Submitted:

06 October 2023

Posted:

09 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Fly strains

Immunocytochemistry and Imaging

Quantification of fluorescence intensity

Results

Integrin knockdown enhances RasV12 hyperplastic phenotype

Integrin knockdown enhances RasV12-associated cell shape changes and growth

Integrins restrict the ability of RasV12 tumour cells to stimulate apoptosis in neighbouring wild type cells

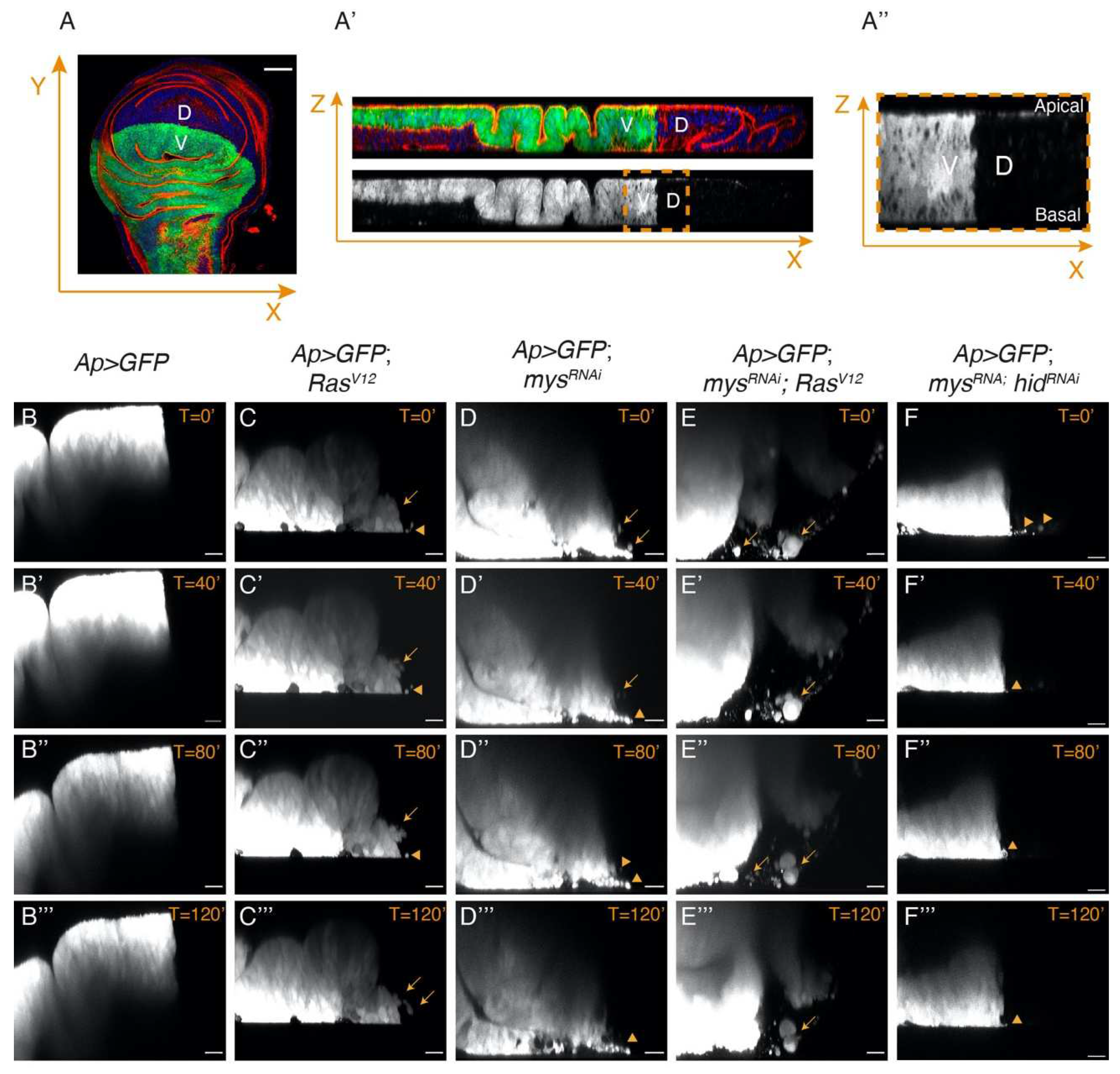

Integrins limit the ability of epithelial RasV12 tumour cells to leave the epithelium and move

Discussion

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Parkin, D.M.; Pineros, M.; Znaor, A.; Bray, F. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: An overview. Int J Cancer 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, H.; Ivaska, J. Every step of the way: integrins in cancer progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer 2018, 18, 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, J.D.; Byron, A.; Humphries, M.J. Integrin ligands at a glance. J Cell Sci 2006, 119, 3901–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagnet, S.; Faraldo, M.M.; Kreft, M.; Sonnenberg, A.; Raymond, K.; Glukhova, M.A. Signaling events mediated by a3b1 integrin are essential for mammary tumorigenesis. Oncogene 2014, 33, 4286–4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, D.E.; Kurpios, N.A.; Zuo, D.; Hassell, J.A.; Blaess, S.; Mueller, U.; Muller, W.J. Targeted disruption of beta1-integrin in a transgenic mouse model of human breast cancer reveals an essential role in mammary tumor induction. Cancer Cell 2004, 6, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, N.E.; Zhang, Z.; Madamanchi, A.; Boyd, K.L.; O'Rear, L.D.; Nashabi, A.; Li, Z.; Dupont, W.D.; Zijlstra, A.; Zutter, M.M. The alpha(2)beta(1) integrin is a metastasis suppressor in mouse models and human cancer. J Clin Invest 2011, 121, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, H.H.; Xiong, J.; Ghotra, V.P.; Nirmala, E.; Haazen, L.; Le Devedec, S.E.; Balcioglu, H.E.; He, S.; Snaar-Jagalska, B.E.; Vreugdenhil, E.; et al. beta1 integrin inhibition elicits a prometastatic switch through the TGFbeta-miR-200-ZEB network in E-cadherin-positive triple-negative breast cancer. Sci Signal 2014, 7, ra15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.; Gregory, S.L.; Martin-Bermudo, M.D. Integrins as mediators of morphogenesis in Drosophila. Developmental Biology 2000, 223, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brower, D.L. Platelets with wings:the maturation of Drosophila integrin biology. Current Opinion in Cell Biol. 2003, 15, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokel, C.; Brown, N.H. Integrins in Development: moving on, respoding to, and sticking to the extracellular matrix. Developmental Cell 2002, 3, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Miñán, A.; Martín-Bermudo, M.D.; Gonzéalez-reyes, A. Integrin signaling regulates spindle orientation in Drosophila to preserve the follicular-epithelium monolayer. Current Biology 2007, 17, 683–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovegrove, H.E.; Bergstralh, D.T.; St Johnston, D. The role of integrins in Drosophila egg chamber morphogenesis. Development 2019, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa-Cruz Mateos, C.; Valencia-Exposito, A.; Palacios, I.M.; Martin-Bermudo, M.D. Integrins regulate epithelial cell shape by controlling the architecture and mechanical properties of basal actomyosin networks. PLoS Genet 2020, 16, e1008717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Exposito, A.; Gomez-Lamarca, M.J.; Widmann, T.J.; Martin-Bermudo, M.D. Integrins Cooperate With the EGFR/Ras Pathway to Preserve Epithelia Survival and Architecture in Development and Oncogenesis. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 892691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, B.K.; Irvine, K.D. The wing imaginal disc. Genetics 2022, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brower, D.L.; Jaffe, S.M. Requirements for integrins during Drosophila wing development. Nature 1989, 342, 285–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, M.; DiAntonio, A.; Leptin, M. The function of PS integrins in Drosophila wing morphogenesis. Development 1989, 107, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Gimenez, P.; Brown, N.H.; Martin-Bermudo, M.D. Integrin-ECM interactions regulate the changes in cell shape driving the morphogenesis of the Drosophila wing epithelium. J Cell Sci 2007, 120, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, C. Drosophila melanogaster: a model and a tool to investigate malignancy and identify new therapeutics. Nat Rev Cancer 2013, 13, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzoyan, Z.; Sollazzo, M.; Allocca, M.; Valenza, A.M.; Grifoni, D.; Bellosta, P. Drosophila melanogaster: A Model Organism to Study Cancer. Front Genet 2019, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, S.A.; Beare, D.; Gunasekaran, P.; Leung, K.; Bindal, N.; Boutselakis, H.; Ding, M.; Bamford, S.; Cole, C.; Ward, S.; et al. COSMIC: exploring the world's knowledge of somatic mutations in human cancer. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, D805–D811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Feig, L.; Montell, D.J. Two distinct roles for Ras in a developmentally regulated cell migration. Development 1996, 122, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa-Fombuena, G.; Lobo-Pecellin, M.; Marin-Menguiano, M.; Rojas-Rios, P.; Gonzalez-Reyes, A. Live imaging of the Drosophila ovarian niche shows spectrosome and centrosome dynamics during asymmetric germline stem cell division. Development 2021, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prober, D.A.; Edgar, B.A. Ras1 promotes cellular growth in the Drosophila wing. Cell 2000, 100, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler Beatty, J.; Molnar, C.; Luque, C.M.; de Celis, J.F.; Martin-Bermudo, M.D. EGFRAP encodes a new negative regulator of the EGFR acting in both normal and oncogenic EGFR/Ras-driven tissue morphogenesis. PLoS Genet 2021, 17, e1009738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genevet, A.; Polesello, C.; Blight, K.; Robertson, F.; Collinson, L.M.; Pichaud, F.; Tapon, N. The Hippo pathway regulates apical-domain size independently of its growth-control function. J Cell Sci 2009, 122, 2360–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumby, A.M.; Richardson, H.E. scribble mutants cooperate with oncogenic Ras or Notch to cause neoplastic overgrowth in Drosophila. EMBO J 2003, 22, 5769–5779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.L.; Streuli, C.H. Integrins and epithelial cell polarity. J Cell Sci 2014, 127, 3217–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulas, S.; Conder, R.; Knoblich, J.A. The Par complex and integrins direct asymmetric cell division in adult intestinal stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 11, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, C.; Reis, J.G.T.; Rusten, T.E. Ras(V12); scrib(-/-) Tumors: A Cooperative Oncogenesis Model Fueled by Tumor/Host Interactions. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, J.; Abisoye-Ogunniyan, A.; Metcalf, K.J.; Werb, Z. Concepts of extracellular matrix remodelling in tumour progression and metastasis. Nature communications 2020, 11, 5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, F.D.; Rubin, G.M. Ectopic expression of activated Ras1 induces hyperplastic growth and increased cell death in Drosophila imaginal tissues. Development 1998, 125, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murcia, L.; Clemente-Ruiz, M.; Pierre-Elies, P.; Royou, A.; Milan, M. Selective Killing of RAS-Malignant Tissues by Exploiting Oncogene-Induced DNA Damage. Cell Rep 2019, 28, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Ohsawa, S.; Igaki, T. Mitochondrial defects trigger proliferation of neighbouring cells via a senescence-associated secretory phenotype in Drosophila. Nature communications 2014, 5, 5264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabu, C.; Xu, T. Oncogenic Ras stimulates Eiger/TNF exocytosis to promote growth. Development 2014, 141, 4729–4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Garijo, A.; Fuchs, Y.; Steller, H. Apoptotic cells can induce non-autonomous apoptosis through the TNF pathway. Elife 2013, 2, e01004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, E.; Valon, L.; Levillayer, F.; Levayer, R. Competition for Space Induces Cell Elimination through Compaction-Driven ERK Downregulation. Curr Biol 2019, 29, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramovs, V.; Te Molder, L.; Sonnenberg, A. The opposing roles of laminin-binding integrins in cancer. Matrix Biol 2017, 57-58, 213–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.Y.; Li, J.Q.; Zhang, L.L.; Wang, H.; Wang, F.H.; Tao, Y.W.; Wang, Y.Q.; Guo, Q.R.; Li, J.J.; Liu, Y.; et al. The Biological Functions and Clinical Applications of Integrins in Cancers. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 579068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zheng, W.; Wang, H.; Cheng, Y.; Fang, Y.; Wu, F.; Sun, G.; Sun, G.; Lv, C.; Hui, B. Application of Animal Models in Cancer Research: Recent Progress and Future Prospects. Cancer Manag Res 2021, 13, 2455–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huck, L.; Pontier, S.M.; Zuo, D.M.; Muller, W.J. beta1-integrin is dispensable for the induction of ErbB2 mammary tumors but plays a critical role in the metastatic phase of tumor progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 15559–15564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.; Barlow, B.; O'Rear, L.; Jarvis, B.; Li, Z.; Dickeson, K.; Dupont, W.; Zutter, M. Loss of the alpha2beta1 integrin alters human papilloma virus-induced squamous carcinoma progression in vivo and in vitro. PLoS One 2011, 6, e26858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kren, A.; Baeriswyl, V.; Lehembre, F.; Wunderlin, C.; Strittmatter, K.; Antoniadis, H.; Fassler, R.; Cavallaro, U.; Christofori, G. Increased tumor cell dissemination and cellular senescence in the absence of beta1-integrin function. EMBO J 2007, 26, 2832–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran-Jones, K.; Ledger, A.; Naylor, M.J. beta1 integrin deletion enhances progression of prostate cancer in the TRAMP mouse model. Sci Rep 2012, 2, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Wang, W.; Liu, T.; Shang, C.; Huang, J.; Liao, Y.; Qin, S.; Chen, Y.; Liu, P.; Liu, J.; et al. High Expression of Integrin alpha3 Predicts Poor Prognosis and Promotes Tumor Metastasis and Angiogenesis by Activating the c-Src/Extracellular Signal-Regulated Protein Kinase/Focal Adhesion Kinase Signaling Pathway in Cervical Cancer. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoletov, K.; Kato, H.; Zardouzian, E.; Kelber, J.; Yang, J.; Shattil, S.; Klemke, R. Visualizing extravasation dynamics of metastatic tumor cells. J Cell Sci 2010, 123, 2332–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Senda, N.; Iida, A.; Sehara-Fujisawa, A.; Ishii, T.; Sato, F.; Toi, M.; Itou, J. In silico analysis-based identification of the target residue of integrin alpha6 for metastasis inhibition of basal-like breast cancer. Genes Cells 2019, 24, 596–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Zhang, X.; Ren, J.; Pang, Z.; Wang, C.; Xu, N.; Xi, R. Integrin signaling is required for maintenance and proliferation of intestinal stem cells in Drosophila. Dev Biol 2013, 377, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, A.; Quazi, T.A.; Tang, H.W.; Manzar, N.; Singh, V.; Thakur, A.; Ateeq, B.; Perrimon, N.; Sinha, P. A Drosophila model of oral peptide therapeutics for adult intestinal stem cell tumors. Dis Model Mech 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Denholm, B.; Bunt, S.; Bischoff, M.; VijayRaghavan, K.; Skaer, H. Epidermal growth factor signalling controls myosin II planar polarity to orchestrate convergent extension movements during Drosophila tubulogenesis. PLoS Biol 2014, 12, e1002013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamada, M.; Zallen, J.A. Square Cell Packing in the Drosophila Embryo through Spatiotemporally Regulated EGF Receptor Signaling. Dev Cell 2015, 35, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desgrosellier, J.S.; Cheresh, D.A. Integrins in cancer: biological implications and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer 2010, 10, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianconi, D.; Unseld, M.; Prager, G.W. Integrins in the Spotlight of Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enomoto, M.; Vaughen, J.; Igaki, T. Non-autonomous overgrowth by oncogenic niche cells: Cellular cooperation and competition in tumorigenesis. Cancer Sci 2015, 106, 1651–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraamides, C.J.; Garmy-Susini, B.; Varner, J.A. Integrins in angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer 2008, 8, 604–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zutter, M.M.; Santoro, S.A.; Staatz, W.D.; Tsung, Y.L. Re-expression of the alpha 2 beta 1 integrin abrogates the malignant phenotype of breast carcinoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995, 92, 7411–7415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varzavand, A.; Hacker, W.; Ma, D.; Gibson-Corley, K.; Hawayek, M.; Tayh, O.J.; Brown, J.A.; Henry, M.D.; Stipp, C.S. alpha3beta1 Integrin Suppresses Prostate Cancer Metastasis via Regulation of the Hippo Pathway. Cancer Res 2016, 76, 6577–6587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Lewis, W.; Page-McCaw, A. Basement membrane mechanics shape development: Lessons from the fly. Matrix Biol 2019, 75-76, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Lin, H.P.; Yang, P.; Humphries, B.; Gao, T.; Yang, C. Integrin alpha9 depletion promotes beta-catenin degradation to suppress triple-negative breast cancer tumor growth and metastasis. Int J Cancer 2019, 145, 2767–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Xing, X.; Cai, L.B.; Zhu, L.; Yang, X.M.; Wang, Y.H.; Yang, Q.; Nie, H.Z.; Zhang, Z.G.; Li, J.; et al. Integrin alpha9 Suppresses Hepatocellular Carcinoma Metastasis by Rho GTPase Signaling. J Immunol Res 2018, 2018, 4602570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegerfeldt, Y.; Tusch, M.; Brocker, E.B.; Friedl, P. Collective cell movement in primary melanoma explants: plasticity of cell-cell interaction, beta1-integrin function, and migration strategies. Cancer Res 2002, 62, 2125–2130. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).