1. Introduction

Diagnosis of diabetes in children can be a daunting experience for parents, who are suddenly faced with the responsibility of managing their child's illness [

1]. Insulin therapy is a critical component of diabetes management, but it can be challenging for parents to navigate the complexities of administering insulin to their child [

2]. Additionally, some parents may experience phobias or barriers that prevent them from effectively managing their child's diabetes [

3,

4].

Several studies have highlighted the challenges that parents face in managing their child's diabetes, including the fear of hypoglycemia, the burden of daily insulin administration, and the impact of diabetes on family life [

5]. In addition, some parents may experience phobias or barriers to insulin use, such as needle phobia or concerns about the long-term effects of insulin therapy [

6]. A study found that young children felt higher fear and pain with needles than older respondents. At the time of diagnosis, a substantial percentage of mothers reported intense fear of needles [

7]. Although the majority of mothers recuperate, 13.6% continue to experience severe dread and distress for at least 6 to 9 months. Mothers' who continued reporting significant distress was associated with children's poor collaboration, which was associated with poorer diabetes control [

7]. As needle anxiety and phobia have been categorized as neglected diseases, it is believed that 22% of the general population suffers from some level of needle anxiety [

8]. Affected individuals develop a vasovagal response with symptoms of lowering blood pressure during injections, resulting in dizziness, fainting, sweating, and nausea [

8]. This phobia tends to run in families, so several family members may have comparable concerns and reactions [

8,

9]. Furthermore, some parents and children may avoid blood glucose tests and injections to prevent disagreement, leading to poorer diabetes control. Engaging the parent first to develop a routine soothes the parent and enhances the child cooperation upon dose administration [

7]. The practice of this process, first as a simulation and then "real," provides both the youngster and the parent with an active method to deal with needles. If children and parents continued to experience needle fear, they should be referred for continued counseling or psychotherapy [

7].

These factors can have a significant impact on diabetes management and can lead to suboptimal glycemic control, which can increase the risk of complications in the long term [

10]. Understanding the factors that influence insulin use among parents of diagnosed children with diabetes is crucial for developing effective interventions to improve diabetes management. By identifying the specific challenges and barriers that parents face, healthcare providers can provide targeted support and education to help parents overcome these obstacles and manage their child's diabetes effectively. In this article, this study aims to assess the experience, fears, barriers and adherence to insulin use among the parents of diagnosed children with diabetes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Study Participants

This study followed a descriptive cross-sectional design, which was conducted using an online survey. It followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement for cross-sectional studies. Participants' recruitment was performed by convenience sampling technique. Participants were approached through research assistants at the Jordan University hospital. The inclusion criteria for the study participants were residents in Jordan, and parents of children (<18 years old) with a diagnosed type 1 diabetes. Parents filled out the survey on behalf of their children after completing a consent form at the start of the survey to ensure their eligibility and willingness to participate.

2.2. Minimal Sample Size Calculation

The sample size was estimated using G*Power software was used to determine the minimum sample size. The minimum required sample size was 183 participants, considering an alpha error of 5%, a power of 80%, a minimal model R-square of 10% and allowing 15 predictors to be included in the model.

2.3. Study Tool

The online survey was developed after reviewing/adopting related validated surveys in the literature [

11,

12,

13,

14]. A draft survey was designed, then examined for fitness of purpose and face validity by a group of five experts in observational studies. Following this review, the final version of the survey was translated into Arabic using the "translation and back translation" approach. Then, the survey was piloted in a sample of 10 volunteers to verify its comprehension, clarity, and cultural acceptability before moving on to the primary survey. The data obtained from the pilot test were not included in the final data analysis. The survey contained multiple-choice questions and was designed to be completed within 15 minutes.

The study was conducted in Jordan, between Feb-March 2023. The online survey was uploaded on the Google Forms platform. Then, it was distributed to the participants. A written participant consent statement "Your participation in completing this survey is highly appreciated" was given to the participants at the beginning of the study. If the participants were willing to proceed with the survey, they approved their consent. If not, they selected "disagree to participate" and did not continue with the survey questions. Potential participants who completed the survey were considered to have given informed consent for their participation in the study. The participants' names were not requested, so the anonymity of respondents would be preserved. To maintain confidentiality, the entire data file was downloaded and saved on the investigator's computer.

The final version of the survey was composed of six main sections. The first section included sociodemographic questions about children with diabetes. The second section included sociodemographic questions for participating parents on behalf of their children with diabetes. The third section evaluated the experience of the participants with insulin, if they have ever used it, the duration of use, and their experience with the plausible side effects. The fourth section evaluated the diabetes fear of self-injecting questionnaire (D-FISQ). The D-FISQ was created to assess patients with diabetes who needed insulin therapy for their fear of self-injecting and self-testing. The D-FISQ consists of 15 items, including items for fear of self-injecting and dread of self-testing. Each response is graded on a 4-point Likert scale; 1: almost never, 2: Sometimes, 3: Often, 4: Almost all the time. Calculating the mean raw score for each sub-dimension was conducted and higher scores indicate greater fear, and the D-FISQ total score extends from 0 to 45 [

15,

16,

17]. A score of ≥6 is considered a positive fear of injection. The fifth section assessed the barriers to insulin administration, which was divided into two main sections: sociocultural factors and insulin-related factors. A five-point Likert scale (5: strongly agree, 4: agree, 3: neutral, 2: disagree, and 1: strongly disagree) was used to record the participants' perceptions toward barriers to insulin administration. The last section assessed adherence to insulin using the Lebanese Medication Adherence Scale-14. This scale covers the occupational, psychological, annoyance, and economic domains; it was utilized among Lebanese patients with non-communicable diseases [

18]. The dichotomous version of the LMAS-14 was used to make self-assessment simpler and less problematic, with questions rated 0 (Yes) and 1 (No), where lower scores would indicate higher adherence [

18]. The dichotomous format has some advantages, as it forces people to fall on one side of a scale or the other and is quicker to answer than questions that rely on a Likert scale, with no substantial loss of information, reliability, or validity.

2.4. Data Analysis

The completed surveys were extracted from Google Forms as an Excel sheet. Then the data was exported to Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 25.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY, USA: IBM Corp) for statistical analysis. The frequency and percentages were used for categorical variables, while the means and standard deviations were used for continuous variables. The normality of the fear of insulin injection and self-testing score was verified as the skewness and kurtosis values varied between ±1.96. Student T and ANOVA tests were used to compare two means and three or more means respectively. Pearson test was used to correlate two continuous variables. A linear regression was conducted afterward taking the fear of insulin injection and self-testing score as the dependent variables, and factors that showed a p < .25 in the bivariate analysis as independent ones. P < .05 was deemed statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

A total of 218 parents filled the survey. Their mean age of the parents was 39.61 ± 6.82 years. The mean age of their children with diabetes was 11.03 ± 3.69 years, with 48.6% females. Other details are summarized in

Table 1.

3.2. Experience of the Participating Person with Insulin

Out of the 218 respondents, 108 (49.5%) had experience (or any of their relatives/friends) with insulin use, with a mean of 5.7±5.6 experience years.

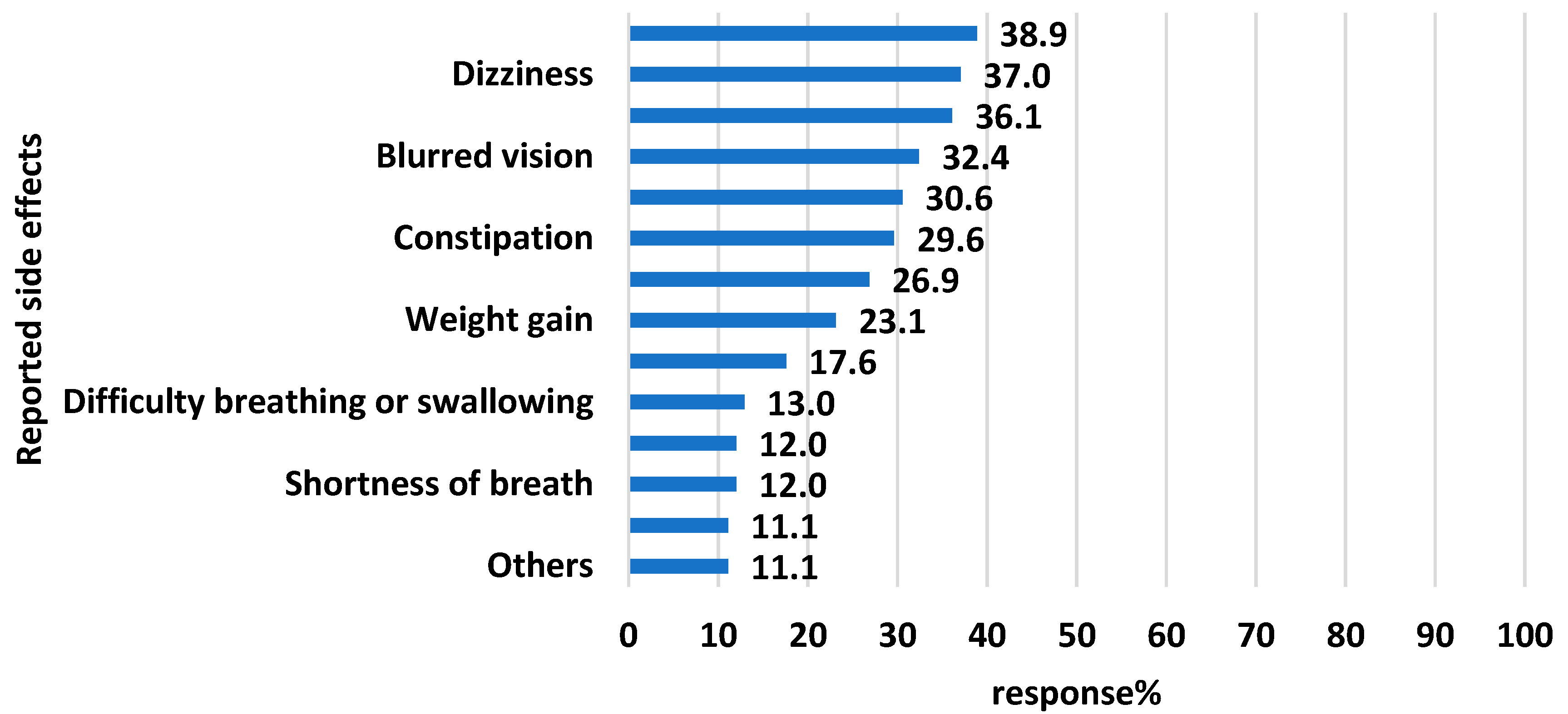

Figure 1 demonstrates the reported side effects of insulin experienced by the parents of their children with diabetes. More than one-third of the participants reported sweating, dizziness, local side effects at the injection site, blurred vision and general weakness.

3.3. Diabetes Fear of Self-Injecting Questionnaire:D-FISQ

Table 2 illustrates the responses to the D-FISQ items. The mean ±SD of the general fear score was 8.56±7.87 (out of 45). Such a score is considered positive clinical fear of injection; however, the score indicates a low level of fear (higher scores indicate greater fear). More than half of the responses to the D-FISQ items were either "almost never" or "sometimes", which contributes to the low score of fear.

3.4. Barriers to Insulin Administration, According to the Parents' Perception

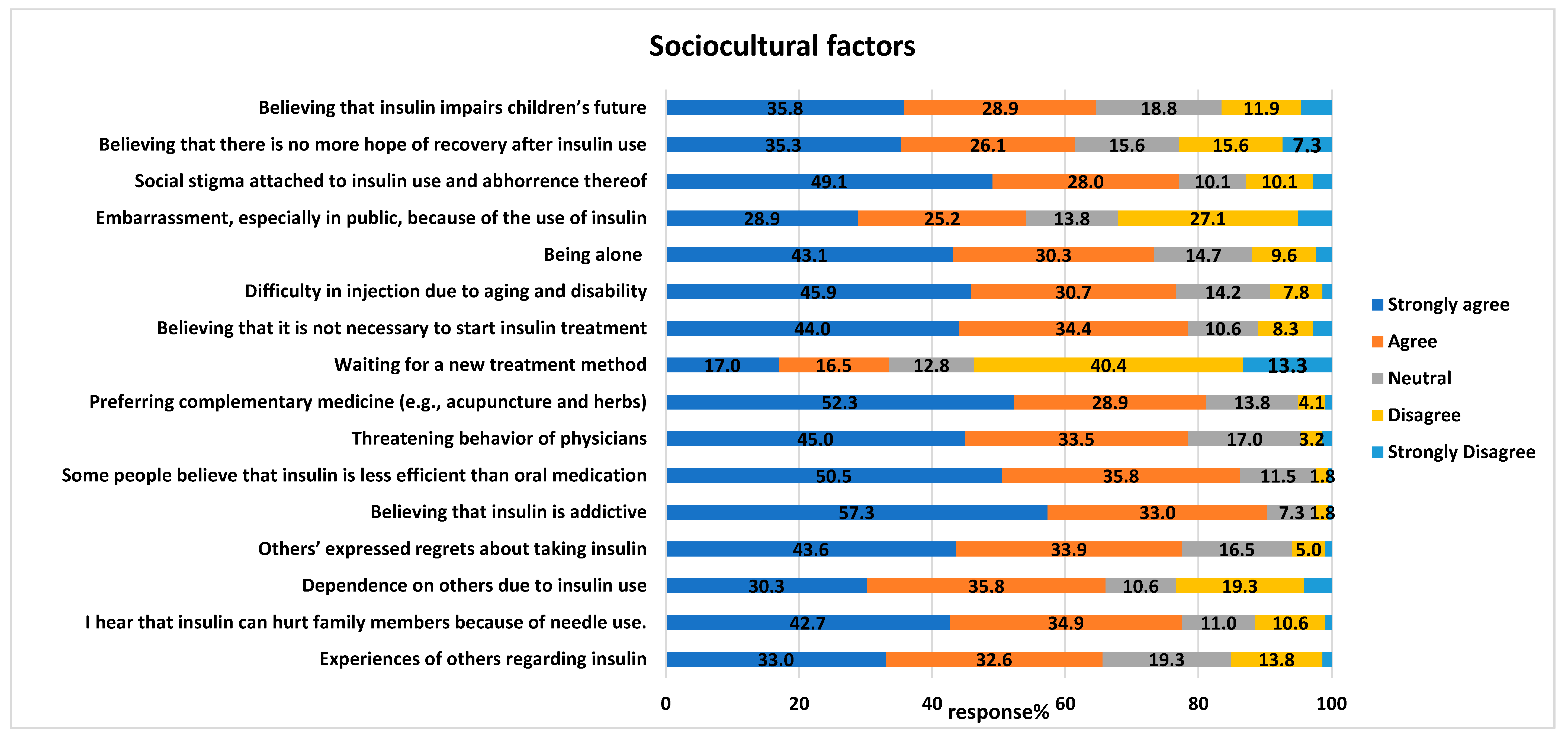

Most of the study participants agreed with various barriers to insulin administration, including sociocultural and insulin-related factors. Regarding the sociocultural factors, more than eighty percent of the parents believe (strongly agree/agree) that barriers to insulin administration could include the tendency for addiction to insulin (197, 90.4%), lower efficiency of insulin than oral medication (188, 86.8%) and preference for complementary medicine (e.g., acupuncture and herbs) over insulin (n=177, 81.2%), details in

Figure 2. In parallel, more than half of the parents strongly disagree/disagree that "waiting for a new treatment method" is a barrier to insulin administration (177, 53.7%).

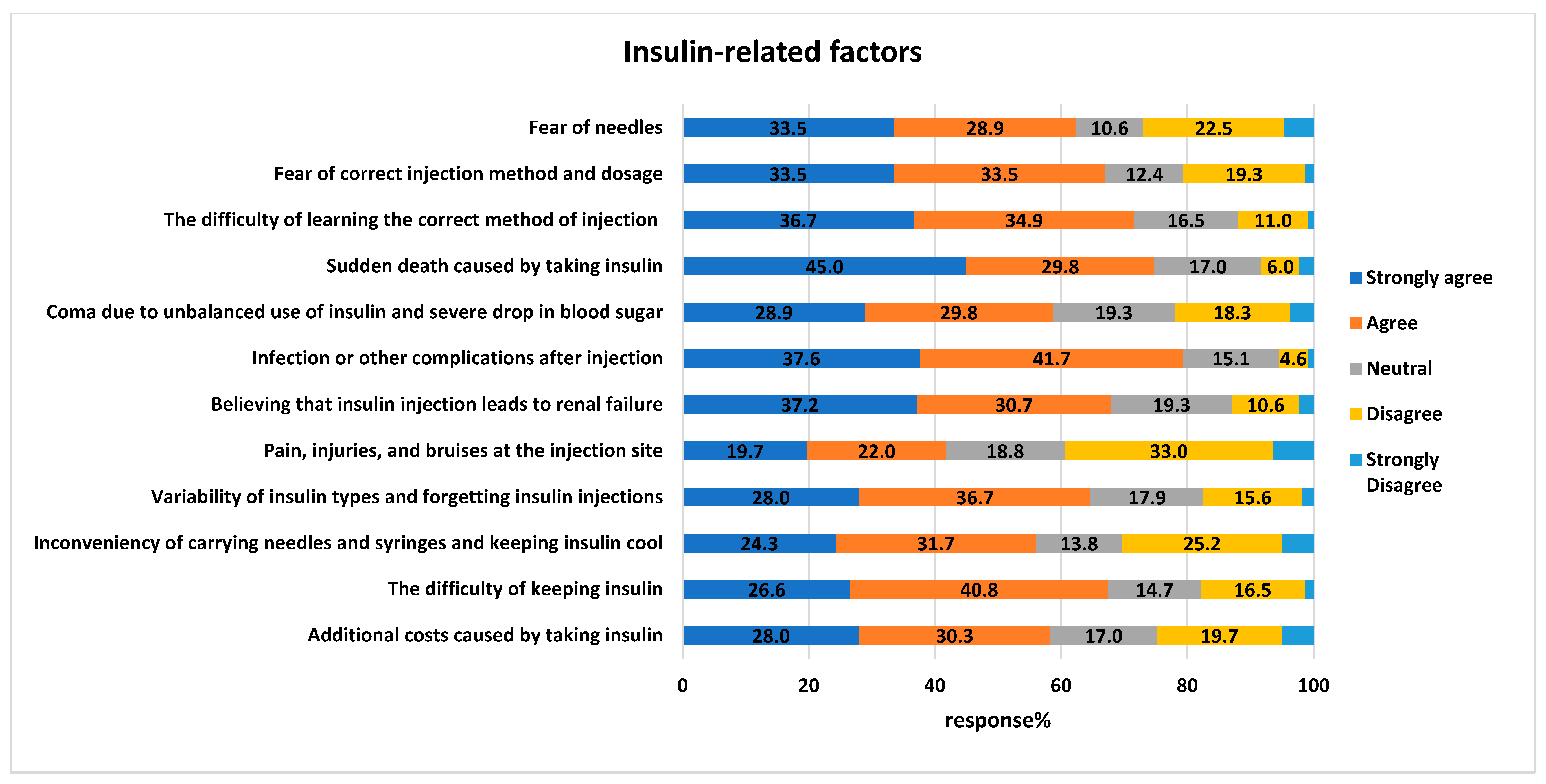

Regarding insulin-related factors, more than two-thirds of the participants agreed

/strongly agreed that the barriers include complications after injections, such as infections (173, 79.4%) and sudden death (163, 74.8%),

Figure 3. In addition, the difficulty of learning the correct injection method could be a barrier to administration (156, 71.6%). While more than half were either neutral or disagreed

/strongly disagreed (127, 58.3%) that “pain, injuries, and bruises at the injection site” could interfere with insulin administration.

3.5. Adherence to Insulin Using Lebanese Medication Adherence Scale (LMAS)

Table 3 demonstrates the participants' responses regarding adherence to insulin administration using the LMAS tool. The total adherence score was (13.06±1.62) out of 14, and higher scores indicated lower adherence levels. Most of the participants (more than 95%) declared their ability to stop insulin for the diabetic kid for many occupational. Psychological, annoyance and Economic factors.

3.6. Bivariate Analysis

The results of the bivariate analysis are summarized in

Table 4 and

Table 5. Having more sociocultural barriers and insulin-related barriers were significantly associated with more fear of insulin injection and self-testing, whereas an older age of the child and of the parent are associated with less fear of insulin injection and self-testing.

3.7. Multivariable Analysis

The results of the linear regression showed that more insulin-related barriers (Beta= 0.31) were significantly associated with more fear of insulin injection and self-testing, whereas an older age of the child (Beta= -0.44) was significantly associated with less fear of insulin injection and self-testing (

Table 6).

4. Discussion

There are various factors that contribute to patient’s fear and barriers to insulin injection administration such as sociodemographic and psychological factors, patient knowledge, as well as therapy-related factors. In this study, we distinguished the common barriers faced by individuals with diabetes. Our results showed that the most common factors that contributed to individuals with diabetes's fear of insulin therapy were age and insulin-related barriers.

Our study showed that older aged children had less fear of insulin injection and self-testing compared to young age consistent with the findings from a previous study [

19]. Most of the studies we reviewed presented an association of fear among children with diabetes without firm determinations of the reasons behind the fear of insulin/injection. The reasons for lower fear in advanced age can be interpreted by the fact that older children with diabetes will be on insulin for a longer time and are familiar with the procedure. Furthermore, older children have more intellectual development and reasoning which aids in better comprehension for the necessity and benefits of insulin injections. In addition, older children are more self-dependent with greater autonomy and responsibility and achieve an important role in their self-treatment and administer their own injections. According to another study, older children exhibit more coping strategies to manage their pain or discomfort during injections manifested by relaxation techniques compared to young, aged children.

Our study showed that more insulin-related barriers was linked with more fear of insulin injection and self-testing consistent with the results of another study [

20]. Our results can be interpreted by the fact that the most prominent reasons for refusal of insulin injections were self-injection stigmatization, the need to be compliant with the treatment plans, concerns about following healthy life-styles measures and finally, the perception that insulin injection means that patients reached the end-stage in the disease course [

21]. Other barriers highly associated with discouragement from the use of insulin injections were fear from the following side effects as weight gain, hypoglycemia, and injection pain [

22].

Other barriers that contributed to fear of insulin injection is the phobia from injection which can be explained by various reasons [

23]. Insulin phobia arises from the fear of needles, injections, pain and side effects that may arise at the site of injection. The fear and anxiety from injections can cause psychological distress causing difficulty in insulin administration. The psychological distress arising from insulin phobia can further exacerbate the challenges associated with appropriate diabetes management as patients perceive their fear as a personal weakness [

6]. There are many studies that support the fact that phobia from insulin injections can cause patients to skip injections because of their fear. This approach stems from patients’ belief that they can manage their diabetes without insulin injection or that alternative treatments or lifestyle modifications are enough to treat their conditions which evades the injections [

10].

In our study, we found that both adherence to medications and phobia levels among participants were low, although previous literature supports that phobia to injection is associated with lower adherence [

23]. Our study did not find a significant correlation between these two factors, and mostly related to the lack of proper awareness and education about the medication adherence to insulin.

4.1. Clinical Implications

Our study highlights the factors associated with the fears toward insulin administration among diagnosed children with diabetes from the perspectives of their parents. Thus, changing behavioral goals and eliminating certain feelings are linked with the utilization of injections. Modifying patients’ negative attitude and poor perception about insulin injections is crucial to support patients and achieve optimal therapeutic outcomes. Educating parents about the benefits of insulin therapy and the proper way of administration is a cornerstone since it increases adherence to treatment and favors acceptance. This could be achieved through attending support groups consisting of insulin users together with teaching pills-only users how to deal with complications related to insulin use such as hypoglycemia and weight gain.

4.2. Limitations

This study has some limitations. Such kind of studies are subject for information bias (participants not answering honestly), selection bias (due to the snowball sampling technique used to recruit participants), and residual confounding bias (since not all factors were taken into consideration in this study). In addition, this was a quantitative study that enabled a larger sample, however qualitative or a mixed-method design could be more appropriate to explore barriers that might not have been reported previously or that are unique to the Jordanian community. Furthermore, this study is not a longitudinal study that assessed glycemic control correlated with fear of insulin injection, which is an interesting point for future research.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study indicate that individuals with diabetes have barriers associated with insulin injection. The most common reason for insulin therapy refusal in this study was young age and insulin-related barriers. Therefore, specialized educational interventions can help minimize barriers and improve patients’ outcomes. There is a need for more awareness in clinics, health centers, media, and even individual counseling. Insufficient knowledge of insulin implication can result in complications, adverse patient outcome, poor compliance to therapy, instability, and suboptimal glycemic control. Therefore, knowing and removing the barriers about insulin therapy can help adjust the cooperation of patients and acceptance of treatment. Finally, insulin therapy can improve the quality of life and well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Muna Barakat, Souheil Hallit, Sarah Ibrahim, Sara Feras Abuarab and Abeer Alassaf; Data curation, Muna Barakat, Souheil Hallit and Marah Al-Jamal; Formal analysis, Souheil Hallit; Investigation, Muna Barakat, Souheil Hallit, Diana Malaeb, Malik Sallam, Sarah Ibrahim and Abeer Alassaf; Methodology, Muna Barakat, Souheil Hallit, Diana Malaeb, Malik Sallam, Marah Al-Jamal, Sarah Ibrahim, Sara Feras Abuarab and Rasha Odeh; Project administration, Muna Barakat; Resources, Muna Barakat and Malik Sallam; Software, Muna Barakat, Souheil Hallit, Marah Al-Jamal and Sara Feras Abuarab; Supervision, Muna Barakat; Validation, Muna Barakat, Souheil Hallit and Malik Sallam; Visualization, Souheil Hallit and Malik Sallam; Writing – original draft, Muna Barakat, Souheil Hallit, Diana Malaeb and Marah Al-Jamal; Writing – review & editing, Muna Barakat, Souheil Hallit, Diana Malaeb, Malik Sallam, Marah Al-Jamal, Sarah Ibrahim, Sara Feras Abuarab, Rasha Odeh and Abeer Alassaf.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jordan University Hospital, Amman, Jordan (Approval number: 129/2023). An electronic informed consent was considered obtained from each participant when submitting the online form. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants and Applied Science private University for their continuous support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Whittemore, R.; Jaser, S.; Chao, A.; Jang, M.; Grey, M. Psychological experience of parents of children with type 1 diabetes: A systematic mixed-studies review. Diabetes Educ. 2012, 38, 562–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decoster, V.A. Challenges of type 2 diabetes and role of health care social work: A neglected area of practice. Health Soc. Work 2001, 26, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, S.R.; Dolan, L.M.; Henry, R.; Powers, S.W. Parental fear of hypoglycemia: Young children treated with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion. Pediatr. Diabetes 2007, 8, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oser, T.K.; Oser, S.M.; McGinley, E.L.; Stuckey, H.L. A novel approach to identifying barriers and facilitators in raising a child with type 1 diabetes: Qualitative analysis of caregiver blogs. JMIR Diabetes 2017, 2, e8966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, H.; Liu, L.; Bi, Y.; Li, X.; Kan, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, S.; Zou, Y.; Yuan, Y. Related factors associated with fear of hypoglycemia in parents of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes-A systematic review. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2022, 66, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, S.; Jena, B.N.; Yeravdekar, R. Emotional and psychological needs of people with diabetes. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 22, 696. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, C.J.; Ratcliffe, S.J.; Tuttle, A.; Dougherty, S.; Lipman, T.H. Needle anxiety in children with type 1 diabetes and their mothers. MCN Am. J. Matern. Child Nurs. 2011, 36, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, S.; Yelland, M.; Heathcote, K.; Ng, S.-K.; Wright, G. Fear of needles-nature and prevalence in general practice. Aust. Fam. Physician 2009, 38, 172–176. [Google Scholar]

- Deacon, B.; Abramowitz, J. Fear of needles and vasovagal reactions among phlebotomy patients. J. Anxiety Disord. 2006, 20, 946–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, I.; Mohsin, S.; Iftikhar, S.; Kazmi, T.; Nagi, L.F. Barriers to the early initiation of Insulin therapy among diabetic patients coming to diabetic clinics of tertiary care hospitals. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 35, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollema, E.D.; Snoek, F.J.; Pouwer, F.; Heine, R.J.; Van Der Ploeg, H.M. Diabetes Fear of Injecting and Self-Testing Questionnaire: A psychometric evaluation. Diabetes Care 2000, 23, 765–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafie Pour, M.; Sadeghiyeh, T.; Hadavi, M.; Besharati, M.; Bidaki, R. The barriers against initiating insulin therapy among patients with diabetes living in Yazd, Iran. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2019, 12, 1349–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Futaisi, A.; Alosali, M.; Al-Kazrooni, A.; Al-Qassabi, S.; Al-Gharabi, S.; Panchatcharam, S.; Al-Mahrezi, A.M. Assessing Barriers to Insulin Therapy among Omani Diabetic Patients Attending Three Main Diabetes Clinics in Muscat, Oman. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2022, 22, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bou Serhal, R.; Salameh, P.; Wakim, N.; Issa, C.; Kassem, B.; Abou Jaoude, L.; Saleh, N. A new Lebanese medication adherence scale: Validation in Lebanese hypertensive adults. Int. J. Hypertens. 2018, 2018, 3934296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snoek, F.; Mollema, E.; Heine, R.; Bouter, L.; Van der Ploeg, H. Development and validation of the diabetes fear of injecting and self-testing questionnaire (D-FISQ): First findings. Diabet. Med. 1997, 14, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremolada, M.; Cusinato, M.; Bonichini, S.; Fabris, A.; Gabrielli, C.; Moretti, C. Health-related quality of life, family conflicts and fear of injecting: Perception differences between preadolescents and adolescents with type 1 diabetes and their mothers. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, S.; Pinar, R. Psychometric evaluation of a Turkish version of the diabetes fear of self-injecting and self-testing questionnaire (D-FISQ). Asian Nurs. Res. 2016, 10, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaeb, D.; Sacre, H.; Mansour, S.; Haddad, C.; Sarray El Dine, A.; Fleihan, T.; Hallit, S.; Salameh, P.; Hosseini, H. Assessment of medication adherence among Lebanese adult patients with non-communicable diseases during COVID-19 lockdown: A cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1145016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orenius, T.; LicPsych; Säilä, H. ; Mikola, K.; Ristolainen, L. Fear of injections and needle phobia among children and adolescents: An overview of psychological, behavioral, and contextual factors. SAGE Open Nurs. 2018, 4, 2377960818759442. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, A.; Mostafa, A.; Areej, A.; Mona, A.-m.; Shimaa, A.; Najd, A.-G.; Futoon, A. The perceived barriers to insulin therapy among type 2 diabetic patients. Afr. Health Sci. 2019, 19, 1638–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafie Pour, M.; Sadeghiyeh, T.; Hadavi, M.; Besharati, M.; Bidaki, R. The barriers against initiating insulin therapy among patients with diabetes living in Yazd, Iran. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2019, 12, 1349–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosomura, N.; Malmasi, S.; Timerman, D.; Lei, V.; Zhang, H.; Chang, L.; Turchin, A. Decline of insulin therapy and delays in insulin initiation in people with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus. Diabet. Med. 2017, 34, 1599–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, A.Z.; Qiu, Y.; Radican, L. Impact of fear of insulin or fear of injection on treatment outcomes of patients with diabetes. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2009, 25, 1413–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).