Submitted:

17 September 2023

Posted:

18 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature and hypothesis development

| Theories | Explanations | Hypothesis/Variable affected |

| Agency theory | Theorizes that investors (principles) delegate the task of running a firm to the company's managers. Efficient corporate governance can minimize resulting agency costs |

CSR Committee CSR Executive BoD female percentage |

| Legitimacy theory | Predicts that to get resources and be accepted,organization has to comply with its social contract. Argues that companies employ sustainability disclosure to improve the public perception of their sustainability performance. Poorly performing companies use sustainability disclosure as a legitimation strategy to influence public perceptions of their sustainability performance |

GRI standards DJSI constituent TCFD reports UN Global Compact CSR Committee CSR Executive |

| Signaling theory | Predicts that companies publish information to influence potential shareholders |

GRI standards TCFD reports UN Global Compact Climate transition plan DJSI constituent |

| Stakeholder theory | Predicts that companies publish information to influence/inform stakeholders |

GRI standards UN Global Compact Climate transition plan CSR Committee DJSI constituent TCFD reports |

| Institutional theory | Theorizes that company is part of social system/structure and has to act a certain way to be accepted |

Developed vs. emerging country Climate transition plan ESG reporting CSR Committee CSR Executive |

| Voluntary disclosure theory | Predicts that a company with good performance is incentivized to disclose information regarding its performance to increase its market value; bad performers try to greenwash |

GRI standards UN Global Compact Climate transition plan CSR Committee CSR Executive DJSI constituent TCFD reports MSCI ESG ranking |

| Geert Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions theory | Predicts differences between different cultures as well as between developments statuses of countries |

Developed vs emerging country BoD female percentage CSR Executive |

| Gender socialization theory | Predicts that females behave differently, also in context as board member | BoD female percentage |

| Resource dependence theory | Predicts that board of directors provides firms unique resources and capabilities | BoD female percentage |

| Upper echelon theory | Predicts that directors’ demographic characteristics and experiences shape their values and behaviours→females behave differently | BoD female percentage |

| Social Innovation theory | Predicts that organizations distribute value and collective impact to address social problems. | Developed vs emerging country |

| Research-based | ||

| Not based on theory |

Research results suggest that factor “size” is significant determinant of companies’ CSR disclosure practices [148] [149]. Kup et al. [150] examined Chinese companies' CSR and sustainability reports, demonstrating that larger firms are likely to disclose more CE information to meet stakeholders' expectations. |

Size |

| Research results suggest that factor “industry” is significant determinants of companies’ CSR disclosure practices [151] [152] [153]. | Extractive vs Non-extractive Industry | |

| Research results suggest that ratio of “female directors” influence climate change innovation mainly through their involvement in management as executive directors, rather than through the monitoring and advisory roles that characterize independent directors [154]. | BoD female percentage | |

| Research results suggest that factors such as legitimacy concerns are significant determinants of companies’ CSR disclosure practices [155] [156] [157] [158] [159] [160]. |

MSCI ESG ranking Indirectly: DJSI constituent TCFD reports UN Global Compact |

|

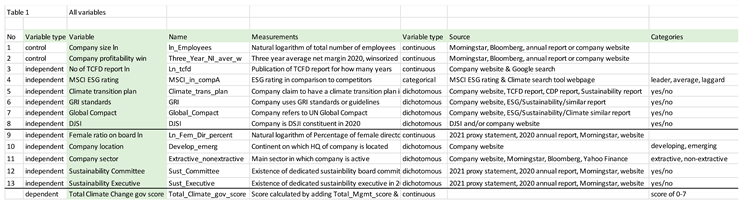

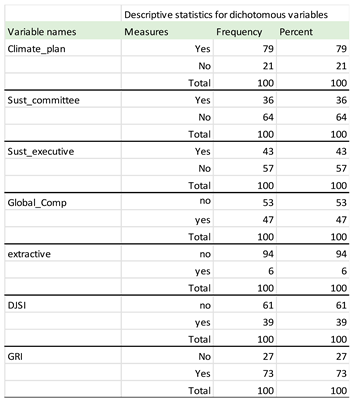

3. Research methodology and data

3.1. Sample

|

|

|

3.2. Empirical Model

4. Results

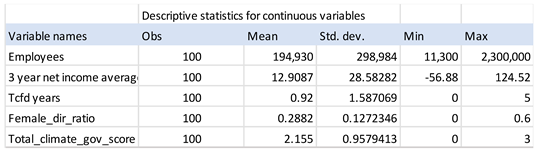

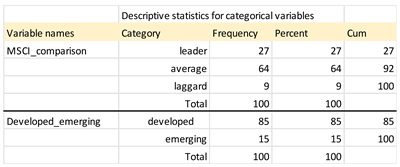

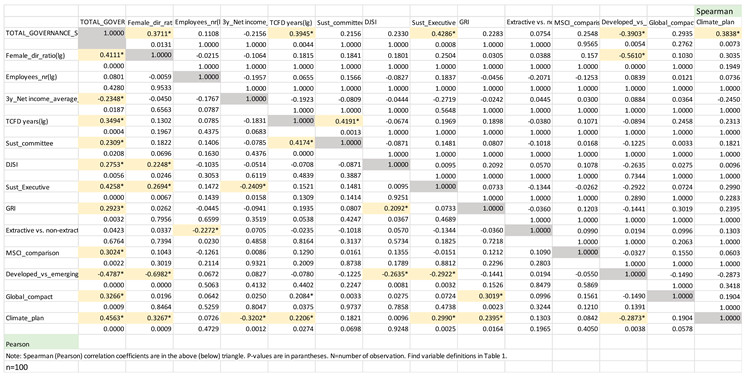

4.1. Correlation analysis

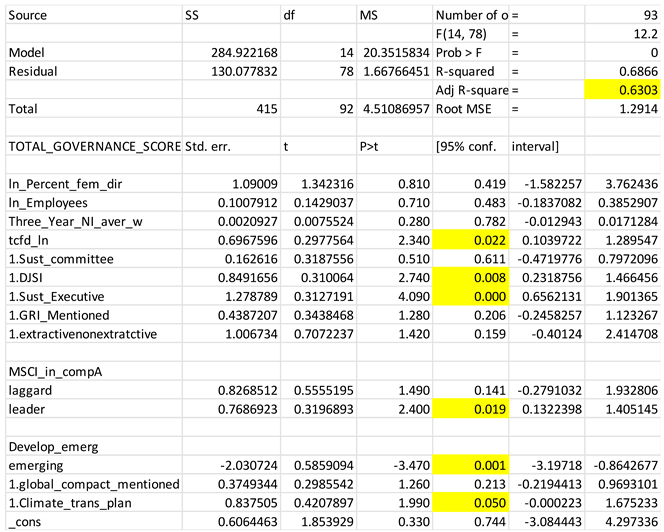

4.3. Multivariate results

|

4.4. Data Robustness

5. Discussion & Conclusion

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix

|

References

- Boyd, Natasha. “Top Business Sustainability Issues of 2023 .” Network for Business Sustainability (NBS), 29 Apr. 2023, www.nbs.net/top-business-sustainability-issues-of-2023/?utm_source=Master%2BList&utm_campaign=9a17aa531e-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2020_01_22_06_29_COPY_01&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_44e73b0e1c-9a17aa531e-52185613.

- “What Is Climate Change?” United Nations, www.un.org/en/climatechange/what-is-climate-change. Accessed 25 Apr. 2023.

- See 2.

- “Past Eight Years Confirmed to Be the Eight Warmest on Record.” World Meteorological Organization, 12 Jan. 2023, www.public.wmo.int/en/media/press-release/past-eight-years-confirmed-be-eight-warmest-record.

- “Climate Change 2023.” AR6 Synthesis Report, www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/. Accessed 25 Apr. 2023.

- See 4.

- See 5.

- “Raising Awareness on Climate Change and Health.” World Health Organization (WHO), www.who.int/europe/activities/raising-awareness-on-climate-change-and-health. Accessed 25 Apr. 2023.

- Nagy, D. M., & Williams, C. A. (2022, March 25). ESG and climate change blind spots: Turning the corner on SEC disclosure. SSRN. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4049878.

- “Homepage: UN Global Compact.” Homepage | UN Global Compact, www.unglobalcompact.org/ Accessed 25 Apr. 2023.

- See 2.

- See 2.

- See 5.

- See 2.

- European Council of the European Union. (n.d.). Paris agreement on climate change. Coliseum. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/climate-change/paris-agreement/ Accessed 14 Sep. 2023.

- “Corporate Disclosure of Climate-Related Information.” Finance, 26 June 2017, www.finance.ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance/disclosures/corporate-disclosure-climate-related-information_en.

- See 16.

- “Example Disclosures.” Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures, www.fsb-tcfd.org/example-disclosures/ Accessed 20 June 2023.

- See 18.

- Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures, www.fsb-tcfd.org/ . Accessed 25 May 2023.

- “Press Release.” SEC, 21 Mar. 2022, www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2022-46.

- “SEC chair Gensler declines to give timeline for final Climate disclosure rule.” The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/sec-chair-gensler-declines-to-give-timeline-for-final-climate-disclosure-rule-bd7028e0 Accessed 14 Sep. 2023.

- Janelle, Knox-Hayes, and Levy David. “The Political Economy of Governance by Disclosure: Carbon Disclosure and Nonfinancial Reporting as Contested Fields of Governance.” Transparency in Global Environmental Governance, 2014, pp. 205–224. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, Rory, and Andy Gouldson. “Does Voluntary Carbon Reporting Meet Investors’ Needs?” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 36, 2012, pp. 60–67. [CrossRef]

- Varnäs et al. (2009), “Environmental consideration in procurement ofconstruction contracts: current practice, problems and opportunities in green procurement in theSwedish construction industry”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 17, pp. 1214-1222 (20) (PDF) Evaluation framework for green procurement in road construction. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280185023_Evaluation_framework_for_green_procurement_in_road_construction [accessed Sep 15 2023].

- “CDP Homepage.” CDP, www.cdp.net/en. Accessed 25 Apr. 2023.

- See 26.

- See 10.

- See 10.

- See 10.

- See 5.

- See 5.

- See 5.

- See 5.

- Nicolo, Giuseppe, et al. “Worldwide Evidence of Corporate Governance Influence on ESG Disclosure in the Utilities Sector.” Utilities Policy, vol. 82, 2023, p. 101549. [CrossRef]

- Global Sustainability Standards Board. GRI - Global Sustainability Standards Board. (n.d.). https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/global-sustainability-standards-board/ Accessed 2 Aug. 2023.

- “GRI 305: Emissions 2016 - Global Reporting Initiative.” GRI Standards GRI 305: EMISSIONS 2016, www.globalreporting.org/standards/media/1012/gri-305-emissions-2016.pdf. Accessed 26 Apr. 2023.

- See 37.

- “Linking GRI Reporting to Other Requirements.” GRI - Global Alignment, www.globalreporting.org/how-to-use-the-gri-standards/global-alignment/. Accessed 2 Aug. 2023.

- “Four Popular ESG Reporting Schemes That Complement Each Other.” Four Popular ESG Reporting Schemes That Complement Each Other, 3 Mar. 2023, www.novisto.com/four-popular-esg-reporting-schemes-that-complement-each-other/#:~:text=GRI%20is%20complementary%20to%20TCFD,GRI%2C%20SASB%2C%20and%20TCFD.

- “Home.” Climate-Related Disclosures, www.ifrs.org/projects/work-plan/climate-related-disclosures/. Accessed 26 Apr. 2023.

- “Home.” IFRS. (n.d.). https://www.ifrs.org/groups/international-sustainability-standards-board/issb-frequently-asked-questions/ Accessed 15 Jul. 2023.

- IFRS. (n.d.-b). Home. IFRS. https://www.ifrs.org/projects/completed-projects/2023/climate-related-disclosures/#about Accessed 15 Sep. 2023.

- Tauringana, V., & Chithambo, L. (2015). The Effect of DEFRA Guidance on Greenhouse Gas Disclosure. British Accounting Review, 47, 425-444. [CrossRef]

- Giannarakis, G., Zafeiriou, E., & Sariannidis, N. (2017). The impact of carbon performance on Climate change disclosure. Business Strategy and the Environment, 26(8), 1078–1094. [CrossRef]

- Escobar MP, Demeritt D. 2017. Paperwork and the decoupling of audit and animal welfare: the challenges of materiality for better regulation. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 35: 169–190.

- García-Sánchez, Isabel-María, and Ligia Noguera-Gámez. “Integrated Reporting and Stakeholder Engagement: The Effect on Information Asymmetry.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, vol. 24, no. 5, 2017, pp. 395–413. [CrossRef]

- Wahl, Annika, et al. “Voluntary Adopters of Integrated Reporting – Evidence on Forecast Accuracy and Firm Value.” Business Strategy and the Environment, vol. 29, no. 6, 2020, pp. 2542–2556. [CrossRef]

- Argento, Daniela, et al. “Sustainability Disclosures of Hybrid Organizations: Swedish State-Owned Enterprises.” Meditari Accountancy Research, vol. 27, no. 4, 2019, pp. 505–533. [CrossRef]

- Andrades, Javier, et al. “Determinants of Information Disclosure by Spanish State-Owned Enterprises in Accordance with Legal Requirements.” International Journal of Public Sector Management, vol. 32, no. 6, 2019, pp. 616–634. [CrossRef]

- See 35.

- Jensen, Michael C., and William H. Meckling. “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure.” Journal of Financial Economics, vol. 3, no. 4, 1976, pp. 305–360. [CrossRef]

- Fama, Eugene F., and Michael C. Jensen. “Separation of Ownership and Control.” The Journal of Law and Economics, vol. 26, no. 2, 1983, pp. 301–325. [CrossRef]

- Barako, Dulacha G., et al. “Factors Influencing Voluntary Corporate Disclosure by Kenyan Companies.” Corporate Governance: An International Review, vol. 14, no. 2, 2006, pp. 107–125. [CrossRef]

- See 52.

- See 54.

- Cerbioni, Fabrizio, and Antonio Parbonetti. “Exploring the Effects of Corporate Governance on Intellectual Capital Disclosure: An Analysis of European Biotechnology Companies.” European Accounting Review, vol. 16, no. 4, 2007, pp. 791–826. [CrossRef]

- Demartini, Chiara, and Sara Trucco. “Relationship between Integrated Reporting and Audit Risk in the European Setting: The Empirical Results.” Integrated Reporting and Audit Quality, 2017, pp. 83–116. [CrossRef]

- Nicolò, Giuseppe, et al. “Sustainable Corporate Governance and Non-Financial Disclosure in Europe: Does the Gender Diversity Matter?” Journal of Applied Accounting Research, vol. 23, no. 1, 2021, pp. 227–249. [CrossRef]

- Gerwing, Tobias, et al. “The Role of Sustainable Corporate Governance in Mandatory Sustainability Reporting Quality.” Journal of Business Economics, vol. 92, no. 3, 2022, pp. 517–555. [CrossRef]

- Lang, Mark, and Russell Lundholm. “Cross-Sectional Determinants of Analyst Ratings of Corporate Disclosures.” Journal of Accounting Research, vol. 31, no. 2, 1993, p. 246. [CrossRef]

- Verrecchia, Robert E. “Essays on Disclosure.” Journal of Accounting and Economics, vol. 32, no. 1–3, 2001, pp. 97–180. [CrossRef]

- See 48.

- Kaymak, T., & Bektas, E. (2017). Corporate Social Responsibility and governance: Information disclosure in multinational corporations. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 24(6), 555–569. [CrossRef]

- Jizi, Mohammad Issam, et al. “Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: Evidence from the US Banking Sector.” Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 125, no. 4, 2013, pp. 601–615. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Charles J.P., and Bikki Jaggi. “Association between Independent Non-Executive Directors, Family Control and Financial Disclosures in Hong Kong.” Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, vol. 19, no. 4–5, 2000, pp. 285–310. [CrossRef]

- Deegan, Craig. “Organizational Legitimacy as a Motive for Sustainability Reporting.” Sustainability Accounting and Accountability, 2007, pp. 127–149. [CrossRef]

- Cho, Charles H., and Dennis M. Patten. “The Role of Environmental Disclosures as Tools of Legitimacy: A Research Note.” Accounting, Organizations and Society, vol. 32, no. 7–8, 2007, pp. 639–647. [CrossRef]

- Shocker, Allan D., and S. Prakash Sethi. “An Approach to Incorporating Societal Preferences in Developing Corporate Action Strategies.” California Management Review, vol. 15, no. 4, 1973, pp. 97–105. [CrossRef]

- Deegan, Craig, and Michaela Rankin. “The Materiality of Environmental Information to Users of Annual Reports.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, vol. 10, no. 4, 1997, pp. 562–583. [CrossRef]

- Suchman, Mark C. “Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches.” The Academy of Management Review, vol. 20, no. 3, 1995, p. 571. [CrossRef]

- Archel, P, and F Lizarraga. “Algunos Determinantes de La Información Medioambiental Divulgada Por Las Empresas Españolas Cotizadas.” Revista de Contabilidad, vol. 4, no. 7, 2001, pp. 129–153.

- Cho, Charles H., et al. “CSR Disclosure: The More Things Change…?” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, vol. 28, no. 1, 2015, pp. 14–35. [CrossRef]

- Patten, D. M. (2002). The relation between Environmental Performance and Environmental Disclosure: A research note. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 27(8), 763–773. [CrossRef]

- Hummel, Katrin, and Christian Schlick. “The Relationship between Sustainability Performance and Sustainability Disclosure – Reconciling Voluntary Disclosure Theory and Legitimacy Theory.” Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, vol. 35, no. 5, 2016, pp. 455–476. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Qingliang. “Institutional Influence, Transition Management and the Demand for Carbon Auditing: The Chinese Experience.” Australian Accounting Review, vol. 29, no. 2, 2018, pp. 376–394. [CrossRef]

- Datt, Rina, et al. “Corporate Choice of Providers of Voluntary Carbon Assurance.” International Journal of Auditing, vol. 24, no. 1, 2020, pp. 145–162. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Le, and Qingliang Tang. “Does Voluntary Carbon Disclosure Reflect Underlying Carbon Performance?” Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics, vol. 10, no. 3, 2014, pp. 191–205. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Le. “The Influence of Institutional Contexts on the Relationship between Voluntary Carbon Disclosure and Carbon Emission Performance.” Accounting & Finance, vol. 59, no. 2, 2017, pp. 1235–1264. [CrossRef]

- Orazalin, Nurlan S., et al. “Board Sustainability Committees, Climate Change Initiatives, Carbon Performance, and Market Value.” British Journal of Management, 2023. [CrossRef]

- See 59.

- Camilleri, Mark Anthony. “Walking the Talk about Corporate Social Responsibility Communication: An Elaboration Likelihood Model Perspective.” Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility, vol. 31, no. 3, 2022, pp. 649–661. [CrossRef]

- Rao, Kathyayini, and Carol Tilt. “Board Diversity and CSR Reporting: An Australian Study.” Meditari Accountancy Research, vol. 24, no. 2, 2016, pp. 182–210. [CrossRef]

- Chan, MuiChing Carina, et al. “Corporate Governance Quality and CSR Disclosures.” Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 125, no. 1, 2013, pp. 59–73. [CrossRef]

- See 35.

- Velte, Patrick. “Does Sustainable Board Governance Drive Corporate Social Responsibility? A Structured Literature Review on European Archival Research.” Journal of Global Responsibility, vol. 14, no. 1, 2022, pp. 46–88. [CrossRef]

- See 84.

- See 86.

- Clarkson, Peter M., et al. “Revisiting the Relation between Environmental Performance and Environmental Disclosure: An Empirical Analysis.” Accounting, Organizations and Society, vol. 33, no. 4–5, 2008, pp. 303–327. [CrossRef]

- Hummel, Katrin, and Christian Schlick. “The Relationship between Sustainability Performance and Sustainability Disclosure – Reconciling Voluntary Disclosure Theory and Legitimacy Theory.” Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, vol. 35, no. 5, 2016, pp. 455–476. [CrossRef]

- See 90.

- Lemma, Tesfaye T., et al. “Corporate Carbon Risk, Voluntary Disclosure, and Cost of Capital: South African Evidence.” Business Strategy and the Environment, vol. 28, no. 1, 2018, pp. 111–126. [CrossRef]

- Spence, Michael. “Job Market Signaling.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 87, no. 3, 1973, p. 355. [CrossRef]

- Bliege Bird, Rebecca, and Eric Alden Smith. “Signaling Theory, Strategic Interaction, and Symbolic Capital.” Current Anthropology, vol. 46, no. 2, 2005, pp. 221–248. [CrossRef]

- Connelly, Brian L., et al. “Signaling Theory: A Review and Assessment.” Journal of Management, vol. 37, no. 1, 2010, pp. 39–67. [CrossRef]

- See 48.

- Freeman, R. E. 1984. Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Boston:Pitman.

- Roberts, Lee, et al. “Investigating Biodiversity and Circular Economy Disclosure Practices: Insights from Global Firms.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, vol. 30, no. 3, 2022, pp. 1053–1069. [CrossRef]

- Perkins, Jon, et al. “Cultural Influences on the Quality of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosures: An Examination of Carbon Disclosure.” Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, vol. 13, no. 5, 2022, pp. 1169–1200. [CrossRef]

- Van der Laan Smith, Joyce, et al. “Exploring Differences in Social Disclosures Internationally: A Stakeholder Perspective.” Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, vol. 24, no. 2, 2005, pp. 123–151. [CrossRef]

- Deegan, Craig & Michaela Rankin, 1997. "The materiality of environmental information to users of annual reports," Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, vol. 10(4), pages 562-583, October.

- Al-Shaer, Habiba, and Mahbub Zaman. “Board Gender Diversity and Sustainability Reporting Quality.” Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics, vol. 12, no. 3, 2016, pp. 210–222. [CrossRef]

- Salvioni, Daniela M., and Francesca Gennari. “Stakeholder Perspective of Corporate Governance and CSR Committees.” Symphonya. Emerging Issues in Management, no. 1, 2019, pp. 28–39. [CrossRef]

- See 77.

- Luo, Le, and Qingliang Tang. “The Real Effects of ESG Reporting and GRI Standards on Carbon Mitigation: International Evidence.” Business Strategy and the Environment, 2022. [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, Paul J., and Walter W. Powell. “The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields.” American Sociological Review, vol. 48, no. 2, 1983, p. 147. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, John L. “Why Would Corporations Behave in Socially Responsible Ways? An Institutional Theory of Corporate Social Responsibility.” Academy of Management Review, vol. 32, no. 3, 2007, pp. 946–967. [CrossRef]

- Godefroit-Winkel, Delphine. “An Institutional Perspective on Climate Change, Markets, and Consumption across Three Countries.” Markets, Globalization & Development Review, vol. 7, no. 4, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Gray, Rob, Mohammed Javad, et al. “Social and Environmental Disclosure and Corporate Characteristics: A Research Note and Extension.” Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, vol. 28, no. 3–4, 2001, pp. 327–356. [CrossRef]

- Adams, Carol A. “Internal Organisational Factors Influencing Corporate Social and Ethical Reporting.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, vol. 15, no. 2, 2002, pp. 223–250. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Tanya M., and Paul D. Hutchison. “The Decision to Disclose Environmental Information: A Research Review and Agenda.” Advances in Accounting, vol. 21, 2005, pp. 83–111. [CrossRef]

- See 99.

- See 100.

- Hulme, Mike. Why We Disagree about Climate Change, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Hulme, M. Climate Change. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2022.

- Tjernström, E., and T. Tietenberg. “Do Differences in Attitudes Explain Differences in National Climate Change Policies?” Ecological Economics, vol. 65, no. 2, 2008, pp. 315–324. [CrossRef]

- Pohjolainen, Pasi, et al. “The Role of National Affluence, Carbon Emissions, and Democracy in Europeans’ Climate Perceptions.” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 2021, pp. 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Salancik, Gerald R., and Jeffrey Pfeffer. “A Social Information Processing Approach to Job Attitudes and Task Design.” Administrative Science Quarterly, vol. 23, no. 2, 1978, p. 224. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Amar, Walid, et al. “Board Gender Diversity and Corporate Response to Sustainability Initiatives: Evidence from the Carbon Disclosure Project.” Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 142, no. 2, 2015, pp. 369–383. [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, Charl, et al. “The Effect of Board Characteristics on Firm Environmental Performance.” Journal of Management, vol. 37, no. 6, 2011, pp. 1636–1663. [CrossRef]

- Haque, Faizul. “The Effects of Board Characteristics and Sustainable Compensation Policy on Carbon Performance of UK Firms.” The British Accounting Review, vol. 49, no. 3, 2017, pp. 347–364. [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, Isabel-María, et al. “Climate Change Innovation: Does Board Gender Diversity Matter?” Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, vol. 8, no. 3, 2023, p. 100372. [CrossRef]

- Caby, Jérôme, et al. “The Effect of Top Management Team Gender Diversity on Climate Change Management: An International Study.” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 2, 2022, p. 1032. [CrossRef]

- Haque, Faizul, and Michael John Jones. “European Firms’ Corporate Biodiversity Disclosures and Board Gender Diversity from 2002 to 2016.” The British Accounting Review, vol. 52, no. 2, 2020, p. 100893. [CrossRef]

- Konadu, Renata, et al. “Board Gender Diversity, Environmental Innovation and Corporate Carbon Emissions.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change, vol. 174, 2022, p. 121279. [CrossRef]

- He, Xiaoping, and Shuo Jiang. “Does Gender Diversity Matter for Green Innovation?” Business Strategy and the Environment, vol. 28, no. 7, 2019, pp. 1341–1356. [CrossRef]

- Hollindale, Janice, et al. “Women on Boards and Greenhouse Gas Emission Disclosures.” Accounting & Finance, vol. 59, no. 1, 2017, pp. 277–308. [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, Muhammad, et al. “Are Women Eco-friendly? Board Gender Diversity and Environmental Innovation.” Business Strategy and the Environment, vol. 29, no. 8, 2020, pp. 3146–3161. [CrossRef]

- Geert Hofstede: Cultural Diversity. Institute of Management Foundation, 1998.

- Eagly, Alice H., et al. “Transformational, Transactional, and Laissez-Faire Leadership Styles: A Meta-Analysis Comparing Women and Men.” Psychological Bulletin, vol. 129, no. 4, 2003, pp. 569–591. [CrossRef]

- See 125.

- Moreno-Ureba, Elena, et al. “An Analysis of the Influence of Female Directors on Environmental Innovation: When Are Women Greener?” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 374, 2022, p. 133871. [CrossRef]

- See 119.

- See 123.

- See 132.

- Atif, Muhammad, et al. “Does Board Gender Diversity Affect Renewable Energy Consumption?” Journal of Corporate Finance, vol. 66, 2021, p. 101665. [CrossRef]

- Gull, Ammar Ali, et al. “Board Gender Composition and Waste Management: Cross-Country Evidence.” The British Accounting Review, vol. 55, no. 1, 2023, p. 101097. [CrossRef]

- See 128.

- Issa, Ayman, and Nasrine Bensalem. “Are Gender-diverse Boards Eco-innovative? The Mediating Role of Corporate Social Responsibility Strategy.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, vol. 30, no. 2, 2022, pp. 742–754. [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, Donald C., and Phyllis A. Mason. “Upper Echelons: The Organization as a Reflection of Its Top Managers.” Academy of Management Review, vol. 9, no. 2, 1984, pp. 193–206. [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, Tasawar. “How Much Does the Board Composition Matter? The Impact of Board Gender Diversity on CEO Compensation.” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 18, 2022, p. 11719. [CrossRef]

- See 125.

- Galia, Fabrice, et al. “Board Composition and Environmental Innovation: Does Gender Diversity Matter?” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, vol. 24, no. 1, 2015, p. 117. [CrossRef]

- Horbach, Jens, and Jojo Jacob. “The Relevance of Personal Characteristics and Gender Diversity for (Eco-)Innovation Activities at the Firm-Level: Results from a Linked Employer-Employee Database in Germany.” Business Strategy and the Environment, vol. 27, no. 7, 2018, pp. 924–934. [CrossRef]

- See 125.

- Logue, D. M. (2020). Theories of social innovation. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- See 146.

- Cowen, Scott S., et al. “The Impact of Corporate Characteristics on Social Responsibility Disclosure: A Typology and Frequency-Based Analysis.” Accounting, Organizations and Society, vol. 12, no. 2, 1987, pp. 111–122. [CrossRef]

- See 49.

- Kuo, Lopin, et al. “Mandatory CSR Disclosure, CSR Assurance, and the Cost of Debt Capital: Evidence from Taiwan.” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 4, 2021, p. 1768. [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, James, et al. “Disclosure Media for Social and Environmental Matters within the Australian Food and Beverage Industry.” Social and Environmental Accountability Journal, vol. 28, no. 1, 2008, pp. 33–44. [CrossRef]

- Hackston, David, and Markus J. Milne. “Some Determinants of Social and Environmental Disclosures in New Zealand Companies.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, vol. 9, no. 1, 1996, pp. 77–108. [CrossRef]

- See 49.

- See 47.

- Cho, Charles H., et al. “CSR Disclosure: The More Things Change…?” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, vol. 28, no. 1, 2015, pp. 14–35. [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, Charl, and Chris Van Staden. “New Zealand Shareholder Attitudes towards Corporate Environmental Disclosure.” Pacific Accounting Review, vol. 24, no. 2, 2012, pp. 186–210. [CrossRef]

- De Klerk, Marna, et al. “The Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure on Share Prices.” Pacific Accounting Review, vol. 27, no. 2, 2015, pp. 208–228. [CrossRef]

- Gray, Rob et al. “Corporate Social and Environmental Reporting.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, vol. 8, no. 2, 1995, pp. 47–77. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Susan B, et al. “Corporate Environmental Disclosures: Are They Useful in Determining Environmental Performance?” Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, vol. 20, no. 3, 2001, pp. 217–240. [CrossRef]

- Wilmshurst, Trevor D., and Geoffrey R. Frost. “Corporate Environmental Reporting.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, vol. 13, no. 1, 2000, pp. 10–26. [CrossRef]

- See 152.

- Gray, Rob, et al. “Social and Environmental Disclosure and Corporate Characteristics: A Research Note and Extension.” Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, vol. 28, no. 3–4, 2001, pp. 327–356. [CrossRef]

- Holder-Webb, Lori, et al. “The Supply of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosures among U.S. Firms.” Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 84, no. 4, 2008, pp. 497–527. [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, Isabel-María, et al. “Climate Change Innovation: Does Board Gender Diversity Matter?” Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, vol. 8, no. 3, 2023, p. 100372. [CrossRef]

- Michelon, Giovanna, and Antonio Parbonetti. “The Effect of Corporate Governance on Sustainability Disclosure.” Journal of Management & Governance, vol. 16, no. 3, 2010, pp. 477–509. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Lin, et al. “Gender Diversity, Board Independence, Environmental Committee and Greenhouse Gas Disclosure.” The British Accounting Review, vol. 47, no. 4, 2015, pp. 409–424. [CrossRef]

- See 77.

- Hsiao, Pei-Chi Kelly, et al. “Is Voluntary International Integrated Reporting Framework Adoption A Step on the Sustainability Road and Does Adoption Matter to Capital Markets?” Meditari Accountancy Research, vol. 30, no. 3, 2021, pp. 786–818. [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, Charl. “Stakeholder Requirements for Sustainability Reporting.” Sustainability Accounting and Integrated Reporting, 2017, pp. 57–63. [CrossRef]

- Traxler, A. A., & Greiling, D. (2018). Sustainable public value reporting of electric utilities. Baltic Journal of Management, 14(1), 103–121. [CrossRef]

- See 50.

- See 35.

- Carter, David A., et al. “Corporate Governance, Board Diversity, and Firm Value.” The Financial Review, vol. 38, no. 1, 2003, pp. 33–53. [CrossRef]

- See 166.

- See 83.

- See 166.

- Pucheta-Martínez, María Consuelo, and Isabel Gallego-Álvarez. “Do Board Characteristics Drive Firm Performance? An International Perspective.” Review of Managerial Science, vol. 14, no. 6, 2019, pp. 1251–1297. [CrossRef]

- See 173.

- Jizi, Mohammad. “The Influence of Board Composition on Sustainable Development Disclosure.” Business Strategy and the Environment, vol. 26, no. 5, 2017, pp. 640–655. [CrossRef]

- Srinidhi, Bin, et al. “How Do Female Directors Improve Board Governance? A Mechanism Based on Norm Changes.” Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics, vol. 16, no. 1, 2020, p. 100181. [CrossRef]

- Seebeck, Andreas, and Julia Vetter. “Not Just a Gender Numbers Game: How Board Gender Diversity Affects Corporate Risk Disclosure.” Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 177, no. 2, 2021, pp. 395–420. [CrossRef]

- Rose, Caspar. “Does Female Board Representation Influence Firm Performance? The Danish Evidence.” Corporate Governance: An International Review, vol. 15, no. 2, 2007, pp. 404–413. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Fuxiu, et al. “Female Board Chairpersons, Firm Performance, and Corporate Governance: Evidence from China.” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Le Loarne - Lemaire, S., G. Brush, C., Calabrò, A., & Maâlaoui, A. (2022). Introduction to women, family and family businesses across entrepreneurial contexts. Women, Family and Family Businesses Across Entrepreneurial Contexts, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Akca, Meltem, and Burcu Özge Çalışkan. “Gender Diversity in Board of Directors.” Gender and Diversity, pp. 493–507. [CrossRef]

- See 143.

- See 139.

- See 128.

- Naveed, Khwaja, et al. “Board Gender Diversity and Corporate Green Innovation: An Industry-level Institutional Perspective.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, vol. 30, no. 2, 2022, pp. 755–772. [CrossRef]

- See 173.

- Prado-Lorenzo, Jose-Manuel, and Isabel-Maria Garcia-Sanchez. “The Role of the Board of Directors in Disseminating Relevant Information on Greenhouse Gases.” Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 97, no. 3, 2010, pp. 391–424. [CrossRef]

- See 166.

- See 35.

- Lu, Jing, and Irene M. Herremans. “Board Gender Diversity and Environmental Performance: An Industries Perspective.” Business Strategy and the Environment, vol. 28, no. 7, 2019, pp. 1449–1464. [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, Paul B., et al. “The Role of Board Gender and Foreign Ownership in the CSR Performance of Chinese Listed Firms.” Journal of Corporate Finance, vol. 42, 2017, pp. 75–99. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Xin, et al. “Are Firms with State Ownership Greener? An Institutional Complexity View.” Business Strategy and the Environment, vol. 29, no. 1, 2019, pp. 197–211. [CrossRef]

- See 121.

- See 126.

- See 166.

- See 128.

- See 196.

- Post, Corinne, and Kris Byron. “Women on Boards and Firm Financial Performance: A Meta-Analysis.” Academy of Management Journal, vol. 58, no. 5, 2015, pp. 1546–1571. [CrossRef]

- See 86.

- See 166.

- Frias-Aceituno, José V., et al. “Explanatory Factors of Integrated Sustainability and Financial Reporting.” Business Strategy and the Environment, vol. 23, no. 1, 2012, pp. 56–72. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Feijoo, Belen, et al. “Women on Boards: Do They Affect Sustainability Reporting?” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, vol. 21, no. 6, 2013, pp. 351–364. [CrossRef]

- See 83.

- See 54.

- See 65.

- Se 177.

- Erin, Olayinka, et al. “Corporate Governance and Sustainability Reporting Quality: Evidence from Nigeria.” Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, vol. 13, no. 3, 2021, pp. 680–707. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, Kathy, and Gary O’Donovan. “Corporate Governance and Environmental Reporting: An Australian Study.” Corporate Governance: An International Review, vol. 15, no. 5, 2007, pp. 944–956. [CrossRef]

- See 83.

- Arayssi, Mahmoud, et al. “The Impact of Board Composition on the Level of ESG Disclosures in GCC Countries.” Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, vol. 11, no. 1, 2020, pp. 137–161. [CrossRef]

- See 35.

- See 119.

- Ararat, Melsa, and Borhan Sayedy. “Gender and Climate Change Disclosure: An Interdimensional Policy Approach.” Sustainability, vol. 11, no. 24, 2019, p. 7217. [CrossRef]

- See 166.

- Tingbani, Ishmael, et al. “Board Gender Diversity, Environmental Committee and Greenhouse Gas Voluntary Disclosures.” Business Strategy and the Environment, vol. 29, no. 6, 2020, pp. 2194–2210. [CrossRef]

- Gonenc, Halit, and Antonina V. Krasnikova. “Board Gender Diversity and Voluntary Carbon Emission Disclosure.” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 21, 2022, p. 14418. [CrossRef]

- See 143.

- Glass, C., Cook, A., & Ingersoll, A. R. (2015). Do women leaders promote sustainability? analyzing the effect of corporate governance composition on environmental performance. Business Strategy and the Environment, 25(7), 495–511. [CrossRef]

- 223. See 144.

- 224. See 126.

- 225. See 166.

- 226. See 132.

- See 128.

- See 189.

- See 136.

- See 137.

- See 164.

- See 121.

- García Martín, C. José, and Begoña Herrero. “Do Board Characteristics Affect Environmental Performance? A Study of EU Firms.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, vol. 27, no. 1, 2019, pp. 74–94. [CrossRef]

- See 125.

- See 35.

- See 177.

- See 60.

- See 77.

- Chen, Jennifer C., and Robin W. Roberts. “Toward a More Coherent Understanding of the Organization–Society Relationship: A Theoretical Consideration for Social and Environmental Accounting Research.” Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 97, no. 4, 2010, pp. 651–665. [CrossRef]

- Helfaya, Akrum, and Tantawy Moussa. “Do Board’s Corporate Social Responsibility Strategy and Orientation Influence Environmental Sustainability Disclosure? UK Evidence.” Business Strategy and the Environment, vol. 26, no. 8, 2017, pp. 1061–1077. [CrossRef]

- Peters, Gary F., and Andrea M. Romi. “The Association between Sustainability Governance Characteristics and the Assurance of Corporate Sustainability Reports.” AUDITING: A Journal of Practice & Theory, vol. 34, no. 1, 2014, pp. 163–198. [CrossRef]

- See 166.

- See 165.

- See 165.

- See 166.

- See 165.

- Amran, Azlan, et al. “The Influence of Governance Structure and Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility toward Sustainability Reporting Quality.” Business Strategy and the Environment, vol. 23, no. 4, 2013, pp. 217–235. [CrossRef]

- See 177.

- See 60.

- See 166.

- Cucari, Nicola, et al. “Diversity of Board of Directors and Environmental Social Governance: Evidence from Italian Listed Companies.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, vol. 25, no. 3, 2017, pp. 250–266. [CrossRef]

- See 215.

- See 35.

- See 121.

- Cordova, Carmen, et al. “Contextual and Corporate Governance Effects on Carbon Accounting and Carbon Performance in Emerging Economies.” Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, vol. 21, no. 3, 2021, pp. 536–550. [CrossRef]

- Saha, Raiswa, et al. “Effect of Ethical Leadership and Corporate Social Responsibility on Firm Performance: A Systematic Review.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, vol. 27, no. 2, 2019, pp. 409–429. [CrossRef]

- Kujala, Johanna, et al. “Stakeholder Engagement: Past, Present, and Future.” Business & Society, vol. 61, no. 5, 2022, pp. 1136–1196. [CrossRef]

- Peters, Gary F., et al. “The Influence of Corporate Sustainability Officers on Performance.” Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 159, no. 4, 2018, pp. 1065–1087. [CrossRef]

- Serafeim, George. “Public Sentiment and the Price of Corporate Sustainability.” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Perkins, Kathleen Miller, and George Serafeim. “Chief Sustainability Officers.” Leading Sustainable Change, 2015, pp. 196–221. [CrossRef]

- See 258.

- The global leader for impact reporting. GRI - Home. (n.d.). https://www.globalreporting.org/. Accessed June 22, 2023.

- See 36.

- Willis, Alan C.A. “The Role of the Global Reporting Initiative’s Sustainability Reporting Guidelines in the Social Screening of Investments.” Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 43, no. 3, 2003, pp. 233–237.

- Milne, Markus J., and Rob Gray. “W(H)Ither Ecology? The Triple Bottom Line, the Global Reporting Initiative, and Corporate Sustainability Reporting.” Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 118, no. 1, 2012, pp. 13–29. [CrossRef]

- See 105.

- Adams, Carol A. “The Ethical, Social and Environmental Reporting-performance Portrayal Gap.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, vol. 17, no. 5, 2004, pp. 731–757. [CrossRef]

- See 195.

- DJSI Index family. S&P Global Homepage. (n.d.). https://www.spglobal.com/esg/performance/indices/djsi-index-family, accessed 24 Apr 2022.

- López, M. Victoria, et al. “Sustainable Development and Corporate Performance: A Study Based on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index.” Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 75, no. 3, 2007, pp. 285–300. [CrossRef]

- Lorne, F. T., & Dilling, P. (2012). Creating values for sustainability: Stakeholders engagement, incentive alignment, and value currency. Economics Research International, 2012, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- See 269.

- See 269.

- Cordeiro, James J., and Manish Tewari. “Firm Characteristics, Industry Context, and Investor Reactions to Environmental CSR: A Stakeholder Theory Approach.” Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 130, no. 4, 2014, pp. 833–849. [CrossRef]

- See 155.

- See 156.

- See 157.

- See 159.

- Biktimirov, Ernest N., and Yuanbin Xu. “Market Reactions to Changes in the Dow Jones Industrial Average Index.” International Journal of Managerial Finance, vol. 15, no. 5, 2019, pp. 792–812. [CrossRef]

- See 160.

- See 90.

- Searcy, Cory, and Doaa Elkhawas. “Corporate Sustainability Ratings: An Investigation into How Corporations Use the Dow Jones Sustainability Index.” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 35, 2012, pp. 79–92. [CrossRef]

- Drempetic, Samuel, et al. “The Influence of Firm Size on the ESG Score: Corporate Sustainability Ratings under Review.” Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 167, no. 2, 2019, pp. 333–360. [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, Dan, et al. “Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure and the Cost of Equity Capital: The Roles of Stakeholder Orientation and Financial Transparency.” Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, vol. 33, no. 4, 2014, pp. 328–355. [CrossRef]

- See 105.

- See 105.

- Jiang, Yan, et al. “The Value Relevance of Corporate Voluntary Carbon Disclosure: Evidence from the United States and BRIC Countries.” Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics, vol. 17, no. 3, 2021, p. 100279. [CrossRef]

- See 89.

- Erhart, Szilárd. “Take It with a Pinch of Salt—ESG Rating of Stocks and Stock Indices.” International Review of Financial Analysis, vol. 83, 2022, p. 102308. [CrossRef]

- “ESG Ratings & Climate Search Tool.” MSCI, www.msci.com/our-solutions/esg-investing/esg-ratings-climate-search-tool. Accessed 27 May 2023.

- See 289.

- See 10.

- See 10.

- Dilling, P. F. A., & Harris, P. (2018). Reporting on long-term value creation by Canadian companies: A longitudinal assessment. Journal of Cleaner Production, 191, 350–360. [CrossRef]

- Orzes, Guido, et al. “The Impact of the United Nations Global Compact on Firm Performance: A Longitudinal Analysis.” International Journal of Production Economics, vol. 227, 2020, p. 107664. [CrossRef]

- Msiska, Moses, et al. “Correction: Doing Well by Doing Good with the Performance of United Nations Global Compact Climate Change Champions.” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, vol. 9, no. 1, 2022. [CrossRef]

- See 10.

- See 10.

- See 295.

- Hayward, Rob, et al. “The UN Global Compact-Accenture CEO Study on Sustainability 2013.” UN Global Compact Reports, vol. 5, no. 3, 2013, pp. 1–60. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Hau L., and Christopher S. Tang. “Socially and Environmentally Responsible Value Chain Innovations: New Operations Management Research Opportunities.” Management Science, vol. 64, no. 3, 2018, pp. 983–996. [CrossRef]

- Janney, Jay J., et al. “Glass Houses? Market Reactions to Firms Joining the UN Global Compact.” Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 90, no. 3, 2009, pp. 407–423. [CrossRef]

- See 77.

- Stoddard, Isak, et al. “Three Decades of Climate Mitigation: Why Haven’t We Bent the Global Emissions Curve?” Annual Review of Environment and Resources, vol. 46, no. 1, 2021, pp. 653–689. [CrossRef]

- See 105.

- See 77.

- See 105.

- See 20.

- Kuo, Lopin, and Bao-Guang Chang. “The Affecting Factors of Circular Economy Information and Its Impact on Corporate Economic Sustainability-Evidence from China.” Sustainable Production and Consumption, vol. 27, 2021, pp. 986–997. [CrossRef]

- See 122.

- See 98.

- See 35.

- Bahari, N.A.S., Alrazi, B., Husin, N.M., 2016. A comparative analysis of carbon reporting by electricity generating companies in China, India, and Japan. Procedia Econ.Finance 35, 74–81. [CrossRef]

- Talbot, D., Boiral, O. GHG Reporting and Impression Management: An Assessment of Sustainability Reports from the Energy Sector. J Bus Ethics 147, 367–383 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, Ella Mae, et al. “Firm-Value Effects of Carbon Emissions and Carbon Disclosures.” The Accounting Review, vol. 89, no. 2, 2013, pp. 695–724. [CrossRef]

- See 99.

- Eccles, Robert, et al. The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance, 2012. [CrossRef]

- See 20.

- See 20.

- Consultation Draft toward Common Metrics and ... - World Economic Forum, 2020, www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_IBC_ESG_Metrics_Discussion_Paper.pdf.

- O’Dwyer, Brendan, and Jeffrey Unerman. “Shifting the Focus of Sustainability Accounting from Impacts to Risks and Dependencies: RESEARCHING THE TRANSFORMATIVE POTENTIAL OF TCFD Reporting.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, vol. 33, no. 5, 2020, pp. 1113–1141. [CrossRef]

- See 20.

- See 20.

- Eccles, Robert G., and Michael P. Krzus. “Implementing the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures Recommendations: An Assessment of Corporate Readiness.” Schmalenbach Business Review, vol. 71, no. 2, 2018, pp. 287–293. [CrossRef]

- Principale, Salvatore, and Simone Pizzi. “The Determinants of TCFD Reporting: A Focus on the Italian Context.” Administrative Sciences, vol. 13, no. 2, 2023, p. 61. [CrossRef]

- Jannik Gerwanski & Othar Kordsachia & Patrick Velte, 2019. "Determinants of materiality disclosure quality in integrated reporting: Empirical evidence from an international setting," Business Strategy and the Environment, Wiley Blackwell, vol. 28(5), pages 750-770, July.

- See 269.

- Hill, Aaron D., et al. “Endogeneity: A Review and Agenda for the Methodology-Practice Divide Affecting Micro and Macro Research.” Journal of Management, vol. 47, no. 1, 2020, pp. 105–143. [CrossRef]

- Rovetta, Alessandro. “Raiders of the Lost Correlation: A Guide on Using Pearson and Spearman Coefficients to Detect Hidden Correlations in Medical Sciences.” Cureus, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Fidell, Linda S., and Barbara G. Tabachnick. “Preparatory Data Analysis.” Handbook of Psychology, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Johnston, Ron, et al. “Confounding and Collinearity in Regression Analysis: A Cautionary Tale and an Alternative Procedure, Illustrated by Studies of British Voting Behaviour.” Quality & Quantity, vol. 52, no. 4, 2017, pp. 1957–1976. [CrossRef]

- See 121.

- Siddique, M. A., Akhtaruzzaman, M., Rashid, A., & Hammami, H. (2021). Carbon disclosure, carbon performance and financial performance: International evidence. International Review of Financial Analysis, 75, 101734.

- See 186.

- “Home.” www.stata.com . Accessed 28 May 2023.

- See 166.

- See 220.

- Peng, Xuhui, et al. “Board Gender Diversity, Corporate Social Disclosures, and National Culture.” SAGE Open, vol. 12, no. 4, 2022, p. 215824402211309. [CrossRef]

- See 220.

- See 191.

- M. Shamil, Mohamed, et al. “The Influence of Board Characteristics on Sustainability Reporting.” Asian Review of Accounting, vol. 22, no. 2, 2014, pp. 78–97. [CrossRef]

- Husted, Bryan W., and José Milton Sousa-Filho. “Board Structure and Environmental, Social, and Governance Disclosure in Latin America.” Journal of Business Research, vol. 102, 2019, pp. 220–227. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).