1. Introduction

Malnutrition is a medical condition caused by an imbalance between nutrient requirements and intake [

1]. The reported prevalence of malnutrition in hospitals varies from 28% to 73%, with older adults showing higher rates [

2]. In Spain, the prevalence of malnutrition in hospitalised patients ranges from 25% to 30%, increasing up to 40% in patients over 70 years of age [

1]. Malnutrition is a healthcare problem with serious consequences on clinical outcomes and patient’s health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [

2,

3] and entails a high use of healthcare resources and associated costs [

3,

4].

Enteral nutrition is indicated for patients with nutrition requirements who retain gastrointestinal function [

5]. In this context, home enteral nutrition (HEN) is recommended for those patients who do not require hospitalisation, as they can be in the social and familiar environment [

6], which has been shown to reduce infectious complications, number of hospital admissions, length of stay, and associated costs [

7,

8]. Not surprisingly, the prevalence of patients requiring HEN has increased worldwide in the last decades [

9]. In this regard, a European study from 2003 reported a prevalence ranging from 62 to 457 per million population per year [

10], while a recent Spanish study estimated a prevalence of 97.49 per million [

11]. .

The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) guidelines recommend measuring HRQoL periodically in patients receiving HEN to evaluate the impact and effect of the treatment [

5]. The importance of HRQoL assessment relies on its ability to provide information on different domains of patients’ lives and to facilitate shared decision-making, ultimately improving the quality of health care [

12]. Despite this and the fact that HRQoL evaluation is one of the established criteria in the Spanish National Health System Enteral Nutrition guideline to include patients in the HEN program [

13], registries carried out in Spain to date have not collected information on HRQoL using a specific questionnaire for patients with HEN [14-16]. HRQoL can be measured using specific questionnaires; however, there are limited specific questionnaires to measure HRQoL in patients with HEN [

17]. In this context, NutriQoL® (Societé des Produits Nestlé SA trademark), a specific questionnaire for assessing HRQoL in patients receiving HEN regardless of the underlying condition and the route of administration, was developed and validated in Spanish population, proving to be the one of the most appropriate tools available for this purpose [

12,

18,

19]. In fact, it has already been translated and adapted to French [

20] and Italian [

21] populations.

Despite guidelines recommendations and having a specific and validated tool, HRQoL is not often assessed in clinical practice. Therefore, there is scarce evidence on HRQoL evaluation in patients receiving HEN and their progression along the treatment duration that might help understand the impact of HEN on patients’ lives. Thus, in an effort to standardise and systematically collect data on the management and follow-up of patients receiving HEN, including data on HRQoL, our main goal was to record and describe the evolution of HRQoL in patients receiving HEN in routine clinical practice. Additionally, we aimed to describe patients’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics as well as their nutritional and disease status, and treatment adherence, determine the usefulness of HRQoL evaluation according to physicians’ perception, and provide evidence of the minimal clinically important difference in the NutriQoL® score.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was an observational, descriptive, prospective study carried out in ≥18 years old patients receiving HEN following routine clinical practice in two Spanish hospitals from November 2019 to July 2021. Patients were prospectively included in the study and followed-up during 12 months after inclusion (data cut-off in July 2022). Data were collected at the basal visit and after three, six and 12 months, as well as before HEN discontinuation if this happened before the final visit.

Adult patients who met the following criteria were included in the study: receiving HEN for less than a month before starting the study, being able to answer the NutriQoL® questionnaire (patients or caregivers), having an estimated survival over three months, and expectation of enteral nutrition lasting more than three months according to physicians’ criteria. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients. Patients who needed a translated version of the NutriQoL® and those who discontinued HEN before three months were excluded from the study.

2.2. Sample Size

Considering this is a pilot study, sample size was not estimated based on our main objective, but considering a sample size of 10% of the final study size or 10-40 participants [

22]. Nevertheless, sample size was estimated according to data from the Home and Ambulatory Artificial nutrition group and the Spanish Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (

Nutrición Artificial Domiciliaria y Ambulatoria de la Sociedad Española de Nutrición Parenteral y Enteral, NADYA-SENPE) registry of patients receiving HEN in Spain [

14,

15]; a minimum of eight patients per centre was estimated. According to the recruiting capacity of the participating centres, it was estimated that a total of approximately 30 patients could be recruited in each centre.

2.3. Study Variables

Sociodemographic (age, sex) and clinical variables (weight, body mass index, nutritional status according to the SGA and GLIM, degree of dependency according to Barthel, Charlson’s comorbidity index, HEN route of administration, patient’s HRQoL and nutritional treatment adherence) were collected from all patients. Physicians reported their perspective regarding patients’ health status, and the usefulness of HRQoL assessment.

2.4. HRQoL Assessment

HRQoL was assessed in each visit using the NutriQoL® questionnaire, which has been previously validated in Spanish population [

17]. Briefly, this questionnaire evaluates the impact of HEN on HRQoL, which is classified into five categories defined according to the score obtained: 1) very poor: 0-20 points; 2) poor: 21-39 points; 3) acceptable: 40-60 points; 4) good: 61-80 points; 5) excellent: 81-100 points.

To provide evidence of the minimal clinically important difference in the HRQoL total score in the NutriQoL® questionnaire that reflects a change in the patient's health status, patients with a positive or negative difference of ≥4 points in the questionnaire were selected and classified into two subgroups. For each subgroup, nutritional and health status evolution were described.

The usefulness of HRQoL evaluation for patient management was determined according to the physician’s perception, responding on a scale from 0 (not useful at all) to 10 (very useful) to the following question: How would you value the usefulness of HRQoL evaluation for patient management?

2.5. Nutritional Status Evolution

Patients receiving HEN were classified into three categories according to the subjective global assessment (SGA): 1) normal nutrition (category A); 2) risk or moderate malnutrition (B); 3) severe malnutrition (C). Furthermore, patients were classified into two categories according to malnutrition severity following the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM) criteria [

23]: 1) moderate malnutrition (grade 1); 2) severe malnutrition (grade 2).

2.6. Health Status Evolution

Physicians evaluated the patient’s health status on each visit responding on a scale from 0 (very bad) to 10 (very good) to the following question: How do you consider patients’ health status in relation to the underlying disease or main diagnose for which HEN is prescribed? Incidences or interventions due to changes in the patient's health status as well as actions taken by the physicians were described.

2.7. HEN Adherence

Patients were classified according to the categories in the HEN adherence questionnaire [

24] into low (0-2 points), moderate (3-4 points), or high (5-6 points) adherence.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Centrality and dispersion measures (mean, standard deviation [SD], minimum, P25, P50, P75, and maximum) were calculated for quantitative variables, while relative and absolute frequencies were obtained for the qualitative ones.

The analyses were performed in both the complete and the follow-up cohort using all valid data. Descriptive statistics were calculated according to valid data. Missing data were reported for each case and were not considered for the analyses. Data imputation techniques were not used for any of the variables.

Data were analysed using the statistical package STATA version 14 and the statistical significance was set at p-value < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

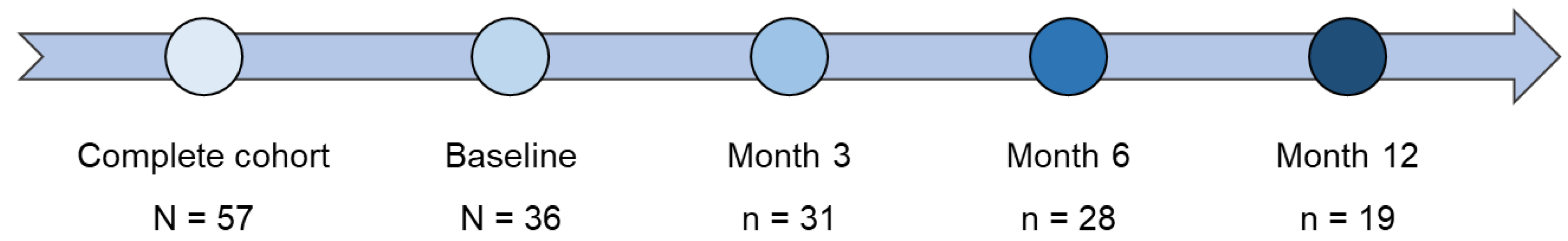

A total of 57 patients met the inclusion criteria and were included in the study (complete cohort). Of these, 36 patients were followed-up for at least three months after inclusion (follow-up cohort) (

Figure 1).

The mean age of these patients was 53.8 years, being 47.2% women. At baseline, 61.1% of the patients were at risk or with moderate malnutrition and 27.8% presented severe malnutrition according to the SGA. Additionally, 86.1% of the patients were malnourished according to GLIM criteria for malnutrition. More than half of the patients were oncologic patients (

Table 1). Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of all patients included in the study (both complete and follow-up cohorts) are shown in Supplementary

Table 1.

3.2. HEN Characteristics

At baseline, 16 (44.4%) and 10 (27.8%) patients in the follow-up cohort reported requiring HEN due to swallowing or transit mechanic alterations and clinical situations involving severe malnutrition, respectively (

Table 1).

Regarding the route of administration, 19 (52.8%) and 17 (47.2%) patients were fed orally and by tube or ostomy, respectively (

Table 1).

HEN characteristics for the complete cohort are shown in Supplementary

Table 1.

3.3. HRQoL Evaluation

Data on the evolution of the HRQoL during the study correspond to the 36 patients of the follow-up cohort. Most (84.4-90.3%) patients self-completed the NutriQoL®; only 9.7-15.6% were responded by their caregivers (

Table 2).

The mean (SD) NutriQoL® score obtained at baseline was 69.4 (12.6), which increased to 71.0 (14.6) and 74.3 (10.8) after three and 12 months of follow-up, respectively. These scores correspond to a good HRQoL according to the categories established by the NutriQoL® questionnaire. During the follow-up, 14 (38.9%) patients reported data in all visits. For these, the mean (SD) NutriQoL® score was similar to that obtained in the entire follow-up cohort (

Table 2).

Approximately 60% of the patients had a good HRQoL at baseline, while 25% had an excellent HRQoL. At the last follow-up visit (month 12), 57.9% of patients had a good HRQoL, while the percentage of patients with an excellent HRQoL increased to 31.6% (

Table 2). Details of the complete cohort can be found in Supplementary

Table 2.

According to the route of administration, patients who received oral HEN showed a higher NutriQoL® score compared with those fed by a non-oral method/route (

Table 2).

3.3.1 Minimal Clinically Important Difference

At the month 3 visit, 15 (48.4%) patients showed a clinically significant improvement in their HRQoL (≥4 points), while seven (22.6%) patients significantly worsened their HRQoL (≤ -4 points). After 12 months, nine (47.4%) of the 19 patients still receiving HEN showed a clinically significant improvement, while four (21.1%) showed an improvement between 0 and 4 points. Only three (15.8%) patients showed a significantly worse HRQoL (

Table 3).

3.3.2. Usefulness of HRQoL Evaluation

Physicians reported that HRQoL evaluation was useful for patient management, with a mean (SD) score at month 3 and month 6 visits of 7.10 (1.42) and 7.13 (0.99), respectively.

3.4. Nutritional Status

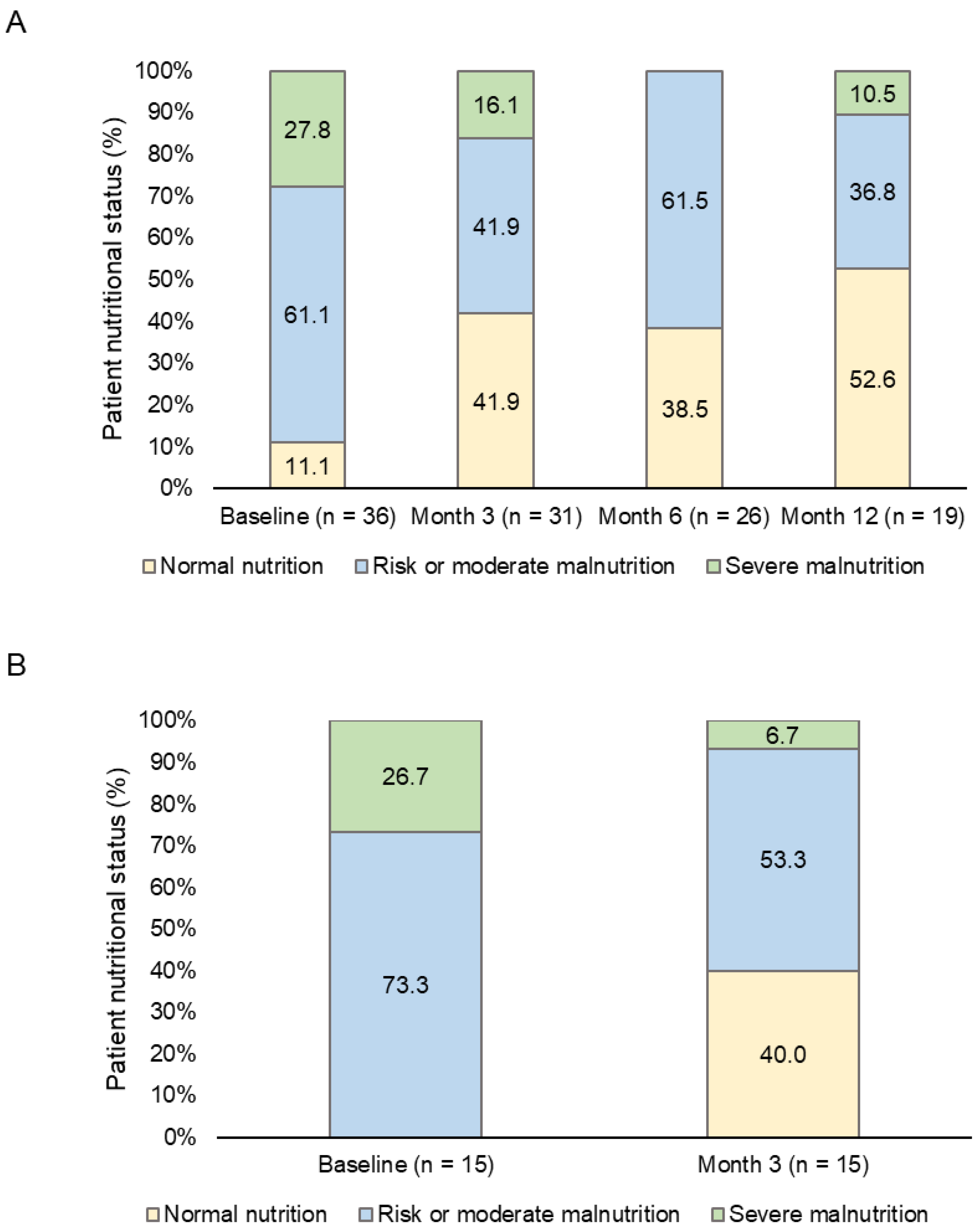

The analysis of patients’ nutritional status according to the SGA showed that 61.1% were at risk or with moderate malnutrition and 27.8% presented severe malnutrition at baseline. These values decreased to 36.8% and 10.5%, respectively, at month 12 (

Figure 2A). The differences between the basal and the subsequent visits were not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

In addition, the analysis of the 15 patients that significantly improved their HRQoL showed that all of them were, at least, at risk or suspicion of malnutrition. After three months, 40.0% of them showed normal nutrition and only 6.7% were severely malnourished (

Figure 2B).

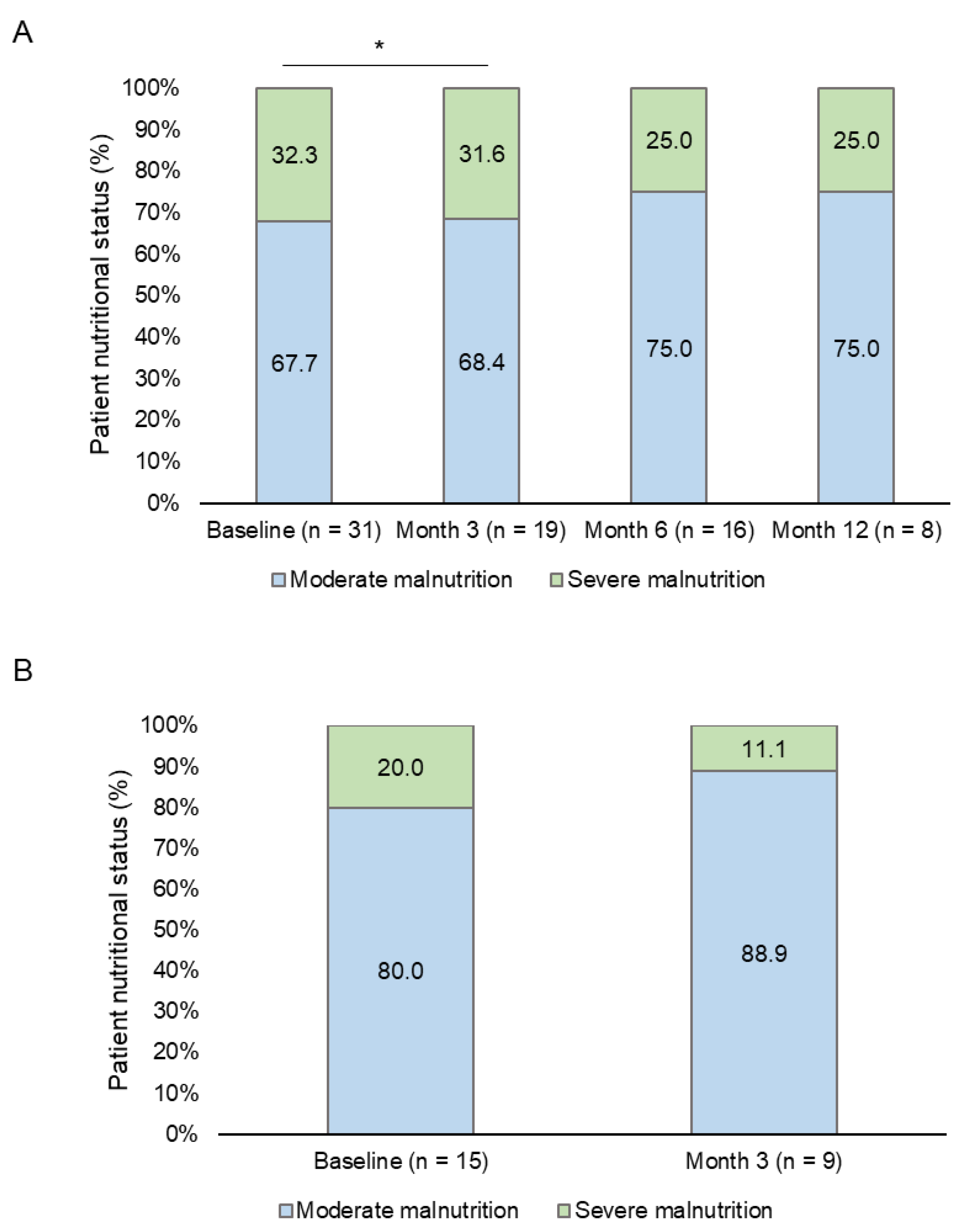

The nutritional evaluation following GLIM criteria showed that most (n = 31, 86.1%) patients were malnourished at baseline. Of these, 67.7% and 32.3% were classified with moderate and severe malnutrition, respectively. Eight patients met malnutrition criteria at the end of the follow-up period; 75% and 25% of them had moderate and severe malnutrition, respectively. However, only a statistically significant difference between the basal and the month 3 visits was found (p = 0.025) (

Figure 3A).

Most (80-88.9%) of the patients with clinically significant HRQoL improvement after three months of follow-up showed moderate malnutrition at both basal and month 3 visits (

Figure 3B). In addition, a reduction in the percentage of patients who met GLIM criteria for malnutrition was observed (

Table 4).

3.5. Health Status

Physicians scored the health status of the patients with a mean (SD) value of 6.53 (1.73) at baseline. This value, and consequently, patients’ health status, increased during the follow-up visits up to a mean (SD) score of 7.95 (1.72) at month 12.

3.6. HEN Adherence

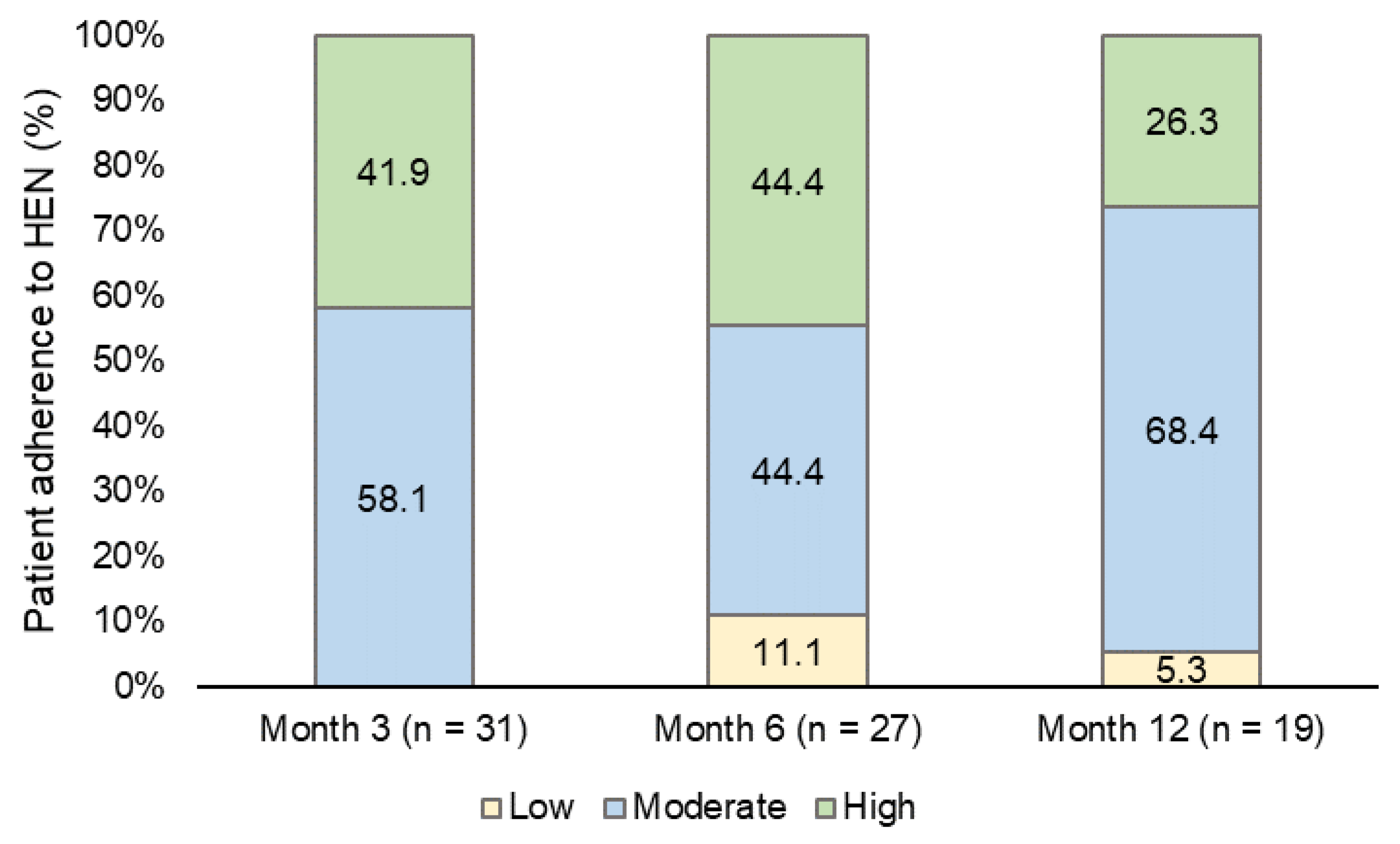

HEN adherence was moderate (58.1%) and high (41.9%) during the month 3 follow-up visit. The percentage of patients with moderate adherence increased to 68.4% at the last follow-up visit (month 12), while high adherence decreased to 26.3% (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

In our study, we describe and register the evolution of the HRQoL during 12 months in patients receiving HEN in Spanish routine clinical practice using a specific HRQoL questionnaire NutriQoL®.

Patients included in the study reported a NutriQol® score of 69.4 points at baseline, which increased to 74.3 points at the end of the follow-up period, showing a good HRQoL at both visits. In this sense, the percentage of patients with a good HRQoL slightly increased after 12 months.

At the month 3 follow-up visit, 15 patients showed a clinically significant improvement in their HRQoL. Their nutritional status improved at the first visit, with fewer patients reporting severe malnutrition according to both the SGA and GLIM criteria.

Patients’ NutriQoL® score increased over the follow-up period regardless of the route of administration, being patients receiving non-oral HEN the ones who showed a greater difference after 12 months of follow-up.

Data on the use of NutriQoL® are still scarce and limited to the Spanish population, but our results are in line with those previously published using this questionnaire; these showed that patients receiving HEN had a good HRQoL according to the NutriQol® score, which was higher in those receiving oral HEN compared with non-oral HEN [

17,

19]. Zamanillo et al. reported an increase in the NutriQoL® score after two months in patients with oral HEN but not in those with non-oral HEN [

19]. We observed the same trend after three months of follow-up. However, we observed an improvement in both subgroups after 12 months, showing that evaluating HRQoL for a longer period in patients receiving HEN is needed and should be included as an outcome variable in the studies. Overall, our results and those from previous studies show that NutriQoL® is valid and reliable tool to evaluate HRQoL, detecting variations in health status in patients receiving HEN regardless of their underlying condition, route of administration, and who responds to the questionnaire.

In the follow-up cohort, the nutritional status improved by the end of the follow-up period, reporting fewer patients at risk of malnutrition or severe malnutrition in favour of normal nutritional status. The observed improved nutritional status could be related to the high proportion of patients with at least moderate treatment adherence.

It is important to highlight that more than half of the patients in our cohort were oncologic patients. Previous studies in the field have reported that these patients can benefit from HEN following surgery. For example, Wu et al. showed that patients with oesophageal cancer receiving HEN improved their nutritional status and HRQoL after three months of HEN following esophagectomy [

25]. In this regard, two systematic reviews showed that HEN prevented weight loss in patients with gastric cancer after the surgery [

26,

27]. In addition, the results of their meta-analysis revealed that these patients improved their physical function and fatigue dimension but did not significantly improve their global HRQoL [

26,

27]. Noteworthy, the reviewed studies used different HRQoL questionnaires thus, standardising HRQoL assessment in clinical practice would be of help for results comparison and evaluation.

Finally, according to physicians’ evaluation, the evolution of patients’ health status related to the underlying disease for which HEN was prescribed was favourable. In addition, physicians considered it useful evaluating patients’ HRQoL for their management in routine clinical practice. This is of special interest as HRQoL improvement is probably related to the nutritional status evolution.

Our study presents strengths and limitations. The study has a prospective design and a long follow-up period. The use of the NutriQoL® questionnaire is recommended by the ESPEN guidelines [

5] as it allows to assess HRQoL reported by both patients and caregivers in patients with oral and tube HEN. On the other hand, the study was developed during the COVID-19 pandemic, which hindered the recruitment capacity of the centres. Moreover, not all patients could be followed-up for the entire duration of the study and we could not observe statistically significant differences in the nutritional status probably due to the sample size. However, the assessment of the clinical significance of NutriQoL® scores showed an improvement in patients’ HRQoL and nutritional and health status, although further studies will be needed to confirm these results. Furthermore, the evaluation of patients’ health status by the physicians could be considered subjective and therefore, using a validated tool for that purpose would be more suitable.

In conclusion, the results of our study show that implementing HEN in malnourished patients improves their nutritional and health status as well as their HRQoL. In addition, the assessment of HRQoL evolution using the NutriQoL® in patients receiving HEN is useful in routine clinical practice and should be considered for the nutritional evaluation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Table S1: Basal sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of each cohort.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.I-R, M.N.V.C, J.A-H., L.L., M.B.N. and M.L.B.; methodology, J.A.I-R, M.N.V.C, J.A-H., L.L. M.B.N. and M.L.B.; validation, L.L.; formal analysis, L.L.; investigation, J.A.I-R., M.N.V.C., E.J.L., P.Z.R., E.M.G.R., and G.C.C.; writing—review and editing, J.A.I-R, M.N.V.C, J.A-H., E.J.L., P.Z.R., E.M.G.R., G.C.C., L.L., M.B.N., and M.L.B.; supervision, J.A.I.R, M.N.V.C., and J.A-H.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and the APC were funded by Nestlé Health Science, Barcelona, Spain.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Bellvitge University Hospital (PR156/19).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Francisco Javier Pérez-Sádaba (at Outcomes ‘10) for project organization support and Víctor Latorre (at Outcomes ‘10) for medical writing support.

Conflicts of Interest

JA.I-R, MN.V.C., J.A-H., E.J.L., P.Z.R., EM.G.R., and G.C.C declare they have no conflicts of interests to disclose. M.B.N and M.L.B work at Nestlé Health Science. L.L. works for an independent research entity, Outcomes’10, that received funding from Nestlé Health Science to conduct the project and for medical writing.

References

- Álvarez-Hernández, J.; Planas Vila, M.; León-Sanz, M.; García de Lorenzo, A.; Celaya-Pérez, S.; García-Lorda, P.; Araujo, K.; Sarto Guerri, B. Prevalence and costs of malnutrition in hospitalized patients; the PREDyCES Study. Nutr Hosp 2012, 27, 1049-1059. [CrossRef]

- Pradelli, L.; Zaniolo, O.; Sanfilippo, A.; Lezo, A.; Riso, S.; Zanetti, M. Prevalence and economic cost of malnutrition in Italy: A systematic review and metanalysis from the Italian Society of Artificial Nutrition and Metabolism (SINPE). Nutrition 2023, 108, 111943. [CrossRef]

- Yárnoz-Esquíroz, P.; Lacasa, C.; Riestra, M.; Silva, C.; Frühbeck, G. Clinical and financial implications of hospital malnutrition in Spain. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2019, 27, 581-602. [CrossRef]

- Reber, E.; Norman, K.; Endrich, O.; Schuetz, P.; Frei, A.; Stanga, Z. Economic Challenges in Nutritional Management. J Clin Med 2019, 8. [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, S.C.; Austin, P.; Boeykens, K.; Chourdakis, M.; Cuerda, C.; Jonkers-Schuitema, C.; Lichota, M.; Nyulasi, I.; Schneider, S.M.; Stanga, Z.; et al. ESPEN practical guideline: Home enteral nutrition. Clin Nutr 2022, 41, 468-488. [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, C.; Mockler, D.; Lyons, L.; Loane, D.; Russell, E.; Bennett, A.E. A scoping review of best practices in home enteral tube feeding. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2022, 23, e43. [CrossRef]

- Apezetxea, A.; Carrillo, L.; Casanueva, F.; de la Cuerda, C.; Cuesta, F.; Irles, J.A.; Virgili, M.N.; Layola, M.; Lizán, L. Rasch analysis in the development of the NutriQoL® questionnaire, a specific health-related quality of life instrument for home enteral nutrition. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2017, 2, 25. [CrossRef]

- Klek, S.; Hermanowicz, A.; Dziwiszek, G.; Matysiak, K.; Szczepanek, K.; Szybinski, P.; Galas, A. Home enteral nutrition reduces complications, length of stay, and health care costs: results from a multicenter study. Am J Clin Nutr 2014, 100, 609-615. [CrossRef]

- Gramlich, L.; Hurt, R.T.; Jin, J.; Mundi, M.S. Home Enteral Nutrition: Towards a Standard of Care. Nutrients 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- Hebuterne, X.; Bozzetti, F.; Moreno Villares, J.M.; Pertkiewicz, M.; Shaffer, J.; Staun, M.; Thul, P.; Van Gossum, A. Home enteral nutrition in adults: a European multicentre survey. Clin Nutr 2003, 22, 261-266. [CrossRef]

- Campos Martín, C.; Luengo Pérez, L.M.; Álvarez Hernández, J.; Burgos Peláez, R.; Matia Martín, M.P.; Cuerda Compes, C.; C., N.R.; Martínez Olmos, M.A. Nutrición enteral en España durante 2022: registro NADYA-SENPE. Nutr Hosp 2023, 40, 17-145.

- Cuerda, M.C.; Apezetxea, A.; Carrillo, L.; Casanueva, F.; Cuesta, F.; Irles, J.A.; Virgili, M.N.; Layola, M.; Lizan, L. Development and validation of a specific questionnaire to assess health-related quality of life in patients with home enteral nutrition: NutriQoL(®) development. Patient Prefer Adherence 2016, 10, 2289-2296. [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. Guía de nutrición enteral domiciliaria en el Sistema Nacional de Salud; 2008.

- Wanden-Berghe, C.; Luengo, L.M.; Álvarez, J.; Burgos, R.; Cuerda, C.; Matía, P.; Gómez Candela, C.; Martínez Olmos, M.; Gonzalo, M.; Calleja, A.; et al. [Spanish home enteral nutrition registry of the year 2014 and 2015 from the NADYA-SENPE Group]. Nutr Hosp 2017, 34, 15-18. [CrossRef]

- Wanden-Berghe Lozano, C.; Campos, C.; Burgos Peláez, R.; Álvarez, J.; Frias Soriano, L.; Matia Martín, M.P.; Lobo-Támer, G.; de Luis Román, D.A.; Gonzalo Marín, M.; Gómez Candela, C.; et al. [Spanish home enteral nutrition registry of the year 2016 and 2017 from the NADYA-SENPE Group]. Nutr Hosp 2019, 36, 233-237. [CrossRef]

- Wanden-Berghe, C.; Campos Martín, C.; Álvarez Hernández, J.; Burgos Peláez, R.; Matía Martín, P.; de la Cuerda Compés, C.; Lobo, G.; Martínez Olmos, M.; De Luis Román, D.A.; Palma Milla, S.; et al. [The NADYA-SENPE Home Enteral Nutrition Registry in Spain: years 2018 and 2019]. Nutr Hosp 2022, 39, 223-229. [CrossRef]

- Apezetxea, A.; Carrillo, L.; Casanueva, F.; Cuerda, C.; Cuesta, F.; Irles, J.A.; Virgili, M.N.; Layola, M.; Lizán, L. The NutriQoL® questionnaire for assessing health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients with home enteral nutrition (HEN): validation and fi rst results. Nutr Hosp 2016, 33, 1260-1267. [CrossRef]

- Cuerda, M.C.; Apezetxea, A.; Carrillo, L.; Casanueva, F.; Cuesta, F.; Irles, J.A.; Virgili, M.N.; Layola, M.; Lizán, L. Reliability and Responsiveness of NutriQoL(®) Questionnaire. Adv Ther 2016, 33, 1728-1739. [CrossRef]

- Zamanillo Campos, R.; Colomar Ferrer, M.T.; Ruiz López, R.M.; Sanchís Cortés, M.P.; Urgelés Planella, J.R. Specific Quality of Life Assessment by the NutriQoL® Questionnaire Among Patients Receiving Home Enteral Nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2021, 45, 490-498. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.M.; Séguy, D.; Dive-Pouletty, C.; Papin, S.; Dainelli, L.; Layola, M.; Lizán, L. Linguistic and cultural adaptation of the NutriQoL ® questionnaire in France using ISPOR guidelines. In Proceedings of the 44th ESPEN Congress on Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism, Vienna 3-6 September, 2022.

- Cereda, E.; Bossi, P.; Borlotti, B.; Dainelli, L.; Layola, M.; Lizán, L. Linguistic and cultural adaptation of the NutriQoL® questionnaire in Italy. In Proceedings of the 44th ESPEN Congress on Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism, Vienna 3-6 September, 2022.

- Hertzog, M.A. Considerations in determining sample size for pilot studies. Res Nurs Health 2008, 31, 180-191. [CrossRef]

- Cederholm, T.; Jensen, G.L.; Correia, M.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Fukushima, R.; Higashiguchi, T.; Baptista, G.; Barazzoni, R.; Blaauw, R.; Coats, A.; et al. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition - A consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. Clin Nutr 2019, 38, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Wanden-Berghe , C.; Cheikh Moussa, K.; Sanz-Valero, J. Adherencia a la Nutrición Enteral Domiciliaria. Hospital a Domicilio 2018, 2, 11-18.

- Wu, Z.; Wu, M.; Wang, Q.; Zhan, T.; Wang, L.; Pan, S.; Chen, G. Home enteral nutrition after minimally invasive esophagectomy can improve quality of life and reduce the risk of malnutrition. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2018, 27, 129-136. [CrossRef]

- Xueting, H.; Li, L.; Meng, Y.; Yuqing, C.; Yutong, H.; Lihong, Q.; June, Z. Home enteral nutrition and oral nutritional supplements in postoperative patients with upper gastrointestinal malignancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr 2021, 40, 3082-3093. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Hu, L.W.; Qiang, Y.; Cong, Z.Z.; Zheng, C.; Gu, W.F.; Luo, C.; Xie, K.; Shen, Y. Home enteral nutrition for patients with esophageal cancer undergoing esophagectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 895422. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).