1. Introduction

Persistent postural–perceptual dizziness (PPPD) was defined in 2017 [

1] as a syndrome that unifies the clinical characteristics of chronic subjective dizziness, phobic postural vertigo, and related disorders. The ICD-11 describes it as follows: persistent non-vertiginous dizziness, unsteadiness, or both, lasting three months or more. Symptoms are present most days, often increasing throughout the day, but they may wax and wane. Momentary flares may occur spontaneously or with sudden movement. Affected individuals feel worst when upright, when exposed to moving or complex visual stimuli, and during active or passive head motion. These situations may not be equally provocative. Typically, the disorder follows occurrences of acute or episodic vestibular- or balance-related problems but may follow non-vestibular insults as well. [

1,

2,

3]. Symptoms may begin intermittently and then consolidate [

3]. PPPD is considered a chronic functional disease of the brain and a condition in which there is a prolonged and over-adaptive response to acute dizziness, although anxiety itself and other traumatic life events can be a trigger [

1,

3,

4]; however, PPPD is not a structural or psychiatric condition [

3]. Alterations in the functioning of the of the neural structures involved in managing the postural control, locomotion, and spatial orientation represent its primary pathophysiological process [

1,

3] Recently, PPPD was described as secondary, when it is the consequence of an organic disorder (s-PPPD), or primary, when somatic triggers cannot be identified (p-PPPD) [

5]. Among the somatic triggers for s-PPPD, acute unilateral vestibulopathy (AUV) and Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) together with vestibular migraine (VM) are the most common [

5,

6,

7,

8]. BPPV is now considered the most common peripheral vestibular disorder and is believed to be the leading cause of vertigo worldwide [

9] with a lifetime prevalence of 2.4% and an incidence that increases with age [

10,

11,

12]. BPPV is characterized by positional vertigo and nystagmus, provoked by changes in the position of the head with respect to gravity. The diagnosis of BPPV usually is not troublesome, and the outcome of the treatment is very satisfactory with noninvasive methods such as Canalith Repositioning Maneuvers (CRMs) [

9]. In the present study, we evaluated a group of patients diagnosed as s-PPPD, with BPPV as the main somatic trigger, and they were compared with a group of patients affected with BPPV without evolution to PPPD, with the aim of identifying the predictive clinical elements of evolution towards PPPD.

2. Materials and Methods

In the Neurotological unit of the ENT department (tertiary referral center), we retrospectively evaluated the clinical records of a consecutive series of 126 patients diagnosed with PPPD, according to the Barany criteria [

1], during the period of October 2018 to October 2021. All these patients received an accurate history-taking (with the aim of identifying the previous presence of vestibular comorbidities), and they underwent a complete neuro-otological examination, including the search for spontaneous and positional nystagmus (using infrared goggles), caloric testing, video head-impulse test, and cervical and ocular vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (c-Vemps and o-Vemps).

We compared the clinical characteristics of 51 patients with s-PPPD having as the trigger a BPPV (group 1), with a consecutive series of 107 subjects diagnosed as BPPV in the same period but with no evolution to PPPD. Posterior Semicircular Canal -BPPV was diagnosed according to the following criteria [

11]: (a) history of vertigo associated with changes in head position; (b) torsional–vertical nystagmus (with the upper pole of the eye beating toward the affected ear) detected with Frenzel glasses or videoculography in the Dix–Hallpike position; (c) vertigo associated with the elicited nystagmus; (d) latency between completion of the Dix–Hallpike test and the resulting vertigo and nystagmus that increases and resolves within 1 minute. Lateral Semicircular Canal - BPPV was diagnosed according to the following criteria: history of vertigo associated with changes in head position; geotropic or apogeotropic horizontal nystagmus elicited by the supine roll test; vertigo associated with the elicited nystagmus; latency between completion of the supine roll test and the resulting vertigo and nystagmus that increased and resolved within 1 minute [

11].

All the patients suffering from BPPV were successfully treated after 1-3 cycles of CRMs (Semont or Epley maneuver for the BPPV of the posterior semicircular canal and the Gufoni maneuver for the BPPV of the horizontal semicircular canal). We evaluated the following parameters: age, sex, latency between the onset of BPPV and the final diagnosis, recurrence of BPPV, and the presence of migraine.Ethical review and approval by the local Institutional Board (Comitato Etico Azienda Ospedaliero, Universitaria Pisana, Pisa, Italy) were waived for this study. Due to its retrospective nature, it was not set up as part of a research project. Furthermore, the study did not include new experimental diagnostic protocols, and the patients included in the study were diagnosed according to national guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistics

The distribution of qualitative data across the groups was analyzed using the chi-square test and Fisher's exact test, both of which are appropriate for analyzing nonnormally distributed data. Also, the statistical analysis used to assess the correlation between dichotomous variables involved employing the Chi-Square test or the Fisher’s exact test, when appropriate.

To determine the mean differences between quantitative data, the nonparametric Wilcoxon signed rank test was employed, since the data did not follow a normal distribution.

All statistical calculations were performed using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0, IBM, New York, NY). A p-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

In total, 54 patients were classified as p-PPPD and 72 as s-PPPD. In the latter, the vestibular triggers for s-PPPD were represented by BPPV (51 cases, 39 affecting the posterior semicircular canal and 12 the horizontal semicircular canal), VM (12 cases, diagnosed on the basis of the consensus document of the Classification Committee of the Bárány Society, 13), AUV (4 cases), and central vestibular disease (5 cases). We diagnose AUV as a syndrome characterized by rapid onset of severe dizziness without neurologic or audiologic symptoms, unidirectional horizontal nystagmus, unilateral vestibular areflexia/hyporeflexia on bithermal caloric test, and positive head impulse test result in the direction opposite to the fast phase of the nystagmus. 3 of the 5 patients suffering from central vestibular disease resulted affected by vertebro-basilar insufficiency; the remaining 2 patients were affected by cerebral small vessel disease.

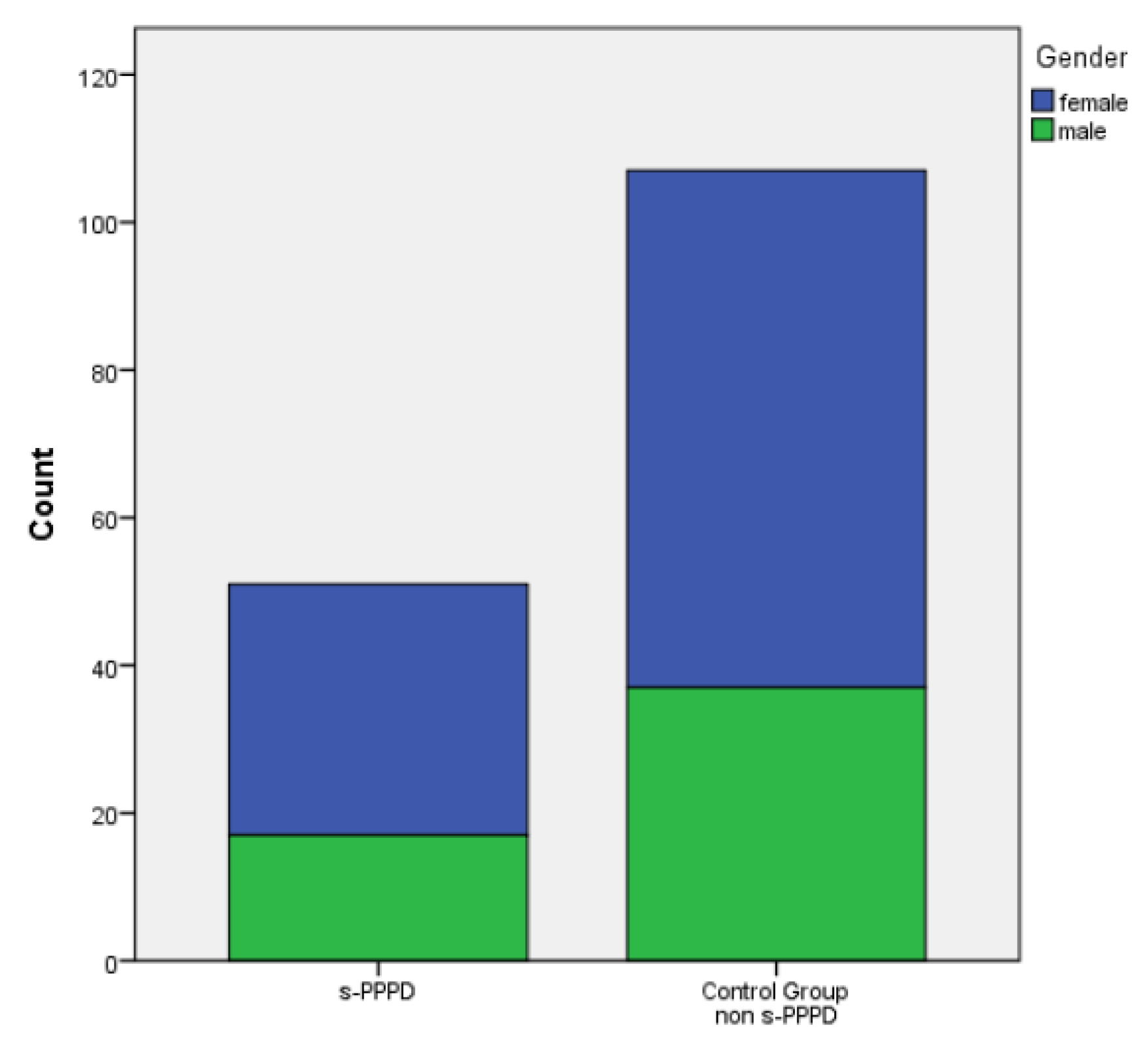

Of the 51 patients with s-PPPD post-BPPV, 34 (66%) were females and 17 (33%) were males, with a mean age of 65.88 years (39 to 80). The control group (patients with previous BPPV and no evolution to PPPD) was constituted by 70 females and 37 males (mean age 53.50 ranging from 27 to 73).

Table 1 shows the demographic data of the two studied groups (

Table 1).

A significant statistical difference in the mean age was found between the s-PPPD and the non-s-PPPD group (p<.001), while no difference was found in the distribution of the sexes in the two groups (

Figure 1).

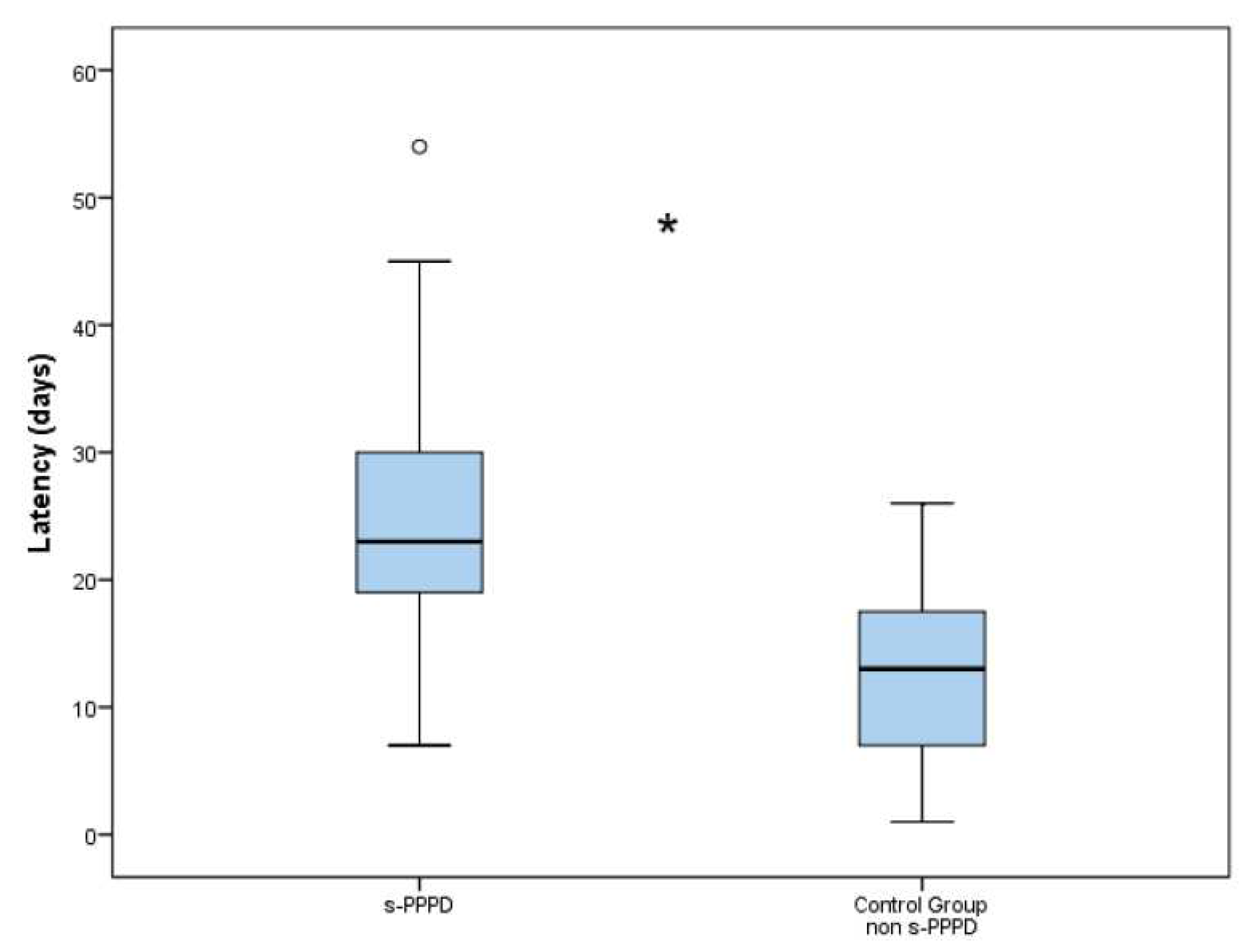

The latency between the onset of BPPV and the final diagnosis was 25.2 days (7 to 54) in group 1 and 12.8 days (3 to 26) in the control group. The difference in the latencies between the s-PPPD and non-s-PPPD groups was statistically significant (p < .001) (

Figure 2).

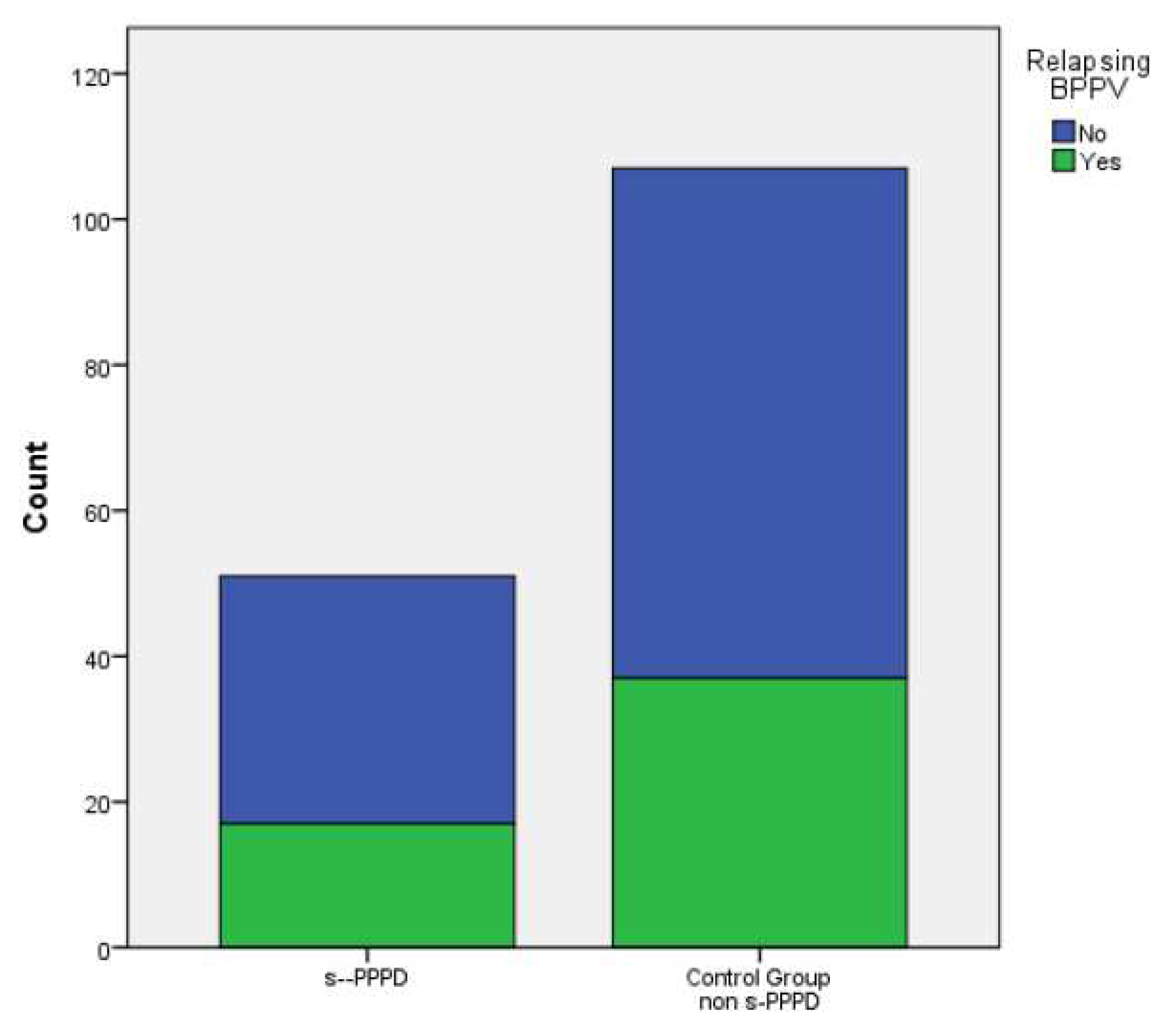

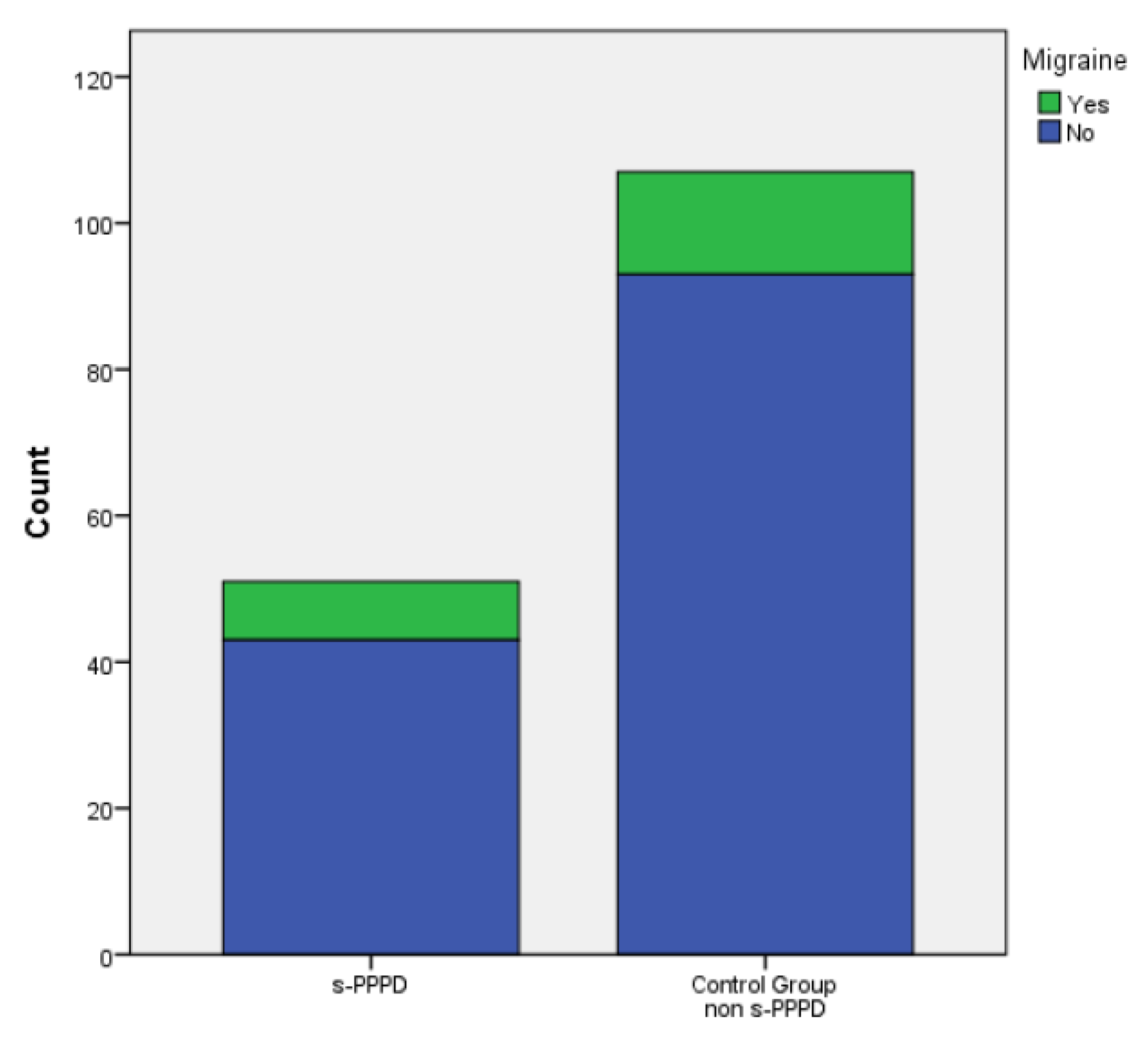

In total, 17 subjects (33%) in group 1 and 37 (34.6%) patients belonging to the control group showed at least one episode of recurrent BPPV (evaluated over a period at least of 14 months). Finally, 8 (15.7%) patients in group 1 and 14 (13.1%) in the control group showed a concurrent migraine. No statistically significant differences were found between the s-PPPD group and the control group in the incidence of relapsing BPPV (p .877) or migraine (p .659)..

No significant distribution differences were found between the sexes andthe occurrence of relapsing BPPV (p .607), or migraine (p .801), or the belonging to the s-PPPD group (p .877) (

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

In the present study, we examined the clinical characteristics of patients who developed a secondary PPPD having a preceding episode(s) of BPPV as a potential somatic trigger. PPPD can arise without any evident somatic trigger or precipitating conditions especially in the presence of psychiatric comorbidities; however, in about half of the cases, PPPD is typically preceded by a disorder of the vestibular system causing acute prolonged or episodic vertigo [

5,

6,

7,

14,

15,

16]. In our series, the most common vestibular precipitant of PPPD was BPPV, and this result is in accordance with those previously reported [

5,

6,

7]. On the contrary, the number of patients suffering from s-PPPD with previous VM was surprisingly low with respect to other experiences [

7,

17,

18]; this result, as well as the finding of a high incidence of cases of PPPD secondary to BPPV, could be attributable firstly to the high prevalence of this disorder in the general population [

10,

19] and secondly to the peculiarity of our center, which could have a lower influx of patients with suspected neurological diseases such as VM. This consideration may also explain the finding of a significant lower mean age in p-PPPD compared to the group of patients classified as s-PPPD. Furthermore, PPPD has been considered as a preexisting spectrum in the nonclinical population, where high levels of PPPD symptoms were found; the vestibular damage could simply play the role of inducing the emergence of a preexisting tendency to an abnormal visuo-vestibular processing leading to visually induced dizziness [

20]. Taking in account the high incidence of BPPV in the context of otoneurological clinical practice, it seemed extremely important to evaluate whether there were some clinical elements that could induce the subsequent onset of PPPD. However, we need to separate s-PPPD subsequent to BPPV from so-called residual dizziness (RD) This condition could occur in up to two-thirds of patients although successfully treated with a repositioning maneuver, and it may manifest as a prolonged and handicapping instability, lightheadedness, and malaise [

21,

22]. The main difference between PPPD and RD is that the latter has a duration that generally does not exceed 20 days [

21,

22,

23,

24], unlike PPPD, the criteria for which indicate a duration of more than three months [

1].

In our experience, the parameters mostly involved as potential precipitants of PPPD subsequent to previous BPPV were represented by the age of the patients and a long latency between the onset of the positional vertigo and the final diagnosis: the mean age of the subjects who developed PPPD was significantly higher than the patients without evolution towards this functional (somatoform) dizziness. In older adults, BPPV tends to have less obvious or less characteristic presentation and a more protracted course [

25], and this condition leads to a greater difficulty in achieving an effective postural control, with the onset of a fear of falling, which can induce psychopathological reactions of anxiety and depression [

11,

26,

27]. The main result of our study seems to demonstrate that a diagnostic delay is the strongly predictive element of an evolution towards PPPD. The finding in the s-PPPD patients of a significantly longer period between the onset of positional vertigo symptoms and the final diagnosis leads us to emphasize the importance of an early identification and treatment of this pathology, reassuring the patient about the benign nature of the disorder. This approach can significantly reduce the possibility that the patient, especially if affected by phobic–anxious personality traits, may develop a condition of chronic dizziness that can be classified as PPPD. A high percentage of patients do not perceive BPPV as a benign disease, causing a serious impact on their health-related quality of life and on their mental state [

28]: the physical limitations caused by the disease and the anxiety and phobic avoidance of the precipitating head position could provoke an exaggerated emotional reaction sometimes persisting for a long period after the vestibular symptoms have resolved [

8,

29], especially in older adults [

28,

29]. Our data confirm that early detection and treatment of BPPV together with reassurance about the benign nature of the disease can undoubtedly decrease the risk of evolution to PPPD, together with a reduction in the negative effects on various aspects of their social and occupational life (work, travel, and social and family life) [

30]. Other parameters, such as the recurrence of BPPV and the presence of concomitant migraine, seem not to be associated with a greater possibility of developing PPPD. This latter observation seems to be in line with the results of a recent study in which it was demonstrated that the presence of VM in the BPPV patient’s history but not migraine without VM appears to increase the risk of developing PPPD in patients with BPPV [

18]. Regarding the recurrence of BPPV, our results confirm the observations of Gambacorta et al [

8] affirming that PPPD occurs mainly in subjects who have suffered from the first episode of BPPV.

This study had several limitations. In our cohort, we did not assess the presence of anxious or depressive personality traits as possible risk factors for developing PPPD after BPPV. It is well known that a high level of anxiety and an exaggerated vigilance towards acute dizzy symptoms are relevant conditions that induce the development of functional dizziness [

2,

3,

4]. Therefore, the lack of an assessment of the patient's psychological status at the time of diagnosis of BPPV is certainly a relevant bias. Another study limitation is represented by the characteristics of the study design: a prospective study with a large cohort of patients will surely introduce a better assessment of the parameters involved as risk factors favoring the evolution towards PPPD after a diagnosis of BPPV.

5. Conclusions

PPPD is a condition characterized by chronic symptoms including subjective dizziness and instability that are typically exacerbated during upright self-motion and during exposure to complex full-field visual stimuli. BPPV is a common vestibular precipitant of PPPD that in these cases could be classified as secondary PPPD. Some parameters seem to be related to the evolution of BPPV into PPPD: the age of the patients and the latency between the onset of the positional attacks of vertigo. For these reasons, early identification, and treatment of BPPV is a crucial clinical task in reducing the risk of evolution towards PPPD, especially in older patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P.C..; methodology, A.P.C., N.V. and L.B.; software, F.L. and N.D.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P.C. and N.D.; writing—review and editing, A.P.C., N.D., F.L. and L.B.; supervision, A.P.C., N.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval by the local Institutional Board (Comitato Etico Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Pisana, Pisa, Italy) were waived for this study. Due to its retrospective nature, it was not set up as part of a research project. Furthermore, the study does not include new experimental diagnostic protocols, and the patients included in the study were diagnosed according to national guidelines, and the study was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Staab, J.P.; Eckhardt-Henn, A.; Horii, A.; Jacob, R.; Strupp, M.; Brandt, T.; Bronstein, A. Diagnostic criteria for persistent postural- perceptual dizziness (PPPD): Consensus document of the committee for the Classification of Vestibular Disorders of the Bárány Society. J Vestib Res 2017, 27, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkirov, S.; Staab, J.P.; Stone, J. Persistent postural- perceptual dizziness (PPPD): a common, characteristic and treatable cause of chronic dizziness. Pract Neurol 2018, 18, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staab, J.P. Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness. Semin Neurol 2020, 2020 40, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieterich, M.; Staab, J.P.; Brandt, T. Functional (psychogenic) dizziness. Handb Clin Neurol 2016, 139, 447–68. [Google Scholar]

- Habs, M.; Strobl. R.; Grill, E.; Dieterich, M.; Becker-Bense, S. Primary or secondary chronic functional dizziness: does it make a difference? A DizzyReg study in 356 patients. J Neurol 2020, 267, 212–222. [CrossRef]

- Huppert, D.K.; Brandt, T. Phobic postural vertigo (154 patients): its association with vestibular disorders. J Audiol Med 1995, 1995 4, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Waterston, J.; Chen, L.; Mahony, K.; Gencarelli, J.; Sturat, G. Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness: Precipitating Conditions, Comorbidities and Treatment with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Front Neurol 2021, 12, 795516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambacorta, V.; D’Orazio, A.; Pugliese, V.; Di Giovanni, A.; Ricci, G.; Faralli, M. Persistent Postural Perceptual Dizziness in Episodic Vestibular Disorders. Audiol Res 2022, 12, Audiol Res. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuti, D.; Zee, D.S.; Mandalà, M. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: what we do and do not know. Semin Neurol 2020, 40, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Brevern, M.; Radtke, A.; Lezius, F.; Feldmann, M.; Ziese, T.; Lempert, T.; Neuhauser, H. Epidemiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a population-based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007, 78, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, N.; Gubbels, S.P.; Schwartz, S.R.; Edlow, J.A.; et al. Clinical practice guideline: benign paroxysmal positional Vertigo (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017, 156, S1–S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Zee, D.S. Clinical practice. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. N Engl J Med 2014, 370, 1138–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempert, T.; Olesen, J.; Furman, J.; Waterston, J.; Seemungal, B.; Carey, J.; Bisdorff, A.; Versino, M.; Evers, S.; Newman-Toker, 357 D. Vestibular migraine: diagnostic criteria. J Vestib Res. 2012, 22, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, T.; Huppert, D.; Strupp, M.; Dieterich, M. Functional dizziness: diagnostic keys and differential diagnosis. J Neurol 2015, 262, 1977–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabaya, K.; Tamai, H.; Okajima, A.; Minakata, T.; Kondo, M.; Nakayama, M.; Iwasaki, S. Presence of exacerbating factors of persistent perceptual-postural dizziness in patients with vestibular symptoms at initial presentation. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol 2022, 7, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murofushi, T.; Nishimura, K.; Tsubota, M. Isolated Otolith Dysfunction in Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness. Front Neurol 2022, 13, 872892–872892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, C.; Eckhardt-Henn, A.; Tschan, R.; Dieterich, M. Psychiatric morbidity and comorbidity in different vestibular vertigo syndromes. Results of a prospective longitudinal study over one year. J Neurol 2009, 256, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropiano, P.; Lacerenza, L.M.; Agostini, G.; Barboni, A.; Faralli, M. Persistent postural perceptual dizziness following paroxysmal positional vertigo in migraine. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2021, 41, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhauser, H.K. The epidemiology of dizziness and vertigo. Handbook Clin Neurol 2016, 137, 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Powell. G.; Derry-Sumner, H.; Rajenderkumar, D.; Rushton, S.K.; Sumner, P. Persistent postural perceptual dizziness is on a spectrum in the general population. Neurology 2020, 94, e1929–e1938. [CrossRef]

- Teggi, R.; Quaglieri, S.; Gatti, O.; Benazzo, M.; Bussi, M. Residual dizziness after successful repositioning maneuvers for idiopathic benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. ORL 2013, 75, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martellucci, S.; Pagliuca, G.; De Vincentiis, M.; Greco, A.; De Virgilio, A.; Nobili Benedetti, F.M.; Gallo, A. Features of residual dizziness after canalith repositioning procedures for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016, 154, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seok, J.; Lee, H.M.; Yoo, J.H.; Lee, D.K. Residual dizziness after successful repositioning treatment in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Clin Neurol 2008, 4, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faralli, M.; Lapenna, R.; Giommetti, G.; Pellegrino, C.; Ricci, G. Residual dizziness after the first BPPV episode: role of otolithic function and of a delayed diagnosis. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngol 2016, 273, 3157–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balatsouras, D.G.; Koukoutsis, G.; Fassolis, A.; Moukos, A.; Apris, A. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in the elderly: current insights. Clin Intervent Aging 2018, 13, 2251–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumani, K.; Powell, J. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: management and its impact on falls. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2017, 126, 602–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casani, A.P.; Gufoni, M.; Capobianco, S. Current Insights into Treating Vertigo in Older Adults. Drugs Aging 2021, 38, 38,655–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámiz, M.J.; Lopez-Escamez, J.A. Health-related quality of life in patients over sixty years old with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Gerontology 2004, 50, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Escamez, J.A.; Gamiz, M.J.; Fernandez-Perez, A.; Gomez-Fiñana, M.; Sanchez-Canet, I. Impact of treatment on health-related quality of life in patients with posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otol Neurotol 2003, 24, 637–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronstein, A.M., Golding, J.F.; Gresty, M.A.; Mandalà, M.; Nuti, D.; Shetye, A.; Silove, Y. The social impact of dizziness in London and Siena. J Neurol 2010, 257, 183–190.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).