1. Introduction

In the field of medicine, self-medication (SM) stands as a multifaceted concept shaped by numerous defining parameters. Authors have frequently constructed their interpretations of SM, taking into account the manner of medication acquisition, the absence of professional healthcare guidance, the source of medication, and the motivations behind SM [

1] The World Health Organization (WHO) characterizes self-medication as the utilization of medicinal products by individuals to address self-identified health issues or symptoms, including the intermittent or ongoing use of a prescribed medication for chronic or recurring conditions [

2]. Notably, the World Medical Association advocates for responsible self-medication, denoting the legitimate use of non-prescription medicines, either autonomously or following healthcare professional advice [

3]

There is focus on the prevalent phenomenon of parental self-medication—a practice witnessed worldwide, where parents tend to address their children’s common maladies without consulting a medical practitioner. Studies have reported varying prevalence rates, spanning from 25.2% to 96% in different countries [

4]. The COVID-19 pandemic has further accentuated self-medication tendencies, given the challenges associated with accessing healthcare services [

5,

6]. The SM extended even in cases involving children with chronic gastrointestinal ailments such as IBD, celiac disease, or chronic hepatitis, where parents have resorted to self-medication despite associated risks [

6]. Adverse responses, frequently of a severe nature, were notably observed in pediatric individuals exhibiting suboptimal nutritional status. This phenomenon was predominantly attributed to the failure to tailor the administered medication dosage to the patient’s body mass, adhering closely to the guidance provided in the drug’s accompanying documentation. The profound influence of an ideal protein-to-calorie ratio on early-life weight gain and the equilibrium of the gut microbiota is a widely recognized fact within the scientific community, particularly during the initial year of an individual’s life [

7,

8].

Across both developed and developing nations, a significant proportion of parents opt to manage their children’s commonplace symptoms and ilnesses like fever, cough, cold, or diarrhea without prior consultation with a healthcare professional [

4]. The utilization of analgesics, antipyretics, anti-inflammatory agents, and cough or cold remedies emerges as a recurring pattern in pediatric self-medication, with paracetamol (acetaminophen) being one of the most frequently employed non-prescription analgesics and antipyretics [

9,

10].

It is noteworthy that SM in children differs substantially from its practice in adults. In pediatric cases, it is not a self-initiated, voluntary decision driven by the patient’s knowledge and perceived symptoms but rather hinges on the subjective assessment of a child’s condition by a parent or caregiver [

11].

While the usage of over-the-counter (OTC) medications for children raises concerns about their potential risks and unproven efficacy, studies have identified factors motivating parents to opt for such treatments, including accessibility, convenience, and time-saving benefits [

12]. In certain qualitative inquiries, parents have cited the use of OTC medicines as a means of gaining control over their children’s behavior, alleviating discomfort associated with a sick child, and calming or sedating them—a phenomenon termed "social medication" [

13]. Surprisingly, research indicates that self-medication behaviors are strongly influenced by non-cognitive factors, such as habits and symptom affinity, while cognitive factors like knowledge and risk comprehension exhibit limited association [

14].

In light of these findings, it becomes apparent that parents and caregivers are prone to errors due to their limited understanding of medication, encompassing aspects like dosage, timing, preparation, and potential drug interactions, as well as inadequate knowledge regarding the selection, acquisition, storage, and disposal of medicines [15-17]. Parents often resort to self-medication for their children’s fever without a precise understanding of the underlying cause or appropriate treatment [

18,

19]. Additionally, parental knowledge regarding the toxicity of medications appears deficient, with a considerable percentage underestimating the risks, such as the belief that paracetamol overdose is non-fatal [

20].

To gain deeper insights into the factors driving self-medication behaviors and to develop effective prevention strategies, various models have been employed. The Health Belief Model emerges as a valuable tool for examining the relationship between health beliefs and self-medication behaviors [

21,

22]. According to this model, individuals are more inclined to engage in health-promoting practices when they perceive a health risk, believe they can mitigate it, and are motivated to do so.

Several studies have employed the Health Belief Model to investigate self-medication among parents. Findings suggest that educational interventions based on this model can enhance parents’ perceived self-efficacy, reduce barriers to timely addressing their child’s health issues, and improve medication adherence [

23].

Our research predominantly employs the Health Belief Model as a framework, with the aim of understanding how patients’ attitudes towards self-medication for children are influenced by exposure to information that emphasizes the risks associated with treating them without a medical prescription.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methods, sample, research instruments and data analysis

To fulfill the objectives of this research, a survey based on questionnaire was developed by a panel of specialists in medicine, psichology and communication sciences. A total of 250 adult participants, each with at least one child, were invited to partake in this study. These individuals were selected randomly from the patient databases of two general practitioners situated in Bucharest, Romania. Among these invitees, 210 willingly consented to engage in the study, yielding a commendable response rate of 80%. Subsequently, these 210 participants were subject to random allocation into two distinct groups: one designated as Group 1 (G1=108), which received exposure to medical information concerning the perils of self-medication. This information was conveyed through the Romanian translation of educational materials akin to those disseminated by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) addressing the use of over-the-counter (OTC) medications for children [

24]. In contrast, the other group, denoted as Group 2 (G2=102), did not receive such medical information.

The distribution of the questionnaire, accompanied by data protection documentation and informed consent, was carried out via email. It was explicitly communicated to respondents that no personally identifiable information, including names, addresses, email addresses, or health statuses, would be collected as part of this research endeavor. Participation in the study was entirely voluntary, and respondents were afforded the choice to abstain from questionnaire completion if they wished not to participate or to proceed with survey submission.

The questionnaire itself comprised a total of 20 inquiries. To gauge the influence of exposure to medical information on self-medication practices, two distinct versions of the questionnaire were crafted. One version was intended for parents who had received pertinent medical information concerning the hazards associated with self-administering medication to their children. In this scenario, the medical information closely mirrored the FDA’s messages pertaining to the risks of parents medicating their children without prior medical consultation. The second version, devoid of any medical educational content, was designated for the remaining participants. Both versions, despite this difference, incorporated identical questions designed to evaluate the following aspects:

1. Attitude of parents towards self-medication of their children. To avoid latent respondents’ biases, we addressed an indirect question where the participants assessed (on a 5-point Likert scale, where 5 means – strongly agree and 1– strongly disagree) the case of a target-mother who self-treated the fever of her two years child without medical advice.

2. Perceived severity of self-medication, in this case, the severity of side-effects of self-medication. The second variable measured in the questionnaire was the perceived severity of self-medication, specifically the severity of side effects resulting from self-medication. Respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement or disagreement (on a 5-point Likert scale) with the statement "If I give medicine to my child without medical advice, there may be other side consequences/complications for their health."

3. Perceived susceptibility of self-medication, which refers to the extent to which respondents perceive the risks of self-medicating their children with a specific medication, such as acetaminophen. To measure this variable, we included a statement (e.g. "Administering acetaminophen to my child without medical advice could be harmful") to which respondents indicated their level of agreement or disagreement on a 5-point Likert scale.

4. Perceived barriers to adopting appropriate health behavior. Perceived barriers to seeking medical advice refer to the obstacles or challenges that might prevent parents from adopting appropriate health behavior. In this study, we assessed the perceived quality of the relationship between respondents and their family doctor (GP), using a 5-point Likert scale.

5. Perceived self-efficacy. Perceived self-efficacy refers to the extent to which respondents believed they could follow the advice of medical professionals and avoid self-medicating their children. This construct was measured through a statement (I am able to avoid treating my child’s illness without medical advice), to which participants expressed their level of agreement or disagreement using a 5-point Likert scale.

6. The beliefs regarding the use of over-the counter-medicine from the pharmacy. The questionnaire included a statement to measure the beliefs of respondents regarding the use of over-the-counter medicine from the pharmacy. The statement read, "If purchasing over-the-counter medication is legal, then a doctor’s advice is not necessary." Respondents were asked to express their agreement or disagreement on a 5-point Likert scale.

7. Socio-demographics. Information about the respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, education, and number of children) was also collected during the study.

The data was collected between October and November 2022.

2.2. Statistical analysis

To analyse the collected data, statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 27 software. We used descriptive statistics (counts, percentages) to present the results or mean and standard deviation (SD). To investigate associations within the data, the Chi-square test was employed, while for comparing results, the t-test was applied, with effect sizes reported using Cohen’s d. Specifically, t-tests were conducted to assess disparities in parental tendencies toward self-medicating their children between two distinct groups: those exposed to medical information and those not exposed. The choice of the t-test was informed by the substantial sample sizes in each group, exceeding 100 participants, and was consistent with previous research findings that indicated negligible differences between parametric and nonparametric tests when dealing with Likert scales [

25,

26].

Each response on the 5-point Likert scale was assigned a numerical value, ranging from 1 for complete disagreement to a maximum of 5 for total agreement. Consequently, in the ensuing analysis, higher mean values reflected stronger agreement, while lower mean values indicated heightened disagreement with the statements under evaluation.

To ascertain the independent influence of various socio-demographic factors on respondents’ agreement with the survey statements, ordinal regression analyses were conducted. These analyses were executed in situations where statistically significant differences were discerned between the exposed and unexposed groups. In all such scenarios, none of the socio-demographic variables emerged as statistically significant contributors in modeling the responses..

3. Results

Table 1 presents the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample. We identified that participants within the exposed group were younger when compared to the unexposed group. Another significant difference between the two groups was related to the percentage of participants within the rural areas, where a significantly higher percentage had residence in such environments. For all other characteristics, differences were not statistically significant.

Another aspect that we investigated was the assessment of the GP’s activity and the assessment of the Health System. These aspects might play an important role in the parents’ decision to self-treat their children. After being exposed to the medical information, we observed that there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups of parents. We can observe a very high level of trust in their personal GP for all participants, with an average, overall score of 4.23 and a SD of 1.12 (maximum score is 5). At the same time, we observed a significantly lower score for trust in the health system, with an overall average of 2.56 and a SD of 1.03.

Table 2.

Assessment of the medical system.

Table 2.

Assessment of the medical system.

| |

Category |

Mean ± SD |

p-value |

| Assessment of the GP’s activity |

Unexposed |

4.28 ± 1.07 |

0.48 |

| Exposed |

4.18 ± 1.16 |

| Assessment of the Health System |

Unexposed |

2.69 ± 1.08 |

0.89 |

| Exposed |

2.44 ± 0.97 |

The way parents answered the questions evaluating their attitudes toward self-medication is depicted in detail in Supplementary material no. 2.

To assess the effects of exposure to the medical information on beliefs and behaviors regarding self-medication, we used a t-test to determine the differences between the mean scores obtained by each group of participants in the study (unexposed vs exposed).

The data highlights that one significant variable could explain the different effects of medical information on self-medication, namely the beliefs of parents on the use of over-the-counter medicine – the beliefs toward the administration of acetaminophen when the child is ill.

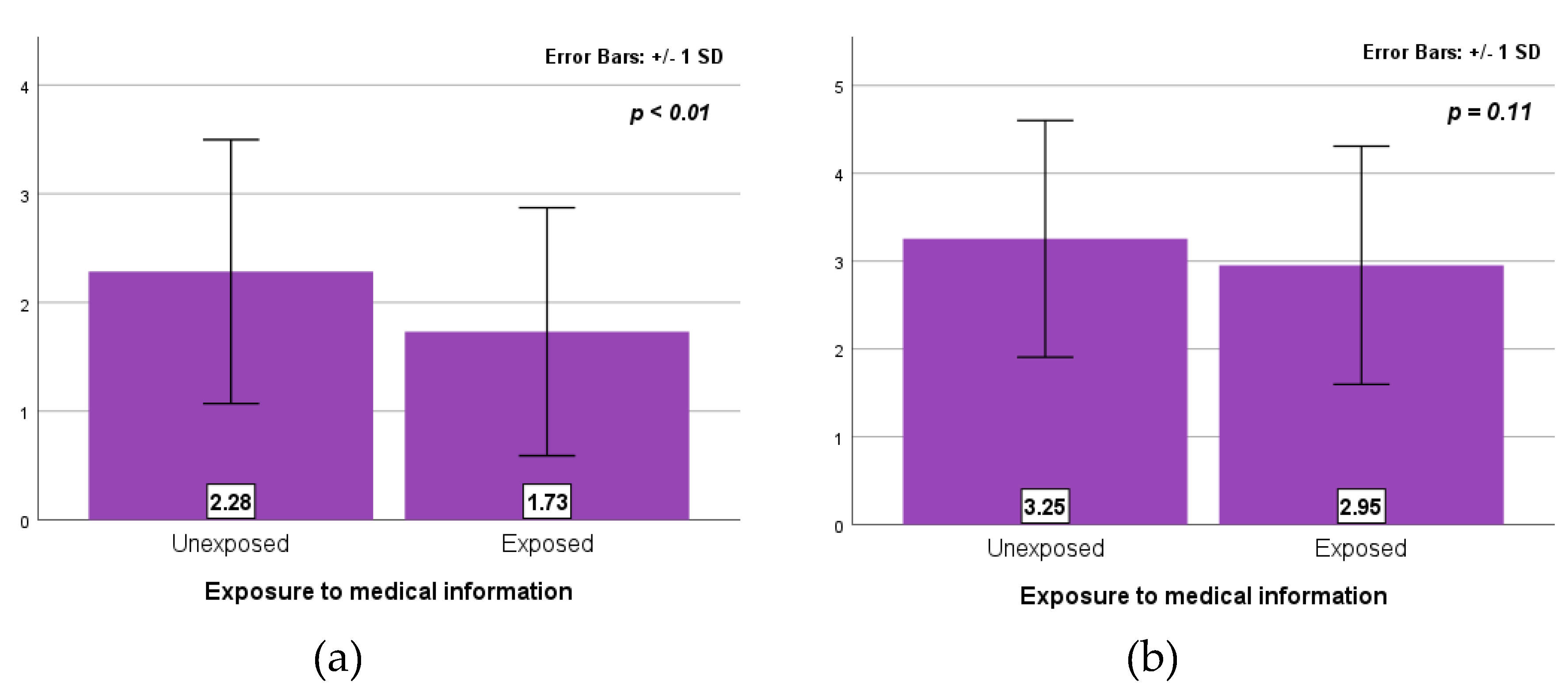

On average, respondents not exposed to medical information had an average score of 2.28, with a standard deviation (SD) of 1.21. Almost one-quarter of the unexposed participants in the study declared to be neutral (23.5%). For the exposed group, the average score was 1.73, with an SD of 1.14, and 13% neutral (

Figure 1a). The result of the t-test is statistically significant (t=3.4, df=208, p<0.001), with a mean difference of 0.55 (95% CI 0.16-0.23). The effect size, calculated using Cohen’s D was medium, with a value of 0.47 (95% CI 0.19 -0.74). Thus, participants unexposed to educational material tended to believe that medications obtained from a pharmacy without a medical prescription can be administered without medical advice, while participants within the exposed group tended not to embrace this idea. Therefore, a significant difference between the two groups was obtained showing that our H6 hypothesis was sustained.

Furthermore, respondents not exposed to medical information tended to agree that medications for children obtained from a pharmacy, without a medical prescription (i.e. acetaminophen) can be administered to children without the advice of a doctor, the average score is 3.25, with an SD of 1.35. On the other hand, respondents warned of the risks of self-medication tended not to embrace this idea, having a lower average score, of 2.95, with an SD of 1.36. No statistical difference between the two groups (t=1.61, df=208, p=0.11) was obtained (

Figure 1b).

Regarding the other variables measured according to the HBM model – perceived severity, perceived self-efficacy, and perceived barriers – all these have not been statistically significant to self-medication cognitions. For example, both those exposed to the warning information and those who were not exposed have agreed that they are unable to avoid treatment of their ill child without medical advice. Although, they disagreed with all self-medication practices (

Table 3).

A statistically significant, positive, weak correlation (r=0.258, p<0.01) was obtained when we tested the relation between the level of satisfaction with the GP’s advice and the level of the perceived threat of self-medication (Table 5). This holds the second hypothesis (H2) of our study, which suggests that when the family doctor is highly regarded, the perception of the risk of self-treating the child is also high, and vice-versa.

Table 4.

Person correlation of perceived severity of self-medication and level of satisfaction with the GP.

Table 4.

Person correlation of perceived severity of self-medication and level of satisfaction with the GP.

| |

Perceived severity of self-medication |

Assessment of the GP |

| Perceived severity of self-medication |

Correlation |

1 |

.258**

|

| Sig. (2-tailed) |

|

p < 0.01 |

| N |

210 |

210 |

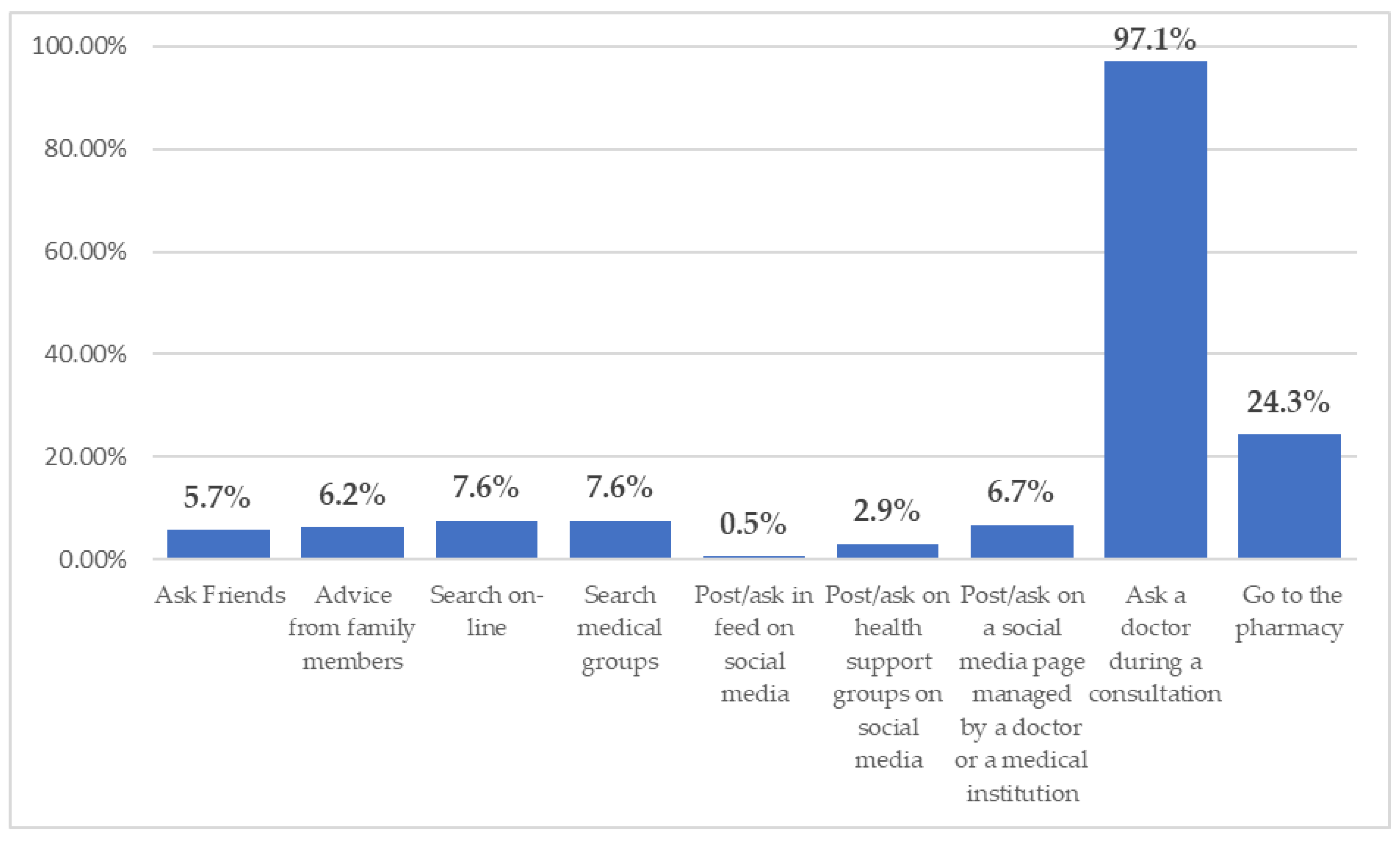

Another evaluated aspect was related to the methods used by the parents to seek advice related to the child’s current episode of disease. The responses favor the idea of being consulted by a medical doctor, with almost all of the parents choosing this option. Another method of getting help was to consult directly with a pharmacist, which was a usual attitude for approximately one-quarter of the parents (24.3%). This indicates a high degree of trust in direct contact with health personnel, being a doctor or a pharmacist. On the other hand, methods that mainly rely on getting advice from friends or familiar, each one is usually used by approximately 5% of the parents. Even though internet resources and social media seems to play a very important role in adult’s life, different methods of communicating with specialists in the field, or getting help from peers from social media groups were generally low in our sample, with percentages ranging from 0.5% to 7.6% (

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

Our findings have highlighted three important pieces of data. Firstly, parents’ beliefs about the use of over-the-counter medicines, specifically their beliefs about the purchase and use of OTCs when their child is sick, have been identified as a significant variable in explaining the different effects of exposure to medical warning communication on self-medication risks. Secondly, there is a relationship between the level of satisfaction with the family doctor and the perceived threat of self-medication. This suggests that when a patient is satisfied with the general advice provided by their GP, he/she will be more aware of the risks of self-medicating without medical advice. Thirdly, both parents who were exposed to medical information and those who were not warned about the risks of self-medication reported feeling "helpless" to avoid self-medication when their child is sick, which in terms of the HBM model means a low level of perceived self-efficacy, or those beliefs that avoiding self-medication is risky. Even if they have overall negative attitudes about self-medication and know that it should generally be avoided, they respond that they cannot avoid it in a specific context. Fourthly, the variables measured according to the HBM model – perceived severity, perceived self-efficacy, and perceived barriers – were not found to be statistically significant in relation to self-medication cognitions.

Research suggests that perceived susceptibility to illness is an important predictor of preventive health behaviors [

27]. This study reports a statistically significant difference in perceived susceptibility after the educational intervention between the intervention and control group which could be a meaningful indication of the effect of the educational intervention (information warnings in these cases) on improving the perceived susceptibility of individuals in the intervention group. In many other studies, it has been shown that if the intervention based on HBM affected and raised the susceptibility, then the probability of risky behaviors was decreased [22,28-30]. Contrary to our results, the study conducted by Jaberee SR et al, showed that perceived susceptibility was not a predictor of self-medication preventive behaviors [

31].

Another study points out that the largest change was in perceived susceptibility, whereas the smallest changes were in perceived severity and perceived benefit [

32]. The results are contradictory to those of other studies in which researchers used this model for education. The studies realized by Muwfaq Younis N, et al, and Fathi M, et al., showed that all HBM constructs play an important role in adopting preventive behaviors [

33,

34]. Regarding the mean level of perceived self-efficacy in another study, the main reason for using OTC medications, described by almost two-thirds of mothers, was to preserve their children’s lives in emergencies. The most commonly used medications were antipyretics, for reducing the child’s fever (91,9%) [

35]. It was noted that caregivers with more children tend to self-medicate their children if compared to caregivers with their first child [

36]. Another study reported that most of the caregivers agreed that it was important to give medicine to a child at home when he/she feels sick and medication given can prevent worsening of the disease [

37].

Our study highlights the relationship between the level of satisfaction with the family doctor and the perceived threat of self-medication. In addition to primary care practices being the first line of support, information, and support from professionals are highly valued [

38]. Most people trust their family physician’s perspectives [

39]. Another study showed that participants who were involved in decisions on how to manage their children’s illness by their GPs facilitated responsible use of antibiotics [

40]. In studies conducted by Fathi et al. and Mohsen et al., it was found that physicians and health staff were effective in promoting preventive behaviors [

34,

41]. Physicians were also identified as the most important source of information, and educational programs had an important influence on the behaviour of the parents, concerning treating or preventing children’s diseases [42-44]. The study conducted by Biezen et al. shows that communication between GPs and parents is therefore a vital component in reducing antibiotic prescribing in general practice [

45]. Low confidence in medical care systems increased the risk of antibiotic self-medication and knowing prescription-only regulation for sales of antibiotics by community pharmacies was a protective factor against antibiotic self-medication in children [

46]. The primary healthcare system, through family doctors, can effectively improve the continuity of care for patients with chronic diseases, studies on diabetes reaching to this conclusion [

47]. Other studies show that compliance with recommendations from health workers may also be correlated with confidence in vaccine efficacy because they can share personal knowledge about being immunized and motivate vaccine uptake efficacy [

48]. HBM is proven as an acceptable, reliable method of identifying factors correlated with self-medication behavior [

49].

Both traditional and recent health promotion interventions [

50,

51] have demonstrated that both public health campaigns and medical education provided in contexts such as doctor-patient interpersonal communication can have an impact on health-related behaviors. Regarding self-medication and parental education about preventing self-treating of their children, interventions targeting specific groups with personalized messages are sporadic. In this regard, our research has been able to show that providing a self-medication prevention message can bring about at least a change in the attitudes and opinions of a target group.

It is becoming increasingly evident that, in the future, healthcare institutions should start and engage in audience education activities [

52] in order to tailor communication policies and healthcare delivery. Patients should be trained to acquire the skills to evaluate the structure of accurate and credible information to prevent the spread of contradictory medical information that could lead to disastrous consequences for the scientific authority of doctors and, consequently, public health. Providing medical education in doctor-patient encounters remains one of the most efficent and handy way of delivering proper health related behaviors.

Educating patients about responsible self-medication can bring several benefits. It helps avoid unnecessary visits to medical facilities for minor, seasonal, or repeated ailments in patients who have responded well to initial supervised therapy and do not have concurrent chronic conditions. It also enables early identification of non-responsive cases, leading to timely referral to emergency medical services in collaboration with the parent/patient. Moreover, it relieves doctors from evaluating ongoing conditions that can be effectively managed with repeatedly indicated therapies [

2,

3].

Based on both previous research and our findings, we can conclude that the Health Belief Model (HBM) is an effective theoretical and methodological tool for assessing self-medication practices more accurately.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

As far as we know, there is no other study conducted in Romania on the cognitive factors of parental self-medication using the Health Belief Model. Our current and previous studies raised awareness of the personal factors that lead to a higher prevalence of parental self-medication in Romania. Furthermore, our findings could contribute to better regulation of the practice of self-medication through public policies. Still, our research data remains limited and must be replicated on different sociodemographic groups and areas for a better understanding of the factors that might affect the use of self-medication in children among Romanian parents.

5. Conclusions

In general, our respondents evaluate negatively the practices of self-medication, especially the treatment of their children without medical advice. However, their attitudes towards self-medication vary depending on their beliefs about administering certain medications, such as acetaminophen, which is frequently used when children have a fever.

As our data showed, a perceived level of satisfaction in relation to family physicians could be a significant way of controlling and avoiding the treatment of children without medical advice.

Furthermore, our findings suggest that the high level of awareness among respondents about the risks of self-medication can be attributed to the medical information campaigns conducted by various healthcare professionals. Therefore, future health education campaigns need to be targeted specifically, with messages that guide how to act in particular cases depending on the medication used and the child’s condition. In Romania, messages on self-medication from health professionals have generally been too general, thus, when combined with pharmacy medication procurement practices, can lead to a misunderstanding of how medications should be used.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials No.1. Responses to the main topics of the questionnaire (N=210).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.T. and A.D.; methodology, P.T and A.D.; software, O.R. and A.V.; validation, I.I., S.I.C. and S.D..; formal analysis, I.I. and O.R.; investigation, P.T. and V.H.; resources, V.H. and P.T.; data curation, S.I.C. and A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, P.T, A.D. and S.I.C.; writing—review and editing, P.T, A.D. and S.I.C.; visualization, O.R., I.I and A.V.; supervision, S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Romanian Academy of Medical Sciences (no. 2 SNI/27.02.2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. The study did not involve human or biological sampling.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable here.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baracaldo-Santamaria, D.; Trujillo-Moreno, M.J.; Perez-Acosta, A.M.; Feliciano-Alfonso, J.E.; Calderon-Ospina, C.A.; Soler, F. Definition of self-medication: a scoping review. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2022, 13, 20420986221127501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Guidelines for the regulatory assessment of medicinal products for use in self-medication. 2000.

- World Medical Association. WMA Statement on Self-Medication. Available online: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-statement-on-self-medication/ (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Mathias, E.G.; D’Souza, A.; Prabhu, S. Self-Medication Practices among the Adolescent Population of South Karnataka, India. J Environ Public Health 2020, 2020, 9021819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayosanmi, O.S.; Alli, B.Y.; Akingbule, O.A.; Alaga, A.H.; Perepelkin, J.; Marjorie, D.; Sansgiry, S.S.; Taylor, J. Prevalence and Correlates of Self-Medication Practices for Prevention and Treatment of COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazemioula, G.; Golestani, S.; Alavi, S.M.A.; Taheri, F.; Gheshlagh, R.G.; Lotfalizadeh, M.H. Prevalence of self-medication during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health 2022, 10, 1041695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantazi, A.C.; Balasa, A.L.; Mihai, C.M.; Chisnoiu, T.; Lupu, V.V.; Kassim, M.A.K.; Mihai, L.; Frecus, C.E.; Chirila, S.I.; Lupu, A.; et al. Development of Gut Microbiota in the First 1000 Days after Birth and Potential Interventions. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tincu, I.F.; Pacurar, D.; Tincu, R.C.; Becheanu, C. Influence of Protein Intake during Complementary Feeding on Body Size and IGF-I Levels in Twelve-month-old Infants. Balkan Med J 2019, 37, 54–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-Castro, A.J.; Ruiz-Noa, Y.; Martínez-de la Cruz, G.C.; Ramírez-Morales, M.A.; Deveze-Álvarez, M.A.; Escutia-Gutiérrez, R.; Carranza-Álvarez, C.; Domínguez, F.; Maldonado-Miranda, J.J.; Ruiz-Padilla, A.J. Factors and Practices Associated with Self-Medicating Children among Mexican Parents. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jozwiak-Bebenista, M.; Nowak, J.Z. Paracetamol: mechanism of action, applications and safety concern. Acta Pol Pharm 2014, 71, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela Ortiz, M.; Sánchez Ruiz-Cabello, F.J.; Uberos, J.; Checa Ros, A.F.; Valenzuela Ortiz, C.; Augustín Morales, M.C.; Muñoz Hoyos, A. Self-medication, self-prescription and medicating “by proxy” in paediatrics. Anales de Pediatría (English Edition) 2017, 86, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, A.Y.; Durham, C.O.; Sterrett, J.J.; Wallace, J.B. Safety of Over-the-Counter Medications in Pregnancy. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 2019, 44, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benotsch, E.G.; Koester, S.; Martin, A.M.; Cejka, A.; Luckman, D.; Jeffers, A.J. Intentional misuse of over-the-counter medications, mental health, and polysubstance use in young adults. J Community Health 2014, 39, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Druică, E.; Băicuș, C.; Ianole-Călin, R.; Fischer, R. Information or Habit: What Health Policy Makers Should Know about the Drivers of Self-Medication among Romanians. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sil, A.; Sengupta, C.; Das, A.K.; Sil, P.D.; Datta, S.; Hazra, A. A study of knowledge, attitude and practice regarding administration of pediatric dosage forms and allied health literacy of caregivers for children. J Family Med Prim Care 2017, 6, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, E.M. Risks of Self-Medication Practices. Current Drug Safety 2010, 5, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauf, Z.; Putra, D.P.; Masrul, M.; Semiarty, R. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Families Practices in Selecting, Obtaining, Using, Storing, and Disposing of Medicines on Self-Medication Behavior in Indonesia. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences 2021, 9, 1570–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daifallah, A.; Jabr, R.; Al-Tawil, F.; Elkourdi, M.; Salman, Z.; Koni, A.; Samara, A.; Al-Jabi, S.W.; Zyoud, S.e.H. An assessment of parents’ knowledge and awareness regarding paracetamol use in children: a cross-sectional study from Palestine. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzouk, A.; Lajili, M.; Ben Yahya, I.; Bouaziz, A. Self-Medication of Children by Parents during a Febrile Episode. Indian Journal of Pediatrics 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zyoud, S.H.; Al-Jabi, S.W.; Sweileh, W.M.; Nabulsi, M.M.; Tubaila, M.F.; Awang, R.; Sawalha, A.F. Beliefs and practices regarding childhood fever among parents: a cross-sectional study from Palestine. BMC Pediatr 2013, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khani Jeihooni, A.; Mohammadkhah, F.; Razmjouie, F.; Harsini, P.A.; Sedghi Jahromi, F. Effect of educational intervention based on health belief model on mothers monitoring growth of 6-12 months child with growth disorders. BMC Pediatr 2022, 22, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeihooni, A.K.; Hidarnia, A.; Kaveh, M.H.; Hajizadeh, E.; Askari, A. The Effect of an Educational Program Based on Health Belief Model on Preventing Osteoporosis in Women. Int J Prev Med 2015, 6, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaman, C.R.; Ibrahim, N.; Shaker, V.; Cham, C.Q.; Ho, M.C.; Visvalingam, U.; Shahabuddin, F.A.; Abd Rahman, F.N.; MRT, A.H.; Kaur, M.; et al. Parental Factors Associated with Child or Adolescent Medication Adherence: A Systematic Review. Healthcare (Basel) 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spring, S. Got a Sick Kid? Don’t Guess. Read the Label. Make sure you’re giving your children the right medicine and the right amount. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-drugs/got-sick-kid-dont-guess-read-label-make-sure-youre-giving-your-children-right-medicine-and-right (accessed on 2 July 2023).

- Mircioiu, C.; Atkinson, J. A Comparison of Parametric and Non-Parametric Methods Applied to a Likert Scale. Pharmacy (Basel) 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, G. Likert scales, levels of measurement and the "laws" of statistics. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2010, 15, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.L.; Jensen, J.D.; Scherr, C.L.; Brown, N.R.; Christy, K.; Weaver, J. The Health Belief Model as an explanatory framework in communication research: exploring parallel, serial, and moderated mediation. Health Commun 2015, 30, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydartabar, R.; Hatefnia, E.; Kazemnejad, A.; Ayubi, E.; Mansori, K. The Effects of Model-Based Educational Intervention on Self-medication Behavior in Mothers with Children less than 2- year. International Journal of Pediatrics 2016, 4, 3229–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movahed, E.; Shojaei zadeh, D.; Zarei pour, M.a.; Arefi, Z.; Sha ahmadi, F.; Ameri, M. The Effect of Health Belief Model- Based Training (HBM) on Self- Medication among the Male High School Students. Iranian Journal of Health Education and Health Promotion 2014, 2, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Moridi, E.; Fazelniya, Z.; Yari, A.; Gholami, T.; Hasirini, P.A.; Khani Jeihooni, A. Effect of educational intervention based on health belief model on accident prevention behaviours in mothers of children under 5-years. BMC Womens Health 2021, 21, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei Jaberee, S.; Aghamolaei, T.; Mohseni, S.; Eslami, H.; Hassani, L. Adopting Self-Medication Prevention Behaviors According to Health Belief Model Constructs. Hormozgan medical journal 2020, 24, e94791–e94791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanaeinasab, H.; Saffari, M.; Taghavi, H.; Karimi Zarchi, A.; Rahmati, F.; Al Zaben, F.; Koenig, H.G. An educational intervention using the health belief model for improvement of oral health behavior in grade-schoolers: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, N. Efficacy of Health Beliefs Model-Based Intervention in Changing Substance Use Beliefs among Mosul University Students: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Bionatura 2022, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, M.; Shamsi, M.; Khorsandi, M. Effect of Theory-Based Education on the Promotion of Preventive Behaviors of Accidents and Injuries among Mothers with Under-5-years-old Children. Iranian Journal of Health Education and Health Promotion 2016, 4, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ads, S.E.M.; Saied, H.; Melika, S.W. Mothers’ Perceived Risks and Practices for Over Counter Medications of Children Under Five Years. Tanta Scientific Nursing Journal 2023, 28, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucho Vásquez, K.C.; Loo Valverde, M.E.; Chanduvi Puicón, W.D. Self-medication in children with upper respiratory diseases in a mother-child center in Peru: Automedicación en niños con enfermedades de vías respiratorias altas en un centro materno infantil en Perú. Revista de la Facultad de Medicina Humana 2023, 23, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konk, M.C.; Yew, Y.P.; Chua, C.S.; Shalilan Dawie, D.D.; Lau, T.W.; Yun Kong, M.C. Practice and Perception of Self Medication in Children by Caregivers in Sibu Hospital. SARAWAK JOURNAL OF PHARMACY 2021, 7, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnpenny, A.; Beadle-Brown, J. Use of quality information in decision-making about health and social care services--a systematic review. Health Soc Care Community 2015, 23, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfe, A.; Cash-Gibson, L.; Car, J.; Sheikh, A.; McKinstry, B. Interventions for improving patients’ trust in doctors and groups of doctors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014, 2014, CD004134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejandro, A.L.; Bruce, M.; Leo, C. Parents’ awareness of antimicrobial resistance: a qualitative study utilising the Health Belief Model in Perth, Western Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health 2022, 46, 764–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsen, S.; Sajadi, M. The Effect of Education Based on Health Belief Model (HBM) in Mothers about Behavior of Prevention from Febrile Convulsion in Children. World Journal of Medical Sciences 2013, 9, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaboksavar, F.; Sharifirad, G.; Pirouzeh, R.; Jalilian, F.; Rafiei, N.; Mansourian, M. The child-to-family education program regarding self-medication: A theory-based interventional study. J Mother Child 2022, 26, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdea, V.; Tarciuc, P.; Ghionaru, R.; Pana, B.; Chirila, S.; Varga, A.; Mărginean, C.O.; Diaconescu, S.; Leibovitz, E. A Sensitive Public Health Issue—The Vaccine Acceptancy and the Anti-Pertussis Immune Status of Pregnant Women from a Romanian Metropolitan Area. Children 2023, 10, 640. [Google Scholar]

- Herdea, V.; Tarciuc, P.; Ghionaru, R.; Lupusoru, M.; Tataranu, E.; Chirila, S.; Rosu, O.; Marginean, C.O.; Leibovitz, E.; Diaconescu, S. Vaccine Hesitancy Phenomenon Evolution during Pregnancy over High-Risk Epidemiological Periods-"Repetitio Est Mater Studiorum". Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biezen, R.; Grando, D.; Mazza, D.; Brijnath, B. Dissonant views - GPs’ and parents’ perspectives on antibiotic prescribing for young children with respiratory tract infections. BMC Fam Pract 2019, 20, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bert, F.; Previti, C.; Calabrese, F.; Scaioli, G.; Siliquini, R. Antibiotics Self Medication among Children: A Systematic Review. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, W. Impact of the family doctor system on the continuity of care for diabetics in urban China: a difference-in-difference analysis. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e065612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Li, X.; Gao, J.; Liu, X.; Mao, Y.; Wang, R.; Zheng, P.; Xiao, Q.; Jia, Y.; Fu, H.; et al. Health Belief Model Perspective on the Control of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and the Promotion of Vaccination in China: Web-Based Cross-sectional Study. J Med Internet Res 2021, 23, e29329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heydaratabar, R.; Hatefnia, E.; Kazem Nezhad, A. The Knowledge and Factors Associated with Self-Medication Behavior of Mothers with Children Under Two Years Have Referred to Health Centers in City of Firuoz Kuh Based on the Health Belief Model. Alborz University Medical Journal 2016, 5, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccoby, N.; Farquhar, J.W.; Wood, P.D.; Alexander, J. Reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease: effects of a community-based campaign on knowledge and behavior. J Community Health 1977, 3, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Hoor, G.A.; Plasqui, G.; Ruiter, R.A.; Kremers, S.P.; Rutten, G.M.; Schols, A.M.; Kok, G. A new direction in psychology and health: Resistance exercise training for obese children and adolescents. Psychol Health 2016, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steering Committee for Human Rights in the fields of Biomedicine and Health (CDBIO). Guide to health literacy contributing to trust building and equitable access to healthcare. 2023, 65.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).