; Hélène, C.; Giovannangeli, C. Targeted inhibition of transcription elongation in cells mediated by triplex-forming oligonucleotides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000, 97, 3862–3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenyuk, A.; Darian, E.; Liu, J.; Majumdar, A.; Cuenoud, B.; Miller, P.S.; MacKerell, A.D., Jr.; Seidman, M.M. Targeting of an interrupted polypurine:polypyrimidine sequence in mammalian cells by a triplex-forming oligonucleotide containing a novel base analogue. Biochemistry. 2010, 49, 7867–7878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hari, Y.; Obika, S.; Imanishi, T. Towards the Sequence-Selective Recognition of Double-Stranded DNA Containing Pyrimidine-Purine Interruptions by Triplex-Forming Oligonucleotides. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 2875–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, L.C.; Dervan, P.B. Recognition of thymine adenine.base pairs by guanine in a pyrimidine triple helix motif. Science 1989, 245, 967–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.; Hobbs, C.A.; Koch, J.; Sardaro, M.; Kutny, R.; Weis, A.L. Elucidation of the sequence-specific third-strand recognition of four Watson-Crick base pairs in a pyrimidine triple-helix: T.AT, C.GC, T.CG, and Gn.TA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992, 89, 3840–3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.; Miller, P.S. Interactions of Cytosine Derivatives with T·A Interruptions in Pyrimidine·Purine·Pyrimidine DNA Triplex. Bioconjugate Chem. 1996, 7, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guianvarc’h, D.; Benhida, R.; Fourrey, J.L.; Maurisse, R.; Sun, J.S. Incorporation of a novel nucleobase allows stable oligonucleotide-directed triple helix formation at the target sequence containing a purine·pyrimidine interruption. Chem. Commun. 2001, 1814–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkubo, A.; Ohnishi, T.; Nishizawa, S.; Nishimura, Y.; Hisamatsu, S. The ability of a triplex-forming oligonucleotide to recognize T-A and C-G base pairs in a DNA duplex is enhanced by incorporating N-acetyl-2,7-diaminoquinoline. Bioorg Med Chem. 2020, 28, 115350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerrard, S.R.; Edrees, M.M.; Bouamaied, I.; Fox, K.R.; Brown, T. CG base pair recognition within DNA triple helices by modified N-methylpyrrolo-dC nucleosides. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010, 8, 5087–5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hari, Y.; Akabane, M.; Obika, S. 2’-4’-BNA bearing a chiral guanidinopyrrolidine-containing nucleobase with potent ability to recognize the C:G base pair in a parallel-motif DNA triplex. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 7421–7423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obika, S.; Uneda, T.; Sugimoto, T.; Nanbu, D.; Minami, T.; Doi, T.; Imanishi, T. 2’-O,4’-C-methylene bridge nucleic acid (2’,4’-BNA): synthesis and triplex-forming properties. Bioorg Med Chem. 2001, 9, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taniguchi, Y.; Magata, Y.; Osuki, T.; Notomi, R.; Wang, L.; Okamura, H.; Sasaki, S. Development of novel C-nucleoside analogues for the formation of antiparallel-type triplex DNA with duplex DNA that includes TA and dUA base pairs. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 2845–2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishizawa, S.; Tu, G.; Ogata, D.; Miyauchi, K.; Ohkubu, A. Development of antiparallel-type triplex-forming oligonucleotides containing quinoline derivatives capable of recognizing a T-A base pair in a DNA duplex. Bioorg Med Chem. 2022, 71, 116934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Taniguchi, Y.; Okamura, H.; Sasaki, S. Modification of the aminopyridine unit of 2’-deoxyaminopyridinyl-pseudocytidine allowing triplex formation at CG interruptions in homopurine sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 8679–8688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notomi, R.; Wang, L.; Osuki, T.; Okamura, H.; Sasaki, S.; Taniguchi, Y. Synthesis of C-nucleoside analogues based on the pyrimidine skeleton for the formation of anti-parallel-type triplex DNA with a CG mismatch site. Bioorg Med Chem. 2020, 28, 115782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notomi, R.; Wang, L.; Sasaki, S.; Taniguchi, Y. Design and synthesis of purine nucleoside analogues for the formation of stable anti-parallel-type triplex DNA with duplex DNA bearing the 5mCG base pair. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 21390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notomi, R.; Sasaki, S.; Taniguchi, Y. Recognition of 5-methyl-CG and CG base pairs in duplex DNA with high stability using antiparallel-type triplex-forming oligonucleotides with 2-guanidinoethyl-2’-deoxynebularine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 12071–12081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartono, Y.D.; Pabon-Martinez, Y.V.; Uyar, A.; Wengel, J.K.; Lundin, K.E.; Zain, R.; Smith, C.I.E.; Nilsson, L.; Villa, A. Role of pseudoisocytosine tautomerization in triplex-forming oligonucleotides: in silico and in vitro studies. ACS Omega. 2017, 2, 2165–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusling, D.A. Triplex-forming properties and enzymatic incorporation of a base-modified nucleotide capable of duplex DNA recognition at neutral pH. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 7256–7266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, S.; Taniguchi, Y.; Takahashi, R.; Senko, Y.; Kodama, K.; Nagatsugi, F.; Maeda, M. Selective Formation of Stable Triplexes Including a TA or a CG Interrupting Site with New Bicyclic Nucleoside Analogue (WNA). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 516–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inde, T.; Nishizawa, S.; Hattori, Y.; Kanamori, T.; Yuasa, H.; Seio, K.; Sekine, M.; Ohkubo, A. Synthesis of and triplex formation in oligonucleotides containing 2’-deoxy-6-thioxanthosine. Bioorg Med Chem. 2018, 26, 3785–3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, E.; Koshlap, K.M.; Gillespie, P.; Dervan, P.B.; Feigon, J. Solution Structure of a Pyrimidine·Purine·Pyrimidine Triplex Containing the Sequence-specific Intercalating Non-natural Base D3. J. Mol. Biol. 1996, 257, 1052–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, G.M.; McGuffie, E.; Napoli, S.; Flanagan, C.E.; Dembech, C.; Negri, U.; Arcamone, F.; Capobianco, M.L.; Catapano, C.V. DNA binding and antigene activity of a daunomycin-conjugated triplex-forming oligonucleotide targeting the P2 promoter of the human c-myc gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 2396–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, K.R.; Brown, T.; Rusling, D.A. DNA recognition by parallel triplex formation. In: Waring, M.J. (ed). DNA-Targeting Molecules as Therapeutic Agents. RSC Publishing. 2018, Cambridge, 1-32.

- Walsh, S.; El-Sagheer, A.H.; Brown, T. Fluorogenic thiazole orange TOTFO probes stabilize parallel DNA triplexes at pH 7 and above. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 7681–7687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, K.; Ramachandran, V.; Fassihi, H.; Sebaratnam, F.D. Comparison of Narrowband UV-B With Psoralen-UV-A Phototherapy for Patients With Early-Stage Mycosis Fungoides: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019, 155, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhimschi, D.A.; Gooden, M.D.; Jing, H.; Fels, R.D.; Hansen, S.K.; Beyer, F.W.; Dewhirst, W.M.; Walder, H.; Gasparro, P.F. Psoralen Derivatives with Enhanced Potency. Photochem. Photobiol. 2020, 96, 1014–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval-Valentin, G.; Thuong, N.T.; Hélène, C. Specific Inhibition of Transcription by Triple Helix-Forming Oligonucleotide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1992, 89, 504–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havre, P.A.; Gunther, E.; Gasparro, F.; Glazer, P.M. Targeted Mutagenesis of DNA Using Triple Helix-Forming Oligonucleotides Linked to Psoralen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 1993, 90, 7879–7883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raha, M.; Lacroix, L.; Glazer, P.M. Mutagenesis Mediated by Triple Helix-Forming Oligonucleotides Conjugated to Psoralen: Effects of Linker Arm Length and Sequence Context. Photochem. Photobiol. 1998, 67, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, A.; Muniandy, P. A.; Liu, J.; Liu, J.-I.; Liu, S.-T.; Cuenoud, B.; Seidman, M. M. Targeted Gene Knock-In and Sequence Modulation Mediated by a Psoralen-Linked Triplex-Forming Oligonucleotide. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 11244–11252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Majumdar, A.; Liu, J.; Thompson, L.H.; Seidman, M.M. Sequence Conversion by Single Strand Oligonucleotide Donors via Non-homologous End Joining in Mammalian Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 23198–23207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, A.; Nakao, J.; Shimada, N.; Yoshida, N.; Abe, Y.; Mikame, Y.; Yamamoto, T.; Wada, T.; Maruyama, A.; Yamayoshi, A. Selective Photo-Crosslinking Detection of Methylated Cytosine in DNA Duplex Aided by a Cationic Comb-Type Copolymer. ACS. Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 8, 1799–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, J.; Mikame, Y.; Eshima, H.; Yamamoto, T.; Dohno, C.; Wada, T.; Yamayoshi, A. Unique Crosslinking Properties of Psoralen-Conjugated Oligonucleotides Developed by Novel Psoralen N-Hydroxysuccinimide Esters. ChemBioChem. 2023, e202200789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, J.; Yamamoto, T.; Yamayoshi, A. Therapeutic Application of Sequence-Specific Binding Molecules for Novel Genome Editing Tools. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2022, 42, 100427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.M.; Lippard, S.J. Cisplatin: from DNA Damage to Cancer Chemotherapy. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 2001, 67, 93–130. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.K.; McLaughlin, L.W. Cross-Linking of a DNA Conjugate Tethering a cis-Bifunctional Platinated Complex to a Target DNA Duplex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 9658–9659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, M.K.; Miller, P.S. Inhibition of Transcription by Platinated Triplex-Forming Oligonucleotides. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 17, 1197–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.K.; Brown, T.R.; Miller, P.S. Targeting the Human Androgen Receptor Gene with Platinated Triplex-Forming Oligonucleotides. Biochemistry. 2015, 54, 2270–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennessy, J.; McGorman, B.; Molphy, Z.; Farrell, N.P.; Singleton, D.; Brown, T.; Kellett, A. A Click Chemistry Approach to Targeted DNA Crosslinking with cis-Platinum(Ⅱ)-Modified Triplex-Forming Oligonucleotides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Fantoni, N.Z.; Brown, T.; Kellett, A. DNA-Targeted Metallodrugs: An Untapped Source of Artificial Gene Editing Technology. ChemBioChem. 2021, 22, 2184–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panattoni, A.; El-Sagheer, A.H.; Kellett, A.; Hocek, M. Oxidative DNA Cleavage with Clip-Phenanthroline Triplex-Forming Oligonucleotide Hybrids. ChemBioChem. 2020, 21, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauria, T.; Slator, C.; McKee, V.; Müller, M.; Stazzoni, S.; Crisp, A.L.; Carell, T.; Kellett, A. A Click Chemistry Approach to Developing Molecularly Targeted DNA Scissors. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 16782–16792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantoni, N.Z.; McGorman, B.; Molphy, Z.; Singleton, D.; Walsh, S.; El-Sagheer, A.H.; McKee, V.; Brown, T.; Kellett, A. Development of Gene-Targeted Polypyridyl Triplex-Forming Oligonucleotide Hybrids. ChemBioChem. 2020, 21, 3563–3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGorman, B.; Fantoni, N.Z.; O’Carroll, S.; Ziemele, A.; El-Sagheer, A.H.; Brown, T.; Kellett, A. Enzymatic Synthesis of Chemical Nucleoase Triplex-Forming Oligonucleotides with Gene-Silencing Application. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 5467–5481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquet, J.; Henrionnet, C.; Pinzano, A.; Vincourt, J.B.; Gillet, P.; Netter, P.; Chary-Valckenaere, I.; Loeuille, D.; Pourel, J.; Grossin, L. Alternative for Anti-TNF Antibodies for Arthritis Treatment. Molecular Therapy 2011, 19, 1887–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, S.; Gong, N.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, F.; Guo, H.; Gan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Herrmann, A.; Liang, X.J. Gold-DNA nanosunflowers for efficient gene silencing with controllable transformation. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw6264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, M. K.; Colon-Rios, D.A; Tumu, H.C.R.; Liu, Y.; Quijano, E.; Krysztofiak, A.; Chan, C.; Song, E.; Braddock, D.T.; Suh, H.W.; Saltzman, W.A.; Rogers, F.A. Direct targeting of amplified gene loci for proapoptotic anticancer therapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xu, Y.; Fu, J.; Shen, Z. Nanoparticle delivery of TFOs is a novel targeted therapy for HER2 amplified breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2023, 23, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, P.; Egholm, M.; Berg, R.; Buchardt, O. Sequence-Selective Recognition of DNA by Strand Displacement with a Thymine-Substituted Polyamide. Science 1991, 254, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Pradhan, B. Evolution of peptide nucleic acid with modifications of its backbone and application in biotechnology. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2021, 97, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonkar, P.; Kim, K.H.; Kuan, J.Y.; Chin, J.Y.; Rogers, F.A.; Knauert, M.P.; Kole, P.; Nielsen, P.E.; Glazer, P.M. Targeted correction of a thalassemia-associated β-globin mutation induced by pseudo-complementary peptide nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 3635–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, F.A.; Vasquez, K.M.; Egholm, M.; Glazer, P.M. Site-directed recombination via bifunctional PNA-DNA conjugates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002, 99, 16695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleifman, E.B.; Bindra, R.; Leif, J.; del Campo, J.; Rogers, F.A.; Uchil, P.; Kutsch, O.; Shultz, L.D.; Kumar, P.; Greiner, D.L.; Glazer, P.M. Targeted Disruption of the CCR5 Gene in Human Hematopoietic Stem Cells Stimulated by Peptide Nucleic Acids. Chem. Biol. 2011, 18, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, J.D.R.; Carufe, K.E.W.; Glazer, P.M. Peptide nucleic acids and their role in gene regulation and editing. Biopolymers. 2021, e23460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swenson, C.S.; Heemstra, J.M. Peptide nucleic acids harness dual information codes in a single molecule. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suparpprom, C.; Vilaivan, T. Perspectives on conformationally constrained peptide nucleic acid (PNA): insights into the structural design, properties and applications. RSC Chem. Biol. 2022, 3, 648–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodyagin, N.; Katkevics, M.; Kotikam, V.; Ryan, C.A.; Rozners, E. Chemical approaches to discover the full potential of peptide nucleic acids in biomedical applications. Beilstein. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 17, 1641–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragulescu-Andrasi, A.; Rapireddy, S.; Frezza, B.M.; Gayathri, C.; Gil, R.R.; Ly, D.H. A Simple γ-Backbone Modification Preorganizes Peptide Nucleic Acid into a Helical Structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 10258–10267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, B.; Chenna, V.; Lathrop, K.L. : Thomas, S.M.; Zon, G.; Livak, K.J.; Ly, D.H. Synthesis of Conformationally Preorganized and Cell-Permeable Guanidine-Based γ-Peptide Nucleic Acids (γ-GPNAs). J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 1509–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahal, R.; Sahu, B.; Rapireddy, S.; Lee, C.M.; Ly, D. H. Sequence-Unrestricted, Watson-Crick Recognition of Double Helical B-DNA by (R)-MiniPEG-γPNAs. ChemBioChem. 2012 13, 56–60. [CrossRef]

- Tähtinen, V.; Verhassel, A.; Tuomela, J.; Virta, p. γ-(S)-Guanidinylmethyl-Modified Triplex-Forming Peptide Nucleic Acids Increase Hoogsteen-Face Affinity for a MicroRNA and Enhanced Cellular Uptake. ChemBioChem. 2019, 20, 3041–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Saha, M.; Appella, D.H. Synthesis of Fmoc-Protected (S,S)-trans-Cyclopentane Diamine Monomers Enables the Preparation and Study of Conformationally Restricted Peptide Nucleic Acids. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 7637–7640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Botos, I.; Clausse, V.; Nikolayevskiy, H.; Rastede, E.E.; Fouz, M.F.; Mazur, S.J.; Appella, D.H. Conformational constraints of cyclopentane peptide nucleic acids facilitate tunable binding to DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, P.; Datta, D.; Ramabhadran, R.O.; Ganesh, K.N. Gem-dimethyl peptide nucleic acid (α/β/γ-gdm-PNA) monomers: synthesis and the role of gdm-substituents in preferential stabilization of Z/E-rotamers. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19, 6534–6545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, P.; Datta, D.; Ramabhadran, R.O.; Ganesh, K.N. Gemdimethyl Peptide Nucleic Acids (α/β/γ-gdm-PNA): E/Z-Rotamers Influence the Selectivity in the Formation of Parallel/Antiparallel gdm-PNA:DNA/RNA Duplexes. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 40558–40568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraj, A.; Ramabhadran, R.O.; Ganesh, K.N. Aza-PNA: Engineering E-Rotamer Selectivity Directed by Intramolecular H-Bonding. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 7421–7427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhingardeve, P.; Madhanagopal, B.R.; Ganesh, K.N. Cγ-(S/R)-Bimodal Peptide Nucleic Acids (Cγ-bm-PNA) Form Coupled Double Duplexes by Synchronous Binding to Two Complementary DNA Strands. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 13680–13693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.K.; Madhanagopal, B.R.; Datta, D.; Ganesh, K.N. Structural Design and Synthesis of Bimodal PNA That Simultaneously Binds Two Complementary DNAs To Form Fused Double Duplexes. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 5255–5260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, M.K.; Madhanagopal, B.R.; Ganesh, K.N. Peptide Nucleic Acid with Double Face: Homothymine-Homocytosine Bimodal Cα-PNA (bm-Cα-PNA) Forms a Double Duplex of the bm-PNA2:DNA Tripolex. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 414–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhingardeve, P.; Jain, P.; Ganesh, K.N. Molecular Assembly of Triplex of Duplexes from Homothyminyl-Homocytosinyl Cγ-(S/R)-Bimodal Peptide Nucleic Acids with dA/dG and the Cell Permeability of Bimodal Peptide Nucleic Acids. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 19757–19770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, A. A. L.; Toh, D.F.K.; Patil, K.M.; Meng, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Krishna, M.S.; Devi, G.; Haruehanroengra, P.; Lu, Y.; Xia, K.; Okamura, K.; Sheng, J.; Chen, G. General Recognition of U-G, U-A, and C-G Pairs by Double-Stranded RNA-Binding PNAs Incorporated with an Artificial Nucleobase. Biochemistry. 2019, 58, 1319–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, D.F.K.; Devi, G.; Patil, K.M.; Qu, Q.; Maraswami, M.; Xiao, Y.; Loh, T.P.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, G. Incorporating a guanidine-modified cytosine base into triplex-forming PNAs for the recognition of a C-G pyrimidine-purine inversion site of an RNA duplex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 9071–9082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egholm, M.; Christensen, L.; Deuholm, K.L.; Buchardt, O.; Coull, J.; Nielsen, P.E. Efficient pH-independent sequence-specific DNA binding by pseudoisocytosine-containing bis-PNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995, 23, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumpina, I.; Brodyagin, N.; MacKay, J.A.; Kennedy, S.D.; Katkevics, M.; Rozners, E. Synthesis and RNA-Binding Properties of Extended Nucleobases for Triplex-Forming Peptide Nucleic Acids. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 13276–13298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodyagin, N.; Kumpina, I.; Applegate, J.; Katkevics, M.; Rozners, E. Pyridazine Nucleobase in Triplex-Forming PNA Improves Recognition of Cytosine Interruptions of Polypurine Tracts in RNA. ACS Chem. Biol. 2021, 16, 872–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devi, G.; Yuan, Z.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, G. Incorporation of thio-pseudoisocytosine into triplex-forming peptide nucleic acids for enhanced recognition of RNA duplexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 4008–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotikam, V.; Kennedy, S.; MacKay, J.A.; Rozners, E. Synthetic, Structural, and RNA Binding Studies on 2-Aminopyridine-Modified Triplex-Forming Peptide Nucleic Acids. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 4367–4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, C.A.; Brodyagin, N.; Lok, J.; Rozners, E. The 2-Aminopyridine Nucleobase Improves Triple-Helical Recognition of RNA and DNA When Used Instead of Pseudoisocytosine in Peptide Nucleic Acids. Biochemistry. 2021, 60, 1919–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaima, G.; Hansen, H.F.; Christensen, L.; Dahl, O.; Nielsen, P.E. Increased DNA binding and sequence discrimination of PNA oligomers containing 2,6-diaminopurine. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 4639–4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, R.H.E.; Heidari, A.; Martin-Chan, T.; Park, G.; Wisner, J.A. On the Necessity of Nucleobase Protection for 2-Thiouracil for Fmoc-Based Pseudo-Complementary Peptide Nucleic Acid Oligomer Synthesis. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 13252–13261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Tena, M.; Farrera-Soler, L.; Barluenga, S.; Winssinger, N. Pseudo-Complementary G:C Base Pair for Mixed Sequence dsDNA Invasion and Its Applications in Diagnostics (SARS-CoV-2 Detection). JACS Au. 2023, 3, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, K.Y.; Matteucci, M.D. A Cytosine Analogue Capable of Clamp-Like Binding to a Guanine in Helical Nucleic Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 8531–8532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeev, K.G.; Maier, M.A.; Lesnik, E.A. High-Affinity Peptide Nucleic Acid Oligomers Containing Tricyclic Cytosine Analogues. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 4395–4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Meena; Sharma, S. K.; McLaughlin, L.W. Formation and Stability of a Janus-Wedge Type of DNA Triple. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 70–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thadke, S.A.; Perera, J.D.R.; Hridya, V.M.; Bhatt, K.; Shaikh, A.Y.; Hsieh, W. C.; Chen, M.; Gayathri, C.; Gil, R.R.; Rule, G.S.; Mukherjee, A.; Thornton, C.A.; Ly, D.H. Design of Bivalent Nucleic Acid Ligands for Recognition of RNA-Repeated Expansion Associated with Huntington’s Disease. Biochemistry. 2018, 57, 2094–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thadke, S.A.; Hridya, V.M.; Perera, J.D.R.; Gil, R.R.; Mukherjee, A.; Ly, D.H. Shape selective bifacial recognition of double helical DNA. Commun. Chem. 2018, 1, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Fan, X.J.; Nielsen, P.E. Efficient Sequence-Directed Psoralen Targeting Using Pseudocomplementary Peptide Nucleic Acids. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007, 18, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.H.; Nielsen, P.E.; Glazer, P.M. Site-directed gene mutation at mixed sequence targets by psoralen-conjugated pseudo-complementary peptide nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 7604–7613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manicardi, A.; Gyssels, E.; Corradini, R.; Madder, A. Furan-PNA: a mildly inducible irreversible interstrand crosslinking system targeting single and double-stranded DNA. Chem Commun. 2016, 52, 6930–6933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elskens, J.; Manicardi, A.; Costi, V.; Madder, A.; Corradini, R. Synthesis and improved cross-linking properties of C5-modified furan bearing PNAs. Molecules 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muangkaew, P.; Vilaivan, T. Pyrrolidinyl Peptide Nucleic Acid Probes Capable of Crosslinking with DNA: Effects of Terminal and Internal Modifications on Crosslink Efficiency. ChemBioChem. 2021, 22, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montemurro, L.; Raieli, S.; Angelucci, S.; Bartolucci, D.; Amadesi, C.; Lampis, S.; Scardovi, A.L.; Venturelli, L.; Nieddu, G.; Cerisoli, L.; Fischer, M.; Teti, G.; Falconi, M.; Pession, A.; Hrelia, P.; Tonelli, R. A Novel MYCN-Specific Antigene Oligonucleotide Deregulates Mitochondria and Inhibits Tumor Growth in MYCN-Amplified Neuroblastome. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 6166–6177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampis, S.; Raieli, S.; Montemurro, L.; Bartolucci, D.; Amadesi, C.; Bortolotti, S.; Angelucci, S.; Scardovi, A.L.; Nieddu, G.; Cerisoli, L.; Paganelli, F.; Valante, S.; Fischer, M.; Martelli, A.M.; Pasquinelli, G.; Pession, A.; Hrelia, P.; Tonelli, R. The MYCN inhibitor BGA002 restores the retinoic acid response leading to differentiation or apoptosis by the mTOR block in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022, 42, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonelli, R.; Mclntyre, A.; Camerin, C.; Walters, Z.S.; Leo, K.D.; Selfe, J.; Purgato, S.; Missiaglia, E.; Tortori, A.; Renshaw, J.; Astolfi, A.; Taylor, K.R.; Serravalle, S.; Bishop, R.; Nanni, C.; Valentijn, L.J.; Faccini, A.; Leuschner, I.; Formica, S.; Reis-Filho, J.S.; Ambrosini, V.; Thway, K.; Franzoni, M.; Summersgill, B.; Marchelli, R.; Hrelia, P.; Cantelli-Forti, G.; Fanti, S.; Corradini, R.; Pession, A.; Shipley, J. Antitumor Activity of Sustauned N-Myc Reduction in Rhabdomyosarcomas and Transcriptional Block by Antigene Therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 796–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahal, R.; Ali McNeer, N.; Quijano, E.; Liu, Y.; Sulkowski, P.; Turchick, A.; Lu, Y.C.; Bhunia, D.C.; Manna, A.; Greiner, D.L.; Brehm, M.A.; Cheng, C.J.; López-Giráldez, F.; Ricciardi, A.; Beloor, J.; Krause, D.S.; Kumar, P.; Gallagher, P.G.; Braddock, D.T.; Mark Saltzman, W.; Ly, D.H.; Glazer, P.M. In vivo correction of anaemia in β-thalassemic mice by γPNA-mediated gene editing with nanoparticle delivery. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciardi, A.S.; Bahal, R.; Farrelly, J.S; Quijano, E.; Bianchi, A.H.; Luks, V.L.; Putman, R.; López-Giráldez, F.; Coskun, S.; Song, E.; Liu, Y.; Hsieh, W.C.; Ly, D.H.; Stitelman, D.H.; Glazer, P.M.; Saltzman, W.M. In utero nanoparticle delivery for site-specific genome editing. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, J.Y.; Glazer, P.M. Repair of DNA lesions associated with triplex-forming oligonucleotides. Mol Carcinog. 2009, 48, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piotrowski-Daspit, A.S.; Barone, C.; Lin, C.Y.; Deng, Y.; Wu, D.; Binns, T.C.; Xu, E.; Ricciardi, A.S.; Putman, R.; Garrison, A.; Nguyen, R.; Gupta, A.; Fan, R.; Glazer, P.M.; Saltzman, W.M.; Egan, M.E. In vivo correction of cystic fibrosis mediated by PNA nanoparticles. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabo0522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putman, R.; Ricciardi, A.S.; Carufe, K.E.W.; Quijano, E.; Bahal, R.; Glazer, P.M.; Saltzman, W.M. Nanoparticle-mediated genome editing in single-cell embryos via peptide nucleic acids. Bioeng Transl Med. 2023, 8, e10458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).