Submitted:

02 October 2023

Posted:

09 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Design and Context

Procedure

Analysis

- Who is the audience?

- Why was the content included?

- When/where was the text produced?

- How does the document reflect the time that it was written?

- How would the intended audience be likely to interpret the content?

- How would a non-intended audience likely interpret the content?

- What does the text say and what is the context?

- What language does the text use?

- What is the tone of the text?

- Does the author(s) choice of words reveal covert assumptions along with an overt message?

Measures to Ensure Trustworthiness

Positionality Statement

Results

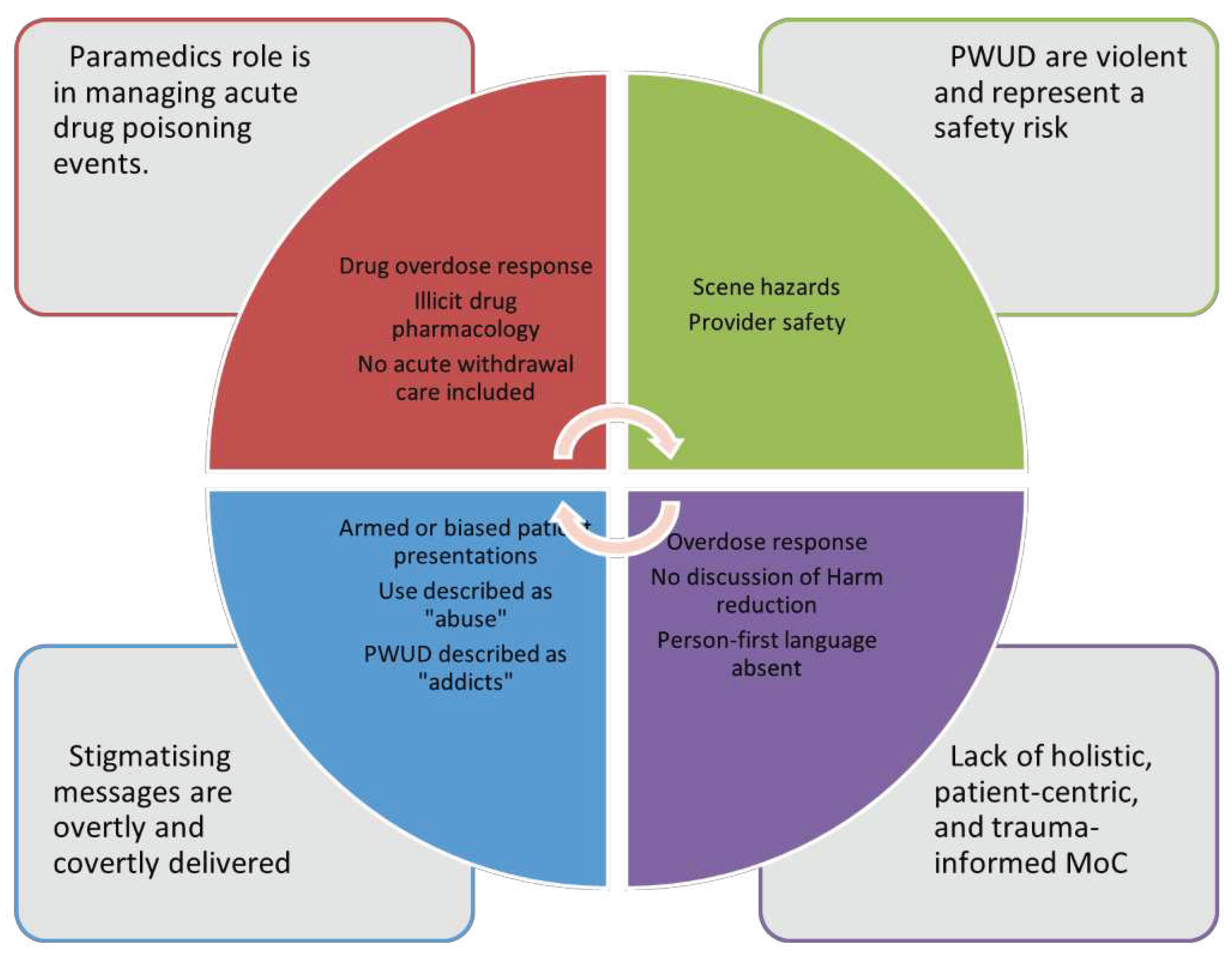

- The Paramedic Role: Acute drug poisoning events are the only time paramedics can intervene

- Patient Population: People who use drugs are often violent and represent a safety risk to paramedics

- Words Matter: Stigmatising messages are overtly and covertly delivered to paramedic students

- Models of Care: Lack of holistic, patient-centric, and trauma-informed practices.

The Paramedic Role: Acute Drug Poisoning Events Are the Only Time Paramedics Can Intervene

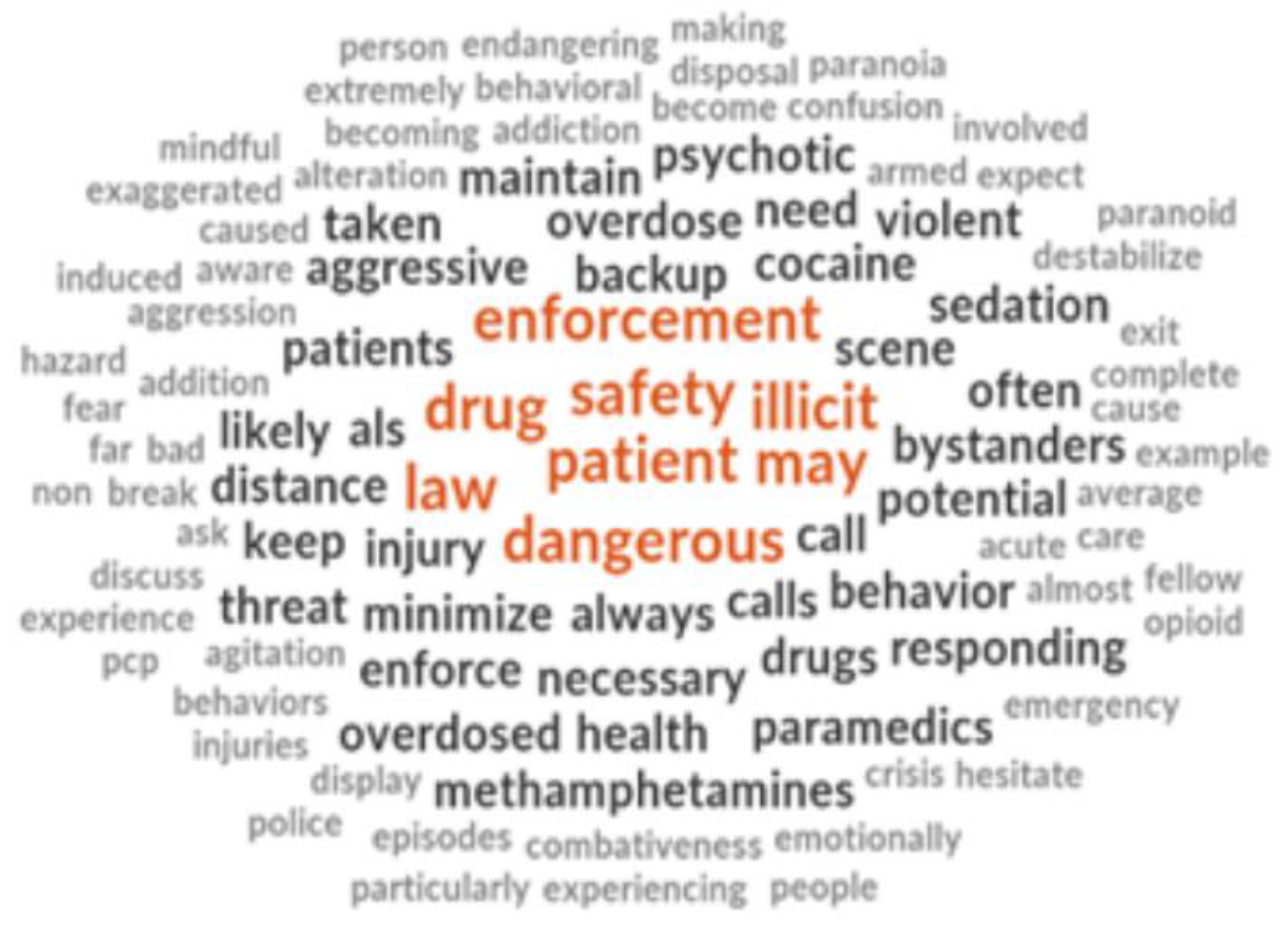

Patient Population: People Who Use Drugs Are Often Violent and Represent a Safety Risk to Paramedics

“Aggressive and dangerous behaviors are often caused by the use of illicit drugs” (5, p.1466)

“Be aware that patients who have taken an overdose may be extremely dangerous” (5, p.1406)

“Their behavior can quickly become violent, so always be mindful of your exit strategy when on scene. Do not hesitate to ask for law enforcement support if the scene seems likely to destabilize.” (5, p.1414)

“In addition to the threat from bystanders, the risk of a patient becoming aggressive is always present, particularly when cocaine or methamphetamines are involved.” (5, p.507)

“Such people are often paranoid, emotionally unstable, and almost always armed, making them a far more serious threat than an average patient with a non–drug-induced behavioral emergency.” (5, p.507)

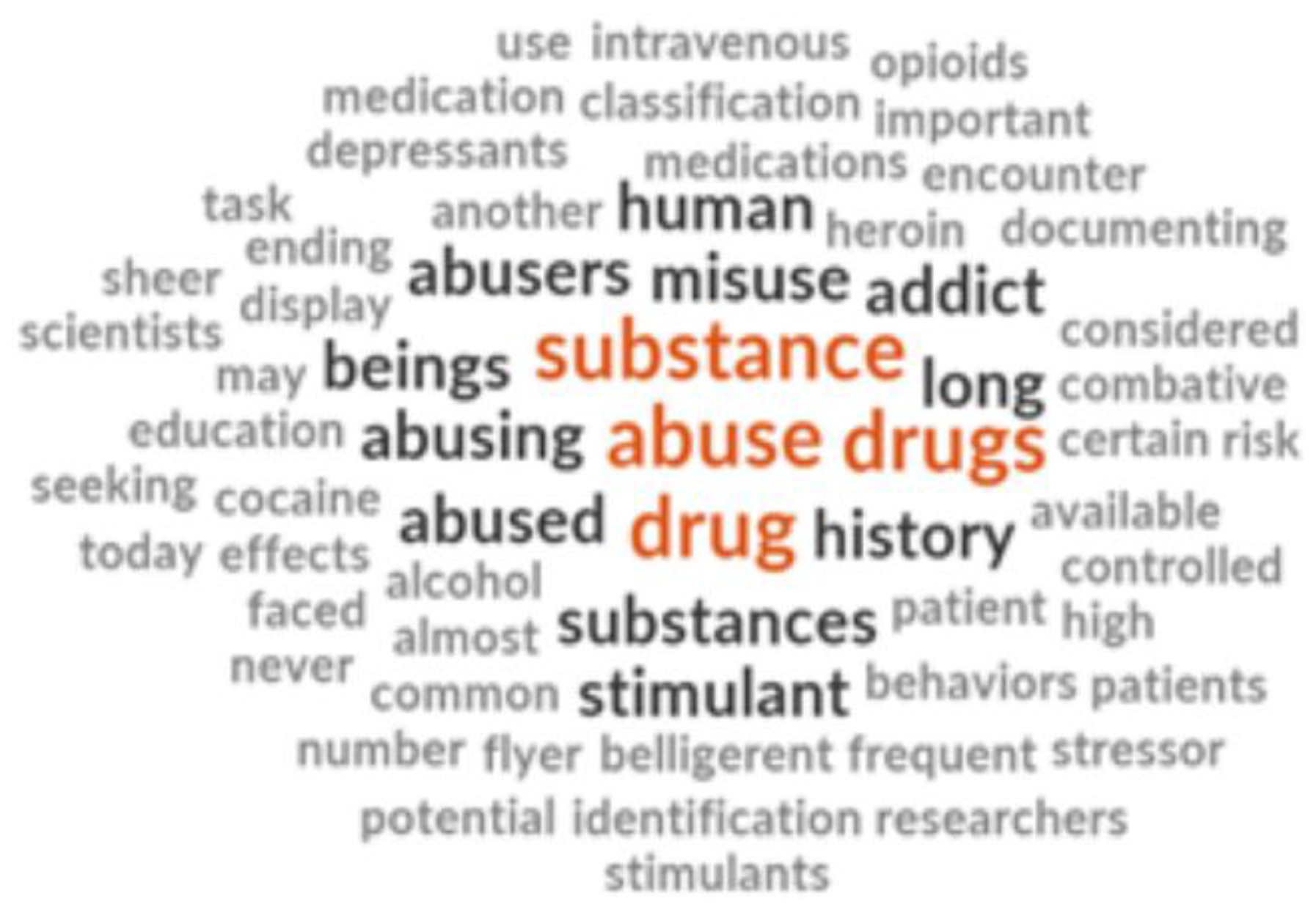

Words Matter: Stigmatising Messages are Overtly and Covertly Delivered to Paramedic Students

“Human beings have a long history of abusing drugs.”

“You are almost certain to encounter patients who abuse medications.” (5, p.639)

“Understanding the complex nature of substance-related disorders is your first step in providing professional, competent, and compassionate care to all affected people, from the homeless drug addict to the substance-dependent businessperson” (5, p.1476)

“Discuss stigma and mental health associated with addiction.”

“Watch Video: ‘Bringing Out the Dead’. Discussion: Professional or not?”

“A person with a drug addiction experiencing an acute psychotic break poses its own unique threats.” (5, p.1457)

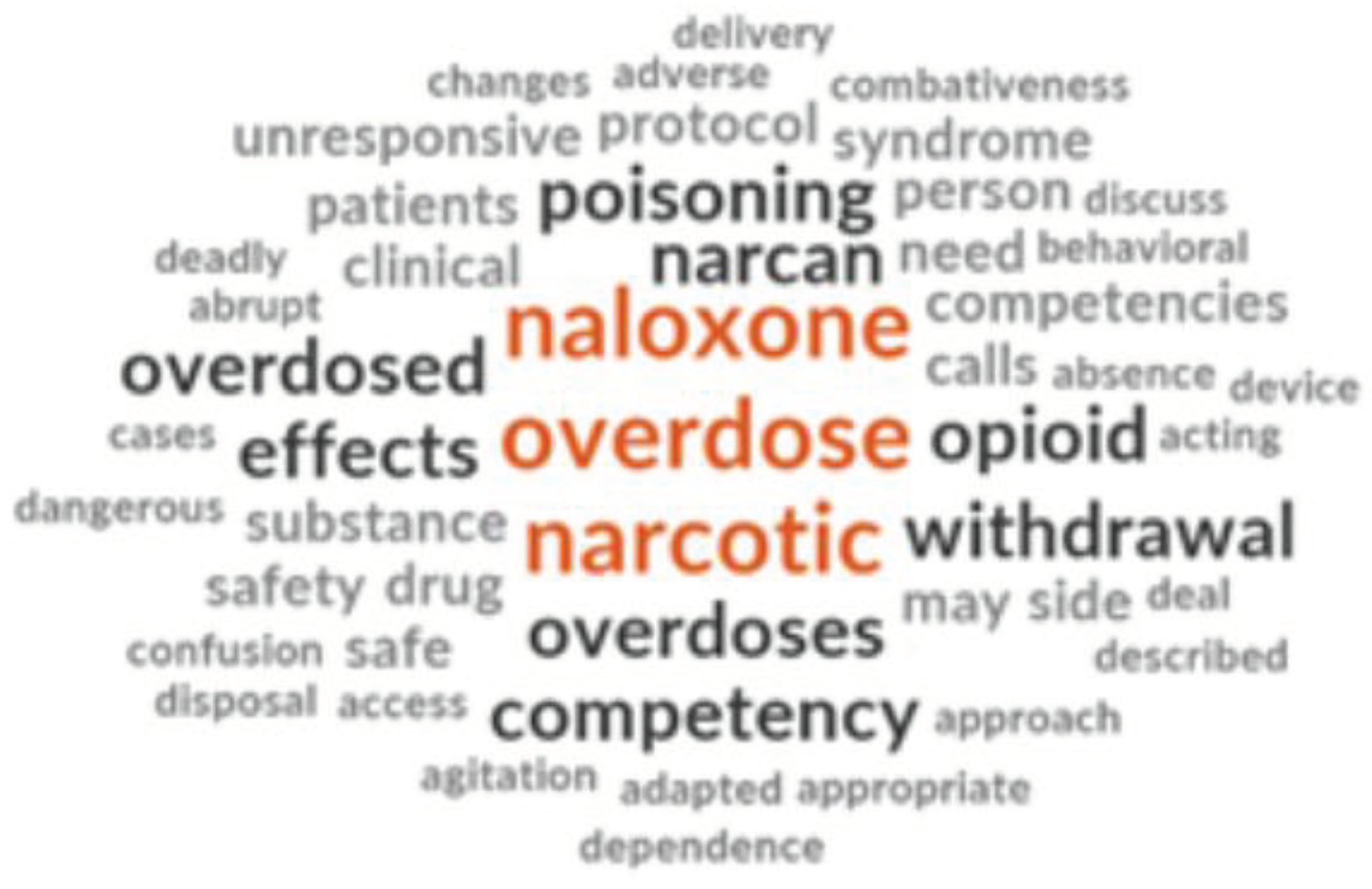

Models of Care: Lack of Holistic, Person-Centered, and Trauma-Informed Practices

“When it comes to drug use and overdoses, EMS has always been ’reactive.’ Someone overdoses, we give Narcan, transport.” (5, p.81).

“I decided that, as the organization that sees these situations firsthand, we should be part of the conversation, and hopefully, have a hand in developing a meaningful solution to the problem that is plaguing our county”. (5, p.81)

“Determining the most effective treatment for substance-related disorders requires an integrative approach of examining the social, biologic, cultural, cognitive, and psychological dimensions of the problem.” (5, p.1476)

“Discussion about Addiction vs. Dependence in context of opioids and alcohol”

“Apart from the physical effects of substance abuse, addiction carries a social stigma that can lead to feelings of isolation, paranoia, and depression” (5, p.1403)

“As a paramedic, you may be unable to explore all these areas during a short transport to the medical facility, particularly because much of your time will be devoted to ensuring the safety of your crew and managing the patient’s ABCs.” (5, p.1476)

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Belzak, L.; Halverson, J. The opioid crisis in Canada: A national perspective. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2018, 38, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BCEHS. 2021 Overdose Numbers [Internet]. Available online: http://www.bcehs.ca/about site/Documents/Overdose%20Information%202021.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- British Columbia Coroner Service. BC Coroners Service Review Panel: A Review of Illicit Drug Toxicity Deaths [Internet]. Vancouver. 2022. Available online: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/birth-adoption-death-marriage-and-divorce/deaths/coroners-service/death-review-panel/review_of_illicit_drug_toxicity_deaths_2022.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Bolster, J.; Armour, R.; O’Toole, M.; Lysko, M.; Batt, A. The Paramedic Role in Caring for People Who Use Illicit and Controlled Drugs. Paramedicine 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoove, M.A.; Dietz, P.M.; Jolley, D. Overdose deaths following previous non-fatal heroin overdose: Record linkage of ambulance attendance and death registry data. Drug Alcohol. Rev. 2009, 28, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburn, N.P.; Ryder, C.W.; Angi, R.M.; Snavely, A.C.; Nelson, R.D.; Bozeman, W.P.; McGinnis, H.D.; Winslow, J.T.; Stopyra, J.P. One-Year Mortality and Associated Factors in Patients Receiving Out-of-Hospital Naloxone for Presumed Opioid Overdose. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2020, 75, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, S.G.; Baker, O.; Bernson, D.; Schuur, J.D. One-Year Mortality of Patients After Emergency Department Treatment for Nonfatal Opioid Overdose. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2020, 75, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moe, J.; A Puzzling Trend: Denying Ambulance Transport Post-Overdose [Internet]. Vancouver: Jessica Moe. 2020. Available online: https://www.bcemergencynetwork.ca/lounge/denying-ambulance-transport-post-overdose/?unapproved=201109&moderation-hash=343f8c52b7dfb466c666d0e233a8ed43#comment-201109 (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Martin, R.A.; Duk, D.; Holcombe, J.; Buccheit, R.; Mendiratta, A.; Whittle, J.S. Exploring Barriers to Implementing an Emergency Medical Services Naloxone Leave Behind Program. J. Emerg. Med. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, B.L.; Earl, B.M. Measurement of Empathy Levels in Undergraduate Paramedic Students. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2013, 28, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kus, G.; Wilson, B. Exploring empathy levels among Canadian paramedic students. Faculty Staff. Publications - Public. Safety. 2018, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegano, R.; Ricketts, J.B. Empathy levels in Canadian paramedic students: A longitudinal study. Fac. Staff. Publ. Public Saf. 2018, 11, 1492–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kus, L. Exploring empathy levels among Canadian paramedic students. Int. J. Paramed. Pract. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batt, A. Do we preach what we practice? The development of competency frameworks in healthcare professions. Thesis. 2017.

- Batt, A.M.; Williams, B.; Brydges, M.; Leyenaar, M.; Tavares, W. New ways of seeing: Supplementing existing competency framework development guidelines with systems thinking. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 2021, 26, 1355–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batt, A.; Poirier, P.; Bank, J.; Bolster, J.; Bowles, R.; Donelon, B.; Dunn, N.; Essington, T.; Johnston, W. Developing the National Occupational Standard for Paramedics in Canada - Update 1. 2022, 45, 6–8.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); Office of the Surgeon General (US). Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General's Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health [Internet]. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services. 2016 Nov. CHAPTER 7, VISION FOR THE FUTURE: A PUBLIC HEALTH APPROACH. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424861/ (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- McNaughton, C. Transitions through homelessness, substance use, and the effect of material marginalization and psychological trauma. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2009, 15, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; Pollak, A. N.; Elling, B.; Aehlert, B. Nancy Caroline's emergency care in the streets, 8th ed.; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Paramedic Association of Canada. National Occupational Competency Profile for Paramedics [Internet]. 2011. Available online: https://paramedic.ca/documents/2011-10-31-Approved-NOCP-English-Master.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Bessen S, Metcalf SA, Saunders EC; et al. Barriers to naloxone use and acceptance among opioid users, first responders, and emergency department providers in New Hampshire, USA. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2019, 74, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruis, N.E.; McLean, K.; Perry, P. Exploring first responders’ perceptions of medication for addiction treatment: Does stigma influence attitudes? J Subst Abuse Treatment. 2021, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, G.A. Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Leary. The Essential Guide to Doing Your Research Project. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. 2014.

- Cleland, J.; MacLeod, A.; Ellaway, R.H. CARDA: Guiding document analyses in health professions education research. Med. Educ. 2023, 57, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis, Qualitative Research in Sport. Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, S.; Boyd, J.; Collins, A.; Kennedy, M.C.; Fairbairn, N.; McNeil, R. Characterizing fentanyl-related overdoses and implications for overdose response: Findings from a rapid ethnographic study in Vancouver, Canada. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 2018, 1, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccarone, D. Fentanyl in the US heroin supply: A rapidly changing risk environment. Int. J. Drug Policy 2017, 46, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbairn, N.; Coffin, P.O.; Walley, A.Y. Naloxone for heroin, prescription opioid, and illicitly made fentanyl overdoses: Challenges and innovations responding to a dynamic epidemic. Int. J. Drug Policy 2017, 46, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCann, T.V.; Savic, M.; Ferguson, N.; Bosley, E.; Smith, K.; Roberts, L.; Emond, K.; Lubman, D.I. Paramedics' perceptions of their scope of practice in caring for patients with non-medical emergency-related mental health and/or alcohol and other drug problems: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams-Yuen, J.; Minaker, G.; Buxton, J.; et al. ‘You’re not just a medical professional’: Exploring paramedic experiences of overdose response within Vancouver’s downtown eastside. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamouzian, M.; Kuo, M.; Crabtree, A.; Buxton, J.A. Correlates of seeking emergency medical help in the event of an overdose in British Columbia, Canada: Findings from the Take Home Naloxone program. Int. J. Drug Policy 2019, 71, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire BJ, O'Neill BJ. Emergency Medical Service Personnel's Risk From Violence While Serving the Community. Am. J. Public. Health 2017, 107, 1770–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hokee, M.Y.; Makkink, A.W.; Vincent-Lambert, C. Workplace violence against paramedic personnel: A protocol for a scoping review. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e067246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spelten, E.; van Vuuren, J.; O’Meara, P. Workplace violence against emergency health care workers: What Strategies do Workers use? BMC Emerg. Med. 2022, 22, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.M.; Davis, A.L.; Shepler, L.J. A Systematic Review of Workplace Violence Against Emergency Medical Services Responders. NEW SOLUTIONS A J. Environ. Occup. Health Policy 2020, 29, 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada. Stigma: Why Words Matter [Internet]. 2022. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/publications/healthy-living/stigma-why-words-matter.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. Available online: https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-09/CCSA-Language-and-Stigma-in-Substance-Use-Addiction-Guide-2019-en.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Ellis, K.; Walters, S.; Friedman, S.R.; Ouellet, L.J.; Ezell, J.; Rosentel, K.; Pho, M.T. Breaching Trust: A Qualitative Study of Healthcare Experiences of People Who Use Drugs in a Rural Setting. Front. Sociol. 2020, 10, 593925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MedPro. Nonverbal Communication as an Essential Element of Patient-Centred Care. Available online: https://www.medpro.com/nonverbal-communication-patient-centered-care (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Partnership to End Addiction. Words Matter: The Language of Addiction. Available online: https://drugfree.org/article/shouldnt-use-word-addict/ (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Canadian Public Health Association. Language Matters [Internet]. 2019. Available online: https://www.cpha.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/resources/stbbi/language-tool-e.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Lavalley, J.; Kastor, S.; Tourangeau, M. Western Aboriginal Harm Reduction Society; Goodman A, Kerr T. You just have to have other models, our DNA is different: The experiences of indigenous people who use illicit drugs and/or alcohol accessing substance use treatment. Harm Reduct. J. 2020, 24, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agata MP Atayde Sacha, C. Hauc, Lily G. Bessette, Heidi Danckers & Richard Saitz (2021) Changing the narrative: A call to end stigmatizing terminology related to substance use disorders. Addict. Res. Theory 2021, 29, 359–362. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.; Crawford, S.; Perry, G.E. Achieving meaningful participation of people who use drugs and their peer organizations in a strategic research partnership. Harm Reduct. J. 2019, 16, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claborn, K.R.; Creech, S.; Whittfield, Q.; Parra-Cardona, R.; Daugherty, A.; Benzer, J. Ethical by Design: Engaging the Community to Co-design a Digital Health Ecosystem to Improve Overdose Prevention Efforts Among Highly Vulnerable People Who Use Drugs. Front. Digit. Health 2022, 26, 880849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ti, L.; Tzemis, D.; Buxton, J. Engaging people who use drugs in policy and program development: A review of the literature. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy. 2012, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowland, P.; Kumagai, A.K. MD. K. MD. Dilemmas of Representation: Patient Engagement in Health Professions Education. Acad. Med. 2018, 93, 869–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souleymanov, R.; Kuzmanović, D.; Marshall, Z.; et al. Ethics Community-Based Res. People Who Use Drugs: Results A Scoping. Rev. BMC Med. Ethics. 2016, 17, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Clemmons. Using the Intended–Enacted–Experienced Curriculum Model to Map the Vision and Change Core Competencies in Undergraduate Biology Programs and Courses. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2022, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).