INTRODUCTION

In the modern world, children’s oral health has great societal and economic meaning. Regardless of the well-known nature of the disease and of the methods of its prevention, dental caries is currently the most prevalent civilization disease impacting most of the world’s population. Research shows that 60–90% of school children have caries, therefore, it represents a public health issue that requires serious consideration (1).

Each individual’s oral health depends on their oral hygiene habits, diet, economic status, and frequency of dental health care visits (2). Caries prevention is based on measures and activities conducted in early childhood which, besides continuous fluoride application, high levels of oral hygiene, and adequate changes in diet and lifestyle, include systemic prevention and health education programs (3,4).

Research on the prevalence of childhood caries conducted in Croatia has been rare and sporadic, however, a trend of decayed, missing, and filled teeth for permanent teeth (DMFT) index decline can be observed; it was measured at 7 in 1968 and at 3,5 in 1999 (5,6). Studies published in 2014 and 2015 reported a 4,8 DMFT index in fifth grade students and a 4,14 decayed, missing, and filled teeth for primary teeth (dmft) index and a 4,18 DMFT (7,8). Study published in 2019 reported a 3,0 DMFT (3). The lack of data and the decline of dental care quality in early childhood age can be traced back to the events of the nineties, when, along with the civil war, a primary care reform took place. This reform eliminated pediatric specialist practices from the national health system, that had previously conducted pediatric dental care and prevention, including the dmft/DMFT index and other oral health indicators. Additionally, during this reform, the choice of the child’s dentist was given to the parents, when previously all kindergartens and schools had specialist practices for child and prevention stomatology (9).

Recent locally conducted studies have shown that oral health in Croatia is still unsatisfactory and neglected, and that the awareness of the importance of oral health and its influence on general health is insufficient (10,11). It is well-known that dental health needs to be addressed from the earliest age since children with healthy primary teeth have a very high likelihood of having healthy permanent dentition (12). The issue of inadequate prevention has been recognized by the experts of the Teaching institute of public health of Primorje-Gorski Kotar County (PGC), Clinic for dental medicine of the Clinical Hospital Centre Rijeka, and the Department of child stomatology of the Faculty of dental medicine of the University of Rijeka, who had implemented the “Advancement of oral health in PGC children and youth” Program which has been conducted continuously since 2008. This has ensured systematic oral health care of children and youth in the PGC. A similar screening program had previously shown the usefulness of early detection of caries and oral health needs through the promotion of early prevention, as well as the importance of public health interventions (13).

The aim of this study was to show the results of the continuous conduction of our Program and the efficiency of this type of model in the improvement of children’s oral health by evaluating the dmft/DMFT indexes from 2008 to 2019.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In the “Advancement of oral health in PGC children and youth” Program we included students enrolling into the first grade of elementary school (average age: 6) and those enrolling in the fifth grade (average age: 12), considering that these are the WHO recommended age groups for monitoring oral health (14). From 2008 to 2019, 21714 first grade and 22708 fifth grade students were assessed, with an 85% response rate for first and 80% for fifth graders. For the purposes of this research, we created a form based on the DMF Klein-Palmer system, on which clearly visible tooth surface cavities were noted as caries, and initial changes in transparency without cavitations were noted as healthy teeth (15).

Students enrolling in the first elementary grade were handed a form at school which had to then be filled out by their chosen dentist. The filled-out form was given to their school medicine doctor as part of the health documentation for school enrollment. Fifth grade students had their teeth examined at school by pediatric dentists. The exams were conducted in classrooms with artificial lighting and single-use mirrors. The same forms were used and educational workshops on oral health conducted. The time of the dental team arrival was agreed upon with the school’s administrative service. Prior to the exams, the school provided the children with written consent forms for the parents. Each examined student received a notice for their parents outlining their oral status, the conducted workshops, and recommendations for oral health maintenance. During the school year, nursing graduates from the teams of School and adolescent medicine conducted one-hour school workshops for all present students on the importance of oral health maintenance and adequate teeth brushing with demonstrations. Each student was then also presented with a “For a healthy and pretty smile” brochure.

From 2008 to 2019, 1240 workshops were conducted in the first grades and 21714 students were assessed, and 1015 workshops were conducted with 22708 students assessed in the fifth grades. Since the Program’s inception, health visitors educated pregnant and postpartal women on the importance of oral health and handed them with “The health and smile of your children are in your hands” educational brochures, thus educating 26559 women.

Since 2014, the Program has been implemented in PGC kindergartens as well; more intensive preventive oral health workshops were included alongside other daily activities. In the kindergartens with adequate conditions, supervised teeth brushing was organized for children aged 3–6. The Program is currently being conducted in 90 kindergartens in the PGC area; 98% of kindergartens have adequate conditions and conduct teeth brushing once a day. During the observed period, 2336 workshops were conducted, including 30496 preschool children. After the workshops, the parents were presented with educational “Care for children’s teeth” brochures and the children with educational coloring books. Additionally, the parents received instructions upon kindergarten enrollment regarding the need to choose their child’s dentist.

Statistical analysis

The form data were transferred into a previously formatted Microsoft Office Excel table and analyzed in MedCalc, version 19.1.7 (MedCalc Software Ltd, Ostend, Belgium). The age of the included participants is shown as median and range (min-max). Categorical data are shown through absolute and relative frequencies. The differences between frequencies have been calculated with a Chi-square test, and as a post hoc analysis, the proportion t-test was used. The trend was calculated using the Chi-square test for trend.

Variance analysis (ANOVA) was used to determine the difference between dmft/DMFT indexes by age and sex, whereas the Scheffé test was used as a post hoc analysis. Significance level was set at P<0.05 for all analyses.

RESULTS

From 2008 to 2019, 44422 children in PGC were examined; 21714 first grade students, median age 6 (range: 5–9) and 22708 fifth grade students, median age 12 (10–15). The total coverage through the entire study period was 83%. Due to incomplete sex data, the data from

Table 1 were used in analyses that considered sex.

Table 1 shows the sex distribution of the included participants. There was no statistically significant difference between boys and girls (P=0,204).

Table 2 shows the measures of central tendency for the dmft index of first graders by years and the significant dmft differences by research years. The trend test showed that there was a statistically significant difference between groups in a certain direction (χ=334,15, P<0,001), i.e., that the dmft index diminished over time.

Using the variance analysis, it was found that there was a significant difference in the dmft indexes (F[11, 21702]=9,75, P<0,001) and by using the post hoc Scheffé test it was found that the dmft index was greater in the first years of research compared to the final years, as shown in

Table 2.

The means, standard deviations, and ranges of the DMFT indexes of fifth grade students are shown in

Table 3.

The differences between the dmft indexes of first grade students and the DMFT indexes of the fifth grade students were also calculated and are shown in

Table 4.

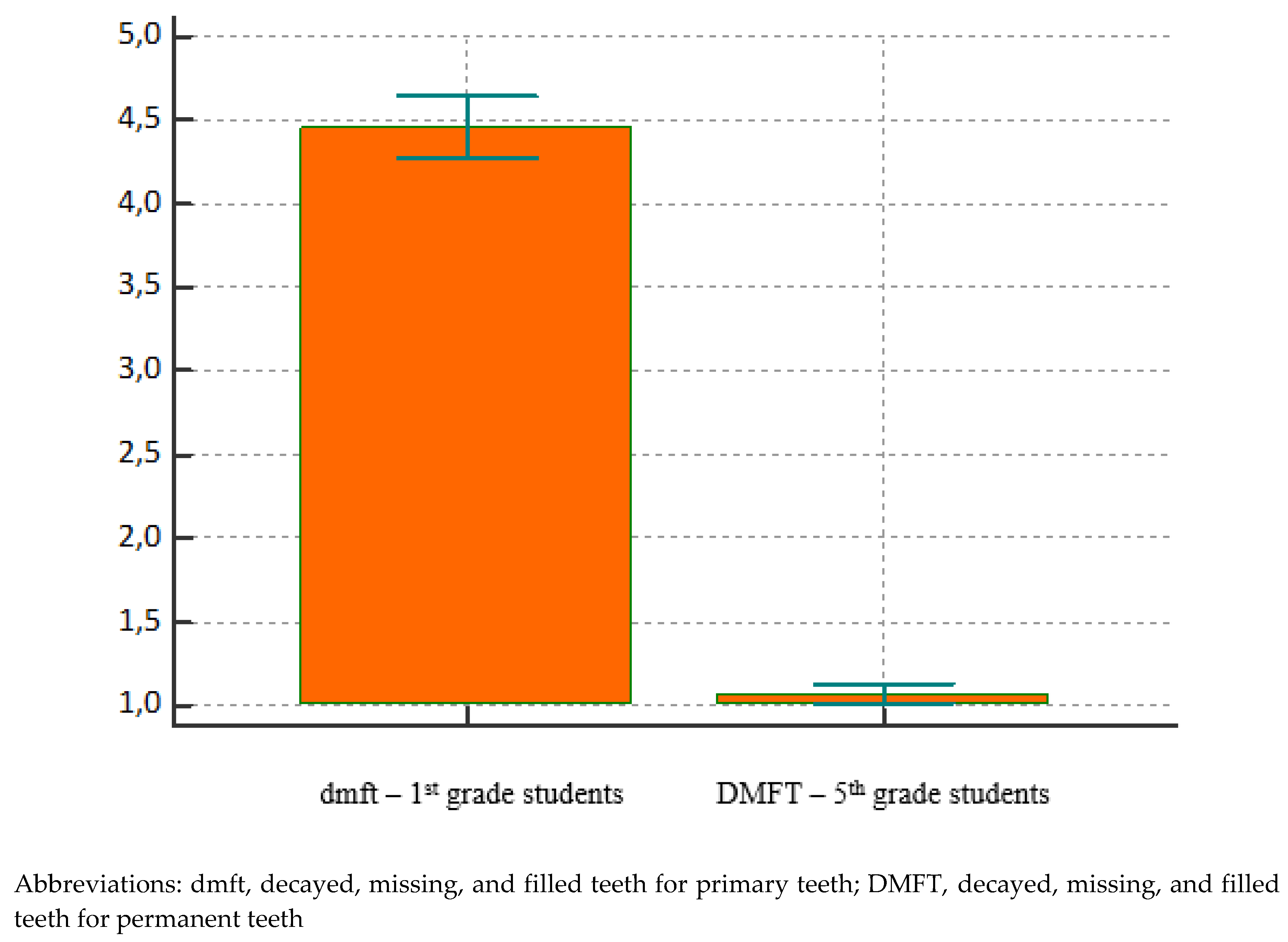

The t-test showed that the first grade students had a significantly higher dmft than the fifth grade DMFT (P<0,01) (

Figure 1).

The oral health indicator for the first grade children, dmft, declined from 4,66 to 3,73 and that for the fifth grader students, DMFT, from 2,50 to 1,00.

With the two-way ANOVA analysis, we found a statistically significant difference by sex, with girls having a lower dmft (F[3,41624]=5502, P<0,001) and a lower DMFT (F[3,41624]=5805, P<0,001) than boys.

We found an increasing trend in the number of insured persons using pediatric dental health care since birth until 6 years of age (χ=137,27; P<0,001) (

Table 5).

From the total number of kindergarten-age preschool children (3–6 years old) in the PGC (N=5693 children) which were included in the Program, we found that 50% brushed their teeth daily.

DISCUSSION

From the data obtained during the Program according to our above prevention an oral health maintenance model, in the PGC first grade students the dmft index decreased from 4,66 to 3,73, whereas the DMFT index in fifth grade students decreased from 2,50 to 1,00 which is below the WHO recommended value of 1,5 (15). From 2011 to 2015, the dmft index in first grade students was continuously within the 4,23–4,17 range. With the Program expansion in 2014 and the commencement of continuous, comprehensive, and systematic conduction of prevention activities in preschool institutions, an improvement of oral health indicators was seen in first graders – the dmft was 4,0 in 2016, 3,8 in 2017 and 2018, and 3,7 in 2017. With this, we have proven that prevention programs that are intensely conducted in preschool establishments and are based on teeth brushing monitoring, have a positive impact on the dental health of elementary school children (16,17). Although a drop in the dmft index is present, it is necessary to continue to work on prevention and oral health improvement in first grade students to reach the WHO-recommended 1,5 value (15). Additionally, the obtained results show an improvement in oral health status, i.e., a reduction in the DMFT index, in fifth grade PGC students as well; as such, we can compare ourselves with other countries with a low DMFT index, such as Italy (1,1), Spain (1,07), Sweden (1,1), and Denmark and Switzerland (0,9) (18). The obtained value in fifth grade students demonstrates the effectiveness and importance of conducting programs in schools (dental exams and educational workshops), seeing as this type of constant oral health monitoring is more effective than the classic model of dental health care (17,19). The results of a 2022 meta-analysis showed that there have been few studies on oral hygiene education worldwide; from the 18 in total, only two have been conducted in Europe, both with different activities and time spent in working with children, and only three have been conducted in line with the WHO-outlined concept, which gives additional significance to the quality of our Program considering the results we obtained (17). Aside from working with children, the Program also motivates the parents to choose a dentist as soon as possible. Seeing that Croatia does not have organized oral health care for children, this responsibility is left to the parents, who oftentimes do not choose a dentist until the manifestation of caries-related issues (pain, abscess, et.). We ensured that most children enrolling in the first grade have a chosen dentist, which was not the case prior. By choosing a dentist, the child is included in the dental health care system, thus changing the practice of dentists only being visited in dire need and imposing the option of preventive exams. Our model of having dentists visit schools has proven beneficial, similarly to several studies which have shown that children included in school dental care programs are more motivated to visit their dentist and are more regular in their checkups and dental health care procedures (20,21).

The number of preventive dentist exams has increased with time since the Program inception, especially after the introduction of preschool activities in 2014. Our prevention activities have also increased the parent’s awareness of the need to visit their dentist early, which is visible in the increasing trend of the numbers of insured persons under the age of 6. Good cooperation has been established between School and adolescent medicine doctors and nursing graduates in their teams, which additionally motivated and educated parents on the oral health of their children, distributed flyers, and encouraged them to choose dentists as soon as possible. The public health system’s School and adolescent medicine conducts prevention and specific and health-education pediatric healthcare measures, and its good organization is the basis for the conduction of pediatric dental prevention programs (22). In the conduction of the Program, health visitors were also included, educating pregnant and postpartal women on the importance of oral health maintenance. Pregnant women are especially motivated for maintaining the health of their children, therefore we recommend that all preventive activities, including those pertaining to oral health, are commenced during pregnancy. Additionally, mothers have a strong influence on their children’s future habits (23). Being that in the early Program years, the DMFT index declined with time and the dmft remained the same, it was necessary to commence more intensive prevention activities by aiming health care at preschool children. Besides the supervised teeth brushing, the educational workshops had a great influence in creating healthy habits, and the role of nurses (health supervisors in kindergartens) in promoting oral health has been very significant as well (24). Therefore, in 2014, we conducted workshops more intensively with preschool children in kindergartens and included pediatricians in 2019 to cover all preschool children. The aim was that pediatricians, by following international, European, and Croatian guidelines, would send the children on their first dental check-up between 6–12 months of age (25).

An early first visit to the dentist is important in educating the parents on oral hygiene and proper feeding. Here, pediatric dentists have an important role, as well as pediatricians who need to promote an early first dentist visit in order to commence caries prevention in early childhood (26).

The Program showed an improvement in children’s oral health (dmft and DMFT index reduction), as well as its modifiability for obtaining even better results in the future. Various stakeholders are important in the conduction of our Program, each acting directly or indirectly within their domain in order to achieve a common goal, i.e., the good oral health of children. Through their mobilization and interconnection, additional financial strains on the system can be avoided (27). Dental health care needs to be refocused from curative to preventive (28). In Croatia, there is a problem of pediatric oral care organization, which has lost its importance during the last 15 years of reforms (29).

In light of such an unsatisfactory level of prevention, especially in children, it is necessary to consider how it can be improved. Preventive activities need to be strengthened in order to make oral health care an important part of health education. Here, we can use Denmark as an example, as it has an overreaching dental health care until 18 years of age. By creating local clinical establishments, free healthcare is provided that includes education and organized invitations to parents along with response monitoring (30).

Our model has proven sustainable as it has been in place for over a decade and has demonstrable improvements in children’s oral health, as well as being flexible to adaptation and improvement.

CONCLUSIONS

Considering the possibilities of caries prevention and the advantages of early caries lesion diagnostics, it is necessary to establish preventive activities in kindergartens and schools.

Conducting these types of programs has great importance in stimulating children and parents to visit their health care doctors. Education on adequate oral hygiene, dietary habits, and oral disease prevention enables children to develop lifelong habits of maintaining their oral health along with their overall health.

With the continuation of such activities, it is necessary to work on reintegrating specialists of child and preventive stomatology into primary health care.

Conflicts of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Selwitz RH, Ismail AI, Pitts NB. Dental caries. Lancet 2007;369:51–9. [CrossRef]

- Pellizzer C, Pejda S, Špalj S, Plančak D. Unrealistic Optimism and Demographic Influence on Oral Health-Related Behaviour and Perception in Adolescents in Croatia. Acta Stomatologica Croat 2007;41:205–15.

- Lešić S, Dukić W, Šapro Kriste Z, Tomičić V, Kadić S. Caries prevalence among schoolchildren in urban and rural Croatia. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2019;27(3):256-262. [CrossRef]

- Petersen PE. Changing oral health profiles of children in Central and Eastern Europe- Challenges for 21st century. IC Digest 2003;2:12–3.

- Rajić Z, Radionov D, Rajić-Mestrović S. Trends in dental caries in 12-year old children in Croatia. Coll Antropol 2000;24:21–4.

- Ivančić Jokić N, Bakarčić D, Janković S, Malatestinić G, Dabo J, Majstorović M, et al. Dental caries experience in Croatian school children in Primorsko-goranska county. Cent Eur J Public Health 2013;21:39–42. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization: Available from: https://capp.mau.se/country-areas/croatia/.

- Radić M, Benjak T, Dečković Vukres V, Rotim Ž, Filipović Zore I. Presentation of DMFT/dmft Index in Croatia and Europe. Acta Stomatol Croat 2015;49:275–84. [CrossRef]

- Rajić Z. Preventive dental medicine in Croatia-yesterday, today, tomorrow. Medix 1997;13:16–7.

- Ivić-Kardum M. Prevalence of Progressive Periodontal Disease in the Population of Zagreb. Acta Stomatologica Croat 2000;34:149–56.

- Ivica A, Galić N. Attitude towards Oral Health at Various Colleges of the University of Zagreb: A Pilot Study. Acta Stomatologica Croat 2014;48:140–6.

- Outline of the strategic plan for oral health care and promotion 2013–2015. Zagreb; Ministry of Health of the Republic of Croatia. Committee for the protection and promotion of oral health care, 2013.

- Locker D, Frosina C, Murray H, Wiebe D, Wiebe P. Identifying children with dental care needs: evaluation of a targeted school-based dental screening program. J Public Health Dent 2004;64:63–70. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization: Oral Health Surveys-Basic Methods. 5th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

- Asvall, JE. The Health for All Policy Framework for the Who European Region. European Health for All Series, No.6; WHO, Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1998;11–34.

- Winter J, Jablonski-Momeni A, Ladda A, Pieper K. Effect of supervised brushing with fluoride gel during primary school, taking into account the group prevention schedule in kindergarten. Clin Oral Investig 2017;21:2101–7. [CrossRef]

- Akera P, Kennedy SE, Lingam R, Obwolo MJ, Schutte AE, Richmond R. Effectiveness of primary school-based interventions in improving oral health of children in low-and-middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 2022;2:264. [CrossRef]

- Bratthall D. Introducing the Significant Caries Index together with a proposal for a new global oral health goal 12-year-olds. Int Dent J 2000;50:378–84. [CrossRef]

- Bundy DAP, Schultz L, Sarr B, Banham L, Colenso P, Drake L. The School as a Platform for Addressing Health in Middle Childhood and Adolescence In: Bundy DAP, de Silva N, Horton S, Jamison DT, Patton GC - editors. Child and Adolescent Health and Development. Vol.8. 3rd ed. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank; Washington DC, 2017; p. 269–85.

- Nguyen TM, Hsueh YS, Morgan MV, Marino RJ, Koshy S. Economic Evaluation of a Pilot School-Based Dental Checkup Program. JDR Clin Trans Res 2017;2:214–22. [CrossRef]

- Praaveen G, Anjum MS, Reddy PP, Monica M, Rao KY, Begum MZ. Effectiveness of school dental screening on stimulating dental attendance rates in Vikarabad town: A randomized controlled trial. J Indian Assoc Public Health Dent 2014;12:70–3.

- Pavić Šimetin I, Radić Vuleta M, Jurić H, Kvesić Jurišić A, Malenica A. Program for Dental Health Advancement in Children „Dental Passport“. Acta Stomatologica Croat 2020;54:121–9. [CrossRef]

- Desai J, Varkey IM, Lad D, Ghule KD, Mathew R, Gomes S. Knowledge and Attitude about Infant Oral Health: A Paradox among Pregnant Women. J Contemp Dent Pract 2022;23:89–94. [CrossRef]

- de Siguera Sigaud CH, Dos Santos BR, Costa P, Toriyama ATM. Promoting oral care in the preschool child: effects of a playful learning intervention. Rev Bras Enferm 2017;70:519–25. [CrossRef]

- Ivančić Jokić N, Bakarčić D, Katalinić A, Ferreri S, Mady B. Early childhood caries (baby bottle caries). Medicina 2006;42:282–5.

- Škrinjarić I, Čuković-Bagić I, Goršeta K, Verzak Ž. Child oral health - the role of paediatric dentists and paediatricians in early prevention of oral diseases. Paediatr Croat 2010;54:131–8.

- Fraihat N, Madae'en S, Bencze Z, Herczeg A, Varga O. Clinical Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Oral-Health Promotion in Dental Caries Prevention among Children: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public health 2019;16:2668. [CrossRef]

- Cappelli DP, Mobley CC. Prevention in clinical oral health care. St. Louis: (MO) Mosby Elsevier, 2008.

- Croatian Dental Chamber. Strategy of dental care development 2009–2015, Zagreb: Croatian Dental Chamber, 2009.

- Platform for better oral health in Europe. The State of Oral Health in Europe; 2012. The State of Oral Health in Europe Report. Available from: http://www.oralhealthplatform.eu/our-work/the-state-of-oral-health-in-europe/; accessed 19 September 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).