1. Introduction

In 2020, lung cancer was the second most diagnosed cancer in the whole world, counting 2,2 millions of new cases; in the same year it caused the major amount of deaths for tumor causes, counting 1,8 millions of deaths[

1,

2]. Non-small Cell Lung cancer (NSCLC) corresponds to 85% of lung tumors, and despite efforts to achieve appropriate lung screening, the stage at which patients reach diagnosis is often an advanced stage: only in 20% of cases are detected at stages I and II, while 30% are stage III and 50% stage IV[

3]. Surgery is actually the primary treatment modality among early-stage NSCLC, as well as resectable stage IIIA NSCLC[

4,

5]. Multiple randomized trials have shown survival benefit with the use of adjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy after surgical resection for early stage lung cancer (stage IB-IIIA) [

6,

7]. Patients with stage IIIA NSCLC with clinically evident N2 have a 5-year OS of only 10-15%, although this drops to 5% in those with bulky N2 involvement. Therefore, the treatment of stages IIIA also remains controversial. Treatment with multimodal approach of N2-NSCLC, based on the use of chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy, has been shown to be related to a better Overall Survival (OS) and Disease-Free Survival (DFS) [

8,

9]. The real benefit of induction therapy has not been demonstrated to date[

9], however its clinical use is widely accepted, with the aim of obtaining tumor downstaging, increasing surgical resectability, and improving DFS thanks to the supposed action on lymph nodes or distant micrometastases [

10]. A meta-analysis demonstrated that in neoadjuvant treatment, the addition of radiotherapy to chemotherapy did not increase survival, therefore since no phase III trial demonstrated a significant survival benefit using induction chemoradiotherapy compared to chemotherapy alone, the latter is the preferred option, due to fewer collateral effects. Nowadays, the activation of the human immune system to fight NSCLC, by blocking inhibitory immune checkpoints, has gained attention. Several phase III trials have confirmed the role of the immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) pembrolizumab, as a standard first-line treatment for patients with locally-advanced or metastatic NSCLC [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Especially, compared with monotherapy, chemotherapy based on ICIs plus platinum resulted in significantly better OS and PFS regardless of PD-L1 expression [

15,

16,

17]. The treatment with nivolumab plus platinum-doublet chemotherapy was first added to the guidelines as neoadjuvant systemic therapy. The preliminary efficacy of chemoimmunotherapy in NSCLC patients is being widely discussed and has prompted research worldwide[

18,

19,

20,

21].The aim of this retrospective study is to evaluate the predictive factors of response to induction chemotherapy, in patients with resectable NSCLC, operated at the Department of Thoracic Surgery of the Siena University Hospital from 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2020. Almost all the patients were discussed in the three GOMs (Multidisciplinary Oncological Groups) of the South-East Tuscany Vast Area.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective study included all patients who underwent pulmonary resection surgery , after receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy, between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2020 at the Department of Thoracic Surgery of Siena University Hospital. After review of histological examinations and with the help of both AOUS (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Senese) and community oncology colleagues, 78 patients were included in the study.

The patients included in the study were mainly citizens of the provinces of Siena, Arezzo and Grosseto (USL Toscana Sud-Est): 43 patients in the province of Siena, 22 patients in the province of Arezzo, and 13 patients in the province of Grosseto. The average age of patients was 65 years old with a median of 66 years old. As regards gender, 25 were female and 53 were male. Pre-treatment evaluation included patient clinical history, physical examination, lung function tests, complete blood chemistry, total body computed tomography (CT) scan with intravenous contrast material, 18F-fuorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography integrated with computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) and bronchoscopy. Patients included in the study had diagnosis of NSCLC based on endo-bronchial biopsy or CT-guided fine-needle aspiration; at the time of diagnosis, stages varies beetween stage IIB-IV. Mediastinal invasive staging via endoscopic biopsy with endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) or mediastinoscopy was considered in patients with preoperative suspected N2 disease, defined as both mediastinal nodal enlargement (short-axis diameter: > 1 cm) on CT and an abnormal 18F-fuorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake on PET/CT. The tumors’ histological types and their immunohistochemistry are listed in

Table 1. The 3 patients with stage IV disease at diagnosis were treated with stereotactic radiotherapy or surgical removal of a single brain metastasis and subsequently underwent lung surgery. The 5 patients with stage IIIB at diagnosis had a cT4N2 disease.

Following the histological diagnosis, patients underwent different induction therapy schemes: 53 patients received platinum and gemcitabine-based chemotherapy; 12 patients received platinum and pemetrexed chemotherapy; 4 patients received chemotherapy based on Cisplatin and Etoposide; 1 received pemetrexed-based chemotherapy alone; 3 patients received chemotherapy based on Cisplatin, Etoposide and Bevacizumab; 1 received carboplatin-only chemotherapy; 3 patients received chemotherapy based on Cisplatin and Vinorelbine; 1 received pembrolizumab-only chemotherapy. (

Table 1)

Following induction therapy, the patients were restaged by performing a new total body CT and PET-CT, as shown in

Table 2.

The postoperative surveillance comprised: physical examination, chest-CT scan and upper abdominal ultrasound examination or total-body CT scan performed every three months for the first two years after surgery, and at 6-month intervals thereafter.

We analyzed the regression rate of primary tumor based on the size reduction of the lesion, and the regression of N2 and N1 nodal involvement, based on reduced short-axis diameter on CT and on the reduction or absence of abnormal 18F-fuorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake on PET/CT; the results are shown in

Table 3.

Retrospective data were analyzed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) program for iOS by the Kaplan-Meier method, and survivals were compared by Log-rank test. We analyzed survival on the basis of: neoplastic estimated regression rate, patient age, N2 parameter regression after induction chemotherapy, post-chemotherapy stage, type of induction chemotherapy.

3. Results

From 1st January 2013 to 31st December 2020, 78 patients underwent induction chemotherapy and subsequently were operated in the Unit of Thoracic Surgery of the Siena University Hospital, with an average age of 65 years and a median of 66 years. Among these patients, 4 received a complete pneumonectomy (5.1%) while the remaining 74 received a lobectomy (94.9%). Patients had an overall-survival (OS) of 58% at 5 years.

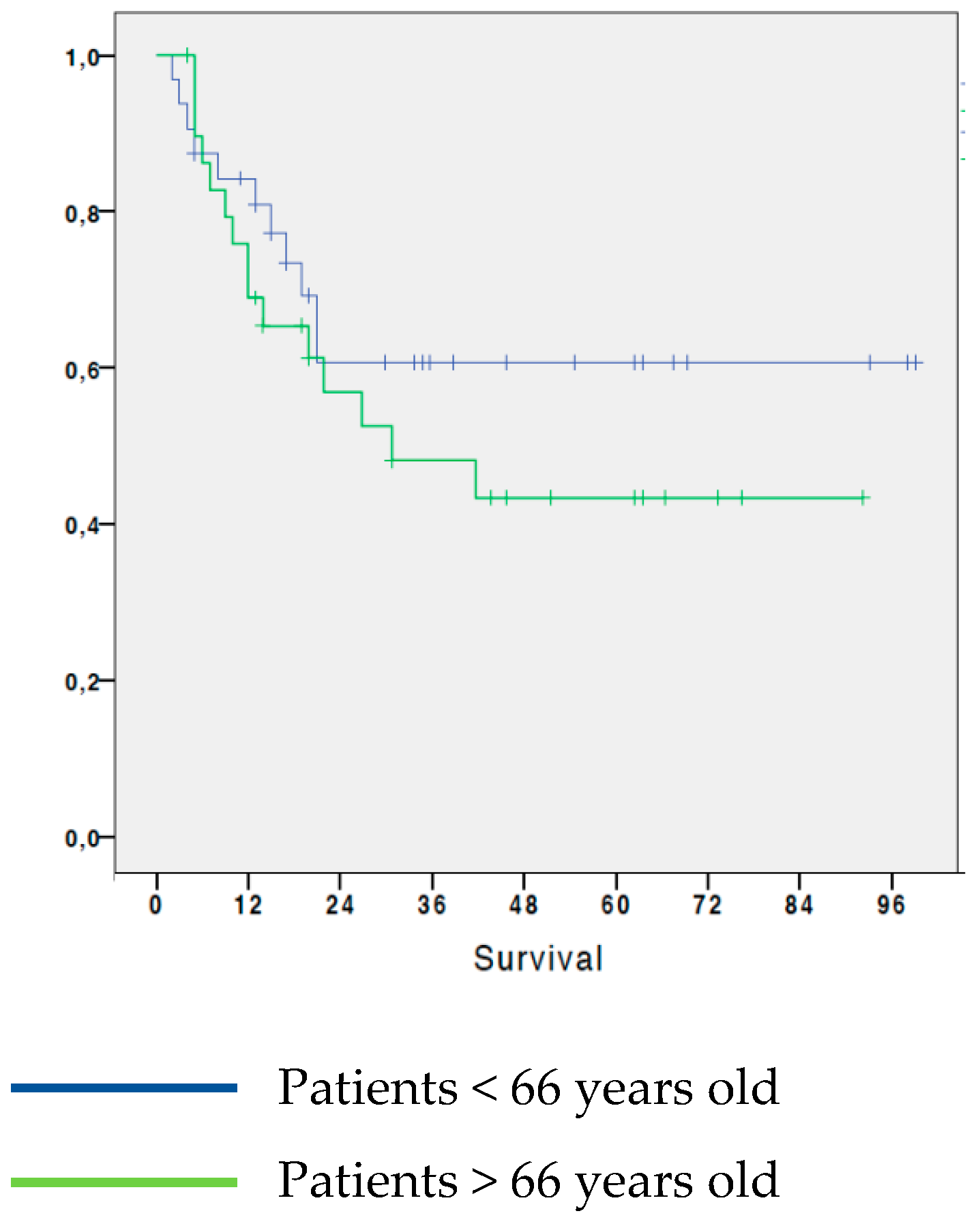

3.1. Analysis of survival in NSCLC patients by age

Regarding the age of the patients, the 5-year OS of patients younger than 66 years old at the time of surgery was 60.6%, while in patients aged 66 or over, the 5-year survival was 43.3%. This initial analysis shows that patients aged less than 66 years at the time of surgery had a slightly greater 5-year OS than patients aged 66 or older, although the difference was not significant (0.451). (

Figure 1).

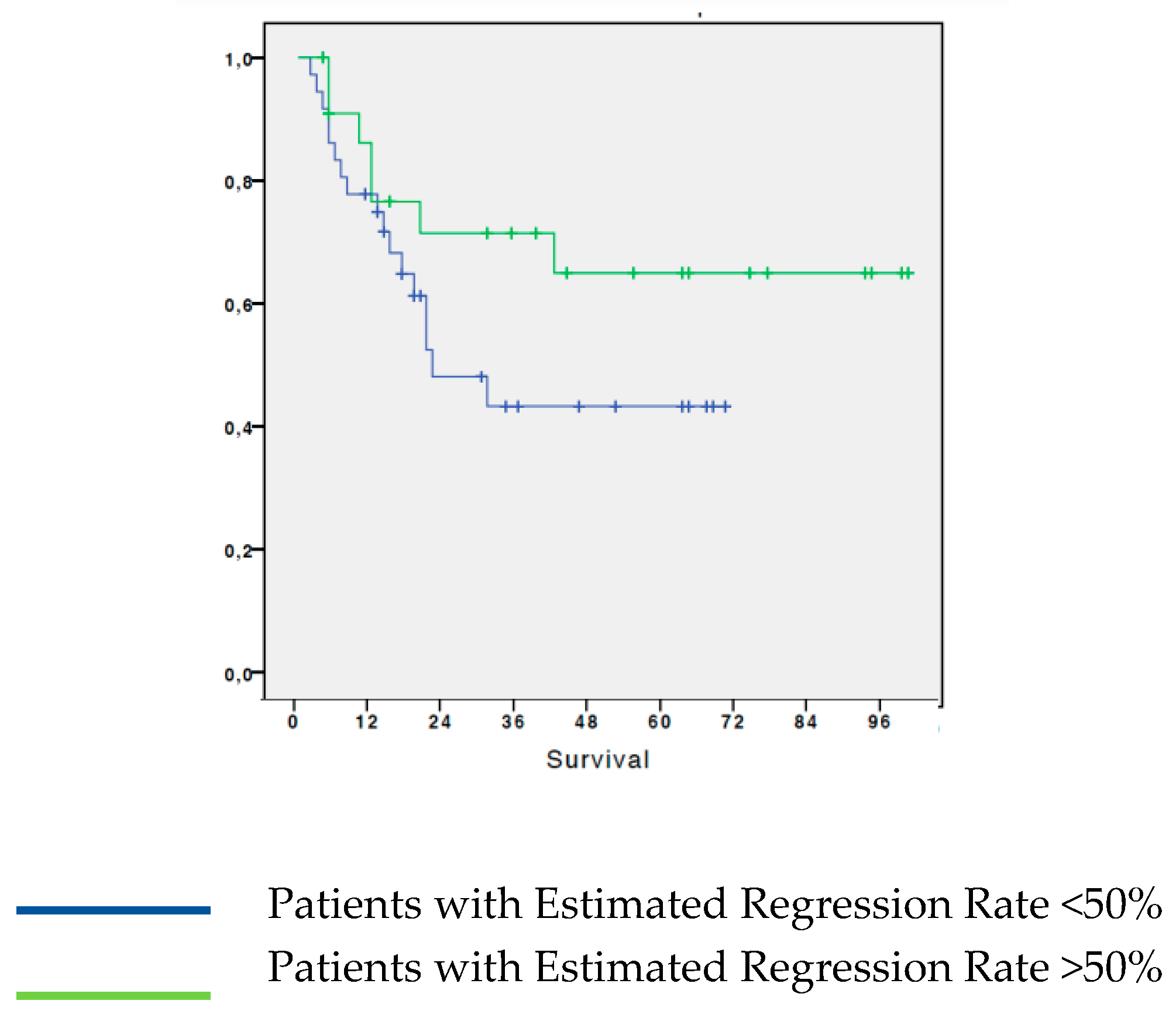

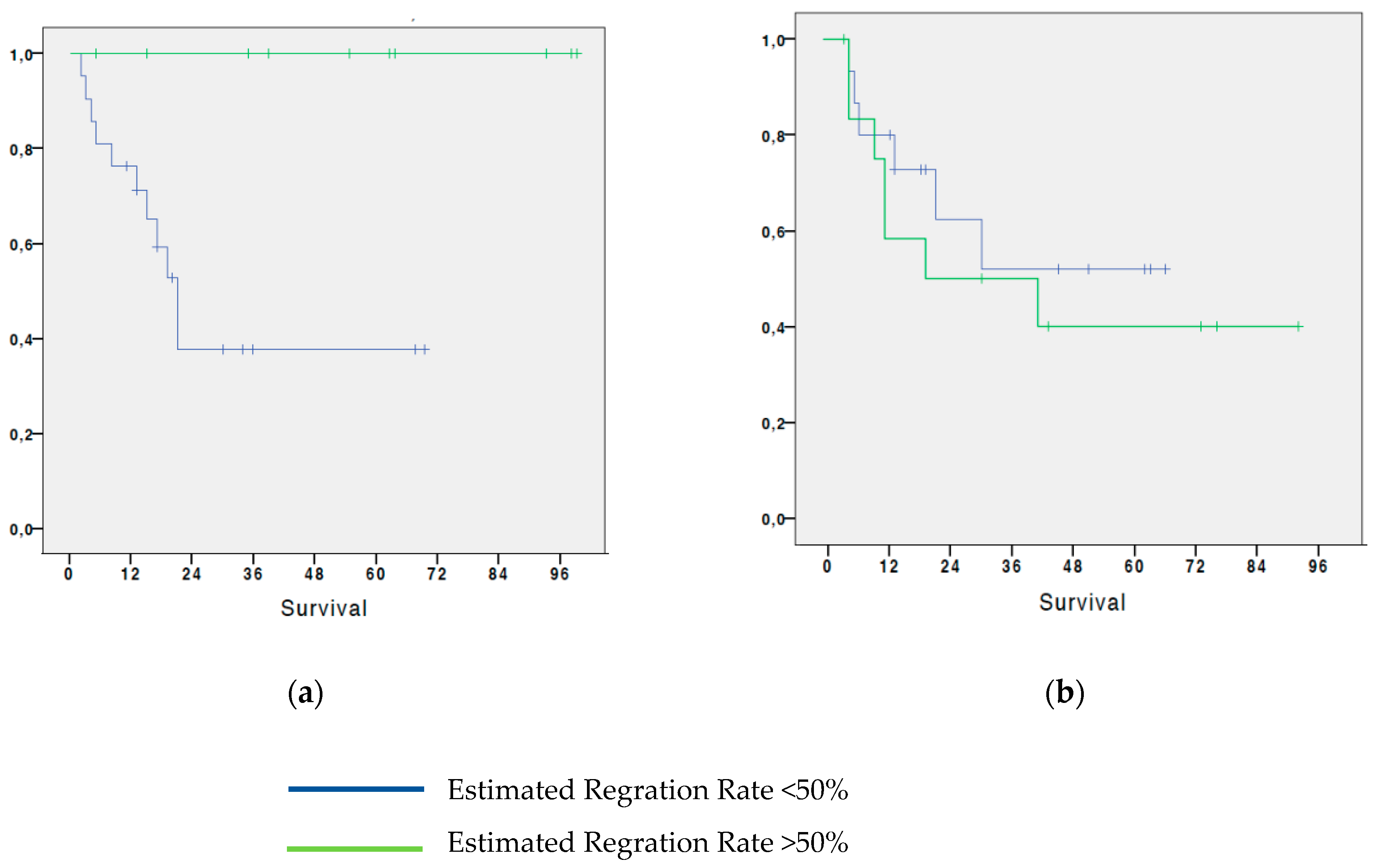

3.2. Analysis of survival in patients with NSCLC based on the estimated regression by histological test

We analyzed survival based on disease regression estimation according to histological examination. From the analysis it resulted that patients who had an estimated T-regression greater than 50% have a 65% 5-year OS; while patients who had a less than 50% estimated regression, showed a 5-year OS of 43.3%. The difference between the two groups, although evident, did not reach statistical significance (p=0.147). (

Figure 2).

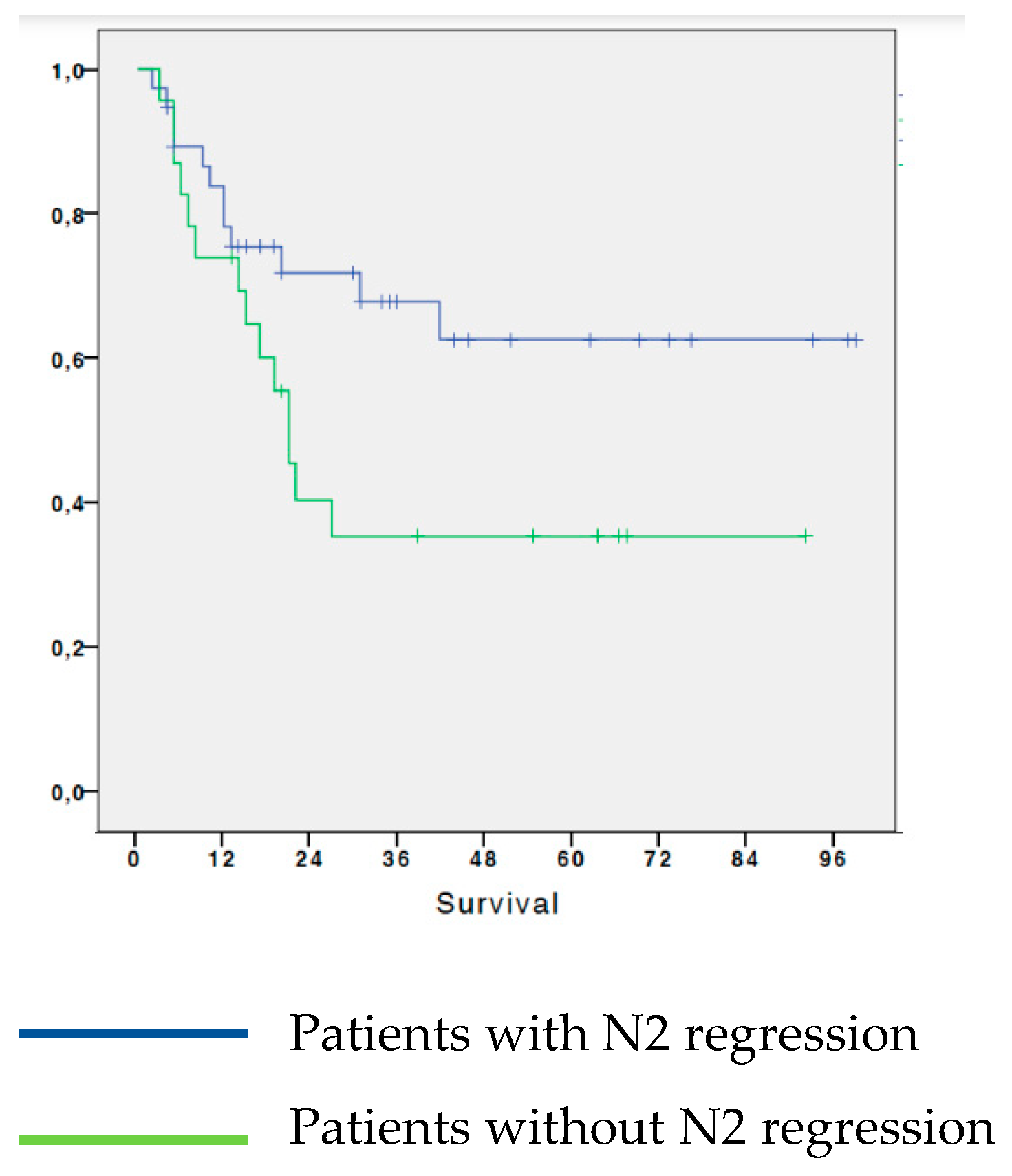

3.3. Analysis of survival in patients with NSCLC based on N2 regression

We analyzed survival according to regression of the N2 parameter after chemotherapy. The 5-year OS of patients who had a regression of N2 parameter following neoadjuvant chemotherapy was 62.6%; while the patients who did not have N2 regression following induction chemotherapy had a 5-year OS of 35.5%. The survival difference between the two groups was statistically significant (p=0.031). (

Figure 3)

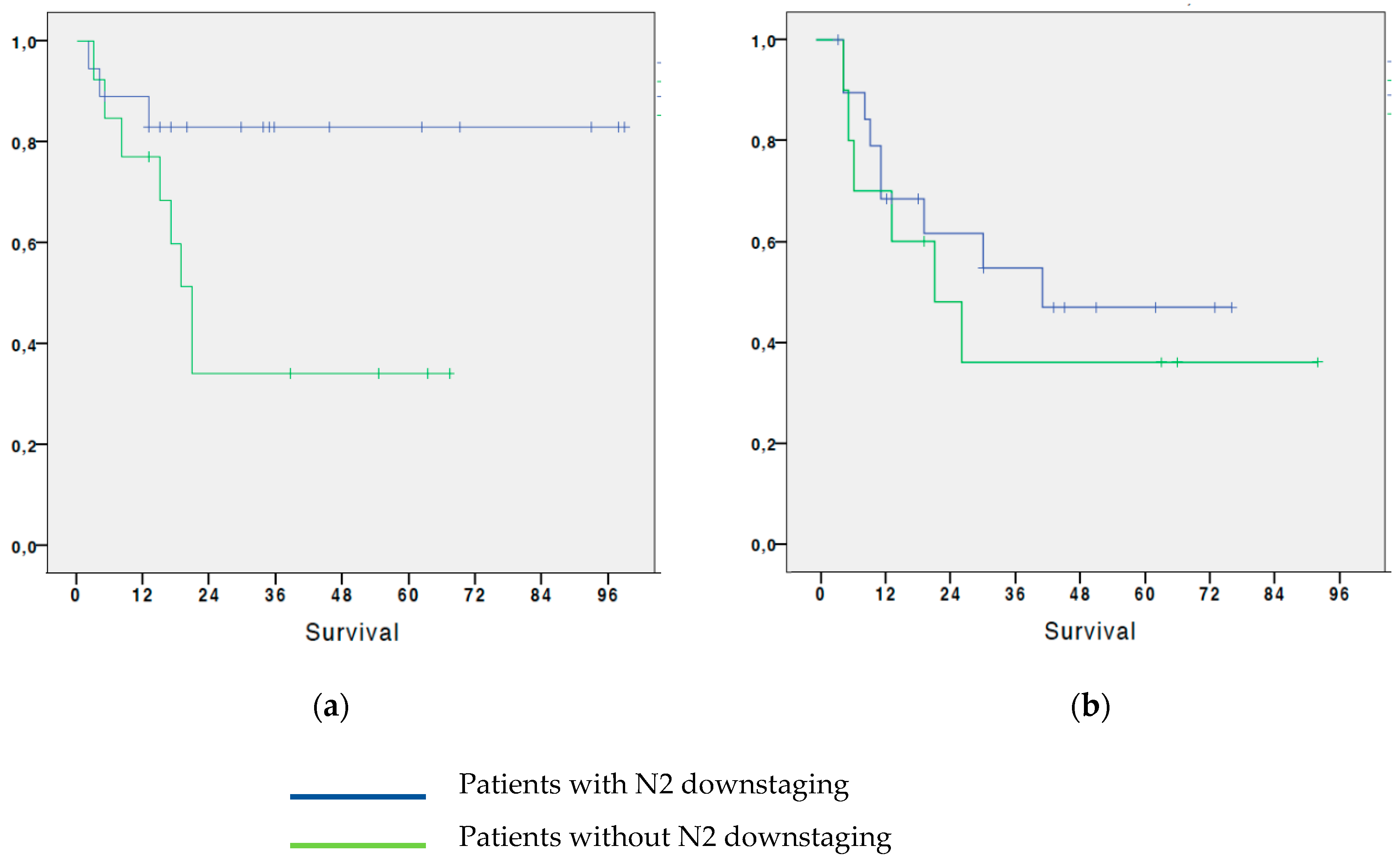

3.4. Analysis of survival in patients with NSCLC based on the regression of N2: subdivision by age subgroups

We also tried to find the association between OS and regression of the N2 parameter, dividing the patients into two groups: a first group (A) containing patients younger than 66 years old (36 patients), and a second group (B) containing patients older than or equal to 66 years old at the time of surgery (42 patients). The analysis shows that:

In Group A, patients who had N2 downstaging after neoadjuvant chemotherapy had a 5-year OS of 83%, while in patients who did not have a regression of the N2 parameter after induction CT was 34.2%. The difference was statistically significant (p=0.019)

In Group B, patients who had N2 parameter regression after neoadjuvant CT had a 5-year OS of 46.9%; while the 5-year OS in patients who did not have a regression of the N2 parameter after induction CT was 36% (

Figure 4). The difference was not significant (p=0.321). (

Figure 4).

3.5. Analysis of survival in patients with NSCLC based on the estimate of histological regression: subdivision by age groups (A: under 66 years-old; B: over 66 years-old)

Finally, we analyzed the association between survival and the estimated regression according to histological examination, dividing the patients into the same two previous groups (A and B). The analysis shows that:

4. Discussion

Locally advanced NSCLC is a very heterogeneous disease, which includes tumors that are bulky, or tumors that invade adjacent structures, or with lymph node metastases, without distant metastases. The curative treatment of this stage is multimodal: several therapeutic options are now available, although a therapeutic standard has not yet been reached. Although 5-year OS at this stage is still poor, it has been observed that compared to surgery alone, neoadjuvant or adjuvant systemic treatment for resectable tumors increases OS by approximately 5% at 5 years[

22]. Although the benefit of perioperative chemotherapy has been demonstrated for patients with resectable stage III NSCLC, only a small proportion of these patients are candidates for radical surgery. In these patients, 5-year OS depends primarily on the size of the tumor and on the extent of lymph node involvement [

23,

24].In the absence of prospective randomized studies comparing neoadjuvant treatment followed by surgery with upfront surgery with adjuvant systemic treatment, to date both therapeutic options are considered valid. In the study by Andre et al.[

25] it was found that in patients with stage IIIA-N2 who underwent surgery, several factors were related to a worse prognosis, including clinical stage cN2, multilevel lymph node involvement, pathological stage pT3 or pT4, and the absence of induction chemotherapy. At our center all patients with disease stage greater than or equal to IIA (T1-2N1) underwent neoadjuvant treatment. We analyzed the 5-year OS by dividing the population by age (over or under 66 years-old), but the difference in OS was not significant between the two groups. We subsequently evaluated the difference in OS between patients with Tumor regression > 50%, compared to those with regression <50%, and this also was found to be non-significant, as observed in several meta-analysis. [

26] Despite this, we found that the difference in 5 years-OS between patients with regression of the N2 was significant compared to those without regression. This result could confirm that very different tumor entities exist within locally advanced NSCLC, with a poorer prognosis in patients with N2 lymph node disease. From these results, stage IIIA-N2 appears to obtain a prognostic advantage if subjected to inductive systemic treatment if associated with the regression of N2, and therefore it would seem mandatory to treat these patients, as those who respond to the treatment would obtain a survival advantage. However, by grouping patients with N2 downstaging by age, it emerged that the survival advantage was only observed in patients under 66 years old. This can be justified by the fact that an inductive treatment causes the patient numerous side effects, which a young patient can tolerate better than an older patient. The same conclusion can be assumed from the result obtained by comparing the 5-year OS in patients with estimated pathological regression > 50%, divided into the two groups by age: the advantage is observed only in patients aged less than 66 years-old, therefore it cannot be observes an advantage in performing neoadjuvant treatment in older patients. The importance of age observed in our experience was also observed by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center study [

27]. In older patients, upfront surgery would allow avoiding the potential disadvantages of induction chemotherapy, such as toxicity, risk of progression and perioperative complications. In these patients an adjuvant treatment following surgery may be desirable, as suggested by Lim's meta-analysis in which no significant difference is observed between pre- and post-surgery chemotherapy[

28].

In conclusion, our data confirm that induction chemotherapy remains a valid therapeutic option in patients with locally advanced and resectable NSCLC, with 5-year survival rates around 40-50%[

29]. In our study the 5-year OS stands at 58%; compared to other studies[

30], this very positive result reflects the fact that within our sample there are also stages IIB, not just IIIA, which in fact have a longer survival compared to more advanced stages. These survivals reflect the adequate patient selection by multidisciplinary teams, both in the pre-induction phase and in the evaluation of the chemotherapy response. Although excellent results of combined chemo-radiotherapy followed by immunotherapy in locally advanced unresectable patients are described, nevertheless, as we demonstrated with our study, a considerable proportion of resectable patients treated with induction chemotherapy are free from disease at 5 years. Both the type of chemotherapy and intervention did not show an impact on survival, while both the percentage of disease regression and the lymph node down-staging of the N2 stations have great value. The association of these two parameters with age selects a group of patients with a high expectation of healing at 5 years, although the age cut-off was identified on the basis of the median age of the sample.

The limitations of this study are its monocentric and retrospective nature. Furthermore, patients with different initial stages of disease were included in this study, which may create a bias in the results. Finally, both the degree of regression and lymph node down-staging are parameters that have postoperative prognostic value, therefore we cannot use these parameters to discern which patients to undergo induction chemotherapy and which ones to allocate to upfront surgery.

The next objective of our study is to analyze the pre- and post-chemotherapy CT-scan and PET-imaging in the sample in question in order to be able to search, with radiologist colleagues, for any predictive signs of response and down-staging in order to offer surgery only to those patients who benefit most from surgical treatment and to send patients who, although resectable, still have a worse prognosis, to chemo-radio-immune therapy. It has in fact been observed that the reduction in 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake on PET-CT after neoadjuvant treatment is a positive prognostic factor for long-term survival.[

31,

32]

5. Conclusions

The treatment of locally advanced NSCLC is multimodal; although various therapeutic schemes are available, neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical surgery can currently guarantee a satisfactory 5-year OS. The percentage of disease regression and the lymph node down-staging of the N2 stations have great value on the outcomes, although this advantage seems to be observed mostly in younger patients. Great importance lies in the multidisciplinary oncologic discussion of clinical cases, which could provide support in the careful selection of the ideal patients to undergo neoadjuvant treatment, i.e. one in whom the response to pre-surgical systemic treatment also translates into an increase in overall survival or advantages in terms of outcomes.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, C. Catelli and L. Luzzi; methodology, T. Ligabue; software, P. Paladini; validation, C. Catelli, N. Sarnicola, and L. Luzzi; formal analysis, F. Bloise; investigation, L. Luzzi; resources, F. Bloise, C. Bengala data curation, N. Sarnicola; writing—original draft preparation, C. Catelli; writing—review and editing, C. Catelli, L. Luzzi; visualization, C. Catelli; supervision, L. Luzzi; project administration, C. Catelli; funding acquisition, L. Luzzi. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to patients’ privacy policy.

Acknowledgments

Administrative and technicalsupport was given by the Group Multidisciplinary Oncological Groups of Arezzo and Grosseto (Dr. Sabrina Giusti, Dr. Francesco Melandri, Dr. Roberto Dottori, Dr. Duccio Venezia).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sung, H.; et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. , “Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Koning, H.J.; et al. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Volume CT Screening in a Randomized Trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parekh, J.; Parikh, K.; Reuss, J.E.; Friedlaender, A.; Addeo, A. Current Approaches to Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy in Resectable Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2023, 25, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitzman, B.; Varghese, T.K.J.; Kuchta, K.; Krantz, S.B. National guideline concordance and outcomes for pathologic N2 disease in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Dis. 2022, 14, 1360–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunant, A.; Pignon, J.-P.; Le Chevalier, T. Adjuvant chemotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer: contribution of the International Adjuvant Lung Trial. Clin. cancer Res. an Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2005, 113 Pt 2, 5017s–5021s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douillard, J.-Y.; et al. Adjuvant vinorelbine plus cisplatin versus observation in patients with completely resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (Adjuvant Navelbine International Trialist Association [ANITA]): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. Oncol. 2006, 7, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campisi, A.; et al. Upfront surgery for N2 NSCLC: a large retrospective multicenter cohort study. Gen. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Song, W.-A.; et al. Survival benefit of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: an updated meta-analysis of 13 randomized control trials. J. Thorac. Oncol. Off. Publ. Int. Assoc. Study Lung Cancer 2010, 5, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decaluwé, H.; et al. Surgical multimodality treatment for baseline resectable stage IIIA-N2 non-small cell lung cancer. Degree of mediastinal lymph node involvement and impact on survival. Eur. J. cardio-thoracic Surg. Off. J. Eur. Assoc. Cardio-thoracic Surg 2009, 36, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; et al. Advances in efficacy prediction and monitoring of neoadjuvant immunotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1145128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, T.S.K.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously untreated, PD-L1-expressing, locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-042): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet (London, England) 2019, 3930183, 1819–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garassino, M.C.; et al. Patient-reported outcomes following pembrolizumab or placebo plus pemetrexed and platinum in patients with previously untreated, metastatic, non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-189): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. Oncol. 2020, 21, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Ares, L.; et al. A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Pembrolizumab Plus Chemotherapy in Patients With Metastatic Squamous NSCLC: Protocol-Specified Final Analysis of KEYNOTE-407. J. Thorac. Oncol. Off. Publ. Int. Assoc. Study Lung Cancer 2020, 150, 1657–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, L.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 3782, 2078–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paz-Ares, L.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy for Squamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 3791, 2040–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; et al. The landscape of immune checkpoint inhibitor plus chemotherapy versus immunotherapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 4913–4927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.-H.; et al. Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant immunotherapy in resectable nonsmall cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis. Lung Cancer 2020, 147, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Gao, Y.; Xue, Q.; Gao, S.; He, J. Safety and Efficacy of Neoadjuvant Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy in Patients with Resectable Non-small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review. Targeted oncology 2021, 16, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulas, E.B.; Dickhoff, C.; Schneiders, F.L.; Senan, S.; Bahce, I. , “Neoadjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitors in resectable non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review. ESMO open 2021, 6, 100244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; et al. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl. lung cancer Res. 2022, 11, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis using updated data on individual patients from 52 randomised clinical trials. Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Collaborative Group. BMJ 1995, 311010, 899–909.

- Roth, J.A.; et al. A randomized trial comparing perioperative chemotherapy and surgery with surgery alone in resectable stage IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1994, 86, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosell, R.; et al. A randomized trial comparing preoperative chemotherapy plus surgery with surgery alone in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 330, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andre, F.; et al. Survival of patients with resected N2 non-small-cell lung cancer: evidence for a subclassification and implications. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2000, 186, 2981–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preoperative chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet (London, England) 2014, 383928, 1561–1571. [CrossRef]

- Martini, N. Mediastinal lymph node dissection for lung cancer. The Memorial experience. Chest Surg. Clin. N. Am. 1995, 5, 189–203. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, E.; Harris, G.; Patel, A.; Adachi, I.; Edmonds, L.; Song, F. Preoperative versus postoperative chemotherapy in patients with resectable non-small cell lung cancer: systematic review and indirect comparison meta-analysis of randomized trials. J. Thorac. Oncol. Off. Publ. Int. Assoc. Study Lung Cancer 2009, 41, 1380–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicer, J.D.; et al. Multimodality Therapy for N2 Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: An Evolving Paradigm. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2019, 107, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.; et al. Long-term results of combined-modality therapy in resectable non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 1989–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöttgen, C.; et al. Standardized Uptake Decrease on [18F]-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Is a Prognostic Classifier for Long-Term Outcome After Multimodality Treatment: Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Trial for Resectable Stage IIIA/B Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 341, 2526–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtsuka, T.; et al. FDG-PET imaging for lymph node staging and pathologic tumor response after neoadjuvant treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Ann. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. Off. J. Assoc. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. Asia 2006, 12, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).