1. Introduction

In the United States, obesity, especially childhood obesity have been at the center of public health efforts, with nearly one-third of U.S. children and teens being overweight or obese [

1]. A major concern about childhood obesity is that the condition is likely to continue in adulthood, with serious risks of related chronic conditions [

2]. Similarly, diabetes and mental health impairment among children and adolescents are on the rise in the U.S., posing significant personal and social burdens [

3]. Furthermore, there are serious issues that affect kids that don’t have the right physical education and one that is noticeable is weight and obesity [

4]. Many children in low-income communities’ experience weight gain that leads to obesity and not only is it seen in poor neighborhoods but also in ethnic minorities [

5].

Physical inactivity and sedentary behavior are more prevalent among Hispanic Children from low incomes [

6]. Furthermore, Hispanic children exhibit a much higher rate of obesity than their white counterparts [

7]. Children with lower levels of fundamental movement skills (FMS) are more likely to become physically inactive and to become obese as they grow. Accordingly, the prevalence of FMS proficiency among U.S. children is low, and children from disadvantaged backgrounds often rank the lowest in FMS proficiency [

8]. Fundamental movement skills (FMS) are related to physical activity and are an important part of a child’s development, many children are growing into teenagers without having the right growth and development. Without these fundamental skills, children are risking serious health issues and impacting their academic performance [

9]. More research is needed to address the role of FMS on physical activity among young Hispanic children compared to non-Hispanic white elementary school children.

FMS provides the foundation for a child's physical and cognitive development, enabling them to function effectively in their daily lives [

10]. In schools, young children have the best opportunity to practice and apply fundamental movement skills. FMS, including locomotor skills such as running, leaping, and sliding, are frequently developed in early childhood, along with object-control skills such as dribbling, throwing, and passing. Furthermore, interventions should be prioritized because children develop substantial skills, habitual behaviors, and motivation for active living during the early years of school [

11]. In the United States, it is recommended that children get 60 minutes of physical activity each day. In order for Hispanic children to have access to physical activity and FMS growth, schools can be a valuable resource for them.

The aim of this study is to investigate fundamental movement skills and physical activity differences among Hispanic and non-Hispanic White elementary school children. In addition, a novel 8-week teacher-led physical activity intervention is being examined to determine the physiological health effects and improvement of motor skills in Hispanic children.

2. Materials and Methods

Design and Subjects

The present cross-sectional study recruited children from the city of Moorpark. Participants were pair matched for age, gender, and time of measurement (for season, school days/school holidays) and socio-economic status (SES). The paired design was intended to reduce the influence of factors other than ethnicity between the two groups and increase study power. Moorpark is a city in Ventura County in California, USA. According to the 2020 US Census data, Moorpark has a population of 36, 284 with a population density of 1,038.4/km2. The ethnic make-up of Moorpark consists of 76.8% White, 30.4% Hispanic/Latino, 1.6 %African American, 1.4 % American Indian/Alaska Native, 0.6% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. Moorpark has a median household income of $107,820, which is considered higher than the national median income of $67,251, however, this is offset by the high living cost of California, US. All six elementary schools agreed to participate in the study, but only three were randomly selected. The study included 196 4- to 11-year-old children from kindergarten, 2nd, and 5th grades. Parental consent was obtained from all parents, and children consented voluntarily. Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Anthropometric Measurements

Using a beam medical scale and wall-mounted stadiometer, we measured weight and height to the nearest 0.1 kg and 0.1 cm, respectively. Body mass index (BMI) and BMI percentiles for age and gender were determined using EpiInfo Version 1.1 – 2.0 (CDC, Atlanta, GA). Anthropometric tape measures were used to measure waist and hip circumferences (to the nearest 0.5 cm). All anthropometric data were collected according to the Canadian Standardized Test of Fitness (CSTF) Operations Manual. Ottawa: Government of Canada, Fitness, and Amateur Sport, 1986).

Assessment of Fundamental Movement Skills

There are six fundamental motor skills that were evaluated: run, vertical jump, catch, overhand throw, forehand strike, and kick. These fundamental motor skills were evaluated using an 11 item fundamental movement skill test which has been detailed elsewhere [

12]. The assessment of fundamental movement skills was qualitative rather than quantitative because qualitative assessment methods are not influenced by student strength and can identify difficulty executing a fundamental motor skill. Research assistants rated the presence or absence of each of the qualitative components of each of these skills on four out of five trials [

13]. A total of twelve research assistants were used in the study. The impact of involving more than one observer has been rigorously evaluated. The trained observer and the research assistant consistently achieved <4% inter-observer differences. Researchers who participated in the study of inter-observer agreement also participated in a follow-up study, described here.

Assessment of Physical Fitness

The FITNESSGRAM® program was used to measure cardiorespiratory fitness and muscular strength. FITNESSGRAM® is an assessment and promotion tool developed by the Cooper Institute. It has been the recommended assessment tool and promotion tool for the American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance (AAHPERD) and the required assessment for the state of California and many other states and districts. FITNESSGRAM® has gained widespread support and adoption, largely due to its sound scientific basis [

14,

15]. The participants were asked to perform various fitness tests, including pushing themselves up 90 degrees, curling up for abdominal strength, sitting and reaching for flexibility, and running a mile for cardiovascular fitness.

Assessment of Ethnicity

Based on the self-reported questionnaires parents completed prior to inclusion in the intervention, the ethnicity of the children was determined. If the children were not of Hispanic origin, they were categorized into the non-Hispanic white group. Children who were of Hispanic origin were only included in the study if both parents and grandparent were Hispanic. By doing so, a more accurate picture of the fundamental differences in movement skills between Hispanic and non-Hispanic white elementary school children could be portrayed.

Statistical analysis

All data were checked for normality prior to statistical analysis. T-tests or Mann Whitney U tests were used to assess differences in fitness and fundamental variables between Hispanic and non-Hispanic white elementary school children. The characteristics of Hispanic and non-Hispanic white were compared using the p-value to detect statistical differences in anthropometric, FMS, and fitness characteristics. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Mac version 24.0) and an alpha of 0.05 for all statistics.

3. Results

Anthropometric Measurements

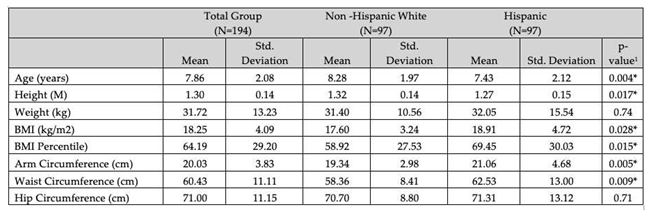

There were no significant group differences across the participants in weight and Hip circumference. There were significant group differences across the participants in age, height, BMI, BMI percentile, arm circumference, and waist circumference.

Table 1 presents the anthropometric outcomes for the evaluable participants.

Fundamental Movement Skills Variables

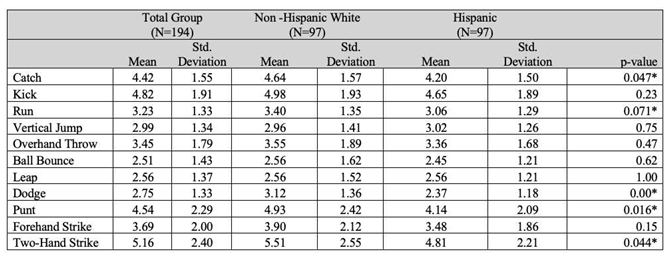

Table 2 presents the movement skills outcomes for the evaluable participants. There were significant differences between Hispanic and Non-Hispanic white across the groups in catch, run, dodge, punt, and two-hand strike (all p’s <0.05). There were no significant differences across the groups in kick, vertical jump, overhand throw, ball bounce, leap, and forehand strike (all p’s >0.05).

3.3. Physical Fitness Variables

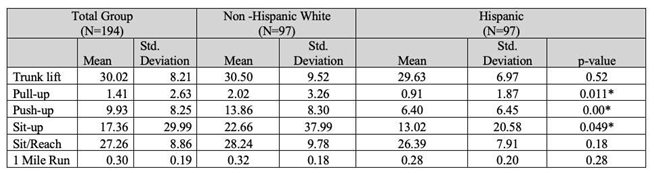

Physical Fitness outcomes for the valuable participants are presented in

Table 3. There were significant differences between Hispanic and Non-Hispanic white across the groups in pull-up, push-up, and sit-up (all p’s <0.05). There were no significant differences between Hispanic and Non-Hispanic white across the groups in the trunk lift, sit/reach, and 1 mile run (all p’s >0.05).

4. Discussion

The results of this study indicate that among Hispanic and non-Hispanic white elementary school children there are several key differences to emphasize. The result of the study demonstrates differences in obesity, FMS, and fitness between both ethnicities, with Hispanic elementary kids being larger, less FMS, and less fit when compared with non-Hispanic white children. FMS has been associated with predicting subsequent obesity from childhood to adulthood [

16]. Therefore, it is important to develop these skills at a young age, as FMS provide an underlying support for successful participation in physical activities and sports throughout your life. Accordingly, preschool children with higher FMS competence are likely to have higher levels of physical fitness and activity as adults [

17]. In addition, movement professionals must also have a broad understanding of the FMS development of Hispanic children [

18]. With the expanding Hispanic population, as well as those health risks, there is a high rate of sedentary behaviors and health risks associated with the Hispanic population [

19]. Consequently, children from low-income and ethnic minority backgrounds are at greater risk of developmental delays. Accordingly, in Hispanic communities, the opportunities for promoting physical activity and reducing sedentary activities differ due to their different family and neighborhood backgrounds [

20].

The findings of the study suggest that object-control skills such as catching, two hand strike, and punting made a big difference whether or not the children were able to perform physical activity tasks such as pull-ups, push-ups, and sit ups. According to previous research, higher levels of proficiency in object-control skills are associated with higher levels of physical activity [

21]. This shows that the results of the object-control skills among the Hispanic and non-Hispanic white children played an important role if they were able to perform well on fitness tests. Similarly, a more recent study found that object control skills predicted physical activity in both ethnic groups more strongly than all other sociodemographic factors put together [

22]. Thus, the development of object control skills for physical activity promotion would also benefit young children.

Moreover, an interesting finding of the study was that there was a significant difference among Hispanic and non-Hispanic White in the FMS of running but there was not a significant difference when it came down to the fitness test of the 1 mile run. In similar research, previous results suggested that locomotor skills competency may be significantly associated with non-Hispanic children's physical activity, but not with Hispanic children's activity [

22]. Subsequently, this corresponds to the results portrayed here by displaying conflicting reports with locomotor skills among the children. Moreover, the findings of the study coincide with other research that proposes FMS and physical activity being related to each other in early school years regardless of sociodemographic background [

23]. This shows that FMS and physical activity are significantly correlated among the children and may provide insight into what the children lack when it comes to FMS. Furthermore, several recent studies indicate that once developed, FMS is likely to carry on throughout childhood and adolescence [

22].

An important strength of this study is the relatively large number of randomly selected children who are representative of the general Moorpark population for this age group. Additionally, this study emphasized only using objective measures; whereas the existing literature has shown that only a few large studies have included objective measures of movement skills and physical fitness. Furthermore, several previous studies have reported benefits from interventions based on subjective outcomes, but this is probably due to a bias in the report of event by subjects and parents. One potential limitation of the study was the absence of data on what the participants among Hispanics and non-Hispanic White did outside of school hours. This may have accounted for the increases in motor skill and fitness level in the control group. In addition, obesity status was measured using BMI, a more accurate measure is needed to get a better depiction of anthropometric measurements.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, future studies should focus on decreasing obesity, increasing fitness, and FMS in Hispanic children. Furthermore, this study attempted to understand young children's FMS and the relationship between physical activity fitness among Hispanic and non-Hispanic White children. More research is needed to investigate the epidemic of childhood obesity. Specifically, in Hispanic children, and the impact that it has on their FMS from such a young age, which results in implications for Hispanic children in the future regarding their physical fitness and health issues [

20]. Accordingly, physical activity and obesity interventions should target young Hispanic children, and intervention strategies should take socioeconomic status into account [

20]. Future interventions aimed at reducing FMS, physical activity, and obesity in Hispanic as well as non-Hispanic young children can be informed by these study’s findings.

Author Contributions

Dr. Kelly had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses. Study concept and design: Dr. Kelly. Acquisition of data: Kelly. Analysis and interpretation of data: Dr. Kelly and Morales. Drafting of the manuscript: All authors contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Dr. Kelly and Morales. Statistical analysis: Dr. Kelly. Obtaining funding: N/A. Administrative, technical, or material support: Morales. Study supervision: Dr. Kelly.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of California Lutheran University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent and child assent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon written request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants and their parents/legal guardian for participating in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ogden, C.L.; Carroll, M.D.; Kit, B.K.; Flegal, K.M. Prevalence of Childhood and Adult Obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2014, 311, 806–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.M.; Parker, L.; Lamont, D.; Craft, A.W. Implications of childhood obesity for adult health: findings from thousand families cohort study. BMJ 2001, 323, 1280–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friel, C. P., Duran, A. T., Shechter, A., & Diaz, K. M. (2020). U.S. Children Meeting Physical Activity, Screen Time, and Sleep Guidelines. American journal of preventive medicine, 59(4), 513–521. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Brooke, Stephanie McLennan, Kasha Latimer, David Graham, Janine Gilmore, Elaine Rush. (2013). Improvement of fundamental movement skills through support and mentorship of classroom teachers, Obesity Research & Clinical Practice, 7(3), 230-234. [CrossRef]

- Dawson-McClure, S., Brotman, L. M., Theise, R., Palamar, J. J., Kamboukos, D., Barajas, R. G., & Calzada, E. J. (2014). Early childhood obesity prevention in low-income, urban communities. Journal of prevention & intervention in the community, 42(2), 152–166.

- Carson, V.; Hunter, S.; Kuzik, N.; Wiebe, S.A.; Spence, J.C.; Friedman, A.; Tremblay, M.S.; Slater, L.; Hinkley, T. Systematic review of physical activity and cognitive development in early childhood. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2015, 19, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Jiang, G.-P.; Ji, Z.-Q.; Pang, B.; Liu, J. Effect of Novel Rhythmic Physical Activities on Fundamental Movement Skills in 3- to 5-Year-Old Children. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutfiyya, M. N., Garcia, R., Dankwa, C. M., Young, T., & Lipsky, M. S. (2008). Overweight and obese prevalence rates in African American and Hispanic children: an analysis of data from the 2003-2004 National Survey of Children's Health. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine : JABFM, 21(3), 191–199. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, K.E.; Morgan, P.J.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Barnett, L.M.; Lubans, D.R. Improvements in fundamental movement skill competency mediate the effect of the SCORES intervention on physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness in children. J. Sports Sci. 2015, 33, 1908–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremer, E.; Cairney, J. Fundamental Movement Skills and Health-Related Outcomes: A Narrative Review of Longitudinal and Intervention Studies Targeting Typically Developing Children. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2016, 12, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, S.W.; Webster, E.K.; Getchell, N.; Pfeiffer, K.A.; Robinson, L.E. Relationship Between Fundamental Motor Skill Competence and Physical Activity During Childhood and Adolescence: A Systematic Review. Kinesiol. Rev. 2015, 4, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallahue, D.L.; Ozmun, J.C.; Goodway, J. Understanding Motor Development: Infants, Children, Adolescents Adults, 7th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Holland. B.V. (1986) Development and validation of an elementary motor performance tests for students classified as non-handicaped, learning disabled or educable mentally impaired. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Michigan State University.

- Shephard, R.J. Curricular Physical Activity and Academic Performance. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 1997, 9, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welk, G. J., Meredith, M.D. (Eds.)( 2008) . Fitnessgram / Activitygram Reference Guide. Dallas, TX: The Cooper Institute.

- Zwiauer, K.F.; Pakosta, R.; Mueller, T.; Widhalm, K. Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Obese Children in Relation to Weight and Body Fat Distribution. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1992, 11, 41S–50S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foweather, L.; Crotti, M.; Foulkes, J.D.; O’dwyer, M.V.; Utesch, T.; Knowles, Z.R.; Fairclough, S.J.; Ridgers, N.D.; Stratton, G. Foundational Movement Skills and Play Behaviors during Recess among Preschool Children: A Compositional Analysis. Children 2021, 8, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pope, M.L.; Liu, T.; Getchell, N. Object-Control Skills in Hispanic Preschool Children Enrolled in Head Start. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2011, 112, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hales, C. M., Carroll, M. D., Fryar, C. D., & Ogden, C. L. (2017). Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS data brief, (288), 1–8.

- Gu, X.; Chen, S.; Zhang, X. Young Hispanic and Non-Hispanic Children’s Fundamental Motor Competence and Physical Activity Behaviors. J. Mot. Learn. Dev. 2019, 7, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, E.S.; Duncan, M.J.; Birch, S.L. Fundamental movement skills and weight status in British primary school children. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2013, 14, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Cohen, K.; Morgan, P.J.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Callister, R.; Lubans, D.R. Fundamental movement skills and physical activity among children living in low-income communities: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 49–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stodden, D.F.; Goodway, J.D.; Langendorfer, S.J.; Roberton, M.A.; Rudisill, M.E.; Garcia, C.; Garcia, L.E. A developmental perspective on the role of motor skill competence in physical activity: An emergent relationship. Quest 2008, 60, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Anthropometric Characteristics of Participants.

Table 1.

Anthropometric Characteristics of Participants.

Table 2.

FMS Characteristics of Participants.

Table 2.

FMS Characteristics of Participants.

Table 3.

Fitness Characteristics of Participants.

Table 3.

Fitness Characteristics of Participants.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).