Submitted:

22 September 2023

Posted:

25 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Clinical features of BC

2.1. Risk factors of BC

2.2. BC diagnosis

2.3. BC staging, grading and classification

- Ductal Carcinoma in situ (DCIS). This is a very early form of cancer that has not spread. DCIS is a type of early BC inside of the ductal system that has not attacked the nearby tissue. It is one of the common types of non-invasive cancer.

- Infiltrating or invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), i.e. the most widespread kind of BC. It begins in the milk ducts and can spread to surrounding tissues and eventually to other parts of the body.

- Medullary carcinoma. It constitutes roughly 15% of all BCs. Middle aged women are more likely to be affected. Cellular histology shows a resemblance to the brain medulla (gray matter).

- Lobular Carcinoma in situ (LCIS), recently renamed “lobular neoplasia”, i.e. a non-invasive and less common form of tumor. It is unlikely to turn into invasive cancer. LCIS is considered more akin to a “marker” that BC may develop.

- Infiltrating Lobular Carcinoma (ILC), i.e. the second most common type of BC after invasive ductal carcinoma. The cancer starts in the lobules or lobes and then spreads. Initial apparent thickening in the upper-outer section of the breast is usually reported. Such carcinomas are usually positive for estrogen and progesterone receptors, and therefore hormone therapy can be a valid therapeutic option.

- Tubular carcinoma. The cancer cells come to resemble tiny tubules. Women aged 50 and older are typically affected. Adjuvant systemic therapy is an effective therapeutic option.

- Mucinous carcinoma or colloid. It is a somewhat rare and invasive BC that seldom spreads to the lymph nodes. The cancer cells are known to produce mucus. Jelly-like tumors result from the combination of mucous and cancer cells.

- Paget’s disease. This leads to an eczema-like change in the skin of the nipple. Itchiness, scaling and oozing discharge from the nipple have been reported. An underlying BC is reported in 90% of patients with such symptoms have. Women in their 50s are most likely to be affected, although Paget’s disease can happen at any age.

- Inflammatory breast cancer, i.e. a rare, yet rather aggressive type of BC, which can cause the blockage of the lymph vessels in breast skin. The cancer manifests itself over a rather large area blanketing the breast, rather than a lump, and causes swelling and inflammation.

- Triple negative breast cancer. Such an BC type is known to be negative for estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and HER2/neu proteins. The acronym HER stands for “human epidermal growth factor receptor”)

- Metastatic breast cancer, i.e. a later BC stage which has metastasized to other organs (typically liver, brain, bones among others) [52].

2.4. BC treatment

- surgery

- radiotherapy

- chemotherapy

- hormone therapy

- targeted therapy

- Immunotherapy.

- Neoadjuvant systemic therapy for non-metastatic BC.

3. Epigenetics of BC and the role of miR-125

3.1. microRNA: biogenesis and classification

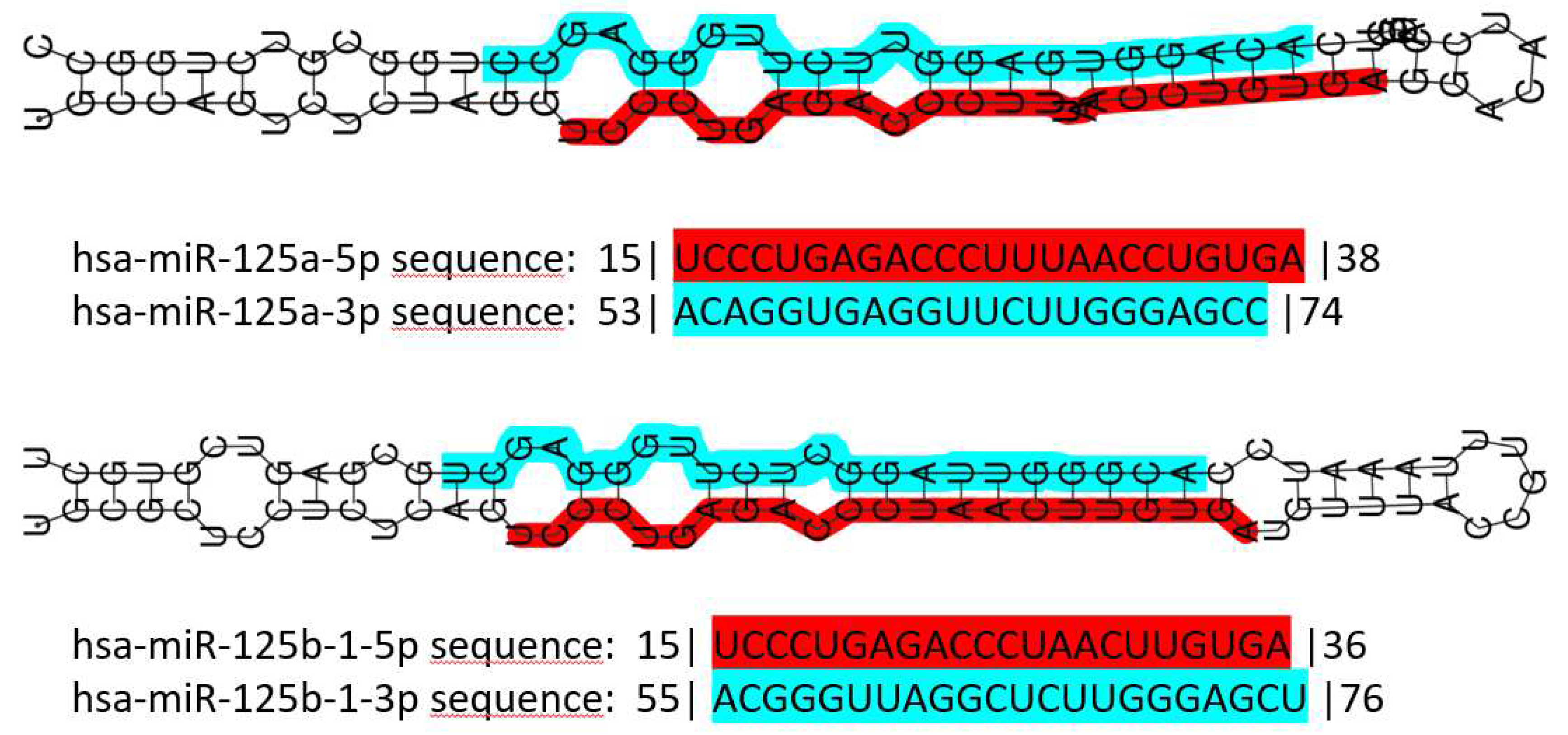

3.2. The miR-125 family: molecular organization and roles in human pathology

3.3. miR-125 and cancer

3.4. Role of miR-125 in BC

3.5. Further mining miR-125 function in BC: competing endogenous RNA networks (ceRNETs).

3.6. Beyond clinical factors: new standards for a legally and ethically tenable implementation of personalized medicine

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Winters, S.; Martin, C.; Murphy, D.; Shokar, N.K. Breast Cancer Epidemiology, Prevention, and Screening. In Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science; 2017; Vol. 151.

- Arnold, M.; Morgan, E.; Rumgay, H.; Mafra, A.; Singh, D.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Gralow, J.R.; Cardoso, F.; Siesling, S.; et al. Current and Future Burden of Breast Cancer: Global Statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast 2022, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSantis, C.E.; Fedewa, S.A.; Goding Sauer, A.; Kramer, J.L.; Smith, R.A.; Jemal, A. Breast Cancer Statistics, 2015: Convergence of Incidence Rates between Black and White Women. CA Cancer J Clin 2016, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R. Global, Regional, National Burden of Breast Cancer in 185 Countries: Evidence from GLOBOCAN 2018. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2021, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coughlin, S.S. Epidemiology of Breast Cancer in Women. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; 2019; Vol. 1152.

- Majeed, W.; Aslam, B.; Javed, I.; Khaliq, T.; Muhammad, F.; Ali, A.; Raza, A. Breast Cancer: Major Risk Factors and Recent Developments in Treatment. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 2014, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galati, F.; Magri, V.; Arias-Cadena, P.A.; Moffa, G.; Rizzo, V.; Pasculli, M.; Botticelli, A.; Pediconi, F. Pregnancy-Associated Breast Cancer: A Diagnostic and Therapeutic Challenge. Diagnostics 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Key, T. Sex Hormones and Risk of Breast Cancer in Premenopausal Women: A Collaborative Reanalysis of Individual Participant Data from Seven Prospective Studies. Lancet Oncol 2013, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Wang, M.; Anderson, K.; Baglietto, L.; Bergkvist, L.; Bernstein, L.; van den Brandt, P.A.; Brinton, L.; Buring, J.E.; Heather Eliassen, A.; et al. Alcohol Consumption and Breast Cancer Risk by Estrogen Receptor Status: In a Pooled Analysis of 20 Studies. Int J Epidemiol 2016, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodewes, F.T.H.; van Asselt, A.A.; Dorrius, M.D.; Greuter, M.J.W.; de Bock, G.H. Mammographic Breast Density and the Risk of Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Breast 2022, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampaolino, P.; Cafasso, V.; Boccia, D.; Ascione, M.; Mercorio, A.; Viciglione, F.; Palumbo, M.; Serafino, P.; Buonfantino, C.; De Angelis, M.C.; et al. Fertility-Sparing Approach in Patients with Endometrioid Endometrial Cancer Grade 2 Stage IA (FIGO): A Qualitative Systematic Review. Biomed Res Int 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu, L.; Manavella, D.D.; Gullo, G.; McNamara, B.; Santin, A.D.; Patrizio, P. Endometrial Cancer in Reproductive Age: Fertility-Sparing Approach and Reproductive Outcomes. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullo, G.; Cucinella, G.; Chiantera, V.; Dellino, M.; Cascardi, E.; Török, P.; Herman, T.; Garzon, S.; Uccella, S.; Laganà, A.S. Fertility-Sparing Strategies for Early-Stage Endometrial Cancer: Stepping towards Precision Medicine Based on the Molecular Fingerprint. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piergentili, R.; Gullo, G.; Basile, G.; Gulia, C.; Porrello, A.; Cucinella, G.; Marinelli, E.; Zaami, S. Circulating MiRNAs as a Tool for Early Diagnosis of Endometrial Cancer—Implications for the Fertility-Sparing Process: Clinical, Biological, and Legal Aspects. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 11356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gullo, G.; Perino, A.; Cucinella, G. Open vs. Closed Vitrification System: Which One Is Safer? Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2022, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Zaami, S.; Stark, M.; Signore, F.; Gullo, G.; Marinelli, E. Fertility Preservation in Female Cancer Sufferers: (Only) a Moral Obligation? European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knabben, L.; Mueller, M.D. Breast Cancer and Pregnancy. In Proceedings of the Hormone Molecular Biology and Clinical Investigation; 2017; Vol. 32.

- Burgio, S.; Polizzi, C.; Buzzaccarini, G.; Laganà, A.S.; Gullo, G.; Perricone, G.; Perino, A.; Cucinella, G.; Alesi, M. Psychological Variables in Medically Assisted Reproduction: A Systematic Review. Przeglad Menopauzalny 2022, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smrekar, K.; Lodise, N.M. Combined Oral Contraceptive Use and Breast Cancer Risk: Select Considerations for Clinicians. Nurs Womens Health 2022, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamani, M.O.; Akgor, U.; Gültekin, M. Review of the Literature on Combined Oral Contraceptives and Cancer. Ecancermedicalscience 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrucelli, N.; Daly, M.B.; Pal, T. BRCA1- and BRCA2-Associated Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer; 1993.

- Carbognin, L.; Miglietta, F.; Paris, I.; Dieci, M.V. Prognostic and Predictive Implications of PTEN in Breast Cancer: Unfulfilled Promises but Intriguing Perspectives. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbandi, A.; Nguyen, H.D.; Jackson, J.G. TP53 Mutations and Outcomes in Breast Cancer: Reading beyond the Headlines. Trends Cancer 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, G.; Veronesi, P.; Sacchini, V.; Galimberti, V. Prognosis and Outcome in CDH1-Mutant Lobular Breast Cancer. European Journal of Cancer Prevention 2018, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beggs, A.D.; Latchford, A.R.; Vasen, H.F.A.; Moslein, G.; Alonso, A.; Aretz, S.; Bertario, L.; Blanco, I.; Bülow, S.; Burn, J.; et al. Peutz - Jeghers Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Recommendations for Management. Gut 2010, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apostolou, P.; Papasotiriou, I. Current Perspectives on CHEK2 Mutations in Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer : Targets and Therapy 2017, 9, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nepomuceno, T.C.; Carvalho, M.A.; Rodrigue, A.; Simard, J.; Masson, J.Y.; Monteiro, A.N.A. PALB2 Variants: Protein Domains and Cancer Susceptibility. Trends Cancer 2021, 7, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stucci, L.S.; Internò, V.; Tucci, M.; Perrone, M.; Mannavola, F.; Palmirotta, R.; Porta, C. The ATM Gene in Breast Cancer: Its Relevance in Clinical Practice. Genes (Basel) 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; McInerny, S.; Zethoven, M.; Cheasley, D.; Lim, B.W.X.; Rowley, S.M.; Devereux, L.; Grewal, N.; Ahmadloo, S.; Byrne, D.; et al. Combined Tumor Sequencing and Case-Control Analyses of RAD51C in Breast Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2019, 111, 1332–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Ouyang, T.; Li, J.; Wang, T.; Fan, Z.; Fan, T.; Lin, B.; Xie, Y. Associations between RAD51D Germline Mutations and Breast Cancer Risk and Survival in BRCA1/2-Negative Breast Cancers. Annals of Oncology 2018, 29, 2046–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Śniadecki, M.; Brzeziński, M.; Darecka, K.; Klasa-Mazurkiewicz, D.; Poniewierza, P.; Krzeszowiec, M.; Kmieć, N.; Wydra, D. BARD1 and Breast Cancer: The Possibility of Creating Screening Tests and New Preventive and Therapeutic Pathways for Predisposed Women. Genes (Basel) 2020, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suarez-Kelly, L.P.; Yu, L.; Kline, D.; Schneider, E.B.; Agnese, D.M.; Carson, W.E. Increased Breast Cancer Risk in Women with Neurofibromatosis Type 1: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of the Literature. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 2019, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, U.; Khan, M.S. Prognostic Value Estimation of BRIP1 in Breast Cancer by Exploiting Transcriptomics Data Through Bioinformatics Approaches. Bioinform Biol Insights 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Beeghly-Fadiel, A.; Long, J.; Zheng, W. Genetic Variants Associated with Breast-Cancer Risk: Comprehensive Research Synopsis, Meta-Analysis, and Epidemiological Evidence. Lancet Oncol 2011, 12, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niell, B.L.; Freer, P.E.; Weinfurtner, R.J.; Arleo, E.K.; Drukteinis, J.S. Screening for Breast Cancer. Radiol Clin North Am 2017, 55, 1145–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreea, G.I.; Pegza, R.; Lascu, L.; Bondari, S.; Stoica, Z.; Bondari, A. The Role of Imaging Techniques in Diagnosis of Breast Cancer. 2012.

- Albert, U.S.; Altland, H.; Duda, V.; Engel, J.; Geraedts, M.; Heywang-Köbrunner, S.; Hölzel, D.; Kalbheim, E.; Koller, M.; König, K.; et al. 2008 Update of the Guideline: Early Detection of Breast Cancer in Germany. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2009, 135, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, Z.S.; Ebadi, M.R.; Amjad, G.; Younesi, L. Application of Imaging Technologies in Breast Cancer Detection: A Review Article. Open Access Maced J Med Sci 2019, 7, 838–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerami, R.; Joni, S.S.; Akhondi, N.; Etemadi, A.; Fosouli, M.; Eghbal, A.F.; Souri, Z. A Literature Review on the Imaging Methods for Breast Cancer. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol 2022, 14, 171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Z.; Amin, A.; Roy, A.; Pulliam, N.E.; Karavites, L.C.; Espino, S.; Helenowski, I.; Li, X.; Luo, Y.; Khan, S.A. Preoperative Magnetic Resonance Imaging Use and Oncologic Outcomes in Premenopausal Breast Cancer Patients. NPJ Breast Cancer 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Bairi, K.; Haynes, H.R.; Blackley, E.; Fineberg, S.; Shear, J.; Turner, S.; de Freitas, J.R.; Sur, D.; Amendola, L.C.; Gharib, M.; et al. The Tale of TILs in Breast Cancer: A Report from The International Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Working Group. NPJ Breast Cancer 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dromain, C.; Balleyguier, C. Contrast-Enhanced Digital Mammography. 2010, 187–198. [CrossRef]

- Mortezazadeh, T.; Gholibegloo, E.; Riyahi, A.N.; Haghgoo, S.; Musa, A.E.; Khoobi, M. Glucosamine Conjugated Gadolinium (III) Oxide Nanoparticles as a Novel Targeted Contrast Agent for Cancer Diagnosis in MRI. J Biomed Phys Eng 2020, 10, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Lu, G.; Qin, B.; Fei, B. Ultrasound Imaging Technologies for Breast Cancer Detection and Management: A Review. Ultrasound Med Biol 2018, 44, 37–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentier, B.; Hayward, J.; Strachowski, L. Enhancing Your Acoustics: Ultrasound Image Optimization of Breast Lesions. J Ultrasound Med 2017, 36, 1479–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drukteinis, J.S.; Mooney, B.P.; Flowers, C.I.; Gatenby, R.A. Beyond Mammography: New Frontiers in Breast Cancer Screening. Am J Med 2013, 126, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranmakani, S.; Mortezazadeh, T.; Sajadian, F.; Ghaziani, M.F.; Ghafari, A.; Khezerloo, D.; Musa, A.E. A Review of Various Modalities in Breast Imaging: Technical Aspects and Clinical Outcomes. Egyptian Journal of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine 2020, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronesi, U.; Viale, G.; Rotmensz, N.; Goldhirsch, A. Rethinking TNM: Breast Cancer TNM Classification for Treatment Decision-Making and Research. Breast 2006, 15, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliyatkin, N.; Yalcin, E.; Zengel, B.; Aktaş, S.; Vardar, E. Molecular Classification of Breast Carcinoma: From Traditional, Old-Fashioned Way to A New Age, and A New Way. J Breast Health 2015, 11, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perou, C.M.; Sørile, T.; Eisen, M.B.; Van De Rijn, M.; Jeffrey, S.S.; Ress, C.A.; Pollack, J.R.; Ross, D.T.; Johnsen, H.; Akslen, L.A.; et al. Molecular Portraits of Human Breast Tumours. Nature 2000, 406, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinn, H.P.; Kreipe, H. A Brief Overview of the WHO Classification of Breast Tumors, 4th Edition, Focusing on Issues and Updates from the 3rd Edition. Breast Care (Basel) 2013, 8, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hortobagyi, G.N.; Edge, S.B.; Giuliano, A. New and Important Changes in the TNM Staging System for Breast Cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2018, 38, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuliano, A.E.; Connolly, J.L.; Edge, S.B.; Mittendorf, E.A.; Rugo, H.S.; Solin, L.J.; Weaver, D.L.; Winchester, D.J.; Hortobagyi, G.N. Breast Cancer-Major Changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer Eighth Edition Cancer Staging Manual. CA Cancer J Clin 2017, 67, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisusi, F.A.; Akala, E.O. Drug Combinations in Breast Cancer Therapy. Pharm Nanotechnol 2019, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstein, H.J.; Curigliano, G.; Thürlimann, B.; Weber, W.P.; Poortmans, P.; Regan, M.M.; Senn, H.J.; Winer, E.P.; Gnant, M.; Aebi, S.; et al. Customizing Local and Systemic Therapies for Women with Early Breast Cancer: The St. Gallen International Consensus Guidelines for Treatment of Early Breast Cancer 2021. Ann Oncol 2021, 32, 1216–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Iwamoto, M.; Kimura, K.; Matsunami, N.; Morishima, H.; Yoshidome, K.; Nomura, T.; Morimoto, T.; Yamamoto, D.; Tsubota, Y.; et al. Phase II Study of Neoadjuvant Anthracycline-Based Regimens Combined With Nanoparticle Albumin-Bound Paclitaxel and Trastuzumab for Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Positive Operable Breast Cancer. Clin Breast Cancer 2015, 15, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, S.; McGale, P.; Correa, C.; Taylor, C.; Arriagada, R.; Clarke, M.; Cutter, D.; Davies, C.; Ewertz, M.; Godwin, J.; et al. Effect of Radiotherapy after Breast-Conserving Surgery on 10-Year Recurrence and 15-Year Breast Cancer Death: Meta-Analysis of Individual Patient Data for 10,801 Women in 17 Randomised Trials. Lancet 2011, 378, 1707–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayan, M.; Yehia, Z.A.; Ohri, N.; Haffty, B.G. Hypofractionated Postmastectomy Radiation Therapy. Adv Radiat Oncol 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschini, G.; Sanchez, A.M.; Di Leone, A.; Magno, S.; Moschella, F.; Accetta, C.; Masetti, R. New Trends in Breast Cancer Surgery: A Therapeutic Approach Increasingly Efficacy and Respectful of the Patient. G Chir 2015, 36, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tung, N.; Garber, J.E. PARP Inhibition in Breast Cancer: Progress Made and Future Hopes. NPJ Breast Cancer 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues-Ferreira, S.; Nahmias, C. Predictive Biomarkers for Personalized Medicine in Breast Cancer. Cancer Lett 2022, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeli, P.; Winter, T.; Hackett, A.P.; Alboushi, L.; Jafarnejad, S.M. The Intricate Balance between MicroRNA-Induced MRNA Decay and Translational Repression. FEBS J 2023, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, R.C.; Farh, K.K.H.; Burge, C.B.; Bartel, D.P. Most Mammalian MRNAs Are Conserved Targets of MicroRNAs. Genome Res 2009, 19, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A.; Griffiths-Jones, S.; Ashurst, J.L.; Bradley, A. Identification of Mammalian MicroRNA Host Genes and Transcription Units. Genome Res 2004, 14, 1902–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piergentili, R.; Basile, G.; Nocella, C.; Carnevale, R.; Marinelli, E.; Patrone, R.; Zaami, S. Using NcRNAs as Tools in Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment—The Way towards Personalized Medicine to Improve Patients’ Health. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.; Hayder, H.; Zayed, Y.; Peng, C. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018, 9, 388354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, M.; Han, J.; Yeom, K.H.; Lee, S.; Baek, S.H.; Kim, V.N. MicroRNA Genes Are Transcribed by RNA Polymerase II. EMBO J 2004, 23, 4051–4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijer, H.A.; Smith, E.M.; Bushell, M. Regulation of MiRNA Strand Selection: Follow the Leader? Biochem Soc Trans 2014, 42, 1135–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambros, V.; Bartel, B.; Bartel, D.P.; Burge, C.B.; Carrington, J.C.; Chen, X.; Dreyfuss, G.; Eddy, S.R.; Griffiths-Jones, S.; Marshall, M.; et al. A Uniform System for MicroRNA Annotation. RNA 2003, 9, 277–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths-Jones, S.; Grocock, R.J.; van Dongen, S.; Bateman, A.; Enright, A.J. MiRBase: MicroRNA Sequences, Targets and Gene Nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res 2006, 34, D140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.C.; Feinbaum, R.L.; Ambros, V. The C. Elegans Heterochronic Gene Lin-4 Encodes Small RNAs with Antisense Complementarity to Lin-14. Cell 1993, 75, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, R.; Pak, C.H.; Jin, P. Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Associated with Mature MiR-125a Alters the Processing of Pri-MiRNA. Hum Mol Genet 2007, 16, 1124–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaham, L.; Binder, V.; Gefen, N.; Borkhardt, A.; Izraeli, S. MiR-125 in Normal and Malignant Hematopoiesis. Leukemia 2012 26:9 2012, 26, 2011–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciafrè, S.A.; Galardi, S.; Mangiola, A.; Ferracin, M.; Liu, C.G.; Sabatino, G.; Negrini, M.; Maira, G.; Croce, C.M.; Farace, M.G. Extensive Modulation of a Set of MicroRNAs in Primary Glioblastoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005, 334, 1351–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmrich, S.; Streltsov, A.; Schmidt, F.; Thangapandi, V.R.; Reinhardt, D.; Klusmann, J.H. LincRNAs MONC and MIR100HG Act as Oncogenes in Acute Megakaryoblastic Leukemia. Mol Cancer 2014, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagos-Quintana, M.; Rauhut, R.; Yalcin, A.; Meyer, J.; Lendeckel, W.; Tuschl, T. Identification of Tissue-Specific MicroRNAs from Mouse. Curr Biol 2002, 12, 735–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.Y.; Lin, Y.C.D.; Cui, S.; Huang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xu, J.; Bao, J.; Li, Y.; Wen, J.; Zuo, H.; et al. MiRTarBase Update 2022: An Informative Resource for Experimentally Validated MiRNA-Target Interactions. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, D222–D230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MiRTarBase: The Experimentally Validated MicroRNA-Target Interactions Database Available online:. Available online: https://mirtarbase.cuhk.edu.cn/~miRTarBase/miRTarBase_2022/php/index.php (accessed on 24 August 2023).

- Sun, Y.M.; Lin, K.Y.; Chen, Y.Q. Diverse Functions of MiR-125 Family in Different Cell Contexts. J Hematol Oncol 2013, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Y.; Sun, Y.; Chen, J. IGF-II Is Regulated by MicroRNA-125b in Skeletal Myogenesis. J Cell Biol 2011, 192, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, R.; Liang, W.; Ma, W.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, Z.; Ding, F.; Sun, H. MiR-125b-5p Targeting TRAF6 Relieves Skeletal Muscle Atrophy Induced by Fasting or Denervation. Ann Transl Med 2019, 7, 456–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; He, L.; Li, X.; Pei, W.; Yang, H.; Zhong, M.; Zhang, M.; Lv, K.; Zhang, Y. LncRNA AK089514/MiR-125b-5p/TRAF6 Axis Mediates Macrophage Polarization in Allergic Asthma. BMC Pulm Med 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ha, T.; Zou, J.; Ren, D.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Kalbfleisch, J.; Gao, X.; Williams, D.; Li, C. MicroRNA-125b Protects against Myocardial Ischaemia/Reperfusion Injury via Targeting P53-Mediated Apoptotic Signalling and TRAF6. Cardiovasc Res 2014, 102, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medrano, S.; Monteagudo, M.C.; Sequeira-Lopez, M.L.S.; Pentz, E.S.; Ariel Gomez, R. Two MicroRNAs, MiR-330 and MiR-125b-5p, Mark the Juxtaglomerular Cell and Balance Its Smooth Muscle Phenotype. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2012, 302, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Gao, Y.; Yu, C.; Nie, Z.; Lu, R.; Sun, Y.; Guan, Z. MicroRNA-125b Inhibits the Proliferation of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Induced by Platelet-Derived Growth Factor BB. Exp Ther Med 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Tan, J.; Wang, L.; Pei, G.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, S.; He, C.; Fu, C.; Wei, Q. MiR-125 Family in Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Diseases. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Velasco, E.; Galiano-Torres, J.; Jodar-Garcia, A.; Aranega, A.E.; Franco, D. MiR-27 and MiR-125 Distinctly Regulate Muscle-Enriched Transcription Factors in Cardiac and Skeletal Myocytes. Biomed Res Int 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, Q.; Yuan, Z.; Chen, A.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, H. LncRNA-MALAT1 Promotes CPC Proliferation and Migration in Hypoxia by up-Regulation of JMJD6 via Sponging MiR-125. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018, 499, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Zhang, M.; Chen, W.; Wang, R.; Ye, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Cai, C. LncRNA-HOTAIR Inhibition Aggravates Oxidative Stress-Induced H9c2 Cells Injury through Suppression of MMP2 by MiR-125. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2018, 50, 996–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.Y.; Lee, D.S.; Choong, O.K.; Chang, S.K.; Hsu, T.; Nicholson, M.W.; Liu, L.W.; Lin, P.J.; Ruan, S.C.; Lin, S.W.; et al. Cardiac-Specific MicroRNA-125b Deficiency Induces Perinatal Death and Cardiac Hypertrophy. Sci Rep 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Li, X. NORAD Lentivirus ShRNA Mitigates Fibrosis and Inflammatory Responses in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy via the CeRNA Network of NORAD/MiR-125a-3p/Fyn. Inflamm Res 2021, 70, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sempere, L.F.; Freemantle, S.; Pitha-Rowe, I.; Moss, E.; Dmitrovsky, E.; Ambros, V. Expression Profiling of Mammalian MicroRNAs Uncovers a Subset of Brain-Expressed MicroRNAs with Possible Roles in Murine and Human Neuronal Differentiation. Genome Biol 2004, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, M.T.N.; Xie, H.; Zhou, B.; Chia, P.H.; Rizk, P.; Um, M.; Udolph, G.; Yang, H.; Lim, B.; Lodish, H.F. MicroRNA-125b Promotes Neuronal Differentiation in Human Cells by Repressing Multiple Targets. Mol Cell Biol 2009, 29, 5290–5305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dash, S.; Balasubramaniam, M.; Rana, T.; Godino, A.; Peck, E.G.; Goodwin, J.S.; Villalta, F.; Calipari, E.S.; Nestler, E.J.; Dash, C.; et al. Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase-1 (PARP-1) Induction by Cocaine Is Post-Transcriptionally Regulated by MiR-125b. eNeuro 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edbauer, D.; Neilson, J.R.; Foster, K.A.; Wang, C.F.; Seeburg, D.P.; Batterton, M.N.; Tada, T.; Dolan, B.M.; Sharp, P.A.; Sheng, M. Regulation of Synaptic Structure and Function by FMRP-Associated MicroRNAs MiR-125b and MiR-132. Neuron 2010, 65, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åkerblom, M.; Petri, R.; Sachdeva, R.; Klussendorf, T.; Mattsson, B.; Gentner, B.; Jakobsson, J. MicroRNA-125 Distinguishes Developmentally Generated and Adult-Born Olfactory Bulb Interneurons. Development 2014, 141, 1580–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, U.; Di Carlo, V.; Caramanica, P.; Toselli, C.; Cinquino, A.; Marchioni, M.; Laneve, P.; Biagioni, S.; Bozzoni, I.; Cacci, E.; et al. Mir-23a and Mir-125b Regulate Neural Stem/Progenitor Cell Proliferation by Targeting Musashi1. RNA Biol 2014, 11, 1105–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, A.; Danial, M.; Blelloch, R.H. Let-7 and MiR-125 Cooperate to Prime Progenitors for Astrogliogenesis. EMBO J 2015, 34, 1180–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pogue, A.I.; Cui, J.G.; Li, Y.Y.; Zhao, Y.; Culicchia, F.; Lukiw, W.J. Micro RNA-125b (MiRNA-125b) Function in Astrogliosis and Glial Cell Proliferation. Neurosci Lett 2010, 476, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klusmann, J.H.; Li, Z.; Böhmer, K.; Maroz, A.; Koch, M.L.; Emmrich, S.; Godinho, F.J.; Orkin, S.H.; Reinhardt, D. MiR-125b-2 Is a Potential OncomiR on Human Chromosome 21 in Megakaryoblastic Leukemia. Genes Dev 2010, 24, 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiedt, S.; Prestel, M.; Malik, R.; Schieferdecker, N.; Duering, M.; Kautzky, V.; Stoycheva, I.; Böck, J.; Northoff, B.H.; Klein, M.; et al. RNA-Seq Identifies Circulating MiR-125a-5p, MiR-125b-5p, and MiR-143-3p as Potential Biomarkers for Acute Ischemic Stroke. Circ Res 2017, 121, 970–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Li, L.; Dong, L.; Cheng, J.; Zhao, C.; Bao, C.; Wang, H. Circulating MRNA and MicroRNA Profiling Analysis in Patients with Ischemic Stroke. Mol Med Rep 2020, 22, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banzhaf-Strathmann, J.; Benito, E.; May, S.; Arzberger, T.; Tahirovic, S.; Kretzschmar, H.; Fischer, A.; Edbauer, D. MicroRNA-125b Induces Tau Hyperphosphorylation and Cognitive Deficits in Alzheimer’s Disease. EMBO J 2014, 33, 1667–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandrov, P.N.; Dua, P.; Hill, J.M.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Zhao, Y.; Lukiw, W.J. MicroRNA (MiRNA) Speciation in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) and Extracellular Fluid (ECF). Int J Biochem Mol Biol 2012, 3, 365. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, M.Y.; Cao, X.; Hou, K.C.; Tsai, M.H.; Lee, C.Y.; Kuo, M.F.; Wu, V.C.; Huang, H.Y.; Akbarian, S.; Chang, S.K.; et al. Mir125b-2 Imprinted in Human but Not Mouse Brain Regulates Hippocampal Function and Circuit in Mice. Commun Biol 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Da Silva, A.C.A.L.; Arnold, A.; Okeke, L.; Ames, H.; Correa-Cerro, L.S.; Vizcaino, M.A.; Ho, C.Y.; Eberhart, C.G.; Rodriguez, F.J. MicroRNA (MiR) 125b Regulates Cell Growth and Invasion in Pediatric Low Grade Glioma. Sci Rep 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, E.; De Smaele, E.; Po, A.; Marcotullio, L. Di; Tosi, E.; Espinola, M.S.B.; Rocco, C. Di; Riccardi, R.; Giangaspero, F.; Farcomeni, A.; et al. MicroRNA Profiling in Human Medulloblastoma. Int J Cancer 2009, 124, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laneve, P.; Di Marcotullio, L.; Gioia, U.; Fiori, M.E.; Ferretti, E.; Gulino, A.; Bozzoni, I.; Caffarelli, E. The Interplay between MicroRNAs and the Neurotrophin Receptor Tropomyosin-Related Kinase C Controls Proliferation of Human Neuroblastoma Cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 7957–7962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, N.; Lin, X.; Zhao, X.; Zheng, L.; Xiao, L.; Liu, J.; Ge, L.; Cao, S. MiR-125b Acts as an Oncogene in Glioblastoma Cells and Inhibits Cell Apoptosis through P53 and P38MAPK-Independent Pathways. Br J Cancer 2013, 109, 2853–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, H.F.; He, T.Z.; Liu, C.M.; Cui, Y.; Song, P.P.; Jin, X.H.; Ma, X. MiR-125b Expression Affects the Proliferation and Apoptosis of Human Glioma Cells by Targeting Bmf. Cell Physiol Biochem 2009, 23, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cron, M.A.; Maillard, S.; Delisle, F.; Samson, N.; Truffault, F.; Foti, M.; Fadel, E.; Guihaire, J.; Berrih-Aknin, S.; Le Panse, R. Analysis of MicroRNA Expression in the Thymus of Myasthenia Gravis Patients Opens New Research Avenues. Autoimmun Rev 2018, 17, 588–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojtowicz, E.E.; Lechman, E.R.; Hermans, K.G.; Schoof, E.M.; Wienholds, E.; Isserlin, R.; van Veelen, P.A.; Broekhuis, M.J.C.; Janssen, G.M.C.; Trotman-Grant, A.; et al. Ectopic MiR-125a Expression Induces Long-Term Repopulating Stem Cell Capacity in Mouse and Human Hematopoietic Progenitors. Cell Stem Cell 2016, 19, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Lu, J.; Schlanger, R.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.Y.; Fox, M.C.; Purton, L.E.; Fleming, H.H.; Cobb, B.; Merkenschlager, M.; et al. MicroRNA MiR-125a Controls Hematopoietic Stem Cell Number. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 14229–14234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmrich, S.; Rasche, M.; Schöning, J.; Reimer, C.; Keihani, S.; Maroz, A.; Xie, Y.; Li, Z.; Schambach, A.; Reinhardt, D.; et al. MiR-99a/100~125b Tricistrons Regulate Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cell Homeostasis by Shifting the Balance between TGFβ and Wnt Signaling. Genes Dev 2014, 28, 858–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allantaz, F.; Cheng, D.T.; Bergauer, T.; Ravindran, P.; Rossier, M.F.; Ebeling, M.; Badi, L.; Reis, B.; Bitter, H.; D’Asaro, M.; et al. Expression Profiling of Human Immune Cell Subsets Identifies MiRNA-MRNA Regulatory Relationships Correlated with Cell Type Specific Expression. PLoS One 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.A.; So, A.Y.-L.; Sinha, N.; Gibson, W.S.J.; Taganov, K.D.; O’Connell, R.M.; Baltimore, D. MicroRNA-125b Potentiates Macrophage Activation. J Immunol 2011, 187, 5062–5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhong, M.; Suo, Q.; Lv, K. Expression Profiles of MiRNAs in Polarized Macrophages. Int J Mol Med 2013, 31, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staedel, C.; Darfeuille, F. MicroRNAs and Bacterial Infection. Cell Microbiol 2013, 15, 1496–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, M.; Khoshbakht, T.; Hussen, B.M.; Abdullah, S.T.; Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Sayad, A. The Emerging Role of MicroRNA in Periodontitis: Pathophysiology, Clinical Potential and Future Molecular Perspectives. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, W.; Zhang, N.; Lin, Z. MicroRNA-125a-5p Modulates Macrophage Polarization by Targeting E26 Transformation-Specific Variant 6 Gene during Orthodontic Tooth Movement. Arch Oral Biol 2021, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, D.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, P.; Zheng, L.; Huang, Y.; Duan, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, Y. MiR-125-5p/IL-6R Axis Regulates Macrophage Inflammatory Response and Intestinal Epithelial Cell Apoptosis in Ulcerative Colitis through JAK1/STAT3 and NF-ΚB Pathway. Cell Cycle 2021, 20, 2547–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Tang, W.; Lu, R.; Tao, Y.; Ren, T.; Gao, Y. Human Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promote Lymphocyte Apoptosis and Alleviate Atherosclerosis via MiR-125b-1-3p/BCL11B Signal Axis. Ann Palliat Med 2021, 10, 2123–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, S.; Ma, X. Prognostic Value of MicroRNA-125 in Various Human Malignant Neoplasms: A Meta-Analysis. Clin Lab 2015, 61, 1667–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Gao, B.; Yue, J.; Liu, F.; Liu, Y.; Fu, W.; Si, Y. Exosomes from Mesenchymal Stem Cells Expressing MiR-125b Inhibit Neointimal Hyperplasia via Myosin IE. J Cell Mol Med 2019, 23, 1528–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowden Dahl, K.D.; Dahl, R.; Kruichak, J.N.; Hudson, L.G. The Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Responsive MiR-125a Represses Mesenchymal Morphology in Ovarian Cancer Cells. Neoplasia 2009, 11, 1208–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Yao, H.; Zheng, Z.; Qiu, G.; Sun, K. MiR-125b Targets BCL3 and Suppresses Ovarian Cancer Proliferation. Int J Cancer 2011, 128, 2274–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Guo, X.; Sun, S.; Lu, C.; Wang, L. Serum MiR-125b Levels Associated with Epithelial Ovarian Cancer (EOC) Development and Treatment Responses. Bioengineered 2020, 11, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Luo, J.; Cai, Q.; Pan, Q.; Zeng, H.; Guo, Z.; Dong, W.; Huang, J.; Lin, T. MicroRNA-125b Suppresses the Development of Bladder Cancer by Targeting E2F3. Int J Cancer 2011, 128, 1758–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pospisilova, S.; Pazzourkova, E.; Horinek, A.; Brisuda, A.; Svobodova, I.; Soukup, V.; Hrbacek, J.; Capoun, O.; Hanus, T.; Mares, J.; et al. MicroRNAs in Urine Supernatant as Potential Non-Invasive Markers for Bladder Cancer Detection. Neoplasma 2016, 63, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blick, C.; Ramachandran, A.; Mccormick, R.; Wigfield, S.; Cranston, D.; Catto, J.; Harris, A.L. Identification of a Hypoxia-Regulated MiRNA Signature in Bladder Cancer and a Role for MiR-145 in Hypoxia-Dependent Apoptosis. Br J Cancer 2015, 113, 634–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Tang, K.; Xiao, H.; Zeng, J.; Guan, W.; Guo, X.; Xu, H.; Ye, Z. A Panel of Eight-MiRNA Signature as a Potential Biomarker for Predicting Survival in Bladder Cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2015, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, Q.; Tang, S.; Xia, L.; Du, R.; Fan, R.; Gao, L.; Jin, J.; Liang, S.; Chen, Z.; Xu, G.; et al. Ectopic Expression of MiR-125a Inhibits the Proliferation and Metastasis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Targeting MMP11 and VEGF. PLoS One 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.Y.; Wang, Y.X.; Yan, W.T.; Li, H.Y.; Tian, Y.Z.; Wang, S.M.; Zhao, H.L. MicroRNA-125b Functions as a Tumor Suppressor in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2012, 13, 8762–8774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, L.; Wong, C.M.; Ying, Q.; Fan, D.N.Y.; Huang, S.; Ding, J.; Yao, J.; Yan, M.; Li, J.; Yao, M.; et al. MicroRNA-125b Suppressesed Human Liver Cancer Cell Proliferation and Metastasis by Directly Targeting Oncogene LIN28B2. Hepatology 2010, 52, 1731–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, J.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Wu, J.; Wu, N.; Chen, J.; Fang, F. MiR-125/Pokemon Auto-Circuit Contributes to the Progression of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Tumour Biol 2016, 37, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Zhang, L.Z.; Chen, Z.L.; Zhong, W.J.; Fang, J.H.; Zhu, Y.; Xiao, M.H.; Guo, Z.W.; Zhao, N.; He, X.; et al. A HMTR4-PDIA3P1-MiR-125/124-TRAF6 Regulatory Axis and Its Function in NF Kappa B Signaling and Chemoresistance. Hepatology 2020, 71, 1660–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.X.; Gao, S.; Pan, Y.Z.; Yu, C.; Sun, C.Y. Overexpression of MicroRNA-125b Sensitizes Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells to 5-Fluorouracil through Inhibition of Glycolysis by Targeting Hexokinase II. Mol Med Rep 2014, 10, 995–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Pei, C.; Cheng, H.; Song, K.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.; He, Y.; Liang, W.; Liu, B.; Tan, W.; et al. Comprehensive Analysis of FOXM1 Immune Infiltrates, M6a, Glycolysis and CeRNA Network in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front Immunol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wang, T.; Li, W.; Yin, S. MiR-125b Acts as a Tumor Suppressor of Melanoma by Targeting NCAM. JBUON 2021, 26, 182–188. [Google Scholar]

- Kappelmann, M.; Kuphal, S.; Meister, G.; Vardimon, L.; Bosserhoff, A.K. MicroRNA MiR-125b Controls Melanoma Progression by Direct Regulation of c-Jun Protein Expression. Oncogene 2013, 32, 2984–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, N.; Zhang, L.; Meisgen, F.; Harada, M.; Heilborn, J.; Homey, B.; Grandér, D.; Ståhle, M.; Sonkoly, E.; Pivarcsi, A. MicroRNA-125b down-Regulates Matrix Metallopeptidase 13 and Inhibits Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cell Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 29899–29908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, K.; Liu, W.; Zhang, J.; Fan, X.; Liu, J.; Zhao, N.; Yao, C.; Miao, G. MicroRNA-125b Exerts Antitumor Functions in Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma by Targeting the STAT3 Pathway. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sand, M.; Skrygan, M.; Sand, D.; Georgas, D.; Hahn, S.A.; Gambichler, T.; Altmeyer, P.; Bechara, F.G. Expression of MicroRNAs in Basal Cell Carcinoma. Br J Dermatol 2012, 167, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L. hong; Li, H.; Li, J. ping; Zhong, H.; Zhang, H. chon; Chen, J.; Xiao, T. MiR-125b Suppresses the Proliferation and Migration of Osteosarcoma Cells through down-Regulation of STAT3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2011, 416, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, B.; Yang, L.; Xue, J.; Zhang, Z.; Qin, L.; Bian, R. MiR-125b-5p/STAT3 Axis Regulates Drug Resistance in Osteosarcoma Cells by Acting on ABC Transporters. Stem Cells Int 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.Y.; Zheng, W.; Ding, M.; Guo, K.J.; Yuan, F.; Feng, H.; Deng, B.; Sun, W.; Hou, Y.; Gao, L. MiR-125b Acts as a Tumor Suppressor in Chondrosarcoma Cells by the Sensitization to Doxorubicin through Direct Targeting the ErbB2-Regulated Glucose Metabolism. Drug Des Devel Ther 2016, 10, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Sun, H.; Cheng, C.; Wang, G. BRCA1-Associated Protein-1 Suppresses Osteosarcoma Cell Proliferation and Migration Through Regulation PI3K/Akt Pathway. DNA Cell Biol 2017, 36, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Shen, W.; Yang, L.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, M.; Zong, F.; Geng, L.; Wang, Y.; Huang, T.; Pan, Y.; et al. Genetic Variations in MiR-125 Family and the Survival of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer in Chinese Population. Cancer Med 2019, 8, 2636–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Mao, W.; Zheng, S.; Ye, J. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Regulated MiR-125a-5p--a Metastatic Inhibitor of Lung Cancer. FEBS J 2009, 276, 5571–5578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagishita, S.; Fujita, Y.; Kitazono, S.; Ko, R.; Nakadate, Y.; Sawada, T.; Kitamura, Y.; Shimoyama, T.; Maeda, Y.; Takahashi, F.; et al. Chemotherapy-Regulated MicroRNA-125-HER2 Pathway as a Novel Therapeutic Target for Trastuzumab-Mediated Cellular Cytotoxicity in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2015, 14, 1414–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Wei, F.; Yu, J.; Zhao, H.; Jia, L.; Ye, Y.; Du, R.; Ren, X.; Li, H. Matrix Metalloproteinase 13: A Potential Intermediate between Low Expression of MicroRNA-125b and Increasing Metastatic Potential of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Genet 2015, 208, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloomston, M.; Frankel, W.L.; Petrocca, F.; Volinia, S.; Alder, H.; Hagan, J.P.; Liu, C.G.; Bhatt, D.; Taccioli, C.; Croce, C.M. MicroRNA Expression Patterns to Differentiate Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma from Normal Pancreas and Chronic Pancreatitis. JAMA 2007, 297, 1901–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Paris, P.L.; Chen, J.; Ngo, V.; Yao, H.; Frazier, M.L.; Killary, A.M.; Liu, C.G.; Liang, H.; Mathy, C.; et al. Next Generation Sequencing of Pancreatic Cyst Fluid MicroRNAs from Low Grade-Benign and High Grade-Invasive Lesions. Cancer Lett 2015, 356, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Wu, T.; Sheng, Y.; Dai, Y.; Xu, L.; Bao, C. Anti-Proliferative and Apoptosis-Promoting Effect of MicroRNA-125b on Pancreatic Cancer by Targeting NEDD9 via PI3K/AKT Signaling. Cancer Manag Res 2020, 12, 7363–7373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, B.A.; Valera, V.A.; Pinto, P.A.; Merino, M.J. Comprehensive MicroRNA Profiling of Prostate Cancer. J Cancer 2013, 4, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Dong, Y.; Wang, K.J.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, W.; Shen, H.F. Plasma Exosomal MiR-125a-5p and MiR-141-5p as Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Prostate Cancer. Neoplasma 2020, 67, 1314–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konoshenko, M.Y.; Lekchnov, E.A.; Bryzgunova, O.E.; Zaporozhchenko, I.A.; Yarmoschuk, S.V.; Pashkovskaya, O.A.; Pak, S.V.; Laktionov, P.P. The Panel of 12 Cell-Free MicroRNAs as Potential Biomarkers in Prostate Neoplasms. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.B.; Xue, L.; Yang, J.; Ma, A.H.; Zhao, J.; Xu, M.; Tepper, C.G.; Evans, C.P.; Kung, H.J.; White, R.W.D.V. An Androgen-Regulated MiRNA Suppresses Bak1 Expression and Induces Androgen-Independent Growth of Prostate Cancer Cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 19983–19988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.B.; Xue, L.; Ma, A.H.; Tepper, C.G.; Kung, H.J.; White, R.W.D. MiR-125b Promotes Growth of Prostate Cancer Xenograft Tumor through Targeting pro-Apoptotic Genes. Prostate 2011, 71, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Wu, J.; Ren, J.; Vlantis, A.C.; Li, M. yue; Liu, S.Y.W.; Ng, E.K.W.; Chan, A.B.W.; Luo, D.C.; Liu, Z.; et al. MicroRNA-125b Interacts with Foxp3 to Induce Autophagy in Thyroid Cancer. Mol Ther 2018, 26, 2295–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.G.; Wang, J.J.; Jiang, X.; Lan, J.P.; He, X.J.; Wang, H.J.; Ma, Y.Y.; Xia, Y.J.; Ru, G.Q.; Ma, J.; et al. MiR-125b Promotes Cell Migration and Invasion by Targeting PPP1CA-Rb Signal Pathways in Gastric Cancer, Resulting in a Poor Prognosis. Gastric Cancer 2015, 18, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Z.; Liu, N.; Lin, L.; Guo, X.; Yang, D.; Zhang, Q. MiR-125a-5p Inhibits Cell Proliferation and Induces Apoptosis in Colon Cancer via Targeting BCL2, BCL2L12 and MCL1. Biomed Pharmacother 2015, 75, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Pan, D.; Zhang, W.; Xu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, H.; Xu, J. Tumor MiR-125b Predicts Recurrence and Survival of Patients with Clear-Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma after Surgical Resection. Cancer Sci 2014, 105, 1427–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testa, U.; Pelosi, E. MicroRNAs Expressed in Hematopoietic Stem/Progenitor Cells Are Deregulated in Acute Myeloid Leukemias. Leuk Lymphoma 2015, 56, 1466–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemdehy, M.F.; Erkeland, S.J. MicroRNAs: Key Players of Normal and Malignant Myelopoiesis. Curr Opin Hematol 2012, 19, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattie, M.D.; Benz, C.C.; Bowers, J.; Sensinger, K.; Wong, L.; Scott, G.K.; Fedele, V.; Ginzinger, D.; Getts, R.; Haqq, C. Optimized High-Throughput MicroRNA Expression Profiling Provides Novel Biomarker Assessment of Clinical Prostate and Breast Cancer Biopsies. Mol Cancer 2006, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorio, M.V.; Ferracin, M.; Liu, C.G.; Veronese, A.; Spizzo, R.; Sabbioni, S.; Magri, E.; Pedriali, M.; Fabbri, M.; Campiglio, M.; et al. MicroRNA Gene Expression Deregulation in Human Breast Cancer. Cancer Res 2005, 65, 7065–7070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mar-Aguilar, F.; Luna-Aguirre, C.M.; Moreno-Rocha, J.C.; Araiza-Chávez, J.; Trevino, V.; Rodríguez-Padilla, C.; Reséndez-Pérez, D. Differential Expression of MiR-21, MiR-125b and MiR-191 in Breast Cancer Tissue. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2013, 9, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, F.; Yang, M.; Tong, N.; Fang, J.; Pan, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, X. Identification of Six Key MiRNAs Associated with Breast Cancer through Screening Large-Scale Microarray Data. Oncol Lett 2018, 16, 4159–4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braicu, C.; Raduly, L.; Morar-Bolba, G.; Cojocneanu, R.; Jurj, A.; Pop, L.A.; Pileczki, V.; Ciocan, C.; Moldovan, A.; Irimie, A.; et al. Aberrant MiRNAs Expressed in HER-2 Negative Breast Cancers Patient. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2018, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Incoronato, M.; Grimaldi, A.M.; Mirabelli, P.; Cavaliere, C.; Parente, C.A.; Franzese, M.; Staibano, S.; Ilardi, G.; Russo, D.; Soricelli, A.; et al. Circulating MiRNAs in Untreated Breast Cancer: An Exploratory Multimodality Morpho-Functional Study. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, G.K.; Goga, A.; Bhaumik, D.; Berger, C.E.; Sullivan, C.S.; Benz, C.C. Coordinate Suppression of ERBB2 and ERBB3 by Enforced Expression of Micro-RNA MiR-125a or MiR-125b. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 1479–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yan, L.X.; Wu, Q.N.; Du, Z.M.; Chen, J.; Liao, D.Z.; Huang, M.Y.; Hou, J.H.; Wu, Q.L.; Zeng, M.S.; et al. MiR-125b Is Methylated and Functions as a Tumor Suppressor by Regulating the ETS1 Proto-Oncogene in Human Invasive Breast Cancer. Cancer Res 2011, 71, 3552–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajabi, H.; Jin, C.; Ahmad, R.; McClary, A.C.; Joshi, M.D.; Kufe, D. MUCIN 1 ONCOPROTEIN EXPRESSION IS SUPPRESSED BY THE MiR-125b ONCOMIR. Genes Cancer 2010, 1, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

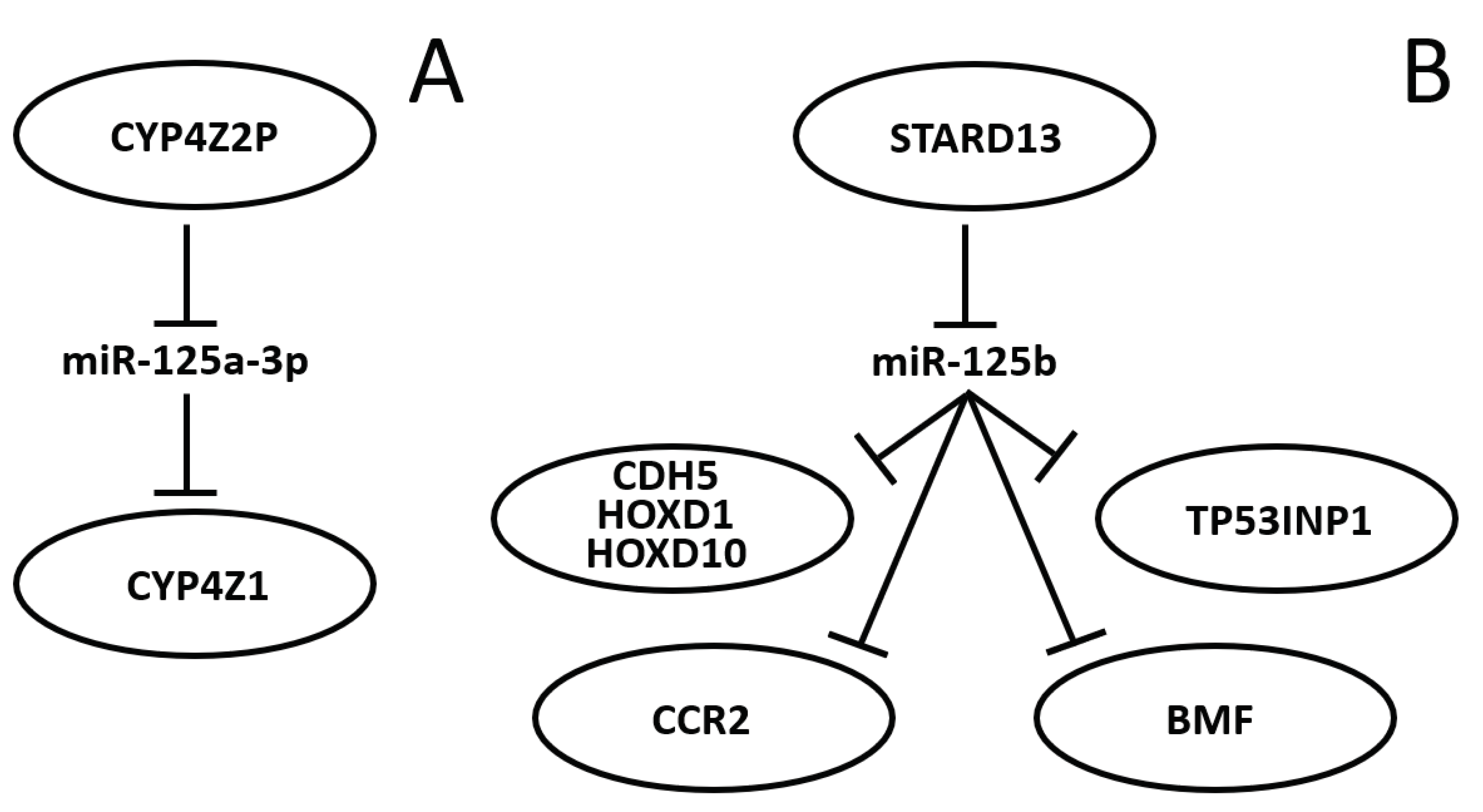

- Tang, F.; Zhang, R.; He, Y.; Zou, M.; Guo, L.; Xi, T. MicroRNA-125b Induces Metastasis by Targeting STARD13 in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Cells. PLoS One 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metheetrairut, C.; Adams, B.D.; Nallur, S.; Weidhaas, J.B.; Slack, F.J. Cel-Mir-237 and Its Homologue, Hsa-MiR-125b, Modulate the Cellular Response to Ionizing Radiation. Oncogene 2017, 36, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tan, G.; Dong, L.; Cheng, L.; Li, K.; Wang, Z.; Luo, H. Circulating MiR-125b as a Marker Predicting Chemoresistance in Breast Cancer. PLoS One 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Ding, Y.; Liu, H.; Xi, Y.; Xiong, W.; Li, G.; Lu, J.; Fodstad, O.; et al. MicroRNA-125b Confers the Resistance of Breast Cancer Cells to Paclitaxel through Suppression of pro-Apoptotic Bcl-2 Antagonist Killer 1 (Bak1) Expression. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 21496–21507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.; Xu, F.; Huang, W.; Luo, S.Y.; Lin, Y.T.; Zhang, G.H.; Du, Q.; Duan, R.H. MiR-125a-5p Expression Is Associated with the Age of Breast Cancer Patients. Genet Mol Res 2015, 14, 17927–17933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Fan, X.; Zhang, P.; Wang, P.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, J. MicroRNA-125b as a Tumor Suppressor by Targeting MMP11 in Breast Cancer. Thorac Cancer 2020, 11, 1613–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdollahzadeh, R.; Daraei, A.; Mansoori, Y.; Sepahvand, M.; Amoli, M.M.; Tavakkoly-Bazzaz, J. Competing Endogenous RNA (CeRNA) Cross Talk and Language in CeRNA Regulatory Networks: A New Look at Hallmarks of Breast Cancer. J Cell Physiol 2019, 234, 10080–10100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welch, J.D.; Baran-Gale, J.; Perou, C.M.; Sethupathy, P.; Prins, J.F. Pseudogenes Transcribed in Breast Invasive Carcinoma Show Subtype-Specific Expression and CeRNA Potential. BMC Genomics 2015, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, K.; Wang, Q.; Wang, L. Analysis of Competitive Endogenous RNA Regulatory Network of Exosomal Breast Cancer Based on ExoRBase. Evolutionary Bioinformatics 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieger, M.A.; Ebner, R.; Bell, D.R.; Kiessling, A.; Rohayem, J.; Schmitz, M.; Temme, A.; Rieber, E.P.; Weigle, B. Identification of a Novel Mammary-Restricted Cytochrome P450, CYP4Z1, with Overexpression in Breast Carcinoma. Cancer Res 2004, 64, 2357–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Chai, H.; Li, Y.; Zhao, H.; Xie, X.; Zheng, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Yang, G.; Cai, X.; et al. Increased Expression of CYP4Z1 Promotes Tumor Angiogenesis and Growth in Human Breast Cancer. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2012, 264, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Li, X.; Gu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Xi, T. Pseudogene CYP4Z2P 3’UTR Promotes Angiogenesis in Breast Cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014, 453, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Li, X.; Gu, Y.; Lv, X.; Xi, T. The 3’UTR of the Pseudogene CYP4Z2P Promotes Tumor Angiogenesis in Breast Cancer by Acting as a CeRNA for CYP4Z1. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015, 150, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Li, X.; Gu, Y.; Lv, X.; Xi, T. Correction to: The 3′UTR of the Pseudogene CYP4Z2P Promotes Tumor Angiogenesis in Breast Cancer by Acting as a CeRNA for CYP4Z1 (Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, (2015), 150, 1, (105-118), 10.1007/S10549-015-3298-2). Breast Cancer Res Treat 2020, 179, 521–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Li, X.; Meng, X.; Chou, J.; Hu, J.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Xing, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xi, T. Competing Endogenous RNA Networks of CYP4Z1 and Pseudogene CYP4Z2P Confer Tamoxifen Resistance in Breast Cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2016, 427, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zheng, L.; Xin, Y.; Tan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Meng, X.; Wang, Z.; Xi, T. The Competing Endogenous RNA Network of CYP4Z1 and Pseudogene CYP4Z2P Exerts an Anti-Apoptotic Function in Breast Cancer. FEBS Lett 2017, 591, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Guo, Q.; Xiang, C.; Liu, S.; Jiang, Y.; Gao, L.; Ni, H.; Wang, T.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, H.; et al. Transcriptional Factor Six2 Promotes the Competitive Endogenous RNA Network between CYP4Z1 and Pseudogene CYP4Z2P Responsible for Maintaining the Stemness of Breast Cancer Cells. J Hematol Oncol 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Guo, Q.; Xiang, C.; Liu, S.; Jiang, Y.; Gao, L.; Ni, H.; Wang, T.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, H.; et al. Correction to: Transcriptional Factor Six2 Promotes the Competitive Endogenous RNA Network between CYP4Z1 and Pseudogene CYP4Z2P Responsible for Maintaining the Stemness of Breast Cancer Cells (Journal of Hematology and Oncology (2019) 12 (23). https://doi.org/10.1186/S13045-019-0697-6). [CrossRef]

- Ching, Y.P.; Wong, C.M.; Chan, S.F.; Leung, T.H.Y.; Ng, D.C.H.; Jin, D.Y.; Ng, I.O.L. Deleted in Liver Cancer (DLC) 2 Encodes a RhoGAP Protein with Growth Suppressor Function and Is Underexpressed in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 10824–10830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Chen, N.T.; Shih, Y.P.; Liao, Y.C.; Xue, L.; Lo, S.H. DLC2 Modulates Angiogenic Responses in Vascular Endothelial Cells by Regulating Cell Attachment and Migration. Oncogene 2010, 29, 3010–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullmannova, V.; Popescu, N.C. Expression Profile of the Tumor Suppressor Genes DLC-1 and DLC-2 in Solid Tumors. Int J Oncol 2006, 29, 1127–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, S.; Khalil, B.; Nasrallah, A.; Saykali, B.A.; Sobh, R.; Nasser, S.; El-Sibai, M. StarD13 Is a Tumor Suppressor in Breast Cancer That Regulates Cell Motility and Invasion. Int J Oncol 2014, 44, 1499–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ippolito, E.; Plantamura, I.; Bongiovanni, L.; Casalini, P.; Baroni, S.; Piovan, C.; Orlandi, R.; Gualeni, A.V.; Gloghini, A.; Rossini, A.; et al. MiR-9 and MiR-200 Regulate PDGFRβ-Mediated Endothelial Differentiation of Tumor Cells in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Res 2016, 76, 5562–5572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Li, X.; Guo, X.; Guo, Q.; Xiang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Xing, Y.; Xi, T.; Zheng, L. The CCR2 3’UTR Functions as a Competing Endogenous RNA to Inhibit Breast Cancer Metastasis. J Cell Sci 2017, 130, 3399–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, P.; Leslie, H.; Dillon, R.L.; Muller, W.J.; Raouf, A.; Mowat, M.R.A. In Vivo Evidence Supporting a Metastasis Suppressor Role for Stard13 (Dlc2) in ErbB2 (Neu) Oncogene Induced Mouse Mammary Tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2018, 57, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.; Liu, X.; Xiong, B.; Sun, Y. Homeobox B4 Inhibits Breast Cancer Cell Migration by Directly Binding to StAR-Related Lipid Transfer Domain Protein 13. Oncol Lett 2017, 14, 4625–4632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Xiang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Xi, T.; Zheng, L. Displacement of Bax by BMF Mediates STARD13 3’UTR-Induced Breast Cancer Cells Apoptosis in an MiRNA-Depedent Manner. Mol Pharm 2018, 15, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Xie, T.; Xiang, C.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. A Positive TGF-β/MiR-9 Regulatory Loop Promotes the Expansion and Activity of Tumour-Initiating Cells in Breast Cancer. Br J Pharmacol 2023, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amirfallah, A.; Knutsdottir, H.; Arason, A.; Hilmarsdottir, B.; Johannsson, O.T.; Agnarsson, B.A.; Barkardottir, R.B.; Reynisdottir, I. Hsa-MiR-21-3p Associates with Breast Cancer Patient Survival and Targets Genes in Tumor Suppressive Pathways. PLoS One 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Xiang, C.; Li, X.; Guo, Q.; Gao, L.; Ni, H.; Xia, Y.; Xi, T. STARD13-Correlated CeRNA Network-Directed Inhibition on YAP/TAZ Activity Suppresses Stemness of Breast Cancer via Co-Regulating Hippo and Rho-GTPase/F-Actin Signaling. J Hematol Oncol 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, F.; Hu, J.; Chou, J.; Liu, Y.; Xing, Y.; Xi, T. STARD13-Correlated CeRNA Network Inhibits EMT and Metastasis of Breast Cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 23197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, F.; Zhang, R.; He, Y.; Zou, M.; Guo, L.; Xi, T. MicroRNA-125b Induces Metastasis by Targeting STARD13 in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Cells. PLoS One 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Li, X.; Guo, X.; Guo, Q.; Xiang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Xing, Y.; Xi, T.; Zheng, L. The CCR2 3’UTR Functions as a Competing Endogenous RNA to Inhibit Breast Cancer Metastasis. J Cell Sci 2017, 130, 3399–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seillier, M.; Peuget, S.; Gayet, O.; Gauthier, C.; N’Guessan, P.; Monte, M.; Carrier, A.; Iovanna, J.L.; Dusetti, N.J. TP53INP1, a Tumor Suppressor, Interacts with LC3 and ATG8-Family Proteins through the LC3-Interacting Region (LIR) and Promotes Autophagy-Dependent Cell Death. Cell Death Differ 2012, 19, 1525–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seux, M.; Peuget, S.; Montero, M.P.; Siret, C.; Rigot, V.; Clerc, P.; Gigoux, V.; Pellegrino, E.; Pouyet, L.; N’Guessan, P.; et al. TP53INP1 Decreases Pancreatic Cancer Cell Migration by Regulating SPARC Expression. Oncogene 2011 30:27 2011, 30, 3049–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Li, X.; Chou, J.; Xiang, C.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, X.; Gao, L.; Xing, Y.; Xi, T. StarD13 3’-Untranslated Region Functions as a CeRNA for TP53INP1 in Prohibiting Migration and Invasion of Breast Cancer Cells by Regulating MiR-125b Activity. Eur J Cell Biol 2018, 97, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Xiang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Xi, T.; Zheng, L. Displacement of Bax by BMF Mediates STARD13 3’UTR-Induced Breast Cancer Cells Apoptosis in an MiRNA-Depedent Manner. Mol Pharm 2018, 15, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puthalakath, H.; Villunger, A.; O’Reilly, L.A.; Beaumont, J.G.; Coultas, L.; Cheney, R.E.; Huang, D.C.S.; Strasser, A. Bmf: A Proapoptotic BH3-Only Protein Regulated by Interaction with the Myosin V Actin Motor Complex, Activated by Anoikis. Science 2001, 293, 1829–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Jia, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, X.; Song, L.; Wu, Y.; Wang, A.; Chen, W.; Wang, S.; Lu, Y. Tanshinone IIA Attenuates the Stemness of Breast Cancer Cells via Targeting the MiR-125b/STARD13 Axis. Exp Hematol Oncol 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkley, D.; Rao, A.; Pour, M.; França, G.S.; Yanai, I. Cancer Cell States and Emergent Properties of the Dynamic Tumor System. Genome Res 2021, 31, 1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Official Journal of the European Union. Notices From European Union Institutions, Bodies, Offices And Agencies. Council conclusions on personalised medicine for patients (2015/C 421/03). Issued on 17th December 2015. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52015XG1217 (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Salari, P.; Larijani, B. Ethical Issues Surrounding Personalized Medicine: A Literature Review. Acta Med. Iran. 2017, 55, 209–217. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore, R.N.; Goodman, K.W. Precision Medicine Ethics: Selected Issues and Developments in next-Generation Sequencing, Clinical Oncology, and Ethics. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2016, 28, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswami, R.; Bayer, R.; Galea, S. Precision Medicine from a Public Health Perspective. Annu Rev Public Health 2018, 39, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council. Issued in February 2022. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-02/eu_cancer-plan_en_0.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- European Commission. Directorate General for Research and Innovation. Conquering Cancer: Mission Possible; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2020. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/b389aad3-fd56-11ea-b44f-01aa75ed71a1/https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/b389aad3-fd56-11ea-b44f-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Hickman, J.A.; Tannock, I.F.; Meheus, L.; Hutchinson, L. The European Union and personalised cancer medicine. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 150, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, S.; van Delden, J.J.M.; van Diest, P.J.; Bredenoord, A.L. Moral Duties of Genomics Researchers: Why Personalized Medicine Requires a Collective Approach. Trends Genet 2017, 33, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morsella, A.; Cadeddu, C.; Castagna, C.; Hoxhaj, I.; Sassano, M.; Wang, C.M.; Wang, L.; Klessova, S.; de Belvis, A.G.; Boccia, S.; et al. “Integrating China in the International Consortium for Personalized Medicine”: The Coordination and Support Action to Foster Collaboration in Personalized Medicine Development between Europe and China. Public Health Genom. 2021, 24, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGowan, M.L.; Settersten, R.A.; Juengst, E.T.; Fishman, J.R. Integrating genomics into clinical oncology: Ethical and social challenges from proponents of personalized medicine. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2014, 32, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Smart Specialisation Platform. European Partnership on Personalised Medicine. TOPIC ID: HORIZON-HLTH-2023-CARE-08-01. Last Updated on Aug 9, 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/funding-tenders/opportunities/portal/screen/opportunities/topic-details/horizon-hlth-2023-care-08-01 (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Venne, J.; Busshoff, U.; Poschadel, S.; Menschel, R.; Evangelatos, N.; Vysyaraju, K.; Brand, A. International Consortium for Personalized Medicine: An International Survey about the Future of Personalized Medicine. Per. Med. 2020, 17, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brothers, K.B.; Rothstein, M.A. Ethical, legal and social implications of incorporating personalized medicine into healthcare. Per. Med. 2015, 12, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicente, A.M.; Ballensiefen, W.; Jönsson, J.-I. How Personalised Medicine Will Transform Healthcare by 2030: The ICPerMed Vision. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisodiya, S.M. Precision Medicine and Therapies of the Future. Epilepsia 2021, 62 Suppl 2, S90–S105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmesgern, E.; Norstedt, I.; Draghia-Akli, R. Enabling Personalized Medicine in Europe by the European Commission’s Funding Activities. Per. Med. 2017, 14, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, D.; Bernini, C.; Thomas, P.P.M.; Morre, S.A. Cooperating on Data: The Missing Element in Bringing Real Innovation to Europe’s Healthcare Systems. Public Health Genom. 2019, 22, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.Y.; Ge, D.; He, M.M. Big Data Analytics for Genomic Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medenica, S.; Zivanovic, D.; Batkoska, L.; Marinelli, S.; Basile, G.; Perino, A.; Cucinella, G.; Gullo, G.; Zaami, S. The Future Is Coming: Artificial Intelligence in the Treatment of Infertility Could Improve Assisted Reproduction Outcomes-The Value of Regulatory Frameworks. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12, 2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharrer, G.T. Personalized Medicine: Ethical Aspects. Methods Mol Biol 2017, 1606, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brittain, H.K.; Scott, R.; Thomas, E. The Rise of the Genome and Personalised Medicine. Clin Med (Lond) 2017, 17, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borry, P.; Bentzen, H.B.; Budin-Ljøsne, I.; Cornel, M.C.; Howard, H.C.; Feeney, O.; Jackson, L.; Mascalzoni, D.; Mendes, Á.; Peterlin, B.; et al. The Challenges of the Expanded Availability of Genomic Information: An Agenda-Setting Paper. J. Community Genet. 2018, 9, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, M.; Awan, F.M.; Naz, A.; deAndrés-Galiana, E.J.; Alvarez, O.; Cernea, A.; Fernández-Brillet, L.; Fernández-Martínez, J.L.; Kloczkowski, A. Innovations in Genomics and Big Data Analytics for Personalized Medicine and Health Care: A Review. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, M.E.; Parvez, M.M.; Shin, J.-G. Clinical Implementation of Pharmacogenomics for Personalized Precision Medicine: Barriers and Solutions. J Pharm Sci 2017, 106, 2368–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavan, S.P.; Thompson, A.J.; Payne, K. The Economic Case for Precision Medicine. Expert Rev. Precis. Med. Drug Dev. 2018, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piersanti, V.; Consalvo, F.; Signore, F.; Del Rio, A.; Zaami, S. Surrogacy and “Procreative Tourism”. What Does the Future Hold from the Ethical and Legal Perspectives? Medicina (Kaunas) 2021, 57, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Deng, B.; Morrison, A.M.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A.; Yang, L. Medical, Health and Wellness Tourism Research-A Review of the Literature (1970-2020) and Research Agenda. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 10875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callier, S.L.; Abudu, R.; Mehlman, M.J.; Singer, M.E.; Neuhauser, D.; Caga-Anan, C.; Wiesner, G.L. Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications of Personalized Genomic Medicine Research: Current Literature and Suggestions for the Future. Bioethics 2016, 30, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varone, M.C.; Napoletano, G.; Negro, F. Decellularization and Tissue Engineering: Viable Therapeutic Prospects for Transplant Patients and Infertility? Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2021, 25, 6164–6166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, H.B.; McQuilling, J.P.; King, N.M.P. Ethical Considerations in Tissue Engineering Research: Case Studies in Translation. Methods 2016, 99, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchant, G.E.; Lindor, R.A. Personalized medicine and genetic malpractice. Genet. Med. 2013, 15, 921–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, S.D.; Viel, G. [Personalized medicine and medical malpractice.]. G Ital Med Lav Ergon 2017, 39, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marchant, G.; Barnes, M.; Evans, J.P.; LeRoy, B.; Wolf, S.M. ; LawSeq Liability Task Force From Genetics to Genomics: Facing the Liability Implications in Clinical Care. J. Law Med. Ethics 2020, 48, 11–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledford, H. US Personalized-Medicine Industry Takes Hit from Supreme Court. Nature 2016, 536, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donohue, K.E.; Gooch, C.; Katz, A.; Wakelee, J.; Slavotinek, A.; Korf, B.R. Pitfalls and Challenges in Genetic Test Interpretation: An Exploration of Genetic Professionals Experience with Interpretation of Results. Clin Genet 2021, 99, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, Y.A.; Senner, G.D.; Marchant, G.E. Physicians’ Duty to Recontact and Update Genetic Advice. Per Med 2017, 14, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otten, E.; Plantinga, M.; Birnie, E.; Verkerk, M.A.; Lucassen, A.M.; Ranchor, A.V.; Van Langen, I.M. Is There a Duty to Recontact in Light of New Genetic Technologies? A Systematic Review of the Literature. Genet Med 2015, 17, 668–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.L.; Foulkes, A.L. GENETIC DUTIES. William Mary Law Rev 2020, 62, 143–211. [Google Scholar]

- Niida, A.; Iwasaki, W.M.; Innan, H. Neutral Theory in Cancer Cell Population Genetics. Mol Biol Evol 2018, 35, 1316–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-David, U.; Amon, A. Context Is Everything: Aneuploidy in Cancer. Nat Rev Genet 2020, 21, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newburger, D.E.; Kashef-Haghighi, D.; Weng, Z.; Salari, R.; Sweeney, R.T.; Brunner, A.L.; Zhu, S.X.; Guo, X.; Varma, S.; Troxell, M.L.; et al. Genome Evolution during Progression to Breast Cancer. Genome Res 2013, 23, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, F.; Tsuboi, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Horimoto, Y.; Mogushi, K.; Ito, T.; Emi, M.; Matsubara, D.; Shibata, T.; Saito, M.; et al. Short Somatic Alterations at the Site of Copy Number Variation in Breast Cancer. Cancer Sci 2021, 112, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soysal, S.D.; Tzankov, A.; Muenst, S.E. Role of the Tumor Microenvironment in Breast Cancer. Pathobiology 2015, 82, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinshaw, D.C.; Shevde, L.A. The Tumor Microenvironment Innately Modulates Cancer Progression. Cancer Res 2019, 79, 4557–4567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Z.; Kan, C.; Sun, M.; Yang, F.; Wong, M.; Wang, S.; Zheng, H. Mapping Breast Cancer Microenvironment Through Single-Cell Omics. Front Immunol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boo, L.; Ho, W.Y.; Ali, N.M.; Yeap, S.K.; Ky, H.; Chan, K.G.; Yin, W.F.; Satharasinghe, D.A.; Liew, W.C.; Tan, S.W.; et al. Phenotypic and MicroRNA Transcriptomic Profiling of the MDA-MB-231 Spheroid-Enriched CSCs with Comparison of MCF-7 MicroRNA Profiling Dataset. PeerJ 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahram, M.; Mustafa, E.; Zaza, R.; Abu Hammad, S.; Alhudhud, M.; Bawadi, R.; Zihlif, M. Differential Expression and Androgen Regulation of MicroRNAs and Metalloprotease 13 in Breast Cancer Cells. Cell Biol Int 2017, 41, 1345–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tumor | Node | Metastasis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tx | no primary tumor information | Nx | not assessable | Mx | not assessed |

| T0 | no primary tumor evidence | N0 | no clinically positive nodes | M0 | no evidence |

| TIS | carcinoma in-situ (primary sites) | N1 | single, ipsilateral, size <3 cm | M1 | metastasis present at distance |

| T1 | size <2 cm | N2a | single, ipsilateral, size 3-6 cm | ||

| T2 | size 2 to 4cm | N2b | multiple, ipsilateral, size <6 cm | ||

| T3 | size >4 cm | N3 | massive/ipsilateral/bilateral/controlateral | ||

| T4 | size >4 cm, pterygoid muscle, base of tongue or skin involved | N3a | ipsilateral node(s), one more than 6 cm | ||

| N3b | bilateral | ||||

| N4 | controlateral | ||||

| Stakeholder(s) involved | Outcome(s) to be pursued |

|---|---|

| European countries/regions in cooperation with international partners | Broad-ranging collaborative research efforts for the development of innovative personalized medicine approaches regarding prevention, diagnosis and treatment |

| Healthcare authorities, policymakers |

|

| Healthcare industries and manufacturers, policymakers |

|

| Healthcare providers and professionals | Improvement of health outcomes, prevention of diseases and foster population health through the equitable and cost-effective implementation of personalized medicine |

| Connected local/regional ecosystems of stakeholders | Fostering the uptake of successful innovations in personalized medicine, in order to improve healthcare outcomes and strengthening European competitiveness |

| Citizens, patients and healthcare professionals | Broader knowledge of personalized medicine and resulting better involvement in its implementation through feedback |

| All stakeholders | Better cooperation and establishment of networks of national and regional knowledge and awareness-building hubs for personalized medicine. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).