Submitted:

19 September 2023

Posted:

20 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conducting a quality appraisal of the retrieved literature

2.2. Data analysis

- Identification of the key findings by reading and re-reading the articles to develop a sense of the studies as a whole.

- The differences and commonalities in the lists of major findings across the studies were compared and contrasted.

- Data display matrices were developed to display all the coded data from each report by category and then were iteratively compared. These categories were used to develop a functional definition of service learning. The product of the synthesis was then written up in the form of a table and a model.

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengthening health promotion and primary prevention

4.2. Collaborative Approach

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- King, ES. A 10-Year Review of Four Academic Nurse-Managed Centers: Challenges and Survival Strategies. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2008, 24, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pohl JM, Sebastian JG, Barkauskas VH, Breer ML, Williams CA, Stanhope M, et al. Characteristics of schools of nursing operating academic nurse-managed centers. Nursing Outlook. 2007, 55, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphreys J, Martin H, Roberts B, Ferretti C. Strengthening an academic nursing center through partnership. Nursing Outlook. 2004, 52, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barger, SE. Academic nursing centers: the road from the past, the bridge to the future. Journal of Nursing Education. 2004, 43, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundeen, SP. Comprehensive, collaborative, coordinated, community-based care: A community nursing center model. Family & Community Health. 1993, 16, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Lundeen, SP. An Alternative Paradigm for Promoting Health in Communities: The Lundeen Community Nursing Center Model. Family & Community Health. 1999, 21, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Newman DML. A community nursing center for the health promotion of senior citizens: based on the Neuman Systems Model. Nursing Education Perspectives. 2005, 26, 221–223. [Google Scholar]

- Neff DF, Mahama N, Mohar DR, Kinion E. Nursing care delivered at academic community-based nurse-managed center. Outcomes Management. 2003, 7, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oros M, Johantgen M, Antol S, Heller BR, Ravella P. Community-based nursing centers: a model for health care delivery in the 21st century. Community-based nursing centers: challenges and opportunities in implementation and sustainability. Policy, Politics & Nursing Practice. 2001, 2, 277–287. [Google Scholar]

- Glick, DF. Advanced practice community health nursing in community nursing centers: A holistic approach to the community as client. Holistic Nursing Practice. 1999, 13, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branstetter E, Holman EJ. An academic nursing clinic's financial survival. Nursing Economics. 1997, 15, 248–252. [Google Scholar]

- Miller KL, Bleich MR, Hathaway D, Warren C. Developing the academic nursing practice in the midst of new realities in higher education. Journal of Nursing Education. 2004, 43, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatti Y, Olsen AL, Pedersen LHJG. The effects of administrative professionals on contracting out. 2009, 22, 121–137.

- Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, Cohen J, Crisp N, Evans T, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. The lancet. 2010, 376, 1923–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenk, J. Reinventing primary health care: the need for systems integration. The Lancet. 2009, 374, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D. Overview of Methods. In: Webb C, Roe B, editors. Reviewing Research Evidence for Nursing Practice: Systematic Reviews. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2007. p. 135-48.

- Kable AK, Pich J, Maslin-Prothero SE. A structured approach to documenting a search strategy for publication: A 12 step guideline for authors. Nurse Education Today. 2012, 32, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, D. Systematic reviews of interpretive research: Interpretive data synthesis of processed data. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002, 20, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

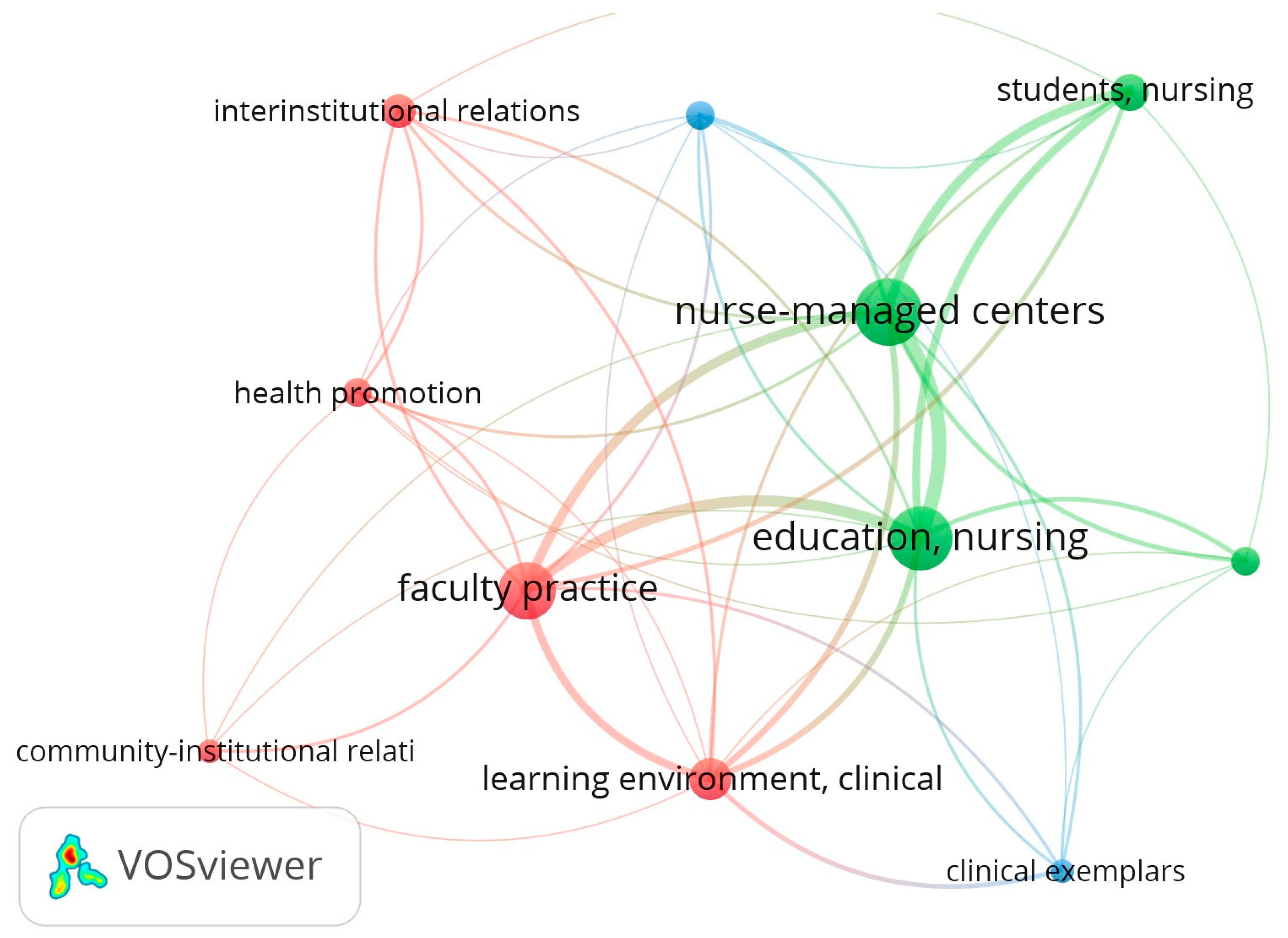

- van Eck NJ, Waltman L. VOSViewer: Visualizing Scientific Landscapes [Software]. 2010.

- Acord LG, Dennik-Champion G, Lundeen SP, Schuler SG. Vision, Grit, and Collaboration: How the Wisconsin Center for Nursing Achieved Both Sustainable Funding and Established Itself as a State Health Care Workforce Leader. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice. 2010, 11, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen PA, McDermott MA. Client satisfaction with student care in a nurse-managed center. Nurse Educator. 1992, 17, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aponte J, Egues AL. A school of nursing-wellness center partnership: creating collaborative practice experiences for undergraduate US senior nursing students. Holistic Nursing Practice. 2010, 24, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkauskas VH, Schafer P, Sebastian JG, Pohl JM, Benkert R, Nagelkerk J, et al. Clients Served and Services Provided by Academic Nurse-Managed Centers. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2006, 22, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connolly PM, Mao C, Yoder M, Canham D. Evaluation of the Omaha System in an academic nurse managed center. Online Journal of Nursing Informatics. 2006, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Connolly, PM. Services for the underserved: a nurse-managed center for the chronically mentally ill. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing & Mental Health Services. 1991, 29, 15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Henry, JK. Community nursing centers: Models of nurse managed care. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing. 1997, 26, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hildebrandt E, Baisch MJ, Lundeen SP, Bell-Calvin J, Kelber S. Eleven years of primary health care delivery in an academic nursing center. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2003, 19, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong W-HS, Lundeen SP. Using ACHIS to Analyze Nursing Health Promotion Interventions for Vulnerable Populations in a Community Nursing Center: A Pilot Study. Asian Nursing Research. 2009, 3, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent F, Keating J. Patient outcomes from a student-led interprofessional clinic in primary care. Journal of interprofessional care. 2013, 27, 336–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krothe JP, Flynn B, Ray D, Goodwin S. Community development through faculty practice in a rural nurse-managed clinic. Public Health Nursing. 2000, 17, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lough, MA. An academic-community partnership: a model of service and education. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 1999, 16, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundeen, SP. Leadership strategies for organizational change: Applications in community nursing centers. Nursing administration quarterly. 1992, 17, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundeen, SP. Community Nursing Centers-Issues for Managed Care. Nursing management. 1997, 28, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundeen SP, Harper E, Kerfoot K. Translating nursing knowledge into practice: An uncommon partnership. Nursing Outlook. 2009, 57, 173–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz J, Herrick CA, Lehman BB. Community partnership: a school of nursing creates nursing centers for older adults. Nursing & Health Care Perspectives. 2001, 22, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marek KD, Rantz MJ, Porter RT. Academic practice exemplars. Senior care: making a difference in long-term care of older adults. Journal of Nursing Education. 2004, 43, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Persily, CA. Academic practice exemplars. Academic nursing practice in rural West Virginia. Journal of Nursing Education. 2004, 43, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pohl JM, Breer ML, Tanner C, Barkauskas VH, Bleich M, Bomar P, et al. National consensus on data elements for nurse managed health centers. Nursing Outlook. 2006, 54, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl JM, Tanner C, Barkauskas VH, Gans DN, Nagelkerk J, Fiandt K. Toward a national nurse-managed health center data set: Findings and lessons learned over 3 years. Nursing Outlook. 2010, 58, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resick LK, Leonardo M, McGinnis K, Stewart J, Goss C, Ellison T. A Retrospective Data Analysis of Two Academic Nurse-Managed Wellness Center Sites. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2011, 37, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiber S, D'Lugoff M. A win-win model for an academic nursing center: Community partnership faculty practice. Public Health Nursing. 2002, 19, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart A, Coulon L, Kavanagh K. The role of a nurse-managed health-care centre in health promotion: A feasibility study. Health Promotion Journal of Australia. 1997, 7, 189–195. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson C, Feeney E. Student-client relationships in a community health nursing clinical setting. Nursing Education Perspectives. 2004, 25, 137–138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tuaoi L-A, Cashin A, Hutchinson M, Graham I. Nurse practitioners in academic nurse managed centres: A new and emergent opportunity for Australian nurses. Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal. 2011, 14, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zandt SE, Sloand E, Wilkins A. Caring for vulnerable populations: role of academic nurse-managed health centers in educating nurse practitioners. Journal for Nurse Practitioners. 2008, 4, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh M, Rong J, Chen M, Chang S, Chung U. Development of a new prototype for an educational partnership in nursing. Journal of Nursing Education. 2009, 48, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zachariah R, Lundeen SP. Research and Practice in an Academic Community Nursing Center. Image: the Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1997, 29, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services: interim report. World Health Organization, 2015.

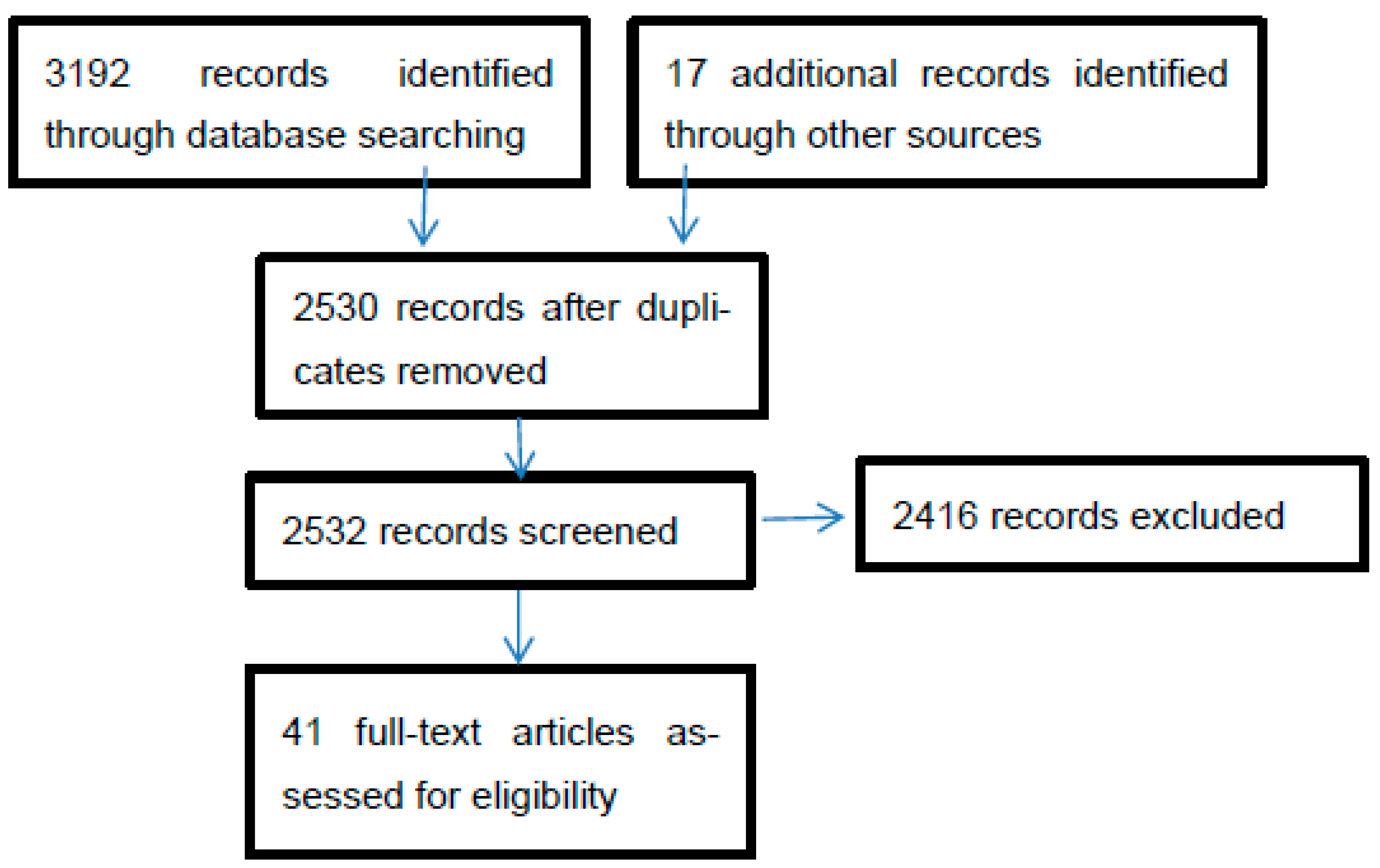

| Literature Search | # Retrieved papers | # Met inclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| CINAHL | 2454 | 21 |

| MEDLINE | 723 | 8 |

| Snowball technique | 17 | 12 |

| Total | 3192 | 41 |

| No | Study (n=39) | Research design | Country | Model | Integration | Contracting Out |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Acord, Dennik-Champion [21] | Not mentioned | USA | The Wisonsin centre for nursing | V | - |

| 2. | Andresen and McDermott [22] | Descriptive | USA | - | V | V |

| 3. | Aponte and Egues [23] | Survey | USA | Wellness centre and SoN partnership | V | V |

| 4. | Barger [4] | Not mentioned | USA | Four era of academic NC | V | - |

| 5. | Barkauskas, Schafer [24] | Cross-sectional survey | USA | Academic nurse-managed centre | - | V |

| 6. | Branstetter and Holman [11] | Not mentioned | USA | Business oriented NC | V | V |

| 7. | Connolly, Mao [25] | Practice exemplars | USA | Academic-nurse managed centre | V | V |

| 8. | Connolly [26] | Pilot project | USA | A nurse managed centre for the chronically mentally ill | V | V |

| 9. | Glick [10] | Discussion paper | USA | Community as client | V | V |

| 10. | Henry [27] | Descriptive | USA | Community nursing centre and service learning | V | V |

| 11. | Hildebrandt, Baisch [28] | Retrospective review | USA | Academic community NC | V | V |

| 12. | Hong and Lundeen [29] | Descriptive | USA | The Lundeen’s comprehensive community-based primary healthcare model | V | V |

| 13. | Humphreys, Martin [3] | Not mentioned | USA | Nurse-managed academic health centre for children and adolescents | V | V |

| 14. | Juniarti et al. 2015 | Case study | Indonesia | Community NC | V | - |

| 15. | Juniarti et al. 2019 | Case study | Indonesia | Community NC | V | - |

| 16. | Kent and Keating [30] | Descriptive | Australia | Student-led inter-professional clinic | V | - |

| 17. | King [1] | 10 years review of 10 academic NCs | USA | Business model | V | V |

| 18. | Krothe, Flynn [31] | Descriptive | USA | Community development model | V | V |

| 19 | Lough [32] | Descriptive | USA | Academic-community partnership | V | V |

| 20. | Lundeen [33] | Not mentioned | USA | Community NC | - | - |

| 21. | Lundeen [5] | Not mentioned | USA | Community NC | V | - |

| 22. | Lundeen [34] | Not mentioned | USA | Community NC | - | V |

| 23. | Lundeen, Harper [35] | Not mentioned | USA | Lundeen Community NC | V | V |

| 24. | Lutz, Herrick [36] | Not mentioned | USA | NC for older adults and service learning | V | V |

| 25. | Marek, Rantz [37] | Descriptive | USA | - | V | V |

| 26. | Miller, Bleich [12] | Not mentioned | USA | Business plan | V | V |

| 27. | Neff, Mahama [8] | Retrospective descriptive | USA | Academic community based nurse-managed centre | - | V |

| 28. | Newman [7] | Descriptive | USA | Neuman Systems model | V | - |

| 29. | Oros, Johantgen [9] | Not mentioned | USA | Community-based NC | V | V |

| 30. | Persily [38] | Practice exemplars | USA | Academic nursing practice | V | V |

| 31. | Pohl, Breer [39] | Survey | USA | Nurse-managed health centres | V | V |

| 32. | Pohl, Sebastian [2] | Survey | USA | - | V | V |

| 33. | Pohl, Tanner [40] | Survey | USA | Primary care nurse-managed centre | - | V |

| 34. | Resick, Leonardo [41] | Retrospective | USA | Nurse-managed wellness centre | - | V |

| 35. | Shiber and D'Lugoff [42] | Descriptive | USA | Academic-community partnership | V | V |

| 36. | Stewart, Coulon [43] | Feasibility study | Australia | Nurse-managed healthcare centre | - | - |

| 37. | Thompson and Feeney [44] | Not mentioned | USA | Academic nursing centre/CHN clinical setting | V | V |

| 38. | Tuaoi, Cashin [45] | Discussion paper | Australia | - | V | - |

| 39. | Van Zandt, Sloand [46] | Case study | USA | Academic nurse managed centre | V | V |

| 40 | Yeh, Rong [47] | Action research | Taiwan | NC and service learning | V | V |

| 41 | Zachariah and Lundeen [48] | Descriptive | USA | Community NC | V | V |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).