Submitted:

15 September 2023

Posted:

20 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

“It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land. Widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and biosphere have occurred.”

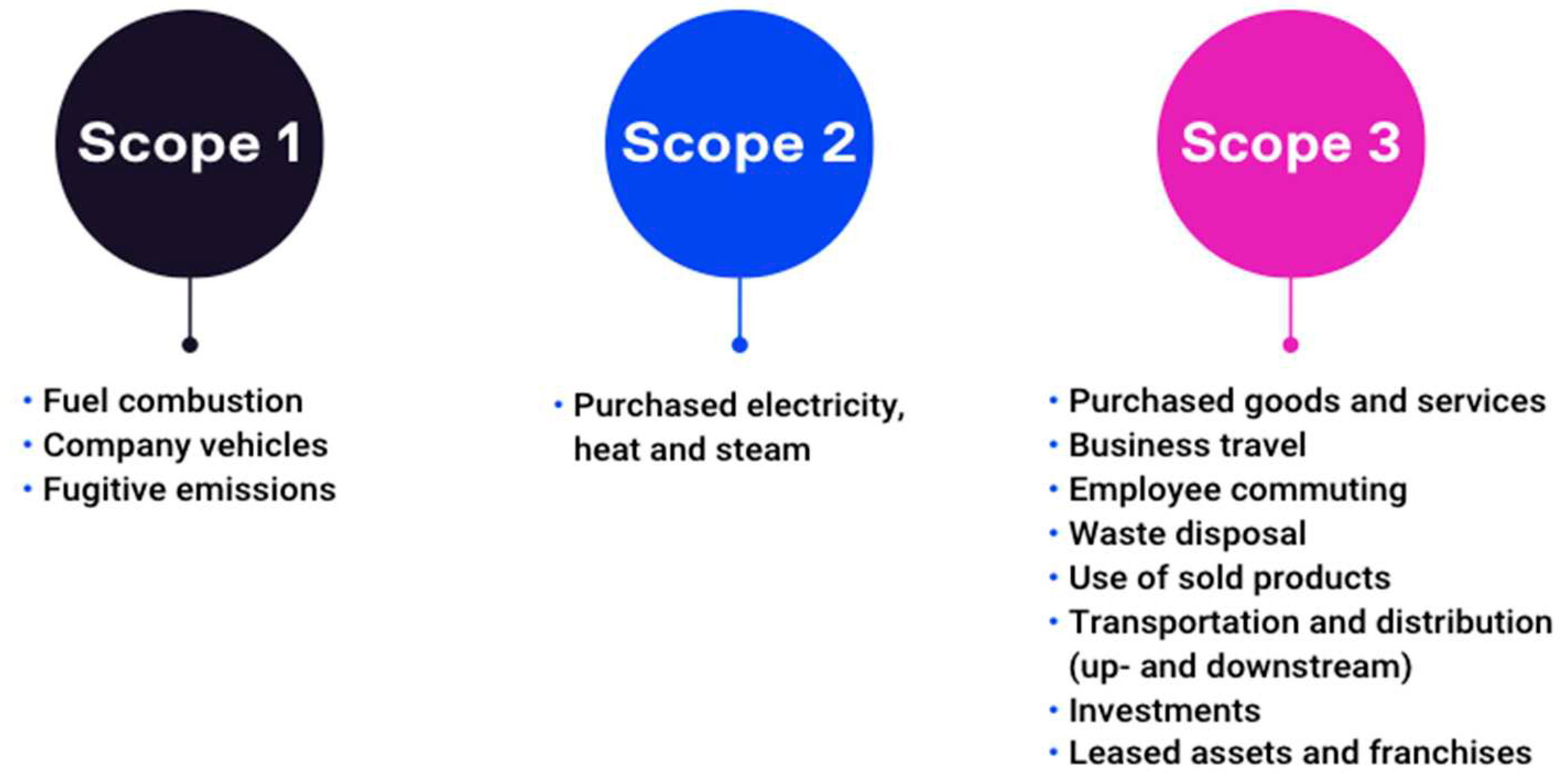

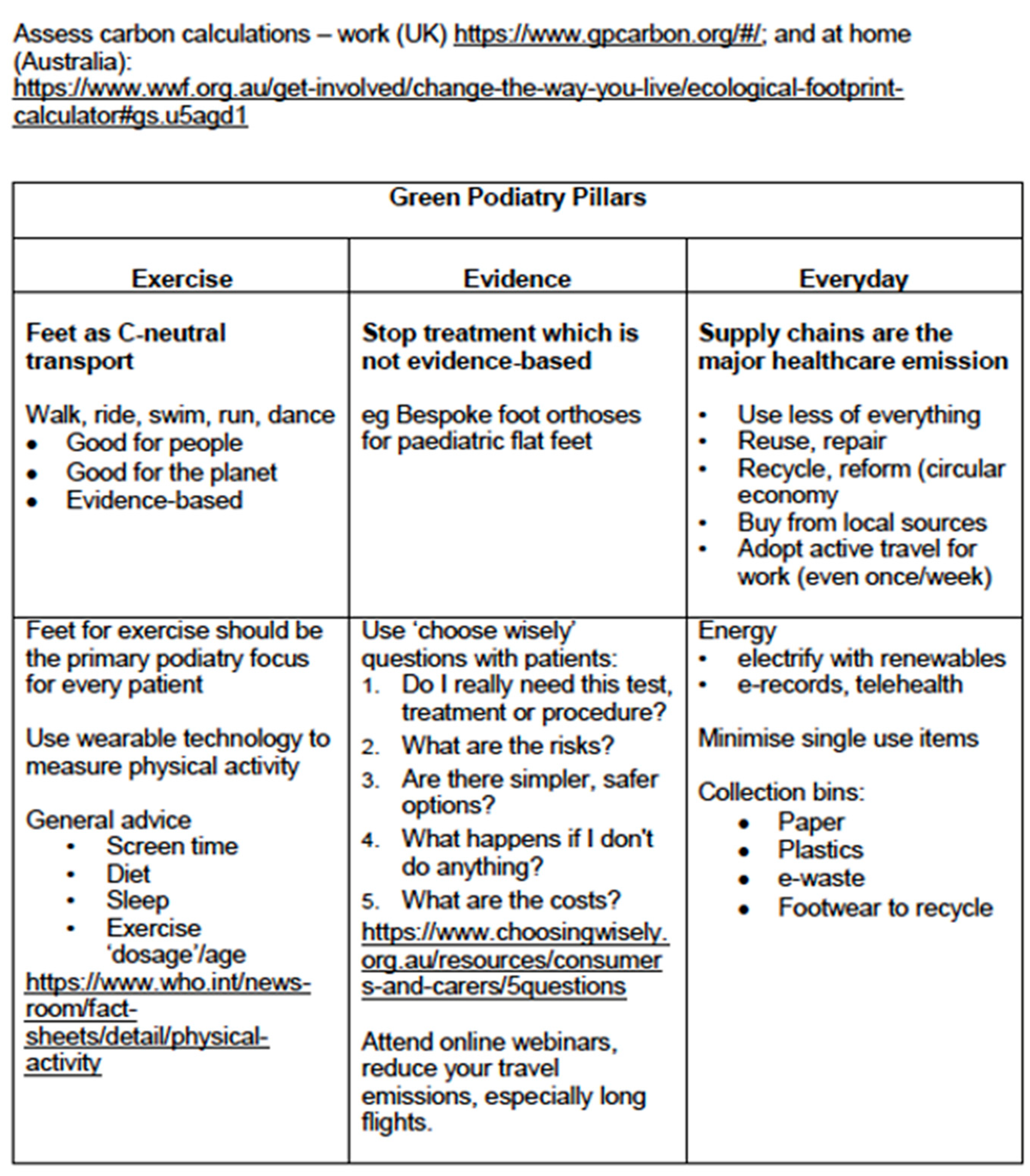

2. Green podiatry pillars

2.1. Exercise

2.2. Evidence

2.3. Everyday action

- Educate yourself – RCPSG course (https://rcpsg.ac.uk/ )

- Promote exercise, which is low carbon, good for health; healthy feet are basic for walking

- Use the evidence, and stop unnecessary intervention

- Use telehealth, especially for initial consultation interviews, progress reviews

- Talk about health and climate change with your patients (Supplementary file)

- Address supply chains – use less, buy locally

- Review energy – use less, use renewable energy

- Footwear – consider what is ethical, sustainably produced; consider repairing, recycling old shoes, stay abreast of possible recycling of foot orthoses (green foot orthoses)

- Use less of everything

- Electrify everything, turn off gas as soon as you can

- Read labels to avoid ultra-processed food (UPF), adopt a plant-based diet (even partially, and grow what you can)

- Divest from fossil fuel companies (check your superannuation)

- Increase your active transport (walk, cycle), plan for electric car

- Vote ‘green’

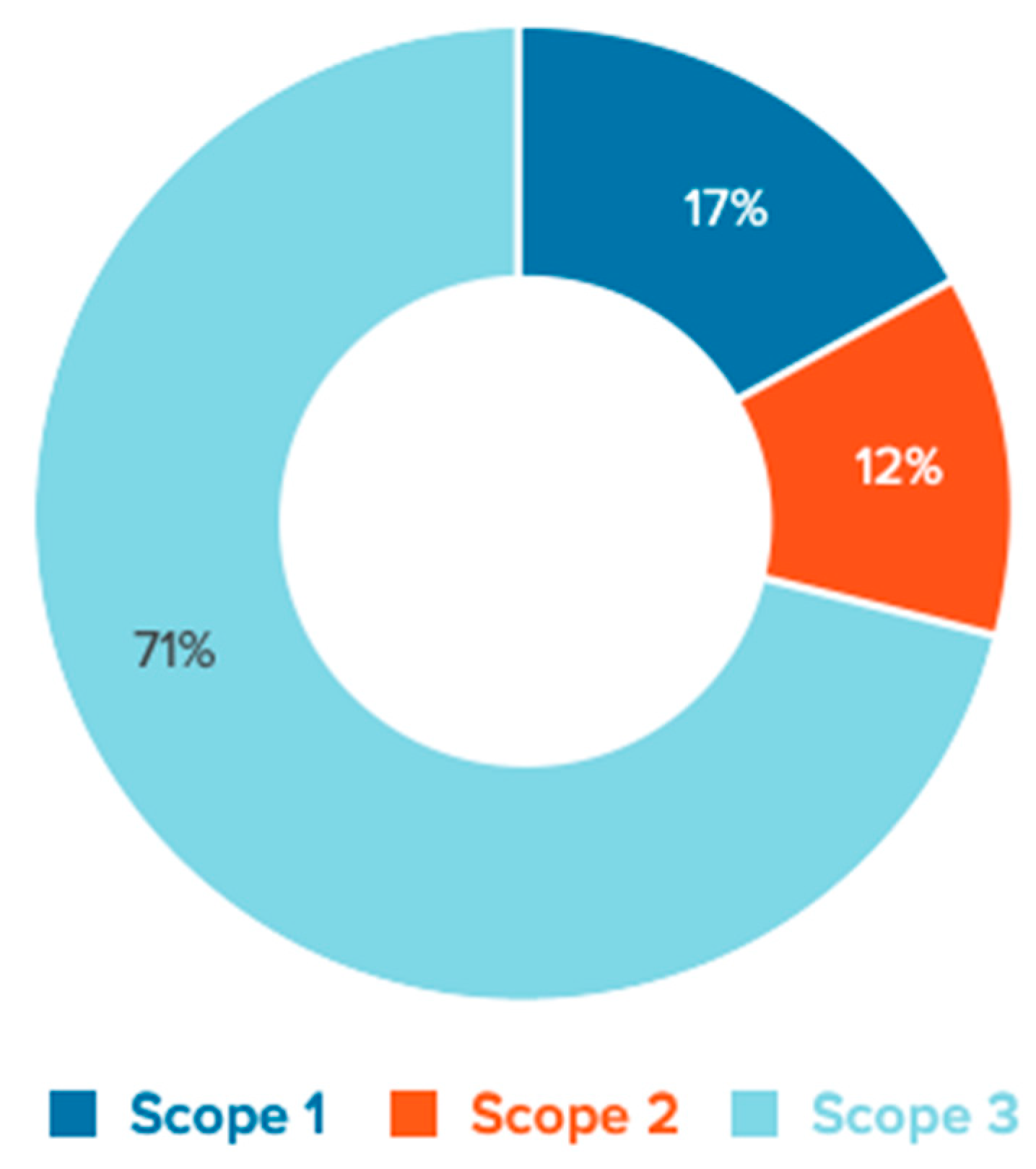

3. Discussion

- Adopting: Adopting a national environmental sustainability policy for health systems

- Minimising: Minimising and adequately managing waste and hazardous chemicals

- Promoting: Promoting an efficient management of resources and sustainable procurement

- Reducing: Reducing health systems’ emissions of greenhouse gases and air pollution

- Prioritising: Prioritising disease prevention, health promotion and public health services

- Engaging: Engaging the allied health workforce as an agent of sustainability

- Increasing: Increasing community resilience and promoting local assets

- Creating: Creating incentives for change

- Promoting: Promoting innovative models of care.

3.1. Putting health before healthcare to prevent diabetes

“Keeping weight in check, being active, and eating a healthy diet can help prevent most cases of type 2 diabetes.”

3.2. Averting costly diabetic feet

4. Conclusions

- Green prescribing34 doses exercise and time in the natural world, is low cost and essential for primary health.

- In the clinic, push back on single use instruments35, adopt renewable and lower energy usage, ‘choose wisely’ and stop unnecessary treatment which drops supply chain emissions.

- Be active yourself, reduce your screen use, avoid UPF foods, and sleep well.

- Partner with existing organisations like Parkrun, advocate for free coffee for regular participants.

- Stop advertising junk foods to children. Australia’s Climate Council has encouraged organisations to remove fossil fuel sponsoring from sports and arts events.

- Avail all housing access to gardens, solar power, rainwater tanks, insulation, electrify everything, and turn off the gas (methane is 25 times more potent than CO2).

- Cycling lanes that are separate and safe – we need political will, rewards, and champions

4.1. Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

- Initiated ‘Green Podiatry’ and has associated publications

- Member of the Sustainability Steering Group - RCPS Glasgow

- Authored Teaching and Learning modules for ‘Green Podiatric Medicine’ – RCPS Glasgow, 2023

- Chair, Sustainability Panel – APodA conference, 2021

- Green foot orthoses project – UNSW SM@RT, APodA collaboration

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Chris van Tulleken, Ultra-processed people, Why we all eat stuff that isn’t food…and why we can’t stop? Cornerstone Press, 27 May, 2023. ISBN-13 978-1529900057. |

References

- Health TLP. Climate risks laid bare. Lancet Planet Heal 2022, 6, e292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spruell T, Webb H, Steley Z, Chan J, Robertson A. Environmentally sustainable emergency medicine. Emerg Med J 2021, 38, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allwright E, Abbott RA. Environmentally sustainable dermatology. Clin Exp Dermatol 2021, 46, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, AM. Sustainable healthcare – Time for ‘Green Podiatry. ’ J Foot Ankle Res 2021, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzen M, Malik A, Li M, Fry J, Weisz H, Pichler P-P et al. The environmental footprint of health care: a global assessment. Lancet Planet Heal 2020, 4, e271–e279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik A, Lenzen M, McAlister S, McGain F. The carbon footprint of Australian health care. Lancet Planet Heal 2018, 2, e27–e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awanthi MGG, Navaratne CM. Carbon Footprint of an Organization: a Tool for Monitoring Impacts on Global Warming. Procedia Eng 2018, 212, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, AM. ‘Green podiatry’ - reducing our carbon footprints. Lessons from a sustainability panel. J Foot Ankle Res 2021, 14, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, Borodulin K, Buman MP, Cardon G et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Brit J Sport Med 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogra S, Ashe MC, Biddle SJH, Brown WJ, Buman MP, Chastin S et al. Sedentary time in older men and women: an international consensus statement and research priorities. Brit J Sport Med 2017, 51, 1526–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gameren M van, Hoogendijk EO, Schoor NM van, Bossen D, Visser B, Bosmans JE et al. Physical activity as a risk or protective factor for falls and fall-related fractures in non-frail and frail older adults: a longitudinal study. Bmc Geriatr 2022, 22, 695. [Google Scholar]

- Park C, Atique MMU, Mishra R, Najafi B. Association between Fall History and Gait, Balance, Physical Activity, Depression, Fear of Falling, and Motor Capacity: A 6-Month Follow-Up Study. Int J Environ Res Pu 2022, 19, 10785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mawer T, Kent K, Williams AD, McGowan CJ, Murray S, Bird M-L et al. The knowledge, barriers and opportunities to improve nutrition and physical activity amongst young people attending an Australian youth mental health service: a mixed-methods study. Bmc Health Serv Res 2022, 22, 789. [Google Scholar]

- Granero-Jiménez J, López-Rodríguez MM, Dobarrio-Sanz I, Cortés-Rodríguez AE. Influence of Physical Exercise on Psychological Well-Being of Young Adults: A Quantitative Study. Int J Environ Res Pu 2022, 19, 4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan R, Doust J, Henry D. Preventing overdiagnosis: how to stop harming the healthy. BMJ 2012, 344, e3502–e3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, B. Back to Basics: Overdiagnosis Is About Unwarranted Diagnosis. Am J Epidemiol 2019, 188, 1812–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale MS, Korenstein D. Overdiagnosis in primary care: framing the problem and finding solutions. Bmj Clin Res Ed 2018, 362, k2820. [Google Scholar]

- Barratt A, McGain F. Overdiagnosis is increasing the carbon footprint of healthcare. Bmj 2021, 375, n2407. [Google Scholar]

- Twohig H, Hodges V, Mitchell C. Pre-diabetes: opportunity or overdiagnosis? Br J Gen Pr 2018, 68, 172–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landewé RBM. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment in rheumatology: a little caution is in order. Ann Rheum Dis 2018, 77, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, K. A system reset for the campaign against too much medicine. Bmj 2022, o1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathirana T, Clark J, Moynihan R. Mapping the drivers of overdiagnosis to potential solutions. Bmj 2017, 358, j3879. [Google Scholar]

- Evans AM, Rome K, Carroll M, Hawke F. Foot orthoses for treating paediatric flat feet. Cochrane Db Syst Rev 2022, 2022, 2022, CD006311. [Google Scholar]

- Launay, F. Sports-related overuse injuries in children. Orthopaedics & traumatology, surgery & research : OTSR 2015, 101, S139–S147. [Google Scholar]

- Redmond AC, Landorf KB, Keenan A-M. Contoured, prefabricated foot orthoses demonstrate comparable mechanical properties to contoured, customised foot orthoses: a plantar pressure study. Journal of foot and ankle research 2009, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brignardello-Petersen R, Guyatt GH, Buchbinder R, Poolman RW, Schandelmaier S, Chang Y et al. Knee arthroscopy versus conservative management in patients with degenerative knee disease: a systematic review. Bmj Open 2017, 7, e016114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher CG, O’Keeffe M, Buchbinder R, Harris IA. Musculoskeletal healthcare: Have we over-egged the pudding? Int J Rheum Dis 2019, 22, 1957–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, AM. Incorporating ‘Green Podiatry’ into your clinic, and into your life. J Foot Ankle Res 2022, 15, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDermott K, Fang M, Boulton AJM, Selvin E, Hicks CW. Etiology, Epidemiology, and Disparities in the Burden of Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Diabetes Care 2022, 46, 209–221. [Google Scholar]

- Tomic D, Shaw JE, Magliano DJ. The burden and risks of emerging complications of diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2022, 18, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks CW, Selvarajah S, Mathioudakis N, Sherman RL, Hines KF, Black JH et al. Burden of Infected Diabetic Foot Ulcers on Hospital Admissions and Costs. Ann Vasc Surg 2016, 33, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong DG, Swerdlow MA, Armstrong AA, Conte MS, Padula WV, Bus SA. Five year mortality and direct costs of care for people with diabetic foot complications are comparable to cancer. J Foot Ankle Res 2020, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunasiri H, Wang Y, Watkins E-M, Capetola T, Henderson-Wilson C, Patrick R. Hope, Coping and Eco-Anxiety: Young People’s Mental Health in a Climate-Impacted Australia. Int J Environ Res Pu 2022, 19, 5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson JM, Jorgensen A, Cameron R, Brindley P. Let Nature Be Thy Medicine: A Socioecological Exploration of Green Prescribing in the UK. Int J Environ Res Public Heal 2020, 17, 3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pegna V, McNally SA. Are single use items the biggest scam of the century? Bulletin Royal Coll Surg Engl 2021, 103, 233–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanello M, Napoli CD, Drummond P, Green C, Kennard H, Lampard P et al. The 2022 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: health at the mercy of fossil fuels. Lancet 2022, 400, 1619–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age (years) | Baseline | Intensity | Sedentary | Screen time | Sleep hours (age) ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended physical activity/ 24 hours | |||||

| < 1 | Floor play several times daily | Include 30 minutes tummy time across the day | Restrained in car seat etc, less than 1 hour at a time | No screens; interactive reading and play | 14 to 17 (<3 mths), 2 to 16 (4 to 11 mths) of good quality sleep, including naps. |

| 1 to 2 | at least 180 minutes of varied PA across the day; more is better | Include some moderate- to vigorous-intensity PA | Restrained in car seat etc, less than 1 hour at a time; limit extended sitting | Age 1 year, sedentary screens not recommended. age 2 years, maximum 1 hour; less is better |

11 to 14 of good quality sleep, including naps; regular sleep times. |

| 3 to 4 | at least 180 minutes of varied PA across the day; more is better | at least 60 minutes is moderate- to vigorous-intensity | Restrained less than 1 hour at a time; limit extended sitting | Sedentary screen time of no more than 1 hour; less is better. | 10 to 13h of good quality sleep; may include a nap; regular sleep times. |

| 5 to 17 | at least 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous intensity, mostly aerobic PA | Include vigorous aerobic PA; add strengthening for muscle and bone, at least 3/week | limit | limit | |

| Recommended PA per week | |||||

| 18 to 64 | at least 150–300 minutes moderate-intensity aerobic PA |

OR at least 75–150 minutes vigorous-intensity aerobic PA |

Limit; Twice or more muscle-strengthening activities at moderate or greater intensity |

limit | |

| > 65 | As for younger adults; older adults should do varied multicomponent physical activity that emphasizes functional balance and strength training at moderate or greater intensity, on 3 or more days a week, to enhance functional capacity and to prevent falls. |

||||

| Pregnant, postpartum (without contraindication) |

at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic PA | include aerobic and muscle-strengthening PA | limit | ||

| Chronic NCD * | at least 150–300 minutes of moderate-intensity | at least 75–150 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic PA | Limit; Twice or more muscle-strengthening at moderate or greater intensity |

||

| People with disability | |||||

| Children and adolescents | at least an average of 60 minutes per day of moderate-to-vigorous intensity PA | vigorous-intensity aerobic PA, as well as those that strengthen muscle and bone, at least 3 days a week | limit | limit | |

| Adults | at least 150–300 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic PA | OR at least 75–150 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic PA |

Limit; Twice or more muscle-strengthening at moderate or greater intensity |

Limit; replace with light intensity PA | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).