Submitted:

18 January 2024

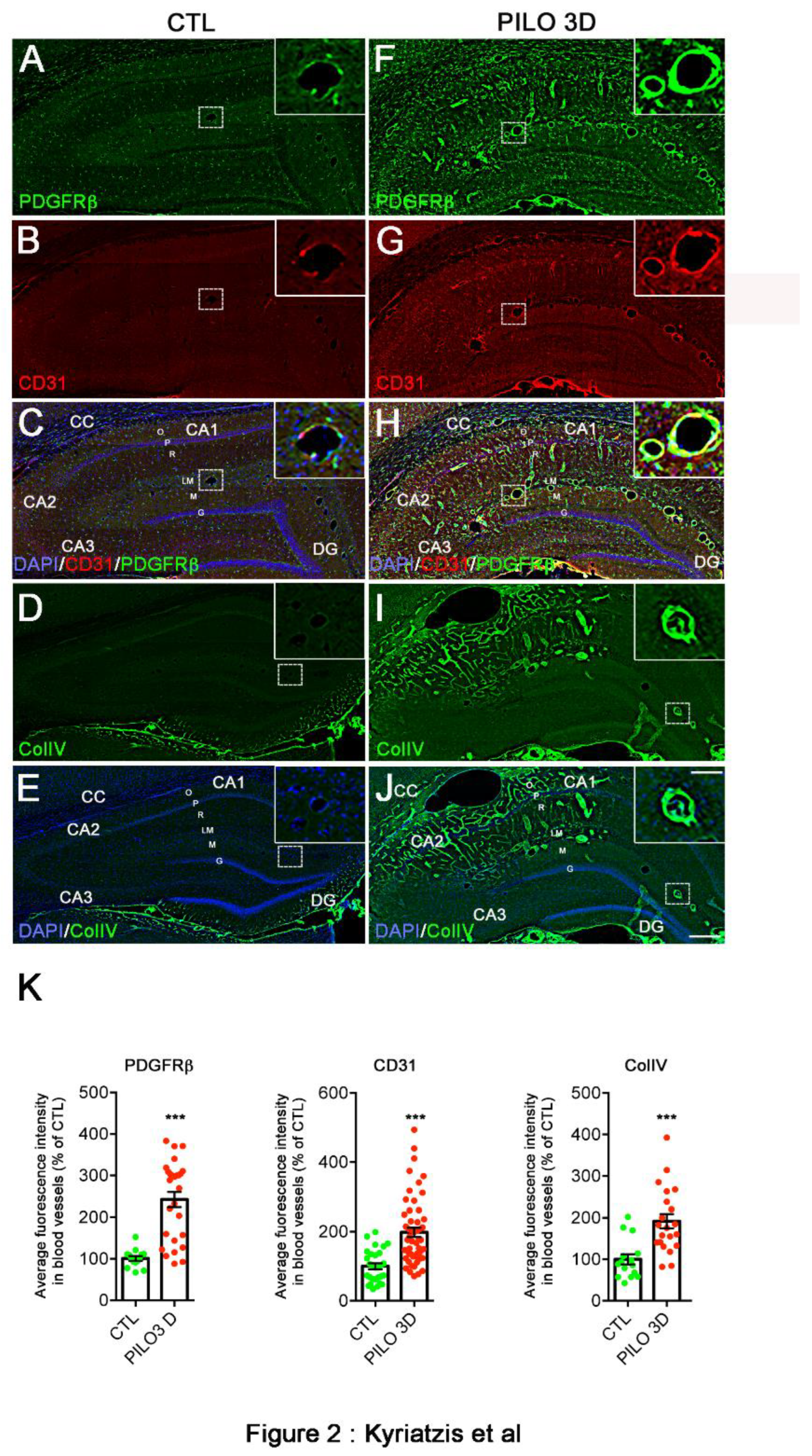

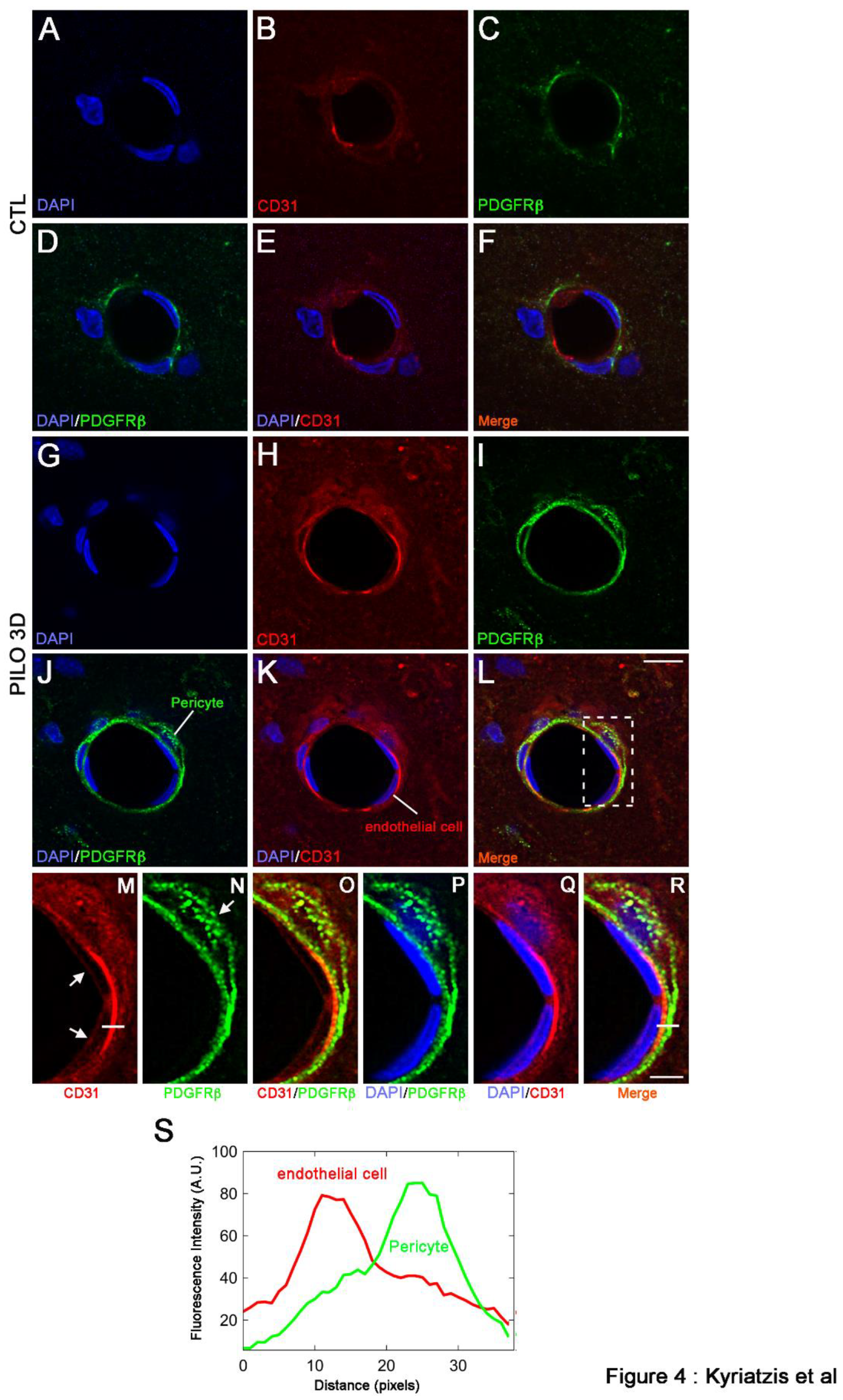

Posted:

18 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethics Statement

4.2. Rat pilocarpine TLE model

4.3. RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

4.4. Tissue preparation for immunohistochemistry

4.5. Immunohistochemistry

4.6. Confocal microscopy and quantification

4.7. Statistical analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baulac, M.; de Boer, H.; Elger, C.; Glynn, M.; Kälviäinen, R.; Little, A.; Mifsud, J.; Perucca, E.; Pitkänen, A.; Ryvlin, P. Epilepsy Priorities in Europe: A Report of the ILAE-IBE Epilepsy Advocacy Europe Task Force. Epilepsia 2015, 56, 1687–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayalew, M.B.; Muche, E.A. Patient Reported Adverse Events among Epileptic Patients Taking Antiepileptic Drugs. SAGE Open Med. 2018, 6, 2050312118772471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferhat, L. Potential Role of Drebrin a, an f-Actin Binding Protein, in Reactive Synaptic Plasticity after Pilocarpine-Induced Seizures: Functional Implications in Epilepsy. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 2012, 474351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, D.S.; Kuruba, R. Experimental Models of Status Epilepticus and Neuronal Injury for Evaluation of Therapeutic Interventions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 18284–18318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curia, G.; Lucchi, C.; Vinet, J.; Gualtieri, F.; Marinelli, C.; Torsello, A.; Costantino, L.; Biagini, G. Pathophysiogenesis of Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy: Is Prevention of Damage Antiepileptogenic? Curr. Med. Chem. 2014, 21, 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissberg, I.; Reichert, A.; Heinemann, U.; Friedman, A. Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction in Epileptogenesis of the Temporal Lobe. Epilepsy Res Treat. 2011, 143908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, N.J.; Patabendige, A.A.K.; Dolman, D.E.M.; Yusof, S.R.; Begley, D.J. Structure and Function of the Blood-Brain Barrier. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010, 37, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Privratsky, J.R.; Newman, D.K.; Newman, P.J. PECAM-1: Conflicts of Interest in Inflammation. Life Sci. 2010, 87, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miettinen, M.; Lindenmayer, A.E.; Chaubal, A. Endothelial Cell Markers CD31, CD34, and BNH9 Antibody to H- and Y-Antigens--Evaluation of Their Specificity and Sensitivity in the Diagnosis of Vascular Tumors and Comparison with von Willebrand Factor. Mod. Pathol. 1994, 7, 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Mbagwu, S.I.; Filgueira, L. Differential Expression of CD31 and Von Willebrand Factor on Endothelial Cells in Different Regions of the Human Brain: Potential Implications for Cerebral Malaria Pathogenesis. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, G.; Takata, F.; Kataoka, Y.; Kanou, K.; Morichi, S.; Dohgu, S.; Kawashima, H. The Neuroinflammatory Role of Pericytes in Epilepsy. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, E.A.; Bell, R.D.; Zlokovic, B.V. Central Nervous System Pericytes in Health and Disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2011, 14, 1398–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armulik, A.; Genové, G.; Mäe, M.; Nisancioglu, M.H.; Wallgard, E.; Niaudet, C.; He, L.; Norlin, J.; Lindblom, P.; Strittmatter, K.; et al. Pericytes Regulate the Blood-Brain Barrier. Nature 2010, 468, 557–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, D.O.; Kim, H.; Holl, D.; Werne Solnestam, B.; Lundeberg, J.; Carlén, M.; Göritz, C.; Frisén, J. Reducing Pericyte-Derived Scarring Promotes Recovery after Spinal Cord Injury. Cell 2018, 173, 153–165.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klement, W.; Blaquiere, M.; Zub, E.; deBock, F.; Boux, F.; Barbier, E.; Audinat, E.; Lerner-Natoli, M.; Marchi, N. A Pericyte-Glia Scarring Develops at the Leaky Capillaries in the Hippocampus during Seizure Activity. Epilepsia 2019, 60, 1399–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.; Liu, F.; Xu, W.; Liu, J.; Chen, S.; Wu, G. Transplanting GABAergic Neurons Differentiated from Neural Stem Cells into Hippocampus Inhibits Seizures and Epileptiform Discharges in Pilocarpine-Induced Temporal Lobe Epilepsy Model. World Neurosurg. 2019, 128, e1–e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, P.; Dingledine, R.; Aronica, E.; Bernard, C.; Blümcke, I.; Boison, D.; Brodie, M.J.; Brooks-Kayal, A.R.; Engel, J.; Forcelli, P.A.; et al. Commonalities in Epileptogenic Processes from Different Acute Brain Insults: Do They Translate? Epilepsia 2018, 59, 37–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Vliet, E.A.; Otte, W.M.; Gorter, J.A.; Dijkhuizen, R.M.; Wadman, W.J. Longitudinal Assessment of Blood-Brain Barrier Leakage during Epileptogenesis in Rats. A Quantitative MRI Study. Neurobiol. Dis. 2014, 63, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorter, J.A.; van Vliet, E.A.; Aronica, E. Status Epilepticus, Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption, Inflammation, and Epileptogenesis. Epilepsy Behav. 2015, 49, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroso, M.; Balosso, S.; Ravizza, T.; Liu, J.; Aronica, E.; Iyer, A.M.; Rossetti, C.; Molteni, M.; Casalgrandi, M.; Manfredi, A.A.; et al. Toll-like Receptor 4 and High-Mobility Group Box-1 Are Involved in Ictogenesis and Can Be Targeted to Reduce Seizures. Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebner, S.; Dijkhuizen, R.M.; Reiss, Y.; Plate, K.H.; Agalliu, D.; Constantin, G. Functional Morphology of the Blood-Brain Barrier in Health and Disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 135, 311–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Vliet, E.A.; da Costa Araújo, S.; Redeker, S.; van Schaik, R.; Aronica, E.; Gorter, J.A. Blood-Brain Barrier Leakage May Lead to Progression of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Brain J. Neurol. 2007, 130, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomkins, O.; Shelef, I.; Kaizerman, I.; Eliushin, A.; Afawi, Z.; Misk, A.; Gidon, M.; Cohen, A.; Zumsteg, D.; Friedman, A. Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption in Post-Traumatic Epilepsy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2008, 79, 774–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raabe, A.; Schmitz, A.K.; Pernhorst, K.; Grote, A.; von der Brelie, C.; Urbach, H.; Friedman, A.; Becker, A.J.; Elger, C.E.; Niehusmann, P. Cliniconeuropathologic Correlations Show Astroglial Albumin Storage as a Common Factor in Epileptogenic Vascular Lesions. Epilepsia 2012, 53, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, D.C.; Tewari, B.P.; Chaunsali, L.; Sontheimer, H. Neuron-Glia Interactions in the Pathophysiology of Epilepsy. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 20, 282–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Pristov, J.B.; Nobili, P.; Nikolić, L. Can Glial Cells Save Neurons in Epilepsy? Neural Regen. Res. 2023, 18, 1417–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyriatzis, G.; Bernard, A.; Bôle, A.; Pflieger, G.; Chalas, P.; Masse, M.; Lécorché, P.; Jacquot, G.; Ferhat, L.; Khrestchatisky, M. Neurotensin Receptor 2 Is Induced in Astrocytes and Brain Endothelial Cells in Relation to Neuroinflammation Following Pilocarpine-Induced Seizures in Rats. Glia 2021, 69, 2618–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt-Kastner, R.; Ingvar, M. Loss of Immunoreactivity for Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP) in Astrocytes as a Marker for Profound Tissue Damage in Substantia Nigra and Basal Cortical Areas after Status Epilepticus Induced by Pilocarpine in Rat. Glia 1994, 12, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.K.; Reams, R.Y.; Jordan, W.H.; Miller, M.A.; Thacker, H.L.; Snyder, P.W. Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy: Pathogenesis, Induced Rodent Models and Lesions. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007, 35, 984–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knake, S.; Hamer, H.M.; Rosenow, F. Status Epilepticus: A Critical Review. Epilepsy Behav. 2009, 15, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, I.E.; Gabriel, S.; Fetani, A.F.; Kann, O.; Heinemann, U. Redistribution of Astrocytic Glutamine Synthetase in the Hippocampus of Chronic Epileptic Rats. Glia 2011, 59, 1706–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzunalli, G.; Dieterly, A.M.; Kemet, C.M.; Weng, H.-Y.; Soepriatna, A.H.; Goergen, C.J.; Shinde, A.B.; Wendt, M.K.; Lyle, L.T. Dynamic Transition of the Blood-Brain Barrier in the Development of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Brain Metastases. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 6334–6348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, N.F.; Pansani, A.P.; Carmanhães, E.R.F.; Tange, P.; Meireles, J.V.; Ochikubo, M.; Chagas, J.R.; da Silva, A.V.; Monteiro de Castro, G.; Le Sueur-Maluf, L. The Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown During Acute Phase of the Pilocarpine Model of Epilepsy Is Dynamic and Time-Dependent. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, M.; Li, L.; Zhang, W. Pericytes for Therapeutic Approaches to Ischemic Stroke. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 629297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt-Kastner, R.; Ingvar, M. Laminar Damage of Neurons and Astrocytes in Neocortex and Hippocampus of Rat after Long-Lasting Status Epilepticus Induced by Pilocarpine. Epilepsy Res. Suppl. 1996, 12, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Massey, C.A.; Sowers, L.P.; Dlouhy, B.J.; Richerson, G.B. Mechanisms of Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy: The Pathway to Prevention. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2014, 10, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teran, F.A.; Bravo, E.; Richerson, G.B. Chapter 8 - Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy: Respiratory Mechanisms. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Chen, R., Guyenet, P.G., Eds.; Respiratory Neurobiology: Physiology and Clinical Disorders, Part II; Elsevier, 2022; Vol. 189, pp. 153–176. [CrossRef]

- Olesen, J.B.; Abildstrøm, S.Z.; Erdal, J.; Gislason, G.H.; Weeke, P.; Andersson, C.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Hansen, P.R. Effects of Epilepsy and Selected Antiepileptic Drugs on Risk of Myocardial Infarction, Stroke, and Death in Patients with or without Previous Stroke: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2011, 20, 964–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, E.M.; Fulford, R.A. Pilocarpine-Induced Convulsions and Delayed Psychotic-like Reaction. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1961, 39, 1287–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouchi, H.; Ogier, M.; Dieuset, G.; Morales, A.; Georges, B.; Rouanet, J.-L.; Martin, B.; Ryvlin, P.; Rheims, S.; Bezin, L. Respiratory Dysfunction in Two Rodent Models of Chronic Epilepsy and Acute Seizures and Its Link with the Brainstem Serotonin System. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbai, O.; Soussi, R.; Bole, A.; Khrestchatisky, M.; Esclapez, M.; Ferhat, L. The Actin Binding Protein α-Actinin-2 Expression Is Associated with Dendritic Spine Plasticity and Migrating Granule Cells in the Rat Dentate Gyrus Following Pilocarpine-Induced Seizures. Exp. Neurol. 2021, 335, 113512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esclapez, M.; Hirsch, J.C.; Ben-Ari, Y.; Bernard, C. Newly Formed Excitatory Pathways Provide a Substrate for Hyperexcitability in Experimental Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. J. Comp. Neurol. 1999, 408, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffin, K.; Nissinen, J.; Van Laere, K.; Pitkänen, A. Cyclicity of Spontaneous Recurrent Seizures in Pilocarpine Model of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy in Rat. Exp. Neurol. 2007, 205, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garzillo, C.; Mello, L. Characterization of Reactive Astrocytes in the Chronic Phase of the Pilocarpine Model of Epilepsy. Epilepsia 2002, 43, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Koh, S. Role of Brain Inflammation in Epileptogenesis. Yonsei Med. J. 2008, 49, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, L.A.; Wang, L.; Ribak, C.E. Rapid Astrocyte and Microglial Activation Following Pilocarpine-Induced Seizures in Rats. Epilepsia 2008, 49 Suppl 2, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertkiatmongkol, P.; Liao, D.; Mei, H.; Hu, Y.; Newman, P.J. Endothelial Functions of Platelet/Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 (CD31). Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2016, 23, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, B.C.; Xu, P.; Gao, M.; Wang, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhu, X.; Won, M.-H.; Su, P.Q. Changes in the Blood-Brain Barrier Function Are Associated With Hippocampal Neuron Death in a Kainic Acid Mouse Model of Epilepsy. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.; Musto, A.E. The Role of Inflammation in the Development of Epilepsy. J. Neuroinflammation 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, K.C.; Zhao, R.W.; Ueno, K.; Hickey, W.F. PECAM-1 (CD31) Expression in the Central Nervous System and Its Role in Experimental Allergic Encephalomyelitis in the Rat. J. Neurosci. Res. 1996, 45, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.; Ma, L.; Wang, G.; Coe, D.; Ferro, R.; Falasca, M.; Buckley, C.D.; Mauro, C.; Marelli-Berg, F.M. CD31 Signals Confer Immune Privilege to the Vascular Endothelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112, E5815–5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Ishii, Y.; Xu, G.; Dang, T.C.; Hamashima, T.; Matsushima, T.; Yamamoto, S.; Hattori, Y.; Takatsuru, Y.; Nabekura, J.; et al. PDGFR-β as a Positive Regulator of Tissue Repair in a Mouse Model of Focal Cerebral Ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2012, 32, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iihara, K.; Sasahara, M.; Hashimoto, N.; Hazama, F. Induction of Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Beta-Receptor in Focal Ischemia of Rat Brain. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1996, 16, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krupinski, J.; Issa, R.; Bujny, T.; Slevin, M.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, S.; Kaluza, J. A Putative Role for Platelet-Derived Growth Factor in Angiogenesis and Neuroprotection after Ischemic Stroke in Humans. Stroke 1997, 28, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arimura, K.; Ago, T.; Kamouchi, M.; Nakamura, K.; Ishitsuka, K.; Kuroda, J.; Sugimori, H.; Ooboshi, H.; Sasaki, T.; Kitazono, T. PDGF Receptor β Signaling in Pericytes Following Ischemic Brain Injury. Curr. Neurovasc. Res. 2012, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chintalgattu, V.; Ai, D.; Langley, R.R.; Zhang, J.; Bankson, J.A.; Shih, T.L.; Reddy, A.K.; Coombes, K.R.; Daher, I.N.; Pati, S.; et al. Cardiomyocyte PDGFR-Beta Signaling Is an Essential Component of the Mouse Cardiac Response to Load-Induced Stress. J. Clin. Invest. 2010, 120, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakai, K.; Takata, F.; Yamanaka, G.; Yasunaga, M.; Hashiguchi, K.; Tominaga, K.; Itoh, K.; Kataoka, Y.; Yamauchi, A.; Dohgu, S. Reactive Pericytes in Early Phase Are Involved in Glial Activation and Late-Onset Hypersusceptibility to Pilocarpine-Induced Seizures in Traumatic Brain Injury Model Mice. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 145, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arango-Lievano, M.; Boussadia, B.; De Terdonck, L.D.T.; Gault, C.; Fontanaud, P.; Lafont, C.; Mollard, P.; Marchi, N.; Jeanneteau, F. Topographic Reorganization of Cerebrovascular Mural Cells under Seizure Conditions. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 1045–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbelli, R.; de Bock, F.; Medici, V.; Rousset, M.C.; Villani, F.; Boussadia, B.; Arango-Lievano, M.; Jeanneteau, F.; Daneman, R.; Bartolomei, F.; et al. PDGFRβ(+) Cells in Human and Experimental Neuro-Vascular Dysplasia and Seizures. Neuroscience 2015, 306, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milesi, S.; Boussadia, B.; Plaud, C.; Catteau, M.; Rousset, M.-C.; De Bock, F.; Scheffer, M.; Lerner-Natoli, M.; Rigau, V.; Marchi, N. Redistribution of PDGFRβ Cells and NG2DsRed Pericytes at the Cerebrovasculature after Status Epilepticus. Neurobiol. Dis. 2014, 0, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klement, W.; Garbelli, R.; Zub, E.; Rossini, L.; Tassi, L.; Girard, B.; Blaquiere, M.; Bertaso, F.; Perroy, J.; de Bock, F.; et al. Seizure Progression and Inflammatory Mediators Promote Pericytosis and Pericyte-Microglia Clustering at the Cerebrovasculature. Neurobiol. Dis. 2018, 113, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalski, D.; Spielvogel, E.; Puchta, J.; Reimann, W.; Barthel, H.; Nitzsche, B.; Mages, B.; Jäger, C.; Martens, H.; Horn, A.K.E.; et al. Increased Immunosignals of Collagen IV and Fibronectin Indicate Ischemic Consequences for the Neurovascular Matrix Adhesion Zone in Various Animal Models and Human Stroke Tissue. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 575598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, N.M.; Trevisan, C.; Leifsson, P.S.; Johansen, M.V. The Association between Seizures and Deposition of Collagen in the Brain in Porcine Taenia Solium Neurocysticercosis. Vet. Parasitol. 2016, 228, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liesi, P.; Kauppila, T. Induction of Type IV Collagen and Other Basement-Membrane-Associated Proteins after Spinal Cord Injury of the Adult Rat May Participate in Formation of the Glial Scar. Exp. Neurol. 2002, 173, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özkan, E.; Çetin-Taş, Y.; Şekerdağ, E.; Kızılırmak, A.B.; Taş, A.; Yıldız, E.; Yapıcı-Eser, H.; Karahüseyinoğlu, S.; Zeybel, M.; Gürsoy-Özdemir, Y. Blood-Brain Barrier Leakage and Perivascular Collagen Accumulation Precede Microvessel Rarefaction and Memory Impairment in a Chronic Hypertension Animal Model. Metab. Brain Dis. 2021, 36, 2553–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veznedaroglu, E.; Van Bockstaele, E.J.; O’Connor, M.J. Extravascular Collagen in the Human Epileptic Brain: A Potential Substrate for Aberrant Cell Migration in Cases of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. J. Neurosurg. 2002, 97, 1125–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowenstein, D.H.; Arsenault, L. Dentate Granule Cell Layer Collagen Explant Cultures: Spontaneous Axonal Growth and Induction by Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor or Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor. Neuroscience 1996, 74, 1197–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeppner, T.J.; Morrell, F. Control of Scar Formation in Experimentally Induced Epilepsy. Exp. Neurol. 1986, 94, 519–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racine, R.J. Modification of Seizure Activity by Electrical Stimulation. II. Motor Seizure. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1972, 32, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soussi, R.; Boulland, J.-L.; Bassot, E.; Bras, H.; Coulon, P.; Chaudhry, F.A.; Storm-Mathisen, J.; Ferhat, L.; Esclapez, M. Reorganization of Supramammillary-Hippocampal Pathways in the Rat Pilocarpine Model of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy: Evidence for Axon Terminal Sprouting. Brain Struct. Funct. 2015, 220, 2449–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajorat, R.; Wilde, M.; Sellmann, T.; Kirschstein, T.; Köhling, R. Seizure Frequency in Pilocarpine-Treated Rats Is Independent of Circadian Rhythm. Epilepsia 2011, 52, e118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerholz, DK.; Beck, AP. Principles and approaches for reproducible scoring of tissue stains in research. Lab Invest. 2018 Jul;98(7):844-855. Epub 2018 May 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, SW.; Roh, J.; Park, CS. Immunohistochemistry for Pathologists: Protocols, Pitfalls, and Tips. J Pathol Transl Med. 2016 Nov;50(6):411-418. Epub 2016 Oct 13. PMCID: PMC5122731. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paxinos, G.; Watson, C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates, 4th Edition. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, USA.; 1998, ISBN 0125476183.

- Sbai, O.; Ould-Yahoui, A.; Ferhat, L.; Gueye, Y.; Bernard, A.; Charrat, E.; Mehanna, A.; Risso, J.-J.; Chauvin, J.-P.; Fenouillet, E.; et al. Differential Vesicular Distribution and Trafficking of MMP-2, MMP-9, and Their Inhibitors in Astrocytes. Glia 2010, 58, 344–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagano, A.; Breuzard, G.; Parat, F.; Tchoghandjian, A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; De Bessa, T.C.; Garrouste, F.; Douence, A.; Barbier, P.; Kovacic, H. Tau Regulates Glioblastoma Progression, 3D Cell Organization, Growth and Migration via the PI3K-AKT Axis. Cancers 2021, 13, 5818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvani, G.; Romanov, V.; Cox, C.D.; Martinac, B. Biomechanical Characterization of Endothelial Cells Exposed to Shear Stress Using Acoustic Force Spectroscopy. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 612151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell, R.B.; Holleran, S.; Ramakrishnan, R. Sample Size Determination. ILAR J. 2002, 43, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Festing, M.F.W.; Altman, D.G. Guidelines for the Design and Statistical Analysis of Experiments Using Laboratory Animals. ILAR J. 2002, 43, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haq, S.; Sarodaya, N.; Karapurkar, J.K.; Suresh, B.; Jo, J.K.; Singh, V.; Bae, Y.S.; Kim, K.-S.; Ramakrishna, S. CYLD Destabilizes NoxO1 Protein by Promoting Ubiquitination and Regulates Prostate Cancer Progression. Cancer Lett. 2022, 525, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharvit, E.; Abramovitch, S.; Reif, S.; Bruck, R. Amplified Inhibition of Stellate Cell Activation Pathways by PPAR-γ, RAR and RXR Agonists. PloS One 2013, 8, e76541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene name | Gene description | Probe ID |

| Gfap | Glial fibrillary acid protein | Rn01253033 |

| Iba1 | Ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule1 | Rn00574125 |

| CD31 or PECAM-1 | EndoCAM or Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 | Rn01467262 |

| PDGFRβ | Platelet-derived growth factor beta | Rn01502596 |

| ColIV a1 | Collagen, type IV, a1 | Rn01482927 |

| ColIV a3 | Collagen, type IV, a3 | Rn01400991 |

| RPL13 | Ribosomal Protein L13 | Rn00821258 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).