‡ Shared last authorship.

1. Introduction

More than one third of the adult population of western high-income countries are physically inactive [1–3]. Physical inactivity leads to increased risk of chronic diseases, obesity, and early death [4]. Vice versa, physical activity has proven to prevent chronic diseases and to increase mental health, quality of life, and wellbeing [4-6].

During the last decades, allowing physical exercise training during work, has increased and today, the workplace is considered an ideal arena for implementing physical exercise training [

7,

8]. However, despite promising effects one size usually does not fit all. Recently, an approach with an individualized exercise program has been launched [

9]. Sjøgaard, Justesen, Murray, Dalager and Søgaard [

9] developed the concept ‘Intelligent Physical Exercise Training’ (IPET) which is individualized physical exercise training that consists of 60 minutes weekly moderate to high intensity training tailored to each employee’s work exposure and individual health profile. Dalager, Justesen [10] demonstrated the effectiveness of IPET on aerobic capacity and blood pressure among office workers. Furthermore, IPET has increased workability, productivity, and decreased sickness absenteeism by 29% [

11].

Literature reports that participation in exercise training at workplaces can be challenging. A review of nine Danish randomized controlled trials found that continuous adherence to physical activity at the workplace varied from 31-86% [

12]. Jørgensen, Villadsen [13] examined factors associated with low participation in health-promoting activities at the workplace and found, that high physical and/or psychological demands in the job combined with low job control reduced participation. In an intervention study Ilvig, Bredahl [14] tried to implement IPET at a workplace in a healthcare context and faced challenges also. Female healthcare workers employed in home care and nursing homes reported that reduced flexibility at the workplace, lack of support from management, the content and intensity of the programs, and low coherence between published information and reality on the workplace were barriers for participation. Everyday life in a hospital can be unpredictable and changeable, as demands are constantly placed on the staff from patients and relatives to provide care [

15]. In addition, staffs in Danish hospitals are under a great pressure because of understaffing, and among nurses up to 60% have reported they felt stressed and blamed work as the cause [

16], which could be a barrier to participate in exercise during work. Indeed, nurses have reported high prevalence of musculoskeletal pain, which entails increased risk for long-term sick leave [

17]. Thus, there is a high need to intervene within this profession and other healthcare workers. Exercise during work may be an important intervention here, to enhance the resilience of them and improve their health.

This qualitative study of barriers and facilitators was conducted during a pilot trial of IPET during working hours in a hospital department [

18]. The intervention showed positive changes of objectively and subjectively measured health outcomes, and data on clinical health parameters, well-being, productivity and self-related health from the pilot trail have been published elsewhere [18]. However, the adherence was low, and the dropout rate was highest among nurses and social and healthcare assistants [18]. Even though IPET during work is associated with positive changes in a hospital, more knowledge is needed to identify barriers and facilitators to prevent dropout and low adherence. Thus, the aim of this study was to identify barriers and facilitators for participation in an IPET intervention during working hours.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

The study was a qualitative study, conducted with a sample of employees participating in a pilot trial at Department of Pulmonary and Infectious Disease, Nordsjælland’s Hospital, Denmark, from August to December 2021. Semi-structured interviews were conducted to elucidate the employees' barriers and facilitators.

2.2. Ethics

The informants gave oral and written consent before the interviews. The study complied with The Central Capital Region Committees on Health Research Ethics (H-21038302) and The Data Protection Agency (P-2021-472), and the study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

2.3. The Intervention

A description of the intervention is published elsewhere [18]. In brief, the IPET intervention was free of charge and lasted for 12 weeks. The employees were invited to participate in two weekly training sessions of 30 minutes each during work hours from 7.30 AM to 3.45 PM. The training sessions were performed in groups of maximum 12 participants and consisted of a short warm up, followed by individualized exercises within the training categories of aerobic training resistance training, and balance training. The exercises were individualized to each employee based on a baseline health check (aerobic capacity, blood pressure, musculoskeletal pain), and the employee’s exercise preferences. All exercise sessions were supervised by a professional educated in sport science or physiotherapy.

2.4. Sampling and Recruitment

To elucidate barriers and facilitators, criterion of inclusion was level of participation in the IPET intervention, focusing on employees who 1) did not wish to participate 2) signed up but did not participate 3) signed up but dropped out during the first weeks, 4) participated throughout the intervention. As participation in the intervention varied depending on profession, we sought to recruit both the nursing staff, the administrative staff, as well as from the management level. Recruitment for the interviews was performed by author JBJ and an established contact person at the hospital, who provided a list of employees with profession and degree of participation in the intervention.

2.5. Interview Process

The eight semi-structured interviews were except one, conducted face-to-face with the management, administrative staff, and nursing staff, from December 2021 to April 2022. Thirteen individuals volunteered to participate in the study. The informants were given fictitious names to ensure anonymity. They were interviewed at their workplace in an undisturbed setting and with interview durations of 16-43 min.

A semi-structured interview guide was designed based on existing literature. The interview guide consisted of open-ended questions prepared with supplementing questions for elaboration. Questions were formulated in an everyday language and conduced in Danish, audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim within 24 hours after the interview by author TML or CJP. Informants were ensured complete anonymity.

2.6. Data Analysis

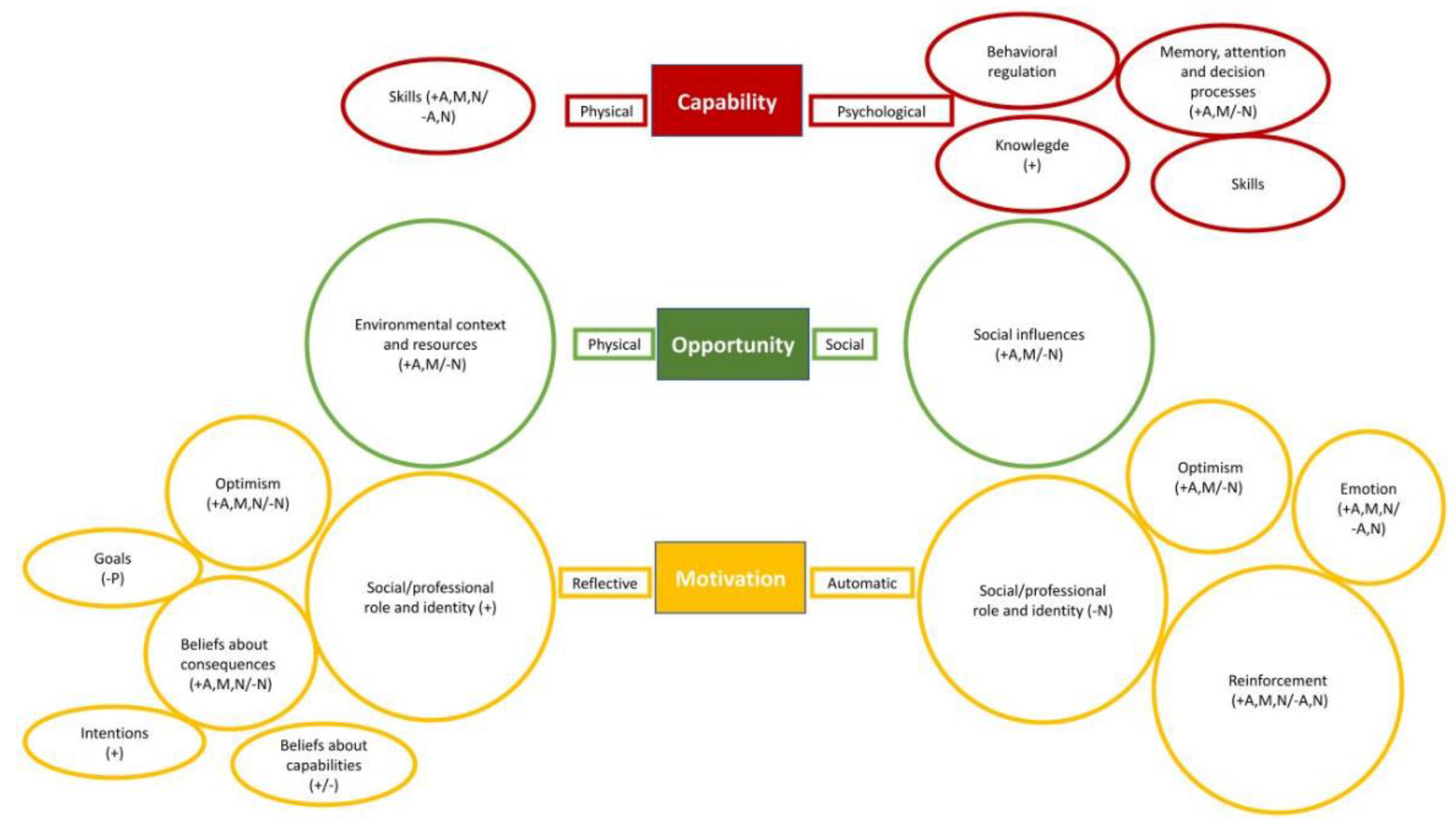

The structure for the analysis was based on a thematical approach containing six iterative phases: 1) familiarization, 2) coding, 3) theme development, 4) refinement 5) naming, and 6) writing up [19]. First, familiarization with the data was achieved by thoroughly reading it and noting the most dominant content. Second, the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) [20] were used to deductive coding of the data and to identify patterns. Third, themes were categorized according to the three factors: capability (physical and psychological), opportunity (social and physical) and motivation (automatic and reflective) from the COM-B model in The Behavioral Change Wheel (BCW) [21].Fourth, the subthemes were identified in relation to specific barriers and facilitators in the context of the hospital. The subthemes were used as a basis for discussing the findings. Fifth, the domains were listed depending on which were most frequent, less frequent, and rare mentioned. Sixth phase consisted of reading and processing the material and writing. Authors CJP and TML drafted first version of the analysis, and JBJ and TD were involved until consensus were reached. The TDF and COM-B were applied to systematize and structure the findings and create recommendations for a more successful future implementation of evidence-based practice [22-24].

3. Results

Table 1 presents the characteristics of informants and interview methods. For level of participation, seven individuals participated in 13 [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24] (median (range)) out of 24 exercise sessions during the intervention period.

Figure 1 presents an overview of the results of the thematic analysis: it represents each TDF-domains’ impact by its size, based on the number of codes given during the analysis within the specific domains. Furthermore, the domains are connected to the COM-B factors.

In general, all informants found the IPET intervention during working hours relevant, and all wanted to participate in future IPET interventions. During the data collection we found different opinions within the staff groups of what was considered crucial for participating in the intervention.

3.1. Capability

3.1.1. Psychological Capability

The most frequent identified barrier in ‘psychological capability’ was the coordination and planning of the training during workdays. The nursing staff experienced difficulties in being able to participate. Initially, they felt motivated to participate, but found it very difficult to join the training because of the workload.

Nina: “(…) I was in favor of it in the beginning too. And I was very much like “come on friends, we'll do it" and "we must all join" and organized one or the other department competition to see who could lose most weight and so on. Umm… But I don't think that I will get them to participate in that again. Haha…” (Interview 7, P22-125, TDF: Behavioral regulation).

Some employees felt that they did not receive information about the intervention became a barrier for participation. In addition, they felt they were a piece of a larger puzzle, and that the purpose of the project was more related to increased productivity and research results than to the wellbeing of the employees.

Allison:“Yes, I felt a bit like I was used as a test animal. I was a part of an initiative to obtain research results.” (Interview 4, P598-599, TDF: Knowledge)

Facilitators regarding the ’psychological capability’ included having a personalized exercise program and being able to coordinate who was exercising in the entire unit. Furthermore, provided information regarding the intervention from the project workers facilitated participation.

3.1.2. Physical Capability

Some participants experienced having their ‘physical capability’ limited by the intervention being too vigorous and provoking previous injuries.

Allison:“It was simply too hard. Because… one would say that with the type of injury I have (...), it is really important for me to have a lot of stability exercises... (...) Even though there were, the exercises were too hard.” (Interview 4, P29- 31, TDF: Skills).

Other participants felt their ‘physical capability’ were improved by the challenging and tailored exercise programs, taking individual needs into consideration.

Amber:"I can also say that..., for example... I've got diagnosed (disease). So, I have simply been pleased by the fact that some people have gone to great lengths to find things for me, and I had special programs tailored for me.” (Interview 3, P111-114, TDF: Skills)

Through the analysis of ‘capability’, two sub-themes related to the context of the hospital department were identified: ‘sharing of knowledge and information’ and ‘involvement’.

3.2. Opportunity

3.2.1. Physical Opportunity

The most frequent barrier in ‘physical opportunity’ was the pressure from busyness in the department. Patients in need for care would always be a priority. While managers and administrative staff were able to coordinate duty schedules and participate in the intervention, the nursing staff often found it difficult to leave the department to take part in the IPET.

Nina:"But it just ended up with you suddenly being responsible for eight patients instead of four or something, right? Because one of your colleagues had to leave. (...) when you then were given the responsibility for someone else’s patients for an hour, during the visitation of these patients, it was difficult to have to follow up on eight patients (…) Those who are not part of the actual staffing and those who are not working in the care departments, they can find time for it and sort of structure it and plan it accordingly." (Interview 7, P23-33, TDF: Environmental context and resources)

Natalie "I also think those who were training (...) were the quality nurse and the intro nurse. It was those people, who don’t have patients or not that many patients... or those with an intern, if you can put it that way.” (Interview 6, P36-38, TDF: Environmental context and resources)

Nick:“And it's still crazy. After all, we work 24/7, 365 days a year. It never stops. It's a crazy workplace in that way." (Interview 4, P344-345, TDF: Environmental context and resources)

The pressure of busyness was also evident when interviewing the employees. We experienced difficulties in setting up meetings with the nursing staff. However, one of the managers suggested that the busyness in the department had more to do with the employees being exhausted after the covid pandemic, than the actual busyness.

Megan: “But what we can see in this hospital is, that it is not busy, we do not have high occupancy, all the beds are not occupied every day. And we have not cut down in staffing, there has not been cutbacks in several years. And the vacant positions they have, has not increased a lot the last couple of years. On the contrary, almost no one has gotten all their staff hired (…) and because it has been busy, and COVID came along, and they are maybe tired. Then that exhaustion, is what we need to talk to them about. And that has something to do with staff management. (Interview 8, P164-170, TDF: Environmental context and resources)

In ‘physical opportunity’ the managers and administrative staff experienced that structuring and planning the workday were facilitators for exercising.

3.2.2. Social Opportunity

In ‘social opportunity’ social pressure was reported as a barrier. The administrative and nursing staff felt they imposed a workload to their co-workers when they left the department to exercise, which resulted in irritation and a negative atmosphere.

Amber:"Yes, because I've actually heard something... someone saying " Well, I can't go train because I have to look after yours. I can't go". It will very quickly create friction.” (Interview 3, P181- 183, TDF: Social influence)

A facilitator for ‘social opportunity’ was a sense of coherence and doing something different, than work with your co-workers, and getting to know co-workers from other departments.

Amber:"The fact that we are a large department, spread over many departments, that you actually also met each other in another setting. So, it benefited both yourself and the group. Someone you might not have seen in months, right? The thing about training together.” (Interview 3, P49-52, TDF: Social influence)

Through the analysis of physical and social opportunity, two sub-themes related to the context of the hospital department were identified: ‘guidance and structure’ and ‘culture’

3.3. Motivation

3.3.1. Reflexive Motivation

Barriers regarding ‘reflexive motivation’ covered not having a promised physical test conducted before the intervention, and little regard or consideration to previous injuries. Furthermore, the nursing staff did not expect the intervention to be realistic to implement during working hours. The nursing staff viewed the intervention as a pr-stunt from a top management, and as a way of doing something good for them as staff, but in a misunderstood way. They felt the purpose was to optimize workflow at the department, by trying to make the staff more productive instead of taking a critical look at workplace conditions and having enough staff at work.

Natalie:"I also think that it is difficult that we now also have to do that. We are constantly pulled into this or that or the other project. And the managers keep saying: "It's a good idea, and we would like to be contributing to that” and good God. But it's just not always that the circumstances or the resources then follow (...). But the time is also not provided, even if it is supported by the section management and department management.” (Interview 6, P255-260, TDF: Social/professional role and identity)

Nicole:"Then you have to go out yourself and make some kind of extra effort, you actually don't want to. So, it just becomes very manipulative in one way or another and it appears as though we have to in order for us to attract new employees and... because we train during working hours. (...) The speed at which articles came out, to tell how crazy good we are here, because the management allows us to train. And then it's all just chaos, and you can't get anyone to take care of your patients and stuff like that.” (Interview 6, P544-549, TDF: Optimism)

The nursing staff found the goals of the intervention too vague, thus, they found it difficult to set their own goals.

Facilitators of the ‘reflexive motivation’ were tailored and individualized exercise training programs together with that the training was prescribed as 2x30 minutes a week, which was a foreseeable period. The managers tried to enhance their staff´s ‘reflexive motivation’ by participating in the intervention themselves.

3.3.2. Automatic Motivation

In ‘automatic motivation’ there was a lack of role models. The project team had planned on educating ‘training ambassadors’ to facilitate the implementation. Some informants pointed out that involving training ambassadors in the implementation process could have increased the staff’s motivation for participating in the training.

Madison:"So maybe they should have been here more. Those who trained (the exercise experts). That is, in the morning and try to get people along or... walk around during the day and talk to people once in a while and drop by a little bit. They dropped by a few times, but it was very little. But stay here a little longer and try to pull people along a bit too, so that they... "give it a go" or "is there something that prevents you?”, “can we try that?”.” (Interview 5, P134-138, TDF: Reinforcement)

The staff groups working in inpatient sections of the departments found it easier to attend training sessions placed in the morning and afternoon rather than the sessions placed midday. Some of the nursing staff found the training dull and monotonous.

Natalie:“(...) And then suddenly these foolish elastic bands turn up. THAT, I don't really get anything out of. (...) And then you get those training programs, which I didn't care for much (...) You came up with some goals for the preliminary conversations. I also felt they were not followed up on" (Interview 6, P111-116, TDF: Reinforcement).

The employees experienced that the managers tried to make it possible for them to leave the department to exercise, but without giving them the right work conditions to do so.

Nicole:"But I also know, from the management. They also frequently tried to state that we should try to let people go down and try because it is important that you participated. But then there was such an obvious irritation... and then again, we also think it is annoying when you get more tasks.” (Interview 6, P73-76, TDF: Emotions)

The intervention’s positive effect on mood, health and work productivity served as a facilitator in ‘automatic motivation’. Furthermore, the exercise experts and settings of the intervention were considered motivational for the management and administrative staff.

Marc:"But among those who are still in, there is some kind of dynamic and joy. There is... you do things, the task in a different way. So, in reality I think, that this is one of the really big benefits. That's the thing about the glass being half full, isn't it. It's not half empty when you sit down.” (Interview 3, P507-510, TDF: Optimism)

Amber:"Well, our manager led by example. And you also trained together with them occasionally, and it was really nice to meet your manager in a different way.” (Interview 3, P546-548, TDF: Social/professional role and identity, Emotions)

Based on the results of the analysis of ‘motivation’ three subthemes were identified: ‘individualization’, ‘purpose and goalsetting’ and ‘incentives’.

Table 2 provides an overview of identified subthemes in relation to TDF-domains and COM-B factors.

4. Discussion

This study identified barriers and facilitators to participate in exercise training during work at a hospital. Barriers included limited structure of the workday which made it difficult to leave the department to exercise, and missing facilitation of participation in the training. Facilitators included IPET creating a feeling of physical and psychological well-being, motivating programs and exercise experts, gaining a sense of community through exercising and the management assisting in coordinating and structuring the workday to make time for participating in IPET.

4.1. Structure and Involvement

Nursing staff, managers and administrative staff emphasized desire to participate in the intervention. However, especially nurses felt incapable of participating due to time pressure and the ongoing workflow. The nurses felt their working schedule, including unpredictable tasks, as a barrier to participate, and they feared compromising patient safety. Kirk, Sivertsen [25] found same challenges during implementation of a screening tool in a Danish acute care unit. Limited resources, including time, led to the staff being afraid of making mistakes and thereby influencing patient safety. Kirk, Sivertsen [25] emphasized the managers’ role as facilitators in case they choose to support the desired change. In this study, nurses wished more involvement and cooperation from the management to create structure in the work to make it possible to leave the department to exercise. A systematic review found that a management could function as a barrier as well as a facilitator during the change process depending on whether they were supportive or absent [26]. To obtain a successful implementation, the management is supposed to endorse the intervention, understand the relevance of it and provide the necessary flexibility during workdays. To support the nursing staff in participating in the intervention, the management might consider assisting them in structuring their workday and be clearly supportive of the desired change.

The managers and administrative staff expressed how clear communication, including presentation of test results, could be a determinant for a successful implementation. Chigumete, Townsend [27] found that poor communication and inadequate involvement of the employees are barriers to implementing health promoting initiatives in a South African hospital. The nursing and administrative staff pointed out that it might be relevant to involve the nurses further in creating and planning the intervention. It might also be important that the management take a greater responsibility for communicating the hospital’s vision and purpose of the implementation to involve the employees more in the design and planning of the intervention, instead of expecting the communication to be delivered by others. Involving the employees might create a sense of ownership towards the intervention, and elevate the staff’s motivation to the intervention, when applying a participatory approach.

4.2. Work Culture

There was a negative attitude among some nurses towards the intervention. The attitude included irritation and low understanding among each other when a colleague participated in the intervention. Studies have shown that a culture without support to a new approach can be a barrier to participation in health promoting activities [12,23,24,26]. A successful implementation of a health promoting intervention may require a legitimacy from management, participators, and colleagues. A positive atmosphere and joint effort among colleagues may reduce sedentary behavior at work [28].

The study suggested different perceptions of how busy the department was. While some employees indicated that they did not have time to participate in IPET, the management indicated that there was not full occupancy. In recent years, the implementation of a major IT Platform, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the nursing strike in the late summer of 2021, have affected the healthcare staff’s cooperation ability and well-being [29,30]. Figures from 2018 show a similar trend, and the work pressure in Danish hospitals was an issue before COVID-19 [31].This leads to uncertainty as to whether there are work assignments that are invisible to the management: having difficult conversations with patients or time-consuming hygiene tasks. Both examples are quality healthcare tasks that are difficult to measure compared to quantitative measures as occupancy. Furthermore, the busyness and pressure could be the story at the department determining the culture of not being able to participate in training during work.

4.3. Health Ambassadors as Change Agents

When the study was planned, the project group considered utilizing health ambassadors to facilitate participation in the intervention, however, this was not carried out. Change agents can be equated with the mentioned health ambassadors. Utilizing change agents in the study might aid management and the project group. The management and project group can control the project, while the change agents focus on facilitating the wished behavioral change. Daniels, Watson [26] emphasized the importance of securing continuity in the change process, which health ambassadors could possibly assist.

Choosing health ambassadors among the staff and making sure they are accepted of the rest of the staff group, may save resources and easier gain credibility. If health ambassadors were chosen as a part of the future intervention, it would be important to structure their workday, to give them time and make it possible for them to fulfil their new position. Securing that the health ambassadors have the right skills and offering them education in change processes could be essential for their role [

32].

4.4. Implications for Occupational Health Practice

The results of this study are important to consider in the implementation of IPET during working hours in hospitals. Implementing IPET at a hospital, requires a consideration towards the nurses’ and other employees’ workflow and motivations for participating. All participants valued the community-feeling between colleagues, while they missed communication about the intervention and management support towards adjusting the workflow to the setup.

In future interventions, reconciliation of expectations between management and staff is important. Furthermore, it is essential to involve the staff in the intervention before IPET is implemented. Likewise, a long-term successful implementation demands a cultural change. The health ambassadors can contribute to that by driving the change with a positive attitude. This means that when starting the next intervention, management should look at longer perspectives and not only on short-term effects.

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

The strength of this study includes interviews with multiple staff groups within a hospital department, covering different views of the implementation process. We experienced data saturation during our interviews as the informants covered the same topics, with different angles. However, we acknowledge the low number of informants. Although the literature supports the essence of the interviews, we do not know if the results are generalizable in relation to implementation in other hospitals. There may be differences between hospitals, and it is important to use a participatory approach, possibly with small local adjustments. The planned focus groups often turned into single interviews, which gave the interviews another setup than first planned. This meant that we in the single interviews were aware of asking the informant to elaborate answers.

5. Conclusions

Overall, the informants liked the idea of physical exercise training during working hours. Experienced barriers and facilitators varied among the included staff members. Informants from inpatient departments had more difficulties participating in the intervention, whilst those working with more administrative tasks found it easier to prioritize participation. Managers supporting and helping the staff structuring their workdays, and in general involving staff through the entire implementation process was found essential for success. Furthermore, it was important that employees and managers supported the intervention, creating a culture that facilitated participation.

Funding

This work was supported by Nordsjælland’s Hospital (no Grant number)

Conflicts of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants in the study, and the administration of Nordsjælland’s Hospital for their support to the study.

References

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1.9 million participants. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1077–e1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen LB, Andersen LF, FBorodulin HEB, Fagt S, Matthiessen J, Sveinsson T, et al. Nordic Monitoring of diet, physical activity and overweight: First collection of data in alle Nordic Countries: Nordic Council og Ministers; 2011. 167 p.

- Pleis JR, Ward BW, Lucas JW. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey. Vital Health Stat 10 2010, 1-207.

- Pedersen, B.K. The Physiology of Optimizing Health with a Focus on Exercise as Medicine. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2019, 81, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis-Gomar, F.; Lavie, C.J.; Marín, J.; Perez-Quilis, C.; Eijsvogels, T.M.H.; O’keefe, J.H.; Perez, M.V.; Blair, S.N. Exercise effects on cardiovascular disease: from basic aspects to clinical evidence. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 118, 2253–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, K.; Stojanovska, L.; Polenakovic, M.; Bosevski, M.; Apostolopoulos, V. Exercise and mental health. Maturitas 2017, 106, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuoppala, J.; Lamminpää, A.; Husman, P. Work Health Promotion, Job Well-Being, and Sickness Absences—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2008, 50, 1216–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robroek, S.J.; van Lenthe, F.J.; van Empelen, P.; Burdorf, A. Determinants of participation in worksite health promotion programmes: a systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2009, 6, 26–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjøgaard, G.; Justesen, J.B.; Murray, M.; Dalager, T.; Søgaard, K. A conceptual model for worksite intelligent physical exercise training - IPET - intervention for decreasing life style health risk indicators among employees: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Heal. 2014, 14, 652–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalager, T.; Justesen, J.B.; Murray, M.; Boyle, E.; Sjøgaard, G. Implementing intelligent physical exercise training at the workplace: health effects among office workers—a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 116, 1433–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justesen, J.B.; Søgaard, K.; Dalager, T.; Christensen, J.R.; Sjøgaard, G. The Effect of Intelligent Physical Exercise Training on Sickness Presenteeism and Absenteeism Among Office Workers. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 59, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garne-Dalgaard, A.; Mann, S.; Bredahl, T.V.G.; Stochkendahl, M.J. Implementation strategies, and barriers and facilitators for implementation of physical activity at work: a scoping review. Chiropr. Man. Ther. 2019, 27, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jørgensen, M.B.; Villadsen, E.; Burr, H.; Punnett, L.; Holtermann, A. Does employee participation in workplace health promotion depend on the working environment? A cross-sectional study of Danish workers. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilvig, P.M.; Bredahl, T.V.G.; Justesen, J.B.; Jones, D.; Lundgaard, J.B.; Søgaard, K.; Christensen, J.R. Attendance barriers experienced by female health care workers voluntarily participating in a multi-component health promotion programme at the workplace. BMC Public Heal. 2018, 18, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, H.B.; Hansen. M.; Conway, S.H.; Dyreborg, J.; Hansen, J.; Kolstad, H.A.; Larsen, A.D.; Nabe-Nielsen, K.; A Pompeii, L.; Garde, A.H. Short time between shifts and risk of injury among Danish hospital workers: a register-based cohort study. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Heal. 2018, 45, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dansk Sygeplejeråd. SATH Undersøgelse - Sygeplejerskers arbejdsmiljø, trivsel og helbred; 2021.

- Andersen, L.; Clausen, T.; Carneiro, I.; Holtermann, A. Spreading of chronic pain between body regions: Prospective cohort study among health care workers. Eur. J. Pain 2012, 16, 1437–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molsted, S.; Justesen, J.B.; Møller, S.F.; Særvoll, C.A.; Krogh-Madsen, R.; Pedersen, B.K.; Fischer, T.K.; Dalager, T.; Lindegaard, B. Exercise Training during Working Hours at a Hospital Department: A Pilot Study Journal of Occupational and Evironmental Medicine 2022. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Weate, P. Using Thematic Analysis in Sport and Exercise Research In Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise, Smith, B., Sparkes, A.C., Eds. Routledge: New York, 2019.

- Cane, J.; O’connor, D.; Michie, S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement. Sci. 2012, 7, 37–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, J.J.; Stockton, C.; Eccles, M.P.; Johnston, M.; Cuthbertson, B.H.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Hyde, C.; Tinmouth, A.; Stanworth, S.J. Evidense-based Selection of Theories for Designing Behaviour Change Interventions: Using Methods Based on Theoritical Construct Domains to Understand Clinician’s Blood Transfusion Behaviour. British Journal of Health Psychology 2009, 14, 625–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munir, F.; Biddle, S.J.H.; Davies, M.J.; Dunstan, D.; Esliger, D.; Gray, L.J.; Jackson, B.R.; O’connell, S.E.; Yates, T.; Edwardson, C.L. Stand More AT Work (SMArT Work): using the behaviour change wheel to develop an intervention to reduce sitting time in the workplace. BMC Public Heal. 2018, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojo, S.O.; Bailey, D.P.; Brierley, M.L.; Hewson, D.J.; Chater, A.M. Breaking barriers: using the behavior change wheel to develop a tailored intervention to overcome workplace inhibitors to breaking up sitting time. BMC Public Heal. 2019, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, J.W.; Sivertsen, D.M.; Petersen, J.; Nilsen, P.; Petersen, H.V. Barriers and facilitators for implementing a new screening tool in an emergency department: A qualitative study applying the Theoretical Domains Framework. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 2786–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, K.; Watson, D.; Nayani, R.; Tregaskis, O.; Hogg, M.; Etuknwa, A.; Semkina, A. Implementing practices focused on workplace health and psychological wellbeing: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 277, 113888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigumete, T.G.; Townsend, N.; Srinivas, S.C. Facilitating and limiting factors of workplace health promotion at Rhodes University, South Africa. Work 2018, 59, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danquah, I.H.; Kloster, S.; Tolstrup, J.S. “Oh-oh, the others are standing up... I better do the same”. Mixed-method evaluation of the implementation process of ‘Take a Stand!’ - a cluster randomized controlled trial of a multicomponent intervention to reduce sitting time among office workers. BMC Public Heal. 2020, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dansk Sygeplejeråd. Dansk Sygeplejeråds årsrapport 2021; 2021.

- Hagedorn-Rasmussen, P.; Clausen, T.; Abildgaard, J.S.; Aust, B.; Grønvad, M.T.; Lund, H.L.; Thomsen, R. Psykosocialt arbejdsmiljø på regionale arbejdspladser - en kortlægningsrapport; 2021.

- Dansk Sygeplejeråd. SATH Undersøgelse - sygeplejerskers arbejdsmiljø, trivsel og helbred; 2018.

- Kotter, J.P. Leading Change; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, Massachusetts, 1996. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).