1. Introduction

Sleep is important for overall health and well-being. Insufficient sleep and sleep disorders are highly prevalent and associated with adverse health outcomes [

1]. Sleep health is a recent public health concept introduced in 2014 that addresses both insufficient sleep and sleep disorders in order to respond to this public health issue [

2]. It is particularly important in the design and evaluation of behavioral sleep strategies, which could benefit populations at risk, such as healthcare workers. Indeed, these professionnals have atypical working schedule with frequent night shifts and on-call duties [

3]. In addition, they are exposed to experienced stress that led to loss of sleep and manifested symptoms of sleep deprivation. Mental complaints can affect a physician’s health. They also lead to an increased number of medical errors [

4]. In 2020, healthcare workers have been facing a dramatic pandemic with extreme work pressure, fast adaptations to intense critical care situations, unseen amounts of severe critical patients, numerous deaths of patients, and risks of infection. Lockdowns, social distancing, quarantines, fear about oneself and ones loved ones, and economic consequences have further increased sleep disruptions in this population [

5]. Sleep hygiene is defined as a set of behavioral and environmental recommendations intended to promote sleep health. Research has demonstrated links between individual sleep hygiene components and subsequent sleep [

6]. To our knowledge, sleep hygiene has not been evaluated among French healthcare worker population. Our study was aimed to determine the prevalence of poor sleep hygiene and mental complaints and their associations in a French healthcare worker population.

2. Methods

This study used an observational cross-sectional design set between summer 2020. All professionals working in the Bordeaux University Hospital were asked to answer an internet-based questionnaire. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and met the requirements for processing health data as described by the French national commission for informatics and liberties.

Participants were asked about their socio-demographical data (age, gender, profession and financial situation), their work schedules (night and/or shifted) and their Covid-19 exposure (work in a Covid-19 unit).

Concerning sleep hygiene, participants were asked, during workdays and during free days, what time they usually go to (bedtime) and get up (getting up time) and how many hours of actual sleep did they get (sleep duration). From these answers were then estimated proxies of their sleep hygiene: mean sleep duration (including workdays and free days), sleep efficiency (ratio of mean sleep duration over time-in-bed), sleep rebound (as the difference between mean sleep duration before workdays and before free days) and social jetlag (as the difference between mid-sleep during workdays and mid-sleep during free days, mid sleep as the middle between bedtime and getting up time [

9]). Mean sleep duration was categorized into 3 groups: less than 6 hours, between 6 hours and 7 hours and more than 7 hours. Sleep efficiency was categorized into 3 groups: less than 85%, between 85% and 95% and more than 95%. Sleep rebound and social jetlag were defined as at least 2 hours shift.

Concerning mental complaints, insomnia was assessed with the Insomnia Severity Scale (ISI), a 7-item scale rated on a 5-point Likert scale [

9]. We consider a score of 15 or above as moderate or severe insomnia. Excessive Daytime Sleepiness (EDS) was measured using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), a validated scale exploring eight everyday situations rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “would never doze” to “high chance of dozing”. We consider a score of 16 or above as severe EDS [

10]. Fatigue was measured using a single item inspired by the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI): “Do you feel tired in connection with your work?” followed by a 7-point Likert scale from “Never” to “Daily” [

11]. A frequency greater than once a week was considered to indicate significant fatigue. Anxiety et depressive symptoms were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire 4 (PHQ-4), a short scale with 4 items rated on a 3-point Likert scale [

12]. The first two items are summed to obtain the anxiety score and the last two to obtain the depressive score. We considered the participant to have significant “anxiety” or “depression” when the score was 3 or more on the specific scale.

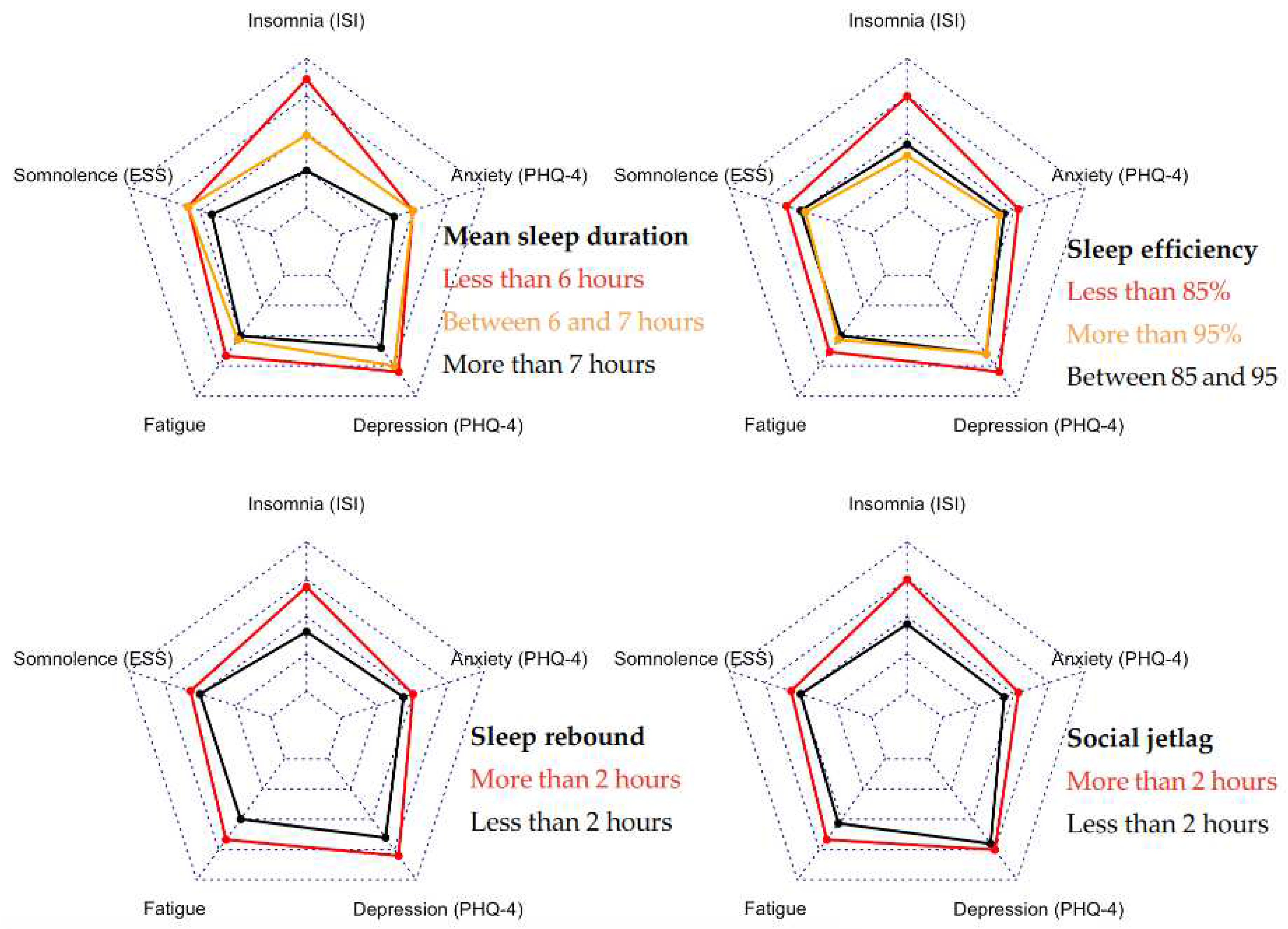

Descriptive statistics were calculated as frequencies (%) for categorical variables, whereas means and standard deviations were computed for continuous variables. Univariate associations were presented using radar charts with the interquartile range as the scale. Multivariate associations were obtained using logistic regression to calculate odds-ratio (OR) and their 95% confidence interval (CI) between sleep-wake timings and significant mental complaints. Models were adjusted for age, gender, profession, financial situation and work schedules. In each model, we tested for interactions with exposure to Covid-19, finding no significant interaction. For all the tests, the accepted significance level was 5%. Data analyses were conducted using R v.3.4.3.

3. Results

Participants included 1,562 adults ranging from 18 to 75 years old (40.0±11.2) which represented 12.5% of the 12,495 Bordeaux University Hospital’s professionnals. Participants were predominately women (80.5%) and at least bachelor’s degree (91.2%). Mean sleep duration was 6h45±55′ with 25.9% of participants sleeping less than 6 hours, mean sleep efficiency was 89%±9% with 24.3% of participants having less than 85%. A total of 27.3% of participants reported a sleep rebound of more than 2 hours and 11.5% reported a social jetlag of more than 2 hours. Mean ISI was 11.9±5.6 with 33.9% of significant insomnia and mean ESS was 10.1±4.7 with 45.1% of significant EDS. A total of 13.1% of participants reported fatigue more than once a week, 16.5% reported significant depression and 35.7% reported significant anxiety (

Table 1).

Participants sleeping less than 6 hours reported more insomnia and fatigue than those sleeping between 6 and 7 hours (

Figure 1). Mental complaints were further reduced in those sleeping more than 7 hours (mean ISI: 10.0 vs. 11.9 and 14.9, mean fatigue: 3.5 vs. 3.6 and 4.0). Participants having a sleep efficiency less than 85% reported more mental complaints than those having a sleep efficiency between 85% and 95% or those having more than 95%. Results were similar with sleep rebound and social jetlag of more than 2 hours.

Results of multivariate logistic regression are presented in

Table 2. After adjustment for age, gender, profession, financial situation and work schedules, mean sleep duration was associated with insomnia (p<0.001), EDS (p=0.031), depression (p<0.001) and anxiety (p<0.001) but not with fatigue (p=0.646). The frequency of insomnia and anxiety were respectively 4-times higher and 2-times higher in participants sleeping less than 6 hours compared to participants sleeping more than 7 hours. Sleep efficiency less than 85% was associated with each mental complaint (OR ranging from 1.4 for EDS to 1.9 for insomnia and fatigue). A sleep rebound of more than 2 hours was associated with significant insomnia and fatigue (respectively OR=1.5 [1.2-2.0] p=0.001 and OR=1.5[1.1-2.1] p=0.026). Social jetlag was associated with significant insomnia (OR=1.9 [1.3-2.7] p<0.001) but no other mental complaints.

4. Discussion

This study found that poor sleep hygiene and mental complaints were frequent in healthcare workers during Covid-19 crisis. These results were consistent with two recent meta-analysis. The first published in 2020 found a prevalence of insomnia, anxiety and depression of 34.3%, 23.2% and 22.8% in a population of 33,000 healthcare workers included from 13 studies [

13]. The second published in 2021 with 52,000 healthcare workers included from 22 studies found a prevalence of sleep disorders, anxiety and depression of 44.0%, 30.0% and 31.1% [

14]. More particularly in France, a 2020 study carried out among 1,001 young surgeons found that 43.1%, 35.9% and 40.8% had respectively significant insomnia, anxiety and depression [

15]. In our study, mental complaints were less frequent, especially for depression (16.5%), which can be explained by the fact that our questionnaire took place during the summer of 2020 between two epidemic waves. Before the outbreak, a meta-analysis published in 2020 found a sleep disturbances prevalence of 39.2% in a population of 32,000 Chinese healthcare workers [

16]. In France, a 2015 study found an average sleep duration (6.5 hours) and a prevalence of EDS (44%) equivalent to ours in a population of anesthesiologists and intensivists [

17]. These elements show that the Covid-19 crisis has worsened an already tense situation for healthcare workers. The deployment of behavioral sleep strategies could therefore be beneficial during the pandemic and even afterwards. Our study also found a fairly low prevalence of social jetlag, which is consistent with studies that showed it improved over this period [

18]. Our results showed that sleep efficiency and mean sleep duration were associated with each of the mental complaints except fatigue with mean sleep duration, suggesting that these are the two most important dimensions of sleep hygiene in preventing mental complaints. Social jetlag and sleep rebound were both associated with insomnia but not with EDS, anxiety or depression. These results lead us to consider the importance of the following three behavioral sleep strategies, in this order: (i) Not staying awake in bed, (ii) Sleeping more than 6 hours per night, (iii) Keeping regular rhythms on weekends. The challenge now is to promote these messages, in partnership with occupational health services, and using validated interventions, with the aim of modifying sleep behavior and ultimately improving the sleep and mental health of these professionals.

Our study has some limitations. First, participants were included on a voluntary basis, so people interested in the issue of sleep were over-represented. However, the sample was representative of the overall population of Bordeaux healthcare workers in terms of age (43.0 vs. 40.0) and gender (80.0% vs. 80.5% of women). Second, the self-administered questionnaire may have led to some misclassification and no objectives measures were used to assess sleep-wake timings. However, we only used validated scale. Further studies should explore how objective and subjective measures correlate with each other and with mental complaints. Third, our analyses were only cross-sectional and did not inform on the direction of the relationship between sleep hygiene and mental complaints. The exact mechanisms underlying these associations remain speculative and should be explored in longitudinal studies.

5. Conclusions

Healthcare workers are a specific population with a high prevalence of poor sleep hygiene and mental complaints. The Covid-19 crisis has worsened an already tense situation. The promotion of sleep health through behavioral sleep strategies should be encouraged to ensure good health for these professionals and good quality of care for their patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C., J.-A.M.-F., P.P.; methodology, J.-A.M.- F., P.P.; software, J.-A.M.-F. and P.P.; validation, J.-A.M.-F., P.P.; formal analysis, J.C. and J.-A.M.-F.; investigation, J.C. and J.-A.M.-F.; resources, J.-A.M.-F. and P.P.; data curation, J.-A.M.-F. and P.P.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C. and J.-A.M.-F.; writing—review and editing, J.C., P.P. and J.-A.M.-F.; visualization, J.C. and J.-A.M.-F.; supervision, J.-A.M.-F. and P.P.; project administration, J.-A.M.-F. and P.P.; funding acquisition, P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and met the requirements for processing health data as described by the French national commission for informatics and liberties.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere acknowledgement to all the professionals involved in the questionnaire design, including Rachel Debs. They also thank Christophe Gauld and Kevin Ouazzani for their expertise in clarifying the different dimensions of sleep and sleep health. Finally, the authors acknowledge Bordeaux University Hospital for its help in recruiting the participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Garbarino S, Lanteri P, Durando P, Magnavita N, Sannita WG. Co-Morbidity, Mortality, Quality of Life and the Healthcare/Welfare/Social Costs of Disordered Sleep: A Rapid Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Buysse, DJ. Sleep health: can we define it? Does it matter? Sleep 2014, 37, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck F, Léon C, Pin-Le Corre S, Léger D. [Sleep disorders: Sociodemographics and psychiatric comorbidities in a sample of 14,734 adults in France (Baromètre santé INPES)]. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2009, 165, 933–942. [Google Scholar]

- Léger D, Guilleminault C, Bader G, Lévy E, Paillard M. Medical and socio-professional impact of insomnia. Sleep 2002, 25, 625–629. [Google Scholar]

- Wu K, Wei X. Analysis of Psychological and Sleep Status and Exercise Rehabilitation of Front-Line Clinical Staff in the Fight Against COVID-19 in China. Med Sci Monit Basic Res. 2020, 26, e924085. [Google Scholar]

- Irish LA, Kline CE, Gunn HE, Buysse DJ, Hall MH. The role of sleep hygiene in promoting public health: A review of empirical evidence. Sleep Med Rev. 2015, 22, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed DL, Sacco WP. Measuring Sleep Efficiency: What Should the Denominator Be? J Clin Sleep Med JCSM Off Publ Am Acad Sleep Med. 2016, 12, 263–266. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann M, Dinich J, Merrow M, Roenneberg T. Social jetlag: misalignment of biological and social time. Chronobiol Int. 2006, 23, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001, 2, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminska M, Jobin V, Mayer P, Amyot R, Perraton-Brillon M, Bellemare F. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale: self-administration versus administration by the physician, and validation of a French version. Can Respir J. 2010, 17, e27–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. 3rd édition. Menlo Park, CA: Consulting Psychologists Pr; 1996.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Löwe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 2009, 50, 613–621. [Google Scholar]

- Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020, 88, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvaldi M, Mallet J, Dubertret C, Moro MR, Guessoum SB. Anxiety, depression, trauma-related, and sleep disorders among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021, 126, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallée M, Kutchukian S, Pradère B, Verdier E, Durbant È, Ramlugun D, et al. Prospective and observational study of COVID-19′s impact on mental health and training of young surgeons in France. Br J Surg. 2020, 107, e486–e488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu D, Yu Y, Li R-Q, Li Y-L, Xiao S-Y. Prevalence of sleep disturbances in Chinese healthcare professionals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2020, 67, 258–266. [Google Scholar]

- Richter E, Blasco V, Antonini F, Rey M, Reydellet L, Harti K, et al. Sleep disorders among French anaesthesiologists and intensivists working in public hospitals: a self-reported electronic survey. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2015, 32, 132–137. [Google Scholar]

- Zamarian L, Högl B, Delazer M, Hingerl K, Gabelia D, Mitterling T, et al. Subjective deficits of attention, cognition and depression in patients with narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2015, 16, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).