Submitted:

03 October 2023

Posted:

05 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

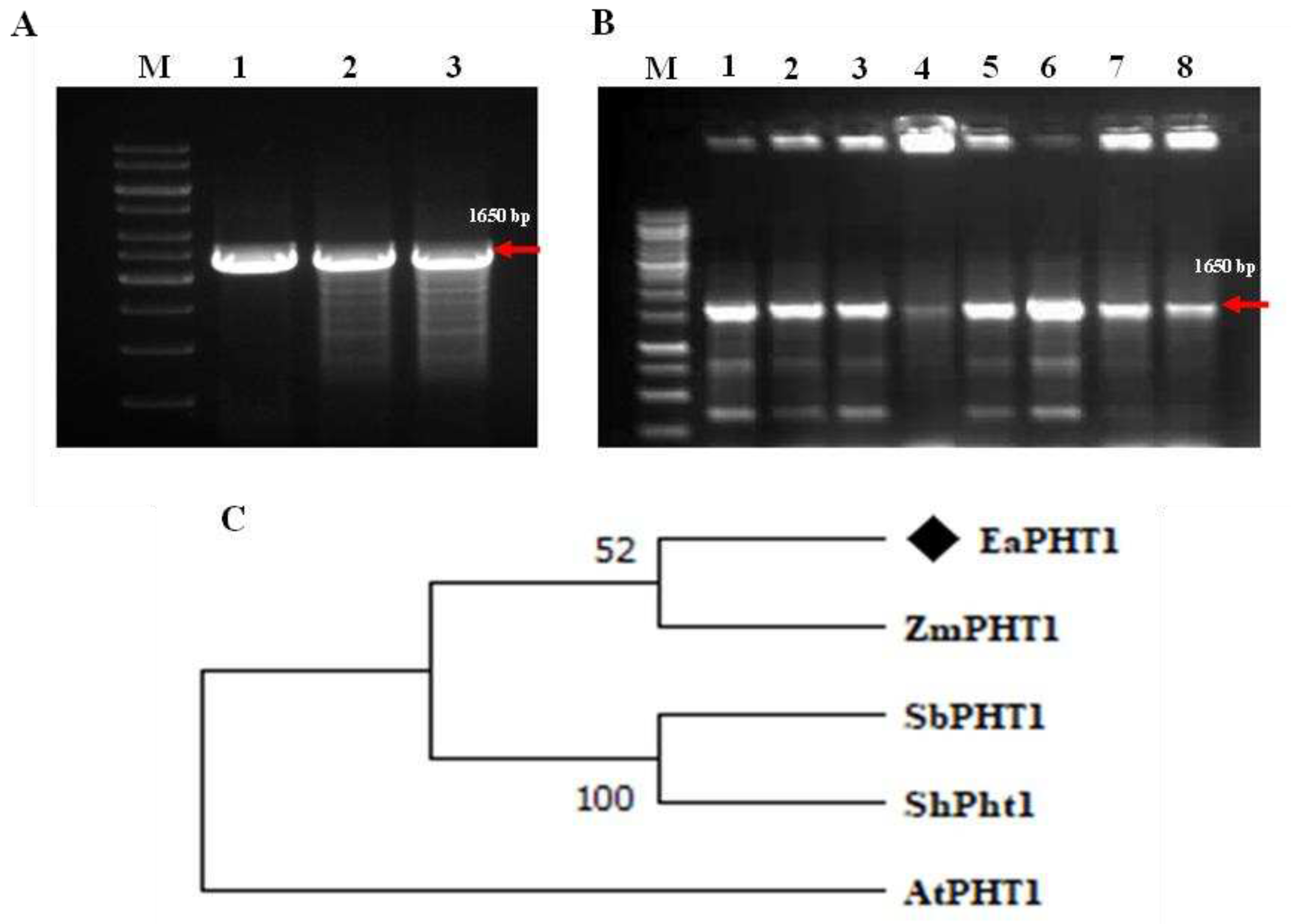

2.1. Isolation and sequence analysis of EaPHT1;2 gene from E. arundinaceus

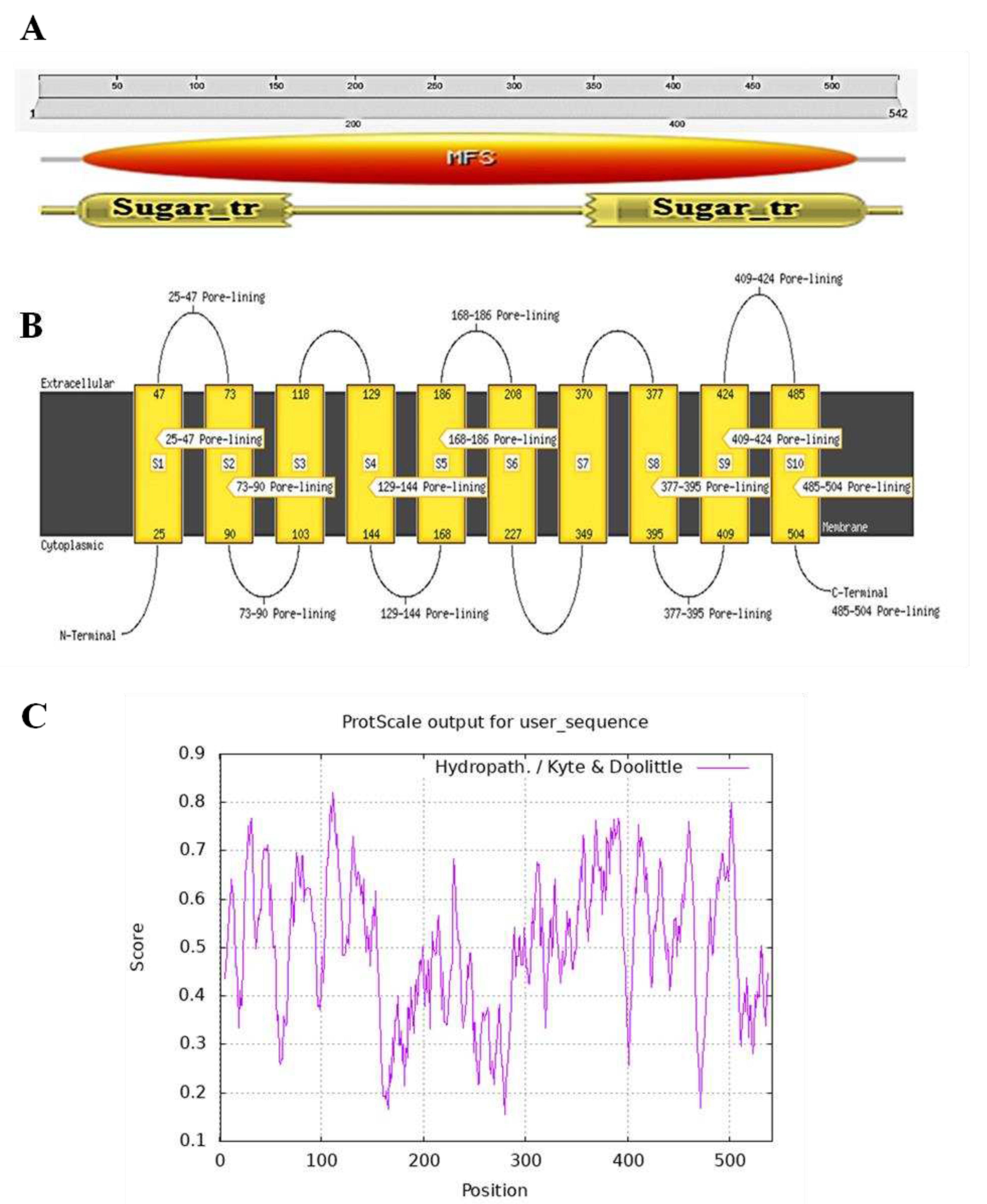

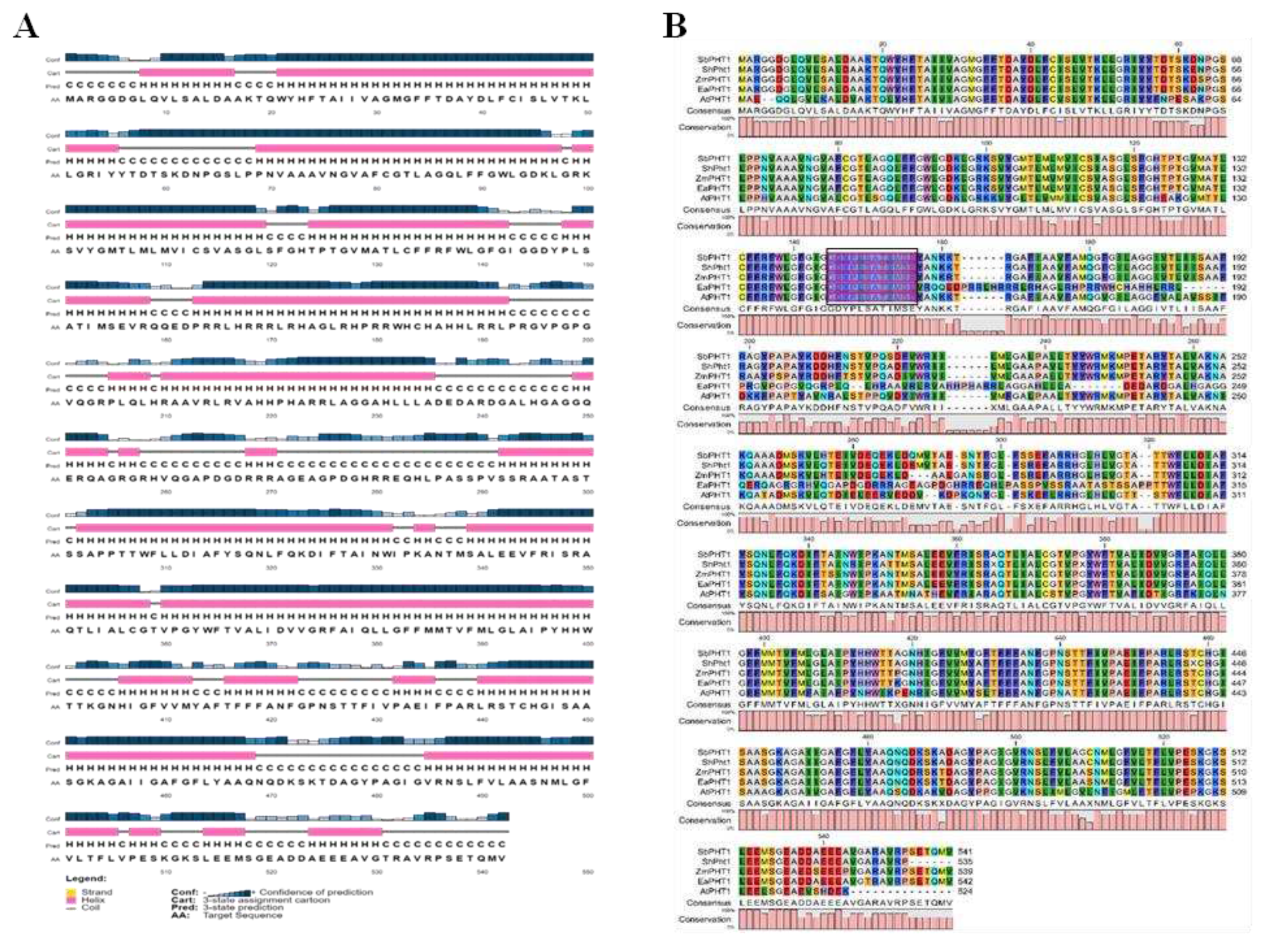

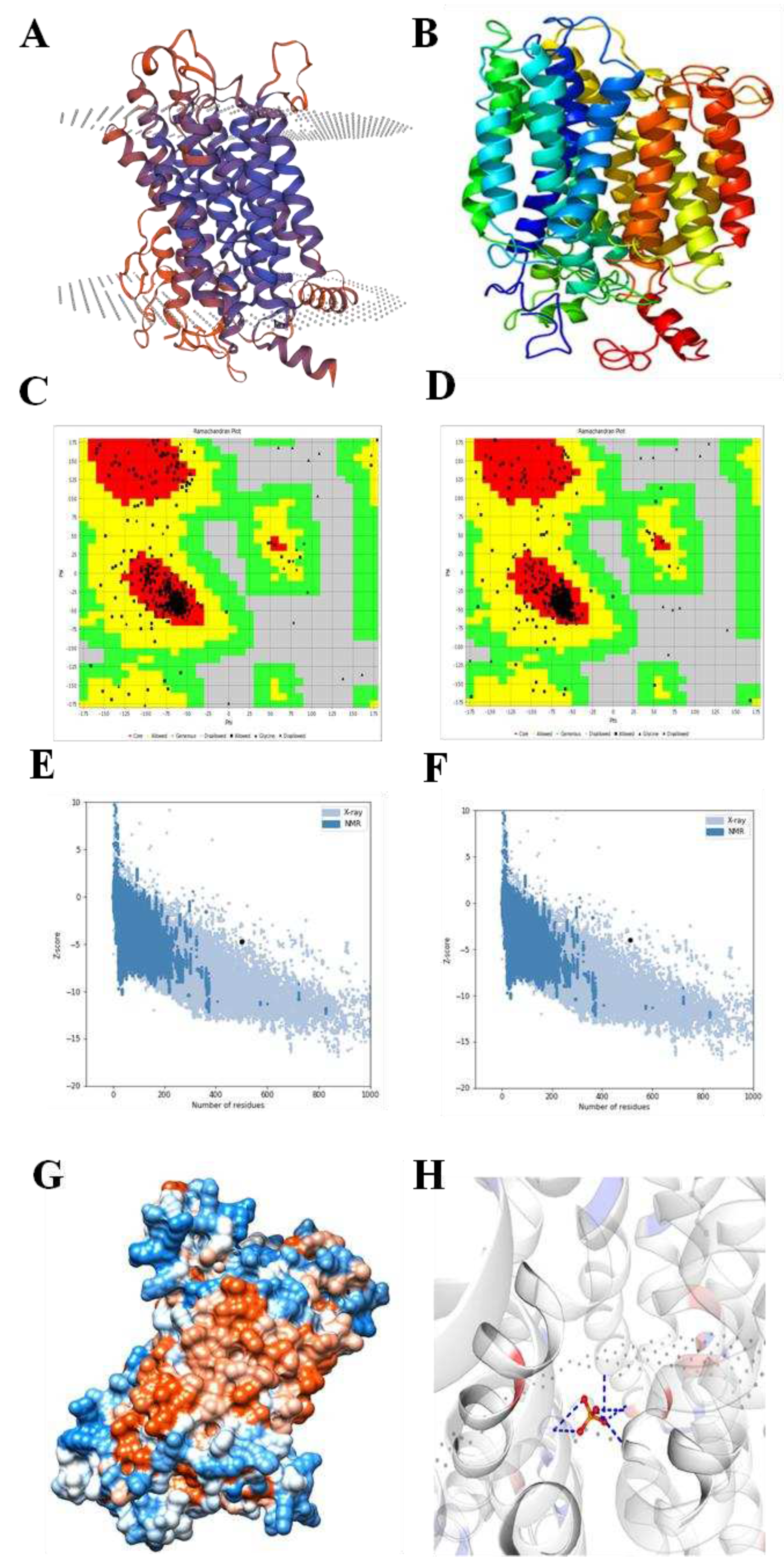

2.2. Structural prediction of EaPHT1;2 protein

2.3. Protein association network and subcellular localization of analysis

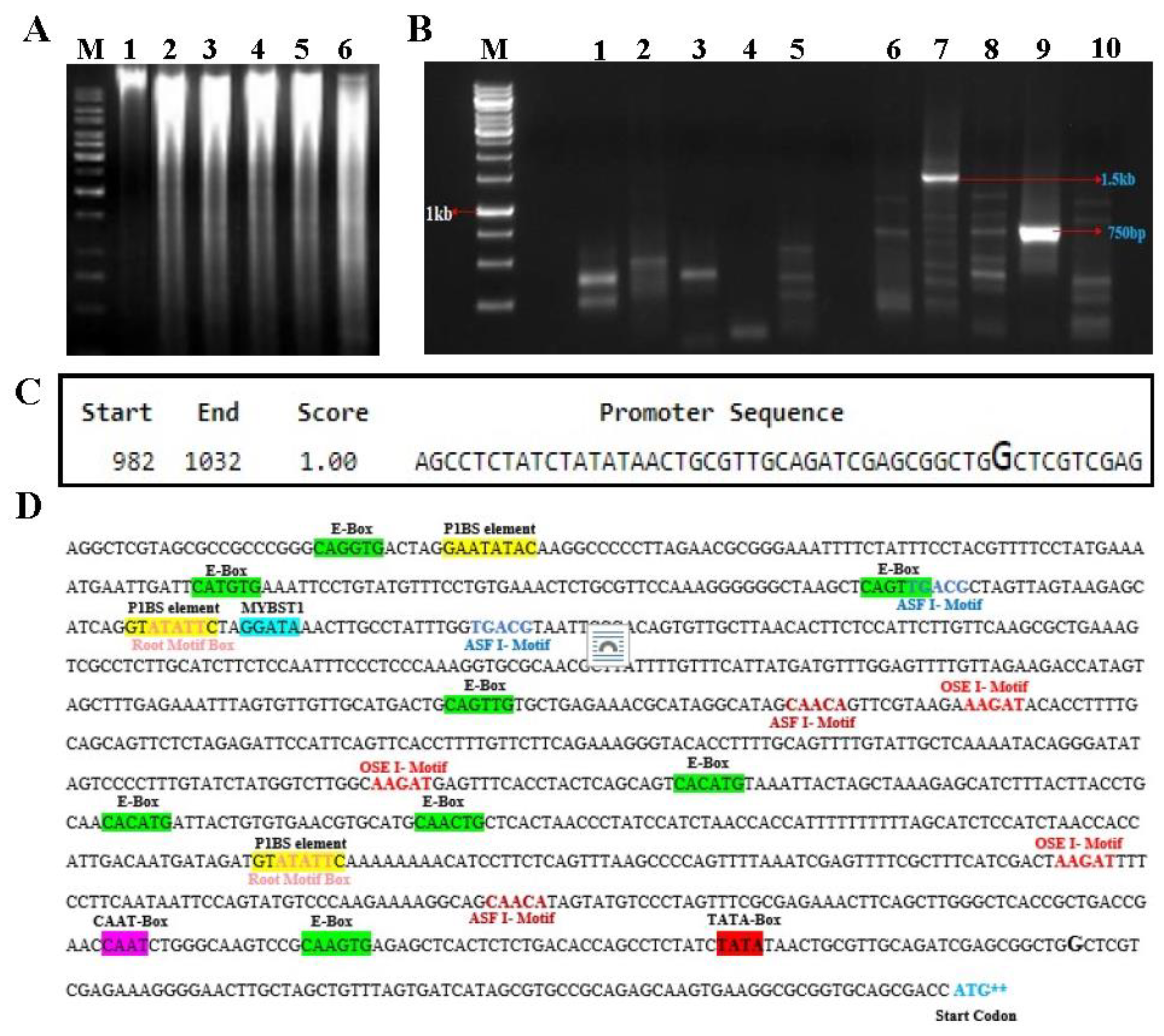

2.4. Isolation of PHT1 promoter region using a genome walking method

2.5. In-silico analysis of Promoter

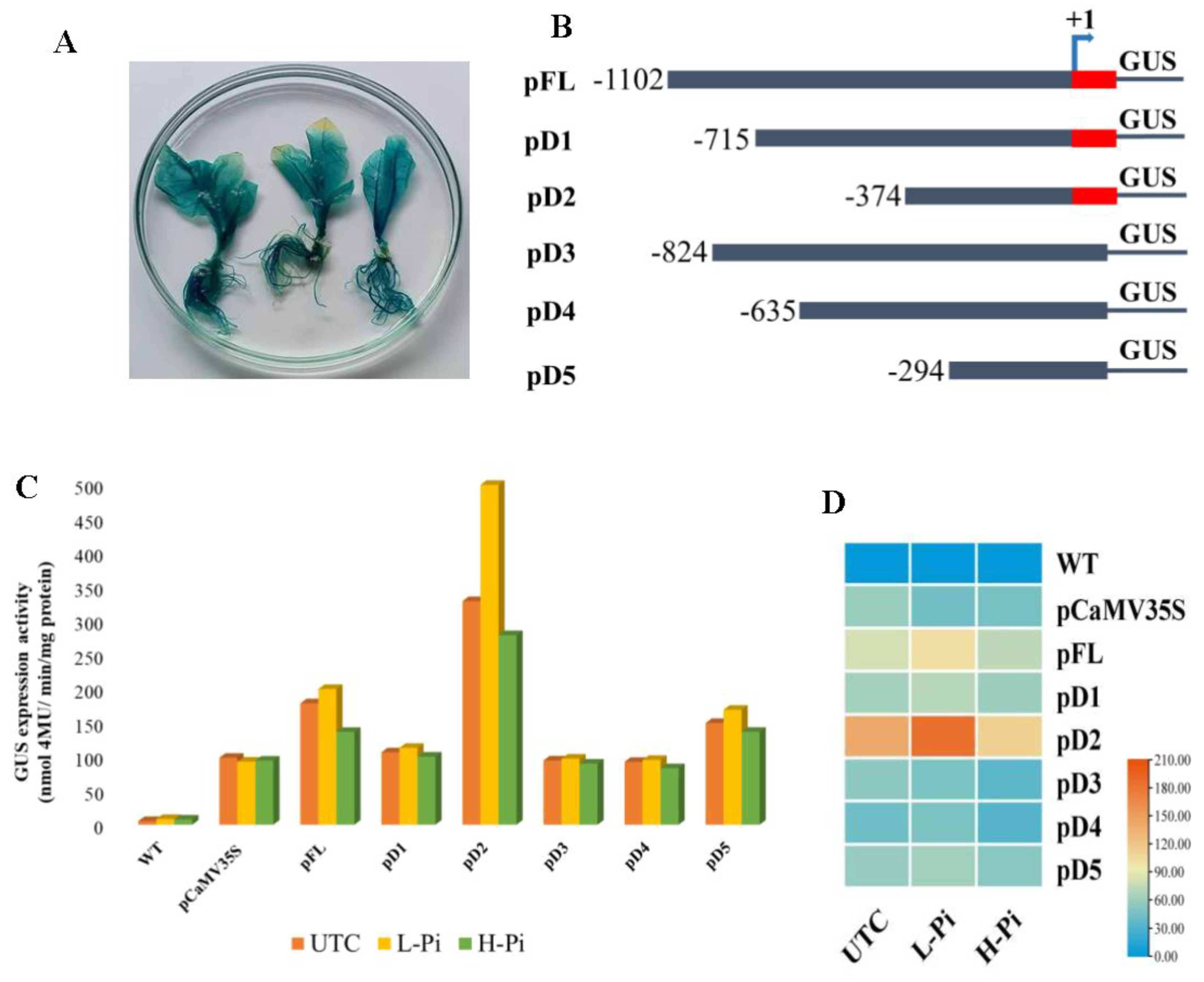

2.6. Expression analysis of EaPHT1;2 promoters in tobacco transgenic events

2.7. EaPHT1;2 promoter activity in Pi stress

2.8. Relative GUS expression analysis of EaPHT1;2 promoter using RT-PCR

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacteria and Plant Material

4.2. EaPHT1;2 Gene isolation and cloning

4.3. Bioinformatics characterization of EaPHT1;2 gene

4.4. Isolation of EaPHT1;2 promoter region using a genome walking method

4.5. Bioinformatics analysis of the promoter regions

4.6. Vector Construction and Tobacco Transformation

4.7. Low and High -Pi Treatments

4.8. Histochemical and Fluorimetric β-glucuronidase (GUS) assays

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gu, M.; Chen, A.; Sun, S.; Xu, G. Complex Regulation of Plant Phosphate Transporters and the Gap between Molecular Mechanisms and Practical Application: What Is Missing? Molecular Plant 2016, 9, 396–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Upadhyay, M.K.; Srivastava, A.K.; Abdelrahman, M.; Suprasanna, P.; Tran, L.-S.P. Cellular and Subcellular Phosphate Transport Machinery in Plants. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19, 1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Lu, H.; Liu, Y.; Mao, C. Phosphate Uptake and Transport in Plants: An Elaborate Regulatory System. Plant and Cell Physiology 2021, 62, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crombez, H.; Motte, H.; Beeckman, T. Tackling Plant Phosphate Starvation by the Roots. Developmental Cell 2019, 48, 599–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilaça De Vasconcelos, M.J.; Fontes Figueiredo, J.E.; De Oliveira, M.F.; Schaffert, R.E.; Raghothama, K.G. PLANT PHOSPHORUS USE EFFICIENCY IN ACID TROPICAL SOIL. RBMS 2022, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balemi, T.; Negisho, K. Management of Soil Phosphorus and Plant Adaptation Mechanisms to Phosphorus Stress for Sustainable Crop Production: A Review. Journal of soil science and plant nutrition 2012, 12, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpinar, B.A.; Avsar, B.; Lucas, S.J.; Budak, H. Plant Abiotic Stress Signaling. Plant Signal Behav 2012, 7, 1450–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachdev, S.; Ansari, S.A.; Ansari, M.I.; Fujita, M.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Abiotic Stress and Reactive Oxygen Species: Generation, Signaling, and Defense Mechanisms. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satheesh, V.; Tahir, A.; Li, J.; Lei, M. Plant Phosphate Nutrition: Sensing the Stress. Stress Biology 2022, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Keitel, C.; Dijkstra, F.A. Global Analysis of Phosphorus Fertilizer Use Efficiency in Cereal Crops. Global Food Security 2021, 29, 100545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbasiouny, H.; El-Ramady, H.; Elbehiry, F.; Rajput, V.D.; Minkina, T.; Mandzhieva, S. Plant Nutrition under Climate Change and Soil Carbon Sequestration. Sustainability 2022, 14, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechtaoui, N.; Rabiu, M.K.; Raklami, A.; Oufdou, K.; Hafidi, M.; Jemo, M. Phosphate-Dependent Regulation of Growth and Stresses Management in Plants. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussaume, L.; Kanno, S.; Javot, H.; Marin, E.; Nakanishi, T.M.; Thibaud, M.-C. Phosphate Import in Plants: Focus on the PHT1 Transporters. Frontiers in Plant Science 2011, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, L.; Yu, D.; Xu, K.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Wang, P.; Chen, G.; Liu, Z.; Peng, C.; et al. Integrative Analysis of the Wheat PHT1 Gene Family Reveals A Novel Member Involved in Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Phosphate Transport and Immunity. Cells 2019, 8, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rae, A.L.; Cybinski, D.H.; Jarmey, J.M.; Smith, F.W. Characterization of Two Phosphate Transporters from Barley; Evidence for Diverse Function and Kinetic Properties among Members of the Pht1 Family. Plant Mol Biol 2003, 53, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Chang, X.-J.; Ye, Y.; Xie, W.-B.; Wu, P.; Lian, X.-M. Comprehensive Sequence and Whole-Life-Cycle Expression Profile Analysis of the Phosphate Transporter Gene Family in Rice. Molecular Plant 2011, 4, 1105–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, C.; Wang, X.; Hu, R.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, C.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, C.; Fu, Y.-F. The Pattern of Phosphate Transporter 1 Genes Evolutionary Divergence in Glycine maxL. BMC Plant Biol 2013, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceasar, S.A.; Hodge, A.; Baker, A.; Baldwin, S.A. Phosphate Concentration and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Colonisation Influence the Growth, Yield and Expression of Twelve PHT1 Family Phosphate Transporters in Foxtail Millet (Setaria Italica). PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e108459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Liao, D.; Gu, M.; Qu, H.; Sun, S.; Xu, G. Genome-Wide Investigation and Expression Analysis Suggest Diverse Roles and Genetic Redundancy of Pht1 Family Genes in Response to Pi Deficiency in Tomato. BMC Plant Biol 2014, 14, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Meng, S.; Li, M.; Zhao, Z. Genomic Identification and Expression Analysis of the Phosphate Transporter Gene Family in Poplar. Frontiers in Plant Science 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Li, M.; Shao, Y.; Yu, L.; Ma, F. Comprehensive Genomic Identification and Expression Analysis of the Phosphate Transporter (PHT) Gene Family in Apple. Frontiers in Plant Science 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, W.; Zhao, Y.-Y.; Zhao, X.-Q.; He, X.; Ma, W.-Y.; Deng, Y.; Chen, X.-P.; Tong, Y.-P. Genome-Wide Identification, Characterization, and Expression Analysis of PHT1 Phosphate Transporters in Wheat. Frontiers in Plant Science 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Liao, L.; Xu, J.; Liang, X.; Liu, W. Genome-Wide Identification and Functional Characterization of the Phosphate Transporter Gene Family in Sorghum. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Lu, M.; Zhang, C.; Qu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, J.; Yuan, J. Isolation and Functional Characterisation of the PHT1 Gene Encoding a High-Affinity Phosphate Transporter in Camellia Oleifera. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology 2020, 95, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lhamo, D.; Shao, Q.; Tang, R.; Luan, S. Genome-Wide Analysis of the Five Phosphate Transporter Families in Camelina Sativa and Their Expressions in Response to Low-P. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 8365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, S.; An, Y.; Hu, T.; Yang, P. Functional Analysis of the Phosphate Transporter Gene MtPT6 From Medicago Truncatula. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio, V.; Linhares, F.; Solano, R.; Martín, A.C.; Iglesias, J.; Leyva, A.; Paz-Ares, J. A Conserved MYB Transcription Factor Involved in Phosphate Starvation Signaling Both in Vascular Plants and in Unicellular Algae. Genes Dev. 2001, 15, 2122–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Jiao, F.; Wu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; He, X.; Zhong, W.; Wu, P. OsPHR2 Is Involved in Phosphate-Starvation Signaling and Excessive Phosphate Accumulation in Shoots of Plants. Plant Physiology 2008, 146, 1673–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos, R.; Castrillo, G.; Linhares, F.; Puga, M.I.; Rubio, V.; Pérez-Pérez, J.; Solano, R.; Leyva, A.; Paz-Ares, J. A Central Regulatory System Largely Controls Transcriptional Activation and Repression Responses to Phosphate Starvation in Arabidopsis. PLOS Genetics 2010, 6, e1001102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sega, P.; Pacak, A. Plant PHR Transcription Factors: Put on A Map. Genes (Basel) 2019, 10, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sega, P.; Kruszka, K.; Bielewicz, D.; Karlowski, W.; Nuc, P.; Szweykowska-Kulinska, Z.; Pacak, A. Pi-Starvation Induced Transcriptional Changes in Barley Revealed by a Comprehensive RNA-Seq and Degradome Analyses. BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, K.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Du, L.; Guo, L.; Wu, Y.; Wu, P. OsPTF1, a Novel Transcription Factor Involved in Tolerance to Phosphate Starvation in Rice. Plant Physiology 2005, 138, 2087–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-F.; Li, L.-Q.; Xu, Q.; Kong, Y.-H.; Wang, H.; Wu, W.-H. The WRKY6 Transcription Factor Modulates PHOSPHATE1 Expression in Response to Low Pi Stress in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 2009, 21, 3554–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthikeyan, A.S.; Varadarajan, D.K.; Mukatira, U.T.; D’Urzo, M.P.; Damsz, B.; Raghothama, K.G. Regulated Expression of Arabidopsis Phosphate Transporters. Plant Physiology 2002, 130, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, D.; Chun, H.J.; Yun, D.-J.; Kim, M.C. Cross-Talk between Phosphate Starvation and Other Environmental Stress Signaling Pathways in Plants. Mol Cells 2017, 40, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong-Villalobos, L.; Cervantes-Pérez, S.A.; Gutiérrez-Alanis, D.; Gonzáles-Morales, S.; Martínez, O.; Herrera-Estrella, L. Phosphate Starvation Induces DNA Methylation in the Vicinity of Cis-Acting Elements Known to Regulate the Expression of Phosphate–Responsive Genes. Plant Signaling & Behavior 2016, 11, e1173300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Ye, X.; Shi, L.; Xu, F.; Ding, G. Molecular Identification of the Phosphate Transporter Family 1 (PHT1) Genes and Their Expression Profiles in Response to Phosphorus Deprivation and Other Abiotic Stresses in Brassica Napus. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0220374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desalegn, B.; Kebede, E.; Legesse, H.; Fite, T. Sugarcane Productivity and Sugar Yield Improvement: Selecting Variety, Nitrogen Fertilizer Rate, and Bioregulator as a First-Line Treatment. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G.C.; Rosa, P.A.L.; Jalal, A.; Oliveira, C.E. da S. ; Galindo, F.S.; Viana, R. da S.; De Carvalho, P.H.G.; Silva, E.C. da; Nogueira, T.A.R.; Al-Askar, A.A.; et al. Technological Quality of Sugarcane Inoculated with Plant-Growth-Promoting Bacteria and Residual Effect of Phosphorus Rates. Plants 2023, 12, 2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltangheisi, A.; Withers, P.J.A.; Pavinato, P.S.; Cherubin, M.R.; Rossetto, R.; Do Carmo, J.B.; da Rocha, G.C.; Martinelli, L.A. Improving Phosphorus Sustainability of Sugarcane Production in Brazil. GCB Bioenergy 2019, 11, 1444–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, N.; Palanisamy, V.; Channappa, M.; Ramanathan, V.; Ramaswamy, M.; Govindakurup, H.; Chinnaswamy, A. Genome-Wide In Silico Identification, Structural Analysis, Promoter Analysis, and Expression Profiling of PHT Gene Family in Sugarcane Root under Salinity Stress. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, N.; Kumar, R.; Pandey, S.K.; Dhansu, P.; Chennappa, M.; Nallusamy, S.; Govindakurup, H.; Chinnaswamy, A. In Silico Dissection of Regulatory Regions of PHT Genes from Saccharum Spp. Hybrid and Sorghum Bicolor and Expression Analysis of PHT Promoters under Osmotic Stress Conditions in Tobacco. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Zhao, C.-Z.; Liu, C.-S.; Huang, K.-L.; Guo, Q.-Q.; Chang, L.-L.; Xiong, H.; Li, X.-B. A Brassica Napus PHT1 Phosphate Transporter, BnPht1;4, Promotes Phosphate Uptake and Affects Roots Architecture of Transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol 2014, 86, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Li, G.; Sun, Z.; Chen, Y.; Guo, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, J.; Hou, H. Identification, Structure Analysis, and Transcript Profiling of Phosphate Transporters under Pi Deficiency in Duckweeds. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 188, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karandashov, V.; Bucher, M. Symbiotic Phosphate Transport in Arbuscular Mycorrhizas. Trends Plant Sci 2005, 10, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.; Hu, J.; Sun, S.; Xu, G. Conservation and Divergence of Both Phosphate- and Mycorrhiza-Regulated Physiological Responses and Expression Patterns of Phosphate Transporters in Solanaceous Species. New Phytologist 2007, 173, 817–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.-H.; Li, Z.-D.; Wang, X.-F.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, R.-H.; Gu, W.; Chen, D.; Yu, J.; He, S. Phosphate Transporters, PnPht1;1 and PnPht1;2 from Panax Notoginseng Enhance Phosphate and Arsenate Acquisition. BMC Plant Biology 2020, 20, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Gao, R.; Hu, G.; Gai, J.; Xu, G.; Xing, H. Molecular Cloning, Characterization and Expression Analysis of Two Members of the Pht1 Family of Phosphate Transporters in Glycine Max. PLoS One 2011, 6, e19752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Su, J.; Stephen, G.K.; Wang, H.; Song, A.; Chen, F.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, S.; Jiang, J. Overexpression of Phosphate Transporter Gene CmPht1;2 Facilitated Pi Uptake and Alternated the Metabolic Profiles of Chrysanthemum Under Phosphate Deficiency. Front Plant Sci 2018, 9, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, B.P.; Kumar, H.; Waight, A.B.; Risenmay, A.J.; Roe-Zurz, Z.; Chau, B.H.; Schlessinger, A.; Bonomi, M.; Harries, W.; Sali, A.; et al. Crystal Structure of a Eukaryotic Phosphate Transporter. Nature 2013, 496, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Pati, P.K.; Pati, A.M.; Nagpal, A.K. In-Silico Analysis of Cis-Acting Regulatory Elements of Pathogenesis-Related Proteins of Arabidopsis Thaliana and Oryza Sativa. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0184523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lata, C.; Prasad, M. Role of DREBs in Regulation of Abiotic Stress Responses in Plants. Journal of Experimental Botany 2011, 62, 4731–4748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tittarelli, A.; Milla, L.; Vargas, F.; Morales, A.; Neupert, C.; Meisel, L.A.; Salvo-G, H.; Peñaloza, E.; Muñoz, G.; Corcuera, L.J.; et al. Isolation and Comparative Analysis of the Wheat TaPT2 Promoter: Identification in Silico of New Putative Regulatory Motifs Conserved between Monocots and Dicots. Journal of Experimental Botany 2007, 58, 2573–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobkowiak, L.; Bielewicz, D.; Malecka, E.; Jakobsen, I.; Albrechtsen, M.; Pacak, A. The Role of the P1BS Element Containing Promoter-Driven Genes in Pi Transport and Homeostasis in Plants. Frontiers in plant science 2012, 3, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schünmann, P.H.D.; Richardson, A.E.; Smith, F.W.; Delhaize, E. Characterization of Promoter Expression Patterns Derived from the Pht1 Phosphate Transporter Genes of Barley (Hordeum Vulgare L. ). Journal of Experimental Botany 2004, 55, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, T.; Ono, T.; Shimizu, M.; Jinbo, T.; Mizuno, R.; Tomita, K.; Mitsukawa, N.; Kawazu, T.; Kimura, T.; Ohmiya, K.; et al. Promoter of Arabidopsis Thaliana Phosphate Transporter Gene Drives Root-Specific Expression of Transgene in Rice. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering 2005, 99, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Gu, M.; Sun, S.; Zhu, L.; Hong, S.; Xu, G. Identification of Two Conserved Cis-Acting Elements, MYCS and P1BS, Involved in the Regulation of Mycorrhiza-Activated Phosphate Transporters in Eudicot Species. New Phytologist 2011, 189, 1157–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.H.; Guo, N.; Wu, Z.Y.; Zhao, J.M.; Sun, J.T.; Wang, X.T.; Xing, H. P1BS, a Conserved Motif Involved in Tolerance to Phosphate Starvation in Soybean. Genet. Mol. Res. 2015, 14, 9384–9394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñaloza, E.; Santiago, M.; Cabrera, S.; Muñoz, G.; Corcuera, L.J.; Silva, H. Characterization of the High-Affinity Phosphate Transporter PHT1;4 Gene Promoter of Arabidopsis Thaliana in Transgenic Wheat. Biologia plant. 2017, 61, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Luo, Z.; Chen, J.; Jia, H.; Ai, P.; Chen, A.; Li, Y.; Xu, G. Characterization of Two Cis-Acting Elements, P1BS and W-Box, in the Regulation of OsPT6 Responsive to Phosphors Deficiency. Plant Growth Regul 2021, 93, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Sun, J.; Liu, D.; Li, B.; Zhang, A.; Li, Z.; Tong, Y. Characterization of the Promoter of Phosphate Transporter TaPHT1. 2 Differentially Expressed in Wheat Varieties. Journal of Genetics and Genomics 2009, 36, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudge, S.R.; Smith, F.W.; Richardson, A.E. Root-Specific and Phosphate-Regulated Expression of Phytase under the Control of a Phosphate Transporter Promoter Enables Arabidopsis to Grow on Phytate as a Sole P Source. Plant Science 2003, 165, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Jiang, P.; Qi, S.; Zhang, K.; He, Q.; Xu, C.; Ding, Z.; Zhang, K.; Li, K. Isolation and Functional Validation of Salinity and Osmotic Stress Inducible Promoter from the Maize Type-II H+-Pyrophosphatase Gene by Deletion Analysis in Transgenic Tobacco Plants. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0154041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Jing, R.; Mao, X. Functional Characterization of TaSnRK2. 8 Promoter in Response to Abiotic Stresses by Deletion Analysis in Transgenic Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci 2017, 8, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schünmann, P.H.D.; Richardson, A.E.; Vickers, C.E.; Delhaize, E. Promoter Analysis of the Barley Pht1;1 Phosphate Transporter Gene Identifies Regions Controlling Root Expression and Responsiveness to Phosphate Deprivation. Plant Physiol 2004, 136, 4205–4214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, B.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, K.; He, Q.; Zhao, X.; Cheng, W.; Ding, Z.; Zhang, K.; Li, K. Isolation and Characterization of a 295-Bp Strong Promoter of Maize High-Affinity Phosphate Transporter Gene ZmPht1; 5 in Transgenic Nicotiana Benthamiana and Zea Mays. Planta 2020, 251, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasirajan, L.; Valiyaparambth, R.; Kamaraj, K.; Sebastiar, S.; Hoang, N.V.; Athiappan, S.; Srinivasavedantham, V.; Subramanian, K. Deep Sequencing of Suppression Subtractive Library Identifies Differentially Expressed Transcripts of Saccharum Spontaneum Exposed to Salinity Stress. Physiologia Plantarum 2022, 174, e13645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsch, R.B.; Fry, J.E.; Hoffmann, N.L.; Wallroth, M.; Eichholtz, D.; Rogers, S.G.; Fraley, R.T. A Simple and General Method for Transferring Genes into Plants. Science 1985, 227, 1229–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J. DNA Protocols for Plants. In Molecular Techniques in Taxonomy; Hewitt, G.M., Johnston, A.W.B., Young, J.P.W., Eds.; NATO ASI Series; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1991; pp. 283–293 ISBN 978-3-642- 83962-7.

- Gasteiger, E.; Hoogland, C.; Gattiker, A.; Duvaud, S.; Wilkins, M.R.; Appel, R.D.; Bairoch, A. Protein Identification and Analysis Tools on the ExPASy Server. In The Proteomics Protocols Handbook; Walker, J.M., Ed.; Springer Protocols Handbooks; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2005; pp. 571–607 ISBN 978-1-59259- 890-8.

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J Mol Biol 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.D.; Higgins, D.G.; Gibson, T.J. CLUSTAL W: Improving the Sensitivity of Progressive Multiple Sequence Alignment through Sequence Weighting, Position-Specific Gap Penalties and Weight Matrix Choice. Nucleic Acids Research 1994, 22, 4673–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol Biol Evol 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Khedkar, S.; Bork, P. SMART: Recent Updates, New Developments and Status in 2020. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49, D458–D460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.D.; Bateman, A.; Clements, J.; Coggill, P.; Eberhardt, R.Y.; Eddy, S.R.; Heger, A.; Hetherington, K.; Holm, L.; Mistry, J.; et al. Pfam: The Protein Families Database. Nucleic Acids Research 2014, 42, D222–D230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paysan-Lafosse, T.; Blum, M.; Chuguransky, S.; Grego, T.; Pinto, B.L.; Salazar, G.A.; Bileschi, M.L.; Bork, P.; Bridge, A.; Colwell, L.; et al. InterPro in 2022. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 51, D418–D427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulo, N.; Bairoch, A.; Bulliard, V.; Cerutti, L.; De Castro, E.; Langendijk-Genevaux, P.S.; Pagni, M.; Sigrist, C.J.A. The PROSITE Database. Nucleic Acids Res 2006, 34, D227–D230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnhammer, E.L.; von Heijne, G.; Krogh, A. A Hidden Markov Model for Predicting Transmembrane Helices in Protein Sequences. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol 1998, 6, 175–182. [Google Scholar]

- Geourjon, C.; Deléage, G. SOPMA: Significant Improvements in Protein Secondary Structure Prediction by Consensus Prediction from Multiple Alignments. Bioinformatics 1995, 11, 681–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuffin, L.J.; Bryson, K.; Jones, D.T. The PSIPRED Protein Structure Prediction Server. Bioinformatics 2000, 16, 404–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, L.A.; Mezulis, S.; Yates, C.M.; Wass, M.N.; Sternberg, M.J.E. The Phyre2 Web Portal for Protein Modeling, Prediction and Analysis. Nat Protoc 2015, 10, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederstein, M.; Sippl, M.J. ProSA-Web: Interactive Web Service for the Recognition of Errors in Three-Dimensional Structures of Proteins. Nucleic Acids Research 2007, 35, W407–W410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, L.J.; Kuhn, M.; Stark, M.; Chaffron, S.; Creevey, C.; Muller, J.; Doerks, T.; Julien, P.; Roth, A.; Simonovic, M.; et al. STRING 8--a Global View on Proteins and Their Functional Interactions in 630 Organisms. Nucleic Acids Res 2009, 37, D412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almagro Armenteros, J.J.; Sønderby, C.K.; Sønderby, S.K.; Nielsen, H.; Winther, O. DeepLoc: Prediction of Protein Subcellular Localization Using Deep Learning. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 3387–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, T.N.; Brunak, S.; von Heijne, G.; Nielsen, H. SignalP 4. 0: Discriminating Signal Peptides from Transmembrane Regions. Nat Methods 2011, 8, 785–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, N.; Sicheritz-Pontén, T.; Gupta, R.; Gammeltoft, S.; Brunak, S. Prediction of Post-Translational Glycosylation and Phosphorylation of Proteins from the Amino Acid Sequence. PROTEOMICS 2004, 4, 1633–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Brunak, S. Prediction of Glycosylation across the Human Proteome and the Correlation to Protein Function. Pac Symp Biocomput 2002, 310–322. [Google Scholar]

- Potenza, C.; Aleman, L.; Sengupta-Gopalan, C. Targeting Transgene Expression in Research, Agricultural, and Environmental Applications: Promoters Used in Plant Transformation. In Vitro Cell.Dev.Biol.-Plant 2004, 40, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, F.; Akmar Abdullah, S.N.; Kadkhodaei, S.; Ijab, S.M.; Hamzah, L.; Aziz, M.A.; Rahman, Z.A.; Rabiah Syed Alwee, S.S. Functional Characterization of the Gene Promoter for an Elaeis Guineensis Phosphate Starvation-Inducible, High Affinity Phosphate Transporter in Both Homologous and Heterologous Model Systems. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2018, 127, 320–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, C. Isolation and Characterization of Constitutive and Wound Inducible Promoters and Validation of Designed Synthetic Stem/Root Specific Promoters for Sugarcane Transformation, 2015.

- Reese, M.G. Application of a Time-Delay Neural Network to Promoter Annotation in the Drosophila Melanogaster Genome. Computers & Chemistry 2001, 26, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahmuradov, I.A.; Umarov, R.K.; Solovyev, V.V. TSSPlant: A New Tool for Prediction of Plant Pol II Promoters. Nucleic Acids Research 2017, 45, e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, C.-N.; Lee, T.-Y.; Hung, Y.-C.; Li, G.-Z.; Tseng, K.-C.; Liu, Y.-H.; Kuo, P.-L.; Zheng, H.-Q.; Chang, W.-C. PlantPAN3. 0: A New and Updated Resource for Reconstructing Transcriptional Regulatory Networks from ChIP-Seq Experiments in Plants. Nucleic Acids Research 2019, 47, D1155–D1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Boden, M.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clementi, L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. MEME Suite: Tools for Motif Discovery and Searching. Nucleic Acids Research 2009, 37, W202–W208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higo, K.; Ugawa, Y.; Iwamoto, M.; Korenaga, T. Plant Cis-Acting Regulatory DNA Elements (PLACE) Database: 1999. Nucleic Acids Research 1999, 27, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a Database of Plant Cis-Acting Regulatory Elements and a Portal to Tools for in Silico Analysis of Promoter Sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aquino, S.; Carneiro, F.; Rêgo, E.; Alves, G.; Andrade, A.; Marraccini, P. Functional Analysis of Different Promoter Haplotypes of the Coffee (Coffea Canephora) CcDREB1D Gene through Genetic Transformation of Nicotiana Tabacum. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) 2018, 132, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remy, E.; Cabrito, T.R.; Batista, R.A.; Teixeira, M.C.; Sá-Correia, I.; Duque, P. The Pht1;9 and Pht1;8 Transporters Mediate Inorganic Phosphate Acquisition by the Arabidopsis Thaliana Root during Phosphorus Starvation. New Phytologist 2012, 195, 356–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jefferson, R.A.; Kavanagh, T.A.; Bevan, M.W. GUS Fusions: Beta-Glucuronidase as a Sensitive and Versatile Gene Fusion Marker in Higher Plants. EMBO J 1987, 6, 3901–3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Anal Biochem 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomczynski, P.; Sacchi, N. The Single-Step Method of RNA Isolation by Acid Guanidinium Thiocyanate–Phenol–Chloroform Extraction: Twenty-Something Years On. Nat Protoc 2006, 1, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvarajan, D.; Mohan, C.; Dhandapani, V.; Nerkar, G.; Jayanarayanan, A.N.; Vadakkancherry Mohanan, M.; Murugan, N.; Kaur, L.; Chennappa, M.; Kumar, R.; et al. Differential Gene Expression Profiling through Transcriptome Approach of Saccharum Spontaneum L. under Low Temperature Stress Reveals Genes Potentially Involved in Cold Acclimation. 3 Biotech 2018, 8, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoj, V.M.; Anunanthini, P.; Swathik, P.C.; Dharshini, S.; Ashwin Narayan, J.; Manickavasagam, M.; Sathishkumar, R.; Suresha, G.S.; Hemaprabha, G.; Ram, B.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Glyoxalase Pathway Genes in Erianthus Arundinaceus and Commercial Sugarcane Hybrid under Salinity and Drought Conditions. BMC Genomics 2019, 19, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharshini, S.; Manoj, V.M.; Suresha, G.S.; Narayan, J.A.; Padmanabhan, T.S.S.; Kumar, R.; Meena, M.R.; Manickavasagam, M.; Ram, B.; Appunu, C. Isolation and Characterization of Nuclear Localized Abiotic Stress Responsive Cold Regulated Gene 413 (SsCor413) from Saccharum Spontaneum. Plant Mol Biol Rep 2020, 38, 628–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, J.A.; Dharshini, S.; Manoj, V.M.; Padmanabhan, T.S.S.; Kadirvelu, K.; Suresha, G.S.; Subramonian, N.; Ram, B.; Premachandran, M.N.; Appunu, C. Isolation and Characterization of Water-Deficit Stress-Responsive α-Expansin 1 (EXPA1) Gene from Saccharum Complex. 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwin Narayan, J.; Chakravarthi, M.; Nerkar, G.; Manoj, V.M.; Dharshini, S.; Subramonian, N.; Premachandran, M.N.; Arun Kumar, R.; Krishna Surendar, K.; Hemaprabha, G.; et al. Overexpression of Expansin EaEXPA1, a Cell Wall Loosening Protein Enhances Drought Tolerance in Sugarcane. Industrial Crops and Products 2021, 159, 113035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, A.; V M, M.; Nerkar, G.; Mohan, C.; Dharshini, S.; Subramonian, N.; Premachandran, M.; Valarmathi, R.; Kumar, R.; Gomathi, R.; et al. Transgenic Sugarcane with Higher Levels of BRK1 Showed Improved Drought Tolerance. Plant Cell Reports 2023, 42, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).