Submitted:

21 September 2023

Posted:

26 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Assessment

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arufe-Giráldez, V.; Sanmiguel-Rodríguez, A.; Ramos-Álvarez, O.; Navarro-Patón, R. News of the Pedagogical Models in Physical Education—A Quick Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena-Morales, S.; González-Víllora, S. Physical Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Reflections and Comments for Contribution in the Educational Framework. Sport. Educ. Soc. 2023, 28, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.; Davies, M. J.; SueSee, B.; Hunt, D. Teachers’ Experiences of Teaching the Australian Health and Physical Education Health Benefits of Physical Activity Curriculum and the Need for Greater Reality Congruence. Curric. Perspect. 2022, 42, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PE Canada Model-Based Practice. Available online: https://phecanada.ca/activate/models-based-practice#:~:text=Models%2DBased%20Practice%20(MBP),affective%2C%20cognitive%2C%20psychomotor (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Kirk, D. Educational Value and Models-Based Practice in Physical Education. Educ. Philos. Theory 2013, 45, 973–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pill, S.; SueSee, B.; Davies, M. The Spectrum of Teaching Styles and Models-Based Practice for Physical Education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2023, 1356336X231189146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosston, M.; Ashworth, S. Teaching Physical Education, First Online Edition ed; Merrill Publishing Company Columbus: San Francisco, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D. Teacher-Student Relationships in Physical Education Activities in the Context of Inter-Subjectivity. Adv. Phys. Educ. 2022, 12, 332–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backman, E.; Barker, D. M. Re-Thinking Pedagogical Content Knowledge for Physical Education Teachers – Implications for Physical Education Teacher Education. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2020, 25, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L. E.; Stodden, D. F.; Barnett, L. M.; Lopes, V. P.; Logan, S. W.; Rodrigues, L. P.; D’Hondt, E. Motor Competence and Its Effect on Positive Developmental Trajectories of Health. Sport. Med. 2015, 45, 1273–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubans, D. R.; Foster, C.; Biddle, S. J. H. A Review of Mediators of Behavior in Interventions to Promote Physical Activity among Children and Adolescents. Prev. Med. (Baltim). 2008, 47, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stodden, D. F.; Langendorfer, S. J.; Goodway, J. D.; Roberton, M. A.; Rudisill, M. E.; Garcia, C.; Garcia, L. E. A Developmental Perspective on the Role of Motor Skill Competence in Physical Activity: An Emergent Relationship. Quest 2008, 60, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberger, M.; Suesee, B. Effects of the Reciprocal Teaching Style on Skill Acquisition, Verbal Interaction and Ability to Analyse in Fifth Grade Children in Physical Education. In The Spectrum of Teaching Styles in Physical Education; SueSee, B., Hewitt, M., Pill, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicilia, A.; Brown, D. Revisiting the Paradigm Shift from the versus to the Non-versus Notion of Mosston’s Spectrum of Teaching Styles in Physical Education Pedagogy: A Critical Pedagogical Perspective. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2008, 13, 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rink, J. E. Measuring Teacher Effectiveness in Physical Education. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2013, 84, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moy, B.; Renshaw, I.; Davids, K.; Brymer, E. Preservice Teachers Implementing a Nonlinear Physical Education Pedagogy. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2019, 24, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J. Y. Nonlinear Learning Underpinning Pedagogy: Evidence, Challenges, and Implications. Quest 2013, 65, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, V.; Ries, F.; Pires, F.; Caune, A.; Heszteráné Ekler, J.; Emeljanovas, A.; Valantiniene, I. The Relationship between Teaching Styles and Motivation to Teach among Physical Education Teachers. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2012, 11, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- SueSee, B.; Barker, D. M. Self-Reported and Observed Teaching Styles of Swedish Physical Education Teachers. Curric. Stud. Heal. Phys. Educ. 2019, 10, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrmpas, I.; Chen, S.; Pasco, D.; Digelidis, N. Greek Preservice Physical Education Teachers’ Mental Models of Production and Reproduction Teaching Styles. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2018, 25, 544–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinides, P.; Antoniades, O. Preservice Physical Education Teachers’ Use of Reproduction and Production Teaching Styles. Eur. J. Educ. Pedagog. 2022, 3, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Leung, R.; Liu, W.; Bian, W. Learning Outcomes Taught by Three Teaching Styles in College Fundamental Volleyball Classes. Clin. Kinesiol. 2009, 63, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- El Khouri, F. B.; de Meira Junior, C. M.; Rodrigues, G. M.; de Miranda, M. L. J. Effects of Command and Guided Discovery Teaching Styles on Acquisition and Retention of the Handstand. Rev. Bras. Educ. Física e Esporte 2020, 34, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuellar-Moreno, M.; Caballero-Juliá, D. Student Perceptions Regarding the Command and Problem Solving Teaching Styles in the Dance Teaching and Learning Process. Res. Danc. Educ. 2019, 20, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkash, E.; Zayed, W.; Bali, N. The Effect of Using the Two Competitive Teaching Styles and Stations on Learning Some Basic Football Skills for Physical Education Students. Phys. Educ. Students 2022, 26, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigueros, R.; Mínguez, L. A.; González-Bernal, J. J.; Jahouh, M.; Soto-Camara, R.; Aguilar-Parra, J. M. Influence of Teaching Style on Physical Education Adolescents’ Motivation and Health-Related Lifestyle. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klos, L.; Feil, K.; Eberhardt, T.; Jekauc, D. Interventions to Promote Positive Affect and Physical Activity in Children, Adolescents and Young Adults—A Systematic Review. Sports 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behzadnia, B.; Mohammadzadeh, H.; Ahmadi, M. Autonomy-Supportive Behaviors Promote Autonomous Motivation, Knowledge Structures, Motor Skills Learning and Performance in Physical Education. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 38, 1692–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidou, K.; Grassinger, R.; Lytrosygouni, E.; Ourda, D. Teaching Style, Motivational Climate, and Physical Education: An Intervention Program for Enhancing Students’ Intention for Physical Activity. Phys. Educ. 2022, 79, 514–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melguizo-Ibáñez, E.; González-Valero, G.; Badicu, G.; Filipa-Silva, A.; Clemente, F. M.; Sarmento, H.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; Ubago-Jiménez, J. L. Mediterranean Diet Adherence, Body Mass Index and Emotional Intelligence in Primary Education Students—An Explanatory Model as a Function of Weekly Physical Activity. Children 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruissen, G. R.; Zumbo, B. D.; Rhodes, R. E.; Puterman, E.; Beauchamp, M. R. Analysis of Dynamic Psychological Processes to Understand and Promote Physical Activity Behaviour Using Intensive Longitudinal Methods: A Primer. Health Psychol. Rev. 2022, 16, 492–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018-2030: More Active People for a Healthier World; World Health Organization, 2019.

- Ruiz-Montero, P. J.; Chiva-Bartoll, O.; Baena-Extremera, A.; Hortigüela-Alcalá, D. Gender, Physical Self-Perception and Overall Physical Fitness in Secondary School Students: A Multiple Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monacis, D.; Trecroci, A.; Invernizzi, P. L.; Colella, D. Can Enjoyment and Physical Self-Perception Mediate the Relationship between BMI and Levels of Physical Activity? Preliminary Results from the Regional Observatory of Motor Development in Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallen, J.; Andrä, C.; Ludyga, S.; Mücke, M.; Herrmann, C. School Children’s Physical Activity, Motor Competence, and Corresponding Self-Perception: A Longitudinal Analysis of Reciprocal Relationships. J. Phys. Act. Heal. 2020, 17, 1083–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T. C.; Wang, C. X.; Tao, B. Le; Sui, H. R.; Yan, J. The Relationship between Physical Activity and Prosocial Behavior of College Students: A Mediating Role of Self-Perception. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0271759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crane, J. R.; Foley, J. T.; Temple, V. A. The Influence of Perceptions of Competence on Motor Skills and Physical Activity in Middle Childhood: A Test of Mediation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babic, M. J.; Morgan, P. J.; Plotnikoff, R. C.; Lonsdale, C.; White, R. L.; Lubans, D. R. Physical Activity and Physical Self-Concept in Youth: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2014, 44, 1589–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardid, F.; De Meester, A.; Tallir, I.; Cardon, G.; Lenoir, M.; Haerens, L. Configurations of Actual and Perceived Motor Competence among Children: Associations with Motivation for Sports and Global Self-Worth. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2016, 50, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairney, J.; Dudley, D.; Kwan, M.; Bulten, R.; Kriellaars, D. Physical Literacy, Physical Activity and Health: Toward an Evidence-Informed Conceptual Model. Sport. Med. 2019, 49, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Lee, K.; Kwon, S. Basic Psychological Needs, Exercise Intention and Sport Commitment as Predictors of Recreational Sport Participants’ Exercise Adherence. Psychol. Heal. 2020, 35, 916–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Murcia, J. A.; Ramis-Claver, J.; Ruiz-González, L.; Rodrigues, F.; Hernández, E. H. Longitudinal Perspective of Autonomy Support on Habitual Physical Activity of Adolescents. Int. J. Sport. Sci. Coach. 2022, 17, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabra, P.; González-García, L.; Castillo, I.; Duda, J. L.; Balaguer, I. Motivational Antecedents of Young Players’ Intentions to Drop Out of Football during a Season. Sustain. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, L. R.; Cinelli, R. L.; Cotton, W.; Morris, S.; Galy, O.; Caillaud, C. The Barriers to and Facilitators of Physical Activity and Sport for Oceania with Non-European, Non-Asian (ONENA) Ancestry Children and Adolescents: A Mixed Studies Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, W. H.; Yang, J. Y. High-School Students’ Continuous Engagement in Taekwondo Activity: A Model of the Self-Determination Theory-Based Process. European Journal of Psychology Open. 2022, 81, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, A.; Munk, N.; Stanton-Nichols, K. A. Applying Theory to Overcome Internal Barriers for Healthy Behavior Change in Adults with Intellectual Disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2021, 26, 718–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sum, R. K. W.; Wallhead, T.; Wang, F.-J.; Choi, S.-M.; Li, M.-H.; Liu, Y. Effects of Teachers’ Participation in Continuing Professional Development on Students’ Perceived Physical Literacy, Motivation and Enjoyment of Physical Activity. Rev. Psicodidáctica (English ed.) 2022, 27, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Sweeney, M. R.; McGrane, B. The Effect of a Games-Based Intervention on Wellbeing in Adolescent Girls. Health Educ. J. 2022, 81, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Viladrich, C.; Cruz, J. Examining the Relationship between Academic Stress and Motivation toward Physical Education within a Semester: A Two-Wave Study with Chinese Secondary School Students. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisterer, S.; Paschold, E. Increased Perceived Autonomy-Supportive Teaching in Physical Education Classes Changes Students’ Positive Emotional Perception Compared to Controlling Teaching. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invernizzi, P. L.; Crotti, M.; Bosio, A.; Cavaggioni, L.; Alberti, G.; Scurati, R. Multi-Teaching Styles Approach and Active Reflection: Effectiveness in Improving Fitness Level, Motor Competence, Enjoyment, Amount of Physical Activity, and Effects on the Perception of Physical Education Lessons in Primary School Children. Sustainability 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatni, A. Effect of Learning Approach and Motor Skills on Physical Fitness. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2022, 22, 2273–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elumalai, G.; Chinanapan, K.; Choeibuakaew, W.; Iqbal, D. R.; Abadi, F. H. Can Model-Based Approach in Physical Education Improve Physical Fitness, Academic Performance, and Enjoyment among Pupils? A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Hum. Mov. Sport. Sci 2022, 10, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colella, D.; Monacis, D.; Massari, F. E. Assessment of Motor Performances in Italian Primary School Children: Results of SBAM Project. Adv. Phys. Educ. 2019, 9, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, T. J.; Bellizzi, M. C.; Flegal, K. M.; Dietz, W. H. Establishing a Standard Definition for Child Overweight and Obesity Worldwide: International Survey. BMJ 2000, 320, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, B.; Cohen, Y.; Lustig, G.; Lander, Y.; Yaaron, M.; Ayalon, J. Tracking of Physical Fitness Components in Boys and Girls from the Second to Sixth Grades. Am. J. Hum. Biol. Off. J. Hum. Biol. Counc. 2001, 13, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, J. J. R.; Mood, D.; Disch, J.; Kang, M. Measurement and Evaluation in Human Performance, 5E; Human Kinetics, 2015.

- Ruiz, J. R.; Castro-Piñero, J.; España-Romero, V.; Artero, E. G.; Ortega, F. B.; Cuenca, M. M.; Jimenez-Pavón, D.; Chillón, P.; Girela-Rejón, M. J.; Mora, J.; Gutiérrez, A.; Suni, J.; Sjöström, M.; Castillo, M. J. Field-Based Fitness Assessment in Young People: The ALPHA Health-Related Fitness Test Battery for Children and Adolescents. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colella, D.; Morano, M.; Bortoli, L.; Robazza, C. A Physical Self-Efficacy Scale for Children. Soc. Behav. Personal. An Int. J. 2008, 36, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraro, A.; Young, M.; Robazza, C. A Contribution to the Validation of the Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale in an Italian Sample. Soc. Behav. Personal. an Int. J. 2008, 36, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, Revised.; Academic press: New York, NY, US, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, K.; Kingston, K.; Sproule, J. Effects of Different Teaching Styles on the Teacher Behaviours That Influence Motivational Climate and Pupils’ Motivation in Physical Education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2005, 11, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Caja, E.; Weiss, M. R. Predictors of Intrinsic Motivation among Adolescent Students in Physical Education. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2000, 71, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudley, D.; Okely, A.; Pearson, P.; Cotton, W. A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Physical Education and School Sport Interventions Targeting Physical Activity, Movement Skills and Enjoyment of Physical Activity. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2011, 17, 353–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diloy-Peña, S.; García-González, L.; Sevil-Serrano, J.; Sanz-Remacha, M.; Abós, Á. Motivating Teaching Style in Physical Education: How Does It Affect the Experiences of Students? Apunt. Educ. Física y Deport. 2021, 144, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatoupis, C.; Emmanuel, C. The Effects of Two Disparate Instructional Approaches on Student Self-Perceptions in Elementary Physical Education. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2003, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Pérez, S.; León-Del-barco, B.; Fernandez-Rio, J.; González-Bernal, J. J.; Gallego, D. I. Linking Cooperative Learning and Emotional Intelligence in Physical Education: Transition across School Stages. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moy, B.; Renshaw, I.; Davids, K. The Impact of Nonlinear Pedagogy on Physical Education Teacher Education Students’ Intrinsic Motivation. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2016, 21, 517–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.; Espada, M. Knowledge, Education and Use of Teaching Styles in Physical Education. Int. J. Instr. 2021, 14, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B. V. F. da; Santos, R. H. dos; Savarezzi, G. R.; de Souza, M. T.; Gimenez, R. Teaching Strategies in Physical Education: A Confrontation between Directive and Indirective Styles in Volleyball Learning. J. Phys. Educ. 2020, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khouri, F. B.; de Meira Junior, C. M.; Rodrigues, G. M.; de Miranda, M. L. J. Effects of Command and Guided Discovery Teaching Styles on Acquisition and Retention of the Handstand. Rev. Bras. Educ. Física e Esporte 2020, 34, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Total Sample | ||||||||||||

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | ||||||

| Control | Age | 31 | 9,23 | ,42 | 31 | 9,23 | ,66 | 62 | 9,23 | ,55 | ||||

| Weight | 31 | 38,10 | 8,58 | 31 | 40,00 | 13,25 | 62 | 39,05 | 11,11 | |||||

| Height | 31 | 1,3790 | ,074 | 31 | 1,38 | ,073 | 62 | 1,38 | ,073 | |||||

| BMI | 31 | 19,87 | 3,59 | 31 | 20,45 | 5,03 | 62 | 20,16 | 4,34 | |||||

| Experimental | Age | 31 | 9,39 | ,61 | 31 | 9,03 | 1,85 | 62 | 9,21 | 1,38 | ||||

| Weight | 31 | 37,74 | 11,15 | 31 | 37,81 | 11,16 | 62 | 37,77 | 11,06 | |||||

| Height | 31 | 1,370 | ,084 | 31 | 1,37 | ,080 | 62 | 1,37 | ,081 | |||||

| BMI | 31 | 19,78 | 4,17 | 31 | 19,78 | 4,80 | 62 | 19,78 | 4,46 | |||||

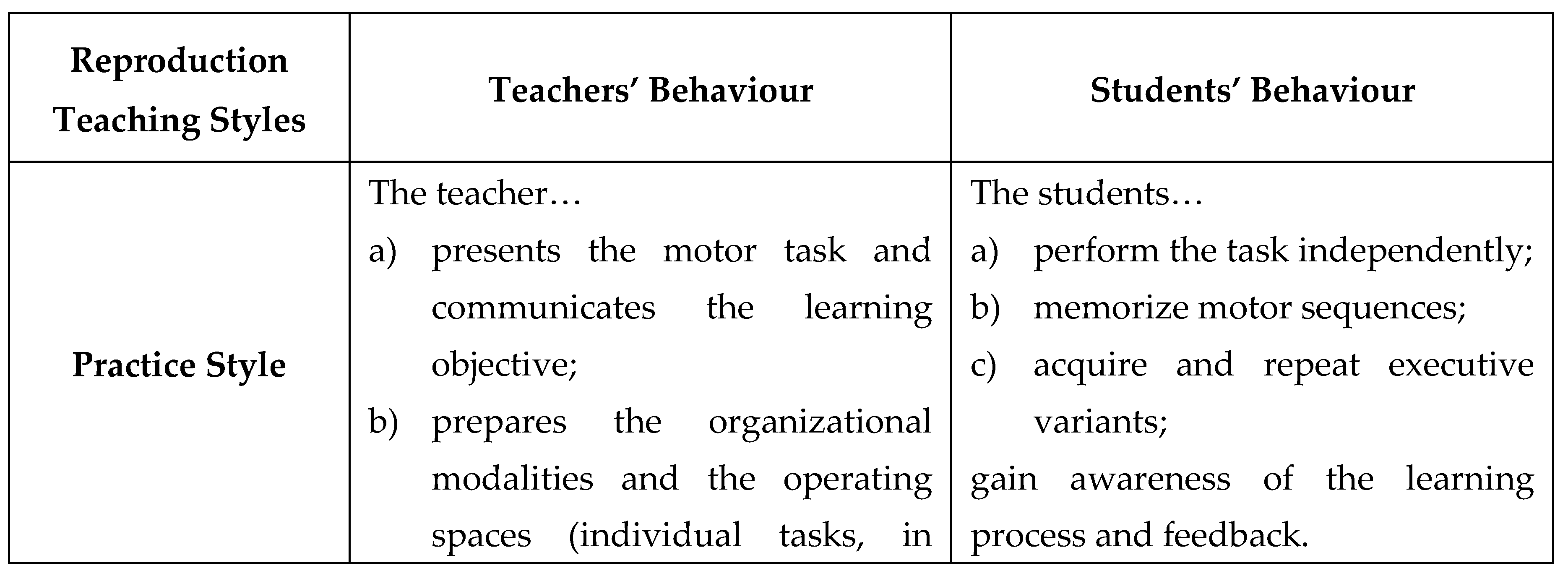

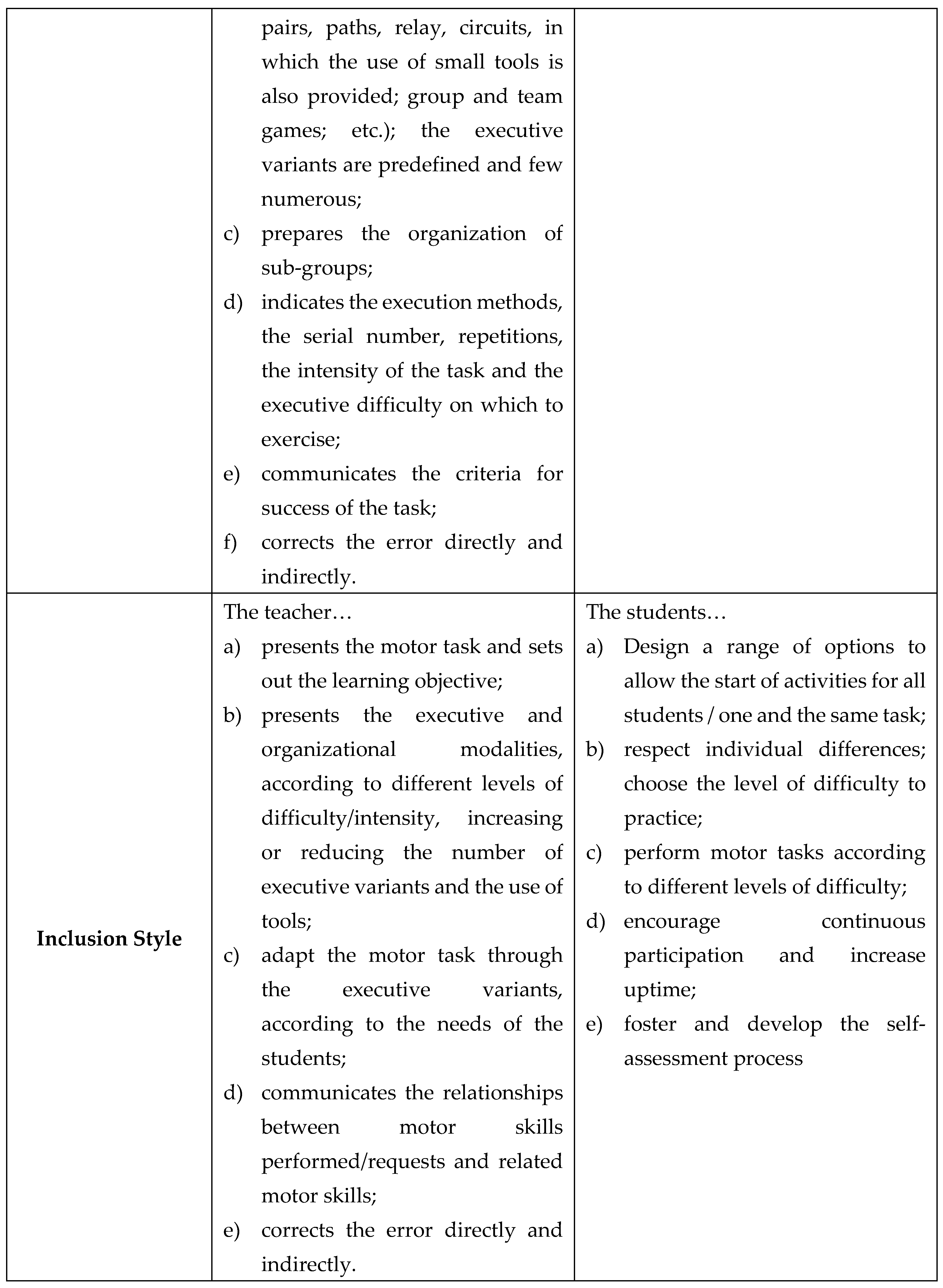

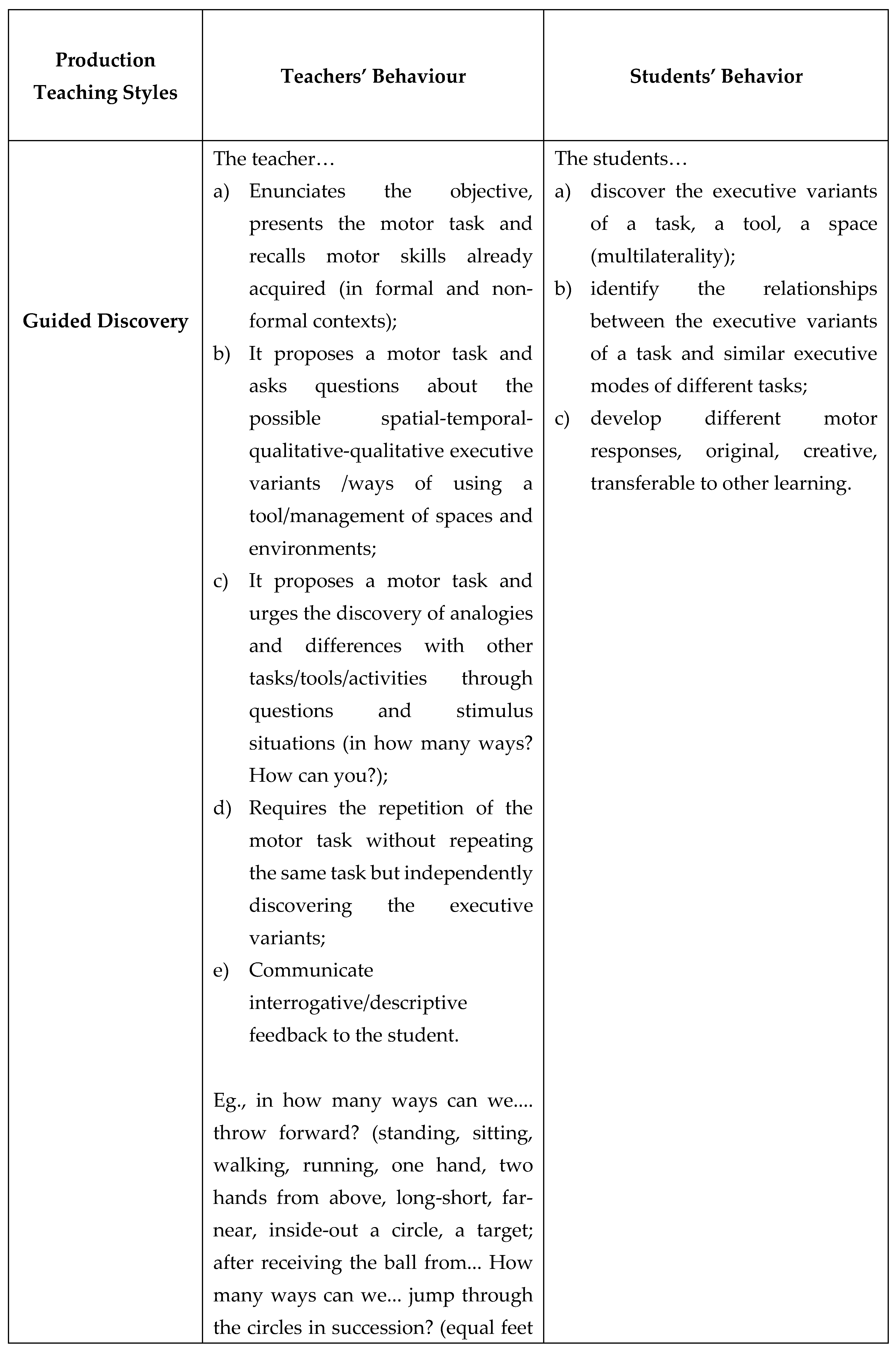

| Topics | Aims | Contents and Organizational Modalities | Teaching Styles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motor skills and small tools: the space-time executive variants | ➣ Perform basic motor skills and executive variants with the use of small tools; ➣ Discover and distinguish the specific use of tools in PE; ➣ Distinguish the rules of the proposed activities; |

Individual and in pairs motor tasks with small tools (circle and ball,) considering the dynamic/stationary relation between them; | • Guided-discovery style; • Practice style; |

| Group games and space-time orientation | ➣ Anticipate the course and outcome of an action; ➣ Perform and vary motor skills in minimum time; ➣ Organize a group game; ➣ Compare and apply different rules; |

Ball games preparatory to team game; | • Practice style; • Guided-disvoery style; • Divergent discovery style; |

| Expressiveness and dramatization | ➣ Express emotions through body and movement; ➣ Produce unusual and creative gesture; ➣ Discover the rules of mimic-gestural communication; ➣ Represent and graphically rework the body-motor experience lived; |

Symbolic interpretation of emotions through gestures and postures; Games of imitation, representation and body expression. | • Guided-disvovery style; • Divergent discovery style; |

| Motor coordination | ➣ Combine motor skills according to spatial and temporal constraints; ➣ Perform motor skills according to strength and speed parameters; ➣ Analyze, self-assess and verbalize the motor experience; |

Tasks in pairs of motor combination and spatial-temporal differentiation also with the use of small tools; Paths with specific interactions of basic motor skills and executive variants; | • Practice style; • Inlcusion style; • Guided-discovery style; • Divergent doscovery style; |

| Independent T-Test (t0) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levene’s Test | t-Test for Equality of Means | ||||||||||||||||

| 95% CI | |||||||||||||||||

| Group | N | Mean | SD | Mean SE | F | Sign. | t | gl | Sig. | Mean Dif. | SE Dif | Lower | Upper | ||||

| SLJ | CG | 62 | 1,17 | ,25 | ,032 | ,003 | ,953 | 1,196 | 122 | ,234 | ,05 | ,045 | -,03 | ,14 | |||

| EG | 62 | 1,12 | ,25 | ,031 | |||||||||||||

| MBT | CG | 62 | 3,9 | ,94 | ,12 | ,017 | ,897 | -1,320 | 122 | ,189 | -,23 | ,175 | -,57 | ,11 | |||

| EG | 62 | 4,23 | ,99 | ,12 | |||||||||||||

| 20m | CG | 62 | 5,31 | ,63 | ,08 | ,016 | ,899 | 2,416 | 122 | ,117 | ,27 | ,11 | ,048 | ,49 | |||

| EG | 62 | 5,04 | ,61 | ,07 | |||||||||||||

| PSP | CG | 62 | 16,65 | 3,40 | ,43 | ,341 | ,560 | ,923 | 122 | ,358 | ,53 | ,57 | -,60 | 1,67 | |||

| EG | 62 | 16,11 | 2,98 | ,38 | |||||||||||||

| PACES | CG | 62 | 35,24 | 5,10 | ,64 | 1,173 | ,281 | -2,520 | 122 | ,113 | -2,42 | ,96 | -4,33 | -,52 | |||

| EG | 62 | 37,67 | 5,61 | ,71 | |||||||||||||

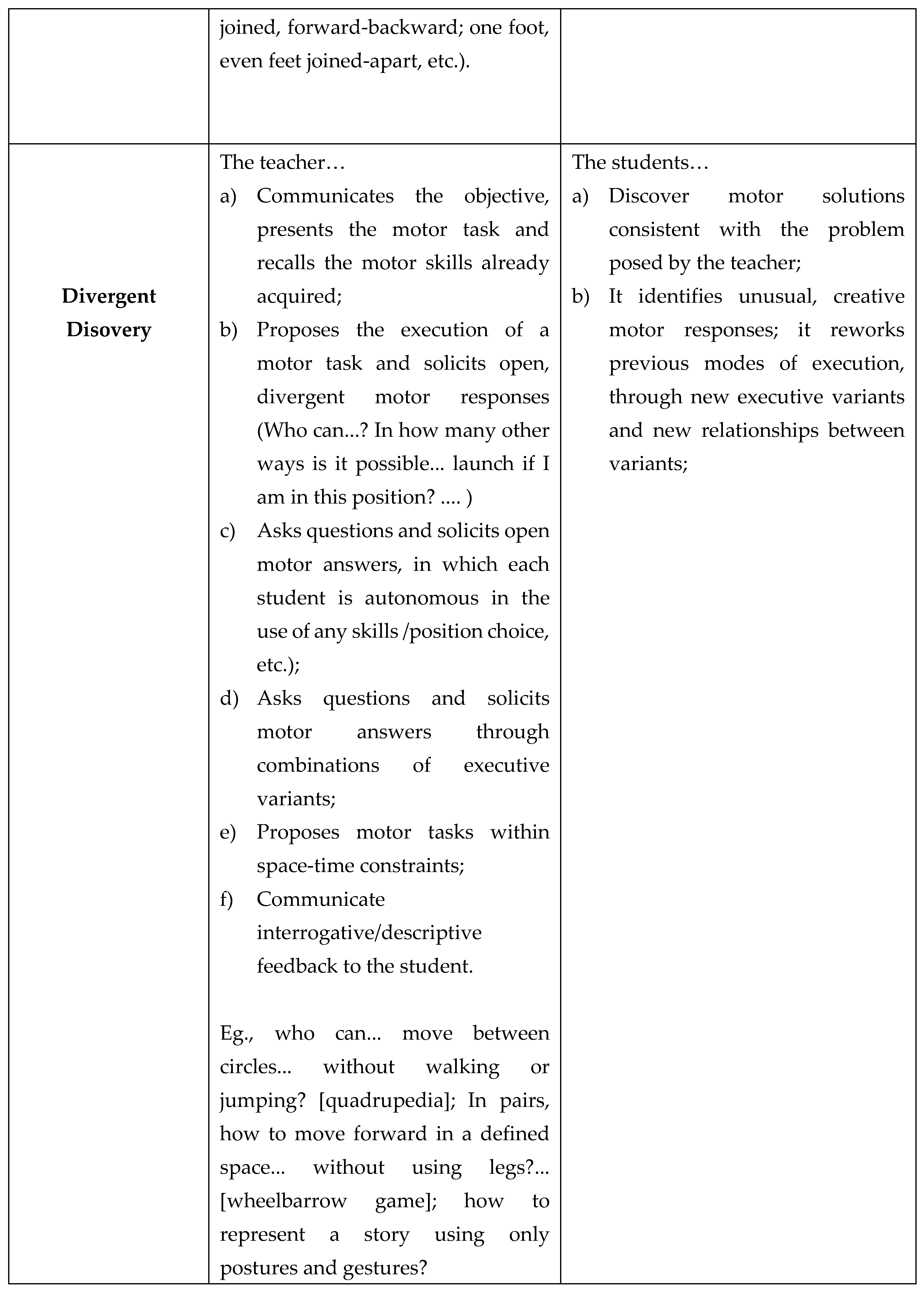

| Differences pre-post intervention and interaction effects | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | Experimental Group (n=62) | Control Group (n=62) | Intervention x time p-value | η2 | |||||||||||

| t0 | t1 | t0 | t1 | ||||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||||||||

| SLJ | 1,12 | ,25 | 1,19* | ,23 | 1,17 | ,25 | 1,22* | ,23 | ,325 | ,016 | |||||

| MBT | 4,23 | ,99 | 4,34* | 1,01 | 3,99 | ,94 | 4,21* | ,99 | ,143 | ,035 | |||||

| 20m | 5,04 | ,61 | 4,82* | ,67 | 5,31 | ,63 | 4,85* | ,61 | ,005 | ,124 | |||||

| PSP | 16,11 | 2,99 | 17,68* | 2,69 | 16,65 | 3,40 | 16,21 | 2,93 | ,000 | ,225 | |||||

| Enjoyment | 37,67 | 5,61 | 39,73* | 4,50 | 35,24 | 5,10 | 35,85 | 5,08 | ,040 | ,057 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).