Submitted:

27 September 2023

Posted:

28 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

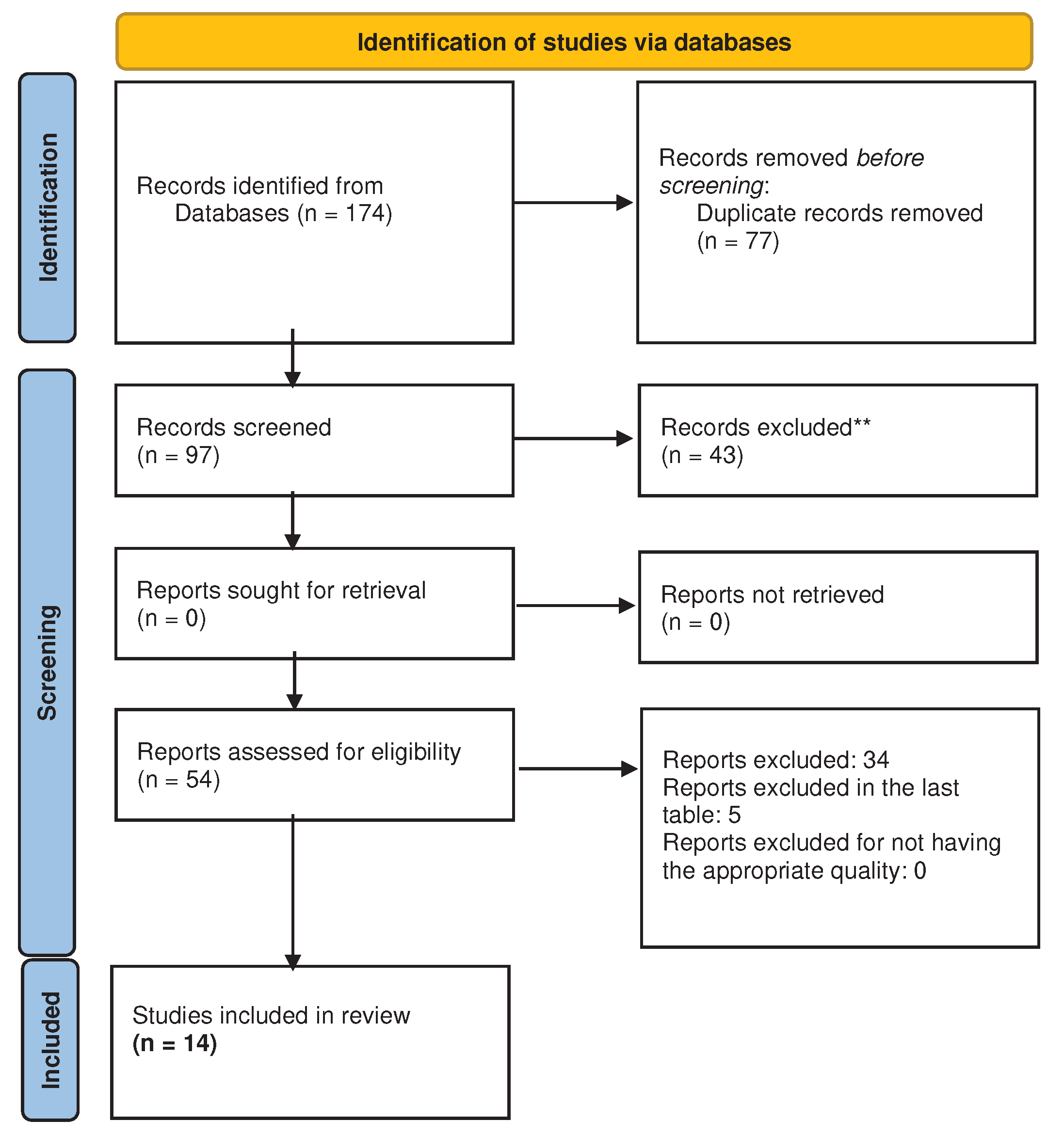

2. Materials and Methods

Study design

Eligibility criteria

- Studies with samples of adult women from both clinical and non-clinical contexts.

- Studies that evaluated sexual health and mental health or PWB variables.

- Studies that associated sexual health and mental health or PWB variables.

Information source

Search strategies

Data collection process

Data items

Study risk of bias assessment

Synthesis methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ryff, CD. Eudaimonic well-being: Highlights from 25 years of inquiry. In K. Shigemasu K, Kuwano S, Sato T, Matsuzawa T, Eds.; Diversity in harmony-insights from psychology: Proceedings of the 31st International Congress of Psychology.; Diversity in harmony-insights from psychology: Proceedings of the 31st International Congress of Psychology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 2018; pp. 2018375–395. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, CD. Psychological well-being revisited: Advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychother Psychosom. 2014, 83, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (2006). Defining sexual health: Report of a technical consultation on sexual health, , Geneva. Retrieved from https://www3.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=2136:2009-defining-sexual-health&Itemid=0&lang=es#gsc.tab=0. 28–31 January.

- Laurent SM, Simons AD. Sexual dysfunction in depression and anxiety: Conceptualizing sexual dysfunction as part of an internalizing dimension. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009, 29, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O’Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007, 357, 762–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehbein-Narvaez R, García-Vázquez E, Madson L. The relation between self-esteem and sexual functioning in collegiate women. J Soc Psychol. 2006, 146, 250–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woloski-Wruble AC, Oliel Y, Leefsma M, Hochner-Celnikier D. Sexual activities, sexual and life satisfaction, and successful aging in women. J Sex Med. 2010, 7, 2401–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison SL, Bell RJ, LaChina M, Holden SL, Davis SR. The relationship between self-reported sexual satisfaction and general well-being in women. J Sex Med. 2009, 6, 2690–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCool-Myers M, Theurich M, Zuelke A, Knuettel H, Apfelbacher C. Predictors of female sexual dysfunction: a systematic review and qualitative analysis through gender inequality paradigms. BMC Womens Health. 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West SL, Vinikoor LC, Zolnoun D. A systematic review of the literature on female sexual dysfunction prevalence and predictors. Annual review of sex research. 2004, 15, 40–172. [Google Scholar]

- Basson R, Berman J, Burnett A, Derogatis L, Ferguson D, Fourcroy J, et al. Report of the international consensus development conference on female sexual dysfunction: Definitions and classifications. J Sex Marital Ther. 2001, 27, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enzlin P, Mathieu C, Van den Bruel A, Vanderschueren D, Demyttenaere K. Prevalence and predictors of sexual dysfunction in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003, 26, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devkota L, Pant SB, Ojha SP, Chapagai M. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction in women with depressive disorder at a tertiary hospital. J Psychosexual Health. 2022, 4, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: Prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999, 281, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kılıç, M. Prevalence and risk factors of sexual dysfunction in healthy women in Turkey. Afr Health Sci. 2019, 19, 2623–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du J, Ruan X, Gu M, Bitzer J, Mueck AO. Prevalence of and risk factors for sexual dysfunction in young Chinese women according to the Female Sexual Function Index: an internet-based survey. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2016, 21, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolpe RE, Zomkowski K, Silva FP, Queiroz APA, Sperandio FF. Prevalence of female sexual dysfunction in Brazil: A systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017, 211, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blümel JE, Chedraui P, Baron G, Belzares E, Bencosme A, Calle A, et al. Sexual dysfunction in middle-aged women: A multicenter Latin American study using the Female Sexual Function Index. Menopause. 2009, 16, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie H, Dewey A, Drahota A, Kilburn S, Kalra P, Fogg C, Zachariah D. Systematic reviews: what they are, why they are important, and how to get involved. J Clin Prev Cardiol. 2012, 1, 193–202. [Google Scholar]

- Strech D, Sofaer N. How to write a systematic review of reasons. J Med Ethics. 2012, 38, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo A, Capela E, Peixoto M. Sexual satisfaction among lesbian and heterosexual cisgender women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare (Basel). 2023, 11, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthew, J. Page, Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, Roger Chou, Julie Glanville, Jeremy M. Grimshaw, Asbjørn Hróbjartsson, Manoj M. Lalu, Tianjing Li, Elizabeth W. Loder, Evan Mayo-Wilson, Steve McDonald, Luke A. McGuinness, Lesley A. Stewart, James Thomas, Andrea C. Tricco, Vivian A. Welch, Penny Whiting, David Moher, Juan José Yepes-Nuñez, Gerard Urrútia, Marta Romero-García, Sergio Alonso-Fernández. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2021, 74, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Study Quality Assessment Tools. 2013. Retrieved from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools.

- *Dong M, Wu S, Tao Y, Zhou F, Tan J. The impact of postponed fertility treatment on the sexual health of infertile patients owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Med. 2021, 8, 730994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Fogh M, Højgaard A, Rotbøl CB, Jensen AB. The majority of Danish breast cancer survivors on adjuvant endocrine therapy have clinically relevant sexual dysfunction: A cross-sectional study. Acta Oncol. 2021, 60, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Liñan-Bermudez A, Chafloque-Chavesta J, Pastuso PL, Pinedo KH, Barja-Ore J. Severity of climacteric symptomatology related to depression and sexual function in women from a private clinic. Prz Menopauzalny. 2022, 21, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Mistler CB, Sullivan MC, Copenhaver MM, Meyer JP, Roth AM, Shenoi SV, Edelman EJ, Wickersham JA, Shrestha R. Differential impacts of COVID-19 across racial-ethnic identities in persons with opioid use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021, 129, 108387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Philip EJ, Nelson C, Temple L, Carter J, Schover L, Jennings S, Jandorf L, Starr T, Baser R, DuHamel K. Psychological correlates of sexual dysfunction in female rectal and anal cancer survivors: Analysis of baseline intervention data. J Sex Med. 2013, 10, 2539–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Simon JA, Athavale A, Ravindranath R, Hadker N, Sadiq A, Lim-Watson M, Williams L, Krop J. Assessing the burden of illness associated with acquired generalized hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Womens Health. 2022, 31, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Dubin JM, Wyant WA, Balaji NC, Efimenko IV, Rainer QC, Mora B, Paz L, Winter AG, Ramasamy R. Is female wellness affected when men blame them for erectile dysfunction? Sex Med. 2021, 9, 100352. [CrossRef]

- *Mollaioli D, Sansone A, Ciocca G, Limoncin E, Colonnello E, Di Lorenzo G, Jannini EA. Benefits of sexual activity on psychological, relational, and sexual health during the COVID-19 breakout. J Sex Med. 2021, 18, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Polihronakis CJ, Velez BL, Watson LB. Bisexual women's sexual health: A test of objectification theory. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2023, 10, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Vedovo F, Di Blas L, Aretusi F, Falcone M, Perin C, Pavan N, Rizzo M, Morelli G, Cocci A, Polito C, Gentile G, Colombo F, Timpano M, Verze P, Imbimbo C, Bettocchi C, Pascolo Fabrici E, Palmieri A, Trombetta C. Physical, mental and sexual health among transgender women: A comparative study among operated transgender and cisgender women in a national tertiary referral network. J Sex Med. 2021, 18, 982–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Vedovo F, Capogrosso P, Di Blas L, Cai T, Arcaniolo D, Privitera S, Palumbo F, Palmieri A, Trombetta C. Longitudinal impact of social restrictions on sexual health in the Italian population. J Sex Med. 2022, 19, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Cook SC, Valente AM, Maul TM, Dew MA, Hickey J, Jennifer Burger P, Harmon A, Clair M, Webster G, Cecchin F, Khairy P, Alliance for Adult Research in Congenital Cardiology. Shock-related anxiety and sexual function in adults with congenital heart disease and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Heart Rhythm. 2013, 10, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Hertz PG, Turner D, Barra S, Biedermann L, Retz-Junginger P, Schöttle D, Retz W. Sexuality in adults with ADHD: Results of an online survey. Front Psychiatry. 2022, 13, 868278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Mooney KM, Poirier É, Pukall CF. Persistent genital arousal in relationships: A comparison of relationship, sexual, and psychological well-being. J Sex Med. 2022, 19, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford J, Finch JF, Woodrow LK, Cutitta KE, Shea J, Fischer A, Hazelton G, Sears SF. The Florida Shock Anxiety Scale (FSAS) for patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators: Testing factor structure, reliability, and validity of a previously established measure. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2012, 35, 1146–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, Brähler E, Schellberg D, Herzog W, Herzberg PY. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008, 46, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961, 4, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Corporation Ed.; USA, 1996.

- Beck AT, Guth D, Steer RA, Ball R. Screening for major depression disorders in medical inpatients with the Beck Depression Inventory for Primary Care. Behav Res Ther. 1997, 35, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derogatis, LR. Brief Symptom Inventory; Clinical Psychometric Research; USA, 1975.

- Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, Ferguson D, D'Agostino R Jr. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000, 26, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedovo F, Di Blas L, Perin C, Pavan N, Zatta M, Bucci S, Morelli G, Cocci A, Delle Rose A, Caroassai Grisanti S, Gentile G, Colombo F, Rolle L, Timpano M, Verze P, Spirito L, Schiralli F, Bettocchi C, Garaffa G, Palmieri A, Mirone V, Trombetta C. Operated Male-to-Female Sexual Function Index: Validity of the first questionnaire developed to assess sexual function after male-to-female gender affirming surgery. J Urol. 2020, 204, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sánchez F, Ferrer-Casanova C, Ponce-Buj B, Sipán-Sarrión Y, Jurado-López AR, San Martin-Blanco C, Tijeras-Úbeda MJ, Ferrández Infante A. Diseño y validación de la segunda edición del Cuestionario de Función Sexual de la Mujer, FSM-2. Med Fam Semergen. 2020, 46, 324–330. [CrossRef]

- Lawrance K, Byers ES, Cohen JN. Interpersonal Exchange Model of Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire. In Handbook of sexuality-related measures, 3rd ed.; Fisher TD, Davis CM, Yarber WL, Davis SL, Eds.; Routledge; USA, 2011, pp. 525–30.

- Joyce CR, Zutshi DW, Hrubes V, Mason RM. Comparison of fixed interval and visual analogue scales for rating chronic pain. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1975, 8, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Iglesias, P. , Mohamed, B., Danko, A., Walker LM. Psychometric validation of the female sexual distress scale in male samples. Arch Sex Behav. 2018, 47, 1733–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giraldi A, Rellini A, Pfaus JG, Bitzer, J, Laan, E, Jannini EA, Fugl-Meyer, AR. Questionnaires for Assessment of female sexual dysfunction: A review and proposal for a standardized screener. J Sex Med. 2011, 8, 2681–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchik JA, Garske JP. Measurement of sexual risk taking among college students. Arch Sex Behav. 2009, 38, 936–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozee HB, Tylka TL, Augustus-Horvath CL, Denchik A. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Interpersonal Sexual Objectification Scale. Psychol Women Q. 2007, 31, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra JC, Vallejo-Medina P, Santos-Iglesias P, Lameiras Fernández M. Validación del Massachusetts General Hospital-Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (MGH-SFQ) en población española. Aten Primaria. 2012, 44, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Fuentes MD, Moyano N, Granados R, Sierra Freire JC. Validation of the Spanish version of the Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX) using self-reported and psychophysiological measures.

- Juhari JA, Gill JS, Francis B. Coping strategies and mental disorders among the LGBT+ community in Malaysia. Healthcare (Basel). 2022, 10, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlik BD, Kolzet JA, Ahmad N, Parveen T, Alvi S. Female Sexual Health. In Principles of Gender-Specific Medicine, 2nd ed.; Legato, M. J., Ed.; USA, 2010, pp. 400–407.

- Rezaei N, Taheri S, Tavalaee Z, Rezaie S, Azadi A. The effect of sexual health education program on sexual function and attitude in women at reproductive age in Iran. J Educ Health Promot. 2021, 10, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahnaz, E. , Nasim, B., Sonia, O. Effect of a structured educational package on women's sexual function during pregnancy. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2020, 148, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).