1. Introduction

The 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was first recognized in December 2019 in Wuhan, the capital of China's Hubei province. Since then, the disease has spread worldwide, leading to a coronavirus pandemic[

1]. In January 2020, it was recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a major public health concern. COVID-19 has led to a global health crisis that is defining for our times and one of the greatest challenges to emerge since World War II. As a result of this sudden onset epidemic, governments and public health authorities urgently needed guidance and useful information on effective interventions to protect the health of the population.

Given the paucity of data in the existing academic literature on clinically manifested peripartum depression among women who gave birth during the COVID-19 pandemic, we set out to assess the risk of developing peripartum depressive disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with the risk among women who gave birth before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The postpartum period represents a time of increased vulnerability for the development of psychiatric disorders[

2]. The potential impact of the pandemic on mental health should not be overlooked, especially among vulnerable populations [

3,

4]. According to the World Health Organization, approximately 10% of parturients and 13% of postpartum women experience some form of mental disorder, mainly depression [

5]. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, maternal distress may be exacerbated by concerns and fears about the risk of infection or hospitalization due to the coronavirus, given that perinatal morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19 have been documented [

6,

7].

Postpartum depression is defined in psychiatric nomenclature as a major depressive disorder with specific onset in the first month after parturition, with the possibility of extending the time interval up to one year [

8]. It is considered a major public health problem as it affects both mother and child, has a high prevalence globally, ranging from 10% to 20% in most studies. The term postnatal depression is generically used in literature to designate the picture of depressive symptoms, with onset in the period following childbirth and whose aetiology is related to childbirth, as well as to hormonal (physiological), psychological, environmental or social aspects, which occur in temporal proximity to the moment of birth.

Women who develop postnatal depression are at greater risk of relapsing during subsequent pregnancies and of developing major depressive disorder outside the perinatal period. Studies in recent years have shown that the nature of the early mother-infant relationship in the context of postpartum depression is predictive of the child's cognitive, emotional and social development [

9].

Previous publications have noted an increased likelihood of depressive symptoms among pregnant or postpartum women, but these studies have been limited by the relatively small sample sizes of the patients included, as well as the individual particularities of each country in which they were conducted [

10,

11]. The extent to which parturients were emotionally affected by the pandemic remains unclear and problematic. It is therefore necessary to clarify which women are more at risk of being affected by peripartum depression. It is also important that the factors involved in the onset of mental distress are identified to help develop effective screening and prevention strategies among vulnerable populations.

The aim of this study was to assess the mental health status of postpartum women in pandemic times, and to investigate potential associations between the symptoms of depressive disorder onset in close temporal proximity to the time of birth and the socio-demographic conditions, health status and obstetric particularities of the patients. The 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was first recognized in December 2019 in Wuhan, the capital of China's Hubei province. Since then, the disease has spread worldwide, leading to a coronavirus pandemic [

1]. In January 2020, it was recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a major public health concern. COVID-19 has led to a global health crisis that is defining for our times and one of the greatest challenges to emerge since World War II. As a result of this sudden onset epidemic, governments and public health authorities urgently needed guidance and useful information on effective interventions to protect the health of the population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Studied Population

The study is a cross-sectional survey conducted from 01.03.2020 to 01.03.2023, during the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic, based on a retrospective evaluation of 860 postpartum women. The study was carried out in the Obstetrics and Gynaecology Clinical Sections I and II of the "Pius Brinzeu" County Emergency Hospital from Timisoara, Romania.

The participants in this study were mothers over 18 years of age, who had given birth in the last year from the date of completion of the survey and who expressed an interest in this topic. Prior informed consent was obtained for each patient. Mothers under the age of 18 and those who had not given birth in the last year since the questionnaire was completed were excluded.

The screening tool used to assess symptoms of postpartum depression was the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Rating Scale (EPDS) questionnaire. The questionnaire was completed both in the Obstetrics and Gynaecology Clinical Departments I and II and online using Google Forms.

In order to highlight the particularities of postpartum depression, as well as the factors favouring this pathology, in the patients included in this study, the following parameters were also taken into account: Age; marital status; background; level of education; working conditions (risk at work); socio-economic conditions; health status; personal pathological history; parity; method of obtaining pregnancy; type of birth, under the recommendation of the medical consultant; mother's wishes regarding the type of birth; number of miscarriages; number of abortions upon request.

2.2. Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale Questionnaire

Depression is a pathology where psychometric assessment is particularly useful in confirming the diagnosis.

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Rating Scale (EPDS) questionnaire is one of the most widely used screening tools for assessing symptoms of perinatal depression and anxiety. It is a simple instrument that assesses emotional experiences over the past seven days using 10 Likert scale questions, is easy to fill in and interpret, requires no specialist psychiatric expertise and could easily be incorporated into the health care services offered to all women in the postnatal period[

12].

This self-report tool was developed and tested in health centres in Edinburgh and Livingston (UK) by Cox, Holden and Sagovskyin 1987 to help detect women suffering from postnatal depression. Since its inception, the EPDS has been adapted for use in several countries and has become the most widely used tool for assessing postpartum depression.

Ratings of responses to the 10 questions are summed, and the resulting score can assess the likelihood that the patient has clinical depression. The EPDS scale is composed of three structural factors: the "depression" factor through questions 1, 2, 8; the "anxiety" factor through questions 3, 4, 5 and the "suicide" factor through question 10. A score >10 betrays a possible depression (minor depressive disorder), a score ≥13 suggests a major depressive disorder (moderate to severe) [

12,

13,

14].

The EPDS scale can provide stable results, especially when assessments are done repeatedly. In comparison with a clinical diagnostic interview, the EPDS demonstrated the following psychometric properties: a specificity of 78%, a sensitivity of 86%, and a positive predictive value of 73% for women scoring >10. Validity studies show that the scale can correctly identify 92.3% of women with postpartum depression.

2.3. Statistical Assessment

The collected data were introduced in Excel format and statistically processed with the SPSSv.17 software package.

Nominal variables were represented as frequency tables for which percentage distributions (pie) were plotted and associated with χ2 (Chi square) test of concordance. For the numeric variables, indicators of central tendency (mean, median) and dispersion (standard deviation and standard error of the mean) were calculated, and for the study of the association between them, Spearman's nonparametric linear correlation analysis was carried out with the help of which we calculated correlation coefficients and probability values that give us the significance of the correlation (p-values must be below 0. 05 for the association to be significant). For comparisons between 2 sets of numerical variables, the Mann-Whitney U nonparametric test was used, and for comparisons between more than 2 sets, the Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test was applied.

3. Results

The study involved 860 women in their first year after childbirth. The average age of the mothers was 28.52 years, with the youngest being 18 years old and the oldest being 45 years old. By marital status, 86.7% (746) of mothers were married, 11.4% (98) were cohabiting and 1.9% (16) were single. If we consider the background of the mothers, 69.5% (598) came from urban areas and 30.5% (262) from rural areas. Considering the level of education, 59.2% (509) have higher education, 32.2% (277) have graduated from high school and the remaining 8.6% (74) have no secondary education. Regarding the socio-economic conditions of the mothers, it appears that 59% (507) of the total patients have a good standard of living, 19.4% (167) have a very good standard of living, while 18.6% (160) have satisfactory conditions and the remaining 3% (26) have poor living conditions. Looking at workplace hazard, 8.4% (72) have high workplace hazard, 22.7% (195) have medium hazard, while the majority, 69% (593) have low workplace hazard. In terms of health status, 79.4% (683) rated their health as good, 19.5% (168) as satisfactory and only 1% (9) as poor. Regarding the distribution of patients by parity, 49.1% (422) of the mothers included in the study were primiparous, 50.9% (438) were multiparous. According to the number of miscarriages, 80.1% (689) had no miscarriage in their personal history, 15.1% (130) had 1 miscarriage, 4% (34) with 2 miscarriages, 0.6% (5) with 3 miscarriages and only 0.2% (2) with 4 miscarriages in their personal obstetric history. If we consider the number of abortions performed upon request in the history of the patients involved in the study, 87.2% (750) had no abortion on request, 9% (77) with 1 abortion on request, 2.7% (23) with 2 abortions on request, 0.9% (8) with 3 abortions on request, 0.2% (2) with 5 abortions on request. Considering the method of achieving pregnancy, in 95.8% (824) of cases pregnancy was achieved naturally, in 1.2% (10) of cases by in vitro fertilisation, and in 3% (26) of cases with previous treatment. According to parity, 65.2% (561) were primiparous, 28.1% (242) secondary, 5.2% (45) tertiparous, 1.3% (11) quarteparous, 0.1% (1) quintile.

Following the assessment of the clinical status of the women, using the Edinburgh Psychiatric Postnatal Depression Rating Scale (EPDS), 54.2% (466 patients) had major depressive disorder; 15.6% (134) had minor depressive disorder and 30.2% (260 patients) had no depressive disorder.

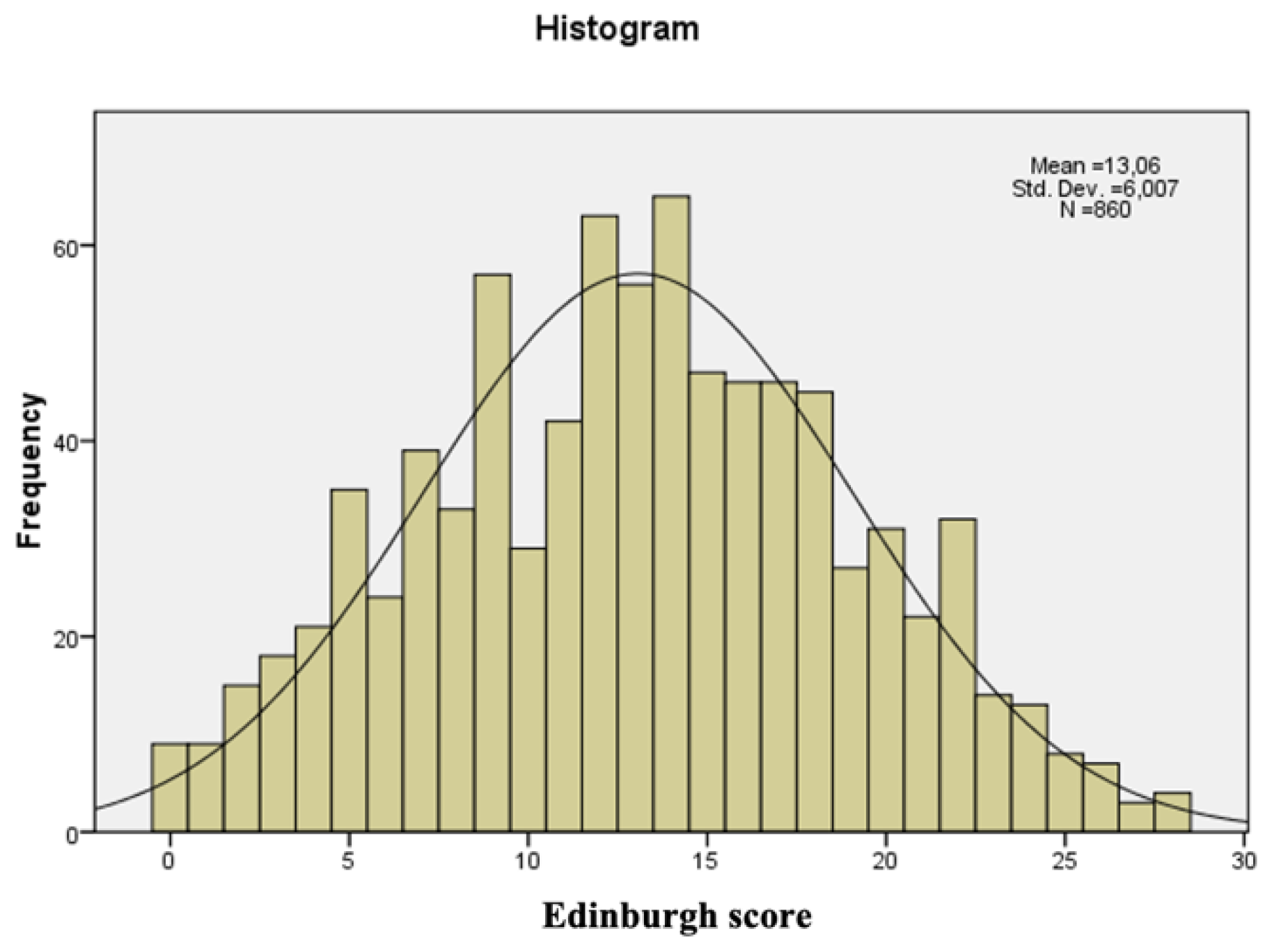

The recorded values of the Edinburgh score following completion of the questionnaire ranged from 0 to 28, with a mean score of 13.06. The maximum possible Edinburgh score of 30 was not recorded in this study. (

Figure 1)

Of the 860 patients, 57.7% (496) gave birth by caesarean section (C-section) and 42.3% (364) gave birth naturally. As for the mother's wishes regarding the type of birth, 71.9% (618) would have liked to give birth naturally and 28.1% (242) would have opted for C-section. A significant association was found between the mother's desire for future birth and the type of birth (Chi2 test, p<0.001), in other words, the obstetrician takes the mother's desire into account when determining the type of birth. The proportion of births by C-section for mothers who wanted C-section is significantly increased compared to that of C-sections for mothers who wanted natural birth.

A significant association was established between type of delivery and depressive disorder (Chi2 test, p=0.003). The proportion of mothers without depressive disorder is significantly increased among those who delivered naturally (Chi2 test, p=0.0012) and of those with major depressive disorder is significantly decreased for mothers who delivered naturally (Chi2 test, p=0.0041)(

Figure 2). The occurrence of postpartum depressive disorder is significantly influenced by type of delivery.

There was a significant association between type of birth and marital status (Chi2 test, p<0.001). Married mothers who gave birth by Caesarean section were significantly more numerous than those who gave birth naturally (Chi2 test, p=0.038). Those living in cohabitation who gave birth by Caesarean section were significantly fewer than those who gave birth naturally (Chi2 test, p=0.0011). Single mothers who gave birth by caesarean section are significantly more than those who gave birth naturally (Chi2 test, p=0.026).(

Table 1)

The association between type of birth and level of education is significant (Chi2 test, p<0.001). The proportion of mothers without higher education is significantly increased among those who gave birth naturally (Chi2 test, p<0.001), respectively, the proportion of mothers with higher education is significantly increased among those who gave birth by caesarean section (Chi2 test, p=0.012). (

Table 1)

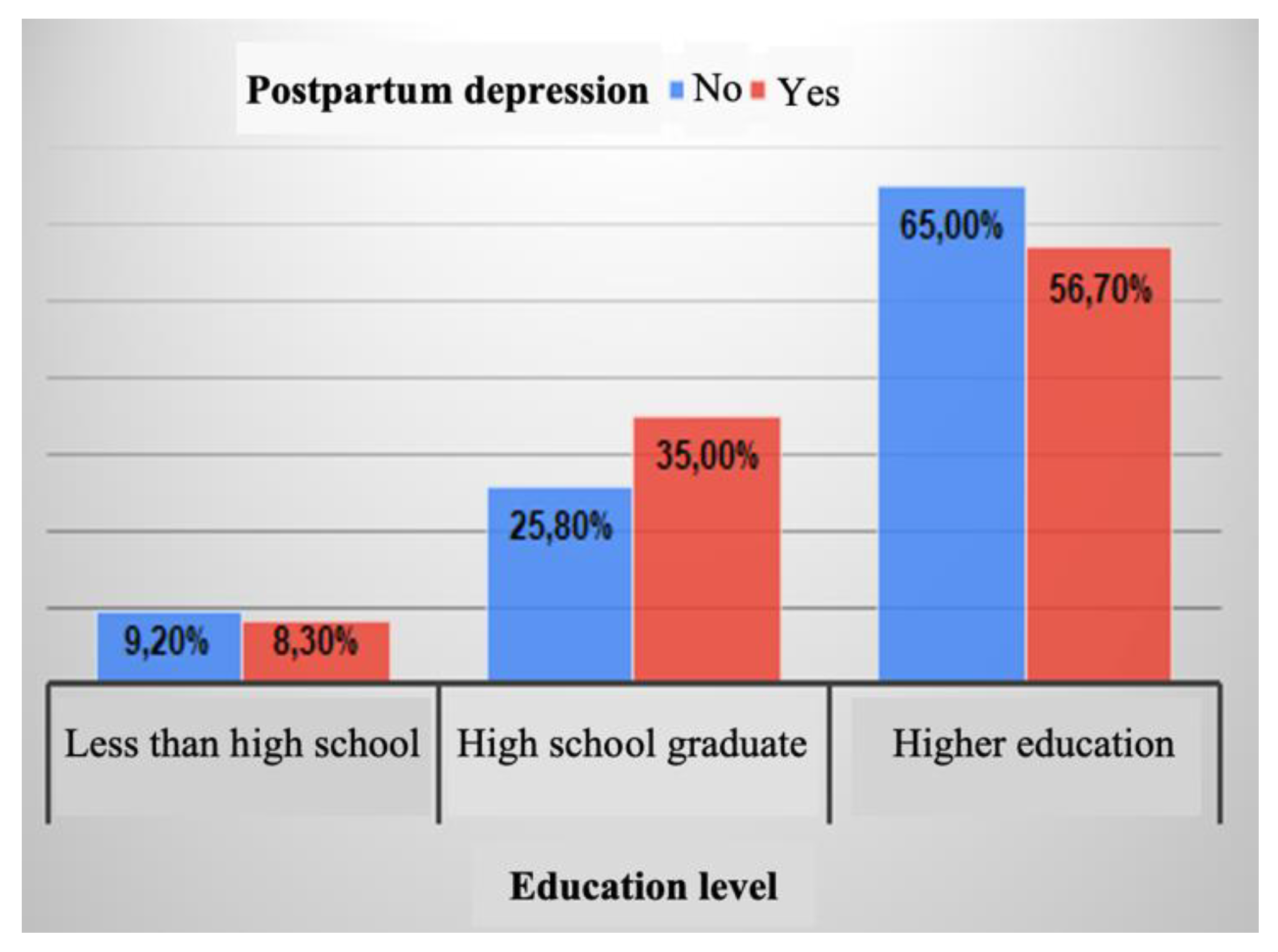

The proportion of mothers who have a high school education is significantly increased among those with postpartum depression (p=0.010), while the proportion of those with a college education is significantly increased among those without postpartum depressive disorder (p=0.028)(

Figure 3). The association is significant (Chi2 test, p=0.029).

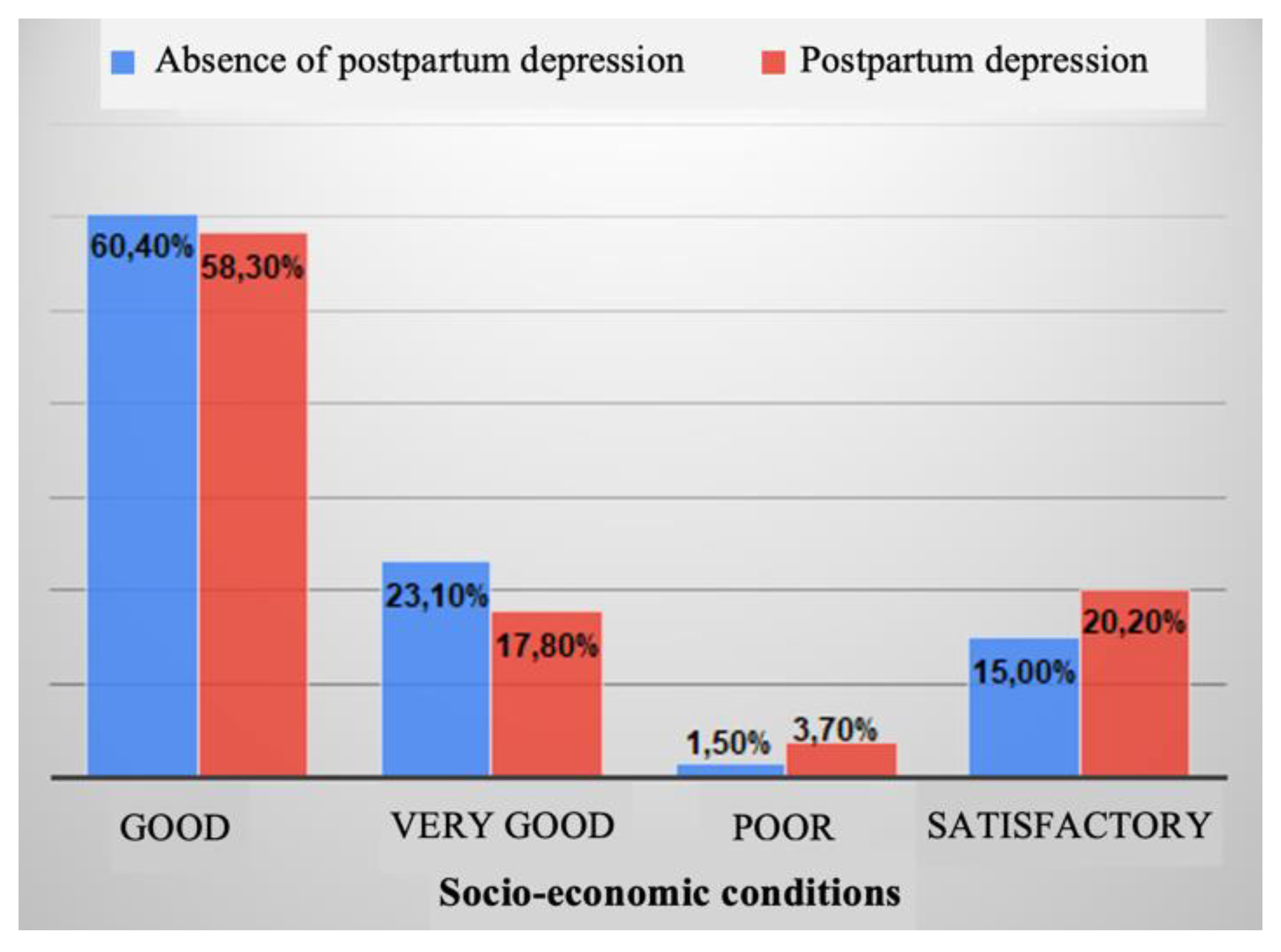

The association between depressive disorder and socio-economic conditions is significant (Chi2 test, p=0.046). The proportion of mothers suffering from postnatal depression is significantly increased among those with satisfactory or poor socio-economic conditions (

Figure 4).

The association between depressive disorder and health status is significant (Chi2 test, p<0.001). The proportion of mothers with depressive disorder is significantly increased among those with fair or poor health status (Chi2 test, p<0.001) (

Figure 5).

A direct, significant and weak correlation was found between the number of miscarriages and the number of births (Spearman correlation coefficient r=0.165, p<0.001) - women who have an increased number of miscarriages also have an increased number of births.

A direct, significant and weak correlation was found between the number of abortions on demand and the number of births (Spearman correlation coefficient r=0.142, p<0.001) - women who have an increased number of abortions on demand also have an increased number of births.

A direct, significant and weak correlation (Spearman correlation coefficient r=0.138, p=0.001) was found between the number of abortions on demand and the Edinburgh score - women who have an increased number of abortions on demand also have an increased Edinburgh score.

Maternal age is significantly lower for respondents with depressive disorder (Mann-Whitney U nonparametric test, p=0.025), indicating a possible association of younger age with the onset of postnatal depression (

Table 2 and

Figure 6).

Women with postnatal depressive disorder have a significantly increased number of abortions on demand (Mann-Whitney U nonparametric test, p=0.005).

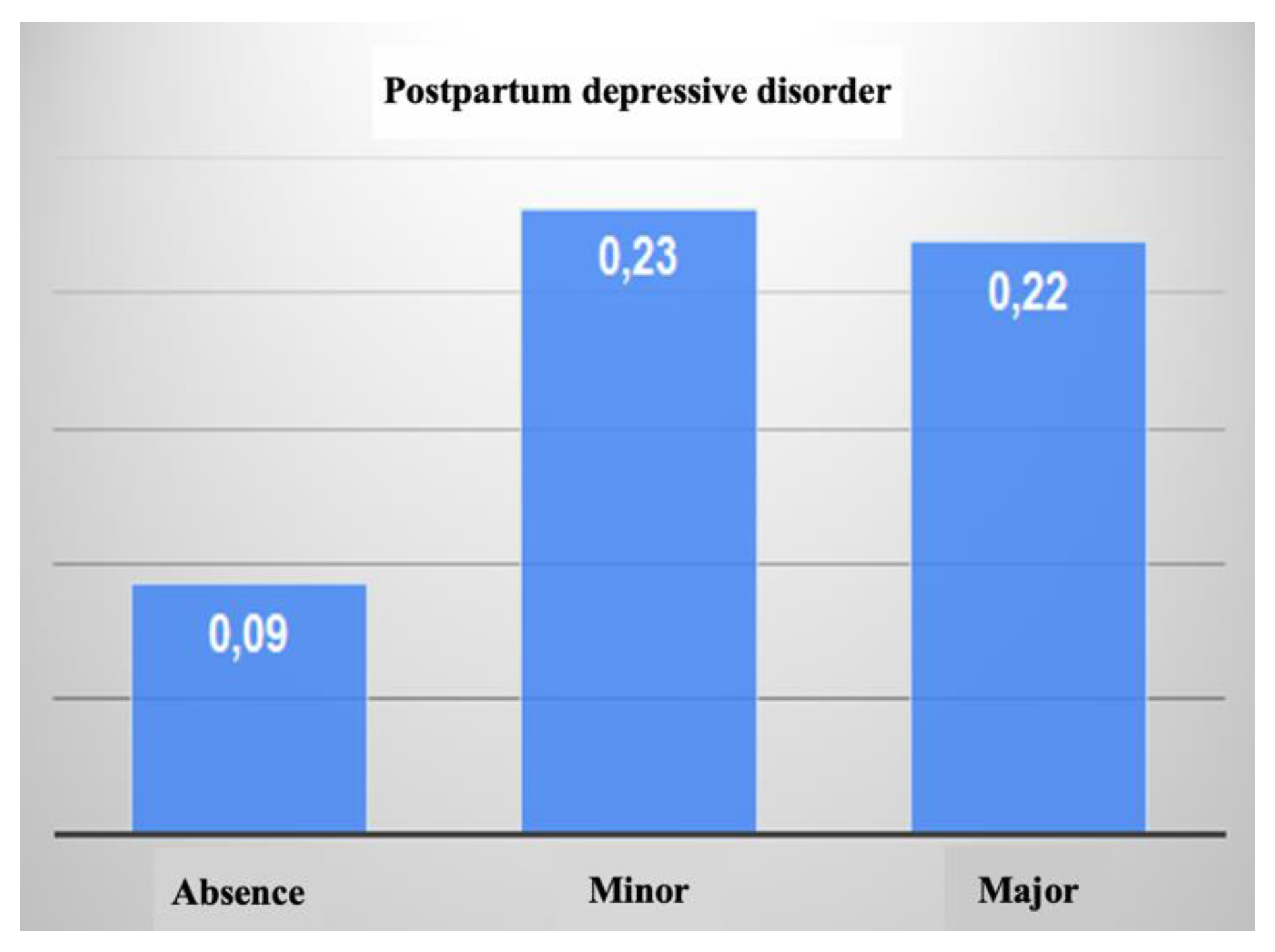

The number of abortions on demand is significantly increased among mothers with depressive disorder, both minor and major, therefore, the personal obstetric history of patients may be a factor in the development of postnatal depressive disorder. (Kruskall-Wallis nonparametric test, p=0.018) (

Table 2 and

Figure 7).

Mothers who gave birth by caesarean section have a significantly increased Edinburgh score (Mann-Whitney U nonparametric test, p=0.008), which means that they are more likely to develop depressive symptoms (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

The results of the study conducted during the period of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (COVID-19) showed that the prevalence of major postpartum depressive disorder was 54.2% (466 patients), while 15.6% (134) had minor depressive disorder in the first year after delivery. Comparing these results with those obtained in research conducted before the onset of the pandemic period shows an alarming increase in the prevalence of postpartum depression. The incidence of postpartum depressive disorder worldwide in the non-pandemic period was about 10% in developed countries and about 21-26% in developing countries [

15,

16]. Previous research has also found that during natural disasters that struck humanity, prevalence rates of mental disorders among postpartum women were significantly higher than those among the general population [

17]. Moreover, studies conducted in the pre-pandemic period have shown that in about 30% of patients with postnatal depressive disorder, recovery or resolution of depressive symptoms may take more than 1 year, but it is not known to what extent the pandemic may influence recovery time and further research is needed.

It is known that postnatal depression has long-term consequences for both mother and infant, so identifying the risk factors involved could help to conduct targeted screening as well as to design targeted intervention strategies to prevent the long-term impact of the pandemic on maternal mental health and infant development[

18,

19].

In terms of mothers' background, 69.5% (598) were from urban areas and 30.5% (262) from rural areas. The implemented preventive measures, quarantine, home isolation, social distancing, aimed at stopping further spread of the virus, have increased the level of anxiety and stress among postpartum women [

20,

21], especially for mothers living in urban areas [

22], regarded as high incidence areas[

23].

The occurrence of postpartum depressive disorder is significantly influenced by the type of birth. Of the 860 patients included in the study, 57.7% (496) gave birth by caesarean section and 42.3% (364) gave birth naturally. In terms of the mother's wishes regarding the type of birth, 71.9% (618) would have preferred a natural birth and 28.1% (242) would have opted for a caesarean birth. The obstetrician also considers the mother's wishes when deciding on the type of birth. The proportion of births by caesarean section, for mothers who wanted caesarean section, was significantly increased compared to the proportion of caesarean sections for mothers who wanted to give birth naturally during the period of our study.

Mothers who gave birth during the pandemic reported a higher level of perceived pain during labor [

24] or during the recovery period secondary to caesarean section. A significant association between type of birth and depressive disorder was established in our own study, the proportion of mothers without depressive disorder was significantly increased among those who gave birth naturally while the proportion of mothers with major depressive disorder was significantly decreased for mothers who gave birth naturally. In addition, patients who gave birth by caesarean section or those who experienced perinatal complications [

25]tend to be more depressed as the length of hospital stay increases [

26]. It is important to mention that the presence of cardiovascular risk factors with a negative impact on pregnancy can also affect the mother’s physical well-being, therefore, it is crucial to identify and properly treat these factors for optimal maternal health[

27]. These aspects seem to be responsible for the increased risk of postpartum depression.

In contrast to the findings in most previous studies, single mothers did not show symptoms of postpartum depression to a significantly greater extent than mothers who were married or cohabiting. By marital status, 86.7% (746) of the mothers included in the study were married, 11.4% (98) were cohabiting and 1.9% (16) were single. Paternal support is known to play an important role in the postnatal period, but was not interpreted during this study.

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased women's insecurity from many perspectives. The present study also investigated the risk of postnatal depression according to mothers' background, education level, socio-economic conditions, and these variables were found to have a greater impact on depressive symptoms compared to younger age or unmarried status. Women with a good standard of living appear to have a lower risk of experiencing postnatal depression. Research conducted between 2020 and 2021 highlighted an increased prevalence of food insecurity due to negative changes in food availability [

28]. Lack of food security negatively influences quality of life and thus health status, and is associated with poor nutrition for pregnant or breastfeeding women, obesity, depression and even high mortality rates[

29].Post-partum depression, when associated with the food insecurity found among families with poor living conditions, increases the risk of delayed early child development[

30]. Families with poor living conditions should therefore be identified and supported to prevent maternal mental health problems.

The study showed that postpartum depression was influenced by parity. 65.2% of the patients were primiparous. Multiparous mothers are less likely to experience postpartum depression compared to primiparous mothers. According to a study in peer reviewed literature, 50-60% of women experience postpartum depression after their first birth[

31].Also, a study conducted in Japan identified a positive correlation between perinatal depressive disorder and primiparity [

32]. The experience of the first child may cause more fear and anxiety about childbirth or the immediate postpartum period, therefore, the support of these women could contribute to the prevention and timely diagnosis of depressive disorder with onset close to parturition.

The conducted research supports existing studies on the prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic [

33,

34,

35].

These findings indicated that the pandemic caused by the spread of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19), as an acute public health problem, requires ongoing, comprehensive and long-term health education to effectively mitigate panic and fear in women, thereby improving the ability of such a vulnerable population to respond in the future in a similar context.

Research on postnatal depression is challenging due to the complexity of the factors involved, therefore some limitations of the study should also be considered. Firstly, the questionnaire was also completed online via the Google Forms application and promoted via social media, a sampling technique that carries an inherent risk in terms of meeting the selection criteria of the study population. However, online surveys are also considered a good method of population recruitment for epidemiological research, especially in pandemic settings, and internet use is high among women of childbearing age in Europe [

36,

37]. Compared to national birth data, enrolled participants were predominantly primiparous, highly educated, married, from urban areas, with a good standard of living, and without a significant personal pathological history. Given that women with higher education and the support of a partner tend to experience fewer symptoms of postpartum depression [

38,

39], while those with a lower level of education were susceptible for the appearance of postnatal suicide ideation[

40], the high prevalence observed in our sample could shed light on the impact of the pandemic. It is also possible that mothers with marked anxiety and more severe symptoms of postnatal depressive disorder may not have completed the online questionnaire, and the likelihood of their being caught in the course of those approached during hospitalization is uncertain. Therefore, the high prevalence of postnatal depressive disorder observed in the study population may still reflect an underestimation of the pandemic situation in the general population. Second, the lack of a comparison group as well as the cross-sectional study design prevented us from drawing conclusions about the long-term consequences of the pandemic (whether the mental distress noted would subside in the short term or persist for a longer period of time). Such research requires longitudinal studies, conducted over several years, which are therefore more costly and time-consuming, but which demonstrate the validity of the results. Third, recruiting patients in the postnatal period of pandemic times has been challenging because of the vulnerable terrain faced by new mothers, requiring extra involvement, patience, empathy and extra attention from researchers. Ultimately, regression models only observed associations between socio-demographic conditions, health status and a few obstetric features of the patients.

Future studies should aim to examine what other variables may influence women's psychological well-being, including the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Postpartum depressive disorder is known to have multifactorial causes, with the substrate being generated by a combination of factors: biological, psychological, social. Biological factors (hormonal changes, genetic predisposition or neurochemical imbalances) interact with psychosocial factors (stress, lack of family support, traumatic life events), this multifactorial nature makes it difficult to isolate specific causes or determine the relative contributions of each factor.

Despite these difficulties, research efforts are aimed at improving the understanding of postpartum depressive disorder, the accuracy and precision of diagnosis, and the development of effective interventions to reduce the stigma associated with the condition

5. Conclusions

Women who gave birth during the COVID-19 pandemic are part of a susceptible, high-risk group that should be closely monitored to minimise the effects of possible undiagnosed postnatal depressive disorder. As noted, the onset of the pandemic has generated major changes in postpartum care and created new challenges that could negatively impact maternal mental health. The effects of the pandemic on mental health are of particular concern for women in the first year after childbirth. Observing these challenges and developing effective measures to prepare our health system early can be of great help for similar situations in the future. This will help and facilitate effective mental health screening for postpartum women, promoting maternal and child health. Therefore, more research is needed to understand the relationship between COVID-19 and postnatal depressive disorder.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C. and M.L.C.; methodology, L.C. and E.S.B.; software, A.T.; validation, A.T., V.R.E. and R.N.; formal analysis, L.H., B.C.B., L.B.; investigation, M.O.T., C.O.N.; resources, A.L.M. and L.B.; data curation, L.C., M.O.T.; writing—original draft preparation, L.C. and C.O.N.; writing—review and editing, L.C.,V.R.E. and E.S.B.; visualization, R.N. and B.C.B.; supervision, M.L.C. and E.S.B.; project administration, M.L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Local Commission of Ethics for Scientific Research from the Timis County Emergency Clinical Hospital “Pius Brinzeu” from Timisoara, Romania operates under article 167 provisions of Law no. 95/2006, art. 28, chapter VIII of order 904/2006 and with EU GCP Directives 2005/28/EC, International Conference of Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH), and with the Declaration of Helsinki— Recommendations Guiding Medical Doctors in Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects. The curent study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, followed the European Union General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) andwas approved by the The Local Commission of Ethics for Scientific Research from the Timis County Emergency Clinical Hospital “Pius Brinzeu” from Timisoara, Romania, No. 184/10.02.2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Borges do Nascimento, I.J.; Cacic, N.; Abdulazeem, H.M.; von Groote, T.C.; Jayarajah, U.; Weerasekara, I.; Esfahani, M.A.; Civile, V.T.; Marusic, A.; Jeroncic, A.; et al. Novel Coronavirus Infection (COVID-19) in Humans: A Scoping Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2020, 9, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceulemans, M.; Foulon, V.; Ngo, E.; Panchaud, A.; Winterfeld, U.; Pomar, L.; Lambelet, V.; Cleary, B.; O’Shaughnessy, F.; Passier, A.; et al. Mental Health Status of Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women during the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Multinational Cross-sectional Study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2021, 100, 1219–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thapa, S.B.; Mainali, A.; Schwank, S.E.; Acharya, G. Maternal Mental Health in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2020, 99, 817–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, M.; Hope, H.; Ford, T.; Hatch, S.; Hotopf, M.; John, A.; Kontopantelis, E.; Webb, R.; Wessely, S.; McManus, S.; et al. Mental Health before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Probability Sample Survey of the UK Population. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maternal Mental Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use/promotion-prevention/maternal-mental-health (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Allotey, J.; Stallings, E.; Bonet, M.; Yap, M.; Chatterjee, S.; Kew, T.; Debenham, L.; Llavall, A.C.; Dixit, A.; Zhou, D.; et al. Clinical Manifestations, Risk Factors, and Maternal and Perinatal Outcomes of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Pregnancy: Living Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ 2020, 370, m3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westgren, M.; Pettersson, K.; Hagberg, H.; Acharya, G. Severe Maternal Morbidity and Mortality Associated with COVID-19: The Risk Should Not Be Downplayed. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2020, 99, 815–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, E.; Senger, C.A.; Henninger, M.; Gaynes, B.N.; Coppola, E.; Soulsby Weyrich, M. Interventions to Prevent Perinatal Depression: A Systematic Evidence Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses, formerly Systematic Evidence Reviews; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville (MD), 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Liang, H.-F.; Chen, J.; Li, Z.-B.; Han, Y.-S.; Chen, J.-X.; Li, J.-C. Postpartum Depression: Current Status and Possible Identification Using Biomarkers. Front Psychiatry 2021, 12, 620371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, M.H.; Meyer, S.; Meah, V.L.; Strynadka, M.C.; Khurana, R. Moms Are Not OK: COVID-19 and Maternal Mental Health. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceulemans, M.; Hompes, T.; Foulon, V. Mental Health Status of Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Call for Action. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2020, 151, 146–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.L.; Holden, J.M.; Sagovsky, R. Detection of Postnatal Depression. Development of the 10-Item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987, 150, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebel, C.; MacKinnon, A.; Bagshawe, M.; Tomfohr-Madsen, L.; Giesbrecht, G. Elevated Depression and Anxiety Symptoms among Pregnant Individuals during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Affect Disord 2020, 277, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levis, B.; Negeri, Z.; Sun, Y.; Benedetti, A.; Thombs, B.D. ; DEPRESsion Screening Data (DEPRESSD) EPDS Group Accuracy of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) for Screening to Detect Major Depression among Pregnant and Postpartum Women: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Individual Participant Data. BMJ 2020, 371, m4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadi, A.F.; Miller, E.R.; Mwanri, L. Postnatal Depression and Its Association with Adverse Infant Health Outcomes in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2020, 20, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Cross, W.M.; Plummer, V.; Lam, L.; Tang, S. A Systematic Review of Prevalence and Risk Factors of Postpartum Depression in Chinese Immigrant Women. Women Birth 2019, 32, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.; Ding, Y.; Guo, W. Mental Health of Pregnant and Postpartum Women During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Psychol 2020, 11, 617001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan Mohamed Radzi, C.W.J.B.; Salarzadeh Jenatabadi, H.; Samsudin, N. Postpartum Depression Symptoms in Survey-Based Research: A Structural Equation Analysis. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, E.E.; Joyce, K.M.; Delaquis, C.P.; Reynolds, K.; Protudjer, J.L.P.; Roos, L.E. Maternal Psychological Distress & Mental Health Service Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Affect Disord 2020, 276, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanov, J.; Stankovic, M.; Zikic, O.; Stankovic, M.; Stojanov, A. The Risk for Nonpsychotic Postpartum Mood and Anxiety Disorders during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Psychiatry Med 2021, 56, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanardo, V.; Manghina, V.; Giliberti, L.; Vettore, M.; Severino, L.; Straface, G. Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Quarantine Measures in Northeastern Italy on Mothers in the Immediate Postpartum Period. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2020, 150, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, J.; Leszczak, J.; Baran, R.; Biesiadecka, A.; Weres, A.; Czenczek-Lewandowska, E.; Kalandyk-Osinko, K. Prenatal and Postnatal Anxiety and Depression in Mothers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Clin Med 2021, 10, 3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushima, M.; Tsuno, K.; Okawa, S.; Hori, A.; Tabuchi, T. Trust and Well-Being of Postpartum Women during the COVID-19 Crisis: Depression and Fear of COVID-19. SSM Popul Health 2021, 15, 100903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariño-Narvaez, C.; Puertas-Gonzalez, J.A.; Romero-Gonzalez, B.; Peralta-Ramirez, M.I. Giving Birth during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Impact on Birth Satisfaction and Postpartum Depression. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2021, 153, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, M.; Agarwal, N.; Agrawal, A.G. Impact of COVID-19 Institutional Isolation Measures on Postnatal Women in Level 3 COVID Facility in Northern India. Journal of South Asian Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2021, 13, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Dhillon, P. Length of Stay after Childbirth in India: A Comparative Study of Public and Private Health Institutions. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2020, 20, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Awwad, S.-A.; Craina, M.; Gluhovschi, A.; Boscu, L.; Bernad, E.; Iurciuc, M.; Abu-Awwad, A.; Iurciuc, S.; Tudoran, C.; Bernad, R.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Neonatal Effects in Pregnant Women with Cardiovascular Risk versus Low-Risk Pregnant Women. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12, 4082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louie, S.; Shi, Y.; Allman-Farinelli, M. The Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Food Security in Australia: A Scoping Review. Nutr Diet 2022, 79, 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, R.; Giskes, K.; Turrell, G.; Gallegos, D. Food Insecurity among Adults Residing in Disadvantaged Urban Areas: Potential Health and Dietary Consequences. Public Health Nutr 2012, 15, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroso, J.; Buccini, G.; Venancio, S.I.; Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Gubert, M.B. Maternal Mental Health Modifies the Association of Food Insecurity and Early Child Development. Matern Child Nutr 2020, 16, e12997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dira, I.K.P.A.; Wahyuni, A.A.S. PREVALENSI DAN FAKTOR RISIKO DEPRESI POSTPARTUM DI KOTA DENPASAR MENGGUNAKAN EDINBURGH POSTNATAL DEPRESSION SCALE. E-Jurnal Medika Udayana 2016, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Tamaki, R.; Murata, M.; Okano, T. Risk Factors for Postpartum Depression in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1997, 51, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Shuai, H.; Cai, Z.; Fu, X.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, W.; Krabbendam, E.; Liu, S.; et al. Mapping Global Prevalence of Depression among Postpartum Women. Transl Psychiatry 2021, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, H.; Duan, C.; Li, C.; Fan, J.; Li, H.; Chen, L.; Xu, H.; Li, X.; et al. Perinatal Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms of Pregnant Women during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Outbreak in China. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020, 223, 240.e1–240.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galletta, M.A.K.; Oliveira, A.M. da S.S.; Albertini, J.G.L.; Benute, G.G.; Peres, S.V.; Brizot, M. de L.; Francisco, R.P.V.; HC-FMUSP-Obstetric COVID19 Study Group Postpartum Depressive Symptoms of Brazilian Women during the COVID-19 Pandemic Measured by the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. J Affect Disord 2022, 296, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Gelder, M.M.H.J.; Bretveld, R.W.; Roeleveld, N. Web-Based Questionnaires: The Future in Epidemiology? Am J Epidemiol 2010, 172, 1292–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics | Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/isoc_r_broad_h/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Biaggi, A.; Conroy, S.; Pawlby, S.; Pariante, C.M. Identifying the Women at Risk of Antenatal Anxiety and Depression: A Systematic Review. J Affect Disord 2016, 191, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumura, K.; Hamazaki, K.; Tsuchida, A.; Kasamatsu, H.; Inadera, H. ; Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS) Group Education Level and Risk of Postpartum Depression: Results from the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS). BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enătescu, I.; Craina, M.; Gluhovschi, A.; Giurgi-Oncu, C.; Hogea, L.; Nussbaum, L.A.; Bernad, E.; Simu, M.; Cosman, D.; Iacob, D.; et al. The Role of Personality Dimensions and Trait Anxiety in Increasing the Likelihood of Suicide Ideation in Women during the Perinatal Period. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology 2021, 42, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).