1. Introduction

Urban streams serve as essential natural resources for civilization, aiding in the supply of water, the prevention of flooding, the treatment of wastewater, and the control of illness. However, the surrounding terrain is altered physically and socially by urban development activities, such as traffic and infrastructural issues. As a result of mass tourism, global market liberalization, and decentralization, as well as climate change conditions, pressure has been placed on the development of historic regions. As one of these regions, historical urban landscapes have a pre-existing environment at their core, with both natural and physical aspects that contribute to defining the urban identity. Since they contain a variety of layers and different types of cultural assets, any rehabilitation effort must take national and international conservation principles into account. Besides, political influences, community values, and economic restrictions are accepted as the primary decision-making elements, to maintain physical integrity, stream ecosystems, and water quality when restoring urban streams [

1,

2].

The Deschambault Declaration (1982) mentions that making historic urban sites accessible and useful to the surrounding community contributes to the sustainable development of cultural heritage. In the following years, organizations like ICOMOS and ICCROM passed worldwide charters on the preservation and management of the natural and built landscapes within the historic city centers. The World Heritage Centre of UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) also set up a framework for the supervision of landscapes that reflect cultural diversity in the creation of historic urban identities [

3]. Recent discussions about cultural heritage have frequently emphasized ongoing community involvement as an essential element of identification and value-based preservation within historic urban settings.

Traditional human habitation includes a variety of architectural elements and their natural surroundings, as well as geographical areas where wildlife activity is visible in a variety of cultural and aesthetic contexts. The term "cultural landscape" is also used to describe a variety of human and environmental factors that illustrate the evolution of human civilization, its behavioral patterns, and settlements over time and space. Hence, cultural landscapes are essential since they include all of the architectural and cultural elements that have been created over time by numerous civilizations as a result of their continued use of the natural environment, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The regional variations in its definition are specifically studied [

4,

5,

6] to analyze the relationship with the global principles of the World Heritage Conventions ratified since the 2000s. Rössler and Chih-Hung Lin also use the terms "planned landscapes," "associative cultural landscapes," and "living or relict cultural landscapes" to describe its vast heritage, which is composed of both tangible and intangible elements [

7] (p.4). Meanwhile, scholars [

8,

9,

10] have extensively discussed its significance in the development of population dynamics and technological advancements. By concentrating on urgent global concerns including climate change, poor water quality, loss of biodiversity, and rising urbanization, the researchers [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15] also emphasize the significance of holistic and transdisciplinary approaches to its sustainability. Additionally, these researchers hoped to support the current scientific approaches to this subject by using place-based case studies to illustrate the conceptual framework for sustainability.

The Vienna Memorandum (2005) issued a ‘declaration on the protection of historic urban landscapes (HUL)’, investigating the guidelines to sustain the survival of cultural heritage in the face of rapid urbanization [

16]. Accordingly, the HUL strategy aims to help in identifying, managing, and safeguarding cultural landscapes within the context of contemporary cities by applying a range of traditional and cutting-edge strategies tailored to the social and cultural milieu. However, these urban development activities do not meet the requirements to ensure the continuity and authenticity of the cultural environment created and developed over time through the interaction of nature and architecture [

17]. In response to rising rent pressure in historic urban landscape areas, this would also help to produce development strategies that address the sustainability challenges of cultural heritage holistically. The relationship between memory and the authenticity of many cultures persists, although the physical form of legacy gradually changes through time. Understanding how much of a historic urban landscape may be conserved depends on how well continuity and change coexist along the natural heritage.

In light of this, authenticity is among the fundamental universal characteristics for the sustainability of the architectural and geographic identities of a developing city like Bursa, known as a World Heritage Site (UNESCO) located on the northwest side of Türkiye (

Figure 1a, 1b). As it has a multi-layered historic urban identity, the city contains listed archaeological remains, in addition to the buildings and sites, which comprise historical, architectural, and cultural assets to be conserved. Apart from the archaeological remains (from the Bithynians and Byzantines) and new industrial buildings of the Turkish Republican Period (since 1923), most of the existing historic buildings in Bursa date to the early and late periods of the Ottoman Empire [

Figure 1c].

This study focuses on the built and natural environment along Cilimboz Creek (

Figure 2), which is an antique watercourse flowing through the historic city center of Bursa, to reveal the challenges of preserving a traditional urban identity despite urban rehabilitation and transformation activities. Since this watercourse has been used for thousands of years for different purposes (e.g., domestic and industrial water use, recreational, and industrial discharges), its surrounding area consists of industrial buildings and multi-story apartment blocks in places. The northern part of the stream bed is within the borders of the Muradiye Neighborhood, which includes the traditional houses, mosques, and factory buildings from the Ottoman period. Thus, the historical urban landscape formed along the stream bed contains building groups that will define the cultural and sociological structure of the historical city center.

It is important to mention that numerous historic factories, houses, and mosques along the Cilimboz Creek have collapsed or been destroyed over time as a result of disasters, such as earthquakes and floods, together with misuse and neglect. However, there is currently no attempt to map and develop a comprehensive conservation plan for the study area, except for the studies [

18,

19,

20] describing documentation and restoration processes of the 19th-century silk factories that are considered a part of industrial heritage in Bursa. The literature is insufficient to explain the changes in the ecosystem within this Creek, whereas local newspapers have occasionally noted several infrastructure repairs and stream rehabilitation activities in its different segments. On the other hand, these initiatives have permanently altered the historic identity of this landscape due to the use of improper techniques and design models for also conservation of multi-layered architectural heritage in the study area.

Consequently, this historic urban landscape needs a unique perspective to assess how environmental policies and renovation initiatives have shaped the cultural landscape that surrounds Cilimboz Creek, a distinctive identity in this region of Bursa. This study aims to emphasize the importance of following a holistic approach to developing sustainable strategies while assessing the problems and threats continuously impacting the urban transformation in the study area. This assessment also helps to understand the historic and cultural values of this antique watercourse as a witness to the difficulties in changing its surrounding traditional urban identity, as well as explaining what needs to be done for the sustainability of this multi-layered landscape.

2. Materials and Method

There is a lack of information about the ecologic values/functions of Cilimboz Creek in the literature on the current and past conditions due to the changes caused by historic developments in Bursa. The information about the watercourse is limited to the historic writings [

21,

24,

27] about the water sources flowing through its historic city center. Moreover, the majority of analytical findings in the literature have focused on the pollution issues in the Nilüfer Stream [

29,

33,

34,

35], which is formed from several tributaries including Cilimboz Creek. In addition, there is not yet a holistic approach covered in scientific research examining the current state of this antique watercourse with its surrounding cultural heritage. Despite the historic and multi-cultural value of its surrounding historic built environment, which consists of historic Ottoman period houses and mosques to be preserved within the traditional urban texture of a neighborhood, only separate documentation works have been prepared for restoration proposals of historic industrial heritage along the Cilimboz Valley [

18,

19,

20].

This study aims to assess the competency and integrity of the implementations related to the sustainability of cultural and natural heritage forming the historic urban landscape along this antique watercourse. To evaluate its authenticity, the social and physical impacts on the transformation of this cultural landscape are also examined through the results of the urban development activities that have been implemented in the study area. By this method, it is possible to ascertain whether or not the urban traditional texture of the study area has been preserved. To conclude, the threats to the historic built environment in its Valley and possible solutions that prioritize the sustainability of a multi-layered landscape in the historic city core of Bursa are discussed. Shortly, the stages of the research method used in this study are listed as;

-

i.

Collection and classification of the archival documents for the literature review on the historical background of the study area,

-

ii.

Investigation of the current state of the defined built and natural environment along the 2.5 km section of Cilimboz Creek, starting from Pınarbaşı spring water (headwater) in the south to the Merinos Factory in the north, where it enters underground,

-

iii.

Evaluation of the effects of urban development activities, rehabilitation works, and restoration projects applied under the control of local and governmental institutions,

-

iv.

Discussion of threats in the sustainability of the cultural landscape identifying the study area, by comparing with similar implementations done in and abroad the country.

A combination of interpretive-historical and case-study research methods is used in this research, while multiple field studies were conducted along with the detailed data collection process. The field works were supported with low-altitude aerial images obtained from unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to identify various types of cultural assets that make up the physical framework of the historic urban landscape along Cilimboz Creek. Since one of the aims of this study is to identify the distinctive historical characteristics of the study area, the values, and potentials that make it essential to be preserved are given in detail. Initially, the natural and built structures within the study area are described as the values of this landscape in

Section 4.1, to reveal the variety of cultural properties forming its historic architectural and urban identity.

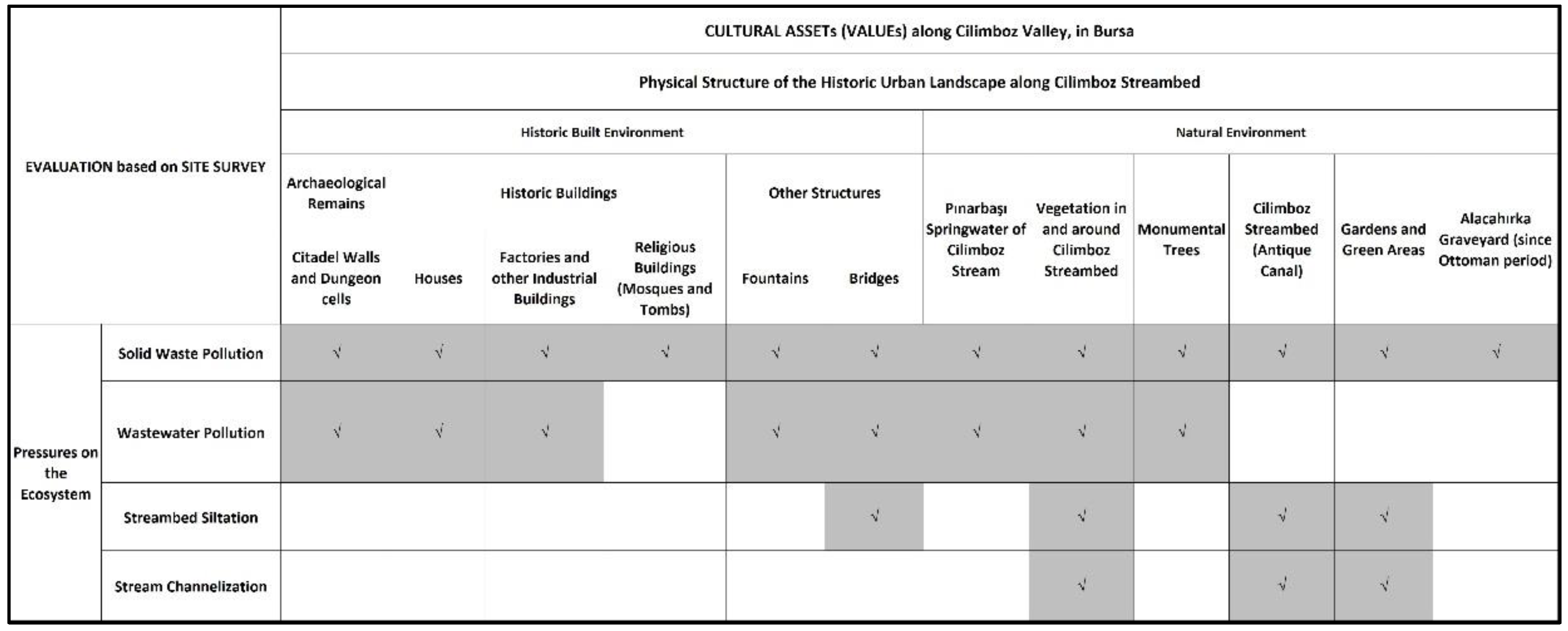

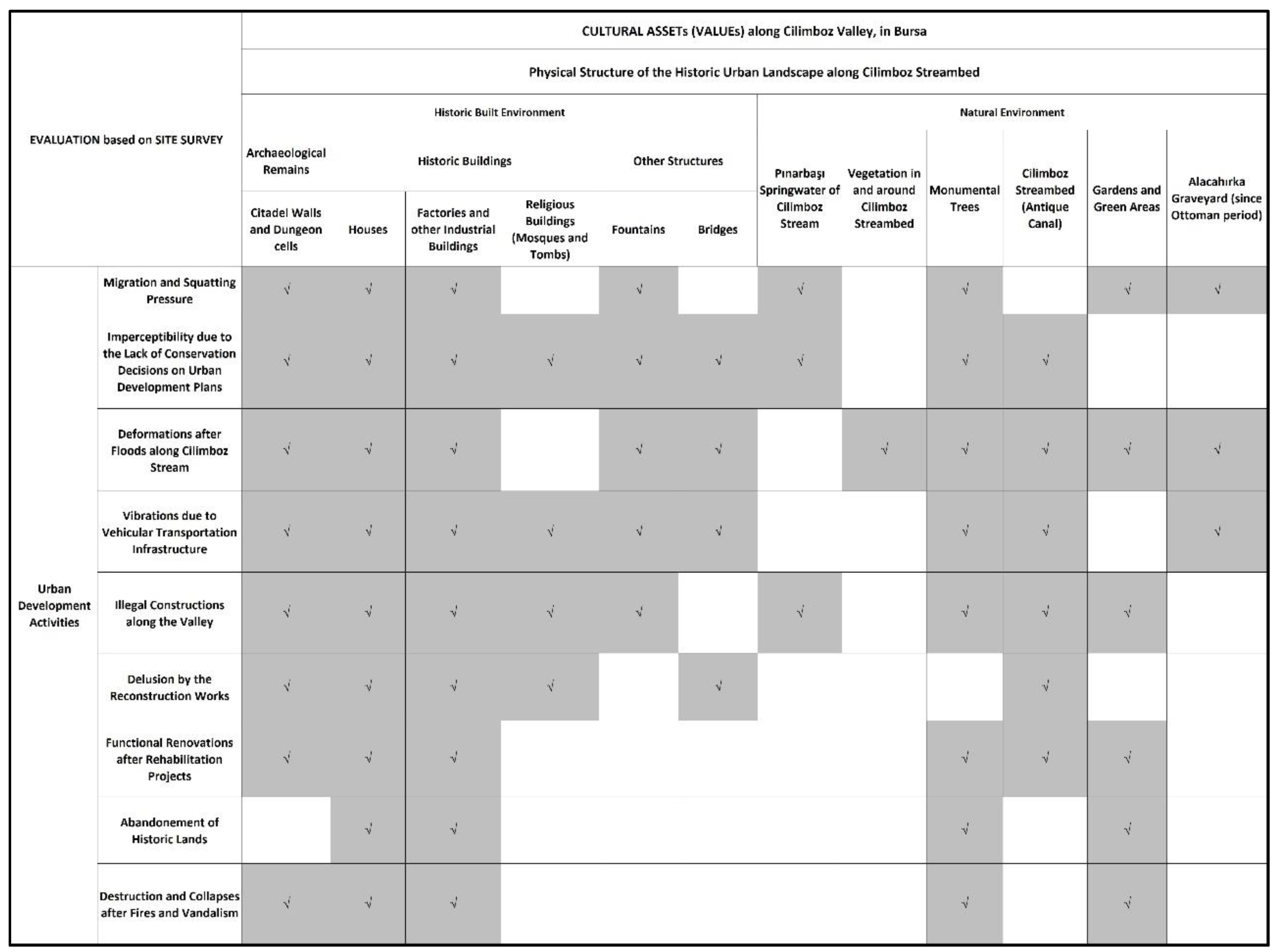

In this study, the information from the literature and the visual documents from the archives of governmental and local institutions in Bursa were obtained and consolidated to create a timeline for the urban history of this region. Both written and visual records were obtained as the primary sources by accessing the archives of the Bursa Regional Directorate of the State Hydraulic Works, Bursa Metropolitan Municipality, and Bursa Cultural Heritage Preservation Regional Board. Meanwhile, the matrix tables prepared to identify the main pressures on the historic built environment and the ecosystem in the Cilimboz Valley, which reveals the relationship between cultural assets (the values) and their conservation issues (the problems), each of which poses a threat to the sustainability of cultural heritage in Bursa (see

Section 4.2 and 4.3). The outcomes of the fieldwork were conducted in this study along with information obtained from the official reports and feedback from residents along the Cilimboz Creek. Additionally, decisions regarding the conservation status of the historic buildings and sites in the study area were evaluated within the framework of plans and projects, which were approved by the Regional Conservation Council of Bursa, to understand the conservation mobility in this part of the city core.

3. The Study Area: The Cilimboz Creek and its Historic Environs

The historic city core of Bursa is geographically divided into three sections by two urban streams, the

Nilüfer and

Gökdere, which results in the formation of fertile lands. The Nilüfer Stream, a vital water source for the agricultural fields at the north of the city, merges with a creek, named

Cilimboz (Phillippoz / Filiboz), on the outskirts of

Uludağ (Great Mountain) before emptying into the

Marmara Sea. Its stream bed is formed like a chest at the lowest point of this mountain’s outskirts, where the silhouette of the Citadel (

Hisar) may be seen from the southwest of the city (

Figure 3a–c).

Cilimboz, one of the creeks flowing through the historical city center, was transformed into an artificial canal along the western side of the castle walls during the Bythnian period, to serve as a ditch for the defense of the city and to control the flow of

Pınarbaşı natural spring water, which is known as the primary source of

Nilüfer stream. It was also used to supply clean water to the inhabitants until the late 19th century when sewage began to overflow from the old silk factories built alongside this streambed.

However, due to the ongoing multi-story constructions and infrastructure applications in this area, it is difficult to trace the streambed's original path. This plentiful and pure water source was used to irrigate crops, even though its mineral content, which contains lime, makes it difficult to drink. According to the literature, it also benefited several baths, factories, public fountains, as well as fountains at homes [

21]. It moved along the street between houses in the Citadel District. Through a conduit above the doorway, the spring water it carried flowed into the pool or well of the neighboring home's garden. The water left the inner garden and traveled through a pipe to another house, where it went under the door.

Two walls of a dungeon, rising on the incline of the travertine rocks at the east side of the streambed, have been uncovered in recent excavations (

Figure 4a and 4b). The tower's outer shell stones and the walls of the

Zindankapı (Dungeon Gate) section are reflected in the massive travertines that line the Cilimboz waterway. There is a tunnel-shaped cellar hidden within the Citadel's rocks, as reported by Yılmaz [

22]. The original width was 3.00 m, and the new height is 2.75 m; it is a brick-vaulted ceiling (

Figure 4c and 4d). For centuries, the public relied on this ancient tunnel for access to water and transportation of supplies. Travelers who visited Bursa in the 19th century noted that the valley was dotted with hermitages that had been founded in the late 7th century [

23,

24,

25]. In addition, the Ottomans took advantage of its water flow to power a 100-volt dynamo (coal-fired steam engine) that illuminated the city and ran several water mills. One of these mills was restored and reused as a restaurant, but the others have since collapsed and are no longer in existence. The Cilimboz Creek also had a significant impact on the growth of industrial infrastructure by providing the impetus for the construction of numerous factory buildings in the Muradiye District, located on the western side of the Valley. Moreover, several bridges, most notably the historic Cilimboz Bridge, have been built across this river to facilitate transportation and trade.

Europe's machine-made goods had already found a market in Bursa, by the middle of the 17th century. The historic trade center of the city underwent social, dynamic, and physical changes in response to the need for a new kind of industrial zone, after the Ottoman modernizing efforts of the 19th century. Meanwhile, the study area contained both commercial and residential buildings, as well as some industrial ones. The industries that grew included tanneries and silk mills were jointly established by Ottoman tradesmen and Levantine investors. Since the majority of factory workers were Armenians and Greeks, members of the minority groups tended to settle in these newly developed areas close to the factories. According to notes of the travelers, the Yahşibey and Miskinler Neighborhoods near the Cilimboz Creek were populated primarily by Greeks between the 16th and 18th centuries. In the northwest corner of the Citadel, there was also said to be the existence of a Jewish community, living between the historic trade center and the new manufacturing area along this Streambed. Consequently, the coexistence of various nations has enhanced the quality of the cultural heritage in this region.

The copious and quickly flowing water of the Cilimboz has also become a key consideration in the selection of a location for a silk mill. Taking advantage of the topography, the majority of the area's silk and leather production was concentrated on the western side of its stream bed (

Figure 5). Visitors in the 1860s reported seeing at least fifteen industrial buildings, mostly filatures, engaged in silk wrapping procedures to produce raw silk export material, most of which was shipped to France [

26] (p. 89, 96). The most famous industrial historical buildings in the region are the Fabrika-i Hümayun Factory, the Romangal Factory, the David Saban Brothers' Factory, the Savul Brothers' Factory, and the Ishak Iskender Factory [

18] (pp.39-41). The abundant and swiftly flowing water supply made hand-spinning silk impossible without steam-powered machinery, in this region. Hence, spinning mills required proximity to water because they used steam to generate power [

20]. The wastewater had to be removed right away from the manufacturing area after each cluster of cocoons was boiled, which makes this kind of waterway significant for the expansion of the sericulture industry in Bursa.

There is a gap in such kinds of regulations on stream rehabilitation from the 1930s till the 1990s. So much so that an action plan showing the boundaries of the historical city center of Bursa was prepared and approved in a conservation decision taken by the High Board of Real Estate, Antiquities and Monuments (GEEAYK) in 1979. In this plan, the boundaries of the historic urban areas to be protected are shown under the names of 'historical urban site,’ 'historical urban site protection zone,’ 'natural site protection zone,’ and 'natural site area'. Afterward, the initial conservation development plans for the Citadel (1985) and Muradiye (1991) Districts, which are also hosting the stream bed of the Cilimboz Creek, were prepared. Within the concept of these conservation plans, various types of projects were undertaken to address the natural and built-up environment along the Cilimboz Creek, at the beginning of the 20

th century (

Figure 6). Aiming to regulate the urban landscape along the Valley, these projects planned to reuse vacant spaces into public squares and natural leisure places. Three sub-project areas along the Cilimboz Creek were chosen as design zones. ‘The Muradiye Cultural Area Project’ was one of them, focusing on the organization and preservation of the open public spaces between the Alacahırka Quarter to the north and the Merinos Intersection to the south. It attempted to renovate and repurpose the industrial buildings next to the creek. To achieve cultural, touristic, and educational goals, the Romangal (Yılmazipek) Silk Factory and the Fabrika-i Hümayun Factory Complex buildings were also restored as part of this project. The Cilimboz Stream Landscape Design Project received top attention from the Regional Conservation Council and the Metropolitan Municipality of Bursa after the flood exploded in 2010. As a part of the rebuilding and rehabilitation of the area between Cilimboz Creek and

Fabrika-i Humayun, this project attempted to open the top of the streambed, which had been covered in concrete (Imperial Factory). ‘The Alacahırka Sports and Recreation Area Land Use Project’ ensured the preservation of the bridges, fountains, and trees in and around this streambed. Additionally, the central section of Bursa's local government, Osmangazi Municipality, mandated the development of plans for the rehabilitation of two canals that join the Cilimboz Creek.

4. Analysis and Results

The investigation on-site is crucial for evaluating the sustainability of a historic urban landscape. Within the aim of the study, the archaeological, natural, and architectural assets gathered in and around Cilimboz Streambed need to be discovered and presented as the components of cultural heritage in this land. By this, it is possible to recognize the values and potentials inherent in a sense of place, which has developed as a result of the linked efforts of nature and mankind over time. On the other hand, numerous harmful interventions have damaged the ecological and spatial structure distinguishing the study area, endangering the continuity of its surrounding cultural landscape. Hence, it is necessary to understand the primary factors causing changes in this historical urban landscape, which helps to find out problems and solutions through rehabilitation plans and restoration projects.

4.1. The Values of the Study Area

The value assessment in the study area is presented in

Table 1 the historic built environment, which is made up of industrial heritage building clusters and prehistoric structures that are still related to the archaeological ruins discovered along the Citadel walls at the south part of Cilimboz Valley. Because of its unique geographical, social, and architectural characteristics, which call for preservation, its surrounding traditional urban texture is valued as a composition of natural legacy and "cultural landscape." The greenery and large trees that grow in and near the streambed are also considered to be parts of the area's pristine natural environment, in addition to the

Pınarbaşı spring water source. The manmade green spaces, including playgrounds, cemeteries, and small agricultural areas in gardens, are recognized as modified recreation places that contribute to the green texture of the land. On the other hand, the historic built environment consists of archaeological remains along the Citadel walls, along with historic structures and street features that further contribute to identifying the traditional texture of its surrounding neighborhoods. In more detail, historic monumental structures are classified as factories and mosques, whilst historic houses are typically repaired to be reused as accommodations for touristic demands. For instance,

Fabrika-i Hümayun and

Romangal Silk Factories have been active for almost a century, between the end of the 19

th century and the 1990s, while the

Muradiye Complex, which is one of the world heritage sites in the city center of Bursa is still popular in religious tourism as having tombs of 12 dynasty member together with a mosque, madrasah, and imaret. Surrounding this Sultan Complex, the

Muradiye Neighborhood includes various types of cultural assets, composed of historic houses and mosques constructed in the Ottoman period, which reveals the historic identity of this urban landscape.

4.2. Changes in the Ecological Structure of the Study Area

The projects aimed at improving the region's infrastructure and ecological structure are based on westernization activities dating back to the late Ottoman Empire. Meanwhile, the Ottoman Bursa played a pioneering role in the application of urban development works, including the extension of its water and sewage networks.

Mahmut Celalettin Pasha, appointed Governor of Bursa in 1889, oversaw additional improvement projects, including the "drying, irrigation, flooding, protection, water supply, and energy generation" of urban streams in Bursa. In 1891, the Italian engineer Ravotti was hired to prevent flooding on the Bursa Plain and to drain the surrounding wetlands. Furthermore,

Rüştü Bey, Chief Engineer of Water Works, updated the concept in 1912 by proposing to build the

Sarıkaya Dam to monitor and control future

Nilüfer Stream floods [

20,

27]. In the years that followed, the Bursa Municipality established new agencies in charge of managing and improving the city's primary water resources, which flowed through the city. In 1917, the General Water Administration established a special commission to ensure that spring waters such as the

Pınarbaşı, Kavak, Akçalayan, and

Devrengeç were collected and transported to the city center. After the proclamation of the Turkish Republic in 1923, the authority on water resources was given to the Water Administration, which was established within the Bursa Municipality. An asphalt road covered a portion of the urban waterways, one of which is the

Cilimboz Creek, as a result of public improvements and infrastructural renovations done between the early 1930s and the late 1950s.

The problems and threats impacting the sustainability of the natural environment in the study area are given in

Table 2. Accordingly, the integrity of the ecosystem in and around the urban streams of Bursa is particularly in danger due to industrialization, which has led to unplanned urban development activities and a rapid increase in population. The recent academic and scientific studies on pollution in the streambeds emphasized that more sewage, fertilizer, and toxic metals have all contributed to a decline in water quality [

28,

29]. Regional and national economies have benefited from the increased interest in factories, but the ecological quality of these waterways has declined due to squatting and the rising demand for housing, which has resulted in the explosion of potentially hazardous structures and a mass exodus from rural areas [

30].

According to the archival documents gathered from DSİ (the State Hydraulic Works), the city's sewer system, which was once called the "black sewer" and had flat capstones on all four sides, was slowly changed by putting in pipes of different widths. That caused changes in the color and smell of the water in the Nilüfer stream so much that nothing could live in it. As one of the branches joining this major urban watercourse, the Cilimboz carried untreated wastewater from homes and factories and since the beginning of the 1980s, people living around the Cilimboz Valley have been complaining about the smell. Between 1982 and 1984, the Bank of Provinces (İller Bankası) prepared a study to see if it would be possible to build two wastewater treatment plants, one in the east and one in the west. In 1993, the sewage project was put into operation so that rainwater and wastewater were collected separately and rainwater was sent to the Nilüfer Stream.

Water and solid waste pollution, which was caused by a lack of infrastructure, were significant problems that threatened the integrity of the ecosystem in the study area (

Figure 7a). Meanwhile, the local government and other related institutions started covering streams by using asphalt to let vehicular traffic drive over, which has contributed to changing the ecosystem of the streambed in time. Moreover, the bottom of the Cilimboz Creek was covered with cement and stone masonry, which negatively affected the aquatic life that existed there before the restoration work (

Figure 7b and 7c). The lack of risk management strategies that should be mentioned in all related urban design, restoration, and rehabilitation projects for the conservation of this natural heritage against pollution and potential floods has also caused changes in the habitat of the area. Accordingly, the public's health might be at risk due to the frequent poor water quality caused by contaminant loading. To prevent or lessen coastal erosion, flooding, and increased pollution loads, it is obvious that Cilimboz Creek itself must first be monitored by qualified scientists and experts interested in stream rehabilitation.

4.3. Changes in the Spatial Structure of the Study Area

According to the information achieved by the fieldwork analysis, there was a labor shortage in the silk industries when ethnic minorities, including the Greek and Armenian populations, left Bursa as part of the "great population exchange". Meanwhile, internal migrations brought new laborers from rural areas to the old city core. The factory area established in the Cilimboz Valley was thought to be a source of income for new immigrants while remaining a significant source of funding for the nation. Beginning in the 1960s, this migration trend resulted in the creation of a new type of built environment, a kind of slum, in which homes were built quickly without the necessary permits. The first slums began to form toward the Uludağ (Great Mountain) slopes due to the low cost of the property and the difficulty in monitoring the enlarging in this area. The number of unauthorized structures in the Cilimboz Valley, which runs through the western Citadel and Muradiye Districts, increased seriously (

Figure 8). This ancient landscape area is thought to be incompatible with the new multi-story structures built across the streambed as a result of the massive urban transformation they caused.

The first expropriation works applied along the slopes of Cilimboz Creek were frequently mentioned in the local newspaper, Hakimiyet. According to the news article (dated April 4, 1959), Bursa Municipality decided to evacuate and demolish eight houses after inspecting the northern Cilimboz Valley to see if it was a landslide zone. Meanwhile, the municipality also considered the assessment of the local archaeologist committee, which noted that the ruins of the Citadel walls in this location may also pose a risk to the residents [

31]. In addition, the City Council had changed the zoning regulations to allow the construction of a nine-story parking lot at the northern end of the creek, in 1978. Following the flood and water pollution in this streambed, urban development activities were prepared under the pressure of housing and migration in the 1980s. All of these natural and man-made forces have caused consistent changes to the architectural character of this historic urban landscape. The stream rehabilitation and restoration projects were put in place to ensure stability and the authenticity of the cultural heritage in this study area. As one of them, the "Alacahırka Landscape Design Project" attempted to renovate a number of green spaces along this urban waterway for "playground areas" and "sportive amenities" (

Figure 9). However, the layout of such a recreation area, which is accessible to kids and teenagers, on this stream bed flooding occasionally, may be dangerous for people's safety.

After Cilimboz Creek was partially covered with asphalt for vehicular use, issues such as the structural stability of ancient buildings deteriorating occurred as a result of vehicle vibrations and pollution of the facades (

Figure 10). The negative effects of these urban development activities have long-term altered the authenticity of this historic urban area. As mentioned in the principles of the Muradiye Conservation Development Plan (1991), some historic structures, such as the Fabrika-i Hümayun (Imperial Factory), Yılmazipek, and the Duraner family's silk factory, were converted to be used in cultural facilities. The industrial heritage of this region has been further harmed by graffiti and other illegal implementations, but the majority of the historic manufacturing buildings along the Cilimboz Creek are still vacant. As a result, the functional renovations have changed both the spatial character of these abandoned historic structures and their surrounding landscape (

Figure 11). Due to the damages caused by the expropriations carried out by the Great Municipality of Bursa, most of the abandoned industry buildings and historic houses require immediate maintenance and consolidation. More importantly, houses built close to the stream bed are in great danger of collapsing or being destroyed, especially in the event of a flood or earthquake.

The primary restoration and repair work done after the numerous fires in these structures was inadequate scientifically, resulting in structural deformations and even collapses, significantly altering this historic neighborhood. Because conservation decisions were not made with a comprehensive perspective, integrity was lost, making it more difficult to identify the distinctive architectural features of the structures in the Cilimboz Valley (

Figure 12). The Conservation Development Plan prepared for the Muradiye District also notably lacked laws about Cilimboz Creek and its surrounding historic urban landscape. This plan was later updated in the 2000s, and the perimeter of its flood zone was expanded. As a result, the stream's service road was widened by five meters, allowing for the construction of new structures two meters above the highest watermark. The streambed, however, was not sufficiently cleaned up due to accumulated trash and overflowed. The buildings in the streambed collapsed as a result of the overflowing in Cilimboz Valley in October 2010, resulting in human casualties.

The municipality expropriated and destroyed the majority of the multi-story structures in the zoning parcels (a total of 45 parcels) along the streambed as part of a stream rehabilitation project (

Figure 13). Historic dwellings in the Alacahırka and Pınarbaşı Districts were to be demolished, and the Urban Design Project recommended that the houses within 7700 square meters of the stream be demolished. Unfortunately, neither information on how many of the destroyed structures were listed in the list nor any kind of paperwork regarding what had previously been done to the buildings was gathered. As these public improvement projects moved toward the north end of the Cilimboz Valley, the State Hydraulic Works (

DSİ) expanded and covered the streambed along the slope of the Citadel walls with concrete and stone. Natural riverbeds have been converted into constrained, narrow river corridors with tunnels made of concrete and other artificial materials, all of which are detrimental to the creek's ecology. As a result, the original boundaries of this ancient waterway are no longer discernible (

Figure 14).

In addition to these implementations, the southwest corner of the Citadel's walls between two gates,

Zindankapı and

Yerkapı were reconstructed by using modern building materials. Although the reconstruction approach is still open to discussion within the scope of national and international conservation projects, there is an extremely important problem in this practice. This practice of rebuilding without being supported by sufficient scientific evidence may also be a mistake for future generations, since it leads to the emergence of an almost completely imperceptible urban element that is quite different from the original, both in form and structure (

Figure 15). Even though the renovated remains of these gates serve as new landmarks in this historic urban region, recognizing the distinctive identity of the architecture along the

Cilimboz Creek has become dangerous. These erroneous and unconscious reconstructions now pose a risk to the sustainability and perceptibility of the multi-layered character of this cultural environment. Besides, inconsistencies between the old and modern structures applied in these reconstructions result in the creation of a ‘replica’ conflicting with ideas of authenticity and the essence of the location.

In brief, the changes in architectural and urban character of the study area have appeared due to both natural and manmade factors that caused permanent changes in the physical and social structure of the residential, industrial, and archaeological heritage forming the historic urban landscape along the Cilimboz Creek. Despite various types of restoration and rehabilitation works in both building and site scales, the damages related to the results of urbanization activities impact the transformation of the natural and built environment in the study area (

Table 3).

5. Discussion

Sustainable urban practices and conservation strategies are established in industrialized historic cities while taking into account the interaction between geographical and architectural heritage components. It is essential to conserve and sustain the historic urban landscape to promote awareness of the cultural identity defining the historic city core, which provides shifting from transformed to sustainable city centers. Assisting communities in their efforts to develop and adapt while preserving the values connected to their shared memories also supports the sustainability of a historic urban landscape (HUL). Accordingly, continuous development dynamics should facilitate urban growth while respecting the natural elements and their surrounding historic built environment. Thus, this research explains the transformation and conservation processes of a historic urban landscape along Cilimboz Creek, which witnesses the sustainability challenges in its surrounding traditional urban texture. By doing this, it is aimed to discover what must be done as a part of an urban development policy for Bursa, a World Heritage Site in Türkiye, to protect/preserve its cultural heritage.

This study also contributes to answering the question of what should be prioritized to raise

public awareness about the conservation of historic urban landscapes, which are accepted as a component of the multi-layered urban identity of the study area. By this, it would be possible

to increase the interest of relevant public and private institutions in the sustainability of the cultural landscape formed along the Cilimboz Valley. It would be useful to develop a Training Module [

36]

to assist lecturers in running three basic forms of knowledge transfer by providing public awareness exercises within

the concept of training programs in the rehabilitation of water and its environs. This module should be designed to develop the capabilities of governmental and local authorities about how to maintain a proper relationship between the proposed rehabilitation attempts and the national legal aspects concerning the continuity of the cultural landscape along Cilimboz Creek.

It is crucial to respect the values of the national and international communities while learning from local customs and perspectives because a comprehensive and integrated approach is required for the identification and conservation of a multi-layered structure within an overall sustainable development framework. Besides, examining the problems brought on by disputes between the law and regional organizations involved in stream rehabilitation initiatives is also a significant issue for the sustainability of the cultural landscape. As mentioned by the scholars [

1,

2] political influences, community values, and economic constraints are accepted as the basic decision-making factors in providing physical integrity, stream ecosystems, and water quality in urban stream rehabilitation. Exploring the issues arising from

conflicts between legislation and local institutions interested in stream rehabilitation projects is also essential.

Dynamic continuous development should promote urban expansion while honoring the surrounding historic built and natural environments. To conserve and perpetuate the unique traditional urban texture of the study area, any new rehabilitation initiatives should refocus the current planning efforts. Since this is just an assessment on the determination of the specific characteristic identifying the study area, the Cilimboz Valley, it is necessary to prepare a comprehensive site survey including a checklist of the aspects, such as the topography, surface drainage, circulation systems, land uses, man-made and natural water features, as well as a spatial organization that describes this historic urban landscape in detail. Accordingly, both habitable and non-habitable landscape structures should be considered together with manmade constructions, as well as their spatial character, form, and scale.

The creation of "cultural mapping" as a tool for defining

the "spirit of the place" is a great necessity for the sustainable development of historic cities [

2,

32]. Efforts to strike a balance between approaches to protecting and improving historic urban landscapes have drawn attention to

the concept of authenticity, which is deemed necessary for their sustainability. The intangible history of the area around Cilimboz Creek is essential to represent through the traditional construction techniques used in the silk industry of Bursa. Every component of this manufacturing culture, including the industrial history made up of old factories and the communities around them, needs to be preserved. The relationship between memory and originality of many cultures persists, although the physical form of legacy gradually changes through time. For the continuity in sense of this historic area, collaborative work should be organized by local authorities, universities, and private institutions, concerning the social and physical structure of the Cilimboz Valley, which is subjected to continuous and permanent changes in history.

The idea of integrity in applications done for the sustainability of a historic urban landscape is a critical criterion for cataloging, safeguarding, and regulating historical interactions in both tangible and intangible values. As having multi-layered traditional structure, the Cilimboz Valley, as the study area, is made up of geomorphology, hydrology, and natural features, as well as the historic and modern built environment. However, the plans and projects concerning the rehabilitation of its stream bed and its surrounding historic urban landscape have never been produced with a holistic approach (

Figure 4). Hence, there is still no particular sensitivity noted for the protection of its surrounding cultural landscape by using a holistic approach to find solutions to architectural and social issues as well as environmental ones.

6. Conclusion

Stream rehabilitation aims to solve the carrying capacity issue of an urban watercourse, together with initial settlement down by the channel applications. The monitoring of an urban stream is used to prevent or reduce bank erosion, flooding, and increased pollutant loads. Still, it may also be used for the protection of natural hydraulic conditions and urban aquatic habitats.

Within the Valley of Cilimboz Creek, the rehabilitation works have focused on shifting from natural streambeds to confined narrow corridors with channels canalized in concrete and other artificial materials forming both the bed and banks of the waterways. Besides, the pollutant loading also frequently leads to poor water quality, which threatens public health due to the increase in the bacteriological or chemical quality of urban streams. There are also illegal new buildings constructed along these three rivers’ streambeds since they have not been designated as natural sites, yet. Moreover, the new building constructions and new additions on the façade of traditional houses along Gökdere stream bed were not forbidden either. Hence, certain revisions, concerning new building constructions within the stream bed of Cilimboz, should be prepared in the planning decisions of the Muradiye Conseration Development Plan.

Consequently, an inconsistency is observed between the in situ conservation approach proposed for archaeological material and the conservation of overground cultural properties. Besides, the attitude of producing fake historic spaces, far from keeping the perceptional integrity and authenticity of the place, through demolishment and reconstruction of the traditional houses instead of conserving and reusing them with their original features and materials, was embraced, in addition to the inconsistencies between the old and new in the completion implementations.

References

- Findlay, S.J.; Taylor, M.P. Why rehabilitate urban river systems? Area 38.3 2006, 38/3, pp.312-325. [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, Patricia M. Urban Cultural Landscapes and the Spirit of Place. In: 16th ICOMOS General Assembly and International Symposium: ‘Finding the spirit of place – between the tangible and the intangible’, Quebec, Canada, 29 Sept – 4 Oct 2008.

- ICOMOS. UNESCO Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape (10 November 2011, Paris). Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/9-uncategorised/155-historic-urban-landscape (accessed on 11.8.2023).

- Fowler, P. World Heritage Cultural Landscapes, 1992–2002: A Review and Prospect. In Cultural landscapes: The Challenges of Conservation 2002.

- Akagawa, N; Sirisrisak, T. Cultural Landscapes in Asia and the Pacific: Implications of the World Heritage Convention. International Journal of Heritage Studies 2008, Volume 14, Issue 2, pp. 176-191. [CrossRef]

- Cocks, M.; Vetter, S.; Wiersum, K.F. From universal to local: perspectives on cultural landscape heritage in South Africa. International Journal of Heritage Studies 2018, 24:1, pp. 35-52. [CrossRef]

- Rössler, M.; Chih-Hung Lin, R. Cultural Landscape in World Heritage Conservation and Cultural Landscape Conservation Challenges in Asia. Built Heritage 2018-2, pp. 3-26. [CrossRef]

- Birks, H.H.; H.J.B. Birks, H.J.B.; Kaland, P.E., and Moe, D. The Cultural Landscape — Past, Present, and Future, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988.

- Jones, M. The Concept of Cultural Landscape: Discourse and Narratives. In Landscape Interfaces. Landscape series, volume 1, Palang, H. and Fry, G., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, 2003; pp. 21-51.

- Taylor, K.; Lennon, J. Cultural Landscapes: A bridge between culture and nature? International Journal of Heritage Studies 2011, 17:6, pp. 537-554.

- Steinitz, C. Toward a sustainable landscape with high visual preference and high ecological integrity: The loop road in Acadia National Park, USA. Landscape and Urban Planning 1990, 19/3, pp. 213-250. [CrossRef]

- Handley, J.; Pauleit, S.; Gill, S. Landscape, Sustainability, and the City, In Landscape and Sustainability, Taylor & Francis, 2007; pp. 183-211.

- Ahern, J. Urban Landscape Sustainability and Resilience: the Promise and Challenges of Integrating Ecology with Urban Planning and Design. Landscape Ecology 2013, 28, pp. 1203-1212. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.B; Wu, J.; Anderies, J.M. Sustainable Landscapes, and Landscape Sustainability: A Tale of Two Concepts. Landscape and Urban Planning 2019, 189, pp. 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnet, I.C.; Molnarova, K.J.; Brink, A.; Beilin, R.; Sklenicka, P. How Cultural Heritage Can Support Sustainable Landscape Development: The Case of Třeboň Basin. Landscape and Urban Planning 2022, vol. 226, pp.1-11.

- Van Oers, R. Towards New International Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Urban Landscapes (HUL). In Changing Role and Relevance of Urban Conservation Charters, Centro de Estudos Avancados da Conservacao Integrada Ceci, 2007; pp. 1-8.

- Nezhad, S.F.; Eshrati, P.; Eshrati, D. A Definition of Authenticity Concept in Conservation of Cultural Landscapes. ArchNet International Journal of Architectural Research (IJAR) 2015, Volume 9, Issue 1, pp. 93-107. [CrossRef]

- Oral, E.Ö.; Ahunbay, Z. Bursa’nın İpekçilikle İlgili Endüstri Mirasının Korunması [The conservation of the industrial heritage related to sericulture in Bursa]. İTÜ Dergisi / a, Mimarlık, Planlama, Tasarım, [İTÜ Journal / a, Architecture, Planning, Design] 2005, cilt: 4, sayı:2, pp: 37-46.

- Karadeniz, D. Endüstri Mirası Yapıların Korunması ve Kente Entegrasyonu: Bursa Örneği [Conservation and Urban Integration of Industrial Heritage Buildings: The Case of Bursa], unpublished master thesis, Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi, İzmir, 2020.

- Akkuş, M. Industrial Regions of Bursa According to the City’s Drainage Map of 1909, Uludağ Üniversitesi Fen-Edebiyat Fakültesi, Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi [Journal of Uludag University Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences] 2011/2, year:12, number: 21, pp. 147-155.

- Karataş, A.İ. Bursa Suları ve Su Vakıfları [Bursa Waterways and Water Foundations]. Uludağ Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi [Journal of Uludag University Faculty of Theology] 2008, 17/2, pp. 379-417.

- Yılmaz, İ. Şehir Sur Zindanları Kapsamında Bursa Zindanının Tespiti, Belgelenmesi ve Restitüsyonu [Identification, Documentation, and Restitution of Bursa Dungeon within the Scope of City Wall Dungeons]. Uludağ Üniversitesi Fen- Edebiyat Fakültesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi. [Journal of Uludağ University

Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences] 2016, 20/32, pp. 179-185.

- Baykara, T. Bursa’daki Cilimboz’un Bizans ve Selçuklu Şehirlerindeki Yeri [The Place of Cilimboz in Bursa in Byzantine and Seljuk Cities], In: 4. Uluslararası Bursa Tasavvuf Kültürü Sempozyumu [4th International Symposium of Bursa Sufi Culture], Bursa, 14-15 Ekim 2005.

- Uzer, İ. Bursa Suları [Bursa Waters]. Bursa Vilayet Matbaası, Halkevi Neşriyatı: 11, Bursa. 1941.

- Lowry, H. W. Seyyahların Gözüyle Bursa [Bursa through the Notes of the Travellers]. 1326-1923, çeviri: Serdar Alper, Eren Yayıncılık, İstanbul, 2004.

- Erder, L. Factory Districts in Bursa during the 1860s. METU Journal of the Faculty of Architecture (Spring 1975), Volume: 1, no: 1, pp. 85-99.

- Yalılı, M.; Akal Solmaz, S.K. Su Temini Tesislerinin Tarihsel Gelişimi Sürecinde Bursa İli [Bursa Province in the Process of Historical Development of Water Supply Facilities]. Uludağ Üniversitesi Mühendislik Mimarlık Fakültesi Dergisi [Journal of Uludag University Faculty of Engineering and Architecture] 2004, 9/1, pp. 171-181.

- Yalılı, M; Akal Solmaz, S. K.; Kestioğlu, K. Bursa Su Kaynakları Potansiyeli ve Kullanıcı Faktörü [Potential and User Factors of Water Sources in Bursa], Uludağ Üniversitesi Mühendislik Mimarlık Fakültesi Dergisi [Journal of Uludağ University Faculty of Engineering and Architecture] 2006, 11/2, pp. 1-13.

- Karaer, E.; Küçükballı, A. Monitoring of Water Quality and Assessment of Organic Pollution Load in the Nilüfer Stream, Turkey. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2006, 114, pp. 391–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalışkan, V.; Akbulak, C. Effects of Migrations to Bursa on the Process of Squatting: Squatter Houses on the Slopes of Uludağ. The Journal of International Social Research (Summer 2010), volume: 3, Issue: 12, pp. 115-122.

- Satış, İ. 1950-1990 Yılları Arasında Bursa’daki Mimarlık ve Planlama Faaliyetlerinin Yerel Basın Haberleri Üzerinden Değerlendirilmesi [Evaluation of Architecture and Planning Activities in Bursa, Between 1950-1990, Through Local Press News]. Unpublished. Master Thesis, Uludağ University, Bursa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dinçer, İ. Kentleri Dönüştürürken Korumayı ve Yenilemeyi Birlikte Düşünmek: Tarihi Kentsel Peyzaj Kavramının Sunduğu Olanaklar [Thinking Conservation and Renewal Together While Transforming Cities: The Possibilities of the Concept of Historic Urban Landscape]. ICONARP International Journal of Architecture and Planning 2013, Volume 1, Issue 1, pp. 22-40.

- Aşık, B. B. , and Özsoy, G., Determination of pollution status of Nilufer river by water and bottom sediment analysis. Water Supply, 2023, vol.23, no.1, pp. 343-355. [CrossRef]

- Dere, Ş. , Dalkiran, N. , Karacaoğlu, D. et al. Relationships Among Epipelic Diatom Taxa, Bacterial Abundances and Water Quality in a Highly Polluted Stream Catchment, Bursa – Turkey. Environmental Monitoring Assessment, 2006, 112, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorak, S. , and Çelik, H. Irrigation Water Quality of Nilüfer Stream and Effects of the Wastewater Discharges of the Treatment Plants. Ege Üniversitesi Ziraat Fakültesi Dergisi, 2017, 54 (3), pp. 249-257. [CrossRef]

- Maksimović, C. Urban Stream Rehabilitation - Lessons (to be) Learned from URBEM Project. Water Engineering Research, 2005, Vol. 6, No. 4, pp. 189-195.

- URL-1. https://tr.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dosya:Bursa_in_Turkey.svg (last accessed 03.09.2023).

- URL-2. https://alanbaskanligi.bursa.bel.tr/berat/ (last accessed 03.09.2023).

- URL-3. https://tr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Osmangazi (last accessed 01.09.2023).

- URL-4. https://fotograf.bursa.com.tr/cilimboz-deresi/cilimboz-deresi-hava-nisan-2013-2/ (last accessed 01.09.2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions, and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Figure 1.

(a) Geographical Map of Bursa (URL-1), (b) Membership Document of Bursa as the UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Turkey (URL-2), (c) Current view of Bursa (URL-3).

Figure 1.

(a) Geographical Map of Bursa (URL-1), (b) Membership Document of Bursa as the UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Turkey (URL-2), (c) Current view of Bursa (URL-3).

Figure 2.

Cilimboz Creek from different views (URL-4).

Figure 2.

Cilimboz Creek from different views (URL-4).

Figure 3.

(a) The locations of the urban streams flowing through the historic city center of Bursa (source: the historic map dated 1905, from the archive of Bursa Metropolitan Municipality), (b) Location of the Pınarbaşı spring water at the southern end of the Cilimboz Creek (the aerial photo from Archive of Bursa Metropolitan Municipality, 2021) (c) Views of the Cilimboz stream bed (photographed by the Author, 2022).

Figure 3.

(a) The locations of the urban streams flowing through the historic city center of Bursa (source: the historic map dated 1905, from the archive of Bursa Metropolitan Municipality), (b) Location of the Pınarbaşı spring water at the southern end of the Cilimboz Creek (the aerial photo from Archive of Bursa Metropolitan Municipality, 2021) (c) Views of the Cilimboz stream bed (photographed by the Author, 2022).

Figure 4.

Before (a) and after (b) the excavations around the Zindankapı region, (c) The documentary plan drawing, and (d) the photograph of the tunnel. (Sources: (a) from the archive of Bursa Metropolitan Municipality, (b)photographed by the Author, 2023, (c) and (d): Yılmaz, “Şehir Sur Zindanları”, 179, 185.).

Figure 4.

Before (a) and after (b) the excavations around the Zindankapı region, (c) The documentary plan drawing, and (d) the photograph of the tunnel. (Sources: (a) from the archive of Bursa Metropolitan Municipality, (b)photographed by the Author, 2023, (c) and (d): Yılmaz, “Şehir Sur Zindanları”, 179, 185.).

Figure 5.

Historic (a) and current (b) views of the industrial area within the Cilimboz Valley. (c) The location of silk factories on the current map of Bursa (2021) (source: photographs and maps were taken from the archive of Bursa Metropolitan Municipality).

Figure 5.

Historic (a) and current (b) views of the industrial area within the Cilimboz Valley. (c) The location of silk factories on the current map of Bursa (2021) (source: photographs and maps were taken from the archive of Bursa Metropolitan Municipality).

Figure 6.

The sub-project areas of the Cilimboz Stream rehabilitation project (source: archival of Bursa Municipality).

Figure 6.

The sub-project areas of the Cilimboz Stream rehabilitation project (source: archival of Bursa Municipality).

Figure 7.

(a) Solid waste and water pollution within the Cilimboz Stream bed, (b) Covering the stream bed with asphalt for vehicle transportation, (c) Ground covering within the streambed with reinforced concrete and stone masonry (sources of historic photographs: archives of the State Hydraulic Works (DSİ), Bursa City Museum, and the currently photographed by the Author, 2022).

Figure 7.

(a) Solid waste and water pollution within the Cilimboz Stream bed, (b) Covering the stream bed with asphalt for vehicle transportation, (c) Ground covering within the streambed with reinforced concrete and stone masonry (sources of historic photographs: archives of the State Hydraulic Works (DSİ), Bursa City Museum, and the currently photographed by the Author, 2022).

Figure 8.

Views of buildings constructed in the Cilimboz Valley; most of these buildings were constructed illegally when new immigrants from rural areas came to the city (the Author, 2022).

Figure 8.

Views of buildings constructed in the Cilimboz Valley; most of these buildings were constructed illegally when new immigrants from rural areas came to the city (the Author, 2022).

Figure 9.

Urban design projects along the Cilimboz Stream bed; Alacahırka Sports and Recreation Area, Children Playground Design (the Author, 2022) .

Figure 9.

Urban design projects along the Cilimboz Stream bed; Alacahırka Sports and Recreation Area, Children Playground Design (the Author, 2022) .

Figure 10.

Facade deterioration on historic dwellings and structural cracks on the travertine cliffs, both caused by construction on the slopes of the Citadel walls (the Author, 2022).

Figure 10.

Facade deterioration on historic dwellings and structural cracks on the travertine cliffs, both caused by construction on the slopes of the Citadel walls (the Author, 2022).

Figure 11.

Damaged and vandalized buildings (the Author, 2023).

Figure 11.

Damaged and vandalized buildings (the Author, 2023).

Figure 12.

Photographs showing the decrease of clear historical views within the Cilimboz Valley (the Author: 2021).

Figure 12.

Photographs showing the decrease of clear historical views within the Cilimboz Valley (the Author: 2021).

Figure 13.

(a) Before and after a flood along the southern part of the Cilimboz Creek, (b) The process of rehabilitation, expropriation, and demolishment of the buildings constructed along the Cilimboz Valley. (sources: the archive of Bursa Municipality).

Figure 13.

(a) Before and after a flood along the southern part of the Cilimboz Creek, (b) The process of rehabilitation, expropriation, and demolishment of the buildings constructed along the Cilimboz Valley. (sources: the archive of Bursa Municipality).

Figure 14.

The process of rehabilitation; concrete covering the bottom of the Cilimboz Creek (source: the archive of DSİ (the State Hydraulic Works)).

Figure 14.

The process of rehabilitation; concrete covering the bottom of the Cilimboz Creek (source: the archive of DSİ (the State Hydraulic Works)).

Figure 15.

The reconstruction process of the historic Citadel walls (sources: archive of Bursa Metropolitan Municipality (2021) and the Author, 2022).

Figure 15.

The reconstruction process of the historic Citadel walls (sources: archive of Bursa Metropolitan Municipality (2021) and the Author, 2022).

Table 1.

Cultural Assets (VALUEs) along the Cilimboz Creek.

Table 1.

Cultural Assets (VALUEs) along the Cilimboz Creek.

Table 2.

Relation between Pressures on the Ecosystem and The Cultural Assets along the Cilimboz Valley.

Table 2.

Relation between Pressures on the Ecosystem and The Cultural Assets along the Cilimboz Valley.

Table 3.

Relation between Urban Development Activities and Cultural Assets along the Cilimboz Valley.

Table 3.

Relation between Urban Development Activities and Cultural Assets along the Cilimboz Valley.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).