Submitted:

26 September 2023

Posted:

27 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Context

2.2. Study Design and Population

2.3. Assessment tools

- a)

- Section 1 included information on the study, privacy protection, and informed consent.

- b)

- Section 2 included the participants’ demographic backgrounds, including age, education, work, marital status, number of children, working activity, and socio-economic status. The history of life-events included: the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, complex management of family life and work during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the impact produced by the 2009 L’Aquila earthquake measured on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = None; 1 = Only a little; 2 = To some extent; 3 = Considerably; 4 = Greatly). Previous contact with mental health services, mental health issues, and treatments were also assessed.

- c)

- Section 3 included standardized questionnaires investigating the quality of life, psychopathology, family functioning, and family burden.

2.4. Statistical analyses

3. Results

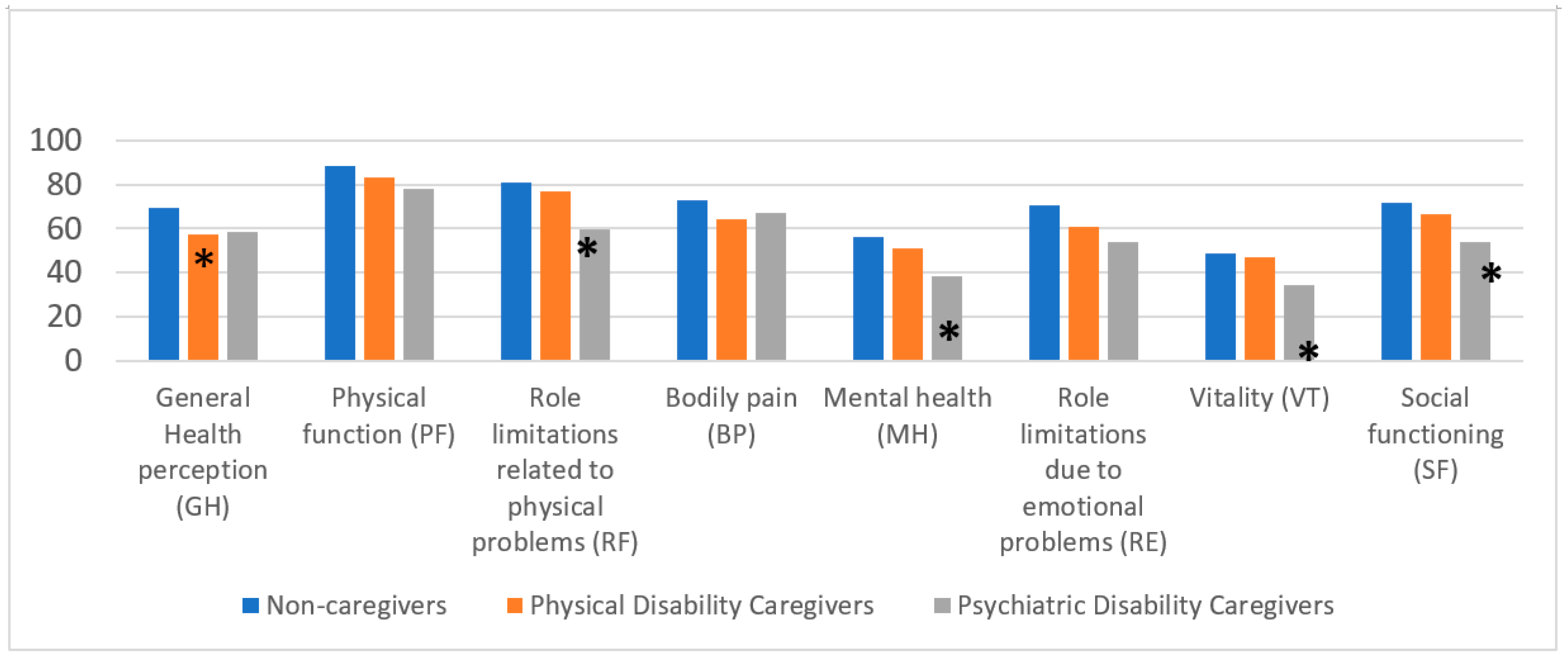

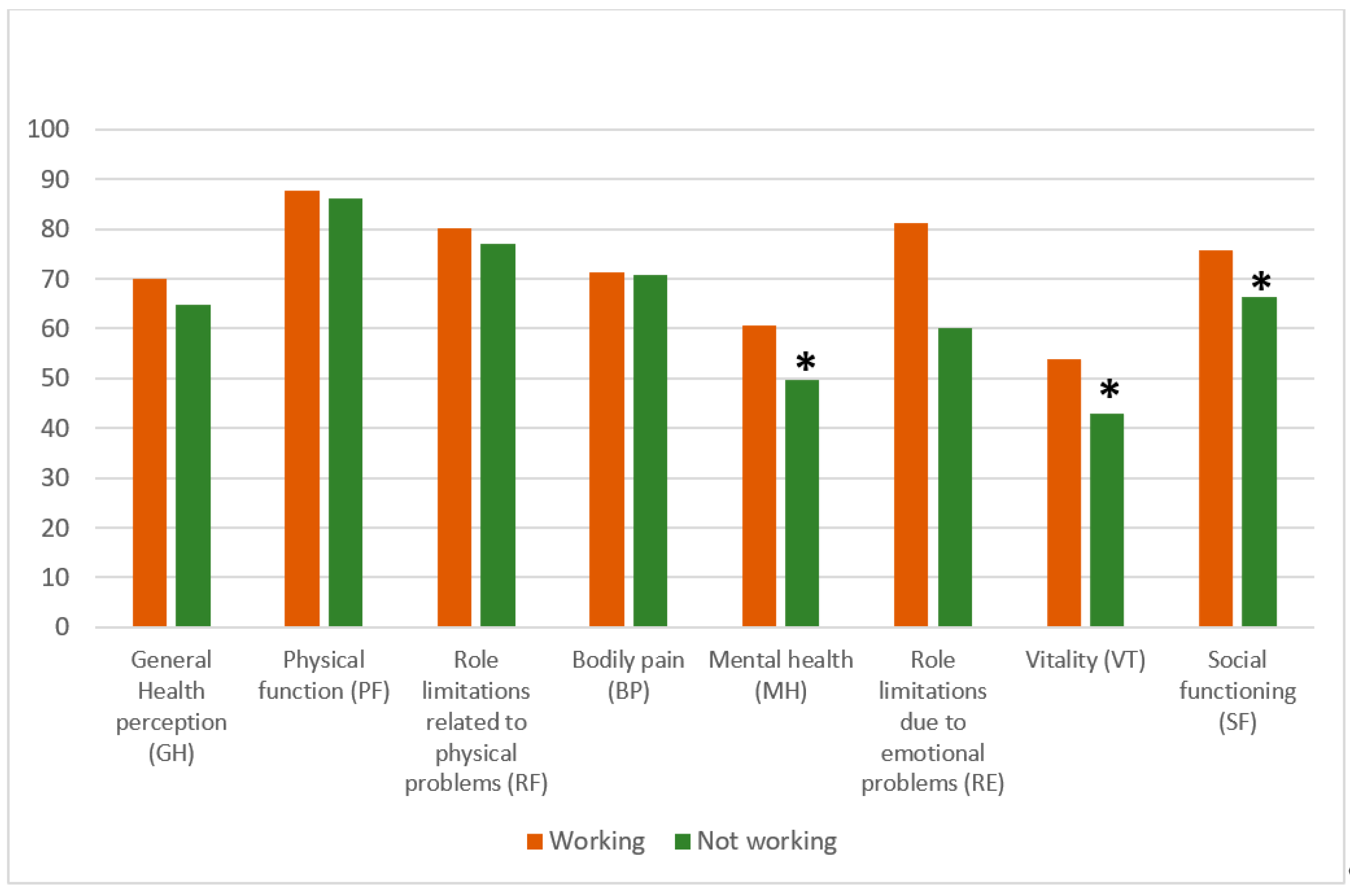

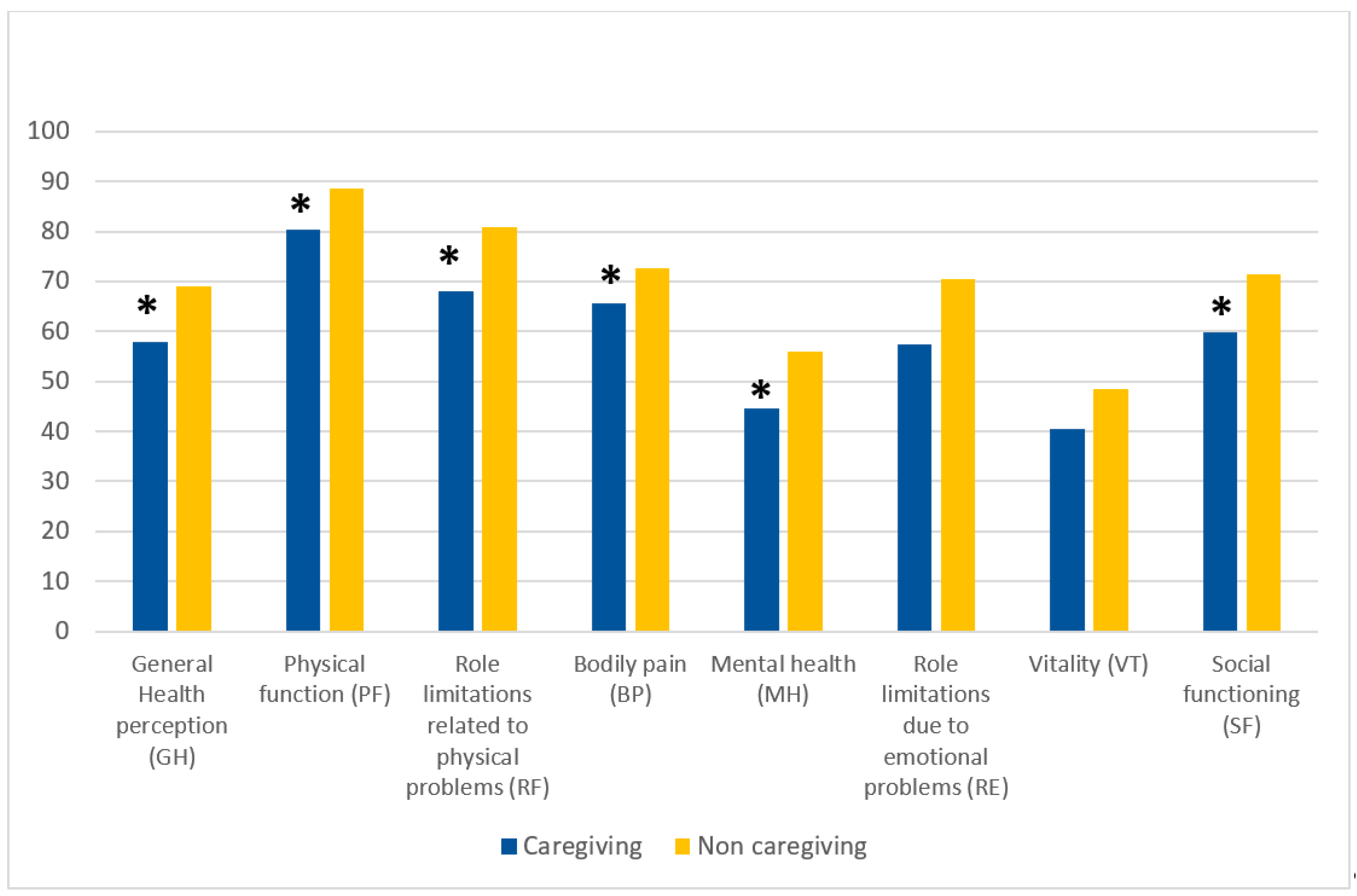

3.1. Socio-demographic and characteristics of the sample, depression, health-related quality of life, and family functioning

| Variables included | Workers (n=73) |

Non-workers (n=138) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD)* | 41.8 (13.2) | 32.4 (20.1) |

| Working conditions (%) | ||

| Self-employed/freelancers | 23 (31.5) | |

| Full-time work | 35 (47.9) | |

| Part-time work | 15 (20.5) | |

| Student | - | 91 (65.9) |

| Housewife | - | 13 (9.4) |

| Unemployed | - | 12 (8.7) |

| Retired | - | 22 (15.9) |

| Nationality (%) | ||

| Non-EU citizens | 4 (5.5) | 4 (2.9) |

| Marital status (%)* | ||

| Single | 16 (21.9) | 77 (55.8) |

| Married/Partnership | 49 (67.1) | 50 (36.2) |

| Separated/ Divorced | 7 (9.6) | 4 (2.9) |

| Widowed | 1 (1.4) | 7 (5.1) |

| Parents of children (%)* | 33 (45.2) | 32 (23.2) |

| Level of education (%)* | ||

| >13 years (graduated) | 24 (32.9) | 96 (69.6) |

| Socio-economic status (%) | ||

| High- upper middle income | 39 (53.4) | 56 (40.6) |

| Middle - low income | 27 (40.2) | 57 (41.3) |

| Struggling financially | 7 (9.6) | 25 (18.1) |

3.2. Correlations between age, years of education, health-related quality of life, family functioning, and burden of care

3.3. Variables impacting severe depressive symptomatology

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and limitation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shockley, K.M.; Clark, M.A.; Dodd, H.; King, E.B. Work-family strategies during COVID-19: Examining gender dynamics among dual-earner couples with young children. J Appl Psychol 2021, 106, 15-28. [CrossRef]

- Wanberg, C.R.; Csillag, B.; Douglass, R.P.; Zhou, L.; Pollard, M.S. Socioeconomic status and well-being during COVID-19: A resource-based examination. J Appl Psychol 2020, 105, 1382-1396. [CrossRef]

- Pai, N.; Vella, S.L. COVID-19 and loneliness: A rapid systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2021, 55, 1144-1156. [CrossRef]

- Lampraki, C.; Hoffman, A.; Roquet, A.; Jopp, D.S. Loneliness during COVID-19: Development and influencing factors. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0265900. [CrossRef]

- Currin, J.M.; Evans, A.E.; Miller, B.M.; Owens, C.; Giano, Z.; Hubach, R.D. The impact of initial social distancing measures on individuals' anxiety and loneliness depending on living with their romantic/sexual partners. Curr Psychol 2022, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Shen, B.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Z.; Xie, B.; Xu, Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr 2020, 33, e100213. [CrossRef]

- Giusti, L.; Salza, A.; Mammarella, S.; Bianco, D.; Ussorio, D.; Casacchia, M.; Roncone, R. #Everything Will Be Fine. Duration of Home Confinement and "All-or-Nothing" Cognitive Thinking Style as Predictors of Traumatic Distress in Young University Students on a Digital Platform During the COVID-19 Italian Lockdown. Front Psychiatry 2020, 11, 574812. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17. [CrossRef]

- Horesh, D.; Brown, A.D. Traumatic stress in the age of COVID-19: A call to close critical gaps and adapt to new realities. Psychol Trauma 2020, 12, 331-335. [CrossRef]

- Lima, C.K.T.; Carvalho, P.M.M.; Lima, I.; Nunes, J.; Saraiva, J.S.; de Souza, R.I.; da Silva, C.G.L.; Neto, M.L.R. The emotional impact of Coronavirus 2019-nCoV (new Coronavirus disease). Psychiatry Res 2020, 287, 112915. [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, R.P. COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr 2020, 52, 102066. [CrossRef]

- Alzueta, E.; Perrin, P.; Baker, F.C.; Caffarra, S.; Ramos-Usuga, D.; Yuksel, D.; Arango-Lasprilla, J.C. How the COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives: A study of psychological correlates across 59 countries. J Clin Psychol 2021, 77, 556-570. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.Z.; Wong, J.Y.H.; Luk, T.T.; Wai, A.K.C.; Lam, T.H.; Wang, M.P. Mental health crisis under COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong, China. Int J Infect Dis 2020, 100, 431-433. [CrossRef]

- Cecchini, J.A.; Carriedo, A.; Fernandez-Rio, J.; Mendez-Gimenez, A.; Gonzalez, C.; Sanchez-Martinez, B.; Rodriguez-Gonzalez, P. A longitudinal study on depressive symptoms and physical activity during the Spanish lockdown. Int J Clin Health Psychol 2021, 21, 100200. [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, V.; Giusti, L.; Salza, A.; Cofini, V.; Cifone, M.G.; Casacchia, M.; Fabiani, L.; Roncone, R. Moderate Depression Promotes Posttraumatic Growth (Ptg): A Young Population Survey 2 Years after the 2009 L'Aquila Earthquake. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 2017, 13, 10-19. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Leng, Y.; Guo, Y.; Yang, J.; Cui, Q.; Geng, B.; Hu, H.; Zhou, Y. Association between earthquake experience and depression 37 years after the Tangshan earthquake: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026110. [CrossRef]

- Mazza, C.; Ricci, E.; Biondi, S.; Colasanti, M.; Ferracuti, S.; Napoli, C.; Roma, P. A Nationwide Survey of Psychological Distress among Italian People during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17. [CrossRef]

- Pancani, L.; Marinucci, M.; Aureli, N.; Riva, P. Forced Social Isolation and Mental Health: A Study on 1,006 Italians Under COVID-19 Lockdown. Front Psychol 2021, 12, 663799. [CrossRef]

- Carpiniello, B.; Tusconi, M.; Zanalda, E.; Di Sciascio, G.; Di Giannantonio, M.; Executive Committee of The Italian Society of, P. Psychiatry during the Covid-19 pandemic: a survey on mental health departments in Italy. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 593. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.; Shrestha, A.D.; Stojanac, D.; Miller, L.J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women's mental health. Arch Women Ment Hlth 2020, 23, 741-748. [CrossRef]

- Thibaut, F.; van Wijngaarden-Cremers, P.J.M. Women's Mental Health in the Time of Covid-19 Pandemic. Front Glob Womens Health 2020, 1, 588372. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, L.L.; Zhao, S.J.; Kwak-Kim, J.; Mor, G.; Liao, A.H. Why are pregnant women susceptible to COVID-19? An immunological viewpoint. J Reprod Immunol 2020, 139, 103122. [CrossRef]

- Santomauro, D.F.; Mantilla Herrera, A.M.; Shadid, J.; Zheng, P.; Ashbaugh, C.; Pigott, D.M.; Abbafati, C.; Adolph, C.; Amlag, J.O.; Aravkin, A.Y.; et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet 2021, 398, 1700-1712. [CrossRef]

- Street, A.E.; Dardis, C.M. Using a social construction of gender lens to understand gender differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin Psychol Rev 2018, 66, 97-105. [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Tan, W.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, X.; Zou, Y.; Hu, Y.; Luo, X.; Jiang, X.; McIntyre, R.S.; et al. Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown? A case-control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry. Brain Behav Immun 2020, 87, 100-106. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.M. An increasing risk of family violence during the Covid-19 pandemic: Strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Science International: Reports 2020, 2. [CrossRef]

- Romito, P.; Pellegrini, M.; Saurel-Cubizolles, M.J. Intimate Partner Violence Against Women During the COVID-19 Lockdown in Italy: A Multicenter Survey Involving Anti-Violence Centers. Violence Against Women 2022, 28, 2186-2203. [CrossRef]

- Piquero, A.R.; Jennings, W.G.; Jemison, E.; Kaukinen, C.; Knaul, F.M. Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic - Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Criminal Justice 2021, 74. [CrossRef]

- Leroy, S.; Schmidt, A.M.; Madjar, N. Working from home during COVID-19: A study of the interruption landscape. J Appl Psychol 2021, 106, 1448-1465. [CrossRef]

- Loezar-Hernandez, M.; Briones-Vozmediano, E.; Ronda-Perez, E.; Otero-Garcia, L. Juggling during Lockdown: Balancing Telework and Family Life in Pandemic Times and Its Perceived Consequences for the Health and Wellbeing of Working Women. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20. [CrossRef]

- Matthews, T.A.; Chen, L.; Omidakhsh, N.; Zhang, D.; Han, X.; Chen, Z.; Shi, L.; Li, Y.; Wen, M.; Li, H.; et al. Gender difference in working from home and psychological distress - A national survey of U.S. employees during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ind Health 2022, 60, 334-344. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Becerik-Gerber, B.; Lucas, G.; Roll, S.C. Impacts of Working From Home During COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical and Mental Well-Being of Office Workstation Users. J Occup Environ Med 2021, 63, 181-190. [CrossRef]

- Möhring, K.; Naumann, E.; Reifenscheid, M.; Wenz, A.; Rettig, T.; Krieger, U.; Friedel, S.; Finkel, M.; Cornesse, C.; Blom, A.G. The COVID-19 pandemic and subjective well-being: longitudinal evidence on satisfaction with work and family. European Societies 2020, 23, S601-S617. [CrossRef]

- Burn, E.; Tattarini, G.; Williams, I.; Lombi, L.; Gale, N.K. Women's Experience of Depressive Symptoms While Working From Home During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence From an International Web Survey. Front Sociol 2022, 7, 763088. [CrossRef]

- Damian, A.C.; Ciobanu, A.M.; Anghele, C.; Papacocea, I.R.; Manea, M.C.; Iliuta, F.P.; Ciobanu, C.A.; Papacocea, S. Caregiving for Dementia Patients during the Coronavirus Pandemic. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Zwar, L.; Konig, H.H.; Hajek, A. Gender Differences in Mental Health, Quality of Life, and Caregiver Burden among Informal Caregivers during the Second Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Germany: A Representative, Population-Based Study. Gerontology 2022, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Maggio, M.G.; La Rosa, G.; Calatozzo, P.; Andaloro, A.; Foti Cuzzola, M.; Cannavo, A.; Militi, D.; Manuli, A.; Oddo, V.; Pioggia, G.; et al. How COVID-19 Has Affected Caregivers' Burden of Patients with Dementia: An Exploratory Study Focusing on Coping Strategies and Quality of Life during the Lockdown. J Clin Med 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, S.; Sahu, P.K.; Reed, W.R.; Ganesh, G.S.; Goyal, R.K.; Jain, S. Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on mental health and perceived strain among caregivers tending children with special needs. Res Dev Disabil 2020, 107, 103790. [CrossRef]

- Busse, C.; Barnini, T.; Zucca, M.; Rainero, I.; Mozzetta, S.; Zangrossi, A.; Cagnin, A. Depression, Anxiety and Sleep Alterations in Caregivers of Persons With Dementia After 1-Year of COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 826371. [CrossRef]

- Eckardt, J.P. Caregivers of people with severe mental illness in the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7. [CrossRef]

- Fusar-Poli, L.; Surace, T.; Meo, V.; Patania, F.; Avanzato, C.; Pulvirenti, A.; Aguglia, E.; Signorelli, M.S. Psychological well-being and family distress of Italian caregivers during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Community Psychol 2022, 50, 2243-2259. [CrossRef]

- Stanley, S.; Balakrishnan, S.; Ilangovan, S. Psychological distress, perceived burden and quality of life in caregivers of persons with schizophrenia. J Ment Health 2017, 26, 134-141. [CrossRef]

- Yasuma, N.; Yamaguchi, S.; Ogawa, M.; Shiozawa, T.; Abe, M.; Igarashi, M.; Kawaguchi, T.; Sato, S.; Nishi, D.; Kawakami, N.; et al. Care difficulties and burden during COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns among caregivers of people with schizophrenia: A cross-sectional study. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep 2021, 41, 242-247. [CrossRef]

- Mork, E.; Aminoff, S.R.; Barrett, E.A.; Simonsen, C.; Hegelstad, W.T.V.; Lagerberg, T.V.; Melle, I.; Romm, K.L. COVID-19 lockdown - who cares? The first lockdown from the perspective of relatives of people with severe mental illness. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1104. [CrossRef]

- Jesus, T.S.; Bhattacharjya, S.; Papadimitriou, C.; Bogdanova, Y.; Bentley, J.; Arango-Lasprilla, J.C.; Kamalakannan, S.; The Refugee Empowerment Task Force International Networking Group Of The American Congress Of Rehabilitation, M. Lockdown-Related Disparities Experienced by People with Disabilities during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Scoping Review with Thematic Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [CrossRef]

- Kinser, P.A.; Lyon, D.E. A conceptual framework of stress vulnerability, depression, and health outcomes in women: potential uses in research on complementary therapies for depression. Brain Behav 2014, 4, 665-674. [CrossRef]

- Roncone, R.; Giusti, L.; Mazza, M.; Bianchini, V.; Ussorio, D.; Pollice, R.; Casacchia, M. Persistent fear of aftershocks, impairment of working memory, and acute stress disorder predict post-traumatic stress disorder: 6-month follow-up of help seekers following the L'Aquila earthquake. Springerplus 2013, 2, 636. [CrossRef]

- Casacchia, M.; Bianchini, V.; Mazza, M.; Pollice, R.; Roncone, R. Acute stress reactions and associated factors in the help-seekers after the L'Aquila earthquake. Psychopathology 2013, 46, 120-130. [CrossRef]

- Casacchia, M.; Pollice, R.; Roncone, R. The narrative epidemiology of L'Aquila 2009 earthquake. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2012, 21, 13-21. [CrossRef]

- Cofini, V.; Carbonelli, A.; Cecilia, M.R.; di Orio, F. Quality of life, psychological wellbeing and resilience: a survey on the Italian population living in a new lodging after the earthquake of April 2009. Ann Ig 2014, 26, 46-51. [CrossRef]

- Gigantesco, A.; Mirante, N.; Granchelli, C.; Diodati, G.; Cofini, V.; Mancini, C.; Carbonelli, A.; Tarolla, E.; Minardi, V.; Salmaso, S.; et al. Psychopathological chronic sequelae of the 2009 earthquake in L'Aquila, Italy. J Affect Disord 2013, 148, 265-271. [CrossRef]

- Imperiale, A.J.; Vanclay, F. The mechanism of disaster capitalism and the failure to build community resilience: learning from the 2009 earthquake in L'Aquila, Italy. Disasters 2021, 45, 555-576. [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA 1999, 282, 1737-1744. [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001, 16, 606-613. [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.E.J.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. . Med. Care 1992, 30, 473-483.

- Apolone, G.; Mosconi, P. The Italian SF-36 Health Survey. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 1998, 51, 1025-1036. [CrossRef]

- Roncone, R.; Mazza, M.; Ussorio, D.; Pollice, R.; Falloon, I.R.; Morosini, P.; Casacchia, M. The questionnaire of family functioning: a preliminary validation of a standardized instrument to evaluate psychoeducational family treatments. Community Ment Health J 2007, 43, 591-607. [CrossRef]

- Morosini, P.; Roncone, R.; Veltro, F.; Palomba, U.; Casacchia, M. Routine assessment tool in psychiatry: the case of questionnaire of family attitude and burden Italian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioural Sciences 1991, 1, 95-101.

- Andrews, G.; Hunt, C.; Jarry, M.; Morosini, P.; Roncone, R.; Tibaldi, G. Disturbi mentali. Competenze di base, strumenti e tecniche per tutti gli operatori.; Centro Scientifico Editore: Torino, 2004.

- Roncone, R.; Giusti, L.; Bianchini, V.; Casacchia, M.; Carpiniello, B.; Aguglia, E.; Altamura, M.; Barlati, S.; Bellomo, A.; Bucci, P.; et al. Family functioning and personal growth in Italian caregivers living with a family member affected by schizophrenia: Results of an add-on study of the Italian network for research on psychoses. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1042657. [CrossRef]

- Yazawa, A.; Aida, J.; Kondo, K.; Kawachi, I. Gender differences in risk of posttraumatic stress symptoms after disaster among older people: Differential exposure or differential vulnerability? J Affect Disord 2022, 297, 447-454. [CrossRef]

- Ribe, J.M.; Salamero, M.; Perez-Testor, C.; Mercadal, J.; Aguilera, C.; Cleris, M. Quality of life in family caregivers of schizophrenia patients in Spain: caregiver characteristics, caregiving burden, family functioning, and social and professional support. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2018, 22, 25-33. [CrossRef]

- Barrowclough, C.; Gooding, P.; Hartley, S.; Lee, G.; Lobban, F. Factors associated with distress in relatives of a family member experiencing recent-onset psychosis. J Nerv Ment Dis 2014, 202, 40-46. [CrossRef]

- Ilhan, B.; Berikol, G.B.; Eroglu, O.; Deniz, T. Prevalence and associated risk factors of post-traumatic stress disorder among survivors of the 2023 Turkey earthquake. Am J Emerg Med 2023, 72, 39-43. [CrossRef]

- Pazderka, H.; Shalaby, R.; Eboreime, E.; Mao, W.; Obuobi-Donkor, G.; Agyapong, B.; Oluwasina, F.; Adu, M.K.; Owusu, E.; Sapara, A.; et al. Isolation, Economic Precarity, and Previous Mental Health Issues as Predictors of PTSD Status in Females Living in Fort McMurray During COVID-19. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 837713. [CrossRef]

- Wenham, C.; Smith, J.; Davies, S.E.; Feng, H.; Grepin, K.A.; Harman, S.; Herten-Crabb, A.; Morgan, R. Women are most affected by pandemics - lessons from past outbreaks. Nature 2020, 583, 194-198. [CrossRef]

- Wenham, C.; Smith, J.; Morgan, R.; Gender; Group, C.-W. COVID-19: the gendered impacts of the outbreak. Lancet 2020, 395, 846-848. [CrossRef]

- Bu, F.; Steptoe, A.; Fancourt, D. Loneliness during a strict lockdown: Trajectories and predictors during the COVID-19 pandemic in 38,217 United Kingdom adults. Soc Sci Med 2020, 265, 113521. [CrossRef]

- Purvis, R.S.; Ayers, B.L.; Rowland, B.; Moore, R.; Hallgren, E.; McElfish, P.A. "Life is hard": How the COVID-19 pandemic affected daily stressors of women. Dialogues Health 2022, 1, 100018. [CrossRef]

- Keitner, G.I.; Miller, I.W. Family functioning and major depression: an overview. Am J Psychiatry 1990, 147, 1128-1137. [CrossRef]

- Herr, N.R.; Hammen, C.; Brennan, P.A. Current and past depression as predictors of family functioning: a comparison of men and women in a community sample. J Fam Psychol 2007, 21, 694-702. [CrossRef]

- Febres, J.; Rossi, R.; Gaudiano, B.A.; Miller, I.W. Differential relationship between depression severity and patients' perceived family functioning in women versus in men. J Nerv Ment Dis 2011, 199, 449-453. [CrossRef]

- Fondazione ONDA Osservatorio nazionale sulla salute della donna e di genere. COVID-19 e salute di genere: da pandemia a sindemia. Esperienze, nuove consapevolezze, sfide future. Libro bianco 2021; Franco Angeli: Milano, 2021.

- Arpino, B.; Pasqualini, M. Effects of Pandemic on Feelings of Depression in Italy: The Role of Age, Gender, and Individual Experiences During the First Lockdown. Front Psychol 2021, 12, 660628. [CrossRef]

- Wormald, A.; McGlinchey, E.; D'Eath, M.; Leroi, I.; Lawlor, B.; McCallion, P.; McCarron, M.; O'Sullivan, R.; Chen, Y. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Caregivers of People with an Intellectual Disability, in Comparison to Carers of Those with Other Disabilities and with Mental Health Issues: A Multicountry Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20. [CrossRef]

- Rainero, I.; Bruni, A.C.; Marra, C.; Cagnin, A.; Bonanni, L.; Cupidi, C.; Lagana, V.; Rubino, E.; Vacca, A.; Di Lorenzo, R.; et al. The Impact of COVID-19 Quarantine on Patients With Dementia and Family Caregivers: A Nation-Wide Survey. Front Aging Neurosci 2020, 12, 625781. [CrossRef]

- Boyd, K.; Winslow, V.; Borson, S.; Lindau, S.T.; Makelarski, J.A. Caregiving in a Pandemic: Health-Related Socioeconomic Vulnerabilities Among Women Caregivers Early in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann Fam Med 2022, 20, 406-413. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Chakrabarti, S.; Grover, S. Gender differences in caregiving among family - caregivers of people with mental illnesses. World J Psychiatry 2016, 6, 7-17. [CrossRef]

- Fancourt, D.; Steptoe, A.; Bu, F. Trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms during enforced isolation due to COVID-19 in England: a longitudinal observational study. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 141-149. [CrossRef]

- Holz, N.E.; Berhe, O.; Sacu, S.; Schwarz, E.; Tesarz, J.; Heim, C.M.; Tost, H. Early Social Adversity, Altered Brain Functional Connectivity, and Mental Health. Biol Psychiatry 2023, 93, 430-441. [CrossRef]

| Variables | Working (n=73) |

Not-working (n=138) |

|---|---|---|

| Complex management of family life and work during COVID-19 pandemic (%) |

31 (42.5) |

77 (55.8) |

| Infection with COVID-19 (%) | 9 (12.3) | 12 (8.7) |

| Refusal of COVID-19 vaccination (%) | 6 (8.2) | 10 (7.2) |

| Loss of someone close to COVID-19 (%)* | 7 (9.6) | 21 (15.2) |

| Subjected to the 2009 L'Aquila earthquake (%) (n = 100)* | 45 (61.6) | 55 (39.9) |

| Loss of someone close in the 2009 L'Aquila earthquake (%) (n= 100) | 5 (11.1) | 10 (18.2) |

|

Severe impact of 2009 L'Aquila earthquake on (%) (n = 100 women exposed) (intensity: severe; very severe) |

||

| Family life | 21 (46.7) | 27 (49.1) |

| Work | 18 (40) | 13 (23.6) |

| Social life | 21 (46.7) | 22 (40) |

| Severe impairment due to the L’Aquila 2009 earthquake in two out of the three domains investigated (%) (n=43)* |

22 (30.1) |

21 (15.2) |

| Previous contact due to mental health problems (%) (n = 94) | 38 (52.1) | 56 (40.6) |

| Mental health problems reported (%) | ||

| Anxiety | 20 (27.4) | 40 (29) |

| Family and interpersonal problems | 13 (17.8) | 26 (18.8) |

| Depression | 14 (19.2) | 23 (16.7) |

| Sleep disorders | 9 (12.3) | 15 (10.9) |

| Eating disorders | 10 (13.7) | 12 (8.7) |

| Substance abuse | -- | 3 (2.2) |

| Other problems | 5 (6.8) | 14 (10.1) |

| Treatments | ||

| Admission to a psychiatric ward | -- | 2 (3.5) |

| Psychopharmacological treatment (n=39) | 11 | 28 |

| Type of drug | ||

| Anxiolytic drugs | 4 (36.4) | 8 (28.6) |

| Antidepressant drugs | 6 (54.5) | 14 (50) |

| Antipsychotic drugs | 1 (9.1) | 6 (21.4) |

| Variables | Total Sample (n=211) |

Workers (n=73) |

Non workers (n=138) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 Total mean score (SD)* | 9.5 (6.17) | 7.82 (5.7) | 10.30 (6.2) |

| PHQ-9 Total scoring >10 (%)* | 82 (40.2) | 19 (26) | 63 (45.7) |

| PHQ-9 score 1 - 5 – absent - mild depression (%) | 64 (30.3) | 28 (38.4) | 36 (26.1) |

| PHQ-9 score 6 - 10 – moderate depression (%) | 65 (30.8) | 26 (35.6) | 39 (28.3) |

| PHQ-9 score 11 - 15 - moderately severe depression (%) | 44 (20.9) | 9 (20.5) | 35 (25.4) |

| PHQ-9 score >15 - severe depression (%) | 38 (18) | 10 (26.3) | 28 (20.3) |

| Family Functioning Questionnaire (SD) | |||

| Communication* | 23.3 (4.8) | 24.9 (4.7) | 22.5 (4.6) |

| Problem-Solving* | 21.0 (6.7) | 23.6 (6.0) | 19.7 (6.7) |

| Personal Goals* | 23.8 (3.9) | 22.3 (3.8) | 24.5 (3.8) |

| Variables included | Non-caregivers (n=164) | Caregivers (n=47) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 35.3 (18.5) | 37.0 (18.8) |

| Range age | ||

| Young adults (18 – 35 years) (%) | 100 (61) | 26 (55.3) |

| Adults (%) | 51 (31.1) | 18 (38.3) |

| Over 65 (%) | 13 (7.9) | 3 (6.4) |

| Nationality (%) | ||

| Non-EU citizens | 7 (4.3) | 1 (2.1) |

| Marital status (%) | ||

| Single | 72 (43.9) | 21 (44.7) |

| Married/Partnership | 76 (46.3) | 23 (48.9) |

| Separated/ Divorced | 8 (4.9) | 3 (6.4) |

| Widowed | 8 (4.9) | -- |

| Parents of children (%) | ||

| no | 118 (71.3) | 29 (61.7) |

| 1 child | 15 (9.2) | 8 (17.0) |

| 2 children | 23 (14.1) | 6 (12.7) |

| 3 children | 8 (4.2) | 4 (10.6) |

| Level of education (%) | ||

| >13 years (graduated) | 70 (42.3) | 21 (44.7) |

| Working conditions (%) | ||

| Self-employed/freelancers | 15 (9.1) | 8 (17.0) |

| Full-time work | 32 (19.5) | 3 (6.4) |

| Part-time work | 11 (6.7) | 4 (8.5) |

| Student | 72 (43.9) | 19 (40.4) |

| Housewife | 9 (5.5) | 4 (8.5) |

| Unemployed | 9 (5.5) | 3 (6.4) |

| Retired | 16 (9.8) | 6 (12.8) |

| Socio-economic status (%) | ||

| High-upper middle income | 75 (45.7) | 20 (42.6) |

| Middle-low income | 66 (40.2) | 18 (38.3) |

| Struggling financially | 23 (14.0) | 9 (19.1) |

| Variables | Non-caregivers (n=164) | Caregivers (n=47) |

|---|---|---|

| Complex management of family life and work during COVID-19 pandemic (%) | 86 (52.4) | 22 (46.8) |

| COVID-19 infection (%) | 16 (9.8) | 5 (10.6) |

| Refusal of COVID-19 vaccination (%) | 11 (6.7) | 5 (10.6) |

| Loss of someone close to COVID-19 (%)* | 17 (10.4) | 11 (23.4) |

| Subjected to 2009 L'Aquila earthquake (%) (n = 100) | 77 (47) | 23 (48.9) |

| Loss of someone close in the 2009 L’Aquila earthquake (%) | 12 (15.5) | 3 (13) |

|

Severe impact of 2009 L'Aquila earthquake on (%) (n = 100 women exposed) (intensity: severe; very severe) |

||

| Family life | 37 (48) | 11 (47.8) |

| Work | 25 (32.4) | 6 (26.1) |

| Social life | 32 (41.5) | 11 (47.8) |

| Severe impairment due to the 2009 L'Aquila earthquake in two out of the three domains investigated (%) (n=43) | 33 (42.9) | 10 (43.5) |

| Previous contact due to mental health problems (%) (n = 94) | 71 (43.3) | 23 (48.9) |

| Mental health problems reported (%) | ||

| Anxiety | 42 (25.6) | 18 (38.3) |

| Family and interpersonal problems | 28 (17.1) | 11 (23.4) |

| Depression | 27 (16.5) | 10 (21.3) |

| Sleep disorders | 16 (9.8) | 8 (17) |

| Eating disorders | 17 (10.4) | 5 (10.6) |

| Substance abuse | 1 (0.6) | 2 (4.3) |

| Other problems | 16 (9.8) | 3 (6.4) |

| Treatments | ||

| Admission to a psychiatric ward | 1 | 1 |

| Integrated treatment (drug prescription + psychotherapy) | 14 (8.5) | 7 (14.8) |

| Psychopharmacological treatment (n=39) | 29 | 10 |

| Type of drug | ||

| Anxiolytic drugs | 10 (34.5) | 2 (20) |

| Antidepressant drugs | 16 (55.2) | 4 (40) |

| Antipsychotic drugs | 3 (10.3) | 4 (40) |

| Variables | Non-caregivers (n=164) |

Caregivers (n=47) |

|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 Total mean score (SD) | 9.07 (5.8) | 11 (7.1) |

| PHQ-9 Total scoring >10 (%) | 59 (37.1) | 23 (51.1) |

| PHQ-9 score 1 - 5 – absent - mild depression (%) | 51 (31.1) | 13 (27.7) |

| PHQ-9 score 6 - 10 – moderate depression (%) | 54 (32.9) | 11 (23.4) |

| PHQ-9 score 11 - 15 - moderately severe depression | 35 (21.3) | 9 (19.1) |

| PHQ-9 score >15 - severe depression (%) | 24 (14.6) | 14 (29.8) |

| Family Functioning Questionnaire (SD) | ||

| Communication | 23.5 (4.4) | 22.7 (5.7) |

| Problem-Solving | 21.4 (6.6) | 19.8 (7.1) |

| Personal Goals | 24.0 (3.8) | 23.0 (4.3) |

| Physical Disability Caregivers (n=23) |

Mental Disability Caregivers (n=24) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Family Functioning | ||

| Communication | 22.6 (6.5) | 22.8 (5.1) |

| Problem-Solving | 20.6 (4.3) | 19.0 (6.5) |

| Personal Goals | 22.9 (4.6) | 23.0 (4.1) |

| Burden of care | ||

| Objective burden | 1.79 (0.50) | 1.86 (0.41) |

| Subjective burden* | 2.00 (0.54) | 2.64 (0.70) |

| Support received from professionals | 2.43 (0.92) | 2.51 (0.68) |

| Support received from relatives and friends* | 2.24 (0.98) | 2.80 (0.69) |

| Measures | Age | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pearson’s Correlation | .304** | -- | ||||||||||||

| 2-tailed p-value | .000 | ||||||||||||||

|

Pearson’s Correlation | .245** | .143* | -- | |||||||||||

| 2-tailed p-value | .010 | .038 | |||||||||||||

|

Pearson’s Correlation | .413** | .202** | .512** | -- | ||||||||||

| 2-tailed p-value | .000 | .003 | .000 | ||||||||||||

|

Pearson’s Correlation | .380** | .322** | .451** | .628** | -- | |||||||||

| 2-tailed p-value | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | |||||||||||

|

Pearson’s Correlation | .419** | .204** | .590** | .835** | .646** | -- | ||||||||

| 2-tailed p-value | .000 | .003 | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||||||||||

|

Pearson’s Correlation | .412** | .214** | .542** | .755** | .611** | .697** | -- | |||||||

| 2-tailed p-value | .001 | .002 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | |||||||||

|

Pearson’s Correlation | -.452** | -.310** | -.560** | -.836** | -.681** | -.799** | -.738** | -- | ||||||

| 2-tailed p-value | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||||||||

|

Pearson’s Correlation | -.171 | -.151 | -.384** | -.207 | -.354* | -.337* | -.300* | .332* | -- | |||||

| 2-tailed p-value | .249 | .312 | .008 | .162 | .015 | .020 | .040 | .023 | |||||||

|

Pearson’s Correlation | -.076 | -.011 | -.292* | -.545** | -.391** | -.631** | -.550** | .501** | .563** | -- | ||||

| 2-tailed p-value | .612 | .940 | .047 | .000 | .007 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||||||

|

Pearson’s Correlation | .020 | -.179 | -.207 | -.342* | -.155 | -.412** | -.231 | .303* | .232 | .304* | -- | |||

| 2-tailed p-value | .892 | .228 | .163 | .019 | .298 | .004 | .118 | .039 | .116 | .038 | |||||

|

Pearson’s Correlation | -.031 | -.186 | -.236 | -.200 | -.139 | -.336* | -.199 | .301* | .007 | .155 | .580** | -- | ||

| 2-tailed p-value | .836 | .211 | .111 | .178 | .352 | .021 | .179 | .040 | .962 | .299 | .000 | ||||

|

Pearson’s Correlation | .434** | .291** | .422** | .519** | .399* | .556** | .529** | -.569** | -.130 | -.110 | -.465** | -.453** | -- | |

| 2-tailed p-value | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .010 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .385 | .462 | .001 | .001 | |||

|

Pearson’s Correlation | .382** | .214** | .404** | .442** | .324** | .460** | .433** | -.472** | -.290* | -.291* | -.373** | -.309* | .733** | -- |

| 2-tailed p-value | .000 | .002 | .000 | .000 | .002 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .048 | .047 | .010 | .034 | .000 | ||

|

Pearson’s Correlation | -.147* | -.167* | .350** | .208** | .131 | .233** | .277** | -.209** | -.261 | -.300* | -.403** | -.315* | .171* | .165* |

| 2-tailed p-value | .032 | .015 | .000 | .002 | .058 | .001 | .000 | .002 | .076 | .041 | .005 | .031 | .013 | .016 | |

| Variables | B | Standard error | Wald | df | p | Exp(B) | 95% confidence interval for Exp(B) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||||||

| Moderate depression (PHQ-9 = scoring 2) |

Intercepts | 7.611 | 2.175 | 12.244 | 1 | .000 | |||

| Age | -.036 | .014 | 6.719 | 1 | .010 | .964 | .938 | .991 | |

| Lack of a stable romantic partnership | .124 | .454 | .075 | 1 | .784 | 1.132 | .465 | 2.756 | |

| Less than 13 years of education | .362 | .441 | .675 | 1 | .411 | 1.436 | .605 | 3.408 | |

| Struggling financially | -.427 | .770 | .307 | 1 | .579 | .652 | .144 | 2.952 | |

| Previous access to mental health services | .634 | .446 | 2.022 | 1 | .155 | 1.885 | .787 | 4.514 | |

| Traumatic experience with the 2009 L’Aquila earthquake | 1.369 | .552 | 6.142 | 1 | .013 | 3.932 | 1.332 | 11.612 | |

| COVID-19 infection | .239 | .724 | .109 | 1 | .742 | 1.270 | .307 | 5.248 | |

| Complex life management during the COVID-19 pandemic | .533 | .435 | 1.501 | 1 | .221 | 1.705 | .726 | 4.003 | |

| Caregiving for a loved one | -.129 | .571 | .051 | 1 | .821 | .879 | .287 | 2.693 | |

| Problem-solving | -.093 | .056 | 2.768 | 1 | .096 | .912 | .817 | 1.017 | |

| Communication | -.095 | .073 | 1.700 | 1 | .192 | .909 | .788 | 1.049 | |

| Personal goals | -.100 | .061 | 2.708 | 1 | .100 | .905 | .803 | 1.019 | |

| Moderately severe depression (PHQ-9 = scoring 3) |

Intercepts | 7.688 | 2.659 | 8.362 | 1 | .004 | |||

| Age | -.095 | .024 | 16.332 | 1 | .000 | .909 | .868 | .952 | |

| Lack of a stable romantic partnership | 1.101 | .568 | 3.759 | 1 | .053 | 3.006 | .988 | 9.148 | |

| Less than 13 years of education | .306 | .570 | .289 | 1 | .591 | 1.358 | .444 | 4.152 | |

| Struggling financially | .870 | .773 | 1.269 | 1 | .260 | 2.387 | .525 | 10.852 | |

| Previous access to mental health services | 1.956 | .576 | 11.548 | 1 | .001 | 7.070 | 2.288 | 21.842 | |

| Traumatic experience with the 2009 L’Aquila earthquake | 2.242 | .771 | 8.454 | 1 | .004 | 9.416 | 2.077 | 42.691 | |

| COVID-19 infection | -.073 | .955 | .006 | 1 | .939 | .930 | .143 | 6.039 | |

| Complex life management during the COVID-19 pandemic | 1.086 | .545 | 3.970 | 1 | .046 | 2.964 | 1.018 | 8.628 | |

| Caregiving for a loved one | .304 | .674 | .203 | 1 | .652 | 1.355 | .362 | 5.075 | |

| Problem-solving | -.164 | .063 | 6.666 | 1 | .010 | .849 | .750 | .961 | |

| Communication | -.029 | .084 | .123 | 1 | .726 | .971 | .824 | 1.145 | |

| Personal goals | -.127 | .078 | 2.628 | 1 | .105 | .881 | .756 | 1.027 | |

| Severe depression (PHQ-9 = scoring 4). |

Intercepts | 10.578 | 2.888 | 13.412 | 1 | .000 | |||

| Age | -.068 | .026 | 6.944 | 1 | .008 | .934 | .888 | .983 | |

| Lack of a stable romantic partnership | 1.113 | .674 | 2.730 | 1 | .098 | 3.044 | .813 | 11.399 | |

| Less than 13 years of education | 1.688 | .732 | 5.318 | 1 | .021 | 5.410 | 1.288 | 22.714 | |

| Struggling financially | 1.224 | .841 | 2.119 | 1 | .145 | 3.402 | .654 | 17.687 | |

| Previous access to mental health services | 2.391 | .675 | 12.541 | 1 | .000 | 10.923 | 2.908 | 41.020 | |

| Traumatic experience with the 2009 L’Aquila earthquake | 1.705 | .966 | 3.117 | 1 | .077 | 5.502 | .829 | 36.527 | |

| COVID-19 infection | -.483 | 1.068 | .204 | 1 | .651 | .617 | .076 | 5.008 | |

| Complex life management during the COVID-19 pandemic | 1.280 | .640 | 4.001 | 1 | .045 | 3.598 | 1.026 | 12.616 | |

| Caregiving for a loved one | 1.058 | .734 | 2.076 | 1 | .150 | 2.880 | .683 | 12.147 | |

| Problem-solving | -.234 | .073 | 10.438 | 1 | .001 | .791 | .686 | .912 | |

| Communication | -.124 | .095 | 1.725 | 1 | .189 | .883 | .734 | 1.063 | |

| Personal goals | -.222 | .088 | 6.368 | 1 | .012 | .801 | .674 | .952 | |

|

a. The reference category is 1. PHQ-9 absent / mild depression total score: 0-5 In bold: statistically significant values | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).