1. Introduction

Social capital comprises a collective set of norms, values, and practices that facilitate collaboration among individuals and groups. At the core of this construct lies trust, predicated on the assumption that individuals in society generally exhibit reliability, trustworthiness, and fairness (Alesina and La Ferrara, 2002; Glaeser et al., 2000). This foundational element of trust serves as the cornerstone for fostering positive and efficacious interpersonal interactions within various social milieus.

The role of trust in social interactions is indispensable, functioning as a critical metric for assessing the reliability and integrity of the interacting parties (Rotter, 1967; Sobel, 2002). In scenarios devoid of trust, individuals find themselves without the requisite information for informed decision-making, thereby obstructing the potential for meaningful social engagement. For instance, consumers place faith in corporations to furnish quality goods and services, while individuals entrust financial institutions with the stewardship of their monetary and retirement assets. In healthcare contexts, patients rely upon medical professionals to administer optimal care, often without the capability for independent quality assessment.

A deficit in trust and trustworthiness can introduce significant challenges in ensuring compliance with social and economic agreements. Such a deficit often necessitates the imposition of sanctions, regulatory oversight, or alternative enforcement mechanisms to secure adherence. The absence of trust thereby elevates the risk of transactional failures, engendering adverse consequences for the involved parties and attenuating the overall efficacy and scope of economic activities (Zak and Knack, 2001).

Prior research posits that levels of trust within a population are generally lower in societies marked by extensive social diversity, whereas more homogeneous communities tend to exhibit higher trust levels. This suggests that a nation's social fabric, including the prevalence and diversity of ethnic and religious groups, exerts a significant influence on societal trust (Cook & Cooper, 2003; Kandori, 1988; Leigh, 2006; Zak and Knack, 2001). Furthermore, religion has been identified as a key variable affecting trust levels, with both the dominant faith within a nation and the interplay among multiple faiths contributing to this relationship (Bjørnskov, 2012; Delhey and Newton, 2005; La Porta et al., 1996; Zak and Knack, 2001).

Nigeria, a nation of extraordinary diversity, is home to over 250 distinct ethnic, linguistic, and religious groups, making it one of the most socially complex countries in Africa (The Central Intelligence Agency, 2018). This study aims to dissect the nuanced relationships between generalized trust and affiliations to specific religious and ethnic groups within a Nigerian sample. To achieve this, we employed the World Values Survey (WVS) questionnaire, disseminated in Nigeria in 2012. The incorporation of questions focused on generalized trust within broader socio-economic surveys facilitates interdisciplinary inquiries into the dynamics of social trust.

Our investigation seeks to quantify variations in generalized trust across diverse ethnic and religious demographics, while controlling for a multitude of variables including age, gender, marital status, educational attainment, income level, and urbanization. By scrutinizing the trust levels among various ethnic and religious constituencies in a multifaceted society like Nigeria, we aim to deepen our understanding of the intricate social dynamics not only within Nigeria but also in other societies characterized by a mosaic of ethnic and religious identities. Such an analysis offers invaluable insights into how disparate groups collectively shape a society's overarching cultural ethos.

2. Literature Review

Prior research has identified social trust as a pivotal element of social capital, a construct encompassing the collective norms, values, and mutual understandings that facilitate cooperation both within and among societal groups (Putnam and Goss, 2002; Rodríguez-Pose and von Berlepsch, 2014). The role of trust in underpinning effective societal functioning, driving economic efficiency, and its varying manifestations across diverse cultures has been the subject of extensive scholarly investigation (Brown and Uslaner 2005; Berggren and Jordahl 2006; Delhey and Newton 2005; Nannestad 2008).

While establishing causality remains challenging, empirical studies have consistently demonstrated a correlation between levels of social trust and key indicators of societal and economic well-being. For instance, Knack and Keefer (1997) leveraged multi-country data to establish a link between elevated levels of social trust and increased per capita GDP. Similarly, robust correlations have been observed between high social trust and a range of positive outcomes, including economic efficiency and growth (Berggren et al., 2008; Bjørnskov, 2012; Knack, 1999a; Knack and Keefer, 1997; Zak and Knack, 2001), elevated rates of educational enrollment (Bjørnskov 2009; Papagapitos and Riley 2009), governmental stability (Knack, 1999b; Nooteboom, 2007; Rothstein and Uslaner, 2005), enhanced legal system efficacy, more streamlined governmental bureaucracy, reduced corruption levels (Guiso et al., 2004; La Porta et al., 1996), and heightened life satisfaction (Helliwell et al., 2014).

By synthesizing these findings, it becomes evident that social trust serves as a linchpin for a multitude of factors that contribute to the overall health, stability, and prosperity of societies.

Trust and credibility serve as essential catalysts that streamline interactions and financial transactions, facilitate access to credit, and minimize the resources required for safeguarding property rights and ensuring compliance. By reducing transaction costs, these elements foster greater collaboration and stimulate business activities (Knack and Keefer, 1997). In numerous instances, traditional enforcement mechanisms like sanctions or guarantees are insufficient or impractical for ensuring that contracts are executed as per mutual expectations. Knack (1999a) posits that in societies where a baseline level of trust exists among strangers, trade and commerce occur more fluidly. Conversely, a deficit in trust and credibility can often lead to transactional failures, negatively impacting both individual stakeholders and the broader economy. Such a lack not only hampers individual transactions but also constrains the overall scope and efficacy of economic activities (Zak and Knack, 2001). Therefore, trust and credibility are not merely facilitative but are foundational to the effective functioning of economic systems.

Research underscores the pivotal role of social trust in enhancing team performance and fostering collaboration. Jones and George (1998) established a robust correlation between intra-team trust and both team performance and collaborative efforts. Similarly, Mach et al. (2010) explored the realm of sports teams and identified a significant relationship between trust in the team's coach and the team's overall performance. Trust is inherently a risk-laden venture for the trustor, predicated on the expectation that the trustee will act in good faith and prove trustworthy (Rousseau et al., 1998).

While social trust can be a catalyst for economic efficiency when both parties are reliable, it can also backfire when one or both parties prove untrustworthy. In such cases, misplaced trust becomes a liability rather than an asset. Academic investigations have revealed that misplaced trust in untrustworthy individuals or organizations is a recurring theme in successful fraudulent activities (Bayer, 2019; Hough, 2004). Thus, while trust serves as a cornerstone for positive social and economic interactions, it also carries the potential for negative outcomes when misapplied.

Prior scholarship on social trust has delineated two distinct types: generalized trust and personalized trust. Generalized trust refers to the level of trust one extends to strangers, while personalized trust is specific to individuals one knows personally (Stolle, 1998). The extent to which individuals believe that the majority of people can be trusted is encapsulated by the term generalized trust (Cook, 2016; Nieminen et al., 2008; Putnam, 2000).

The trust dynamics between individuals are shaped by a complex interplay of factors, including the characteristics of their social and communal settings as well as their personal experiences. Individual trust levels are influenced by a myriad of elements such as worldviews, cultural norms, values, and various socio-economic indicators like employment status, income, and educational level (Alesina and La Ferrara, 2002). Knack and Keefer (1997) posited a strong correlation between educational attainment and social trust, arguing that higher levels of education lead to better-informed individuals who are more adept at processing information and understanding the potential consequences of actions—both their own and those of others. They further contended that education serves a socializing function, making individuals more predisposed to trust others. Putnam (2000) suggested that social trust is nurtured through repeated interactions where individuals build confidence in one another, citing educational settings as a prime example of such interactional spaces.

Perceptions of social injustice stemming from inequality can erode trust, particularly among individuals who are more susceptible to racial or gender-based discrimination (Brockner & Siegel, 1996). Existing research has established a connection between socio-economic status and levels of social trust (Alesina & La Ferrara, 2002; Hamamura, 2012). Individuals who encounter discrimination or disrespect due to lower social standing often develop psychological defense mechanisms (Henry, 2009), which can subsequently result in diminished trust (Brandt & Henry, 2012; Brandt et al., 2015).

The role of social networks in fostering trust has received substantial scholarly attention (Granovetter, 1985; Coleman, 1988; Putnam, 2000). Group affiliation emerges as a potent factor influencing trust levels; individuals are generally more inclined to trust members of their own group, owing to the expectation of ethical conduct within that circle (Platow et al., 2012; Tanis & Postmes, 2005). Alesina et al. (2004) posit that individuals who have resided in a specific locale for an extended duration and have deeply integrated into its social and cultural fabric are more likely to exhibit elevated levels of trust.

The national landscape of social trust is also shaped by demographic composition. Zak and Knack (2001) discovered an inverse relationship between population diversity and overall trust levels. Leigh (2006) conducted a cross-national study and found that societal trust levels were negatively correlated with both economic inequality and ethnic diversity. Subsequent research has corroborated these findings, indicating that ethnic heterogeneity is associated with diminished trust levels (Cook & Cooper, 2003; Kandori, 1988).

Religious factors further contribute to the trust equation. The dominant faith within a country, as well as the interplay among various religious groups, has been shown to correlate with societal trust levels (Bjørnskov, 2012; Delhey and Newton, 2005; La Porta et al., 1996; Zak and Knack, 2001). Thus, trust is a multifaceted construct, influenced by a complex array of social, cultural, and demographic variables.

3. Nigeria's Population

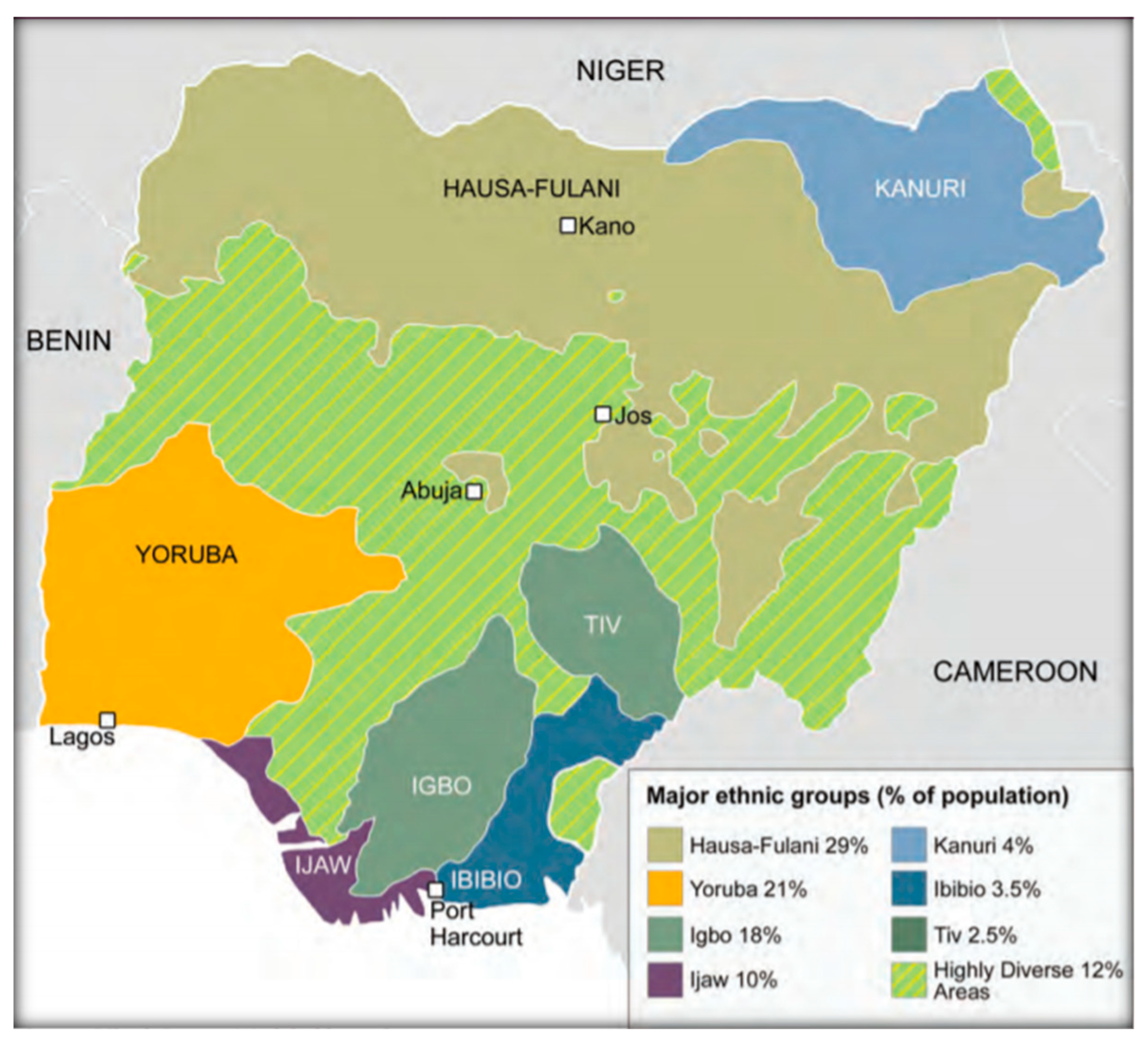

Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa, with an estimated population of approximately 196 million

1, accounting for nearly one-fifth of the continent's total population (The World Bank, 2018). This demographic significance positions Nigeria as the seventh most populous nation globally. The country is home to a remarkably diverse population, comprising over 250 distinct ethnic, religious, linguistic, and cultural groups. In the religious landscape, Nigeria is predominantly characterized by Islam and Christianity as the major faiths. The primary ethnic groups shaping the nation's demographic profile are the Hausa-Fulani, the Yoruba, and the Igbo (The Central Intelligence Agency, 2018).

Figure 1.

Major ethnic groups of Nigeria. Source: Kwaja, 2011.

Figure 1.

Major ethnic groups of Nigeria. Source: Kwaja, 2011.

According to data from the Central Intelligence Agency (2018), Nigeria's population is ethnically constituted as follows: Hausa at 27.4%, Yoruba at 21%, Igbo (Ibo) at 14.1%, Fulani at 6.3%, Tiv at 2.2%, Ibibio at 2.2%, Ijaw/Izon at 2%, and Kanuri/Beriberi at 1.7%, with other ethnic groups comprising 23.1%. In terms of religious affiliation, the population is segmented into Muslim at 53.5%, Roman Catholic at 10.6%, other Christian denominations at 35.3%, and other faiths or belief systems at 6%. The country also hosts a small minority who adhere to traditional African religions.

Nigeria has experienced a notable escalation in inter-ethnic conflicts, leading to the displacement of thousands of individuals. These conflicts are deeply entrenched in a complex tapestry of historical, political, economic, social, and cultural disparities, as well as episodes of discrimination and violence. One of the most recent manifestations of this tension is the Boko Haram insurgency, initiated in 2009, which has primarily set the largely Muslim Hausa-Fulani against the predominantly Christian Igbo and Yoruba communities in the northern regions, with both factions perpetrating acts of violence against civilians. Additional conflicts within Nigeria encompass the discord between the Tiv and Jukun ethnic groups, the contention between the Ogoni community and Shell Oil Company over natural resource exploitation, and ongoing clashes between farmers and herders (Eke, 2020; Olagbaju & Awosusi, 2019).

According to the 2021 Corruption Perception Index (CPI) released by Transparency International, Nigeria is ranked 149th out of 180 countries, scoring 25 out of 100, a slight decline from its score of 27 in 2012 (Transparency International, 2021

2). This data suggests that corruption is perceived as a pervasive issue in the country, potentially undermining trust in public institutions and interpersonal relationships.

Urban conflicts in Nigeria include a range of issues such as crime, violence, drug trafficking, and civil disturbances (Ojo & Ojewale, 2019). We posit that such violence and civil unrest have significantly impacted the level of trust among Nigeria's diverse ethnic and religious communities, likely exacerbating feelings of fear and insecurity, thereby hindering the development of mutual trust. Furthermore, we contend that Nigeria's elevated poverty rates, including a substantial segment of the population living in extreme poverty (World Bank, 2020), could adversely influence trust levels.

Drawing on data from the World Values Survey (WVS), this study aims to investigate the interplay between ethnic origin, religious affiliation, and levels of trust within Nigeria's multicultural context, while also considering other contributory factors. The inquiry is informed by Nigeria's demographically diverse landscape and is grounded in previous research findings and methodologies.

3.1. The Research Population and the WVS Questionnaire

The data employed in this study originates from the most recent wave

3 of the World Values Survey (WVS)

4 for Nigeria, collected in 2012. The WVS serves as a collaborative network of social scientists dedicated to researching shifts in societal values and their subsequent impact on social and political dynamics. Adapted to suit each of the 100 participating countries, the WVS questionnaires encompass a broad range of topics, including demographics, beliefs, values, and cultural norms (Inglehart et al., 2014). Included among these questions is one that pertains to generalized social trust.

The 2012 iteration of the survey in Nigeria featured 1,759 respondents, ranging in age from 18 to 98. Generalized trust was assessed through a self-report questionnaire that probed each participant's level of trust in others. Given the comprehensive scope of the questionnaire and the robust sample size, the data allows for statistical analysis of generalized social trust, incorporating relevant control variables.

Table 1 delineates the primary variables employed in this research.

We hypothesized that variations in trust levels would exist between different religious and ethnic groups, likely attributable to cultural distinctions. Our initial assumptions regarding trust among these groups were complex and not unidimensional. On one hand, we expected that majority ethnic groups in Nigeria would exhibit higher levels of trust compared to minority groups. This supposition was grounded in the notion that minority groups in a multicultural setting are less inclined to extend trust to individuals outside their immediate social circle. Conversely, as indicated in

Table 1, certain ethnic groups in Nigeria predominantly reside in specific geographic regions. As a result, some smaller ethnic groups situated in geographically homogeneous areas may display relatively elevated levels of trust toward their immediate neighbors.

We also hypothesized that demographic factors would correlate with trust levels in a manner consistent with existing literature, as outlined in our literature review. Specifically, we anticipated that individuals with higher incomes and advanced educational attainment would be more likely to exhibit higher levels of trust (Knack and Keefer, 1997). Furthermore, we posited that residents of smaller communities would likely be more trusting, based on the assumption that smaller communities foster greater familiarity among inhabitants.

3.2. Generalized Trust: Descriptive Statistics

The following table presents the attributes of the research sample (

Table 2):

In the World Values Survey (WVS) rendition of the generalized trust query, participants were prompted to select one of two statements: "Most people can be trusted" or "Need to be very careful."

Table 3 delineates the distribution of responses to this generalized trust question within the research sample:

Table 3 reveals that a substantial majority—exceeding 85%—of respondents advocate for caution in trusting others. This percentage is notably lower than the average rate of 23.8% observed across countries surveyed in Wave 6 of the WVS. Conversely, data from several developing nations reported even lower rates, with some countries like the Philippines and Trinidad and Tobago registering single-digit percentages (e.g., 3.2%).

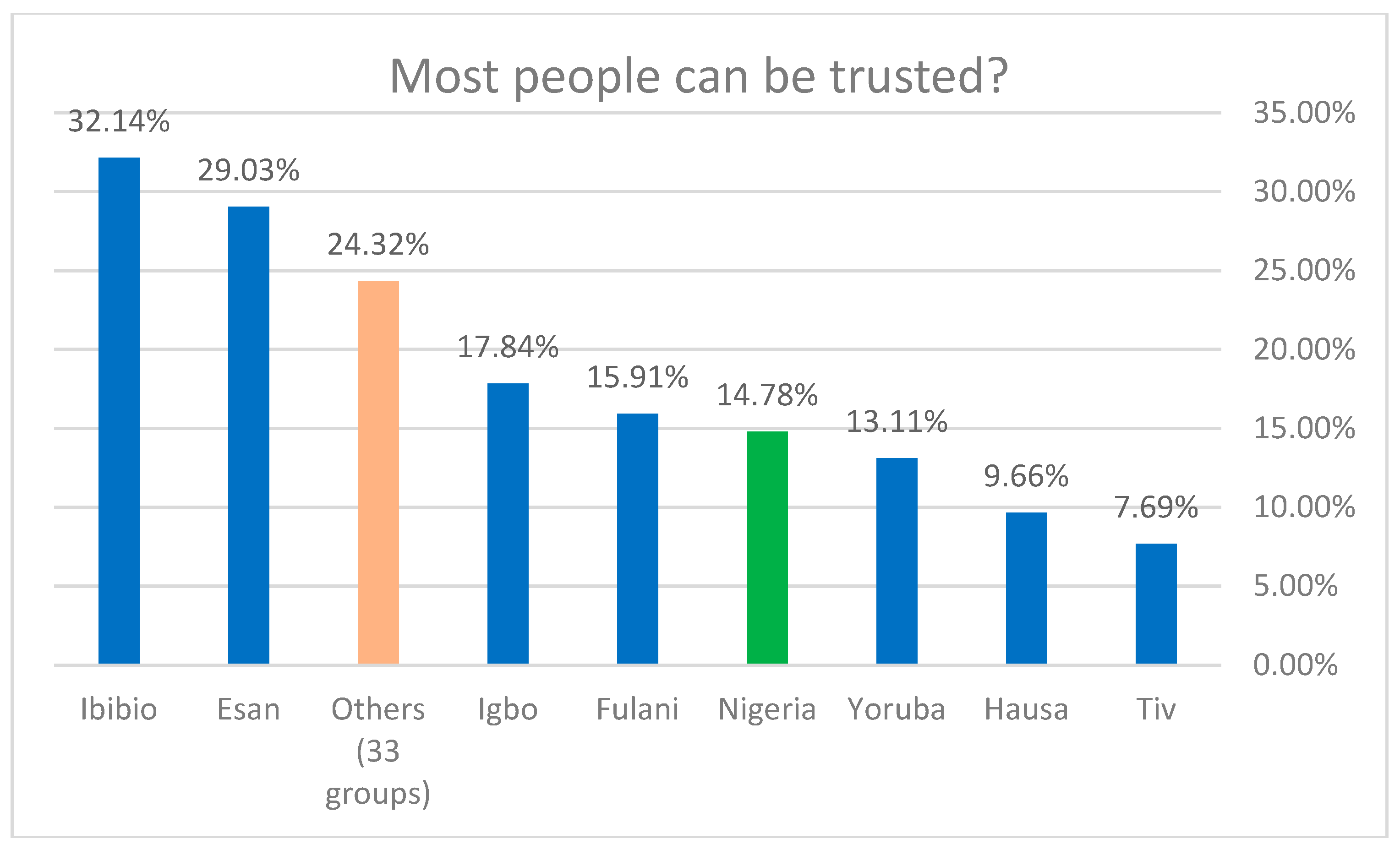

To explore the potential correlation between the proportion of respondents who believe that most people can be trusted and variables such as ethnic and religious affiliations, the responses were segmented by the primary ethnic and religious groups. The ensuing figure presents the distribution of trust responses by ethnic group and includes data from all respondents who answered the question (N = 1759).

The chart depicted in

Figure 2 elucidates the relationship between ethnic affiliation and the proportion of respondents who consider most people to be trustworthy. Evidently, there are discernible disparities in trust levels across the various ethnic groups. Among the Ibibio respondents, the highest percentage—32.14%—believed that most people can be trusted. Conversely, the Tiv respondents registered the lowest percentage, at 7.69%.

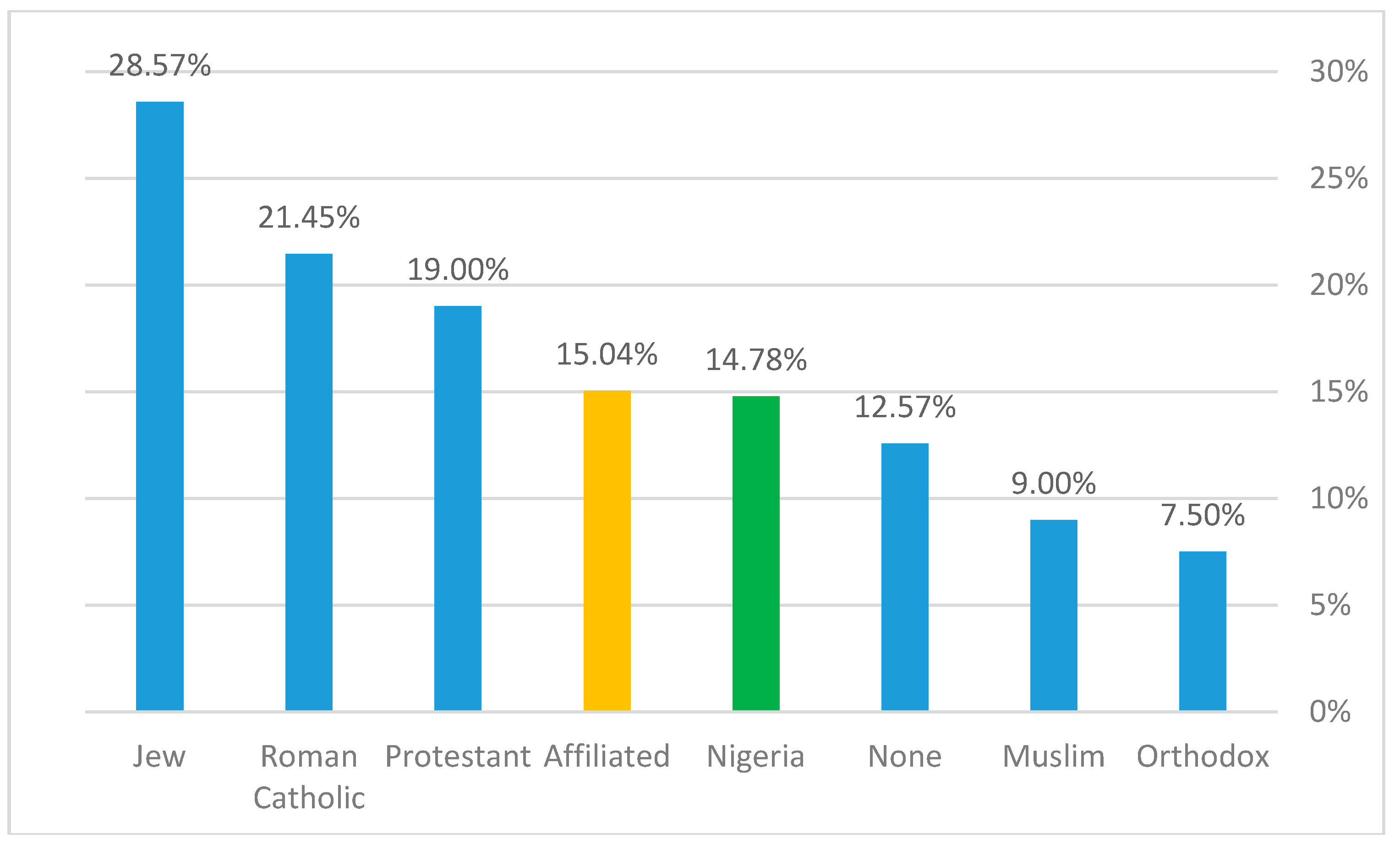

Figure 3 illustrates the differences in the percentages of people within different religious groups who believe that most people can be trusted. Notably, there are discrepancies in the level of trust between diverse religious groups. The data shows that the highest level of trust is among those who identify as Jewish, with 28.57%, and those who identify as Roman Catholic, with 21.45%, feeling that most people can be trusted. On the other hand, the lowest level of trust is among Muslims, with 9%, and Orthodox followers, with only 7.5%, feeling the same. Without considering other factors, it appears that the largest religious group in Nigeria, Muslims, does not exhibit particularly high levels of social trust at 9%. Overall, levels of trust vary substantially between different ethnic and religious groups.The data about religious and ethnic affiliation shows a correlation between the two facets in some populations. The Hausa people are largely adherents of Islam (78%), whereas, in other ethnic groups, there is a split between different religious affiliations. To account for additional explanatory variables as well as the correlation between religion and ethnic identity, the results part will examine a deeper analysis of the data using multi-variable models.

4. Results

To conduct a nuanced analysis of the data, we employed probit estimation models for statistical evaluation, incorporating various control variables to more precisely scrutinize the relationship between generalized trust and the dependent variables.

Table 4 showcases the outcomes of five distinct probit estimations related to the WVS question on generalized trust. In these models, the dependent variable is coded as '1' for respondents who believe that most people can be trusted and '0' for those who do not hold this view. Our analytical approach involved iteratively adding variables to the model during the course of the analysis. The initial model solely incorporates the variable of religious group affiliation (Model 1), while the final model (Model 5) includes all pertinent explanatory variables.

We evaluated multiple models and opted to present those that were most statistically significant and relevant. Model 2 incorporates the variable of ethnic group affiliation, while Model 3 includes both religious and ethnic group affiliations. Model 4 extends this by adding gender and age to the religious and ethnic affiliation variables. Finally, Model 5 further enriches the analysis by including variables for level of education, income, and size of the town.

Model 1 uncovers a correlation between certain religious affiliations and a propensity to trust others when other respondent characteristics are not accounted for. Specifically, Protestants, Roman Catholics, and Jews exhibit a statistically significant higher tendency to trust others compared to Muslims, who serve as the baseline group. Model 2 reveals that, absent other respondent characteristics, ethnic group affiliation is correlated with generalized trust in certain instances. Specifically, individuals affiliated with the Igbo, Ibibio, Esan, and "others" groups display a statistically significant higher tendency to trust others, while Yoruba shows a lower level of statistical significance, all relative to the Hausa (the baseline group).

The findings suggest that majority groups are generally less trusting than some minority groups. This pattern is somewhat attenuated when additional variables such as age, education level, income level, and locality size are incorporated into the model. In certain cases (all the religious groups mentioned, as well as the Ibibio and Fulani ethnic groups), disparities in trust levels persist even after these variables are included.

An exploration of interactions between religious and ethnic affiliations was undertaken, but no enhancements to any of the models were observed. It is important to interpret the results of the multivariate model cautiously, especially for ethnic and religious groups with relatively small sample sizes, such as the Fulani, Tiv, Ibibio, and Esan ethnic groups, and Orthodox, Jewish, Hindu, and "Others" in the religious categories.

Model 4's results indicate a correlation between age and a diminished propensity to trust others, a finding that deviates from previous research conducted in Western contexts (Bayer, 2013; Bayer, 2020; Sutter and Kocher, 2007). Additionally, Model 4 reveals a correlation of low statistical significance between gender and generalized trust, suggesting that women are less likely to trust others compared to men. This aligns with prior Western research indicating lower trust levels among women (Rau, 2011), although this correlation loses its statistical significance in Model 5.

A standalone probit model focusing solely on the level of education as an explanatory variable identifies a positive correlation between higher educational attainment (complete secondary and above) and generalized trust, corroborating earlier research (Alesina et al., 2002). However, when ethnic and religious affiliations are included in the model, the correlation between different levels of formal education and trust becomes statistically insignificant. Contrary to existing literature that suggests a positive relationship between education and trust, this particular model reveals a negative correlation with weak statistical significance at two levels of formal education, a result that calls for further investigation.

Model 5 suggests a statistically significant relationship between an individual's income level and their tendency to trust, indicating that those with higher incomes are generally more trusting than those with lower incomes. This is consistent with previous studies (Knack and Keefer, 1997).

Regarding the variable related to the size of the place of residence, the results are not uniformly statistically significant. However, the statistically significant outcomes do support the initial hypothesis that residents of smaller localities are more likely to trust others. Specifically, individuals residing in larger cities (100,001-500,000 inhabitants) exhibit lower trust levels compared to those in smaller towns (50,001-100,000, the baseline). Furthermore, those in small towns (5,001-10,000 inhabitants) appear to have higher trust levels than those in the baseline larger towns. Although we anticipated higher trust levels in even smaller communities (below 5,000 inhabitants) based on prior research, these results were not statistically significant, possibly due to the limited sample size for these smaller localities (ranging from 2,001-5,000 inhabitants and fewer than 2,000 inhabitants).

5. Conclusions and Discussion

The notably low levels of generalized trust in Nigeria could be ascribed to its considerable population diversity, which encompasses over 250 distinct ethnic groups (CIA, 2018). This observation aligns with existing literature positing that residing in a highly heterogeneous society can contribute to diminished levels of trust, potentially affecting broad segments of the population. Compounding this issue, Nigeria's diverse populace has a history of inter-ethnic conflicts. Furthermore, the country grapples with elevated poverty rates, with a significant proportion of its citizens living in extreme poverty (World Bank, 2020). These factors—social unrest, poverty, and instability—may collectively exert a substantial downward pressure on the country's overall trust levels, potentially amplifying feelings of fear and insecurity and thereby inhibiting interpersonal trust. Despite these challenges, it is noteworthy that Nigeria's generalized trust levels exceed those of many other surveyed developing nations.

The findings of this study reveal a significant association between ethnic and religious affiliations and levels of generalized trust. Distinct religious and ethnic groups exhibited varying degrees of social trust, which is likely influenced by unique cultural attributes such as shared values, beliefs, and customs. Additionally, intergroup relations—how these ethnic and religious groups interact with one another—may also play a crucial role in shaping trust levels. The dynamics of these interactions, whether characterized by cooperation or conflict, could further influence the trust landscape within these diverse communities.

Incorporating additional explanatory variables into the model yielded intriguing outcomes. Specifically, individual ethnicity and religiosity emerged as potent factors in shaping trust disparities in Nigeria, in some instances outweighing personal and demographic characteristics.

Remarkably, the study uncovers that certain smaller ethnic groups manifest higher average levels of generalized trust compared to larger groups. Notably, the largest ethnic groups—primarily the Hausa (who are mostly Muslim) and the Yoruba (who are partly Muslim)—exhibited lower levels of generalized trust compared to other groups. The reduced trust levels among the Muslim population could potentially be linked to their involvement in ongoing struggles for governance changes and ethnic conflicts within the country. This intriguing observation warrants further, more detailed investigation. This challenges the conventional wisdom that majority groups are more likely to engender higher levels of social trust. These results may be attributable to Nigeria's diverse social fabric, where various groups are geographically dispersed, with some smaller ethnic groups residing in more culturally homogeneous regions. However, the limited sample size for these smaller groups makes it challenging to delve deeply into these variations. Future research could explore the trust levels, social structures, and intergroup conflicts within these smaller communities, although such an investigation was beyond the scope of the current study due to sample limitations.

In certain instances, the study revealed that the influence of cultural disparities on trust levels appears to diminish when demographic variables are incorporated into the analytical model. This suggests that, at least in some cases, individual attributes may exert a substantial impact on levels of trust, potentially overshadowing the role of cultural factors.

It's important to note that the study's reliance on single-period questionnaire data limits its ability to track changes in social trust over different time frames.

Declaration of Interest Statement

The author of this article declares that he has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Alesina, A., & La Ferrara, E. (2002). Who trusts others?. Journal of public economics, 85(2), 207-234.

- Alesina, A., Baqir, R. and Hoxby, C. (2004 ), ‘Political Jurisdictions in Heterogeneous Communities’, Journal of Political Economy, 112, 348– 96.

- Bayer, Yaakov (2013) Economic and psychological aspects of aging, Beer-Sheva: Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. [Hebrew].

- Bayer, Y. M. (2019) Older Adults, Aggressive Marketing, Unethical Behavior: A Sure Road to Financial Fraud? In Gringarten, H. & Fernández- Calienes, R. (Ed.) Ethical Branding and Marketing: Cases and Lessons. New York. Rutledge Publishing.

- Bayer, Y.M. (2023) Age and Generalized Trust in the United States: What Do WVS Data Say? Preprints 2023, 2023091696. [CrossRef]

- Bellemare, C., & Kröger, S. (2007). On representative social capital. European Economic Review, 51(1), 183-202.

- Berggren, N. and Jordahl, H. (2006) “Free to Trust: Economic Freedom and Social Capital,” Kyklos 59(2): 141–169.

- Berggren, N., Elinder, M., & Jordahl, H. (2008). Trust and growth: a shaky relationship. Empirical Economics, 35(2), 251-274.

- Bjørnskov, C. (2009). Social trust and the growth of schooling. Economics of education review, 28(2), 249-257.

- Bjørnskov, C. (2012). How does social trust affect economic growth? Southern Economic Journal, 78(4), 1346-1368.

- Brandt, M. J., & Henry, P. J. (2012). Psychological defensiveness as a mechanism explaining the relationship between low socioeconomic status and religiosity. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 22(4), 321-332.

- Brandt, M. J., Wetherell, G., & Henry, P. J. (2015). Changes in income predict change in social trust: A longitudinal analysis. Political Psychology, 36(6), 761-768.

- Brockner, J. and Siegel, P. (1996 ), ‘Understanding the Interaction Between Procedural and Distributive Justice’, in R.M. Kramer and T.R. Tyler (eds), Trust in Organizations, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA; 390– 413.

- Brown, M. and Uslaner, E. M. (2005) “Inequality, Trust, and Civic Engagement,” American.

-

Politics Research 33(6): 868–894.

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American journal of sociology, 94, S95-S120.

- Cook, K. (2016). Trust. In Ritzer, G., editor, The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Cook, K. and Cooper, R. (2003 ), ‘Experimental Studies of Cooperation, Trust, and Social Exchange’, in E. Ostrom and J. Walker (eds), Trust and Reciprocity, Interdisciplinary Lessons from Experimental Research, Russell Sage Foundation, New York; 209– 44.

- Delhey, J. and Newton, K. (2005) “Predicting Cross-national Levels of Social Trust: Global.

- Pattern or Nordic Exceptionalism?” European Sociological Review 21(4): 311–327.

- Eke, S. (2020). ‘Nomad savage’and herder–farmer conflicts in Nigeria: the (un) making of an ancient myth. Third World Quarterly, 41(5), 745-763.

- Erikson, E. H. (1993). Childhood and society. WW Norton & Company.

- Fehr, E., Fischbacher, U., von Rosenbladt, B., Schupp, J., Wagner, G.G. (2003) A nationwide laboratory. Examining trust and trustworthiness by integrating behavioral experiments into representative surveys. Working paper 141. Institute for Empirical Research in Economics. University of Zurich.

- Glaeser, E. L., Laibson, D., & Sacerdote, B. (2002). An economic approach to social capital. The economic journal, 112(483), F437-F458.

- Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American journal of sociology, 91(3), 481-510.

- Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2004). The role of social capital in financial development. American economic review, 94(3), 526-556.

- Hamamura, T. (2012) Social class predicts generalized trust but only in wealthy societies. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 43(3), 498-509.

- Helliwell, J. F., Huang, H., & Wang, S. (2014). Social capital and well-being in times of crisis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(1), 145-162.

- Henry, P. J. (2009). Low-status compensation: A theory for understanding the role of status in cultures of honor. Journal of personality and social psychology, 97(3), 451.

- Hough, M. (2004). Exploring elder consumers’ interactions with information technology. Journal of Business & Economics Research, 2(6), 61–66.

- Inglehart, R., C. Haerpfer, A. Moreno, C. Welzel, K. Kizilova, J. Diez-Medrano, M. Lagos, P. Norris, E. Ponarin & B. Puranen et al. (eds.). 2014. World Values Survey: Round Six - Country-Pooled Data file Version: http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV6.jsp. Madrid: JD Systems Institute.

- Jones, G.R., George, J.M. (1998). The experience and evolution of Trust: implications for cooperation and teamwork, Academy of Management Review, 23 (3) 531-546.

- Kandori, M. (1988), ‘Monotonicity of Equilibrium Payoff Sets with Respect to Observability in Repeated Games with Imperfect Monitoring’, Institute for Mathematical Studies in the Social Sciences (IMSSS) Technical Report No. 523, Stanford University, Stanford, CA.

- Knack, S. (1999a). Social capital, growth and poverty: a survey and extensions. Social Capital Initiative Working Paper, Social Development Department. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Knack, S. (1999b). Social capital and the quality of government: Evidence from the United States: The World Bank.

- Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1997). Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. The Quarterly journal of economics, 112(4), 1251-1288.

- Kwaja, C. (2011). Nigeria's Pernicious Drivers of Ethno-Religious Conflict (Africa Security Brief, Number 14, July 2011). National Defense Univ. Washington DC Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

- La Porta, R., Lopez-De-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A. and Vishny, R.W. (1996), ‘Trust in Large Organizations’, American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings, 87, 333– 8.

- Leigh, A. (2006). Does equality lead to fraternity?. Economics letters, 93(1), 121-125.

- Mach, M., Dolan, S., & Tzafrir, S. (2010). The differential effect of team members' trust on team performance: The mediation role of team cohesion. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(3), 771-794.

- Nannestad, P. (2008) “What Have We Learned about Generalized Trust, If Anything?”.

-

Annual Review of Political Science 11: 413–436.

- Nieminen, T., Martelin, T., Koskinen, S., Simpura, J., Alanen, E., Härkänen, T., & Aromaa, A. (2008). Measurement and socio-demographic variation of social capital in a large population-based survey. Social Indicators Research, 85(3), 405-423.

- Nooteboom, B. (2007). Social capital, institutions and trust. Review of social economy, 65(1), 29-53.

- Olagbaju, O. O., & Awosusi, O. E. (2019). Herders-farmers’ communal conflict in Nigeria: An indigenised language as an alternative resolution mechanism. International Journal of Multidisciplinary and Current Research, 7.

- Ojo, A., & Ojewale, O. (2019). Urbanisation and crime in Nigeria. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Papagapitos, A., & Riley, R. (2009). Social trust and human capital formation. Economics Letters, 102(3), 158-160.

- Platow, M. J., Foddy, M., Yamagishi, T., Lim, L., & Chow, A. (2012). Two experimental tests of trust in in-group strangers: The moderating role of common knowledge of group membership. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42(1), 30-35.

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster.

- Putnam, R., & Goss, K. A. (2002). Introduction,[w:]. R. Putnam (ed.), Democracies in Flux. The Evolution of Social Capital in Contemporary Society. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Rau, H. A. (2011). Trust and trustworthiness: A survey of gender differences. Psychology of Gender Differences, Forthcoming.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Von Berlepsch, V. (2014). Social capital and individual happiness in Europe. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(2), 357-386.

- Rothstein, B., & Uslaner, E. M. (2005). All for all: Equality, corruption, and social trust. World politics, 58(1), 41-72.

- Rotter, J. B. (1967). A new scale for the measurement of interpersonal trust 1. Journal of personality, 35(4), 651-665.

- Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of management review, 23(3), 393-404.

- Simross, L. (1994). Scams, cons, and other hazards. DollarSense, pp. 6-9.

- Sutter, M., & Kocher, M. G. (2007). Trust and trustworthiness across different age groups. Games and Economic behavior, 59(2), 364-382.

- Sobel, J. (2002). Can we trust social capital? Journal of economic literature, 40(1), 139-154.

- Stolle, D. (1998). Bowling together, bowling alone: The development of generalized trust in voluntary associations. Political psychology, 497-525.

- Tanis, M., & Postmes, T. (2005). A social identity approach to trust: Interpersonal perception, group membership and trusting behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 35(3), 413-424.

- The Central intelligence agency (2018) Nigeria — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved from: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ni.html. (27.06.2020).

- The World Bank, Nigeria - Country Profile (2018). Population. Retrieved from: https://databank.worldbank.org/views/reports/reportwidget.aspx?Report_Name=CountryProfile&Id=b450fd57&tbar=y&dd=y&inf=n&zm=n&country=NGA (27/06/2020).

- Welzel, C. (2013). Freedom rising. Cambridge University Press.

- Zak, P. J., & Knack, S. (2001). Trust and growth. The economic journal, 111(470), 295-321.

| 1 |

According to the world bank data, Nigeria's population at 2012 was 167.2 million. Source: https://www.worldbank.org/ |

| 2 |

https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2021/index/nga |

| 3 |

At the time the study was conducted, 2-5/2020. |

| 4 |

www.worldvaluessurvey.org |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).