1. Introduction

The rapid advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) and its adoption for teaching and educational purposes could mark a new era of innovation in academia [

1,

2,

3]. The successful adoption of AI in higher education could pave the way for transformative changes with the potential to reshape the traditional pedagogical methods [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. One of the latest AI-based advancements is ChatGPT —a large language model (LLM) developed by OpenAI— which emerged as a paradigm-shifting innovation for acquisition of information [

10,

11,

12].

The LLMs have the potential to revolutionize teaching methodologies in higher education, particularly in fields like health care education [

1,

13,

14,

15]. While AI-based tools could present promising possibilities to reform the teaching and learning processes, these tools are also faced with skepticism and are a subject of ongoing debate due to multiple concerns including ethical issues, factual issues, risk of misinformation spread, copyright issues, among other valid concerns [

1,

16,

17,

18,

19].

Currently, several challenges are encountered by university students including the issues of rising costs, information overload, the continuous need to acquire and develop new skills, and the limited timeframes for achieving the intended learning outcomes [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Therefore, novel AI tools like ChatGPT can be valuable to encounter such challenges through increasing efficiency of the learning process with minimal costs and improve the acquisition of new skills by providing a personalized educational experience [

1,

14,

25,

26]. Consequently, the need to improve AI literacy among university students appear of paramount importance for competent, ethical, and responsible use of these tools [

27,

28].

On the other hand, valid concerns arise in light of the possible challenges of AI implementation in higher education including the prospect of overreliance on AI assistance which could be associated with compromising the critical thinking and reasoning and decline in the analytical capabilities [

1,

5,

18,

29]. This appears as a major issue considering the aim of higher education to enhance cognitive abilities, which could be compromised by excessive dependency on technological tools including the AI-based tools [

30,

31,

32].

Additionally, the quality of AI-generated information is another major concern considering the reported factual concerns associated with the use of AI-based tools including ChatGPT [

1,

19,

33]. Moreover, the quality of training datasets used in LLM development could result in the generation of biased content [

19,

34,

35]. Finally, the unequal accessibility to AI-based tools in various societies and regions, could deepen the inequity in education with subsequent psychological and socioecological issues [

36,

37,

38].

The successful integration and acceptance of innovative tools such as ChatGPT within educational settings can be influenced by a variety of factors among both the students and instructors [

39,

40,

41]. For example, an important factor precluding the use of ChatGPT can be the perception of possible risks (e.g., security risks, privacy concerns, unreliability of information, risk of accusation of plagiarism and violation of academic policies) [

1,

14,

42,

43]. Thus, the perceived risk of ChatGPT use can be a decisive factor for its adoption in the teaching and learning processes [

1,

18,

44,

45]. Another important factor is the perceived ease of use, which is an important factor driving the acceptance of this novel tool in education [

46].

Additionally, the perceived usefulness can be a significant driving factor in the adoption of ChatGPT in the learning process through facilitating academic activities and assignments while saving time [

47,

48,

49]. Furthermore, a complex array of cognitive and behavioral determinants as well as the perceived enjoyment, social influence and attitude towards technology in general can be viewed as important determinants for the acceptance of a novel technology such as ChatGPT [

50,

51,

52].

To unravel the multifaceted aspects driving the adoption of ChatGPT among university students for educational purposes, a recent study validated a survey instrument based on the technology acceptance model (TAM) [

53]. This instrument, termed “TAME-ChatGPT” (Technology Acceptance Model Edited to Assess ChatGPT Adoption) dissected a wide range of factors that could influence university students’ attitudes and behaviors towards ChatGPT and its usage [

48].

Therefore, the primary objective of the current study was to analyze the extent and determinants of ChatGPT usage among university students in Arab-speaking countries. The study aimed to provide deeper insights that can inform educators, policymakers, and academic institutions on the possibilities and concerns regarding ChatGPT integration within the academia. The study objectives included confirming the validity of TAME-ChatGPT survey instrument conceived to improve the understanding of the complex factors influencing the adoption of ChatGPT in educational settings from the students’ perspective.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The current study employed a cross-sectional design with an electronic distribution of a previously validated survey instrument [

48]. The sample was collected using a non-probability sampling (convenience-based approach). The survey was hosted in Google Forms and distributed by the authors from multiple Arab countries (Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and Tunisia). The cut-off for inclusion of participants in the sample per country was set at a minimum of 125 valid responses based on the number of items in the original TAME-ChatGPT scale (25 items) [

48]. A minimum sample size of 125 participants (5 participants per item) was considered essential to maintain the statistical rigor and ensure the robustness of the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results, which would allow an accurate estimation of model parameters and factor loadings [

54,

55].

The self-administered questionnaire was provided concurrently in Arabic and English languages. The study participants were conveniently recruited through the authors’ network in Arab countries (a majority of which were either instructors or students in Arab universities). To reach the potential participants, the survey link was disseminated via social media and instant messaging services (Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, WhatsApp, and Messenger) directed to university students in Arab countries. The survey link was accessible from 24 April 2023, until 15 August 2023, and participation was entirely voluntary, without any incentives for participation.

The inclusion criteria, as explicitly outlined at the beginning of the questionnaire prior to seeking informed consent, clearly stated that participants must meet the following conditions: (1) an age of 18 years or older, (2) to be currently enrolled in a university in one of Arab countries (Appendix S1).

2.2. Questionnaire Structure

Following the introduction highlighting the aim of the study, a mandatory informed consent item was introduced “Do you agree to participate in this study?” with “yes” as answer being required to move into the next section of the survey, while the answer of “no” resulting in closure of the survey.

The next section assessed the socio-demographic features of the participants. The following variables were assessed: (1) age as a scale variable; (2) sex (male vs. female); (3) current country of residence (Algeria, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Yemen); (4) ethnicity (Arab vs. non-Arab); (5) School/College/Faculty (health vs. scientific vs. humanities); (6) University (public vs. private); (7) current educational level (bachelor (BSc) vs. masters (MSc) vs. doctorate (PhD)); (8) The latest grade point average (GPA) (excellent, very good, good, satisfactory, and unsatisfactory).

This was followed by two questions: have you heard of ChatGPT before the study? (Yes vs. No) with an answer of “No” resulting in submission of the response and closure of the survey. An answer of “Yes” resulted in movement to the next question “Have you used ChatGPT before the study?” (Yes vs. No). An answer of “No” resulted in moving into the attitude scale questions (13 items), while the answer of “yes” resulted in moving into the attitude and usage scale questions altogether (25 items). The items comprising the constructs of TAME-ChatGPT is shown in (Appendix S1).

Each scale item was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale, where “agree” corresponded to a score of 5, “somewhat agree” to 4, “neutral/no opinion” to 3, “somewhat disagree” to 2, and “disagree” to 1. Conversely, the scoring was reversed for the items indicating a negative attitude (Appendix S1).

2.3. Ethics Statement

The current study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Faculty of Pharmacy – Applied Science Private University (approval number: 2023-PHA-21).

In the introductory section of the survey, the following issues were clearly stated: (1) assurance of the confidentiality and anonymity of the responses; (2) confirmation of the participant status as current university students in an Arab country; (3) confirmation of voluntary participation in the survey. This was followed by the mandatory informed consent question “Do you agree to participate in this study?” which was necessary for completion of the survey.

2.4. Statistical and Data Analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. AMOS was used to conduct the CFA and to analyze the fitness of models.

Measures of central tendency (mean, median) and dispersion (SD, IQR) were used for descriptive statistics. Seven constructs were evaluated as scale variables for those who heard of ChatGPT as follows (the first four constructs were assessed only among those who used ChatGPT):

(1) Perceived usefulness comprising six items with a maximum score of 30 indicating agreement that ChatGPT is useful, a score of 18 indicating neutral attitude to the usefulness of ChatGPT and a score of 6 indicating disagreement that ChatGPT is useful;

(2) Behavioral/cognitive factors comprising three items with a maximum score of 15 indicating higher role of these factors as determinants of ChatGPT use, a score of 9 indicating that these factors neither strongly influence nor discourage the use of ChatGPT and a score of 3 indicating minimal impact of these factors as determinants of ChatGPT use;

(3) Perceived risk of use comprising three items, which were reverse coded with a maximum score of 15 indicating high perceived risks in relation to ChatGPT use, a score of 9 indicating neutral attitude towards the perceived risks of ChatGPT use and a score of 3 indicating low perceived risks in relation to ChatGPT use;

(4) Perceived ease of use comprising two items, with a maximum score of 10 indicating agreement that ChatGPT is easy to use, a score of 6 indicating a neutral attitude towards the ease of ChatGPT use of ChatGPT and a score of 2 indicating disagreement that ChatGPT is easy to use;

(5) General perceived risks, comprising five items which were reverse coded with a maximum score of 25 indicating high perceived risks in relation to ChatGPT in general, a score of 15 indicating neutral attitude towards the perceived risks of ChatGPT and a score of 5 indicating low perceived risks in relation to ChatGPT in general;

(6) Anxiety comprising three items, which were reverse coded with a maximum score of 15 indicating high anxiety in relation to ChatGPT as a technological tool, a score of 9 indicating neutral attitude and a score of 3 indicating low anxiety in relation to ChatGPT; and

(7) Attitude to technology and social influence comprising five items with a maximum score of 25 indicating positive attitude towards technology and higher role of the social influence, a score of 15 indicating neutral attitude a score of 5 indicating negative attitude towards technology and lower role of the social influence.

The CFA was employed to assess the structural validity of the TAME-ChatGPT constructs. Specifically, CFA for the usage sub-scales was conducted among ChatGPT users (n = 551), while CFA for the attitude sub-scales was conducted among those who heard of ChatGPT (n = 1048). The following model fit indices were employed: χ2/degree of freedom (df), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI). Standardized factor loadings for each scale item were also determined.

Multivariable regression analysis was performed to investigate the possible factors influencing ChatGPT usage scores. The variables considered in this analysis included participants’ country of origin, age, and GPA.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Sample

The final study sample comprised a total of 2240 participants who completed the survey representing five countries (Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, and Lebanon), with a mean age of 22.25±4.58 years and 72.1% females (n = 1615). Moreover 46.8% have heard about ChatGPT, of which 52.6% indicated using ChatGPT before participation in the study. Other characteristics of the sample can be found in (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and other characteristics of the participants (n = 2240).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and other characteristics of the participants (n = 2240).

| Characteristic |

Number (%) |

| Country |

|

| Egypt |

417 (18.6%) |

| Iraq |

736 (32.9%) |

| Jordan |

242 (10.8%) |

| Kuwait |

582 (26.0%) |

| Lebanon |

263 (11.7%) |

| Sex |

|

| Male |

625 (27.9%) |

| Female |

1615 (72.1%) |

| University |

|

| Public |

983 (43.9%) |

| Private |

1257 (56.1%) |

| Self-reported latest GPA |

|

| Excellent |

537 (24.0%) |

| Very good |

765 (34.2%) |

| Good |

759 (33.9%) |

| Satisfactory |

138 (6.2%) |

| Unsatisfactory |

31 (1.4%) |

| Have heard of ChatGPT (yes) |

1048 (46.8%) |

| Have used ChatGPT (yes) |

551 (52.6%) * |

| |

Mean ± SD |

| Age (years) |

22.25 ± 4.58 |

| Perceived usefulness * |

23.30 ± 4.65 |

| Behavior * |

9.77 ± 3.03 |

| Perceived risk of use * |

7.56 ± 2.87 |

| Perceived ease of use * |

8.98 ± 1.30 |

| Anxiety |

6.97 ± 3.04 |

| Technology social influence |

19.72 ± 3.74 |

| Perceived risk |

12.43 ± 4.41 |

3.2. General Description of the TAME-ChatGPT Scores in the Study Sample

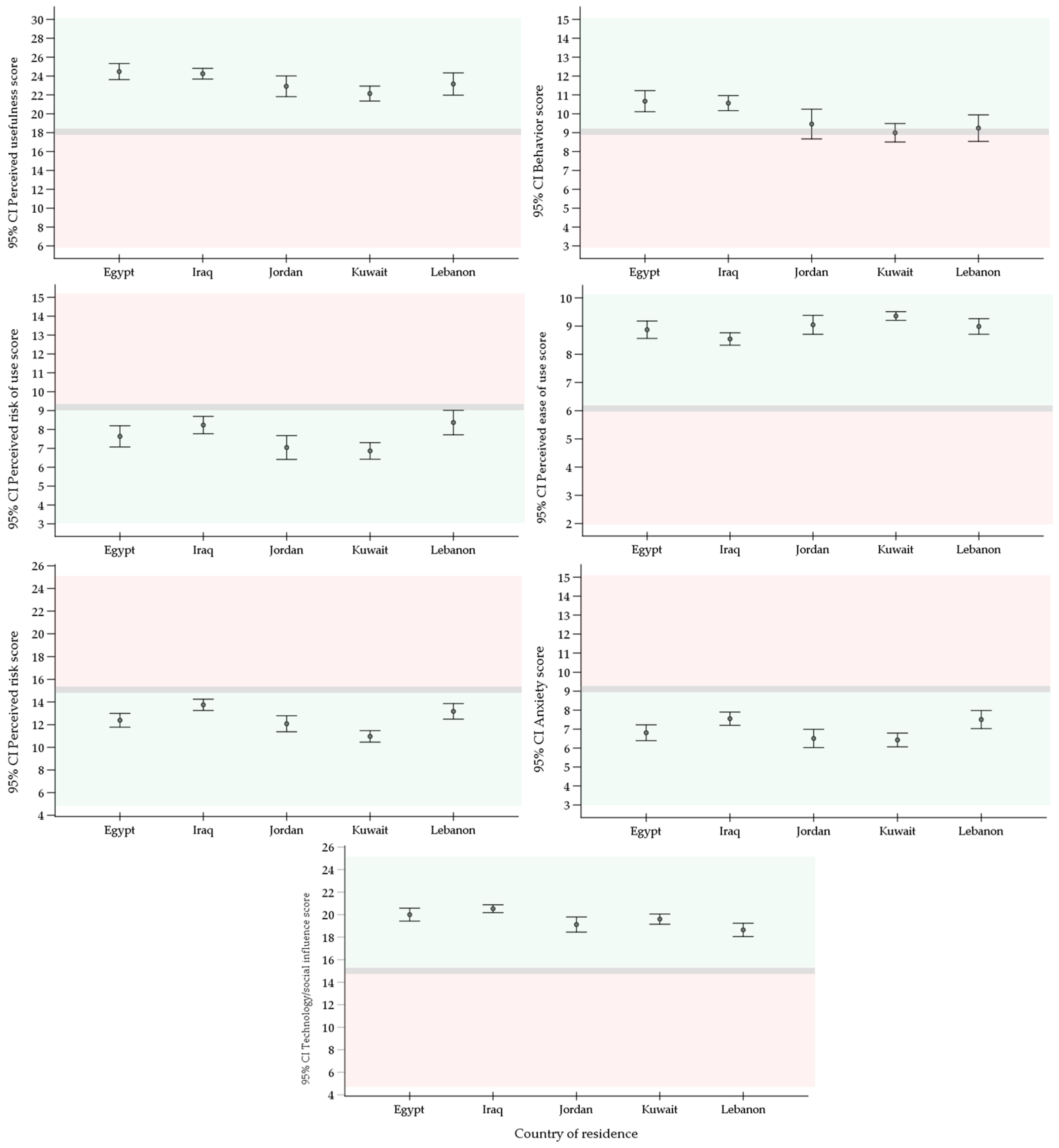

Descriptive analyses of the key TAME-ChatGPT constructs’ scores revealed a generally positive attitude towards ChatGPT and its use in the study sample, as reflected in (Table 2 and Figure 1).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the TAME-ChatGPT constructs in the study sample.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the TAME-ChatGPT constructs in the study sample.

| Construct |

Perceived usefulness |

Behavior score |

Perceived risk of use |

Perceived ease of use |

General perceived risk |

Anxiety |

Technology/social influence |

| Number |

551 |

551 |

551 |

551 |

1048 |

1048 |

1048 |

| Mean±SD |

23.3±4.6 |

9.8±3.0 |

7.6±2.9 |

9.0±1.3 |

12.4±4.4 |

7.0±3.0 |

19.7±3.7 |

| Median |

24 |

10 |

7 |

10 |

12 |

6 |

20 |

| Minimum |

6 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

5 |

3 |

5 |

| Maximum |

30 |

15 |

15 |

10 |

25 |

15 |

25 |

| IQR |

21–27 |

8–12 |

5–9 |

8–10 |

9–15 |

5–9 |

18–23 |

| Attitude |

Agreement |

Positive influence |

Low perceived risk |

Agreement |

Low perceived risk |

Low anxiety |

Positive influence |

Figure 1.

Descriptive analyses of the key TAME-ChatGPT constructs’ scores stratified by country of residence for the participants. CI: confidence interval of the mean. Positive attitude is highlighted in light green, negative attitude in light red, and neutral attitude in grey.

Figure 1.

Descriptive analyses of the key TAME-ChatGPT constructs’ scores stratified by country of residence for the participants. CI: confidence interval of the mean. Positive attitude is highlighted in light green, negative attitude in light red, and neutral attitude in grey.

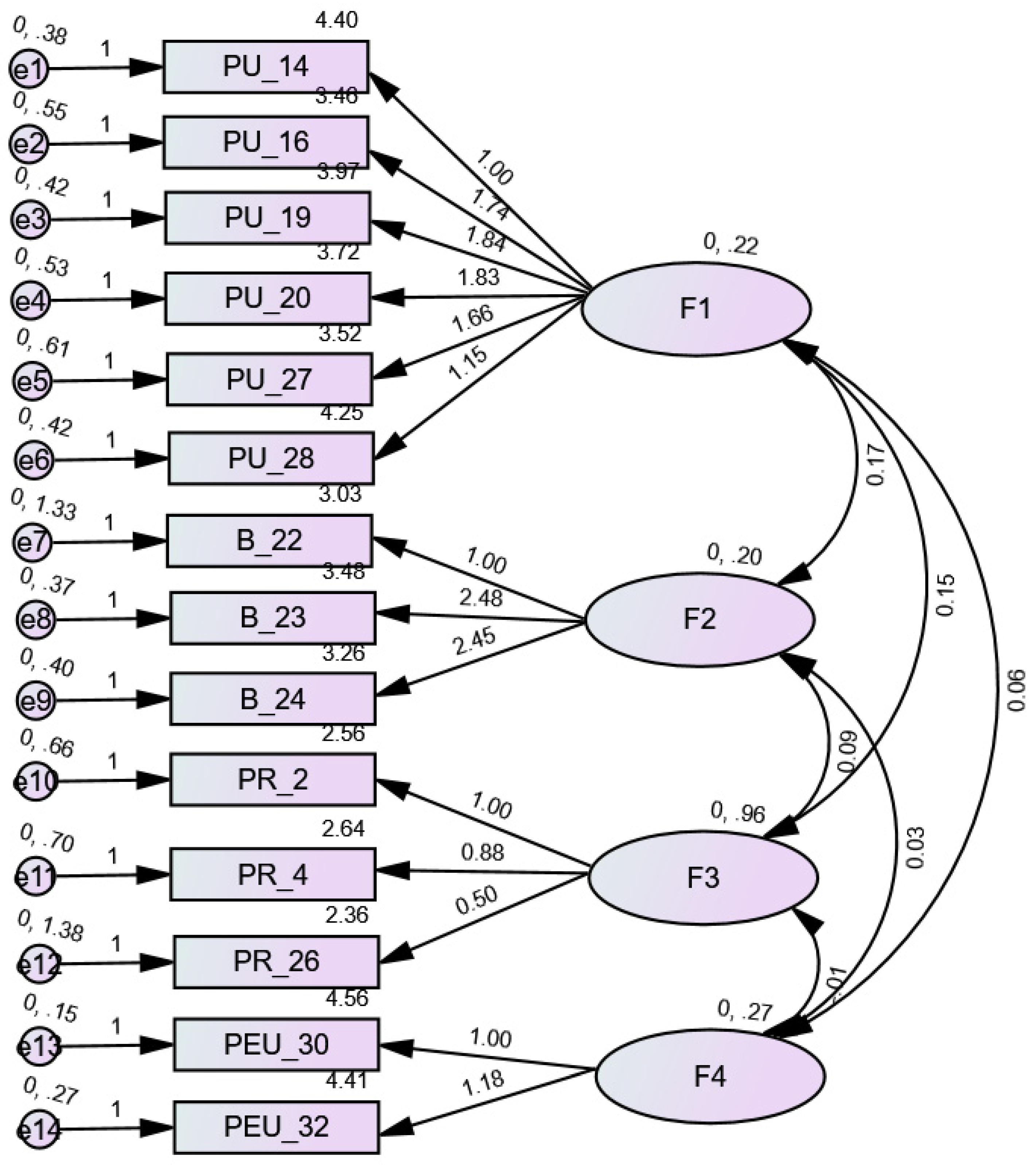

3.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The CFA results of the TAME-ChatGPT usage scale was conducted on those who have used ChatGPT (n = 551). The fit indices were adequate as follows: χ2/df = 300.20/71 = 4.23, p < .001, RMSEA = .077 (90% CI: .068 – .086), SRMR = .050, CFI = .923, and TLI = .901. The standardized estimates of factor loadings are shown in (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Items of the ChatGPT usage scale and standardized estimates of factor loadings from the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in participants who have used ChatGPT. F1: Perceived usefulness (PU), F2: Behavioral/cognitive factors (B), F3: Perceived risk of use (PR), F4: Perceived ease of use (PEU).

Figure 2.

Items of the ChatGPT usage scale and standardized estimates of factor loadings from the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in participants who have used ChatGPT. F1: Perceived usefulness (PU), F2: Behavioral/cognitive factors (B), F3: Perceived risk of use (PR), F4: Perceived ease of use (PEU).

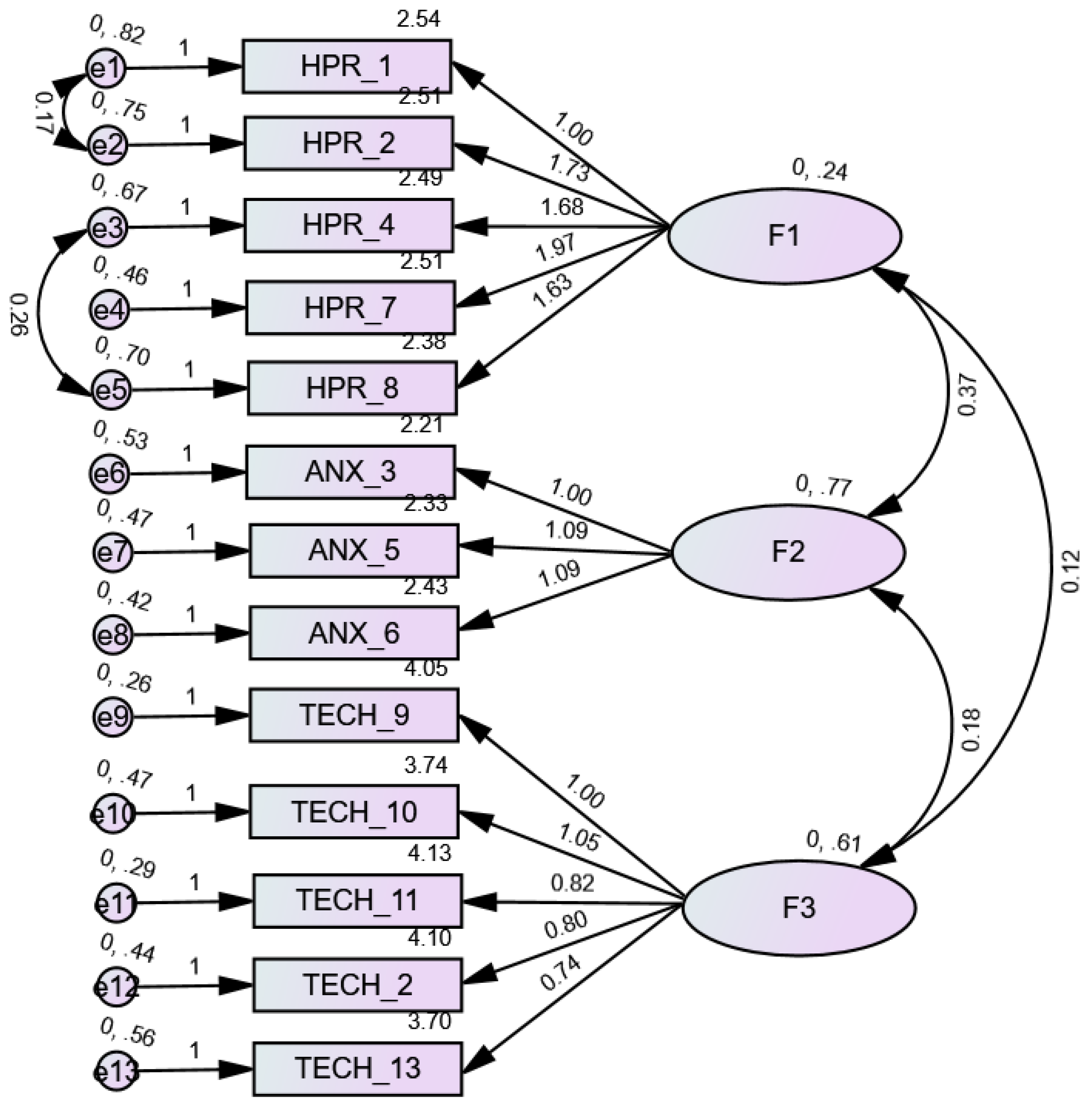

The CFA results of the attitude scale was conducted on those who have used ChatGPT (n = 1048). The fit indices were adequate as follows: χ2/df = 436.67/62 = 7.04, p < .001, RMSEA = .076 (90% CI: .069 – .083), SRMR = .038, CFI = .942, and TLI = .927. When adding correlations between the items 1-2 and 4-8, the fit indices improved as follows: χ2/df = 288.28/60 = 4.81, p < .001, RMSEA = .060 (90% CI: .053 – .067), SRMR = .032, CFI = .965, and TLI = .954. The standardized estimates of factor loadings are shown in (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Items of the ChatGPT attitude scale and standardized estimates of factor loadings from the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in participants who have heard about ChatGPT. F1: Perceived risk in general (HPR), F2: Anxiety (ANX), F3: Attitude to technology/social influence (TECH).

Figure 3.

Items of the ChatGPT attitude scale and standardized estimates of factor loadings from the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in participants who have heard about ChatGPT. F1: Perceived risk in general (HPR), F2: Anxiety (ANX), F3: Attitude to technology/social influence (TECH).

3.4. Bivariate analysis of factors associated with ChatGPT usage

The results of the bivariate analysis are summarized in (

Table 3), which showed a statistically significant differences in ChatGPT usage scale based on country of residence, type of university, and self-reported GPA.

A higher mean ChatGPT usage total score was found in Egypt compared to the other countries, in students from private universities and in those who have satisfactory GPA. Moreover, older age was significantly associated with lower ChatGPT usage scores (r = −.18; p < .001).

3.5. Multivariable analysis

Being from Iraq (Beta = −2.91), Jordan (Beta = −4.77), Kuwait (Beta = −5.00) and Lebanon (Beta = −4.58) compared to Egypt and older age (Beta = −.11) were significantly associated with lower ChatGPT usage total scores. Moreover, having a very good (Beta = 1.73) and good (Beta = 2.47) GPA compared to excellent was significantly associated with higher ChatGPT usage total scores (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

In this study, a slightly less than a quarter of the participating students indicated the use of ChatGPT highlighting the widespread adoption of this LLM-based tool, previously recognized as the most rapidly expanding consumer application in history [

56,

57,

58]. This versatility of ChatGPT use or the intention to use it as an aid in university assignments was illustrated recently in a large multinational study by Ibrahim et al. [

59]. This recent multinational study that was conducted among academics and students in Brazil, India, Japan, UK, and USA, regarding their perspectives on ChatGPT, indicated that a majority of students intend to use ChatGPT for assignment support and anticipate that their peers would endorse its usage, implying a potential shift towards ChatGPT use becoming a standard practice among university students [

59].

Several previous studies indicated the potential utility of ChatGPT as a prime example among other LLMs in higher education [

1,

18,

26,

60,

61,

62]. Based on the prospects of ChatGPT in higher education, a previous study explored the validity of a survey instrument to assess the factors influencing the adoption of this novel tool among university students in health schools in Jordan [

48]. The current study confirmed the validity of this survey instrument termed “TAME-ChatGPT” as a valuable tool to elucidate the determinants of ChatGPT use and attitude towards this novel AI-based conversational model.

In this study, the major findings illustrated that the adoption of ChatGPT among university students is influenced by both socio-demographic variables and various TAM constructs as modeled in “TAME-ChatGPT”. Additionally, the study findings revealed that ChatGPT was perceived to have both positive and negative aspects among the participating students reflecting the ongoing debate regarding ChatGPT [

1,

14]. This appears conceivable in light of the current evidence showing that the use of AI-based tools for educational purposes were perceived as a double-edged sword [

1,

5,

14,

63]. On one hand, these tools can be valuable in delivering timely, efficient, and personalized support to a broad student population promoting equity in education [

64,

65,

66,

67]. On the other hand, valid concerns should be emphasized including the possible generation of inaccurate and biased educational content among other ethical concerns [

1,

5,

68,

69].

Therefore, to successfully exploit the potential of ChatGPT in the learning and teaching processes, the current study revealed the following relevant factors: First, one of the most promising features of ChatGPT is its ease of use, which was reflected by general agreement of a majority of the participants students in this study. The ease of ChatGPT use is a notable feature of this tool promoting its widespread accessibility and usability [

57]. As previously illustrated in various studies, ChatGPT responds to queries in various languages, with notable capabilities facilitating the generation of coherent responses [

11,

33,

70,

71,

72]. A recent study among university students in Jordan by Ajlouni et al. showed that a majority of participants (73%) agreed on the potential of ChatGPT in facilitating the learning process [

73]. As a “smart” user-friendly tool, ChatGPT has been shown to be suitable for a wide range of applications, including answering questions, text generation, and aiding in writing of various tasks [

33,

74,

75]. Thus, it is conceivable that this particular construct showed a high score among the study sample in various settings.

Based on the findings of the current study, the incorporation of ChatGPT in the learning process among university students can benefit from the ease-of-use feature which was identified as a major factor driving ChatGPT use in the study sample. This finding is in line with results of previous studies which showed that effort expectancy was an important determinant of adoption of novel educational technologies including ChatGPT [

61,

76,

77].

The user-friendly nature of ChatGPT facilitate its immediate accessibility to students of varying backgrounds [

33]. Through providing an immediate source for clarifying complex concepts, ChatGPT can reduce barriers to learning in higher education [

25]. The ease-of-use can also offer a personalized learning experience that addresses individual student needs and preferences. Taking into consideration the current study setting in Arab-speaking countries, and based on English language prominence in higher education, ChatGPT can be a valuable tool assisting non-native English speakers to improve the learning process, thereby promoting inclusivity and equity in higher education [

69,

78,

79]. Furthermore, the prompt ability of ChatGPT in information retrieval and content generation can allow university students to allocate more time to understand complex educational materials leading to more effective achievement of the intended learning outcomes [

1,

25,

80].

Second, another major determinant of ChatGPT use among the participating students in this study was the perceived usefulness of this novel tool via providing accuracy and speed. Numerous previous studies highlighted that the perceived usefulness of a novel technology is a key factor influencing the intention of users to adopt such a technology [

47,

81,

82,

83,

84].

The study findings highlighted the versatile advantages of ChatGPT in supporting academic tasks among university students. This was reflected by generally high agreement of the participants on the “perceived usefulness” construct items, highlighting that ChatGPT could enhance efficiency in university assignments and duties, aligning with students’ beliefs regarding usefulness of ChatGPT for educational purposes [

14,

59].

Third, in this study, the positive attitude towards technology as well as the social influence were found as major factors driving the adoption of ChatGPT among the university students. A majority of the sample scored high on the “attitude towards technology/social influence” construct. The responses from participants in this study emphasized the key role of readiness to accept novel technological tools in achieving academic success. This result is conceivable considering that the inclination to embrace novel technological tools, as well as the influence of peers, collectively emerge as key determinants contributing to a successful adoption of new technologies within an educational context [

85,

86,

87,

88].

Fourth, among the other factors identified as important determinants for ChatGPT adoption among university students in this study were the behavioral/cognitive factors. Certain behavioral and cognitive factors, such as habits, beliefs, and thought processes, are expected to play a significant role in shaping the attitude towards a novel technology such as ChatGPT [

89,

90,

91]. Therefore, it is expected that participants who reported prior experience with tools similar to ChatGPT could be more comfortable and familiar with such a novel technology, rendering those students more likely to adopt ChatGPT for educational purposes. Moreover, the spontaneous use of ChatGPT to retrieve information for academic assignments suggests an intrinsic inclination to rely on the tool, indicating a cognitive readiness to integrate it among university students as indicated by the recent multinational study by Ibrahim et al., which showed that the majority of students (>90%) intended to use ChatGPT as an aiding tool in their assignments in the coming semester [

59].

Fifth, the generally low perceived risks and low anxiety levels among the participating university students in this study suggest a readiness to adopt ChatGPT, in spite of the recognized concerns and known risks associated with this novel AI-based technology [

92,

93,

94]. These concerns that were shown previously included possible unreliability of the generated content, risk of plagiarism, security concerns, risk of violating the academic policies, and privacy issues when using ChatGPT [

5,

14,

18]. The finding of low perceived risks in the study sample suggest that the aforementioned concerns were not strongly perceived among students in the sample and indicate the readiness to embrace ChatGPT in the learning process despite the appreciated concerns.

Furthermore, the generally low “anxiety” scores, including the fear of declining the critical thinking skills, over-dependence on technology, and diminished originality in assignments, suggest that the participating students were not anxious about these potential drawbacks. Instead, the study findings suggest that university students could view ChatGPT as a valuable tool in education with low perceived anxiety regarding possible breaches of academic integrity or issues in the development of their skills.

Finally, if ChatGPT among other relevant LLM are to be implemented as a tool for educational purposes, the study findings suggest that the university policies should be tailored in various settings and based on factors such as age and academic performance as reflected by GPA. Different age groups of university students may have varying needs, preferences, and different levels of familiarity with technological advancements. Tailoring policies to accommodate these generational disparities can enhance the overall student experience and acceptance of ChatGPT. Additionally, students with diverse academic achievements may have distinct requirements for utilizing ChatGPT effectively. Customizing policies that address these variations can promote equitable academic achievements and ensure that the tool aligns with students’ academic goals [

14].

Limitations of the study requires careful considerations upon attempting to interpret the findings. These limitations included the approach of sampling which was convenience-based. Such an approach is limited by possible selection bias with subsequent lack of generalizability; however, the selection of this sampling approach was based on cost issues, efficiency, and being simple to implement [

95]. Other limitations included the cross-sectional design, limiting the ability to establish causality or to explore the temporal changes in attitudes and usage patterns of ChatGPT. Additionally, the possible response bias should be considered in light of the possibility of perceived social desirability, in light of the controversy surrounding ChatGPT use in academia.

5. Conclusions

The successful adoption of ChatGPT among university students is expected to be related to multifaceted factors as intricately inferred through the validated “TAME-ChatGPT” instrument. These factors include the highly perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, positive attitude towards technology in general together with the effect of social influence, and the low anxiety and the low perceived risks. Understanding the dynamic interplay of these factors is important for higher education institutions, educators, policymakers, and other stakeholders if they attempt the integration of AI technologies into educational practices. These TAM-based factors together with demographic factors could collectively influence the students’ attitudes towards ChatGPT, rendering them more likely to view it positively and use it beneficially to achieve the intended learning outcomes in academic settings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Appendix S1: Consent form and TAME-ChatGPT scale.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.; methodology, Maram Abdaljaleel, M.B., Mariam Alsanafi, N.A.S., H.A., D.M., A.H.M., B.A.R.H., A.M.W., S.S.F., S.E.K., M.R., A.S., D.H.A., N.O.M., R.A.-Z., R.K., F.F.-R., R.H., S.H., and M.S.; software, S.H. and M.S.; validation, Maram Abdaljaleel, M.B., S.H., and M.S.; formal analysis, Maram Abdaljaleel, M.B., S.H., and M.S.; investigation, Maram Abdaljaleel, M.B., Mariam Alsanafi, N.A.S., H.A., D.M., A.H.M., B.A.R.H., A.M.W., S.S.F., S.E.K., M.R., A.S., D.H.A., N.O.M., R.A.-Z., R.K., F.F.-R., R.H., S.H., and M.S.; resources, Maram Abdaljaleel, M.B., S.H., and M.S.; data curation, Maram Abdaljaleel, M.B., Mariam Alsanafi, N.A.S., H.A., D.M., A.H.M., B.A.R.H., A.M.W., S.S.F., S.E.K., M.R., A.S., D.H.A., N.O.M., R.A.-Z., R.K., F.F.-R., R.H., S.H., and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Maram Abdaljaleel, S.H., and M.S.; writing—review and editing, Maram Abdaljaleel, M.B., Mariam Alsanafi, N.A.S., H.A., D.M., A.H.M., B.A.R.H., A.M.W., S.S.F., S.E.K., M.R., A.S., D.H.A., N.O.M., R.A.-Z., R.K., F.F.-R., R.H., S.H., and M.S.; visualization, S.H. and M.S.; supervision, Maram Abdaljaleel, M.B., S.H., and M.S.; project administration, Maram Abdaljaleel, M.B., S.H., and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Faculty of Pharmacy – Applied Science Private University (approval number: 2023-PHA-21, date of approval: May 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study through a mandatory item in the survey necessary for successful completion and submission of the response.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author (M.S.).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| AI |

Artificial intelligence |

| CFA |

Confirmatory factor analysis |

| CFI |

Comparative fit index |

| df |

Degree of freedom |

| GPA |

Grade point average |

| LLM |

Large language model |

| RMSEA |

Root mean square error of approximation |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| SRMR |

Standardized root mean square residual |

| TAM |

Technology acceptance model |

| TAME-ChatGPT |

Technology Acceptance Model Edited to Assess ChatGPT Adoption |

| TLI |

Tucker-Lewis index |

| UAE |

The United Arab Emirates |

References

- Sallam, M. ChatGPT Utility in Healthcare Education, Research, and Practice: Systematic Review on the Promising Perspectives and Valid Concerns. Healthcare (Basel) 2023, 11, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, H.; Burke, D. Artificial intelligence in higher education: the state of the field. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2023, 20, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, P.; Lin, Z. Artificial Intelligence in Education: A Review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 75264–75278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, B.; Wooden, O. Managing the Strategic Transformation of Higher Education through Artificial Intelligence. Administrative Sciences 2023, 13, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassini, S. Shaping the Future of Education: Exploring the Potential and Consequences of AI and ChatGPT in Educational Settings. Education Sciences 2023, 13, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslit, E.R. Voyaging Beyond Chalkboards: Unleashing Tomorrow's Minds through AI-Driven Frontiers in Literature and Language Education. Preprints 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleiss, J.; Laupichler, M.C.; Raupach, T.; Stober, S. AI Course Design Planning Framework: Developing Domain-Specific AI Education Courses. Education Sciences 2023, 13, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, G.; Yankova, T.; Klisarova-Belcheva, S.; Dimitrov, A.; Bratkov, M.; Angelov, D. Effects of Generative Chatbots in Higher Education. Information 2023, 14, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurzo, A.; Strunga, M.; Urban, R.; Surovková, J.; Afrashtehfar, K.I. Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Dental Education: A Review and Guide for Curriculum Update. Education Sciences 2023, 13, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. ChatGPT: get instant answers, find creative inspiration, and learn something new. Available online: https://openai.com/chatgpt (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Sallam, M.; Salim, N.A.; Al-Tammemi, A.B.; Barakat, M.; Fayyad, D.; Hallit, S.; Harapan, H.; Hallit, R.; Mahafzah, A. ChatGPT Output Regarding Compulsory Vaccination and COVID-19 Vaccine Conspiracy: A Descriptive Study at the Outset of a Paradigm Shift in Online Search for Information. Cureus 2023, 15, e35029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giansanti, D. Precision Medicine 2.0: How Digital Health and AI Are Changing the Game. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2023, 13, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, C.K. What Is the Impact of ChatGPT on Education? A Rapid Review of the Literature. Education Sciences 2023, 13, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawas, S. ChatGPT: Empowering lifelong learning in the digital age of higher education. Education and Information Technologies 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giansanti, D. The Chatbots Are Invading Us: A Map Point on the Evolution, Applications, Opportunities, and Emerging Problems in the Health Domain. Life 2023, 13, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.; Tang, J.; Roll, I.; Fels, S.; Yoon, D. The impact of artificial intelligence on learner–instructor interaction in online learning. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2021, 18, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Joint Research Centre; Tuomi, I.; Punie, Y.; Vuorikari, R.; Cabrera, M. The impact of Artificial Intelligence on learning, teaching, and education; Publications Office: 2018.

- Sallam, M.; Salim, N.A.; Barakat, M.; Al-Tammemi, A.B. ChatGPT applications in medical, dental, pharmacy, and public health education: A descriptive study highlighting the advantages and limitations. Narra J 2023, 3, e103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borji, A. A Categorical Archive of ChatGPT Failures. Research Square (preprint) 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aver, B.; Fošner, A.; Alfirević, N. Higher Education Challenges: Developing Skills to Address Contemporary Economic and Sustainability Issues. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akour, M.; Alenezi, M. Higher Education Future in the Era of Digital Transformation. Education Sciences 2022, 12, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilbault, M. Students as customers in higher education: The (controversial) debate needs to end. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2018, 40, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kumaim, N.H.; Hassan, S.H.; Shabbir, M.S.; Almazroi, A.A.; Abu Al-Rejal, H.M. Exploring the Inescapable Suffering Among Postgraduate Researchers: Information Overload Perceptions and Implications for Future Research. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education (IJICTE) 2021, 17, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breier, M. From ‘financial considerations’ to ‘poverty’: towards a reconceptualisation of the role of finances in higher education student drop out. Higher Education 2010, 60, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Khan, S.; Khan, I.H. Unlocking the opportunities through ChatGPT Tool towards ameliorating the education system. BenchCouncil Transactions on Benchmarks, Standards and Evaluations 2023, 3, 100115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro-Rueda, M.; Fernández-Cerero, J.; Fernández-Batanero, J.M.; López-Meneses, E. Impact of the Implementation of ChatGPT in Education: A Systematic Review. Computers 2023, 12, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, D.T.K.; Leung, J.K.L.; Chu, S.K.W.; Qiao, M.S. Conceptualizing AI literacy: An exploratory review. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 2021, 2, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornberger, M.; Bewersdorff, A.; Nerdel, C. What do university students know about Artificial Intelligence? Development and validation of an AI literacy test. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 2023, 5, 100165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wogu, I.A.P.; Misra, S.; Olu-Owolabi, E.F.; Assibong, P.A.; Udoh, O.D.; Ogiri, S.; Damasevicius, R. Artificial intelligence, artificial teachers and the fate of learners in the 21st century education sector: Implications for theory and practice. International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics 2018, 119, 2245–2259, doi:NA, available from: https://acadpubl.eu/hub/2018-119-16/issue16b.html.. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra-Carrillo, B.; Katovich, K.; Bunge, S.A. Does higher education hone cognitive functioning and learning efficacy? Findings from a large and diverse sample. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0182276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunday, O.J.; Adesope, O.O.; Maarhuis, P.L. The effects of smartphone addiction on learning: A meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior Reports 2021, 4, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulesza, J.; Ii, G.; Nezlek, G. More Technology, Less Learning? Information Systems Education Journal (ISEDJ) 2011, 9, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, P.P. ChatGPT: A comprehensive review on background, applications, key challenges, bias, ethics, limitations and future scope. Internet of Things and Cyber-Physical Systems 2023, 3, 121–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Meng, Y.; Ratner, A.; Krishna, R.; Shen, J.; Zhang, C. Large Language Model as Attributed Training Data Generator: A Tale of Diversity and Bias. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.15895 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazer, L.H.; Zatarah, R.; Waldrip, S.; Ke, J.X.C.; Moukheiber, M.; Khanna, A.K.; Hicklen, R.S.; Moukheiber, L.; Moukheiber, D.; Ma, H.; et al. Bias in artificial intelligence algorithms and recommendations for mitigation. PLOS Digital Health 2023, 2, e0000278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zajko, M. Artificial intelligence, algorithms, and social inequality: Sociological contributions to contemporary debates. Sociology Compass 2022, 16, e12962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, A. Why addressing digital inequality should be a priority. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries 2023, 89, e12255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Lawton, W. Universities, the digital divide and global inequality. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 2018, 40, 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, D.T.K.; Leung, J.K.L.; Su, J.; Ng, R.C.W.; Chu, S.K.W. Teachers' AI digital competencies and twenty-first century skills in the post-pandemic world. Educ Technol Res Dev 2023, 71, 137–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofosu-Ampong, K.; Acheampong, B.; Kevor, M.-O.; Amankwah-Sarfo, F. Acceptance of Artificial Intelligence (ChatGPT) in Education: Trust, Innovativeness and Psychological Need of Students. Journal of Information & Knowledge Management 2023, 13, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, A.; Solaiman, M.; Alhasan, K.; Temsah, M.H.; Sayed, G. Integrating ChatGPT in Medical Education: Adapting Curricula to Cultivate Competent Physicians for the AI Era. Cureus 2023, 15, e43036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooli, C. Chatbots in Education and Research: A Critical Examination of Ethical Implications and Solutions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazi, T.; Islam, M.; Sezan, S.; Sanad, Z.; Ataur, A.-J. Impact of ChatGPT on Academic Performance among Bangladeshi Undergraduate Students. International Journal of Research In Science & Engineering 2023, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chen, Y.-L.; Por, L.Y.; Ku, C.S. A Systematic Literature Review of Information Security in Chatbots. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 6355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, A. The impact of ChatGPT on blended learning: Current trends and future research directions. International Journal of Data and Network Science 2023, 7, 2029–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyoussef, I.Y. Factors Influencing Students’ Acceptance of M-Learning in Higher Education: An Application and Extension of the UTAUT Model. Electronics 2021, 10, 3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, H.; Rada, R. Understanding the Influence of Perceived Usability and Technology Self-Efficacy on Teachers’ Technology Acceptance. Journal of Research on Technology in Education 2011, 43, 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Salim, N.A.; Barakat, M.; Al-Mahzoum, K.; Al-Tammemi, A.B.; Malaeb, D.; Hallit, R.; Hallit, S. Assessing Health Students' Attitudes and Usage of ChatGPT in Jordan: Validation Study. JMIR Med Educ 2023, 9, e48254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalov, F.; Santandreu Calonge, D.; Gurrib, I. New Era of Artificial Intelligence in Education: Towards a Sustainable Multifaceted Revolution. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, C.K.; Bhat, M.A.; Khan, S.T.; Subramaniam, R.; Khan, M.A.I. What drives students toward ChatGPT? An investigation of the factors influencing adoption and usage of ChatGPT. Interactive Technology and Smart Education 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Cordero, E.; Rodriguez-Rad, C.; Ledesma-Chaves, P.; Sánchez del Río-Vázquez, M.-E. Analysis of factors affecting the effectiveness of face-to-face marketing learning via TikTok, YouTube and video conferencing. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun Baek, T.; Kim, M. Is ChatGPT scary good? How user motivations affect creepiness and trust in generative artificial intelligence. Telematics and Informatics 2023, 83, 102030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangunić, N.; Granić, A. Technology acceptance model: a literature review from 1986 to 2013. Universal Access in the Information Society 2015, 14, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazos, T.A. Applied Psychometrics: Sample Size and Sample Power Considerations in Factor Analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in General. Psychology 2018, 9, 2207–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundfrom, D.J.; Shaw, D.G.; Ke, T.L. Minimum Sample Size Recommendations for Conducting Factor Analyses. International Journal of Testing 2005, 5, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartz, D.; As ChatGPT's popularity explodes, U.S. lawmakers take an interest. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/technology/chatgpts-popularity-explodes-us-lawmakers-take-an-interest-2023-02-13/ (accessed on 19 September 2023).

- Jianning, L.; Amin, D.; Jens, K.; Jan, E. ChatGPT in Healthcare: A Taxonomy and Systematic Review. medRxiv 2023, preprint, 2023.2003.2030.23287899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, R. Practical Applications of ChatGPT in Undergraduate Medical Education. J Med Educ Curric Dev 2023, 10, 23821205231178449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.; Liu, F.; Asim, R.; Battu, B.; Benabderrahmane, S.; Alhafni, B.; Adnan, W.; Alhanai, T.; AlShebli, B.; Baghdadi, R.; et al. Perception, performance, and detectability of conversational artificial intelligence across 32 university courses. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 12187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, J.G.; Urbanowicz, R.J.; Martin, P.C.N.; O'Connor, K.; Li, R.; Peng, P.C.; Bright, T.J.; Tatonetti, N.; Won, K.J.; Gonzalez-Hernandez, G.; et al. ChatGPT and large language models in academia: opportunities and challenges. BioData Min 2023, 16, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.M.R.; Montoya, M.S.R.; Fernández, M.B.; Lara, F.L. Use of ChatGPT at university as a tool for complex thinking: Students' perceived usefulness. NAER: Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research 2023, 12, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Kamel Boulos, M.N. Generative AI in Medicine and Healthcare: Promises, Opportunities and Challenges. Future Internet 2023, 15, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaraman, M.; K, S.P.; Jeyaraman, N.; Nallakumarasamy, A.; Yadav, S.; Bondili, S.K. ChatGPT in Medical Education and Research: A Boon or a Bane? Cureus 2023, 15, e44316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, J.; Kasapovic, A.; Jansen, T.; Kaczmarczyk, R. Artificial Intelligence in Medical Education: Comparative Analysis of ChatGPT, Bing, and Medical Students in Germany. JMIR Med Educ 2023, 9, e46482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. Using ChatGPT as a Learning Tool in Acupuncture Education: Comparative Study. JMIR Med Educ 2023, 9, e47427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Totlis, T.; Natsis, K.; Filos, D.; Ediaroglou, V.; Mantzou, N.; Duparc, F.; Piagkou, M. The potential role of ChatGPT and artificial intelligence in anatomy education: a conversation with ChatGPT. Surg Radiol Anat 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karabacak, M.; Ozkara, B.B.; Margetis, K.; Wintermark, M.; Bisdas, S. The Advent of Generative Language Models in Medical Education. JMIR Med Educ 2023, 9, e48163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safranek, C.W.; Sidamon-Eristoff, A.E.; Gilson, A.; Chartash, D. The Role of Large Language Models in Medical Education: Applications and Implications. JMIR Med Educ 2023, 9, e50945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, H.; Tayarani-Najaran, M.-H.; Yaqoob, M. Exploring Computer Science Students’ Perception of ChatGPT in Higher Education: A Descriptive and Correlation Study. Education Sciences 2023, 13, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kshetri, N.; Hughes, L.; Slade, E.L.; Jeyaraj, A.; Kar, A.K.; Baabdullah, A.M.; Koohang, A.; Raghavan, V.; Ahuja, M.; et al. Opinion Paper: “So what if ChatGPT wrote it?” Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management 2023, 71, 102642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumeliotis, K.I.; Tselikas, N.D. ChatGPT and Open-AI Models: A Preliminary Review. Future Internet 2023, 15, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiba, D.; Fraboni, M.C. AI-Supported Academic Advising: Exploring ChatGPT’s Current State and Future Potential toward Student Empowerment. Education Sciences 2023, 13, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajlouni, A.; Abd-Alkareem Wahba, F.; Salem Almahaireh, A. Students’ Attitudes Towards Using ChatGPT as a Learning Tool: The Case of the University of Jordan. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies (iJIM) 2023, 17, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Singh, R.P. An era of ChatGPT as a significant futuristic support tool: A study on features, abilities, and challenges. BenchCouncil Transactions on Benchmarks, Standards and Evaluations 2022, 2, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Almusharraf, N. Analyzing the role of ChatGPT as a writing assistant at higher education level: A systematic review of the literature. Contemporary Educational Technology 2023, 15, ep464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, B.; Senali, M.G.; Iranmanesh, M.; Khanfar, A.; Ghobakhloo, M.; Annamalai, N.; Naghmeh-Abbaspour, B. Determinants of Intention to Use ChatGPT for Educational Purposes: Findings from PLS-SEM and fsQCA. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooda, A.; Gupta, P.; Jeyaraj, A.; Giannakis, M.; Dwivedi, Y.K. The effects of trust on behavioral intention and use behavior within e-government contexts. International Journal of Information Management 2022, 67, 102553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin-Hady, W.R.A.; Al-Kadi, A.; Hazaea, A.; Ali, J.K.M. Exploring the dimensions of ChatGPT in English language learning: a global perspective. Library Hi Tech 2023, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriansen, H.K.; Juul-Wiese, T.; Madsen, L.M.; Saarinen, T.; Spangler, V.; Waters, J.L. Emplacing English as lingua franca in international higher education: A spatial perspective on linguistic diversity. Population, Space and Place 2023, 29, e2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanvijay, A.K.D.; Pinjar, M.J.; Dhokane, N.; Sorte, S.R.; Kumari, A.; Mondal, H. Performance of Large Language Models (ChatGPT, Bing Search, and Google Bard) in Solving Case Vignettes in Physiology. Cureus 2023, 15, e42972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Xu, X. Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. MIS Quarterly 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubert, M.; Blut, M.; Brock, C.; Zhang, R.W.; Koch, V.; Riedl, R. The influence of acceptance and adoption drivers on smart home usage. European Journal of Marketing 2019, 53, 1073–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saprikis, V.; Avlogiaris, G.; Katarachia, A. Determinants of the Intention to Adopt Mobile Augmented Reality Apps in Shopping Malls among University Students. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 2021, 16, 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y.W.; Sorwar, G.; Rahman, M.S.; Hoque, M.R. The role of trust and habit in the adoption of mHealth by older adults in Hong Kong: a healthcare technology service acceptance (HTSA) model. BMC Geriatrics 2023, 23, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blut, M.; Wang, C. Technology readiness: a meta-analysis of conceptualizations of the construct and its impact on technology usage. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 2020, 48, 649–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Qadri, M.A.; Suman, R. Understanding the role of digital technologies in education: A review. Sustainable Operations and Computers 2022, 3, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markauskaite, L.; Marrone, R.; Poquet, O.; Knight, S.; Martinez-Maldonado, R.; Howard, S.; Tondeur, J.; De Laat, M.; Buckingham Shum, S.; Gašević, D.; et al. Rethinking the entwinement between artificial intelligence and human learning: What capabilities do learners need for a world with AI? Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 2022, 3, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, M.; Marín, V.I.; Dolch, C.; Bedenlier, S.; Zawacki-Richter, O. Digital transformation in German higher education: student and teacher perceptions and usage of digital media. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2018, 15, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woithe, J.; Filipec, O. Understanding the Adoption, Perception, and Learning Impact of ChatGPT in Higher Education: A qualitative exploratory case study analyzing students’ perspectives and experiences with the AI-based large language model. 2023, degree of Bachelor, doi:NA, available from: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1762617&dswid=9377.

- Shahsavar, Y.; Choudhury, A. User Intentions to Use ChatGPT for Self-Diagnosis and Health-Related Purposes: Cross-sectional Survey Study. JMIR Hum Factors 2023, 10, e47564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, C.; Liu, W. Understanding the adoption of mobile social payment: from the cognitive behavioural perspective. International Journal of Mobile Communications 2022, 20, 483–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Mijwil, M.; Hiran, K.K.; Doshi, R.; Dadhich, M.; Al-Mistarehi, A.-H.; Bala, I. ChatGPT and the Future of Academic Integrity in the Artificial Intelligence Era: A New Frontier. Al-Salam Journal for Engineering and Technology 2023, 2, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijwil, M.; Mohammad, A.; Ahmed Hussein, A. ChatGPT: Exploring the Role of Cybersecurity in the Protection of Medical Information. Mesopotamian Journal of CyberSecurity 2023, 2023, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watters, C.; Lemanski, M.K. Universal skepticism of ChatGPT: a review of early literature on chat generative pre-trained transformer. Front Big Data 2023, 6, 1224976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, J.; Putnick, D.L.; Bornstein, M.H. More than Just Convenient: The Scientific Merits of Homogeneous Convenience Samples. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 2017, 82, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).